Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

This extensive research report provides a rigorous, expert-level comparative analysis of Islam and Sikhism, two of the world’s major monotheistic traditions. While originating in distinct geopolitical and temporal spheres—Islam in 7th-century Arabia and Sikhism in 15th-century Punjab—the two faiths exhibit profound theological resonances that transcend their Semitic and Indic classifications. This document explores the core metaphysical convergences between the Islamic concept of Tawhid (Absolute Oneness) and the Sikh doctrine of Ik Onkar (One Supreme Reality), while critically examining their soteriological divergences regarding the afterlife (Resurrection vs. Reincarnation) and cosmic law (Judgment vs. Karma).

Leveraging a vast array of scholarly sources and specific insights from The Muslim Times, the report dissects shared ethical imperatives, including the rejection of idolatry (Shirk), the prohibition of priesthood, and the concept of righteous warfare (Jihad and Dharam Yudh). Furthermore, it investigates the unique intertextual relationship between the two faiths, exemplified by the inclusion of the Muslim Sufi mystic Baba Farid’s verses within the Sikh canon, the Guru Granth Sahib. The analysis extends to social praxis, comparing the redistributive economics of Zakat and Vand Chakko, the dietary laws of Halal and Jhatka, and the distinct approaches to gender and social stratification. By synthesizing historical narratives with deep theological exegesis, this report illuminates how Sikhism and Islam, while maintaining distinct spiritual identities, share a “genetic” vocabulary of devotion to the Formless One, offering a nuanced framework for understanding their historical intersections and contemporary relevance.

1. Historical and Geopolitical Genesis: The Desert and the Five Rivers

To understand the intricate relationship between Islam and Sikhism, one must first map the distinct topographies—both physical and spiritual—from which they emerged. The theological architecture of a faith is often inextricably linked to the socio-political challenges of its genesis.

1.1 The Arabian Context and the Rise of Islam

Islam arose in the early 7th century CE in the Arabian Peninsula, a landscape dominated by tribal factionalism and polytheistic idolatry. The Prophet Muhammad’s mission was fundamentally a corrective one: to restore the primordial monotheism of Abraham (Millat Ibrahim) which had been corrupted by the introduction of idols into the Kaaba.1 The revelation of the Quran occurred in a linear historical context, emphasizing a definitive break from the “Age of Ignorance” (Jahiliyyah). The socio-political exigency was the unification of warring tribes under a single divine law (Sharia) and a single sovereign deity (Allah). Thus, Islam codified a legalistic and social framework early in its development, merging spiritual authority with political governance.2

1.2 The Punjabi Milieu and the Advent of Sikhism

Sikhism emerged nearly nine centuries later, in the fertile plains of the Punjab (land of “Five Waters”) in the Indian Subcontinent. By 1469, the year of Guru Nanak’s birth, Islam was not a distant rumor but the religion of the ruling elite—the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughals. Punjab was the gateway for Islamic invasions into India, making it a crucible of intense cultural and religious churning.2

The spiritual landscape of 15th-century North India was characterized by a ossified Hinduism, burdened by the caste system and ritual formalism, and an Islam that was politically dominant but internally diverse, ranging from the orthodox Ulama to the ecstatic Sufis. The Bhakti movement (devotional Hinduism) and Sufism (mystical Islam) were already eroding the rigid boundaries between the two faiths. Guru Nanak’s emergence was not merely a syncretic blending of these two, but a revelation of a “third path” that claimed to transcend religious labels entirely. His famous declaration after his mystical immersion in the River Bein—”There is no Hindu, there is no Musalman”—was a metaphysical assertion that the labels used to categorize humanity were socially constructed and spiritually irrelevant in the eyes of the One Reality.1

1.3 The Intersection of Semitic and Indic Thought

Scholars have long debated whether Sikhism is an offshoot of the Bhakti movement or a distinct revelation influenced by Islamic monotheism. The consensus in modern scholarship, supported by the research snippets, is that while Sikhism utilizes the vocabulary of its time (borrowing from both Sanskrit and Persian/Arabic traditions), it possesses a unique theological identity.4 However, the influence of Islam is undeniable. The Guru Granth Sahib is replete with Islamic terminology—words like Hukam (Command), Raza (Will), Nadar (Grace), Khasam (Master), and Parvardigar (Nourisher) appear frequently, indicating that the Sikh Gurus were deeply conversant with Islamic theology and sought to redefine these concepts within their own spiritual framework.5

2. Metaphysics of the Divine: Tawhid and Ik Onkar

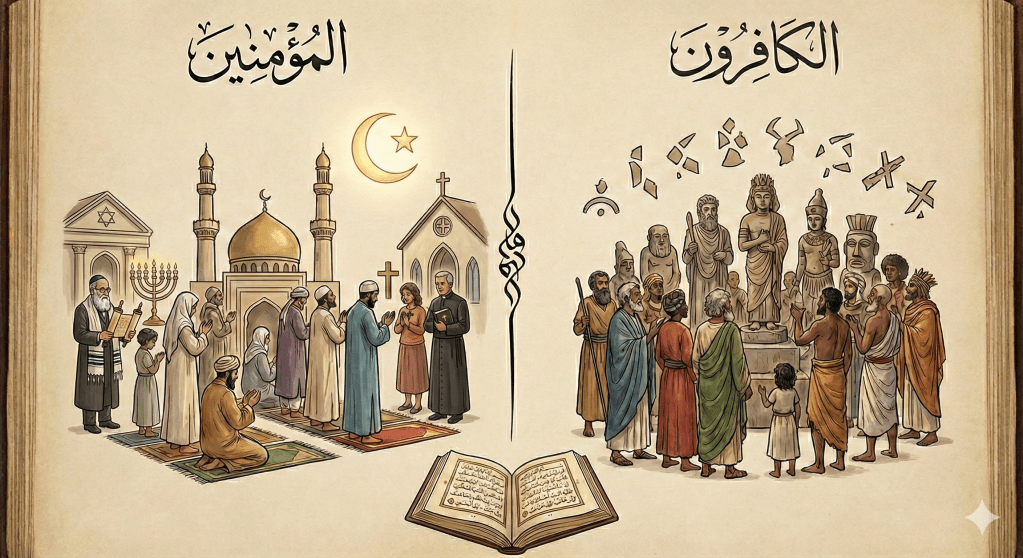

The most striking similarity between Islam and Sikhism is their uncompromising monotheism. Both faiths were born as iconoclastic responses to the perceived polytheism or idolatry of their surroundings. Yet, beneath the shared banner of “Oneness,” subtle philosophical distinctions exist regarding the relationship between the Creator and the Creation.

2.1 Tawhid: The Transcendent Oneness

In Islam, the concept of God is encapsulated in Tawhid, which asserts the absolute, indivisible oneness of Allah.

- Absolute Transcendence: The Quranic Surah Al-Ikhlas (Chapter 112) serves as the definitive creed: “Say: He is Allah, the One and Only; Allah, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him”.2 This definition emphasizes God’s distinctness from creation. Allah is the Creator, Sustainer, and Judge, but He is not the creation itself. To associate any partner or form with Allah is Shirk, the only unforgivable sin in Islamic theology.7

- Attributes: Allah is described through His 99 Names (Asma ul-Husna), such as Ar-Rahman (The Merciful), Al-Haqq (The Truth), and Al-Qahhar (The Subduer). While Islam acknowledges God’s nearness (“closer than the jugular vein”), orthodox theology generally maintains a creator-creation duality to preserve the sanctity of the Divine.3

2.2 Ik Onkar: The Immanent Oneness

Sikhism commences with the Mool Mantar, the foundational creed which defines the nature of the Divine as Ik Onkar.

- One Universal Reality: Ik (One) Onkar (Creator/Sustainer/Destroyer) signifies that there is only One Reality that permeates everything. Unlike the dualistic tendency in some interpretations of Tawhid, Ik Onkar implies a non-dualistic monotheism, or Panentheism.8

- The Attributes of Waheguru: The Mool Mantar describes God as Sat Nam (True Name), Karta Purakh (Creative Being Personified), Nirbhau (Without Fear), Nirvair (Without Hate), Akal Moorat (Timeless Form), Ajuni (Unborn), Saibhang (Self-Existent).1

- Rejection of Incarnation: Like Islam, Sikhism vehemently rejects Avtarwaad (the Hindu concept of divine incarnation). God does not enter the womb (Ajuni). The Guru Granth Sahib states, “May that mouth be burnt which says that the Lord takes birth.” This aligns perfectly with the Islamic rejection of God begetting or being begotten.7

2.3 Panentheism vs. Monotheism: A Philosophical Divergence?

A critical insight from the research suggests that while both are “monotheistic,” the texture of that monotheism differs.

- Islam generally adheres to Classical Theism: God is separate from the world.

- Sikhism leans towards Panentheism: God is in the world, yet distinct from it. “You have thousands of eyes, and yet You have no eye; You have thousands of forms, and yet You have not one form” (Guru Granth Sahib, Ang 13).8

- Synthesis: However, this divergence narrows when considering the Islamic Sufi tradition. The concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Being), championed by Ibn Arabi, posits that “there is no true existence except Allah,” and the world is merely a reflection of His names.9 This Sufi interpretation is strikingly similar to the Sikh view that the world is the “Body of the Lord.” The research indicates that Guru Nanak’s dialogues with Sufis likely utilized this shared metaphysical grammar.10

2.4 Comparative Theological Attributes

| Attribute | Islam (Tawhid) | Sikhism (Ik Onkar) |

| Unity | Absolute Indivisibility (Ahad) | One Supreme Reality (Ik) |

| Form | Formless (Bila Kayf); No image | Formless (Nirankar); No idol |

| Creation | Distinct from Creator (Creator vs. Created) | Permeated by Creator (Oat Pot – Warp and Woof) |

| Incarnation | Rejected (Jesus is a Prophet, not God) | Rejected (Rama/Krishna are Avatars, not God) |

| Gender | Beyond Gender (referenced as ‘He’ linguistically) | Beyond Gender (referenced as Father, Mother, Husband) |

| Visuals | Calligraphy allowed; Statues forbidden | Calligraphy allowed; Idols forbidden |

3. The Mystic Bridge: Sufism and the Sikh Gurus

The relationship between Islam and Sikhism is not merely adversarial or comparative; it is deeply intertextual. The presence of Muslim voice within the Sikh scripture is a unique phenomenon in the history of world religions.

3.1 Baba Farid: The Muslim Voice in the Guru Granth Sahib

The most potent symbol of this spiritual kinship is Sheikh Farid-ud-din Ganj-i-Shakar (Baba Farid), a 12th-century Chishti Sufi saint. His verses (Sloks) are incorporated into the Guru Granth Sahib alongside the writings of the Sikh Gurus. This was not a token gesture of inclusion; it was a theological affirmation that the “Word of God” (Shabad) is not confined to a single community.12

- The Theological Implications: By including Farid’s distinct Islamic voice—which speaks of Allah, the grave, judgment, and ritual prayer—the Sikh Gurus elevated these sentiments to the status of Gurbani (Guru’s Word). For a Sikh, bowing before the Guru Granth Sahib means bowing to the wisdom of a Muslim saint as much as to Guru Nanak.5

- The Dialogue of Spirits: The research highlights a dialogue between Guru Nanak and Sheikh Brahm (a successor of Farid) at Pakpattan. This interaction was likely the source of the verses. The conversation wasn’t a debate to convert, but a “colloquy of spirit” to confirm shared truths.13

3.2 Analyzing the Sloks of Farid

Farid’s poetry in the GGS is characterized by intense Vairag (dispassion) and fear of death, themes common in ascetic Sufism.

- Themes of Impermanence: “Farid, the eyes which bewitched the world… I have seen those eyes pecked at by crows”.15 This imagery serves to shatter the devotee’s attachment to the physical body.

- The Gurus’ Response: Interestingly, the Sikh Gurus often juxtaposed their own verses next to Farid’s to modulate the theological message. Where Farid expresses dread of the grave and the harshness of the path (“My body is like a skeleton, crows peck at my soles”), the Gurus respond with verses emphasizing hope, grace (Nadar), and the joy of union with the Beloved, softening the ascetic rigour without negating its truth.13

3.3 Wahdat al-Wujud and Hukam

Scholars trace the influence of the Sufi concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (Unity of Existence) in Sikh thought. The Sikh concept of Hukam (Divine Order) is philologically derived from the Arabic Hukm.

- The Arabic Root: In the Quran, Hukm refers to God’s command or arbitration.

- The Sikh Adaptation: Guru Nanak expands Hukam to mean the all-encompassing cosmic law that governs the universe, karma, and biological processes. “Everyone is subject to the Hukam; no one is beyond it” (Japji Sahib). The research suggests that Nanak’s usage of Hukam preserves the Quranic theme of divine sovereignty while integrating it into the Indic framework of breaking the cycle of rebirth.5

4. Scriptural Authority: Revelation and Hermeneutics

Both traditions are “religions of the Book,” yet their understanding of the nature of scripture and revelation diverges significantly.

4.1 The Quran: The Final Descent

In Islam, the Quran is the uncreated, literal Word of God (Kalam Allah) revealed to the Prophet Muhammad through the Angel Gabriel (Jibril).

- Mode of Revelation: This is Wahi (divine inspiration) in its highest form, or Tanzeel (descent). The text is immutable, and its preservation in the original Arabic is a central tenant of the faith.

- Exclusivity: Islam views the Quran as the Furqan (Criterion) and the “Seal” of previous revelations. While Torah and Gospel are acknowledged, they are seen as corrupted; the Quran is the final correction. This creates a linear theological history.2

4.2 The Guru Granth Sahib: The Living Guru

Sikhism views the Guru Granth Sahib (GGS) not merely as a text, but as the Shabad Guru—the living Teacher.

- Anthological Nature: Unlike the Quran, which was revealed to a single Prophet, the GGS is a compilation of the writings of 6 Sikh Gurus and 30 other saints (Hindu and Muslim). This structure itself is a theological statement: Truth is universal and not the monopoly of one prophet or tribe.5

- Authority: The Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, ended the lineage of human Gurus and vested authority in the scripture. Sikhs do not worship the book as an idol (bibliolatry) but revere the Shabad (Word) contained within it as the manifestation of the Divine Teacher.

4.3 Linguistic Osmosis

The Guru Granth Sahib stands as a linguistic bridge. While written in the Gurmukhi script, its vocabulary is a fusion.

- The Muslim Names of God: The GGS frequently uses Islamic names for God: Allah, Khuda, Rahim (Merciful), Karim (Generous), Parvardigar (Sustainer), Maula (Master), Khasam (Husband/Lord).

- Insight: This usage is not merely syncretic; it is an assertion that the God of the Muslims is the same as the God of the Sikhs. “The mosque and the temple are the same; the Puranas and the Quran are the same. All are the manifestation of the One” (Guru Gobind Singh).1

5. Soteriology: The Architecture of Salvation

While the definitions of God are similar, the mechanisms of salvation (Soteriology) and the understanding of the afterlife (Eschatology) represent the most significant divergence between the Semitic (Islamic) and Indic (Sikh) worldviews.

5.1 Linear vs. Cyclical Time

- Islam (Linear): Human existence is a linear progression: Birth $\rightarrow$ Life $\rightarrow$ Death $\rightarrow$ Barzakh (intermediate state) $\rightarrow$ Yawm al-Qiyamah (Resurrection) $\rightarrow$ Judgment $\rightarrow$ Eternity in Heaven (Jannah) or Hell (Jahannam).

- The Body: The physical body is essential for resurrection, leading to the prohibition of cremation and the importance of burial.

- Judgment: Salvation depends on faith (Iman) and deeds, weighed on the divine scales.2

- Sikhism (Cyclical): Sikhism operates within the Indic framework of Samsara (cycle of birth and death).

- Reincarnation: The soul travels through 8.4 million life forms based on Karma. Human life is the rare opportunity to break this cycle.

- The Goal: The goal is not “Heaven” (which is seen as a temporary station) but Mukti (Liberation)—merging the individual soul (Atma) into the Universal Soul (Paramatma), “like water blending with water”.8

- The Body: The body is a vessel (“chariot of the soul”). Once the soul departs, the vessel is empty; hence, cremation is standard, though not dogmatically mandated (burial at sea or earth is permitted if necessary).7

5.2 Predestination: Qadar and Hukam

Both faiths wrestle with the tension between Free Will and Divine Will.

- Islam: The doctrine of Qadar implies that Allah knows all that will happen. “Inshallah” (If God Wills) governs all future intent. However, humans have “acquired” will (Kasb) to choose between right and wrong, for which they are accountable.

- Sikhism: The doctrine of Hukam is absolute. “By His Command, bodies are created; by His Command, souls come into being.” However, Sikhism emphasizes that the Ego (Haumai) gives the illusion of separation. Recognizing Hukam destroys the Ego, leading to liberation. The insight here is that while Islam emphasizes accountability to the Will, Sikhism emphasizes merging into the Will.5

5.3 Heaven and Hell: Literal vs. Metaphorical

- Islam: Jannah (Paradise) and Jahannam (Hell) are described in vivid, often physical detail in the Quran (gardens, rivers, fire). They are real abodes for the afterlife.

- Sikhism: The GGS uses “Heaven” (Baikunth) and “Hell” (Narak) largely as metaphors for spiritual states. To be in remembrance of God is Heaven; to be trapped in ego and forgetfulness is Hell, right here on earth. The “Day of Judgment” is the constant adjudication of Karma in every moment.7

6. Ethical Praxis and Community Structure

Both Islam and Sikhism are “householder” religions that reject monasticism. They demand that spirituality be expressed through social ethics and community service.

6.1 The Pillars of Faith: A Structural Comparison

| Feature | Islam (Five Pillars) | Sikhism (Three Pillars) |

| Declaration | Shahada (There is no God but Allah…) | Naam Japna (Chanting the True Name) |

| Daily Discipline | Salah (5 Obligatory Prayers) | Nitnem (Daily Liturgy: Japji, Jaap, Rehras) |

| Charity | Zakat (Obligatory 2.5% wealth tax) | Vand Chakko (Sharing earnings / Dasvandh 10%) |

| Livelihood | Implicit in Sharia (Halal earning) | Kirat Karni (Honest Labor) – Explicit Pillar |

| Fasting | Sawm (Ramadan) | Rejected (Emphasis on moderation, not starvation) |

| Pilgrimage | Hajj (Mecca) | Rejected as a ritual necessity (Tirath) |

6.2 Charity: Zakat vs. Vand Chakko and Langar

The redistribution of wealth is central to both.

- Zakat (Islam): A formalized, mandatory tax. It is a purification of wealth and a right of the poor. It is highly structured, with specific categories of eligible recipients (Mustahiqqin).18

- Seva and Langar (Sikhism): Sikh charity goes beyond monetary giving (Dasvandh) to active physical service (Seva). The institution of Langar (community kitchen) is a revolutionary social tool. By making everyone sit in rows (Pangat) on the floor to eat the same food, the Gurus physically dismantled the caste distinctions of purity and pollution. While Zakat purifies wealth, Seva purifies the body and ego.20

- Comparison: Both Zakat and Vand Chakko foster a socialist-leaning community ethos where hoarding is sinful. The Muslim Times notes that “Charity is a central religious duty in both faiths,” linking the Islamic Sadaqah (voluntary charity) to the Sikh concept of Seva.7

6.3 Rejection of Monasticism

Both faiths are explicit in their rejection of renunciation (Sannyasa).

- Islam: “There is no monasticism in Islam” (Hadith). The Prophet Muhammad lived as a husband, father, trader, and statesman.

- Sikhism: Guru Nanak scolded the Siddhas (yogis) who hid in the mountains: “The world is burning, and you hide in the caves?” The ideal Sikh is a Sant-Sipahi (Saint-Soldier) who lives in the world like a lotus flower in muddy water—untouched by attachment but present in the environment.7

7. Gender, Society, and the Body

The social coding of the human body and the status of women reveal both the revolutionary aspects of these faiths and their historical divergences.

7.1 Gender Equality: Scriptural vs. Traditional

- Islam: The Quran introduced radical rights for women in 7th-century Arabia (right to inheritance, divorce, property). However, traditional jurisprudence maintains distinct gender roles. Men are often viewed as protectors (Qawwamun), and gender segregation in prayer spaces is normative. Women generally do not lead mixed-congregation prayers.2

- Sikhism: Guru Nanak openly challenged the notion of female inferiority. “From woman, man is born… how can she be called inferior, she who gives birth to kings?” (GGS, Ang 473).

- Ritual Equality: Sikhism abolished the concept of menstrual impurity (Sutak). Women can lead prayers, perform Kirtan (hymn singing), and act as Granthis (custodians of scripture).

- The Kaur Identity: Guru Gobind Singh gave women the surname Kaur (Princess/Lioness), giving them an identity independent of their fathers or husbands.23

- Insight: While scriptural equality is high in Sikhism, cultural practice in Punjab often lags behind, influenced by patriarchal norms common to the region’s agrarian culture, a challenge shared by South Asian Muslims.7

7.2 The Body: Hair and Circumcision

- Circumcision: A major marker of identity. Muslims practice male circumcision (Khitan) as a Sunnah of Abraham. Sikhism strictly forbids it, viewing it as an alteration of the God-given form and a “blind ritual”.2

- Hair (Kesh):

- Muslims: Men are encouraged to keep beards (often trimmed to a fist length) and trim mustaches. Women are required to cover hair (Hijab).

- Sikhs: Initiated Sikhs (Khalsa) are forbidden from cutting any hair on the body. The turban (Dastar) is mandatory for men (and optional but encouraged for women) as a crown of sovereignty. For Sikhs, hair is not just a symbol but a biological affirmation of abiding by God’s Will (Raza).2

7.3 Dietary Laws: The Meat Controversy

- Halal: Muslims must eat meat slaughtered by cutting the jugular vein while reciting God’s name, draining the blood.

- Kutha: Sikh Rehat (code) explicitly forbids eating Kutha meat. Kutha is defined as meat slaughtered with a ritual prayer (specifically targeting Halal and Kosher). This prohibition was historically a declaration of independence from Islamic political hegemony.

- Jhatka: Most meat-eating Sikhs prefer Jhatka (single-stroke slaughter) to minimize animal suffering, though many Sikhs practice lacto-vegetarianism.25

- Intoxicants: Both faiths strictly ban alcohol (Khamr). The Muslim Times highlights this shared prohibition as a key similarity. However, a nuance exists: some traditional Sikh warrior sects (Nihangs) consume cannabis (Sukha or Bhang) in liquid form as a “battle sacrament,” a practice that contrasts with the strict Islamic prohibition of all intoxicants.7

8. Political Theology: Sovereignty and Just War

Islam and Sikhism are arguably the two most “political” religions in the Indian context, as neither accepts a separation between the spiritual and the temporal (Miri-Piri in Sikhism, Din wa Dunya in Islam).

8.1 Jihad and Dharam Yudh

The concept of “Holy War” is often misunderstood in both.

- Jihad (Islam): Linguistically “struggle.”

- Greater Jihad: The internal struggle against the lower self (Nafs).

- Lesser Jihad: Martial defense of the community (Ummah) against oppression or aggression. Classical jurisprudence laid out strict rules of engagement (no killing non-combatants, destroying crops, etc.).28

- Dharam Yudh (Sikhism): “War for Righteousness.”

- The Doctrine: codified in the Zafarnama by Guru Gobind Singh: “When all other means of conflict resolution fail, it is righteous to draw the sword.”

- Key Distinction: Unlike some interpretations of offensive Jihad (expansion of the Islamic state), Dharam Yudh is strictly defensive and secular in objective—it is fought to protect the religious freedom of all, not just Sikhs. Guru Tegh Bahadur famously gave his life to protect the rights of Kashmiri Pandits (Hindus) to wear their sacred threads, a unique example of a prophet dying for the rights of another religion.1

8.2 Sovereignty: Khilafat vs. Halemi Raj

- Islam: Historically aspired to the Caliphate (Khilafat), a transnational polity governed by Sharia.

- Sikhism: Aspired to Khalsa Raj or Halemi Raj (Kingdom of Humility). When Sikhs established an empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1799–1839), it was secular. Muslims were generals, ministers, and judges. The mosques were state-funded alongside Gurdwaras. This indicates a political theology that values pluralism over theocratic homogenization.

9. Insights from Contemporary Comparative Discourse (The Muslim Times)

Incorporating specific insights from the article “Similarities between Islam and the Sikh Religion” 7, we find a modern attempt to bridge the divide by focusing on functional similarities rather than theological hair-splitting.

9.1 Shared Structural “DNA”

The article identifies several key convergences that define both communities:

- Rejection of Idolatry: It emphasizes that both faiths classify idol worship as “futile” and “delusional.” This shared iconoclasm sets them apart from the polytheistic traditions of India.

- Opposition to Grave Worship (Qabar Parasti): The article astutely notes that while folk practices in South Asia often involve worshipping at the shrines of Saints (Pirs), both orthodox Islam and Tat Khalsa Sikhism condemn this. They urge the believer to connect directly with the Creator, bypassing the “dead.”

- No Ordained Priesthood: A critical insight is the democratic nature of worship. Neither religion requires a priest to perform rites. Any learned Muslim can lead prayer; any learned Sikh can read the Guru Granth Sahib. This rejects the Brahmanical necessity of an intermediary.

- Morality of Speech: The article highlights a shared ethical focus on avoiding “worthless talk” (Fuhish in Islam, Fokat in Sikhism) and slander, viewing speech as a spiritual energy that must be conserved.

- Accountability: It bridges the gap between Karma and Judgment Day by framing them both as systems of “Accountability”—the principle that “As you sow, so shall you reap” is universal to both.

9.2 The “Militarized” Religion Argument

The article bravely categorizes both as “militarized religions.” This is not a pejorative but an acknowledgement that both faiths refuse to be passive spectators to injustice. They both authorize the use of force to defend the weak, distinguishing them from absolute pacifist traditions like Jainism or early Christianity. This shared “martial spirit” creates a psychological affinity between Sikhs and Muslims (specifically Pashtuns and Punjabis) that has historically resulted in both fierce enmity and deep mutual respect.

10. Thematic Epilogue: Diverging Rivers, One Ocean?

The comparative study of Islam and Sikhism reveals a relationship that is at once intimate and distinct. They are like two mighty rivers flowing from different glaciers—one from the Semitic desert revelations, the other from the Indic meditative traditions—that converge in the landscape of the Punjab.

The Convergence:

They meet in their fierce devotion to the Formless One (Nirankar/Allah). They share a disdain for empty ritualism, caste hierarchy, and idolatry. They both champion the “householder-warrior” ideal, rejecting the ascetic who flees the world. The inclusion of Baba Farid in the Sikh scripture stands as an eternal testament that at the mystic level, the boundaries dissolve.

The Divergence:

Yet, they remain distinct. Islam’s path is linear, legalistic, and centered on the finality of Prophetic revelation and the Resurrection. Sikhism’s path is cyclical, musical, and centered on the living Guru and the breaking of Reincarnation. Islam seeks to submit to the Will of God; Sikhism seeks to dissolve into it.

Final Synthesis:

Perhaps the profoundest insight is that Sikhism is not, as early Orientalists claimed, a “syncretism” of Hinduism and Islam. Rather, it is a unique revelation that validates the truths found in Islam (Monotheism, Equality, Justice) while rejecting its exclusivism. It accepts the Sufi but critiques the Mullah. It accepts Allah but rejects the idea that He is found only in Mecca. In doing so, Sikhism offers a theological framework that honors the Islamic experience while charting its own distinct course towards the Divine.

For the modern world, the dialogue between these two faiths offers a model of how distinct religious identities can share a common ethical and spiritual grammar—a reminder that while the rituals may differ, the Light (Noor/Jot) is the same.

Appendix: Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Theological Concepts

| Concept | Islam | Sikhism |

| Primary Name of God | Allah | Waheguru / Akal Purakh |

| Nature of Revelation | Wahi (Descent of Word) | Shabad (Inner Sound/Word) |

| Holy Book Status | Final Word of God | Living Guru |

| Prophethood | Finality (Seal of Prophets) | Lineage of 10 Gurus, then Granth |

| Idolatry | Strictly Forbidden (Shirk) | Strictly Forbidden (Manmat) |

| Creation Theory | Kun Faya Kun (Be, and it is) | Kita Pasao (One expansive command) |

Table 2: Social and Dietary Practices

| Practice | Islam | Sikhism |

| Caste System | Rejected (Theologically) | Rejected (Theologically & Socially) |

| Clergy | No official priesthood (Imams are leaders) | No official priesthood (Granthis are custodians) |

| Circumcision | Obligatory (Sunnah) | Forbidden |

| Meat | Halal (Ritual slaughter) | Jhatka (Non-ritual) / Vegetarian |

| Alcohol | Forbidden (Haram) | Forbidden (Bajjar Kurahit) |

| Tobacco | Disliked/Forbidden (Makruh/Haram) | Strictly Forbidden (Cardinal Sin) |

| Burial/Cremation | Burial only | Cremation preferred |

Table 3: Eschatology (The End Times)

| Feature | Islam | Sikhism |

| Death | Soul waits in Barzakh | Soul transmigrates immediately |

| End of World | Qiyamah (Apocalypse) | Dissolution (Pralaya) and Recreation |

| Final Goal | Jannah (Paradise) | Mukti (Merger with God) |

| Judgment | Day of Judgment | Constant adjudication of Karma |

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment