Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Introduction: The Convergence of Mathematics and Observation

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics stands as a monumental ratification of one of the most profound and disturbing predictions of modern science: the black hole. Divided between Sir Roger Penrose for his theoretical proofs and the duo of Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez for their observational triumph, the prize bridges a fifty-year gap between the chalkboards of 1960s mathematical relativity and the adaptive optics of 21st-century astronomy. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the scientific journey that led to this accolade, designed to serve as a foundational dossier for high-level dissemination, such as an in-depth podcast series or a documentary feature. It explores the intricate history of General Relativity’s most pathological prediction, the technological arms race to peer through the dusty heart of the Milky Way, and the resulting confirmation of a supermassive black hole—Sagittarius A*—lurking in our own galactic backyard.

For decades, black holes existed in a state of ontological limbo—accepted as solutions to Einstein’s equations but suspected by many, including Einstein himself, to be physical impossibilities that nature would abhor. The transformation of the black hole from a mathematical artifact to a physical reality is a saga of intellectual courage and engineering prowess. It involves the invention of new topological mathematics to describe the “end of time,” and the development of optical systems capable of correcting the turbulent blurring of Earth’s atmosphere in real-time.

This report synthesizes the theoretical underpinnings established by Penrose, who showed that the collapse of matter into a singularity is a robust prediction of General Relativity, with the empirical rigor of Genzel and Ghez, who spent thirty years tracking the motions of stars orbiting an invisible point in Sagittarius. Furthermore, it integrates the human elements—the rivalries, the eccentricities, and the pedagogical analogies—that make this scientific endeavor a compelling narrative for a general audience.

Part I: The Theoretical Wilderness (1915–1965)

1.1 The “Schwarzschild Singularity” and Early Skepticism

The story begins in 1916, mere months after Albert Einstein published his field equations of General Relativity. Karl Schwarzschild, serving on the German front during World War I, derived the first exact solution to these equations for a single spherical mass. The solution contained two singularities: one at the “Schwarzschild radius” (rs=2GM/c2) and one at the center (r=0).

While the singularity at the radius was later understood to be a coordinate artifact—an illusion vanishable by changing mathematical perspectives—the singularity at the center represented a genuine breakdown of the theory. At this point, density and curvature became infinite, and spacetime ceased to exist. For the first half of the 20th century, this “Schwarzschild singularity” was viewed with deep suspicion. The prevailing consensus was that it was a pathology arising from the unrealistic assumption of perfect spherical symmetry. Physicists believed that in a real star, perturbations, rotation, and internal pressure would disrupt the collapse, causing matter to “bounce” or settle into a dense, finite state rather than compressing to a point.

1.2 The Oppenheimer-Snyder Model vs. The Russian School

In 1939, J. Robert Oppenheimer and his student Hartland Snyder published a seminal paper describing the collapse of a dust cloud. By idealizing the star as a sphere of pressureless dust, they calculated that it would indeed collapse indefinitely, cutting itself off from the rest of the universe. This was the first mathematical description of what would later be called a black hole.

However, the scientific community largely dismissed the Oppenheimer-Snyder result as a “toy model.” The assumption of zero pressure and perfect symmetry was deemed too far removed from physical reality. The skepticism was championed by the “Russian School” of cosmology, led by Evgeny Lifshitz and Isaac Khalatnikov. They attempted to prove that under generic conditions—where stars are lumpy, rotating, and asymmetrical—singularities would not form. Their hypothesis was that as matter collapsed, the irregularities would cause particles to miss the center, generating a complex “bounce” rather than a singularity. This belief that nature protects itself from singularities held sway until the mid-1960s.

1.3 Penrose’s Topological Revolution (1965)

The deadlock was broken by Roger Penrose in 1965, a year often cited as the beginning of the “Golden Age” of General Relativity. Penrose’s innovation was to abandon the attempt to solve Einstein’s complicated differential equations directly, which was analytically impossible for asymmetrical systems. Instead, he introduced the tools of global topology and differential geometry to the problem.

1.3.1 The Concept of the Trapped Surface

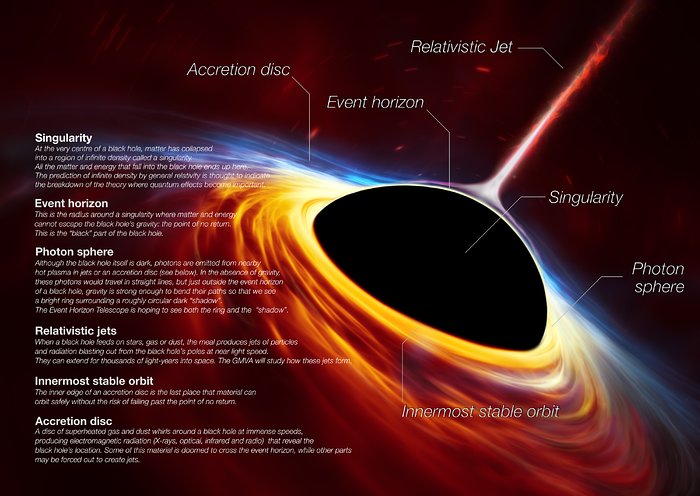

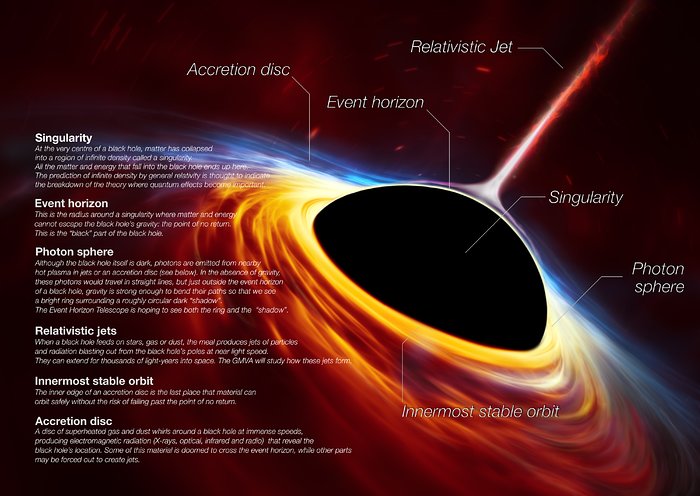

Penrose introduced a radical new geometric concept: the “closed trapped surface.” In ordinary space, if a flash of light is emitted from a sphere, the outgoing rays diverge (spread out) and the ingoing rays converge. Penrose envisioned a region of spacetime curved so intensely by gravity that both the ingoing and outgoing light rays converge toward the center. Once such a surface forms, there is no direction that leads “out.” All future-directed paths, whether for light or matter, are bent inward.

To explain this to a lay audience, Penrose often uses the analogy of a “waterfall” of space. Imagine space itself flowing inward like a river toward a waterfall. As one approaches the edge, the current speeds up. At the event horizon, the space is flowing inward at the speed of light. A fish (representing a photon) swimming upstream at maximum speed would remain stationary at the horizon. Inside the horizon, space flows faster than light; even if the fish swims directly upstream, it is carried backward toward the singularity.

1.3.2 The Singularity Theorem

Penrose’s Nobel-winning theorem proved that once a trapped surface forms, a singularity is inevitable, regardless of the star’s symmetry. He demonstrated that deviations from spherical symmetry (lumpiness) could not prevent the collapse. As long as the matter possessed positive energy (the “weak energy condition”), gravity would always be attractive and strong enough to force the spacetime geodesics to terminate.

This was the death knell for the Russian School’s skepticism. Penrose showed that black holes were not artifacts of idealization but “robust predictions” of the theory. A collapsing star does not need to be perfect to die; it simply needs to be massive enough. This insight fundamentally changed our understanding of the universe, suggesting that it is punctuated by points where the laws of physics dissolve.

Part II: The Challenge of the Galactic Center

While Penrose was redefining the theoretical landscape, observational astronomers faced a daunting challenge: finding these “robust predictions” in the real universe. The search focused on the center of the Milky Way, the closest galactic nucleus to Earth.

2.1 The Dust Curtain and the Infrared Window

The Galactic Center (GC) is located approximately 26,000 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius. However, visible light from the core is almost entirely blocked by vast clouds of interstellar dust and gas lying in the galactic plane. This dust absorbs visible photons, making the center invisible to traditional optical telescopes. To peer through this “fog,” astronomers must utilize longer wavelengths, such as radio and infrared, which can pass through the dust clouds relatively unimpeded.

In the 1970s, radio astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert Brown identified a compact, bright radio source at the dynamical center of the galaxy, which they named Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). The asterisk was added to denote that the source was “exciting,” in the nomenclature of atomic physics. While radio waves revealed the location of the suspect, they could not easily resolve the motion of individual stars needed to “weigh” the object.

2.2 The Rivalry: Genzel vs. Ghez

The quest to weigh Sgr A* sparked one of the great modern scientific rivalries. Two independent teams embarked on a decades-long race to track the stars at the galactic center:

- The Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE): Led by Reinhard Genzel in Garching, Germany. This team utilized the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) telescopes in Chile, first the New Technology Telescope (NTT) and later the Very Large Telescope (VLT).

- The UCLA Galactic Center Group: Led by Andrea Ghez in Los Angeles, USA. This team utilized the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

This competition was intense and productive. As Ghez noted in interviews, “There’s nothing like competition to keep you going,” driving both teams to verify each other’s data and push technological boundaries. The existence of two independent datasets using different telescopes in different hemispheres was crucial for the eventual scientific consensus; extraordinary claims require independent verification.

2.3 The Atmosphere as the Enemy

The primary obstacle for both teams was not the dust (which infrared cameras could bypass) but the Earth’s atmosphere. Turbulent air currents cause the refractive index of the atmosphere to fluctuate rapidly, blurring incoming starlight. This effect, known as “seeing,” limits the resolution of ground-based telescopes. Without correction, a massive 10-meter telescope has the same resolving power as a backyard hobbyist’s telescope.

Ghez uses vivid analogies to explain this challenge. She compares looking through the atmosphere to “looking at a pebble on the bottom of a stream through moving water.” The image of the pebble dances and distorts. Another analogy she employs is the “bug splat” pattern: a long exposure of a star through turbulence looks like a messy splatter rather than a point. To obtain a clear image, one must remove this “twinkle”.

2.4 The Technological Solutions: Speckle and Adaptive Optics

2.4.1 Speckle Imaging (The Early Years)

In the 1990s, both teams used a technique called Speckle Imaging. Instead of taking a long exposure (which blurs the image), they took thousands of ultra-short exposures (milliseconds). Each snapshot “froze” the atmospheric turbulence, revealing the star as a pattern of speckles. Computers then shifted and added these speckles together to reconstruct the image. Ghez refers to this as “the poor woman’s adaptive optics”. It was effective but computationally expensive and limited to bright stars.

2.4.2 Adaptive Optics (The Revolution)

The true breakthrough came with Adaptive Optics (AO). This technology involves a flexible, deformable mirror placed in the telescope’s optical path.

- Mechanism: A wavefront sensor measures the distortion of incoming light hundreds to thousands of times per second. A computer calculates the necessary correction and sends signals to actuators behind the deformable mirror. The mirror physically changes shape to cancel out the atmospheric distortion.

- Analogies: Ghez compares the distorted light wavefront to a “Pringle’s potato chip” (wavy and irregular) and the goal of AO is to flatten it back into a “pancake” (flat and uniform). She also likens the atmosphere to a “circus funhouse mirror” that distorts the image; AO introduces a second mirror with the exact opposite distortion to nullify the effect.

- Laser Guide Stars: Since AO requires a bright reference star to measure distortion, and the Galactic Center is dark in the visible spectrum, both teams used powerful lasers to excite sodium atoms in the upper atmosphere, creating an “artificial star” or “laser guide star” to lock onto.

This technology improved image clarity by a factor of 1,000, allowing the teams to distinguish individual stars in the crowded cluster surrounding Sgr A*.

Part III: The Discovery of the Monster

3.1 The Dance of the S-Stars

With AO, the teams began to track the positions of specific stars over years. These stars, known as the “S-stars” (MPE) or “S0-stars” (UCLA), are young, massive B-type stars. The most important of these is S2 (MPE) or S0-2 (UCLA).

S2 is the “hero” of the discovery. It orbits Sgr A* with a period of roughly 16 years. In comparison, the Sun takes 200 million years to orbit the galaxy. The short period of S2 meant that astronomers could observe a full orbit within a human career span, providing a complete geometric solution to the mass problem.

3.2 The Keplerian Proof

By 2002, S2 had completed its closest approach (pericenter) to the black hole. The velocity of the star at this point was staggering—over 7,000 km/s, or nearly 3% of the speed of light. By applying Kepler’s laws of planetary motion to the orbit of S2, the teams calculated the mass enclosed within its orbit.

The results were definitive:

- Enclosed Mass: Approximately 4.1 million solar masses.

- Radius: This mass was confined within a radius of less than 17 light-hours (about 120 AU, or roughly the size of our solar system).

3.3 Eliminating the Alternatives

Before these precise measurements, skeptics argued that the mass at the center could be a dense cluster of dark stars (neutron stars, white dwarfs) or exotic matter (fermion balls). However, the S2 orbit ruled these out.

- Cluster Instability: A cluster of 4 million solar masses packed into such a small volume would be dynamically unstable. The stars would collide and merge or evaporate on timescales much shorter than the age of the galaxy.

- Density: The density required to explain the S2 orbit leaves a supermassive black hole as the only explanation consistent with standard physics. As Genzel stated, “The black hole is the most plausible explanation” because any other configuration would collapse into a black hole anyway.

3.4 The “Paradox of Youth” and G-Objects

The discovery led to new mysteries. The S-stars are young, massive stars that should not exist so close to a black hole. The tidal forces in the region should tear apart the gas clouds needed to form stars. This is known as the “Paradox of Youth.”

- Hypothesis: Ghez suggests these stars might be the result of a “migration” from further out, or perhaps formed via a different mechanism involving the compression of gas by the black hole itself.

- G-Objects: Ghez’s team also discovered a new class of objects called “G-objects” (G1, G2, etc.). These mysterious bodies look like gas clouds but orbit like stars. Ghez hypothesizes they are binary stars that merged due to the black hole’s influence, bloating into large, dusty envelopes. This suggests the black hole drives a complex “stellar ecology” in the galactic center, merging and shaping the stars around it.

Part IV: Testing Einstein in the Strong Field

The 2020 Nobel Prize recognized the discovery, but the work continued. The Galactic Center became a laboratory for testing General Relativity in the “strong field regime”—a gravitational environment far more extreme than our solar system.

4.1 Gravitational Redshift (2018)

In May 2018, S2 passed pericenter again. Genzel’s team, using the new GRAVITY instrument (which combines four VLT telescopes into a super-interferometer), measured the light from S2 with unprecedented precision. They detected Gravitational Redshift: the light from the star was stretched to longer wavelengths as it climbed out of the black hole’s gravitational well. The measurement matched Einstein’s prediction to within 5%, marking the first detection of this effect around a supermassive black hole.

4.2 Schwarzschild Precession (2020)

In 2020, Genzel’s team confirmed another relativistic effect: Schwarzschild Precession. In Newtonian physics, a single planet orbits in a closed ellipse. In General Relativity, the orbit rotates (precesses) over time, tracing a “rosette” pattern. This effect was famous for proving Einstein right regarding Mercury’s orbit in 1915. Detecting it in S2’s orbit around a 4-million-solar-mass black hole confirmed that the object behaves exactly like a Kerr black hole, scaling up Einstein’s theory by orders of magnitude.

Part V: The Physics of the Monster (Podcast Deep Dive)

This section synthesizes the physical properties of the discovered object, utilizing the analogies and explanations found in the research to aid public understanding.

5.1 The Anatomy of Sagittarius A*

Based on the combined work of Penrose, Genzel, and Ghez, we can construct a physical profile of Sgr A*:

- Mass: 4.154±0.014×106M⊙.

- Event Horizon Radius: ∼12 million kilometers (0.08 AU). If placed in our solar system, the event horizon would fit inside the orbit of Mercury.

- Spin: The black hole is likely rotating, creating an ergosphere—a region outside the horizon where space is dragged around at superluminal speeds. Penrose theoretically proved energy could be extracted from this region (the Penrose Process), fueling the “jets” seen in other galaxies, though Sgr A* is currently quiescent.

5.2 Spaghettification and Tidal Forces

A key concept for any general audience is “spaghettification,” a term popularized by Stephen Hawking but grounded in the tidal force mechanics Penrose analyzed.

- The Mechanism: Gravity weakens with distance (1/r2). If an astronaut falls feet-first toward a black hole, their feet are closer to the center than their head. The pull on the feet is stronger.

- The Effect: This differential pull stretches the body vertically and compresses it horizontally. Ghez describes it as being “stretched out like a noodle”.

- The Sgr A Twist:* Counter-intuitively, spaghettification is weaker for larger black holes. For a supermassive black hole like Sgr A*, the event horizon is so far from the singularity that the difference in pull between head and feet is negligible at the crossing point. An astronaut could cross the horizon of Sgr A* without feeling anything locally, only to be destroyed closer to the central singularity.

5.3 Time Dilation: The “Frozen Star”

For a distant observer (like Genzel or Ghez on Earth), time near the black hole runs slower.

- The Calculation: At just 1 meter from the event horizon, time would run 100,000 times slower than on Earth.

- The Visual: An object falling in would appear to slow down and fade to red (redshift) as it approaches the horizon, eventually “freezing” there. It would never be seen crossing the line. This is why early Soviet physicists called black holes “frozen stars”.

5.4 The “Feast or Snack” Analogy

Why is Sgr A* so dim compared to Quasars? Ghez explains that black holes are “messy eaters.” They don’t suck everything in like a cosmic vacuum cleaner (a myth she actively debunks). Unless matter is aimed directly at them, it will simply orbit. Currently, Sgr A* is on a “starvation diet,” consuming very little matter—more like a “snack” than the “Thanksgiving feast” of a Quasar.

Part VI: The Human Element and Future Outlook

6.1 Personalities and Eccentricities

The 2020 prize also celebrated unique personalities in science.

- Roger Penrose: Known for his maverick ideas, Penrose is not just a physicist but a philosopher of consciousness and a recreational mathematician (famous for Penrose Tilings). When the Nobel committee called, he was at home getting a haircut. He later quipped that he had to cut his own hair during lockdown and didn’t do as good a job as his barber. He also holds controversial views on “Conformal Cyclic Cosmology” (CCC), believing our universe is just one “aeon” in an infinite cycle, and that “Hawking Points” in the sky might be signals from a previous universe.

- Andrea Ghez: A role model for women in STEM, Ghez emphasizes resilience. She advises her students (and her own children) that “good faceplants are really important in life,” encouraging a mindset where failure is a stepping stone. She also describes the difficulty of balancing a career and family, noting the importance of institutional support like daycare.

- Reinhard Genzel: A driven experimentalist who grew up building spectrometers in his attic and nearly injuring himself with home chemistry experiments involving bromium hydride. His rivalry with Ghez was professional but intense, driving the field forward.

6.2 The Future: The Event Horizon Telescope and Beyond

The discovery of Sgr A* was a prelude to the visual confirmation. In 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration released the first direct image of Sgr A*, showing a ring of glowing gas around a central shadow. This image was consistent with the mass and distance predictions made by Genzel and Ghez, serving as the “icing on the cake” for their Nobel-winning work.

The future involves the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). These next-generation instruments will have even higher resolution, potentially allowing astronomers to test General Relativity to its breaking point and perhaps glimpse the quantum nature of the singularity that Penrose proved must exist.

Conclusion

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics tells a story of convergence. It brings together the abstract, topological proofs of Roger Penrose—who showed that the universe contains its own end—with the concrete, grit-and-glass observations of Genzel and Ghez. Together, they transformed the black hole from a “mathematical ghost” into the gravitational anchor of our galaxy.

For the general public, this discovery changes our relationship with the cosmos. We now know that we orbit a monster. A “heavy, invisible object” that shapes the destiny of the Milky Way. Through the use of ingenious analogies—waterfalls of space, pringles-shaped light waves, and cosmic spaghetti—these scientists have not only discovered the dark heart of the galaxy but have given humanity the language to understand it.

Appendix A: Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: The Galactic Center Black Hole (Sgr A) Vital Statistics*

| Parameter | Value | Notes | Source |

| Mass | 4.154±0.014×106M⊙ | Precise measurement via S2 orbit | |

| Distance | 26,673±42 light-years | Distance from Earth | |

| Event Horizon Radius | ∼12×106 km | Schwarzschild radius (2GM/c2) | |

| Apparent Size | ∼50 micro-arcseconds | Size of a donut on the Moon | |

| Spin | Non-zero | Inferred from flares and EHT data |

Table 2: Comparison of Observing Techniques

| Feature | Speckle Imaging (1990s) | Adaptive Optics (2000s–Present) |

| Method | Short exposures (“freezing” turbulence) | Real-time mirror deformation |

| Exposure Time | Milliseconds | Long exposures possible |

| Depth | Bright stars only (K < 16) | Fainter stars visible (K < 20) |

| Resolution | Diffraction limited (post-processing) | Diffraction limited (real-time) |

| Analogy | “Poor woman’s AO” | “Flattening the Pringle” |

| Key Limitation | Computational intensity | Requires Guide Star (Laser) |

| Source |

Appendix B: Key Analogies for Public Communication

Table 3: Analogies Used by the Laureates

| Concept | Analogy | Originator | Explanation | Source |

| Atmospheric Distortion | “Circus Funhouse Mirror” | Andrea Ghez | The atmosphere distorts light like a curved mirror; AO acts as a second mirror to correct it. | |

| Wavefront Error | “Pringle vs. Pancake” | Andrea Ghez | Distorted light is curved like a chip; corrected light is flat like a pancake. | |

| Event Horizon | “Waterfall of Space” | Roger Penrose | Space flows inward; at the horizon, it flows at the speed of light. | |

| Black Hole Feeding | “Snack vs. Feast” | Andrea Ghez | Sgr A* is currently fasting (snack), while Quasars are feasting (Thanksgiving dinner). | |

| Tidal Forces | “Spaghettification” | Hawking/Ghez | Differential gravity stretches objects vertically into noodle shapes. | |

| Galactic Geography | “Suburbs vs. Downtown” | Andrea Ghez | Earth is in the quiet suburbs; the Galactic Center is the busy, crowded downtown. |

This report constitutes a comprehensive synthesis of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics, integrated with specific narrative elements and analogies suitable for broad public dissemination.

Leave a comment