Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD

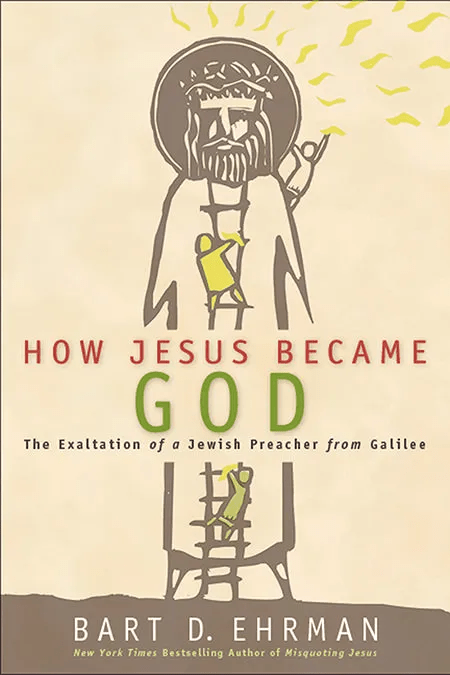

Introduction – From Galilee to Godhood: Bart D. Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee is a scholarly yet accessible exploration of one of the most remarkable transformations in religious history: how Jesus of Nazareth, a charismatic apocalyptic preacher, was eventually acclaimed by his followers as divine ia801209.us.archive.org ia801209.us.archive.org. Ehrman, a renowned New Testament historian and self-described agnostic, approaches this question from a secular-critical stance, treating Jesus as a historical figure rather than assuming any inherent divinity. The book’s central thesis is that neither Jesus nor his disciples considered him divine during his lifetime, but after his crucifixion the disciples’ experiences—particularly their visionary belief in his resurrection—prompted them to re-evaluate Jesus’ identity and gradually elevate him to divine status credohouse.org ia801209.us.archive.org. This review will delve into the major themes and arguments of Ehrman’s work, following the historical development of early Christian beliefs about Jesus’s divinity. We will examine Ehrman’s evidence that earliest Christology began as an “exaltation” belief (Jesus as a man exalted by God to divine status) which then evolved into an “incarnation” belief (Jesus as a pre-existent divine being who became human)credohouse.orgia801209.us.archive.org. Along the way, we will incorporate Ehrman’s own words and engage with reactions from other scholars—both those who find his arguments illuminating and those who criticize his conclusions.

Divine Continuum in the Ancient World – Greco-Roman and Jewish Context

A key foundation of Ehrman’s book is that in the ancient world, the boundary between human and divine was permeable – far more fluid than many modern people assume catholic.com. In Greco-Roman pagan culture, it was not uncommon to believe that gods could take on human form and that exceptional humans could be elevated to godlike status. Emperors like Julius Caesar and Augustus were regarded as gods or “sons of God” after their deaths (and even, in Augustus’s case, during his lifetime) ia801209.us.archive.org ia801209.us.archive.org. Stories abounded of heroes or holy men who became deities. Ehrman emphasizes that the category of “divinity” was “elastic”: ancient people imagined a continuum of divine beings, from minor divinities just above humans up to the One God at the pinnacle credohouse.org selfawarepatterns.com. Even within Second Temple Judaism, which was monotheistic, ideas of a spectrum of divine agents existed. As Ehrman succinctly puts it, “Within Judaism we find divine beings who temporarily become human, semidivine beings who are born of the union of a divine being and a mortal, and humans who are, or who become, divine.” goodreads.com. In other words, first-century Jews did not have a modern, absolutist view that no human could ever share in divinity; they had concepts like principal angels, exalted patriarchs, and God’s “son” (e.g. the king or messiah) that blurred the lines between human and divine status ia801209.us.archive.org selfawarepatterns.com.

Ehrman explores how this cultural milieu made it conceivable for Jesus’s followers to regard him as divine after the fact catholic.com. He opens the book with illustrative parallels, such as the case of Apollonius of Tyana, a first-century miracle-worker whose legend claimed he was a son of God who cheated death catholic.com. Such examples set the stage for Ehrman’s argument: in a world where **“gods” and **“men” frequently intersected, the apostles’ belief that their beloved teacher had become “God” was not an impossible leap. (Critical reviewers have pointed out that some of Ehrman’s pagan parallels, like Apollonius, are based on later, less reliable sources than the Gospels catholic.com. Nonetheless, the broader point stands that the ancient mindset allowed for god-men and divine exaltation far more readily than a modern skeptic might assume.)

Read further in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment