Epigraph:

Surely, the Believers, and the Jews, and the Christians and the Sabians — whichever party from among these truly believes in Allah and the Last Day and does good deeds — shall have their reward with their Lord, and no fear shall come upon them, nor shall they grieve. (Al Quran 2:62)

Presented by Dr. Atif Suhail, Dallas, Texas

Abstract

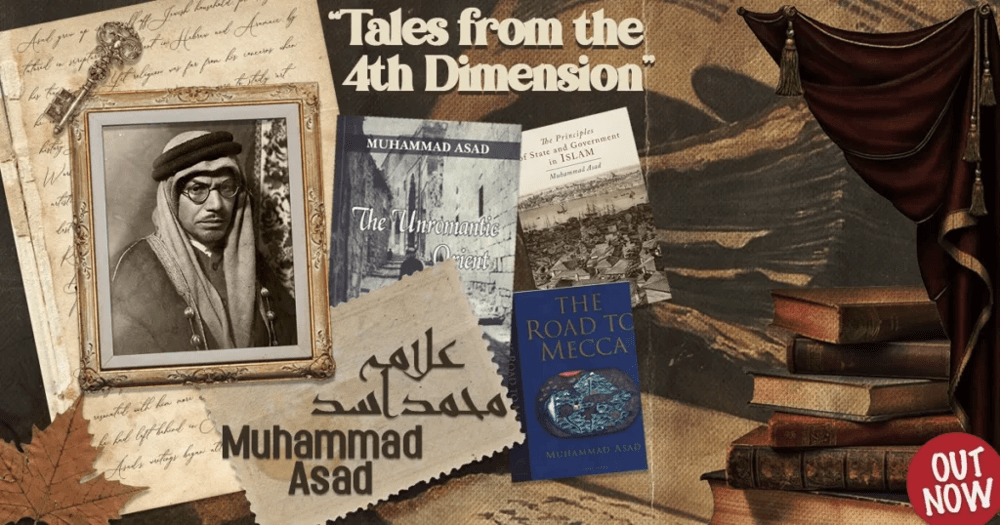

Muhammad Asad (born Leopold Weiss, 1900–1992) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish intellectual who famously embraced Islam and went on to become one of the 20th century’s most influential Muslim thinkers. A journalist, traveler, Quran translator, and diplomat, Asad’s life was a bridge between Judaism and Islam, and between the East and West. This biography traces his remarkable journey – from his upbringing in a Jewish family in Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine), through his spiritual transformation and conversion to Islam in 1926, to his pivotal role in the intellectual foundation of Pakistan and his enduring literary contributions. We explore his early life and the questions that led him from the Torah to the Qur’an, his advocacy for interfaith understanding and religious tolerance, and his legacy as a “religious bridge-builder.” Key aspects include his modernist approach to Islamic thought (emphasizing reason and ijtihād), his contributions to Pakistan’s formative years (as a close associate of Muhammad Iqbal and as Pakistan’s first UN envoy), and his major works such as The Road to Mecca and The Message of the Qur’an. Throughout, Asad’s own words about Islam’s universality, the shared heritage of Judaism and Islam, and the importance of tolerance are highlighted. His life story reads like an invitation – especially to his fellow Jews and all “People of the Book” – to discover the profound spiritual kinship and ethical common ground that Islam offers.

Early Life and Conversion from Judaism to Islam

Leopold Weiss was born on July 2, 1900, into an Austrian-Jewish family in the city of Lemberg (Lviv) in the Austro-Hungarian Empireirfront.orgtribune.com.pk. He came from a lineage of rabbis – his grandfather was an orthodox rabbi – and although his parents were not strictly observant, they ensured he received a thorough Jewish educationtrtworld.comtabletmag.com. By his bar-mitzvah age, young Leopold could read Hebrew fluently and even converse in it, and had a fair grasp of Aramaictrtworld.com. This early immersion in Tanakh (Hebrew Scriptures) and rabbinical thought honed his mind for theological inquiry and would later aid his understanding of the Qur’antrtworld.com.

However, Weiss’s teenage and early adult years were marked more by secular explorations than by religion. After the devastation of World War I, he entered the University of Vienna in 1920 to study art history, dabbling in philosophy and immersing himself in the bohemian intellectual circles of Weimar-era Viennatrtworld.compakasiayouthforum.com. Europe was in a moral and spiritual crisis – the old certainties had been shattered by war and social upheavaltrtworld.com. Like many of his generation, Weiss hungered for meaning. He frequented cafés where Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories and new artistic ideas were debatedtrtworld.com. But academia failed to captivate him; restless and idealistic, he dropped out and moved to the vibrant metropolis of Berlin in the early 1920strtworld.compakasiayouthforum.com.

In Berlin, Weiss worked briefly as a wire-service journalist and scriptwriter, even scoring an interview with Maxim Gorky’s wifetrtworld.com. Yet the glitter of post-war European modernity felt hollow to him. He saw around him a society materially rebuilding but spiritually adrift – a generation of people “vacant” and unhappy despite high culture and scientific progresstrtworld.com. Years later, he would recall how Europe’s affluence had not bought inner peace: “Europe’s high culture, the advancement of sciences and material progress weren’t enough to make its people happy”trtworld.com. He began to feel that the salvation of modern humanity might lie outside the Western paradigmtrtworld.com.

At 22, Weiss embarked on a journey that would change his life. In 1922 he traveled to British-ruled Palestine (at his psychoanalyst uncle’s invitation) and encountered the Middle East for the first timetrtworld.com. Amid the tense crossroads of Zionism and Arab nationalism, Weiss found himself unexpectedly enchanted by the Arab way of life. The simple tents of Bedouin nomads, their hospitality and honor, reminded him of the biblical patriarchs he’d studied as a boy. “The local Muslim Arab Bedouin with his honesty, simplicity and his camels and camps was closer to the Hebrew characters he had studied as a boy in the Old Testament than a modern European Jew,” one account notes of Weiss’s impressiontrtworld.com. He felt he was almost meeting the living spirit of Abraham and Moses in the desert. By contrast, the organized political project of Zionism – European Jews attempting to create a Western-style nation-state in Palestine – repelled him. He questioned Zionist leaders like Chaim Weizmann directly, asking on what moral basis immigrants (aided by colonial powers) could claim a land inhabited by Arabs for centuriestabletmag.comtabletmag.com. He later wrote, “I conceived from the outset a strong objection to Zionism… I considered it immoral that immigrants… should come from abroad with the avowed intention of attaining majority in the country and thus to dispossess the people whose country it has been since time immemorial.”tabletmag.com. This sense of justice for the oppressed and discomfort with tribal nationalism would characterize his outlook thereafter.

Weiss fell in love with Arab culture before even accepting Islam. He spent the next few years traveling across Mandatory Palestine, Transjordan, Syria, Iraq, Persia (Iran), and Egypt as a correspondent for the renowned Frankfurter Zeitung. These travels (later recounted in his first book, Unromantic Orient) exposed him to the wider Islamic world and sharpened his insight into Muslim societies’ struggles under colonial ruleirfront.orgtrtworld.com. He saw, for example, the brewing injustice in Palestine: “Arabs in their own homeland treated as strangers, and Jews coming with European methods and aims… The Arabs’ firm resistance… was, to my eyes, not wrongful; rather, it was the Arabs who were being wronged and pushed into a legitimate defensive fight.” (as he later reflected)goodreads.comgoodreads.com. Such observations deepened his empathy for Muslims and his critique of European imperialism.

By 1926, after four years immersed in Middle Eastern life, Leopold Weiss reached a personal crossroads. A famous story – often told, including by Asad himself – encapsulates the moment of his conversion to Islam. Riding on an Berlin U-Bahn train in September 1926, he found himself gazing at the weary, joyless faces of Europeans around him. Despite living in comfort, they appeared, to his eyes, “as if they are in agony”irfront.orgirfront.org. This stark image of spiritual emptiness haunted him. Returning to his apartment, Weiss picked up a copy of the Qur’an he’d been reading. His eyes fell on a chapter called “At-Takāthur” (“Greed for More and More”), and as he read, he felt the verses speak directly to the malaise of modern materialism: “You are obsessed by greed for more and more until you go down to your graves… you will come to know the truth…” (Qur’an 102:1-8)irfront.orgirfront.org. Weiss later described what happened next: “The Qur’an literally shook in my hands, and I was speechless. It was an answer: an answer so decisive that all doubt was suddenly at an end. I knew now, beyond any doubt, that it was a God-inspired book I was holding in my hand.”irfront.orgirfront.org. In that moment, he felt a serene certainty wash over him – as if the truth had stolen into his heart like a thief in the night (to use his poetic phrase) but to remain there foreverirfront.org.

Without delay, Weiss sought out a Muslim friend in Berlin and declared his acceptance of Islam, pronouncing the shahādah (the testimony of faith)irfront.org. He was 26 years old. He adopted the name “Muhammad Asad”, a choice rich with layered meaning: Muhammad in honor of Islam’s Prophet, and Asad, meaning “lion,” both as a translation of his birth name Leopold (derived from Latin Leo) and his Hebrew name Aryeh, and as a symbol of spiritual strengthirfront.orgtabletmag.com. A few weeks later, his wife Elsa (an artist 15 years his senior who had traveled with him) also embraced Islamirfront.org. Asad later reflected on his leap of faith in lyrical terms: “After all, it was a matter of love… Islam came over me like a thief in the night; but unlike a thief, it entered to remain for good.”irfront.org. What he “loved” in Islam was not an abandonment of his past, but a fulfillment of all he had been seeking – a return to pure monotheism and moral clarity. Indeed, far from feeling he had betrayed his ancestors, Asad believed he had rediscovered the God of Abraham anew through Islam.

Why Islam and not Christianity? This was a question many asked, including a learned Jesuit priest Asad met not long after his conversion. In a remarkable anecdote Asad himself recounted, the Jesuit expressed puzzlement that as a Jew by birth, Weiss/Asad had “logically” skipped over Christianity and “jumped” to Islamreddit.com. Asad’s answer encapsulated what drew him to Islam’s theology. He told the priest he would consider converting to Christianity on the spot – if the priest could satisfactorily explain the doctrine of the Trinityreddit.comreddit.com. The Jesuit admitted that the Trinity was a “mysterium” beyond rational explanation, graspable only through blind faithreddit.com. “That,” Asad replied, “was the reason I became Muslim. You tell me to gain faith first and then I will understand. My religion tells me: use your reason, and then you will gain faith.”reddit.com. This powerful exchange highlights Asad’s conviction that Islam does not demand the believer to abandon intellect. In Islam he found a unity of God free of convoluted dogmas, a faith that appealed directly to reason and the innate human sense of truth. The Qur’an itself invites reflection, addressing itself, as Asad loved to quote, to “those who think.” It was this harmony of intellect and faith that made Islam feel like a natural home for his restless, seeking soul – “a blinding sunrise of fulfillment”, as he would describe his spiritual awakeninggoodreads.com.

His decision to convert was also a conscious “revolt against the relativism, consumerism, and confusion of postwar Europe”criticalmuslim.com. Asad framed his embrace of Islam as part of a broader critique of the West’s loss of spiritual center. Europe, in his view, had become trapped in materialistic excess and moral relativity after the war, whereas Islam offered a clear unitary purpose for life. Europe’s secular modernity seemed to him an era of crisis and decay, and he was not alone in this sentiment. (In fact, Asad later noted that some of the same disillusionment with the West was driving European Jews toward Zionism – yearning for rootedness and meaning – but whereas they sought answers in a nationalist project, he found the answer in Islam’s ummah)criticalmuslim.comcriticalmuslim.com. In Islam at the Crossroads (one of his early writings), he warned Muslims not to follow blindly the Western path of secularism, which he believed had led to social and spiritual disarray in Europecriticalmuslim.com. The young Asad thus “revolted” against both European secularism and what he perceived as Jewish particularism, choosing instead Islam’s universalismtabletmag.comtabletmag.com. “For Asad, Islam is universalist and Judaism is particularistic,” writes one biographer, noting that Asad viewed the Jewish notion of a “chosen people” as a narrow, tribal concept, whereas Islam’s message was meant for all humanitytabletmag.commohammedamin.com. This was not a condemnation of his ancestral faith per se, but a critique of any worldview that restricted salvation or truth to a single lineage or group. By embracing Islam, Asad felt he had entered a faith tradition that fulfilled the ethical monotheism of Judaism while shedding any nationalist or ethnic exclusivity.

It is noteworthy that decades later, in 2008, the city of Vienna – where Leopold Weiss once roamed as a lost student – named a square in front of the United Nations after Muhammad Asad, explicitly honoring him as a “religious mediator” who built bridges between faithsdawn.commeforum.org. The trajectory from **Lemberg’s son of rabbis to an Islamic luminary was indeed extraordinary. But as we shall see, Asad’s conversion was only the beginning of a lifelong mission to connect Islam with the West and to articulate an Islam that could speak to all people – Jews, Christians, and secular modernists alike – as a force for tolerance, intellectual inquiry, and universal values.

A Modernist Islamic Thinker: Intellectual Contributions and Philosophy

From the moment of his conversion, Muhammad Asad devoted himself to a deep study of Islam’s scripture, history, and intellectual tradition. Unencumbered by formal seminary schooling, he was largely self-taught – and in some ways this became a strength. Asad approached the Qur’an and Hadith with fresh eyes, armed with profound Scriptural knowledge from his Jewish upbringing and a critical journalist’s mind. He early on gravitated toward Islamic modernist and reformist ideas, making him part of a burgeoning 20th-century trend that sought to reconcile Islamic teachings with the modern world’s challenges.

One of Asad’s core beliefs was the necessity of “going back to the sources” – the Qur’an and the authentic example of the Prophet – and applying reasoned interpretation (ijtihād) to derive guidance for contemporary lifeirfront.orgirfront.org. He observed that many Muslim societies had fallen into stagnation by merely imitating classical scholars (a practice known as taqlīd or blind following) instead of exercising independent reasoning as earlier generations didirfront.orgirfront.org. In Cairo, where he spent time learning Arabic after his conversion, Asad befriended Shaykh Mustafa al-Marāghī, a student of the reformist Imam Muhammad ‘Abduhirfront.org. Through al-Marāghī, he became aware of how even venerable institutions like Al-Azhar University had grown intellectually “sterile” – endlessly repeating medieval opinions without fresh insightirfront.org. Asad noted with some alarm that many Muslims treated the works of past scholars almost like infallible texts, forgetting that those scholars never intended their views to ossify into dogmairfront.orgirfront.org. “Just as some saints and scholars would be surprised to see their graves made into shrines, many will also be shocked to see how their words were immortalized,” Asad quipped, lamenting the “fossilization” of Islamic thought under rigid taqlīdirfront.orgirfront.org.

He therefore issued a strong rebuke of blind imitation. In his view, Islamic civilization’s decline was not due to any flaw in Islam itself but due to Muslims having ceased to think for themselves and to live up to Islam’s teachings dynamicallygoodreads.comgoodreads.com. Asad often pointed out that the Qur’an repeatedly challenges people to use their intellect. For instance, he would cite verses like: “Will you not use your reason?” and emphasize that “The Qur’an is Islam; everything else is human interpretation and history”irfront.orgirfront.org. In one eloquent passage, Asad wrote: “My own observations had convinced me that the mind of the average Westerner held an utterly distorted image of Islam. What I saw in the pages of the Koran was not a ‘crudely materialistic’ world-view but, on the contrary, an intense God-consciousness that expressed itself in a rational acceptance of all God-created nature: a harmonious side-by-side of intellect and sensual urge, spiritual need and social demand… It was obvious to me that the decline of the Muslims was not due to any shortcomings in Islam but rather to their own failure to live up to it.”goodreads.comgoodreads.com. This reflection, drawn from The Road to Mecca, crystallizes Asad’s guiding philosophy: Islam is inherently balanced and comprehensive – it integrates the life of the spirit with the life of the mind, personal morality with social justice. If Muslims were falling behind, it was because they had strayed from this holistic practice of Islam, not because Islam’s teachings were deficient.

Knowledge (’ilm) was a sacred trust in Asad’s eyes. He loved to recount how early Muslims, driven by the Prophet’s sayings – “Striving after knowledge is a most sacred duty for every Muslim (man and woman)” and “The ink of the scholar is more precious than the blood of martyrs” – pioneered advancements in science, medicine, and philosophygoodreads.comgoodreads.com. Unlike Christendom, where scientific discoveries often clashed with dogma, the Islamic ethos encouraged exploration of the natural world as a form of worship. “Throughout the whole creative period of Muslim history… science and learning had no greater champion than Muslim civilization,” Asad observed, detailing how Qur’anic verses inspired disciplines from biology to astronomygoodreads.comgoodreads.com. He reveled in examples: centuries before Copernicus, Muslim astronomers posited that the earth was round and rotated on its axisgoodreads.comgoodreads.com; motivated by the Qur’anic emphasis on curing disease, Muslim physicians founded hospitals and wrote medical encyclopedias. For Asad, these achievements were not just historical trivia – they were proof that Islam and progress are fully compatible, provided Muslims remain faithful to the spirit of inquiry their faith demands. “If we had always followed that principle of Islam which imposes the duty of learning and knowledge on every Muslim man and woman, we would not have to look today towards the Occident for an acquisition of modern sciences,” Asad wrote pointedlytrtworld.comtrtworld.com.

Central to Asad’s intellectual contribution was his emphasis on ijtihād, or fresh reasoning, in the modern context. He believed that while the Qur’an and the Prophet’s Sunnah contain eternal principles, their application to governance, economics, and social issues requires flexibility with changing timesirfront.orgirfront.org. In Asad’s words, history can only give advice, not rule us; it is not to be replicated wholesale in today’s societyirfront.orgirfront.org. For instance, he noted that early Muslim scholars devised laws under vastly different conditions (often under absolute monarchies), and that slavishly imitating those medieval rulings could hamstring Muslims in the presentirfront.orgirfront.org. Citing contemporary reformers like Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi, Asad argued that Islam deliberately left “open spaces” (faraghāt) – areas where no fixed rule is given – precisely so that Muslims can legislate through reason and consensus in accordance with the Qur’an’s spiritirfront.orgirfront.org. “If Islam is the final divine revelation to humanity,” Asad (and Ghannouchi) maintained, “it is only appropriate that no fixed prescriptions are given for matters that are of changing nature… Muslims can exercise their ijtihād to devise suitable solutions for emerging problems, which makes [Islam] fit for all times and places.”irfront.orgirfront.org.

Historically, Asad aligns with a line of Islamic modernists and revivalists. He drew inspiration from scholars like Muhammad ‘Abduh of Egypt and Jamaluddin al-Afghani, who championed rationalism and reform, as well as from earlier figures like Ibn Taymiyyah and Ibn Hazm, who emphasized going back to scriptural puritycriticalmuslim.comcriticalmuslim.com. In fact, Asad held the medieval Andalusian jurist-philosopher Ibn Hazm in such esteem that he called him “Imām al-A’ẓam” (the greatest Imam)irfront.org. From Ibn Hazm, he likely absorbed a certain rigor in sticking to clear texts over human conjecture. Yet Asad was not anti-tradition per se; he was against uncritical tradition. Notably, he was not one of those who reject the Hadith or Sunnah (as some extreme modernists did). In fact, one of his early scholarly projects was an annotated translation of the Prophet’s sayings. In the late 1930s, he undertook to translate Sahih al-Bukhari, the foremost Hadith collection, into English – an ambitious project never before attemptedirfront.orgirfront.org. He published part of it as “The Early Years of Islam” in 1938 in Lahoreirfront.org. Although this translation was left incomplete (with manuscripts lost during tumultuous times), it underscores that Asad valued Hadith as a source of guidance – only he insisted on understanding them contextually and critically, not treating every report or later commentary as beyond questionirfront.orgirfront.org.

One area where Asad’s interpretive boldness drew both praise and controversy was his Qur’anic commentary, especially on interfaith relations and socio-political issues. He consistently highlighted the Qur’an’s inclusive stance toward righteous Jews, Christians, and others – opposing any interpretation that preached bigotry or exclusivism. For example, commenting on the Qur’anic verse 2:62 (“Verily, those who believe [in the Qur’an], and those who are Jews, and the Christians, and the Sabians – all who believe in God and the Last Day and do righteous deeds – shall have their reward with their Lord…”), Asad wrote that this passage “lays down a fundamental doctrine of Islam. With a breadth of vision unparalleled in any other religious faith, the idea of ‘salvation’ is here made conditional upon three elements only: belief in God, belief in the Day of Judgment, and righteous action in life.”mohammedamin.com. He explained that this was stated in the Qur’an as a corrective to “the false Jewish belief that their descent from Abraham entitles them to be regarded as ‘God’s chosen people’”mohammedamin.commohammedamin.com. Thus Asad directly refuted notions of ethnocentric salvation, whether Jewish or even Muslim – emphasizing that Islam does not claim a monopoly on Paradise, but rather offers a universal formula: sincere faith in one God and good deeds. Such commentary endeared him to many who saw Islam as a tolerant faith, though it ruffled ultra-conservatives who preferred a narrower interpretation. Indeed, Islamophobes and Muslim hardliners alike sometimes attacked Asad’s inclusive interpretation of verses like 2:62, with the latter even alleging such verses were “abrogated” – a claim Asad strongly rejectedcesnur.orgmohammedamin.com. To him, the Qur’an’s message of “no fear for them nor shall they grieve” for righteous people of any background was incontrovertible and in line with Islam’s self-description as a confirmation of previous revelations, not a negationmohammedamin.commohammedamin.com. (Notably, Asad’s translation of Qur’an 3:85 renders “islām” as “self-surrender unto God,” which he points out “is of course perfectly capable of applying to Christians and Jews as well as to Muslims” – subtly reinforcing that “Islam” in the Qur’anic sense is a universal submission to God, not the label of a single communitymohammedamin.com.)

Another instance of Asad’s principled, context-driven approach is his handling of the contentious Qur’anic verses that some have misused to vilify Jews (such as those about a group being turned into apes for breaking the Sabbath). Asad painstakingly explained that these verses do not generalize about Jews at all – they refer to a specific community’s sin, and even the transformation into “apes” he interpreted as metaphorical for moral degradation, citing early Islamic scholars to support this viewthequran.lovethequran.love. He notes that a classical commentator, Mujāhid, explicitly said “they were not really transformed into apes; this is but a metaphor… the expression ‘like an ape’ is often used in Arabic to describe a person who cannot restrain his gross appetites.”thequran.love. By publicizing such interpretations, Asad provided a counter-narrative to both anti-Semitic readings of the Qur’an and to extremists who try to weaponize scripture. “There is no verse in the Quran that says ‘Jews are apes and monkeys,’” an article summarizing Asad’s view concludes, adding that “Islam does not command Muslims to hate anyone, Jewish or otherwise.”thequran.lovethequran.love. This exemplifies Asad’s interfaith sensitivity – he consistently used his scholarship to build bridges, arguing that Islam, properly understood, holds no inherent animosity toward Judaism or Christianity. Quite the opposite: Islam venerates the same prophets and confirms the same God, differing largely in its universalist outlook and finality of prophethood in Muhammad.

In the realm of political thought, Asad’s major intellectual contribution was his vision for an “Islamic state” that marries Islamic principles with modern governance. His 1961 book The Principles of State and Government in Islam is a slim but groundbreaking treatise where he lays out the foundations of an Islamic polity in contemporary termsirfront.orgirfront.org. Writing shortly after the birth of Pakistan (a state whose emergence he had actively supported), Asad admitted that existing Islamic jurisprudence did not have ready-made blueprints for running a modern nation-stateirfront.orgirfront.org. The classical heritage discussed the Caliphate and certain general principles, but never faced the complexities of constitutions, parliaments, and nation-states as we know them. Therefore, Asad engaged in creative ijtihād to articulate how shura (consultation), ijma (consensus), and other Islamic concepts could translate into democratic governance in the modern agetrtworld.comtrtworld.com. Democracy, he argued, is not only compatible with Islam but demanded by it – rulers must be accountable to the community of believers, and legislation (insofar as it does not contravene divine law) can be enacted through the collective deliberation of those believers’ representativestrtworld.comtrtworld.com. He vehemently refuted the notion (held by some extremists) that Islam requires a theocracy or that democracy is “un-Islamic”trtworld.comtrtworld.com. Instead, he showed from historical precedents and Quranic values that consultative, consensual governance was the Prophetic ideal. He also firmly maintained that non-Muslim citizens of an Islamic state must have their civil rights respected and be equal before the lawtabletmag.comtabletmag.com. Asad’s Islamic state was “thoroughly modern but inspired and informed by religious principles” – a far cry from later militant visionstabletmag.comtabletmag.com. In fact, he envisioned a state where women would be treated as equals and religious minorities protectedtabletmag.comtabletmag.com, positions he backed up with Quranic reasoning.

It is significant that Asad’s works laid intellectual groundwork that influenced other Islamist thinkers, even if indirectly. He had close dialog with Allama Muhammad Iqbal (the poet-philosopher who dreamed of Pakistan) and with Abul A’la Maududi (founder of Jamaat-e-Islami)trtworld.com. Sayyid Qutb of Egypt, a leading Islamist ideologue, was an admirer of Asad; Qutb even titled a chapter of his book Social Justice in Islam as “Islam at the Crossroads” in homage to Asad’s essaytrtworld.comtrtworld.com. However, Asad’s own approach remained more nuanced and humanistic than many post-1970s “Islamists.” He never condoned violence or coercion; rather, he believed in reform through education, dialogue, and example. He was, as one Austrian official described at the Vienna plaza inauguration, a “religious mediator who always spoke in favor of religion on the basis of democratic values and uniting elements.”meforum.org.

In summary, Muhammad Asad’s intellectual legacy in Islam is that of a renaissance figure – a man who called Muslims back to the Qur’an’s original light (which he saw as rational, just, and merciful), and forward to an active engagement with modernity. He challenged Muslims to shun superstition and stagnation, to revive the spirit of inquiry and reform that had once made their civilization great. And he showed by example how a faithful Muslim could simultaneously be a cosmopolitan modern person – conversant in Western thought, yet confidently rooted in Islamic identity. Asad’s life was a testament to the Qur’anic dictum: “God does not change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves” – implying that Muslims must take responsibility for their renewal. He worked tirelessly to provide the intellectual tools for that renewal, always insisting that faith and reason go hand in hand in Islam.

From Europe to Pakistan: A Visionary in the Muslim World

As Europe’s clouds darkened again in the 1930s, Muhammad Asad looked eastward – toward the Muslim lands – for his life’s purpose. He had by now spent years in Arabia (more on that soon), performed the Hajj to Mecca, and become an confidant of King Ibn Saud of newly-formed Saudi Arabia. But a new calling awaited: the idea of a separate homeland for Muslims in South Asia was gaining momentum, and Asad found himself drawn into that historic movement. At the personal request of Dr. Muhammad Iqbal, the famed poet-philosopher of British India, Asad traveled to the Indian subcontinent in 1932trtworld.com. Iqbal had read Asad’s writings and saw in him a rare European Muslim with the insight to help “elucidate the intellectual premises” of an Islamic statetribune.com.pk. In other words, Asad could articulate in English (and with Western intellectual rigor) what form a modern Muslim nation might take.

The Road to Pakistan’s Founding

Asad arrived in Lahore in 1932 with his wife (Munira, his third wife, whom he had married in Arabia) and their infant son Talaltrtworld.com. Stepping into the ferment of pre-independence India, Asad immediately became involved in various projects for Muslim educational and political revival. He lectured, wrote, and met with visionary leaders. In 1934, he published Islam at the Crossroads, a fiery little book that made waves across Indian Muslim circlestrtworld.com. In it, Asad unabashedly critiqued Western civilization’s spiritual emptiness while defending Islam and the Sunnah as the cure for global illstrtworld.com. He urged Muslims not to lose heart due to their colonized state: Materially, the West may be ascendant now, he argued, but do not be awestruck by its glamour. Take all beneficial knowledge (science, technology) from it, but leave its philosophy of life which is marred by secularism and moral relativismtrtworld.comtrtworld.com. “Only Islam can guide the world out of darkness,” he boldly asserted – words that electrified many educated Muslims searching for identitytrtworld.com. The book contextualized Europe’s historic hostility toward Islam (tracing it back to distorted impressions from the Crusades, etc.) and essentially told Muslims: be confident in your own faith, for it is closest to human nature and inherently justtribune.com.pk. Coming from a white European convert, these arguments carried extra weight. Muslim intellectuals like Iqbal and Maududi welcomed Asad’s voice, and even conservative ulema found little to object to in his strong advocacy of the Sunnah. Islam at the Crossroads thus established Asad as a prominent intellectual in South Asia’s Muslim communitytrtworld.com.

Over the next decade, Asad contributed to journals, plans for Islamic education reform, and the growing discourse on what an independent “Pakistan” (not yet realized) should embody. He worked on curricula to introduce modern sciences in madrasa education alongside classical subjectstrtworld.com. His idea was to prevent the dichotomy that had grown between “secular” and “religious” education – a gap he felt had harmed Muslims. All knowledge, after all, was from God, and a Muslim society should not sideline worldly sciences.

During these years, global events overtook him. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, British authorities became suspicious of Asad (an Austrian by origin). After Hitler annexed Austria, Asad was technically an “enemy national” in British India. Although he had no love for the Nazis – indeed, his own father and sister in Europe would later be murdered in the Holocausttrtworld.comtribune.com.pk – Asad was nonetheless interned by the British in 1939 as a wartime precautiontrtworld.com. He would spend most of the war (1939–1945) moving between internment camps in the subcontinent, enduring hardship and separation from his familytrtworld.comtrtworld.com. Tragically, he got news that his parents, unable to escape Europe, had been sent to Nazi concentration camps – a rare moment where Asad, usually stoic, broke down in tears (as his son Talal later recalled)trtworld.comtrtworld.com. The convergence of personal tragedy and global turmoil tested Asad’s faith, but did not break it. Upon release in 1945, he emerged with a renewed sense of mission for the impending birth of Pakistan.

Asad became an outspoken advocate that the future Pakistan should be founded on Islamic principles, not merely be a homeland for Muslims ethnically. He passionately joined the discourse on the Objectives and constitution of the new state. From 1947 onward (after Pakistan’s creation), Asad served in the Pakistan government in various capacities, where he tried to put his ideas into practice. Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan first appointed him head of the “Department of Islamic Reconstruction” – essentially a think-tank to align the new country’s policies with Islamic valuestrtworld.comtrtworld.com. In that role, Asad worked on proposals for Islamic social welfare, education, and economic justice. However, the political leadership soon decided Asad’s talents could be best used in diplomacy. With his polyglot tongue and cosmopolitan background, he was assigned to Pakistan’s Foreign Ministry, heading the Middle East divisiontrtworld.com.

A curious historical anecdote underscores Asad’s symbolic importance: When the time came for Asad to travel on behalf of Pakistan, he refused to use the standard travel document (which still labeled Pakistani officials as British subjects, since Pakistan had not yet finalized its citizenship laws)trtworld.com. Asad, proud of the new Muslim state, demanded a Pakistani passport – even though technically none yet existedtrtworld.com. After some confusion, the Prime Minister ordered that a special passport be issued to him. Thus, Muhammad Asad became holder of Pakistan’s Passport No. 1, effectively its first citizen in the symbolic sensetrtworld.comtribune.com.pk. This anecdote, often repeated, highlights how entwined Asad was with Pakistan’s nascent identity.

In the early 1950s, Asad’s diplomatic career peaked when he was sent as Pakistan’s Envoy to the United Nations. He took part in the General Assembly sessions in New York and was even elected as a chairman of one of the UN committees (a remarkable achievement for a newcomer nation’s representative)media.un.org. During these years in New York, Asad championed mutual understanding: he spoke about Islam’s message of peace at global forums, and helped establish Pakistan’s ties with other Muslim countries. One tangible outcome of his efforts – leveraging his old friendship with King Ibn Saud – was that Saudi Arabia warmly welcomed Pakistan, granting it diplomatic recognition and close cooperation early ontrtworld.com. A Pakistani historian noted: “He was the person who laid the foundation of our friendship with Saudi Arabia from which Pakistan is still benefiting. It’s sad that we have forgotten him.”trtworld.com.

Asad’s time in government, however, was not without controversy or personal turbulence. In 1952, while still at the UN, he married his fourth wife, Pola Hamida, a Polish-born convert to Islamtrtworld.com. This incident caused a mini-scandal back in Pakistan: the press, perhaps scandalized that a prominent figure had married a European woman (and possibly pricked by the fact that Asad’s prior wife Munira was left in Pakistan), indulged in unsavory gossip. Ridiculous rumors even circulated that Asad had “reverted to Judaism” – an irony given his steadfast commitment to Islamtrtworld.com. Munira, from whom Asad was estranged, agitated with government officials, accusing him of abandoning hertrtworld.com. Tired of the drama and under pressure, Asad resigned his position in 1952trtworld.com. It was a sad end to his official service, likely precipitated by interpersonal rather than ideological issues.

Despite these setbacks, Pakistan would continue to occasionally tap Asad’s expertise. In 1957, he was invited to organize a grand Islamic scholarly conference in Karachitrtworld.com. Asad used his formidable reputation and contacts across the Muslim world to bring dozens of scholars together, proving once more his ability to bridge cultures and languagestrtworld.com. Unfortunately, internal politics meant he didn’t get due credit (the published proceedings omitted his name)trtworld.com, deepening his disillusionment with Pakistani officialdom.

Fundamentally, Asad’s vision for Pakistan was that it should incarnate “Islam as an ideological proposition”, not just be a mirror of other nation-statestabletmag.comtabletmag.com. He wanted Pakistan to demonstrate how Islam could guide a modern, progressive society – a “laboratory” of Qur’anic principles applied to governance, law, and social justice. He strongly supported democracy within an Islamic frameworkmeforum.orgtrtworld.com. He argued against those who claimed dictatorship or monarchy was more “Islamic,” pointing out that the Qur’an and early Muslim practice emphasized shūrā (consultation) and accountability. In a newly independent Pakistan, where debates raged between secularists and Islamists, Asad tried to offer a middle path: a state rooted in Islamic values yet committed to pluralism and constitutionalism.

His influence on Pakistan’s early intellectual climate, while not always formally acknowledged, was significant. He is sometimes called “Europe’s gift to Islam” or to Pakistancriticalmuslim.com. Indeed, an article in a Pakistani journal noted wistfully that “there were many on the streets marching for the new country, but there were only a few like Asad who worked on the ideological front of Pakistan.”trtworld.com. That ideological front – figuring out how to translate Quranic ideals into public policy – was where Asad left an indelible mark. If Pakistan today has any identity as an “Islamic Republic” beyond just in name, it owes something to Asad’s foundational work.

After departing Pakistan’s service, Asad would never hold another government office. But he continued his mission through writing, translation, and personal example, which brings us to his literary legacy and later life.

Literary Legacy: Major Works and Writings

Muhammad Asad was not only a man of action and ideas but also a gifted writer with a flair for eloquent storytelling. Throughout his life, he produced a number of influential books that have inspired generations of readers – Muslims and non-Muslims alike. His writings range from autobiography and travelogue to exegesis and political theory. Below, we explore Asad’s major works, which collectively constitute his legacy in Islamic literature.

Read further in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment