Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio summary:

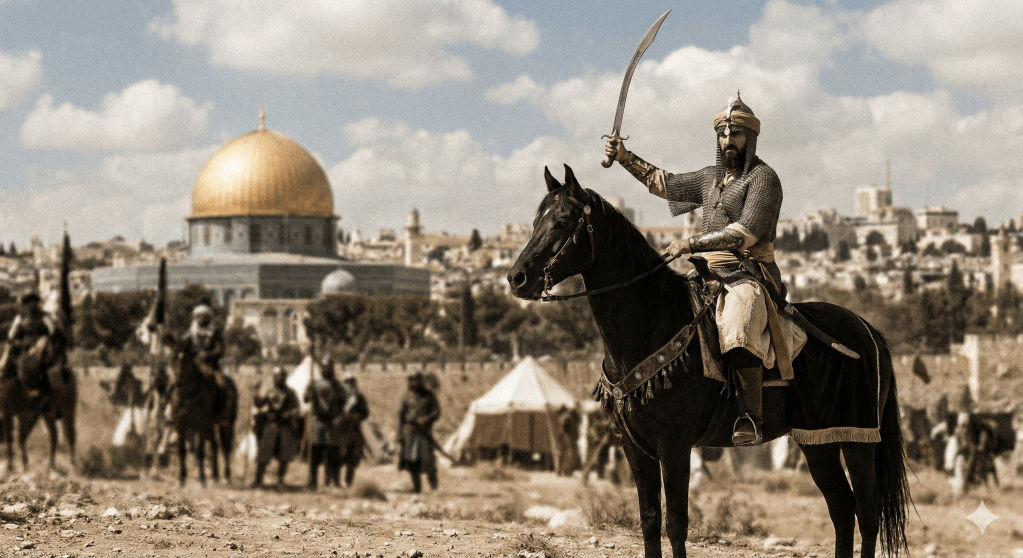

The Crescent and the Lion: A Comprehensive Historiographical and Thematic Analysis of the BBC’s “The Third Crusade: Saladin & Richard the Lionheart”

Introduction: The Convergence of Myth and History in the Medieval Near East

The historical narrative of the Crusades, specifically the Third Crusade (1189–1192), has long been dominated by the collision of two titanic figures: Yusuf ibn Ayyub, known to the West as Saladin, and King Richard I of England, the Lionheart. These two men have transcended the dry pages of medieval chronicles to become archetypes of chivalry, holy war, and leadership. The British Broadcasting Corporation’s documentary, The Third Crusade: Saladin & Richard the Lionheart, serves as a significant historiographical artifact that attempts to reconstruct the biographies of these leaders while navigating the complex cultural legacy they left behind. The film posits that the struggle for Jerusalem was not merely a territorial dispute over stone and sand, but a clash of civilizations driven by personal piety, dynastic ambition, and strategic genius.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the documentary’s narrative arc, historical assertions, and thematic undercurrents. It examines how the film constructs the memory of the Third Crusade, juxtaposing the rise of Saladin from Kurdish obscurity to the Sultanate of Egypt against the arrival of the Angevin warrior-king. furthermore, it integrates a “thematic epilogue” that expands beyond the film’s timeline to explore the modern geopolitical appropriations of Saladin’s image, particularly by 20th-century Arab nationalist leaders like Saddam Hussein and Gamal Abdel Nasser. Through a detailed examination of the video’s content, combined with supplementary historical context, this report elucidates the complex tapestry of faith, blood, and diplomacy that defined the era.

The documentary operates on a dual track: it is both a military history of the campaigns of 1187–1192 and a psychological profile of two men who, though they never met face-to-face, defined each other’s legacies. It challenges the monolithic view of the Crusades as a simple binary of Christian versus Muslim, revealing instead a world of internecine conflict, pragmatic diplomacy, and occasional interfaith respect. This analysis will traverse the narrative from the banks of the Tigris to the walls of Jerusalem, dissecting the BBC’s portrayal of the “virtuous pagan” and the “flawed crusader.”

Part I: The Forging of a Sultan

The Origins of Yusuf ibn Ayyub: Geography and Identity

The narrative commences by grounding the legendary figure of Saladin in the tangible realities of geography and lineage. Born in 1137 in Tikrit, a fortress town on the Tigris River in present-day Iraq, Saladin’s origins are distinct from the Arab hegemony that dominated the region’s political elite. He was ethnically Kurdish, a detail the documentary emphasizes to distinguish his heritage from the strictly Arab dynasties of the past. This detail is not merely biographical trivia; it underscores the meritocratic nature of the Islamic military hierarchy of the time, where a Kurd could rise to command the armies of the Caliphate.

The documentary draws a sharp, modern parallel by noting that Tikrit is also the birthplace of the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. This connection is pivotal for understanding the modern “afterlife” of Saladin. Saddam Hussein actively cultivated a personality cult that merged his identity with Saladin’s, commissioning murals and statues that depicted them as dual guardians of Tikrit, united across centuries by geography and a shared mission against Western imperialism. While the documentary uses this fact to anchor Saladin in a recognizable location for a modern audience, the implications run deeper: Saladin’s legacy has been secularized and weaponized by modern Ba’athist regimes to serve the purposes of Arab nationalism and anti-colonial resistance.

In his youth, Saladin is portrayed not as a zealot destined for holy war, but as a man of the world. He was a polo-playing cavalry officer, immersed in the martial culture of the Zangid dynasty but not yet burdened by the heavy mantle of destiny. This characterization humanizes the Sultan, suggesting that his transformation into the “Sword of Islam” was an evolution rather than an innate disposition. The film suggests that had history taken a different turn, Saladin might have remained a talented but obscure general. His path to power was paved by nepotism and opportunity; he rose under the tutelage of his uncle, Shirkuh, a seasoned general who led military expeditions into Fatimid Egypt.

The Egyptian Crucible and the Death of Shirkuh

The documentary identifies Egypt as the crucible of Saladin’s ambition. The death of his uncle Shirkuh—attributed to overeating, a detail that adds a touch of grotesque realism to the high politics of the era—created a power vacuum that the young Saladin stepped into. This transition marked the beginning of his true political career. No longer a subordinate, he took command of Egypt, a wealthy and strategic province that would serve as the economic engine for his future campaigns. The narrative highlights that Saladin’s rise was not greeted with universal acclaim; he was a Sunni Kurd ruling over a Shi’a Fatimid population, a precarious position that required both diplomatic finesse and an iron fist.

However, the acquisition of Egypt was not the culmination of his ambition but the prologue. The documentary details a “decade of war” that followed, but strikingly, these wars were not initially against the Christian Crusaders. Instead, Saladin spent ten years fighting his Muslim neighbors. This period of consolidation was essential. To confront the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Saladin needed to unify the fractured Islamic polity. He systematically dismantled the rivalries between Damascus, Aleppo, and Mosul, effectively surrounding the Crusader states with a unified Ayyubid empire. This underscores a critical strategic axiom presented in the film: internal unity is the prerequisite for external conquest. The documentary frames these early wars not as naked aggression, but as a necessary “Jihad of the Sword” against discord (fitna) within the Ummah, setting the stage for the greater Jihad against the Franks.

The Revelation of 1185: The Psychological Pivot

A pivotal psychological turning point is identified in the year 1185. The documentary describes Saladin falling gravely ill, a near-death experience that fundamentally altered his worldview. It was during this convalescence that the secular conqueror transformed into the pious mujahid. The film posits that Saladin interpreted his survival as divine intervention, a sign that God had spared him for a specific purpose: the liberation of Jerusalem.

This revelation catalyzed a shift in his rhetoric and strategy. He began to champion the concept of Jihad—defined here as a righteous struggle—not merely as a military tool but as a spiritual imperative to unite the Muslim world against the “infidels”. The documentary suggests that this religious awakening was the final piece of the puzzle, providing the ideological glue to hold his diverse coalition of Kurds, Turks, and Arabs together. The man who had spent his youth playing polo and his middle years fighting Muslims now turned his gaze exclusively toward the Holy City, driven by a desire to atone for his past sins through the mechanism of holy war. This period marks the transition of Saladin from a Realpolitik strategist to a charismatic religious leader, a duality that would define his interaction with the West.

Part II: The Collapse of the Latin Kingdom

The Strategic Landscape of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, held by the “Franks” (a catch-all term for Western European Crusaders), is depicted as a fragile island in a rising Islamic sea. By 1187, the strategic situation had become dire. The documentary portrays the Crusader leadership as deeply divided and prone to catastrophic errors in judgment. The “Knights of the Kingdom of Jerusalem” and the “occupying Franks” are shown living under the constant shadow of the unified Islamic force gathering on their borders. The film notes that the Franks took the “terrifying decision to fight Saladin alone,” implying a failure to secure support from Europe in time or a hubristic belief in their own invincibility.

While the documentary focuses on the collective failure of the Franks, it notably omits specific mentions of key antagonists like Reynald of Châtillon or King Guy of Lusignan by name. This narrative choice streamlines the conflict into a binary struggle between Saladin and the abstract concept of “Frankish power,” rather than getting bogged down in the complex feudal politics of the Latin East. However, the presence of the True Cross—a relic believed to contain fragments of the cross upon which Christ died—is highlighted as a totem of their faith, carried into battle to guarantee victory. The documentary treats this reliance on relics as a symptom of their desperation rather than a strategic asset, foreshadowing the spiritual crisis that would follow their defeat.

The Battle of Hattin (1187): The Anatomy of a Disaster

The narrative reaches a crescendo with the Battle of Hattin, presented as the masterstroke of Saladin’s military career and the death knell of the Crusader Kingdom. The documentary details how Saladin utilized the terrain and the climate as weapons of war. He lured the Christian army away from their water sources at Saffuriya and into the arid, waterless hills of Hattin. The description of the battle emphasizes the physical misery of the Crusaders: dehydrated, surrounded, and subjected to the relentless heat of the Palestinian summer, they were effectively defeated before the first sword was swung.

Saladin’s tactics are described as “cunningly cruel” yet brilliant. By setting fire to the dry brush surrounding the Crusader camp, he utilized smoke and heat to further torment the trapped enemy, creating a literal hell on earth for the armored knights. The result was total annihilation. The documentary states that Saladin “slaughtered the bulk of their army” and, crucially, captured the True Cross. This loss was not just military; it was a theological catastrophe for Christendom. The capture of the Cross symbolized the withdrawal of divine favor from the Crusader kingdom and the validation of Saladin’s claim to be the sword of God. The film captures the magnitude of this event: thousands of Christian knights were killed or captured, leaving the castles and cities of the kingdom stripped of their defenders.

The Conquest of Jerusalem and the Ethics of Victory

Following Hattin, the road to Jerusalem lay open. The siege of the city in October 1187 is presented as a moment of profound historical symmetry and contrast. The documentary explicitly juxtaposes Saladin’s entry into Jerusalem with the events of the First Crusade in 1099. It recounts how, eighty-eight years prior, the Crusaders had “slaughtered every living thing” in the city, creating a bloodbath intended to terrorize the region. The film describes the terror within the walls in 1187; mothers hacking off their hair in mourning and monks hiding icons, convinced that the Muslims would exact a retributive “eye for an eye” punishment.

However, Saladin’s actions are portrayed as a deliberate subversion of this expectation. The documentary emphasizes his decision to show mercy. Instead of a massacre, he negotiated the surrender of the city, allowing the Christian population to ransom themselves or leave safely. He explicitly “banned the killing” of civilians, a command that the film frames as a moral victory superior even to his military triumph at Hattin. The purification of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque with rose water serves as a powerful visual symbol in the narrative. It represents the cleansing of the city not through blood, as the Crusaders had done, but through a ritual of beauty and scent.

This act of mercy is analyzed as both a moral choice and a strategic one. By sparing the Christians, Saladin avoided a desperate last stand that might have damaged the holy sites. Moreover, it cemented his reputation as a “chivalrous” leader, a man who possessed a nobility of spirit that stunned his enemies. The documentary argues that this mercy was calculated to demonstrate the superiority of Islamic ethics over the barbarism of the Frankish invaders, a theme that resonates through the subsequent centuries of historiography.

Part III: The Lion from the West

The Response of Europe: The Wrath of the Angevin

The fall of Jerusalem sent shockwaves through Christendom, prompting the Third Crusade. It is here that the documentary introduces the antagonist-cum-co-protagonist: Richard I of England, known as the Lionheart. Richard is introduced with superlatives: “Europe’s finest warrior,” a prince of the vast Angevin empire that controlled England and northern France. The film establishes his pedigree, noting that his great-grandfather, Fulk of Anjou, had once been King of the Holy City, establishing a dynastic claim to the land he sought to reconquer. This genealogical detail adds a personal dimension to Richard’s crusade; he is not just fighting for God, but for his family’s legacy.

Richard is portrayed as the mirror image of Saladin: equally brilliant in war but contrasting in temperament. Where Saladin is depicted as patient, pious, and politically astute, Richard is shown as ferocious, arrogant, and technically unmatched in combat. The documentary suggests that while Saladin fought for a religious ideal and the unification of his people, Richard fought for glory, patrimony, and the sheer love of battle. This duality sets the stage for a conflict that is as much about personality as it is about politics.

The Siege of Acre: The Game Changer

The narrative moves to the coast, specifically the Siege of Acre, which becomes the first major test of wills between the two leaders. The documentary describes the siege as a brutal stalemate that had dragged on for nearly two years before Richard’s arrival. His entry into the theater of war changed the dynamic instantly. The pressure he applied to the city’s defenders—through the use of superior siege engines and sheer force of will—forced a surrender, a victory that Saladin had desperately tried to prevent.

The aftermath of the Siege of Acre provides the darkest chapter in the documentary’s portrayal of Richard. It details the incident of the 3,000 Muslim prisoners. Frustrated by stalled negotiations over the return of the True Cross and payment of ransoms, and eager to march on Jerusalem, Richard ordered the mass execution of these prisoners in full view of Saladin’s army. The documentary does not shy away from the brutality of this act, describing it as a violation of the norms of the time, which favored ransom over slaughter.

This event serves a dual narrative purpose. First, it demonstrates Richard’s ruthlessness and his prioritization of military expediency over humanity. He “felt Saladin gave him no choice,” the narrator suggests, implying that Richard viewed the prisoners as a logistical burden that would slow his march. Second, it heightens the moral contrast with Saladin, recalling the earlier juxtaposition of the 1099 massacre with the 1187 peaceful entry. Richard is firmly placed in the tradition of the violent Frankish conqueror, despite his personal bravery. The execution is portrayed as a cold, calculated act of terror, contrasting sharply with Saladin’s emotional restraint.

The Battle of Arsuf: The Limits of Invincibility

The war then shifts to the open field at the Battle of Arsuf (1191). Here, the documentary illustrates the clash of tactics: the mobile, harassment-based warfare of Saladin’s light cavalry against the disciplined, armored charge of Richard’s knights. Saladin attempted to break the Crusader column as it marched south to Jaffa, hoping to goad them into a premature charge that would separate their infantry from their cavalry. However, Richard’s discipline held the army together until the perfect moment. The film describes Richard’s counter-attack as a ferocious unleashing of pent-up aggression that shattered the Muslim lines.

This defeat at Arsuf is significant in the narrative because it punctures the aura of Saladin’s invincibility. It proves that Richard was the superior field tactician, capable of defeating the man who had united the East. However, the documentary is careful to note that while Richard won the battle, he could not win the war. The “stalemate” becomes the defining theme of the latter half of the film. Saladin, though defeated in battle, maintained his strategic grip on the ultimate prize: Jerusalem itself. He adopted a scorched-earth policy, destroying the wells and fortifications around the Holy City to make a siege logistically impossible for the Crusaders.

Part IV: Diplomacy, Disease, and Death

The Unmet Rivals and the Marriage Proposal

A recurring theme in the documentary is the personal distance between the two protagonists. Despite their names being forever linked in history, the film clarifies that Saladin and Richard “never personally met”. Their relationship was conducted entirely through intermediaries and correspondence. This physical absence adds a layer of mythic tragedy to their rivalry; they were intimate enemies who never looked one another in the eye.

The primary conduit for this diplomacy was Saladin’s brother, Al-Adil (known to the Franks as Saphadin). The documentary highlights the rapport between Richard and Al-Adil, which went so far that Richard proposed a shocking diplomatic solution: a marriage alliance. Richard suggested that Al-Adil should marry his sister, Joanna (Queen of Sicily), and that the couple should “jointly share the kingdom of Jerusalem”. This proposal, while never enacted due to religious objections from both sides, highlights the pragmatism that existed alongside the religious fanaticism of the Crusades. It suggests a world where interfaith marriage and shared sovereignty were conceivable solutions to the holy war, challenging the modern narrative of eternal, irreconcilable conflict.

Chivalry Across the Lines: Fruit and Ice

The documentary emphasizes moments of chivalry that punctuated the violence. When Richard fell ill (likely with scurvy or a similar camp disease), Saladin sent him gifts of “fruit and ice” (snow from Mount Hermon) to cool his fever. This gesture is interpreted not as weakness, but as a supreme display of confidence and honor. Saladin refused to meet Richard while they were at war because he considered it dishonorable to socialize with a man he intended to kill, yet he would not let his enemy perish from sickness or thirst. This nuanced code of ethics is central to the documentary’s portrait of Saladin as a “virtuous pagan” whom Europeans could admire. It suggests that Saladin viewed Richard as a worthy peer, deserving of respect even in the midst of a war for survival.

The Treaty of Jaffa and the End of the Crusade

Ultimately, the Third Crusade ended not with a decisive battle but with a treaty. The Treaty of Jaffa (1192) solidified the status quo: the Crusaders would keep the coastal cities they had conquered (from Tyre to Jaffa), ensuring the survival of a diminished Latin Kingdom, but Jerusalem would remain in Muslim hands. The documentary frames this as a strategic victory for Saladin. He had successfully defended the Holy City against the greatest warrior of Christendom. Richard, despite his tactical victories, was forced to return to Europe to save his throne from his brother John and the King of France.

However, the cost of this victory was high. The film describes Saladin as exhausted, his authority “on the verge of collapse” due to the strains of the prolonged campaign and the dissatisfaction of his emirs who had been in the saddle for years. The peace treaty was a necessity for survival, not just a diplomatic preference.

The Death of a Hero

The narrative concludes with the death of Saladin in 1193, merely six months after the signing of the treaty. He was 56 years old. The documentary attributes his death to the sheer physical and mental toll of the Crusade. He had spent himself entirely in the defense of his faith. The film touches upon the modesty of his end. It does not explicitly state he died penniless (a common legend), but it emphasizes the spiritual richness of his legacy over material wealth. He is eulogized as a man who “redefined the rules of medieval warfare” and whose “legacy is with us even today,” symbolizing virtue, magnanimity, and generosity.

Part V: Thematic Epilogue: The Shadow of the Sultan

The legacy of Yusuf ibn Ayyub extends far beyond the dry stone walls of Jerusalem or the dusty plains of Hattin. As the documentary concludes, he remains “the most famous Muslim in the whole world after the prophet Muhammad”. However, the nature of this fame is complex, bifurcated between his image in the West and his utilization in the East. This epilogue embellishes the documentary’s narrative by exploring the “Second Life” of Saladin in modern memory.

The Western Construct: The Virtuous Pagan

In the Western imagination, Saladin has occupied a unique space since the medieval era. Dante Alighieri placed him in Limbo alongside Hector and Aeneas, designating him a “virtuous pagan”—a man who, though not Christian, possessed such immense moral rectitude that he was exempt from the torments of Hell. The documentary reinforces this tradition. By focusing on the gifts of ice, the mercy at Jerusalem, and the respect for Richard, the film caters to a Eurocentric desire to find a “worthy opponent.” Saladin validates the Crusades; he makes the struggle noble because the enemy was noble. If Richard had fought a barbarian, the glory of the Third Crusade would be diminished. By fighting Saladin, Richard’s own legend is elevated. Thus, the Western Saladin is a reflection of Western anxieties and ideals about war, honor, and the “Other.”

The Eastern Construct: The Unifier and the Liberator (The Saddam Connection)

In the Middle East, Saladin’s legacy has undergone significant transformation, particularly in the 20th and 21st centuries. The documentary’s mention of Tikrit as the birthplace of both Saladin and Saddam Hussein is the tip of a massive ideological iceberg. Saddam Hussein actively weaponized this coincidence. As noted in the supplementary research, Saddam instigated a “monumental personality cult,” identifying himself as Saladin Reincarnated.

During the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf Wars, Saddam drew explicit parallels between his conflicts and the Crusades. He portrayed the Iranians as the “Persians” (whom Saladin’s predecessors fought) and the American coalition as the new “Crusaders” (the Franks). He commissioned postage stamps showing his face alongside Saladin’s and rebuilt Saladin’s birthplace in Tikrit to physically cement the lineage. This appropriation served a specific political purpose: to frame Saddam not as a secular dictator, but as the heir to a Pan-Arab, Islamic tradition of resistance against foreign invasion.

Furthermore, the documentary’s focus on Saladin’s “Jihad to unite” resonates with the ideology of Pan-Arabism championed by Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt in the 1950s and 60s. Nasser, like Saladin, ruled from Cairo and sought to unify Egypt and Syria (the United Arab Republic) to confront a perceived Western outpost (Israel). For Nasser and his ideologues, Saladin was the historical blueprint for Arab unity. The film’s emphasis on the “decade of war” against Muslim rivals to achieve unity mirrors the modern argument that internal dissent must be crushed to face the external enemy.

The Burden of History

The final insight offered by the documentary and the surrounding discourse is the inescapability of the Crusades in modern geopolitical rhetoric. The film notes that the struggle between Richard and Saladin “set the tone for religious conflict for centuries to come”. The terminology of the 12th century—Crusade, Jihad, Infidel, Martyr—remains in the lexicon of the 21st.

The documentary, therefore, is not just a biography of a dead Sultan. It is an origin story for the fault lines of the modern world. It suggests that the “generosity and magnanimity” of Saladin are not just historical footnotes, but desperate requirements for a region still trapped in the cycles of violence that he and Richard helped to define. The tragedy of Saladin, as presented, is that his greatest victory—the recapture of Jerusalem—did not bring peace, but rather ensured that the city would remain a contested focal point of human aspiration and violence for another millennium.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Historical Events in the Documentary

| Event | Year | Saladin’s Role (Documentary Portrayal) | Richard’s Role (Documentary Portrayal) | Outcome/Significance |

| Rise to Power | 1169-1174 | Inherited command from Uncle Shirkuh; unified Egypt and Syria. | N/A (Richard is in Europe). | Creation of a unified Ayyubid state surrounding the Crusaders. |

| Battle of Hattin | 1187 | Tactical genius; lured Franks into waterless hills; captured True Cross. | N/A | Destruction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s field army. |

| Conquest of Jerusalem | 1187 | Merciful Conqueror; refused to massacre Christians; purified city with rosewater. | N/A | Restoration of Islamic rule in the Holy City; spark for Third Crusade. |

| Siege of Acre | 1189-1191 | Attempted to break the siege but failed; forced to accept surrender. | The Game Changer; arrival forced capitulation; executed 3,000 prisoners. | Crusader foothold re-established; moral stain on Richard. |

| Battle of Arsuf | 1191 | Attempted ambush failed; suffered tactical defeat. | Tactical Brilliance; led a devastating heavy cavalry charge. | Proved Richard’s military superiority in open battle; halted Saladin’s aura of invincibility. |

| Treaty of Jaffa | 1192 | Pragmatist; agreed to partition of land to save Jerusalem. | Pragmatist; realized Jerusalem could not be held; secured coast. | End of Third Crusade; status quo established (Muslim Jerusalem, Christian Coast). |

Table 2: Thematic Contrast of Leadership Styles

| Theme | Saladin (The Sultan) | Richard I (The Lionheart) |

| Motivation | Religious atonement; Jihad; Defense of Islam. | Glory; Patrimony; Religious duty (Crusader oath). |

| Tactics | Mobility; harassment; utilization of terrain/climate (Hattin). | Shock warfare; discipline; logistical mastery; amphibious assaults (Acre). |

| Ethics of War | Restraint; mercy to captives (Jerusalem); generosity (gifts to Richard). | Total War; utility of terror (massacre at Acre); chivalric but ruthless. |

| Legacy | The Virtuous Unifier; symbol of Islamic dignity. | The Warrior King; symbol of European martial valor. |

Table 3: Modern Political Appropriations of Saladin (Thematic Epilogue Context)

| Figure/Movement | Connection to Saladin | Purpose of Appropriation |

| Saddam Hussein | Shared birthplace (Tikrit); Commissioned stamps/murals merging their faces. | To legitimize authority; to frame the Iran-Iraq war and conflicts with the West as a continuation of Saladin’s defense against “Persians” and “Crusaders.” |

| Pan-Arabism (Nasser) | Saladin as the Unifier of Egypt and Syria. | To promote the United Arab Republic (UAR); emphasizing secular unity over religious identity. |

| Western Romanticism | “The Virtuous Pagan” (Dante, Scott). | To critique contemporary Western morality; to romanticize the “Orient”; to validate the Crusades as a noble contest. |

Conclusion

The BBC’s The Third Crusade: Saladin & Richard the Lionheart provides a compelling, if narratively streamlined, account of one of history’s most dramatic rivalries. By centering the narrative on the personal virtues and strategic decisions of its two protagonists, it elevates the Third Crusade from a chaotic medieval slaughter to a tragic epic of honor and faith. The documentary successfully argues that Saladin’s greatness lay not merely in his conquest of territory, but in his conquest of the moral high ground—a victory that has ensured his name endures not just in the history books of the East, but in the legends of the West. Through the lens of this film, we understand that while Richard may have won the battles at Acre and Arsuf, Saladin won the war for history’s memory.

Leave a comment