Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio summary:

Abstract

We can get into the brain of another person as a neurosurgeon but can never get into the mind of any other person other than ourselves. Only God can!

This report presents an exhaustive philosophical and biographical examination of the dialectic surrounding the ontology of the human mind, anchored in the intellectual trajectories of Dr. Stephen Law and Dr. Robert Lawrence Kuhn. The investigation is bifurcated into two primary domains: a rigorous biographical reconstruction of the interlocutors’ academic and professional evolutions, and a granular exegesis of their recorded discourse, “Is There Anything Non-Physical About the Mind?”

The biographical analysis traces Stephen Law’s unconventional ascent from postal worker to Oxford academic, highlighting his rigorous engagement with essentialism, Wittgensteinian linguistic analysis, and his provocative “Evil God Challenge” in the philosophy of religion. Simultaneously, it deconstructs Robert Lawrence Kuhn’s multidisciplinary career, spanning neurophysiology, international geopolitics, and his taxonomic approach to metaphysical inquiry via the Closer to Truth project.

The core of the report provides a timestamped, micro-analytical commentary on their dialogue, deconstructing arguments regarding the Causal Closure of the Physical, the Phenomenological Gap, and the Knowledge Argument. Central to this analysis is Law’s “Sugar Cube Analogy,” which is scrutinized through the lens of dispositional realism and analytic functionalism. The report integrates broader philosophical literature—including Kripkean metaphysics, Rylean behaviorism, and the “hard problem” of consciousness—to evaluate the viability of Law’s functionalist proposal against Kuhn’s “landscape” of consciousness theories. The document concludes with a thematic epilogue synthesizing the implications of these positions for human agency, identity, and the metaphysical conception of the self.

Part I: Intellectual Biographies and Theoretical Foundations

1. Dr. Stephen Law: The Analytic Iconoclast

1.1 From the Sorting Office to the Ivory Tower

The intellectual biography of Stephen Law is characterized by a distinctive trajectory that informs his philosophical style—one that prizes clarity, accessibility, and a rigorous refusal to be intimidated by established dogmas. Born on December 12, 1960, in Cambridge, England, Law did not follow the conventional Eton-to-Oxbridge pipeline that dominates much of the British philosophical establishment. His early adulthood was spent in the labor force as a postman, a role he occupied until he was “asked to leave”.

This departure from the postal service marked a pivotal inflection point. At the age of 24, Law entered City University London as a mature student. Despite lacking the standard A-level qualifications usually required for undergraduate admission, he persuaded the university to accept him—a gamble that yielded significant returns when he graduated with first-class honours in Philosophy. This academic success propelled him to the University of Oxford, specifically Trinity College, where he read for a B.Phil in Philosophy. His intellectual acumen was further recognized with a three-year stipendiary Junior Research Fellowship at The Queen’s College, Oxford, where he completed his doctoral research.

His D.Phil thesis focused on essentialism, the work of Saul Kripke, and the function of natural kind terms. This foundational work in the philosophy of language and metaphysics is crucial for understanding his later arguments in the philosophy of mind, particularly his use of the “Water/H2O” analogy to defend physicalism against dualist intuitions. The Kripkean notion of a posteriori necessity—that empirical discoveries (like water being H2O) reveal necessary truths about the nature of reality—serves as the bedrock for Law’s argument that the “feeling” of consciousness and the “firing” of neurons can be identical despite their conceptual distinctness.

1.2 The Pedagogy of Reason: Heythrop and Public Philosophy

Following his doctoral work, Law assumed a long-standing position as Reader in Philosophy and subsequently Senior Lecturer at Heythrop College, University of London. Heythrop, a specialist philosophy and theology college founded by the Jesuits, provided a unique environment for Law’s analytic atheism to interact with serious theological scholarship. He taught there until the college’s closure in 2018, after which he transitioned to his current role as Director of Studies in Philosophy at the University of Oxford’s Department for Continuing Education.

Law’s career is defined by a commitment to “public philosophy”—the conviction that philosophical tools should be accessible to the general public and applied to everyday reasoning. He is the editor of THINK: Philosophy For Everyone, a journal published by the Royal Institute of Philosophy intended to bridge the gap between academic journals and popular readership. Furthermore, as the Provost of the Centre for Inquiry UK, he has been a vocal advocate for humanism, secularism, and critical thinking, organizing events that challenge pseudoscience and religious privilege.

1.3 Major Works and Philosophical Themes

Law’s bibliography reflects a dual engagement with academic rigor and popular education. His works frequently employ dialogue, thought experiments, and reductio ad absurdum arguments to expose the fragility of irrational beliefs.

| Book Title | Year | Core Philosophical Themes |

| The Philosophy Files | 2000 | Introduction to metaphysics via “The Martian in the Machine” and other paradoxes. |

| The Philosophy Gym | 2003 | Winner of the Mindelheim Philosophy Prize. Uses dialogues (e.g., “What’s wrong with Gay Sex?”) to explore ethics and theology. |

| The War For Children’s Minds | 2006 | A critique of faith-based education. Argues for liberal moral education where children are encouraged to question authority rather than being indoctrinated. |

| Believing Bullshit | 2011 | An epistemological taxonomy of “intellectual black holes”—mechanisms that trap smart people in irrational beliefs (e.g., conspiracy theories, homeopathy). |

| Humanism: A Very Short Introduction | 2011 | A defense of secular ethics, arguing that meaning and morality do not require supernatural foundations. |

1.4 The “Evil God” Challenge: A Case Study in Symmetry

One of Law’s most significant contributions to the philosophy of religion, which indirectly informs his physicalist stance by undermining theistic dualism, is the “Evil God Challenge”. This argument is designed to neutralize standard theistic arguments (like the Cosmological Argument or Fine-Tuning Argument) by showing they function equally well for an absurd conclusion.

The argument proceeds structurally:

- The Theist’s Claim: The universe exhibits order, fine-tuning, and moral goodness, which are best explained by the existence of an omnipotent, omnibenevolent God.

- The Problem of Evil: Theists explain away suffering (cancer, natural disasters) using “theodicies” (e.g., suffering builds character, or is a result of free will).

- The Mirror Hypothesis: Law proposes an “Evil God” who is omnipotent and omnimalevolent.

- The Symmetry: An Evil God would also create a fine-tuned universe (to maximize the existence of sentient beings who can suffer). An Evil God would allow for some “good” (free will, pleasure) to exist, either to deepen the eventual suffering (contrast) or because it is a necessary byproduct of laws required for suffering.

- The Conclusion: If the “problem of good” can be explained away by the Evil God proponent just as easily as the “problem of evil” is explained away by the Good God proponent, then the empirical evidence does not favor a Good God over an Evil God. Since we intuitively reject the Evil God, we should arguably reject the Good God on the same evidentiary grounds.

This argument showcases Law’s analytic method: isolating the logical structure of a belief system and subjecting it to rigorous stress-testing via counterfactuals. This same method is applied in his philosophy of mind, where he isolates the “intuition of dualism” and subjects it to the “Elton John” stress test.

2. Dr. Robert Lawrence Kuhn: The Polymath of Existence

2.1 The Scientist-Philosopher-Strategist

Robert Lawrence Kuhn represents a unique archetype in the intellectual landscape: a figure who straddles the worlds of hard science, global finance, and metaphysical speculation. Born on November 6, 1944, in New York, Kuhn’s educational background provided a rigorous foundation for his later work in the philosophy of mind.

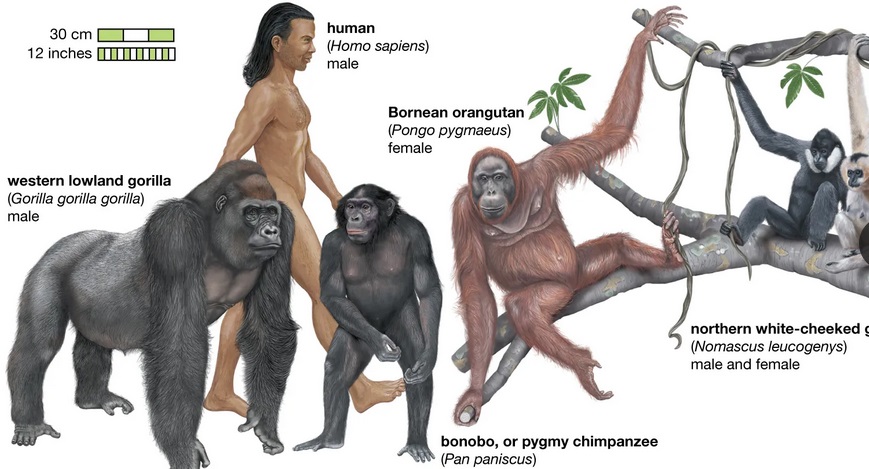

He began his academic journey at Johns Hopkins University, earning a B.A. in Human Biology (Phi Beta Kappa) in 1964. He then transitioned to the cutting edge of neuroscience, completing a Ph.D. in Anatomy and Brain Research at UCLA’s Brain Research Institute in 1968. This period was critical; Kuhn was trained during a burgeoning era of neurophysiology, giving him a “bottom-up” understanding of the brain as a biological machine. This training manifests in his interviews—he frequently references the specific mechanics of neurons, synapses, and cortical organization, preventing his philosophical speculations from drifting into scientific illiteracy.

However, Kuhn did not remain in the laboratory. In a significant pivot, he attended the MIT Sloan School of Management as a Sloan Fellow, earning an M.S. in Management in 1980. This propelled him into a career in investment banking and corporate strategy, fundamentally altering his worldview from that of a specialist researcher to a generalist systems thinker.

2.2 The China Advisor

Kuhn’s influence extends into the geopolitical arena. He is widely cited as one of the West’s most prolific interpreters of Chinese policy, having spent decades advising the Chinese government and facilitating Sino-American relations. He authored The Man Who Changed China: The Life and Legacy of Jiang Zemin, a biography that gave him unprecedented access to the Chinese leadership.

His contributions were formally recognized when he became one of only ten foreigners (and one of only two Americans) to receive the “China Reform Friendship Medal,” the country’s highest honor for foreign nationals, acknowledging his role in China’s “reform and opening up” over four decades. While some critics view his work as overly sympathetic to Beijing , his ability to navigate the complex ideological terrain of the Chinese Communist Party demonstrates a mind capable of engaging with radically different worldviews—a skill he applies directly to his philosophical work.

2.3 Closer to Truth and the Taxonomy of Consciousness

In 2000, Kuhn created Closer to Truth (CTT), a public television series and multimedia project dedicated to “Cosmos, Consciousness, and Meaning”. Unlike standard science journalism, CTT operates as a philosophical archive. Kuhn has conducted over 280 episodes and thousands of interviews with Nobel laureates, theologians, and philosophers.

Kuhn’s role in CTT is not merely that of a host but of a taxonomist. He seeks to categorize every possible answer to the “Big Questions.” In his recent extensive article, “A Landscape of Consciousness,” Kuhn developed a rigorous taxonomy of theories regarding the mind-body problem, classifying them into nine distinct categories :

| Category | Description |

| 1. Materialism/Physicalism | Consciousness is entirely physical; mental states are brain states. (Law’s position fits here). |

| 2. Epiphenomenalism | Mental states are caused by physical states but have no causal power over them. |

| 3. Non-Reductive Physicalism | Mental states are physical but cannot be reduced to lower-level physics. |

| 4. Quantum Consciousness | Consciousness arises from quantum mechanical phenomena (e.g., Penrose/Hameroff). |

| 5. Qualia Force | Consciousness is a fundamental force, akin to gravity or electromagnetism. |

| 6. Qualia Space | Consciousness exists in a separate dimensional space. |

| 7. Panpsychism | Consciousness is a fundamental feature of all matter, down to the electron. |

| 8. Dualism | Substance dualism; mind and body are distinct substances (Cartesian/Religious). |

| 9. Consciousness as Ultimate Reality | Idealism; only consciousness exists, and the physical world is an illusion or derivative. |

This framework informs his dialogue with Stephen Law. When Kuhn presses Law, he is not just asking random questions; he is testing where Law fits within this specific matrix, particularly challenging Law on the transition from Category 1 (Materialism) to Category 8 (Dualism) via the bridge of “Mystery”.

Part II: The Dialogue – A Micro-Analytical Commentary

3. Introduction to the Enquiry

Source Material: “Is There Anything Non-Physical About the Mind?” Participants: Robert Lawrence Kuhn (Host) and Stephen Law (Philosopher).

The dialogue serves as a microcosm of the analytic philosophy of mind, specifically the tension between the manifest image of man (how we feel) and the scientific image (what physics tells us). Kuhn plays the role of the “Incredulous Materialist”—one who accepts science but cannot shake the dualist intuition. Law plays the “Analytic Deflationist,” seeking to show that the mystery is a linguistic or conceptual confusion rather than an ontological one.

4. The Causal Exclusion Argument [00:00 – 01:45]

4.1 The Setup

The conversation begins with Kuhn’s confession: despite his Ph.D. in brain research, he cannot dismiss the possibility that the mind is non-physical [00:00]. This admission sets the stage for Law to introduce the most potent weapon in the physicalist arsenal: The Argument from Causal Closure.

4.2 The Logic of Closure

Law argues that the physical universe is a “causally closed system” [01:00]. This concept, central to modern metaphysics (often associated with philosophers like Jaegwon Kim and David Papineau), asserts that:

- Every physical effect (e.g., a hand moving) has a sufficient physical cause (e.g., muscle contraction $\leftarrow$ nerve impulse $\leftarrow$ motor cortex firing).

- Physics is comprehensive; it does not leave “gaps” for non-physical forces to intervene.

Law posits the dilemma:

- If the mind were non-physical (a soul, spirit, or ectoplasm), it would be distinct from the physical brain.

- We know the mind causes physical behavior (e.g., “I decide to wave my arm, and the arm waves”) [01:38].

- For a non-physical mind to cause a physical arm wave, it would have to exert force on the physical system.

- However, if the physical system is closed and already has sufficient physical causes (neurons), then the non-physical mind is either redundant (overdetermination) or impossible (violation of conservation of energy) [01:18].

Insight: Law is effectively utilizing the “Interactionist Problem” that plagued Descartes. Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia originally asked Descartes how an immaterial soul could push a material pineal gland. Law updates this by referencing the closure of modern physics: “If you want to say that the mind is not physical… you can’t have the mind affecting the physical world” [01:18]. Since we refuse to accept that our minds are impotent (Epiphenomenalism), we are forced to conclude the mind must be physical.

5. The Phenomenological Gap and the “Water” Analogy [02:00 – 05:00]

5.1 The Argument from Introspection

Kuhn pivots to the primary objection against physicalism: Introspection. He argues that the “feeling” of consciousness—the redness of a rose, the pang of sorrow—is qualitatively different from our understanding of matter [03:07]. “It feels different,” Kuhn insists. A “mushy mass of brain cells” passing sodium and potassium ions across membranes seems categorically distinct from the unified, technicolor experience of the self. This is the “Hard Problem” of consciousness (a term coined by David Chalmers, though not explicitly named by Law here).

5.2 The Kripkean Move: Water and H2O

Law responds by dismantling the authority of introspection. He argues that “appearances can be deceptive” [04:34]. To illustrate this, he employs the standard Kripkean analogy of Water and H2O.

- The Phenomenal Concept: Water appears as a clear, wet, drinkable liquid.

- The Scientific Concept: Water is a collection of H2O molecules.

- The Deception: Looking at water does not reveal its molecular structure. It does not “look like” hydrogen and oxygen. Yet, they are identical.

Law applies this to the mind:

- Looking at a thought from the “inside” (introspection) does not reveal its neural structure.

- Looking at a brain from the “outside” (neuroscience) does not reveal the subjective feeling.

- Conclusion: Just as Water is H2O despite the difference in appearance, a mental state is a brain state despite the difference in how it feels and how it looks [04:15].

Insight: Law is advocating for A Posteriori Physicalism. We cannot determine that Mind=Brain through logic alone (it’s not true by definition); we discover it scientifically, just as we discovered Water=H2O. The “gap” Kuhn feels is an epistemic gap (a gap in knowing), not an ontological gap (a gap in being).

6. The Knowledge Argument and the “Elton John” Analogy [05:15 – 07:20]

6.1 Mary’s Room (Implicit)

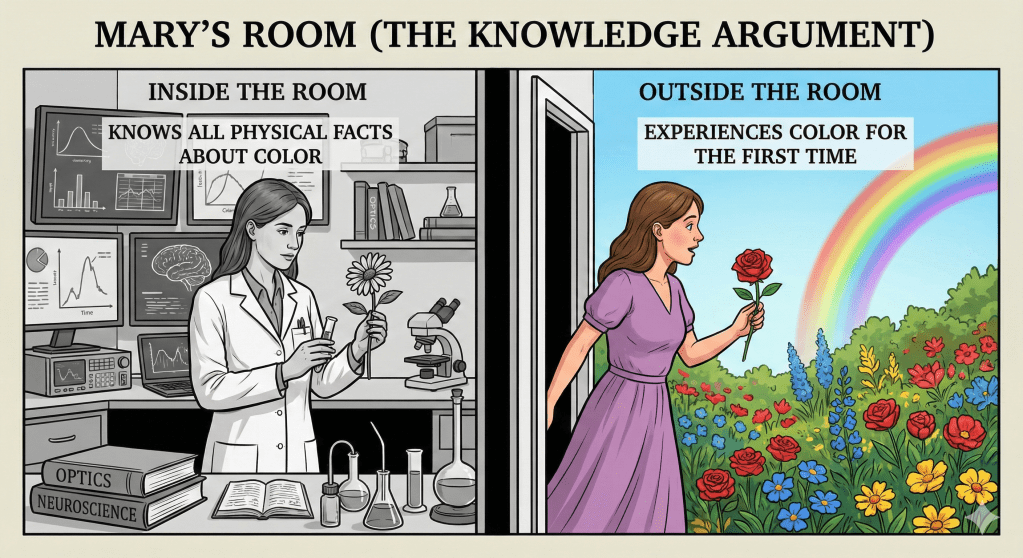

Kuhn invokes the Knowledge Argument, pointing out that one could theoretically know everything about the physics of the brain (every neuron, every synapse) and still not know “what it is like” to experience a specific sensation [05:47]. This is a reference to Frank Jackson’s “Mary the Color Scientist” thought experiment: Mary knows all the physical facts about color but has never seen it. When she sees red for the first time, does she learn something new? If yes, physicalism is false (because she knew all physical facts).

6.2 The “Elton John” Defense

Law attempts to neutralize the Knowledge Argument using a defense based on referential opacity and modes of presentation. He introduces the “Elton John” analogy.

- Premise: Elton John is identical to Reginald Dwight (his birth name). They are one person.

- Scenario: A person might know that “Elton John sang Rocket Man.” However, that same person might not know that “Reginald Dwight sang Rocket Man.”

- The Logical Flaw: The fact that you can know something about Elton John without knowing it about Reginald Dwight does not prove they are two different people. It only proves that you have two different “files” or “concepts” for the same person that you haven’t linked yet [06:45].

Application to Mind:

- Mary knows the “Reginald Dwight” facts (the neurophysiology of color).

- Mary does not know the “Elton John” facts (the subjective feeling of color).

- Conclusion: This ignorance does not prove that the “feeling” is separate from the “neurophysiology.” It just means Mary has two different ways of accessing the same physical reality—one via a textbook (third-person) and one via her visual cortex (first-person) [07:06].

Insight: This defense aligns Law with the Phenomenal Concept Strategy. He argues that the “feeling” is just a brain state accessed via a special “phenomenal concept” that we only acquire when we actually have the experience.

7. The Sugar Cube Analogy: A Functionalist Proposal [07:21 – 09:42]

7.1 Moving Beyond Identity Theory

While Law defends the Identity Theory (Mind=Brain) against attacks, he ultimately pivots to a more nuanced view: Functionalism or Dispositionalism. He explicitly states that he doesn’t want to say the mind is just “a blob of brain tissue” [09:29]. He seeks to avoid the crudeness of reductive materialism.

7.2 The Metaphysics of Solubility

Law introduces his central metaphor: The Sugar Cube [08:29].

- The Object: A sugar cube.

- The Property: Solubility (the ability to dissolve in water).

- The Mechanism: The micro-crystalline structure of the sugar molecules.

Law analyzes the relationship between these three elements:

- The micro-structure causes the dissolving.

- The micro-structure explains the solubility.

- Crucially: The solubility is not the micro-structure. Solubility is a dispositional property—it is the “would-be” of the object. It is defined by what the object does under certain conditions (if placed in water $\rightarrow$ dissolves).

7.3 The Mind as a Repertoire of Abilities

Law applies this directly to the mind-body problem:

- Brain: Analogous to the sugar’s micro-structure. It is the physical machine.

- Mind: Analogous to the solubility. It is not a “thing” or a “substance.” It is a “rich repertoire of abilities” and behavioral dispositions [08:09].

Law’s Thesis: “To have a mind is to have a set of abilities… to understand, to perceive, to think.” [09:25].

- Just as you wouldn’t say “solubility” is a ghost inside the sugar cube, you shouldn’t say the “mind” is a ghost inside the machine.

- Just as you wouldn’t strictly say “solubility is the shape of the molecules” (because different molecules like salt can also be soluble—Multiple Realizability), you shouldn’t say “mind is the C-fibers.” The mind is the function realized by the fibers.

Insight: This position is a blend of Rylean Behaviorism (mind is observable behavior) and Putnam’s Functionalism (mind is a functional state). By treating the mind as a cluster of dispositions, Law dissolves the “Interaction Problem.” Dispositions don’t “interact” with their basis; they are realized by it.

Part III: Theoretical Deep Dives and Broader Implications

8. Dispositional Realism vs. Instrumentalism

To fully appreciate Law’s “Sugar Cube” argument, we must situate it within the philosophy of science regarding dispositions.

- Instrumentalism: Views solubility merely as a conditional statement: “If X is in water, X dissolves.” There is no “state” of solubility inside the cube.

- Realism: Views solubility as a real, causal state of the object.

Law seems to adopt a Realist Functionalism. He believes the mind is “real”—it’s not just a way of talking (Instrumentalism). However, its reality is the reality of a power or capacity. This avoids the “Eliminativist” trap (saying the mind doesn’t exist) and the “Dualist” trap (saying the mind is a separate object). The “Sugar Cube” analogy also serves to demystify the Afterlife. If the mind is like solubility, and solubility depends on the micro-structure, then destroying the structure (crushing/burning the sugar) destroys the solubility. A disposition cannot exist without a categorical basis. Thus, Law’s view implies that a disembodied soul is as absurd as “disembodied solubility” floating around without a sugar cube.

9. Kuhn’s Taxonomy vs. Law’s Functionalism

How does Law’s view fit into Kuhn’s “Landscape of Consciousness”?

- Kuhn would likely classify Law under Physicalism (Category 1) or perhaps Non-Reductive Physicalism (Category 3). Law accepts that everything is physical (closure), but denies that mental concepts are identical to physical concepts (Elton John analogy) and treats mental properties as functional/dispositional states.

- The Conflict: Kuhn’s persistence in the interview suggests he finds this unsatisfactory. For Kuhn, Category 1 and 3 fail to account for Category 5 (Qualia Force) or 9 (Idealism).

- The Residue of Experience: Kuhn’s objection is that a “repertoire of abilities” (Law’s definition) describes a zombie. A philosophical zombie can behave like a human (has the repertoire) but lacks inner experience. Law’s functionalism defines the mind by what it does (behavior), but Kuhn defines the mind by what it feels (phenomenology). This remains the unbridgeable chasm in their dialogue.

10. The Theological Implications: Evil God and the Mind

While not explicitly discussed in the video, Law’s “Evil God Challenge” and his philosophy of mind are deeply interconnected.

- Dualism and Theism: Historically, Theism relies on Substance Dualism (the soul). The soul provides a way for humans to be distinct from the determined material world, allowing for free will and moral responsibility (which theists need to justify the existence of evil/suffering).

- Physicalism and Theodicy: If Law is right and the mind is just a physical “sugar cube” disposition, then libertarian free will is likely false (dispositions are determined by structure and laws of physics).

- The Trap: If humans are purely physical machines, the “Free Will Defense” for the problem of evil collapses. God would be directly responsible for the programming of the human “sugar cubes” that commit genocide. Thus, Law’s physicalism reinforces his atheistic critique: if there is no soul to insulate God from human action, the Problem of Evil becomes unsolvable, further supporting the “Evil God” symmetry (or the non-existence of God).

Epilogue: The Ghost in the Sugar Cube

The dialogue between Stephen Law and Robert Lawrence Kuhn serves as a masterclass in the friction between the Analytic and the Phenomenological approaches to existence.

Law represents the Analytic impulse: the drive to demystify, to categorize, and to dissolve paradoxes through linguistic precision. For Law, the “mystery” of the mind is a result of cognitive mismanagement—we are confusing “modes of presentation” (Elton John) with “modes of existence” (Reginald Dwight). By reframing the mind as a “repertoire of abilities” akin to the solubility of a sugar cube, Law offers a sanitized, functional universe where the “ghost in the machine” is exorcised—not by finding the ghost, but by realizing the machine is simply sufficiently complex to have “dispositions.”

Kuhn represents the Phenomenological impulse: the refusal to deny the primacy of the “raw feel.” His reluctance to accept the “Sugar Cube” solution highlights a deep human intuition that we are not merely “soluble.” We do not experience ourselves as bundles of dispositions waiting to be triggered by stimuli; we experience ourselves as unified centers of agonizing and ecstatic awareness.

Ultimately, the debate rests on whether one prioritizes the Third-Person perspective (science, observation, behavior, sugar cubes) or the First-Person perspective (feeling, qualia, the “I”). Law argues that the Third-Person perspective can explain the First-Person perspective (it’s just a brain state seen from the inside). Kuhn fears that the translation is impossible—that in reducing the mind to a physical disposition, we may have explained the behavior, but we have lost the person.

In the end, the “Sugar Cube” analogy is powerful because it is humble. It suggests that consciousness is not a divine spark or a mystical energy, but a mundane, fragile potentiality inherent in the structure of matter itself. We are soluble creatures, dissolving into the world of experience, dependent entirely on the precarious micro-structure of our brains.

Table 1: Comparative Taxonomy of Arguments Presented

| Argument Phase | Stephen Law (Analytic Physicalist) | Robert Lawrence Kuhn (Skeptical Interrogator) | Key Philosophical Concept |

| Causal Foundation | Causal Closure: Physics is complete. Non-physical minds cannot push physical atoms. | Interaction Problem: If mind is physical, does it lose its “specialness”? If non-physical, how does it move the arm? | Causal Closure of the Physical |

| Epistemic Gap | Posterior Identity: Water is H2O. We discover identity scientifically, not intuitively. | Introspection: “It feels different.” The raw data of consciousness contradicts materialism. | A Posteriori Necessity |

| Knowledge Gap | Elton John Analogy: Knowing “Elton” $\neq$ knowing “Reg.” Conceptual difference $\neq$ Ontological difference. | Mary’s Room: Knowing the physics doesn’t yield the experience. Knowledge seems incomplete. | Phenomenal Concept Strategy |

| Ontological Model | The Sugar Cube: Mind is a disposition/ability (solubility), not a substance. | The Hard Problem: Is a set of abilities sufficient to explain the feeling of being? | Analytic Functionalism |

Leave a reply to Zia H Shah Cancel reply