Epigraph:

If there had been in the heavens or earth any gods but Him, both heavens and earth would be in ruins: God, Lord of the Throne, is far above the things they say. (Al Quran 21:22)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Belief in a single, all-powerful God (monotheism) lies at the heart of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the three Abrahamic faiths. This conviction not only shapes worship and morality, but also offers a unified way to understand reality itself. Monotheism asserts that one divine intelligence underpins all of existence, providing an overarching coherence to the universe. By contrast, polytheism (belief in many gods) and atheism (belief in no god) propose very different pictures of reality. In this article, we will explore how the belief in One God makes the universe coherent from three perspectives: philosophical, theological, and scientific. We will see how monotheism supplies a unified explanation of existence, how the sacred texts of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam proclaim divine unity, and how the order of the cosmos and its laws can be viewed as reflections of a singular Creator.

Philosophical Perspective: A Unified Explanation of Existence

From a philosophical standpoint, monotheism provides a clear and unified explanation for why anything exists at all. If there is only one ultimate Creator responsible for everything, then all aspects of reality trace back to a single source, giving reality an inherent unity. Philosophers have long noted the appeal of invoking one cause rather than many: ancient thinkers in the Greco-Roman world began to prefer a single divine principle as more “economical” and coherent than multiple gods. As one scholar observes, early philosophers “valued the idea of a single cause over many causes”, seeking to eliminate the capricious whims of many deities in favor of one rational principle guiding all things. In a world governed by one supreme Being, the laws of nature, the existence of life, and the moral order can all be seen as parts of a consistent divine plan, rather than unrelated outputs of competing powers.

Monotheism vs. Polytheism vs. Atheism: In terms of explanatory power, monotheism offers an ultimate answer that both polytheism and atheism struggle to provide. Polytheistic systems, with many gods in charge of different domains, risk a fragmented view of reality – the gods might conflict with each other, leading to an incoherent universe. Indeed, the Qur’an makes a philosophical point in this regard: “Had there been any gods in the heavens and the earth apart from Allah, the order of both the heavens and the earth would have gone to ruins.”

In other words, multiple gods pulling the strings would result in cosmic chaos, not the orderly cosmos we observe. Atheism, on the other hand, denies any intentional cause behind existence – the universe has no creator or ultimate reason for being. While atheists can certainly describe how the universe operates, they leave unanswered the classic question of why there is an orderly universe at all. By positing one intelligent Creator as the source of matter, energy, law, and even reason itself, monotheism fills this explanatory gap: everything exists because a rational God willed it to be. This aligns with the philosophical principle of sufficient reason (explored by thinkers like Leibniz), which suggests that there must be an ultimate explanation for the existence of the universe – monotheists identify that explanation with God.

Classical Arguments for One God

Over centuries, philosophers and theologians have developed classic arguments for the existence of one God that highlight the coherence of a monotheistic worldview. Three of the most prominent are the cosmological, teleological, and moral arguments:

- Cosmological Argument (First Cause): This argument begins from the existence of the universe and contends there must be a first cause or necessary being that explains why anything exists. One formulation (the Kalam cosmological argument) states: “Whatever begins to exist has a cause. The universe began to exist. Therefore, the universe had a cause.” Monotheists identify this uncaused first cause with God – a singular, eternal creator who sparked reality into being. As St. Thomas Aquinas argued in his Five Ways, the chain of causes in nature cannot regress infinitely; there must be an unmoved mover or first cause that itself was not caused by anything else. Monotheism neatly satisfies this by providing one uncreated Creator at the origin of everything.

- Teleological Argument (Design): This is the classic “argument from design,” which observes purpose, order, and complexity in the world and infers an intelligent designer. The natural world exhibits intricate structures – from the laws of physics to the information in DNA – that appear finely tuned for life. The teleological argument holds that such “complex functionality in the natural world, which looks designed, is evidence of an intelligent creator.” Just as the precise gears of a watch imply a watchmaker, the precise constants and conditions of the universe imply a cosmic Designer. This idea has been noted since at least ancient Greece and was later advanced by medieval thinkers of all three Abrahamic faiths (for example, the Muslim theologian Al-Ghazali and the Christian philosopher Aquinas both used design arguments). A modern example of fine-tuning: the electromagnetic force constant is approximately 1/137 – if it were only a few percent different, stars would not produce carbon or might not form at all, making life impossible. Nobel laureate physicist Richard Feynman marveled at this “mystery of 1/137,” remarking “You might say the hand of God wrote that number and we don’t know how He pushed His pencil.” Such observations strengthen the teleological case that one intelligent God set the “dials” of the cosmos just right for a coherent, life-supporting universe.

- Moral Argument (Lawgiver): Human beings across cultures have a sense of moral law – a perception of right and wrong that often converges on core principles (like justice, honesty, compassion). The moral argument posits that if an objective moral law exists, there must be a transcendent moral Lawgiver who grounds these values. Monotheism provides this grounding by asserting a perfectly good God who imbued the universe (and human conscience) with moral order. C.S. Lewis famously presented this reasoning: noticing that people quarrel by appealing to a shared standard of behavior, he argued that there must be a real Moral Law above individual whims – and thus a Source of moral law. In a polytheistic setting, by contrast, moral duties could become confusing – if one god demanded X and another demanded Y, which prevails? And in an atheistic frame, moral norms might be seen as mere human preferences or evolutionary byproducts, not binding truths. Monotheism’s single divine lawgiver offers a coherent basis for ethics: one God, one moral standard. As a result, it “often leads to a unified moral and theological framework, where all people are subject to the will of one God,” rather than a chaos of competing duties.

In summary, philosophically, the hypothesis of one God simplifies and solidifies our explanation of reality. It avoids the internal contradictions of polytheism (no fights among gods if there’s only one God) and provides an ultimate reason that atheism lacks (the universe is orderly because a rational Creator made it so). This is not to claim these arguments are without debate – philosophers continue to discuss and refine them – but each shows how monotheism, as a worldview, strives for a comprehensive, unified account of existence that resonates with our observations of causality, design, and moral truth.

Theological Perspective: Divine Unity in the Abrahamic Faiths

In the lived traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the unity of God is a bedrock tenet that shapes all other beliefs. Each of these religions, while distinct in many ways, emphatically teaches that there is only one true God who is the Creator and Sustainer of everything. This core concept of divine unity (often called monotheism or oneness of God) is richly attested in their holy scriptures and carries profound implications for how believers view morality, purpose, and human destiny.

Judaism: “The LORD is One”

In Judaism, God’s oneness is uncompromising. The central creed of the Jewish faith is the Shema, named after the Hebrew word for “hear,” which declares: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is One.” (Deuteronomy 6:4). This ancient confession, recited daily by observant Jews, affirms that YHWH (the God of Israel) alone is truly God. It was a bold statement in the context of the polytheistic Near East, setting Israel apart from neighbors who worshipped multiple gods. As one commentary notes, “This declaration is a profound statement of monotheism, affirming that Yahweh is the sole, indivisible God… It emphasizes God’s uniqueness and unity, rejecting any division or multiplicity of deities.”

Jewish scripture repeatedly stresses that no other gods exist: “I am the First and I am the Last; besides Me there is no God,” says God in Isaiah. The First Commandment given at Sinai likewise prohibits worship of any but the one true God. Thus, the theological worldview of the Hebrew Bible is one of radical divine unity – all power, all creation, and all authority belong ultimately to a single, sovereign God.

This strong monotheism in Judaism not only explains why the universe exists (it’s created by God), but also unifies morality and purpose. Because there is only one God, the moral laws He gives (such as the Ten Commandments) are universal and binding – there is no other divine will to contradict them. History and nature, too, are seen as a coherent story authored by one God rather than a patchwork of competing divine agendas. The result is a worldview in which everything is interconnected under one ultimate authority.

Christianity: One God in Three Persons

Christianity inherited the Jewish affirmation of one God and carried it into the Greco-Roman world. In the New Testament, Jesus himself quotes the Shema, confirming the oneness of God: “The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Mark 12:29). Early Christians, all of whom were Jewish or influenced by Judaism, firmly rejected polytheism – for them, the God of Israel was the only God. The Apostle Paul wrote, “We know that ‘an idol is nothing at all in the world’ and that ‘there is no God but one’” (1 Corinthians 8:4), and “there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things… and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things” (1 Corinthians 8:6). Such statements underscore that the Christian view of reality is anchored in the oneness of the Creator.

Christian theology does introduce a unique understanding: the doctrine of the Trinity, which holds that the one God exists as three co-eternal “Persons” (Father, Son, Holy Spirit). At first glance, this might seem to challenge divine unity, but Christian doctrine insists it does not – the three Persons are not three gods, but one God in essence. The Nicene Creed begins, “We believe in one God.” The Trinity is seen as a unity in diversity, a mystery of one divine being in a triune life. While philosophically complex, this doctrine still affirms monotheism: all of reality is governed by one supreme Being. The coherence here is subtler: Christians see relational love within God’s one being (Father, Son, Spirit in eternal relationship), which they believe makes sense of love and community in creation. Importantly, for our purposes, Christianity no less than Judaism asserts that only one God created the universe and sustains it. There is no division of divine power; even the devil in Christian thought is not an independent god of evil, but a rebel creature under God’s ultimate sovereignty. Thus, the Christian universe remains a unified kingdom under one King, and the moral order (summarized as “Love God and love your neighbor”) stems from that one God’s character and commandments.

Islam: Tawhid – God’s Absolute Oneness

Islam is, if possible, even more explicit and emphatic about the oneness of God. The very first pillar of Islam, the Shahada (testimony of faith), declares: “La ilaha illallah” – “There is no god but God (Allah).” This concept of Tawhid (Arabic for “unity” or “oneness”) permeates the entire Qur’an. Muslims believe Allah is utterly one – singular in essence, with no partner, no division, and no equal. The Qur’an rejects any notion of multiple gods or God having associates, and frequently polemicizes against the polytheism of Mecca’s pagan Arabs or the Christian idea of Trinity (which the Qur’an misunderstood as “three gods”). One short Qur’anic chapter, Al-Ikhlas (112:1-4), is devoted to God’s oneness: “He is Allah, the One; Allah, the Eternal. He neither begets nor is born, nor is there any equivalent to Him.” Another verse states, “Your God is One God; there is no god but Him, the All-Merciful, the Compassionate.” (Qur’an 2:163).

Islamic theology not only asserts one God, but also draws a direct line from the order in creation to the unity of the Creator. Muslim scholars have noted that the seamless “homogeneous, well-knit and unique system of the world” is itself “a proof of the Unity of its Creator.” The Qur’an encourages believers to reflect on how all of nature works in harmony – the alternation of night and day, the movement of ships at sea, the rain reviving the earth – as signs that “it has been designed and is being managed by One Supreme Being.”

In Islamic thought, it is not only blasphemous but also irrational to suppose multiple gods; the coherence of natural law points to one Lawmaker. The Qur’an even presents a succinct philosophical argument: “Had there been within the heavens and earth gods besides Allah, they both would have been ruined” – in other words, the stability of the cosmos testifies to the oneness of its ruler.

For Muslims, Allah’s oneness also means that worship and morality must be unified. All worship is due to God alone (shirk, or associating partners with God, is the greatest sin in Islam). Likewise, all humans are judged by the same divine standard of righteousness. There is a strong sense of universal brotherhood under the one Creator – the Qur’an teaches that all peoples were created by the one God and thus are part of one human family, differing only in their consciousness of Him. In summary, Islam propounds a worldview where everything finds unity in God: the physical universe, the purpose of life (to worship God), and the standard of good (the will of God) are all tied together by the fact that “He alone is the Creator, He alone manages the world.”

Unity of God and the Implications for Morality & Purpose

Belief in one God profoundly influences how the Abrahamic faiths understand morality, meaning, and human existence. If there is a single Creator who made all people in His image (as Judaism and Christianity teach) or for His service (as Islam teaches), then there is an inherent dignity and purpose to human life. Morality is not a human invention nor a set of arbitrary rules, but the expression of one God’s character and commands, meant for the wellbeing of His creation. Right and wrong have an objective foundation because the one God is the ultimate lawgiver for all humanity. In practical terms, this means that concepts of justice, mercy, honesty, and love are grounded in God’s own nature and His revelations (whether the Torah’s laws, Jesus’s teachings, or the Shariah in Islam). A polytheistic framework, by contrast, often lacks a single moral axis – duties might conflict (one god demands war, another demands peace), and the question arises “which god’s morality do we follow?” The unified God of monotheism solves this by providing one moral compass that applies universally. For example, when Israel’s prophets preached ethics, they appealed to one Yahweh who is righteous and makes ethical demands (e.g. “What does the LORD require of you?” in Micah 6:8). Similarly, in Islam, Allah’s oneness undergirds the concept of a single ummah (community) with a universal law (the Sharīʿah) for right conduct.

Purpose and meaning in life are also clarified by monotheism. If one loving God created us intentionally, our lives are not accidents; they have purpose. We exist to know, love, and serve God, and to fulfill the unique roles He has given us in the cosmic story. This conviction can provide a powerful sense of hope and direction. Former Chief Rabbi of Britain Jonathan Sacks explained that “Monotheism, by discovering the transcendent God… made it possible for the first time to believe that life has a meaning, not just a mythic or scientific explanation.”

In other words, life is not mere fate or random chance; there is a narrative endowed by the Creator that redeems human existence from meaninglessness. Rabbi Sacks further noted, “Monotheism, by giving life a meaning, redeemed it from tragedy… It is the principled defeat of tragedy in the name of hope.”

In polytheistic ancient cultures, people often saw themselves at the mercy of capricious gods and blind fate – hence the pervasive sense of tragedy in Greek literature. But Abrahamic monotheism brought a new sense of hope: since one sovereign God is in control, even suffering can have a purpose in His plan, and justice will ultimately be served (e.g. Judgment Day, messianic age, etc.). Likewise, in Christianity, the belief in one God who became incarnate in Christ to save humanity imparts enormous value to each person’s life and offers hope of eternal life. In Islam, the belief in one just and merciful God assures that nothing we do is unseen and that ultimate justice will be done in the hereafter, giving meaning to moral striving.

In summary, the theological perspective shows that divine unity is not an abstract dogma – it is the key that unlocks a coherent vision of life. One God means one human family under one authority, one moral law binding all, and one ultimate purpose for creation. The adherents of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam find comfort and coherence in knowing that the same God who “alone made the heavens and earth” also guides their daily lives and destinies. The universe, in their view, is not a hopeless maze; it is a cosmos – an ordered whole – ruled by a singular Divine King.

Scientific Perspective: Order, Fine-Tuning, and the “Mind of God” in the Cosmos

Science, at its core, seeks to understand the order of the universe – and the remarkable success of this endeavor has often been linked to the assumption (and reality) that nature is ordered in a consistent, unified way. The monotheistic idea of a singular divine Creator complements this by positing a rational Mind behind the cosmos, whose design makes the universe intelligible. Historically, many scientists (including devout followers of the Abrahamic faiths) were inspired by the belief that since one God established the laws of nature, those laws should be coherent, discoverable, and uniform everywhere. Modern scientific findings about the fine-tuning of the universe have further intrigued philosophers and theologians, as they seem to align with the expectation that a single Creator set the conditions for life. Let us examine how the order and precision we observe scientifically can be seen as reflections of divine unity.

The Intelligible Order of the Universe

One striking fact about our universe is that it makes sense – it operates by regular laws (like gravity, electromagnetism, conservation of energy) that we can describe with mathematics. If reality were complete chaos, science would be impossible. Instead, scientists find that “the universe has a recognizable order, pattern, and sequence”, displaying structure at all levels. Apples reliably fall down, not up; planets orbit predictably; chemical reactions follow precise rules. These patterns hold true across the cosmos and across time. As physicist (and Anglican priest) John Polkinghorne noted, the remarkable thing is not just that the universe exists, but that it is rationally transparent to us – it follows laws that our minds can grasp. Monotheists see this profound orderliness as no coincidence: a rational God crafted a rational universe, and He made our minds with the capacity to understand His handiwork (since, as Genesis says, we are made in God’s image, including our reasoning ability).

In fact, the success of science historically depended on the assumption of a single orderly author of nature. Many historians have pointed out that the scientific revolution bloomed in monotheistic (largely Christian) cultures because the belief in one Lawgiver encouraged the search for universal laws in nature. Sir Isaac Newton, a devout (if unorthodox) Christian, famously expressed his awe at the solar system’s harmony as evidence of divine design: “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets, and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being.”

Newton even argued that if other stars have planets, “these, being formed by the like wise counsel, must be all subject to the dominion of One.”

In other words, one God rules all planetary systems by the same physics. Albert Einstein, who rejected a personal God but still described himself as “religious” in a cosmic sense, spoke of “Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists.”

He was struck by how comprehensible the universe is, calling it “the most incomprehensible thing about the universe… that it is comprehensible!” Here we see a convergence: whether one is a believer like Newton or a more pantheistic thinker like Einstein, the perception that a single kind of order pervades nature is clear. This unity of natural law points back to a unified source. Philosopher Alvin Plantinga makes the point succinctly: “For science to be successful, the world must display a high degree of regularity and predictability… The world was created in such a way that it displays order and regularity; it isn’t unpredictable, chancy or random.”

The monotheistic interpretation is that God’s singular will imposes that regularity on all of nature, which is why experiments here on Earth hold true under the same conditions on Mars or in distant galaxies.

It’s worth noting that atheism also expects order (since otherwise there could be no stable science), but it must treat the universe’s order as a happy brute fact. The theist can say the universe is ordered because an Orderer made it so – a purposeful explanation – whereas the atheist might say “that’s just how things happened to be.” Thus, when we find that mathematics beautifully describes physical reality, monotheists like physicist Paul Dirac speak in almost reverent terms: “God used beautiful mathematics in creating the world.” Even secular scientists often use language like “the mind of God” as a metaphor for the elegant laws of nature. All this scientific harmony resonates strongly with the idea of one rational Creator.

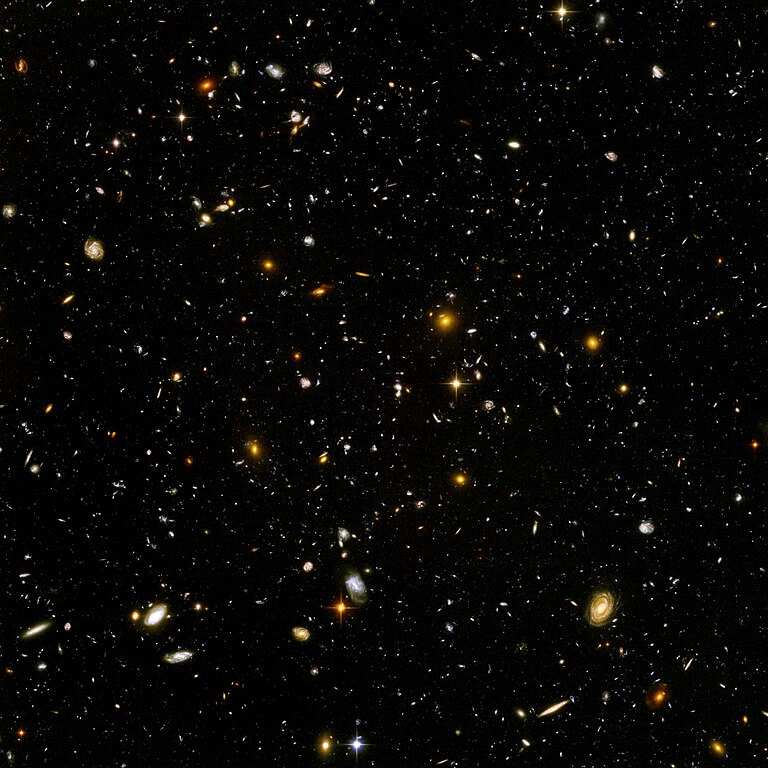

Fine-Tuning and the Anthropic Principle

Beyond general laws, scientists have discovered that the fundamental constants and initial conditions of the universe are astonishingly well-suited for the existence of life. This is known as the fine-tuning of the universe. Dozens of parameters – from the strength of gravity to the charge of the electron, from the mass of a proton to the rate of cosmic expansion – fall within narrow ranges that allow complex structures (stars, planets, carbon chemistry, and ultimately living organisms) to exist. If any of these numbers were tweaked even slightly, the universe might be lifeless. For example, if the strong nuclear force (which holds atomic nuclei together) were a few percentage points weaker or stronger, stable atoms essential for biology would not form. As one summary explains, “the masses of subatomic particles, the strengths of atomic forces, and the nature of space and time have values that allow for the existence of matter, stars, galaxies and planets hospitable to the formation of life.”

These values appear finely balanced; in fact, “many scientists have noted that the values of these key constants appear to be arbitrary and possibly random, making the probability of a universe like ours vanishingly small.”

Physicist Fred Hoyle, after discovering the finely-tuned resonance that produces carbon inside stars, remarked that it was as if “a super-intellect has monkeyed with physics” to make life possible. Such observations naturally raise the question: why is the universe so finely tuned?

For those who believe in one God, the answer is straightforward: the same God who desired life and persons to exist set the constants appropriately. Fine-tuning is seen as the intentional work of a benevolent Creator who fashioned a universe capable of eventually producing creatures like us. The remarkable precision is not a coincidence but a signature. As modern philosopher Richard Swinburne has argued, it would be incredibly unlikely for all these parameters to fall in place by chance, whereas it’s not surprising if a Creator chose them. In fact, “philosophers and theologians such as Richard Swinburne and Robin Collins have argued that fine tuning must imply that there was a fine-tuner”, contending that an intelligent mind behind the cosmos is the best explanation. This dovetails with the classical teleological argument we discussed earlier, now bolstered by astrophysics and cosmology.

Some scientists propose alternative explanations like the anthropic principle or a multiverse to avoid the implication of a designer. The anthropic principle, in its weak form, basically states: “We shouldn’t be surprised the universe’s constants allow life, because if they didn’t, we wouldn’t be here to notice – out of necessity, we observe a life-permitting universe.”

This is true as far as it goes (it’s a selection effect), but it doesn’t actually explain how the constants got their values; it just says any observers will only see a hospitable universe. The strong anthropic principle takes it a step further, almost suggesting the universe had to have these life-permitting values (which drifts toward a philosophical or teleological claim itself). Another popular idea is the multiverse hypothesis: maybe our universe is just one of an enormous ensemble of universes with varied constants, and we, unsurprisingly, find ourselves in the rare universe that by chance has the “Goldilocks” conditions for life. If there are countless universes, the improbability of fine-tuning can be diluted. However, as a scientific idea, the multiverse is speculative – by definition, other universes (if they exist) are not observable, so the theory is hard to test or confirm. Some have pointed out that invoking a multiverse is not much different from invoking God – both are explanations beyond the one universe we see, and neither can be directly observed; one is a purposeful agent, the other a purposeless ensemble. Ultimately, which explanation one finds more plausible may depend on philosophical temperament. But it’s noteworthy that the order and precision of the cosmos have led many scientists to theological reflection rather than away from it. As astrophysicist Luke Barnes (who studies fine-tuning) said, theism provides a neat explanation: a single Creator wanted a life-permitting universe and thus fine-tuned it accordingly.

Unity in Diversity: Scientists Who Saw God in the Details

Throughout history, a number of leading scientists in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic world have explicitly linked their scientific discoveries to belief in a unified divine order. Their reflections provide anecdotal evidence that monotheistic faith can reinforce the sense of cosmic coherence:

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727): After formulating the laws of motion and universal gravitation, Newton famously wrote in his Principia Mathematica that the elegant system of the heavens could only arise from the design of one mighty Creator. He asserted that the orderly orbits and regularity of planetary motions “could by no means have at first derived the regular position of the orbits themselves from those laws [of physics].… This most beautiful system… could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being.” Newton even suggested that the stars, if they host their own systems, must all be under “the dominion of One.” He saw his science as revealing the consistency of God’s workmanship. For Newton, God’s unity guaranteed the universality of natural laws (the apple falls and the moon orbits by the same gravity), a principle we take for granted now.

- Albert Einstein (1879–1955): Einstein’s belief in God was unconventional – he rejected a personal God, aligning more with Spinoza’s view of God as the logical structure of nature – but he often spoke in awe of the harmony of the cosmos. He is quoted saying, “I’m not an atheist… I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists.” He also referred to an inscrutable intelligence revealed in the laws of the universe, sometimes using the term “Old One” to denote God in a metaphorical sense (as in, “God does not play dice,” his objection to pure randomness in quantum mechanics). Einstein’s perspective underscores that even without adhering to organized religion, the concept of one underlying order (which one might poetically call “God”) is deeply compelling. It is the unity of physical law – the fact that the same electromagnetism governs both a star and an atom – that Einstein found wondrous. In his view, the coherency of the world was “miraculous” and deserved a quasi-religious reverence.

- Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1040): A pioneering Muslim scientist of the medieval age, Ibn al-Haytham is often credited with developing early scientific methods and making breakthroughs in optics. He was also a devout believer in Allah’s oneness, and his faith directly fueled his science. He held that seeking knowledge was a way of getting closer to God: “I constantly sought knowledge and truth, and it became my belief that for gaining access to the effulgence and closeness to God, there is no better way than that of searching for truth and knowledge.”For Ibn al-Haytham, studying nature was like reading a book authored by God – since Allah is Al-Sani’ (the Maker), the sole creator, by examining creation one could appreciate the “consummate perfection of His work.”He explicitly wrote that “Allah is the sole Creator. Everything else, including man and the natural environment that man studies scientifically, are simply creations.” This theological view led him to look for the rational, unified principles by which God structured the world. In his study of the eye, for instance, he remarked on “the wisdom of the Maker… and the skillfulness of His work” in its design. Thus, one of the founders of the scientific method saw no conflict between science and faith – rather, his belief in one God’s “wise disposition of the world” drove him to investigate how that world functioned. Many other great scientists in history, from Johannes Kepler (“thinking God’s thoughts after Him”) to James Clerk Maxwell (who famously included biblical mottoes on his equations), have likewise felt that their discoveries unveiled a bit of the divine plan — a plan unified because its Planner is one.

In the modern era, the dialogue between science and monotheism continues in a respectful exchange. Not all scientists are religious, of course, and not all believers feel the need to see scientific fine-tuning as proof of God. But the alignment between a universe that behaves as a unified whole and the idea of one universal Creator is a fascinating convergence. It suggests that the religious intuition of an underlying One and the scientific quest for a Theory of Everything are, in a sense, both seeking a final unity. As a contemporary astrophysicist (and priest) Rev. George Coyne put it, “Science is possible only because the universe is truly rational in its origin,” hinting that science itself is grounded in the gift of order from a single Source.

Conclusion: One God, One Coherent Reality

Belief in one God has been a powerful unifying idea, one that threads together our understanding of existence from the abstract heights of philosophy to the daily practice of ethics and the empirical study of nature. We have seen that:

- Philosophically, monotheism offers a coherent framework in which everything that is has a single ultimate explanation or purpose. It brings simplicity (one cause, not many) and resolves the question of “why is there something rather than nothing” by pointing to a necessary being. It also undergirds objective values by positing one supreme Good. Compared to polytheistic or atheistic worldviews, it avoids internal contradictions and infinite regresses by providing a final unifying answer – God – to the puzzle of reality.

- Theologically, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all proclaim the unity of God as the cornerstone of truth. Their scriptures and teachings insist that the universe is the purposeful creation of one deity, not the battleground of many or the product of none. This belief yields a unified moral law and a universal human family, giving believers a strong sense of meaning and hope. The problems of life – suffering, injustice, death – are approached with the trust that a single loving God holds the answers, even if presently unseen. In each tradition, the unity of God also means the unity of truth: religious truth and scientific truth cannot ultimately conflict, since all truth flows from the same divine source.

- Scientifically, the presumption of an orderly, unified cosmos has been validated over and over. The laws of physics apply everywhere, suggesting one Lawgiver. The fundamental constants are finely balanced, suggesting one fine-tuner. And the human mind can grasp cosmic truths, suggesting a kinship between the rationality within us and the rationality “out there” – a kinship a believer might credit to the imago Dei (image of God) in which we were created. Far from being at odds with science, monotheism historically nurtured it, and today many find that it elegantly explains why science is even possible: because a rational God made a rational universe. The sense of wonder that scientists feel when uncovering the universe’s secrets often echoes the religious awe of contemplating God’s creation.

In closing, the coherence that monotheism lends to the universe does not prove the existence of God – that remains a matter of faith, supported by reason. But it does mean that those who believe in one God find themselves at home in a universe that is orderly and meaningful. There is a remarkable synergy between the idea that “in the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” and the testimony of nature that everything in the heavens and the earth follows the same elegant principles. It’s as if reality carries a watermark of unity. Monotheism provides a lens through which the vast diversity of existence – from quarks to galaxies, from music to mathematics, from love to logic – comes into focus as the expression of one foundational Reality. In the words of a famous dictum: “All truth is God’s truth.” By believing in One God, millions have found that everything else falls into a coherent place. The universe, in all its richness, tells a single story – the story authored by the One.

Sources:

- Scriptural monotheism in Judaism and Christianity – Deuteronomy 6:4 commentary; Isaiah 44:6; Gospel of Mark 12:29 referencing the Shema.

- Qur’anic monotheism and coherence – Qur’an 21:22 (multiple gods would ruin heaven & earth) myislam.org; Philosophy of Islam on Allah’s unity as sole Creator sibtayn.comsibtayn.com.

- Philosophers on single cause vs many – Greek move to monotheism for “economy and coherence” vridar.org. Classical arguments: Kalam cosmological argument en.wikipedia.org; Teleological argument definition en.wikipedia.org; C.S. Lewis’s moral argument en.wikipedia.org.

- Moral framework: Monotheism yields unified moral law studocu.com.

- Rabbi Sacks on monotheism and meaning rabbisacks.orgrabbisacks.org.

- Scientific order: description of cosmic order enabling science summit.orgsummit.org; Plantinga quote on created orderliness summit.org.

- Newton on God’s design in Principia inters.org. Einstein quote on Spinoza’s God and harmony en.wikipedia.org.

- Ibn al-Haytham on seeking truth to get closer to God en.wikiquote.org and Allah as al-Sani’ (Maker) the sole Creator islamicity.org.

- Fine-tuning facts: electromagnetic constant and “hand of God” (Feynman) bobblum.com; overview of fine-tuning and design argument by Swinburne/Collins templeton.orgtempleton.org.

- Anthropic principle explained templeton.org.

Leave a reply to What’s the New Atheism and How to Refute It? – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply