Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Fasting as a biological and spiritual shield

Abstract

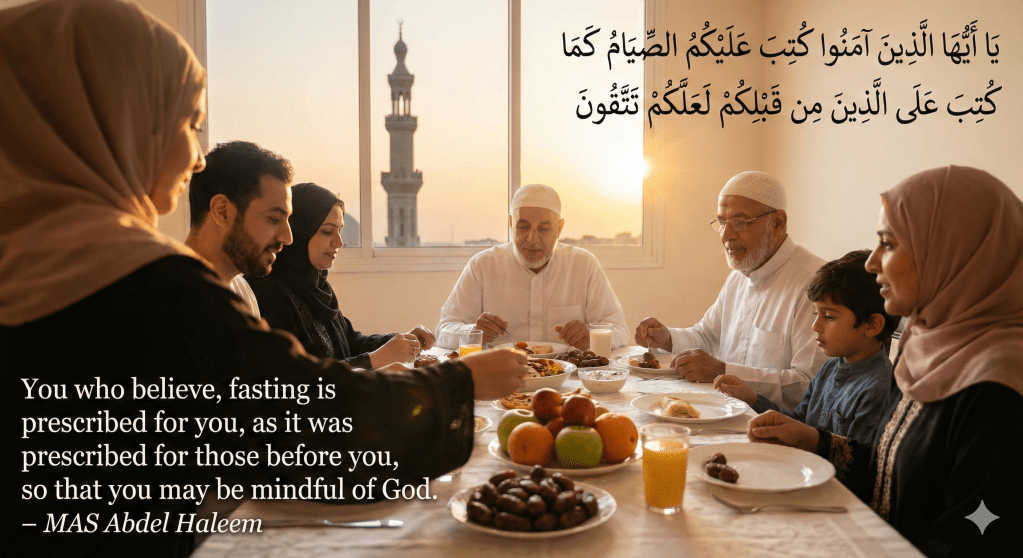

This report presents an exhaustive multidisciplinary analysis of Surah Al-Baqarah, verse 183, which serves as the foundational legal and spiritual decree for fasting in Islam. By synthesizing historical, philosophical, and theological perspectives, the study elucidates how the command of Sawm (fasting) transcends mere ritual to become a mechanism for comprehensive human refinement. Historically, the verse is situated within the Medinan period, marking a significant transition from earlier Semitic fasts, such as the Ashura observance, to the institutionalized month of Ramadan. Philologically, the analysis investigates the profound implications of terms such as Kutiba (prescribed) and Taqwa (God-consciousness), framing the latter as a protective shield for the soul. A central component of this report is the incorporation of contemporary arguments by Dr. Zia H. Shah, which posit that the verse’s assertion of fasting as a universal religious practice constitutes a verifiable proof of the Quran’s divine origin. Through an examination of global indigenous fasting traditions—from the “Vision Quests” of Native Americans to the initiation rites of Australian Aboriginals—the study demonstrates how the Quranic claim of universal prescription, made in 7th-century Arabia, anticipated later anthropological discoveries. Furthermore, the report explores the biological and psychological intersections of fasting, including the mechanism of autophagy and the science of self-regulation, as material manifestations of the spiritual “signs” (ayat) promised in the text. The analysis culminates in a thematic epilogue on the role of fasting as a bridge between human biology and spiritual transcendence.

Linguistic Foundations and Philological Analysis

The inquiry into Quran 2:183 begins with a meticulous examination of its linguistic structure, as the Arabic text provides the primary framework for its legal and spiritual interpretation. The verse opens with the vocative particle Ya ayyuha, a call directed specifically at the believers (allatheena amanoo), which serves to soften the forthcoming obligation through a reminder of the intimate bond between the Creator and the created.

The Force of the Decree: Kutiba

The predicate of the verse, Kutiba, is a passive verb meaning “it has been written” or “it has been prescribed”. In Quranic jurisprudence, the use of Kutiba denotes a binding divine decree, placing fasting on the same level of legal necessity as the laws of inheritance (al-wasiyyah) and the law of retribution (qisas). This linguistic choice signifies that the fast is not an optional spiritual exercise but an essential component of the human design, etched into the metaphysical ledger as a requirement for spiritual health. The passive voice suppresses the agent (Allah) to focus on the act of prescription itself, highlighting the universality and timelessness of the command.

Defining the Act: As-Siyam and As-Sawm

The term used for fasting, As-Siyam, is derived from the root ṣ−w−m, which literally means “to abstain,” “to desist,” or “to be still”. Historically, the root was applied to horses that refrained from neighing or eating, and to the sun when it appeared to stand still at its zenith. In the legal context of Islam, As-Siyam refers to the voluntary abstention from food, drink, and sexual intimacy from the break of dawn (fajr) until sunset (maghrib), performed with a specific intention (niyyah). Scholars differentiate between the general state of abstinence (sawm) and the specific ritualized fasting (siyam), with the latter implying a structured, collective discipline that purifies the soul from base desires.

The Teleological Goal: Taqwa

The verse concludes with the purpose of the fast: la’allakum tattaquun (“so that you may attain Taqwa”). While commonly translated as “piety” or “God-fearing,” the term Taqwa originates from the root w−q−y, meaning “to protect,” “to guard,” or “to shield”. Therefore, Taqwa is the state of building a “wiqayah” (protection) between the self and the displeasure of God. Unlike khawf (fear), which implies a flight from a perceived threat, Taqwa implies an internal vigilance and self-restraint that enables a person to ward off evil. In this sense, fasting is presented as a “spiritual technology” designed to construct an internal defense system against the impulses of the lower self (nafs).

| Terminology | Root | Primary Meaning | Application in 2:183 |

| Kutiba | k−t−b | To write / prescribe | Establishes fasting as a binding divine law. |

| As-Siyam | ṣ−w−m | To abstain / desist | The ritualized act of refraining from physical appetites. |

| Taqwa | w−q−y | To shield / protect | The ultimate goal: a protective state of God-consciousness. |

| Al-Allatheena Amano | a−m−n | Those who believe | The target audience: individuals committed to faith. |

Historical Evolution and the Medinan Context

The revelation of Quran 2:183 represents a pivotal moment in the development of the Islamic community after the migration (Hijrah) to Medina in 622 CE. During the initial years in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad and the Muslims were establishing a new social order that integrated spiritual practice with legal and social governance.

The Transition from Ashura to Ramadan

Before the formal legislation of the Ramadan fast in 2 A.H. (624 CE), the Muslims observed the fast of Ashura on the 10th of Muharram. This practice was adopted after the Prophet observed the Jewish tribes in Medina fasting to commemorate the day Moses and the Israelites were saved from Pharaoh. The Prophet declared that Muslims had a greater claim to Moses and thus commanded the fast of Ashura. However, once verse 2:183 was revealed, the month-long fast of Ramadan became the primary obligation, while the Ashura fast was relegated to an optional, supererogatory status.

The Philosophy of Gradualism

Islamic law regarding fasting followed a principle of gradualism to ensure the community could adapt to the rigorous requirement.

- Phase I: Fasting was initially limited to three days per month and the day of Ashura.

- Phase II: The revelation of 2:183 introduced the obligation of Ramadan but provided a choice (takhyir). Those who were healthy but found the fast difficult could opt to feed a needy person (fidya) instead of fasting.

- Phase III: The subsequent revelation of verse 2:185 removed this choice for able-bodied, non-traveling Muslims, making the fast mandatory while maintaining exemptions for the sick and travelers.

This transition reflects the Quranic ethos of balancing “hardship” and “ease.” As stated in verse 2:185, “Allah intends for you ease and does not intend for you hardship”. The historical evolution of the fast demonstrates a pedagogical approach where the community was progressively trained in self-discipline until they reached a level of spiritual maturity capable of sustaining a month of continuous abstinence.

Comparative Theology: Fasting as a Universal Heritage

A unique feature of Quran 2:183 is the clause kama kutiba ‘ala allatheena min qablikum (“as it was prescribed for those before you”). This statement serves both a psychological and a theological purpose. Psychologically, it offers “comfort in numbers,” reminding the believers that the challenges of fasting have been borne by all previous religious communities. Theologically, it asserts the continuity of the divine message and the unity of the prophetic tradition.

Fasting in Judaism and Christianity

The Quranic reference to “those before you” primarily includes the People of the Book (Ahl al-Kitab). In Judaism, fasting is a central mechanism for atonement (teshuvah) and mourning. The fast of Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) mirrors the Islamic fast in its rigors, requiring 25 hours of total abstinence from food, drink, and marital relations. Judaism teaches that fasting creates an “empty space” in the body, making room for spiritual connection and fostering empathy for the hungry.

In Christianity, fasting is modeled after the forty-day fast of Jesus in the wilderness. While the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic traditions have maintained various forms of fasting (such as Lent), the Protestant tradition often views fasting as an optional act of devotion. Despite differences in timing and dietary restrictions (e.g., abstaining from meat but not water), the underlying purpose of Christian fasting remains the cultivation of humility and penance.

Fasting in Eastern and Ancient Religions

The universality of fasting extends beyond the Abrahamic sphere into Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Hinduism incorporates fasting (Vrata) into its lunar calendar, such as the Ekadashi fast (observed on the eleventh day of the lunar fortnight). Jainism represents one of the most rigorous fasting traditions, viewing abstinence as a means of non-violence (ahimsa) and karmic purification. Buddhism encourages monastic fasting, where monks refrain from eating after noon to maintain a state of “mindfulness” and alertness.

| Religion | Primary Fasting Event/Method | Objective |

| Judaism | Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) | Atonement, mourning, and repentance. |

| Christianity | Lent (40 days leading to Easter) | Penance, preparation, and humility. |

| Hinduism | Vrata / Ekadashi | Purification, discipline, and festival honor. |

| Jainism | Paryushana / Santhara | Karmic cleansing and non-violence. |

| Buddhism | Monastic (no food after noon) | Alertness, mindfulness, and detachment. |

| Zoroastrianism | Nabor days (meat abstinence) | Moderation and avoidance of excess. |

The “Proof of Truth” Argument: Zia H. Shah’s Commentary

A modern and profound embellishment to the commentary on Quran 2:183 is provided by Dr. Zia H. Shah, Chief Editor of The Muslim Times. Shah posits that this verse serves as a verifiable “sign” (ayah) for the divine origin of the Quran based on its historical and geographical accuracy regarding the universality of fasting.

The Historical Impossibility of Human Knowledge

Shah argues that at the time of the Quran’s revelation in 7th-century Arabia, there were no libraries, no digital databases, and no widespread historical knowledge of global religious practices beyond the immediate Semitic region. The Prophet Muhammad, who was unlettered (ummi), could not have possessed ethnographic data concerning the indigenous populations of the Americas or Australia.

However, modern anthropological and archaeological research has confirmed that fasting was indeed a “prescribed” and “written” practice among these isolated populations centuries before they had any contact with the Abrahamic world. This confirms the Quranic statement that fasting was “prescribed for those before you” in a global, universal sense.

Evidence from the “New World” and Australia

Shah highlights several examples that “embellish” the truth of the verse:

- Australian Aboriginal Traditions: While not a universal law for every tribe, many Aboriginal groups utilized fasting as a central element of rites of passage and spiritual initiation. Young individuals would undergo periods of food and water abstinence to attain spiritual insights and connect with the “Dreamtime”.

- Native American Traditions: Fasting is an integral component of the “Vision Quest” practiced by tribes such as the Ojibwe and Menominee. Seeking spiritual guidance, an individual would retreat into solitude and fast for several days to receive a vision or a message from the Creator.

- The Sun Dance: Among the Plains tribes, the Sun Dance involves prolonged periods of fasting as a form of communal sacrifice and purification for the renewal of the world.

- Inca and Aztec Civilizations: Historical records of the Inca Empire and indigenous peoples of Mexico indicate that fasting was used to appease deities and avert catastrophe.

For Shah, the fact that a text revealed in an isolated desert culture could accurately claim the universality of a ritual discovered in far-flung continents over a millennium later is an intellectual miracle. It suggests that the “Author” of the Quran is the same as the “Author” of human history and biology.

Philosophical Inquiry: Al-Ghazali’s “Secrets of Fasting”

The philosophical dimensions of fasting are perhaps best articulated in the Ihya Ulum al-Din by Imam Al-Ghazali, who views Sawm as an essential tool for the “revival” of the heart. Al-Ghazali focuses on the “secrets” or internal realities of fasting that move the practice beyond physical hunger.

The Hierarchy of Fasting

Al-Ghazali identifies three distinct levels of fasting:

- The Fast of the Ordinary People (Sawm al-Umum): This involves merely fulfilling the legal requirement of abstaining from food, drink, and sexual gratification.

- The Fast of the Elect (Sawm al-Khusus): This level involves restraining the senses and the limbs from any form of sin or transgression.

- The Fast of the Elect of the Elect (Sawm al-Khusus al-Khusus): This is the ultimate level, where the heart itself “fasts” by turning away from all worldly thoughts and focusing entirely on God.

The Sensory Fast

For the “Elect,” fasting requires a rigorous monitoring of the inputs and outputs of the human experience. Al-Ghazali details six specific requirements for this level of fasting:

- Fasting with the Sight: Restraining the eyes from looking at anything that is prohibited or that distracts the heart from the remembrance of God.

- Fasting with the Tongue: Abstaining from gossip, lying, backbiting (ghibah), and quarreling. The tongue should instead be occupied with dhikr (remembrance) and the recitation of the Quran.

- Fasting with the Ears: Refraining from listening to illicit or useless speech, as “whatever is forbidden to say is forbidden to listen to”.

- Fasting with the Limbs: Keeping the hands and feet from engaging in any harmful or blameworthy acts.

- Moderation in Food: Avoiding the common pitfall of overeating at the time of breaking the fast (iftar). Al-Ghazali warns that stuffing oneself at night defeats the purpose of the fast, which is to “break” the desires of the lower self.

- A Balance of Hope and Fear: Maintaining a state of humility after the fast, wondering whether one’s effort was accepted by the Divine.

Fasting as a Shield Against Satan

Philosophically, fasting is viewed as a means to “defeat the foe of God”. Al-Ghazali teaches that Satan influences the human heart primarily through its desires and appetites (shahawat). By voluntarily restricting these appetites, the believer “constricts the pathways” of temptation, effectively silencing the whispers of the ego. Fasting is thus not a “penalty” but a “liberation” from the shackles of biological determinism.

Theological Significance: The Nearness of God and Taqwa

Theologically, verse 2:183 is deeply connected to the verses that follow, particularly verse 2:186: “When My servants ask you concerning Me, then surely I am near”. This juxtaposition suggests that the physical rigors of the fast are the necessary precursor to spiritual proximity.

The Hidden Worship

A fundamental theological aspect of fasting is its “hidden” nature. Unlike prayer, which involves observable movements, or charity, which involves an exchange of goods, fasting has no outward manifestation. A person could secretly eat and no one but God would know. This unique quality is why a famous Hadith Qudsi states: “Every good deed of the son of Adam is for him, except fasting, for it is for Me and I am its reward”. Fasting is the ultimate test of sincerity (ikhlas), as it is performed purely for the unseen Creator.

Fasting as a Medicine for the Soul

The theological commentary frequently uses the metaphor of “medicine” to describe the fast. Just as a physician prescribes a bitter medicine to cure a physical ailment, the “Divine Healer” prescribes the fast to cure the spiritual ailments of heedlessness (ghaflah) and arrogance. The “bitterness” of hunger is the necessary treatment for the “poison” of excessive desire. By the end of the month, the believer is expected to have undergone a “metabolic shift” in their spiritual character, emerging more patient (sabr), grateful (shukr), and conscious (taqwa).

Biological and Scientific Insights: The Signs of Autophagy

The Quranic discourse on ayat (signs) suggests that divine truth is reflected in the natural world. Contemporary scientific research into the effects of fasting provides a material commentary on the wisdom of the fast established in 2:183.

The Mechanism of Autophagy

One of the most significant biological discoveries related to fasting is autophagy, a cellular “cleaning” process discovered by Dr. Yoshinori Ohsumi in the 1990s. When the body enters a state of nutrient deprivation (starvation or fasting), the cells begin to recycle their own damaged or dysfunctional components.

- Cellular Maintenance: Damaged organelles like mitochondria are enveloped in a membrane and transported to lysosomes where they are broken down and reused.

- Disease Prevention: This process helps protect against neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, and infections by removing toxic proteins and pathogens.

- Anti-Aging: By recycling old cellular components, the body essentially “rejuvenates” itself at a molecular level.

From the perspective of Dr. Zia H. Shah, the fact that Islamic fasting (intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset) triggers these beneficial metabolic states is a testament to the “perfect harmony” between the Islamic religion and human nature (fitrah). The fast is not just a spiritual command; it is a biological necessity for long-term health and vitality.

Psychological Self-Regulation and Resilience

The science of psychology provides further evidence for the benefits of the Ramadan discipline.

- Self-Regulation Theory: Fasting intensity is strongly correlated with improved self-regulation (the ability to manage thoughts, emotions, and behavior). Research indicates that voluntary fasting can contribute up to 71.4% to an individual’s self-regulatory capacity.

- Delayed Gratification: The “Marshmallow Study” highlights the connection between success and the ability to delay gratification. Fasting is a rigorous exercise in this exact skill, training the brain to prioritize long-term goals over immediate impulses.

- Neuroplasticity: Fasting has been shown to stimulate the release of endorphins and ketones, which enhance cognitive focus and emotional resilience.

| Biological/Psychological Benefit | Mechanism | Connection to Quran 2:183 |

| Autophagy | Cellular recycling of damaged proteins | Manifestation of the “cleansing” promised by Taqwa. |

| Neuroplasticity | Ketone production and stress resistance | Supports the “mental clarity” required for deep reflection. |

| Self-Regulation | Strengthening of executive function | The practical application of Sawm (restraint). |

| Emotional Detox | Reduction in stress and anxiety levels | Realization of the “tranquility” intended by the Law. |

The Ethos of Fasting: Compassion, Discipline, and Ethics

The legislative intent of verse 2:183 extends beyond the individual to the social and ethical spheres. Fasting serves as a profound tool for social transformation by leveling the experience of all members of the community.

The Expansion of Compassion

Fasting creates a shared human experience of vulnerability. By experiencing the physical pangs of hunger and thirst, the believer moves from “pity” (an external feeling) to “empathy” (an internal experience). This shared suffering is the foundation of Islamic charity (zakat and sadaqah). When the wealthy fast, they are reminded that their sustenance is a gift from God, and they develop a visceral connection to those for whom hunger is a daily reality, not a monthly ritual.

The Discipline of the Message

Fasting also serves as a training ground for “people of an important message”. The strictness of the timings—not breaking the fast a minute early and not delaying it without cause—teaches a discipline that is essential for social progress. This discipline prevents fanaticism by operating within the strict bounds of the law, while simultaneously preparing the individual for the “struggle” (jihad) of life. It is a “social movement” that has the power to transform behavior, attitude, and outlook toward life.

Economic and Legal Ethics

The placement of the fasting verses in the Quran is also significant. Immediately following the injunctions on fasting is verse 2:188, which warns against the “unjust acquisition” of property and bribery. This sequence suggests that the self-control learned through abstaining from food and drink must translate into ethical conduct in business and law. If a person can refrain from their own lawful food for the sake of God, they should be even more capable of refraining from the unlawful property of others.

Thematic Epilogue: Fasting as the Bridge of Human Transcendence

In the final analysis, Quran 2:183 presents a vision of the human being as a creature of two worlds—the material and the spiritual. Fasting is the bridge that connects these worlds. It is the “gateway of worship” that allows the spirit to soar by temporarily grounding the body.

The “proof” of the Quran, as articulated by Dr. Zia H. Shah, lies in the fact that this ancient command anticipated the universal needs of the human species. Whether in the desert of Arabia, the forests of the Americas, or the plains of Australia, the human soul has always sought transcendence through the sacrifice of its physical appetites. The Quran codifies this universal urge into a structured, monthly discipline that balances the needs of the individual with the needs of society, and the laws of biology with the laws of the spirit.

Fasting is not an end in itself; it is a means to attain Taqwa—that state of profound awareness where the believer recognizes the nearness of God in every breath and every pang of hunger. Through the “hidden” sacrifice of Sawm, the believer is reminded that they are not merely biological machines driven by instinct, but spiritual beings endowed with the power of choice and the potential for holiness. As the moon of Ramadan waxes and wanes, it serves as a celestial reminder that the human condition is one of constant renewal, and that through the discipline of the fast, the soul can return to its original state of purity and peace.

The enduring relevance of verse 2:183 lies in its ability to address the modern crisis of distraction and over-consumption. In a world of “burning hot” pebbles and digital noise, the fast remains a cool sanctuary of silence and restraint. It is the “Criterion” that allows the believer to distinguish between the essential and the ephemeral, between the hunger of the body and the hunger of the soul. In doing so, the Quranic fast fulfills its ultimate promise: to guide humanity back to the “right way” through the transformative power of Taqwa.

Leave a comment