Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

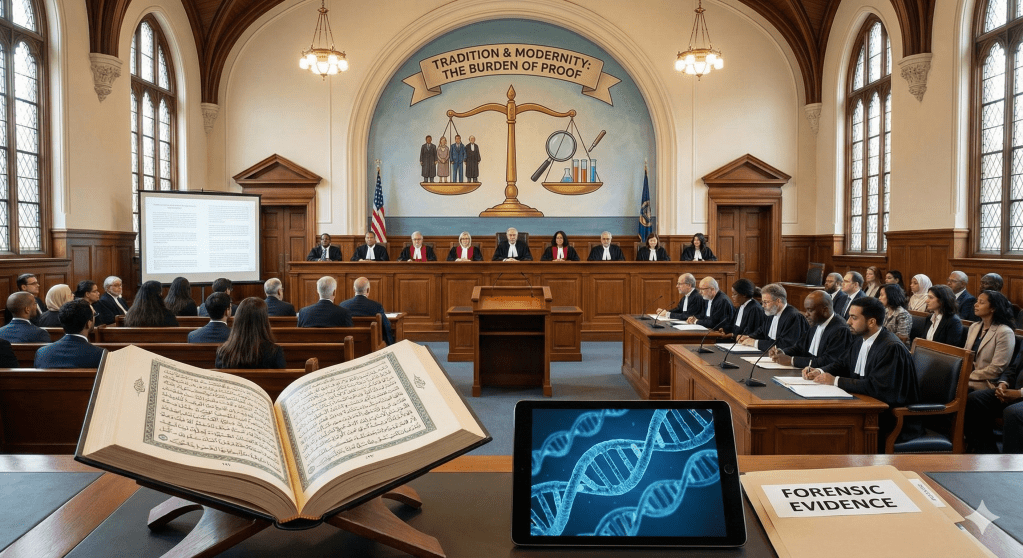

This extensive research report provides a dual-layered analysis: first, a granular critical review of the Pakistani television drama Case No. 9, produced by 7th Sky Entertainment, and second, a theological and legal dissertation arguing for the reinterpretation of the Quranic “four-witness” requirement in the context of modern forensic science. The report posits that the 7th-century injunction requiring four male eyewitnesses to prove Zina (adultery) was a socio-legal mechanism designed to protect privacy (Satr) and prevent slander (Qadhf) in an era reliant solely on oral testimony. However, the application of this standard to Zina-bil-Jabar (rape) in the contemporary era constitutes a miscarriage of justice that violates the Maqasid al-Shariah (Objectives of Law). Through a detailed deconstruction of Case No. 9‘s narrative arc—from the linguistic erasure of the victim in the First Information Report (FIR) to the reliance on CCTV footage as a deus ex machina—this document demonstrates how the drama serves as a cultural proxy for a broader legal debate. It integrates classical Islamic jurisprudence, the history of Pakistan’s Hudood Ordinances, and modern forensic capabilities (DNA profiling) to argue that the “essence” of the four-witness rule—certainty (Yaqin)—is now best fulfilled by scientific evidence. The report concludes that while the four-witness rule remains applicable to consensual acts to preserve privacy, it must be decoupled from criminal sexual violence, where forensic science serves as the “silent witness” of truth.

Chapter 1: The Cultural Phenomenon of Case No. 9 — A Narrative and Production Analysis

1.1 Production Context and the Shift in Pakistani Melodrama

In the crowded landscape of Pakistani television, dominated by the domestic politics of the saas-bahu (mother-in-law/daughter-in-law) dynamic, Case No. 9 emerged as a significant deviation from the norm. Produced under the banner of 7th Sky Entertainment by industry stalwarts Abdullah Kadwani and Asad Qureshi, the drama represents a strategic pivot toward “narratives of resistance”.1 While the production house is historically known for high-octane melodramas that often reinforce traditional gender roles, Case No. 9 utilizes the same high-production value to subvert these tropes, presenting a story that functions as both a thriller and a legal procedural.

The drama aired on Har Pal Geo (Geo TV), a channel with massive reach in Pakistan, ensuring that its message penetrated not just the urban liberal elite but the rural heartlands where traditional notions of honor and justice often prevail.1 Directed by Syed Wajahat Hussain, whose previous works include the spiritually charged Khuda Aur Mohabbat 3 and the revenge saga Khaie, the direction in Case No. 9 employs a distinct visual language. Hussain moves away from the warm, soft-focus aesthetics of romance to a colder, clinical palette, particularly in the police station and courtroom scenes, emphasizing the harsh reality of the legal system.2

1.2 The Writer as Auteur: Shahzeb Khanzada’s Script

A critical factor in the drama’s unique tonal quality is its writer, Shahzeb Khanzada. Primarily known as a hard-hitting journalist and current affairs anchor, Khanzada’s transition to screenwriting brought a level of procedural, almost documentary-like rigor to the script.1 The dialogue often eschews poetic Urdu metaphors for sharp, legalistic precision, mirroring the arguments one might hear in a high-stakes investigation rather than a soap opera.

Khanzada’s script does not merely tell a story; it interrogates the system. Critics and viewers noted that the drama often felt like a “public service announcement” (PSA) woven into a narrative, using terms and legal concepts rarely discussed on prime-time television.3 The script meticulously highlights procedural lapses—such as the delay in filing the First Information Report (FIR) and the manipulation of witness statements—serving to educate the public on their legal rights while simultaneously entertaining them.

1.3 Cast Dynamics and Character Archetypes

1.3.1 Sehar Moazzam: The “Survivor” not the “Victim”

Saba Qamar, playing the protagonist Sehar Moazzam, delivers a performance that anchors the entire series. Qamar, known for her roles in Hindi Medium and Baaghi, brings a gravitas that elevates Sehar beyond the typical “weeping woman” (roti-dhoti aurat) archetype.4

Sehar is depicted as a nuanced figure: a divorced woman, a breadwinner, and a professional. This characterization is deliberate. By making Sehar a divorcee, the script challenges the societal stigma that views divorced women as “damaged goods” or sexually available. Sehar’s journey is one of reclaiming agency. She corrects the terminology used around her, insisting on being called a “rape survivor” rather than a “victim”.4 This linguistic shift is crucial; it reframes her status from one of passive suffering to active resistance.

1.3.2 Kamran: The Anatomy of Privilege

Faysal Quraishi portrays the antagonist, Kamran, with a disturbing calmness that critics have described as “terrifyingly convincing”.2 Kamran is not a mustache-twirling villain; he is a wealthy, respected businessman who believes his status places him above the law. He embodies the “banality of evil”—a monster who wears a respectable face.

Quraishi’s performance highlights the psychological profile of a predator who rationalizes his actions. His dialogue, particularly the line, “It’s a shortcut to accuse a rich man of rape and get rich,” encapsulates the misogynistic defense strategies often employed in real-world courts to discredit accusers.2 This portrayal forces the audience to confront the reality that sexual violence is often perpetrated by powerful men who leverage their social capital to silence victims.

1.3.3 The Supporting Pillars: Beenish Ali and Manisha

The drama is notable for its strong female supporting cast, which allows it to pass the Bechdel Test—a rarity in Pakistani media.4 Aamina Sheikh, making a comeback after seven years, plays Barrister Beenish Ali, the prosecutor. Her performance is characterized by “nerves of steel” and calm authority, contrasting with the histrionics of the defense counsel.5 Beenish serves as the voice of modern legal interpretation, challenging archaic patriarchal norms within the courtroom.

Naveen Waqar plays Manisha, a women’s rights activist and the wife of Sehar’s colleague, Rohit/Mohit. Manisha represents the “ally” figure. She is crucial to the plot, not only providing emotional support but also holding the men in her life accountable. She pressures her husband to testify, prioritizing justice over marital harmony, thereby subverting the traditional expectation of a wife’s blind obedience.4

1.4 Narrative Deconstruction: From Crime to Courtroom

1.4.1 The Incident and the Erasure of Agency

The narrative begins by establishing Sehar’s competence and ambition, which Kamran views as a challenge to his ego. The assault itself is handled with sensitivity but does not shy away from the brutality of the violation. The immediate aftermath focuses on the procedural violence inflicted by the state. Sehar is prevented from getting a medical exam due to “family pressure and societal stigma,” a common barrier in Pakistan where “honor” is prioritized over justice.2

A profound insight drawn from the research material is the linguistic analysis of the FIR. The script depicts how the police, led by the corrupt Inspector Shafeeq (Gohar Rasheed), manipulate Sehar’s statement. An active voice declaration like “I stopped him” is converted into the passive “he was stopped” in the written report.6 This grammatical shift is a form of legal violence, stripping the survivor of agency and introducing ambiguity that defense lawyers can later exploit. Inspector Shafeeq’s corruption—delaying the FIR for a week and accepting bribes—represents the compromised “chain of custody” that often dooms rape cases before they reach trial.2

1.4.2 The Courtroom Battle: Law vs. Misogyny

The courtroom scenes act as the ideological battleground of the drama. The defense attorney, Bukhari Sahab (Noor-ul-Hassan), employs classic victim-blaming tactics. He questions Sehar’s character, her divorce, and her late working hours, implying that her lifestyle invited the assault.4

Barrister Beenish counters these arguments by anchoring the case in constitutional law and modern rights. She argues that Sehar’s past—whether she is married, divorced, or sexually active—is legally irrelevant to the charge of rape. This argument mirrors the provisions of the Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Act 2021, which prohibits the “two-finger test” and the use of a victim’s sexual history to discredit her testimony.7

1.4.3 The “Silent Witness” and the Finale

The climax of the drama hinges on the failure of human testimony and the triumph of digital evidence. With witnesses intimidated or compromised, the case seems lost until Kiran (Rushna Khan) discovers deleted CCTV footage.2 This footage serves as the objective, irrefutable proof—the “silent witness” that cannot be bribed.

The finale sees Kamran sentenced to 25 years of rigorous imprisonment.9 While this provides a cathartic resolution for the audience, critics noted that the reliance on CCTV footage was a “convenient” plot device.2 In the real world, most rapes occur in private spaces devoid of cameras. This narrative choice inadvertently highlights the central legal problem: without the “camera” (the modern eye), how does one meet the burden of proof?

1.5 Reception, Censorship, and the 26th Amendment

Case No. 9 generated significant discourse on social media platforms like Reddit, with users praising it as a “must-watch” for its educational content.3 However, it also faced state censorship.

In Episode 17, a scene featuring Barrister Beenish citing a judgment by Justice Mansoor Ali Shah and referencing the 26th Constitutional Amendment was aired on TV but removed from the YouTube upload.11 In the unedited scene, Beenish remarks, “Had the 26th Constitutional Amendment not been passed… he would have been our country’s chief justice.” This line was a direct political commentary on the amendment, which altered the seniority rules for judicial appointments. The removal of this scene underscores the tension between the drama’s realistic legal portrayal and the political sensitivities of the Pakistani state. It also highlights the “meta” layer of the show: just as truth is suppressed in the drama’s police station, political truth is suppressed in the drama’s distribution.11

Chapter 2: The Screaming Silence — The 7th Century Context and the “Impossible” Standard

To understand why the legal battle in Case No. 9 is so arduous, one must examine the theological roots of the evidentiary laws that underpin Pakistan’s legal consciousness. The requirement of four witnesses is not arbitrary; it is rooted in the specific socio-political context of 7th-century Arabia.

2.1 The Sociology of Privacy (Satr) in Tribal Arabia

In 7th-century Madinah, the concept of privacy (Satr) was physically and socially fragile. Homes were often single-room structures made of palm fronds and mud, and communal living was the norm.13 In such an environment, private intimacies were easily overheard or glimpsed.

The Quranic injunction regarding four witnesses was revealed to raise the bar for public accusations. The goal was to make it impossible to prove consensual adultery unless the act was so flagrant that it constituted a public rebellion against decency (Fahisha). If four upright men could testify to seeing the act “like a kohl stick in a kohl container” (a classical metaphor for penetration), it meant the couple had engaged in sex effectively in public.13 Thus, the law was a privacy shield: it told the community, “Unless you see it with your own eyes in a group, do not speak of it.”

2.2 The Incident of Ifk (The Slander)

The specific occasion of revelation (Asbab al-Nuzul) for the four-witness rule (Surah An-Nur, 24:4) was the Incident of Ifk, where Aisha (RA), the wife of the Prophet (PBUH), was separated from her caravan and returned escorted by a unrelated man, Safwan ibn Muattal. Hypocrites in the community spread rumors of infidelity.14

God revealed the verse to punish the slanderers, not to protect adulterers. The verse mandates:

“And those who accuse chaste women and then do not produce four witnesses – flog them with eighty lashes…” (Quran 24:4)

This established the crime of Qadhf (slander). The requirement for four witnesses was a protective mechanism for women against baseless rumors. It was a burden of proof placed on the accuser to stop loose talk. It was never intended to be a burden placed on a victim of violence to prove her trauma.14

2.3 Classical Jurisprudence: Hadd vs. Tazir

Classical Islamic scholars (Jurists/Fuqaha) of the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali schools codified this into a dual-layered system:

| Legal Category | Definition | Standard of Proof | Punishment |

| Hadd (Limit) | Crimes against God (e.g., Adultery, Theft). Fixed punishments. | Absolute Certainty: 4 Male Eyewitnesses or 4 Confessions. | Stoning (married) or Lashing (unmarried). |

| Tazir (Discretion) | Crimes against Society/Individuals. Discretionary punishments. | Probable Cause: Circumstantial evidence (Qarinah), fewer witnesses, judge’s intuition. | Imprisonment, Fines, Lashing (at judge’s discretion). |

Historically, if a woman claimed rape but could not produce four witnesses, the judge could still punish the rapist under Tazir if there was circumstantial evidence (bruises, torn clothes, pregnancy).13 The four-witness rule was strictly for the maximum punishment of Hadd. It was not a “get out of jail free” card for rapists, although it was often misinterpreted as such in later periods.16

Chapter 3: The Weaponization of Law — From Protection to Persecution

The theological nuance of the 7th century was lost in the 20th-century legislative experiments of Pakistan, specifically under the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq.

3.1 The Hudood Ordinances of 1979

In 1979, the military government promulgated the Hudood Ordinances to “Islamize” the penal code. The fatal flaw of this legislation was the conflation of Zina (consensual adultery) with Zina-bil-Jabar (rape).17

Under this law, the distinction between a crime of morality (consensual) and a crime of violence (forced) was blurred. If a rape victim reported the crime (thereby admitting that sexual intercourse took place) but failed to produce four righteous male eyewitnesses to prove coercion, the court could—and often did—treat her admission of intercourse as a confession of adultery. Consequently, victims were imprisoned or lashed for Zina while the rapists walked free due to “lack of evidence”.17 This effectively weaponized Surah An-Nur against the very women it was meant to protect.

3.2 The Resistance of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII)

The Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), a constitutional advisory body, has historically maintained a rigid stance on this issue. As recently as 2013, the CII Chairman, Maulana Sherani, declared that DNA evidence could not be used as “primary evidence” in rape cases.19 His argument was theological literalism: “The words of Allah are perfect while science is always improving”.19

The CII argued that DNA could only be used as “supporting evidence” (Qarinah). If four witnesses were not present, the Hadd punishment could not be awarded, regardless of what the DNA said. This stance created a legal absurdity where a rapist identified by DNA could not receive the maximum penalty mandated by Sharia, but only a lesser Tazir sentence.20

3.3 Legislative Evolution: The Road to Reform

Civil society, women’s rights activists (like the character Manisha in Case No. 9), and legal reformers fought back against this interpretation.

- The Women’s Protection Act (2006): This landmark legislation returned rape to the Pakistan Penal Code (civil law), separating it from the Hudood Ordinance. It removed the four-witness requirement for rape, allowing convictions based on forensic and circumstantial evidence.21

- The Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Act 2021: Triggered by high-profile cases (like the Motorway Rape Case), this act mandated the use of modern forensic investigation methods, established special courts, and prohibited the “two-finger test.” It explicitly recognized DNA and modern forensics as critical to the investigation process.7

Despite these laws, the cultural mindset—represented by Kamran’s defense in Case No. 9—often lags behind. Defense lawyers still argue that without eyewitnesses, “doubt” exists, and in Islamic law, “doubt wards off the Hadd punishment” (Idra’u al-hudud bi-l-shubuhat).

Chapter 4: The Scientific Witness — Redefining Bayyinah and Qarinah

This report argues that the solution to the “witness dilemma” lies in redefining what constitutes a “witness” in the eyes of Sharia.

4.1 The Concept of Bayyinah (Clear Proof)

In the Quran, the term used for evidence is often Bayyinah—meaning “clear proof” or “that which makes the truth manifest.” While classical jurists often interpreted Bayyinah strictly as oral testimony (Shahadah), modern reformist scholars argue that Bayyinah is an umbrella term for any proof that establishes certainty.22

If the objective is to establish the truth of the crime, then a DNA profile, which has a probability of error of less than 1 in a billion, is a far more “clear proof” than the testimony of four men who may be myopic, bribed, or forgetful.24

4.2 DNA as Qarinah Qat’iyyah (Definitive Circumstantial Evidence)

Islamic jurisprudence classifies circumstantial evidence (Qarinah) into two types:

- Qarinah Zanniyyah (Speculative): Evidence that suggests a probability but not certainty (e.g., being seen near the crime scene).

- Qarinah Qat’iyyah (Definitive): Evidence that leads to absolute certainty (Yaqin).

Classical scholars accepted pregnancy as Qarinah Qat’iyyah for unlawful intercourse (in the absence of a husband). Modern jurists argue that DNA profiling and CCTV footage should be elevated to the status of Qarinah Qat’iyyah. Since they provide a level of certainty equal to or greater than eyewitness testimony, they should be sufficient to ground not just Tazir but even Hadd punishments.24

In Case No. 9, the CCTV footage acts as Qarinah Qat’iyyah. Once it is viewed, no reasonable doubt remains. The “silent witness” speaks louder than any human.

4.3 The Hirabah Argument: Reclassifying Rape

A potent theological argument, championed by scholars like Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, is that rape should not be prosecuted as Zina at all.

- Zina is a crime of morality involving consent.

- Rape is a crime of violence and power.

Ghamidi argues that rape falls under the category of Hirabah (brigandage/war against society) or Fasad-fil-Ardh (corruption in the land).26

- The Evidence Implication: The Quran requires four witnesses only for Zina. It does not require four witnesses for Hirabah (violent assault). For Hirabah, the standard of proof is the general standard for any crime—whatever convinces the judge.

- The Punishment Implication: The punishments for Hirabah (Surah Al-Ma’idah 5:33) are severe (execution, crucifixion, exile) and give the state broad powers to punish the offender.

By reclassifying rape as Hirabah, the entire theological obstacle of “four witnesses” evaporates. The state can use DNA, CCTV, and medical reports to convict the rapist as a violent criminal without violating the sanctity of the Zina laws.27

Chapter 5: Case No. 9 as Legal Jurisprudence and Social Commentary

The drama Case No. 9 serves as a fictional testing ground for these legal theories.

5.1 The Argument of Barrister Beenish Ali

In the courtroom, Beenish Ali (Aamina Sheikh) effectively employs the Hirabah logic, even if she uses secular legal terms. She focuses on the violence and the lack of consent. When she dismantles the defense’s focus on Sehar’s character, she is implicitly arguing that this is not a trial of morality (Zina); it is a trial of assault.

Her reference to Justice Ayesha Malik—who outlawed the “two-finger test” in a historic 2021 judgment—anchors the drama in real-world legal victories. Justice Malik’s ruling was based on the premise that a woman’s virginity is irrelevant to the fact of rape, a concept Beenish reiterates forcefully.12

5.2 The “Witness” of Modernity

The turning point in the drama is the discovery of the CCTV footage by Kiran. This plot device highlights the fragility of justice in the absence of technology. In the “essence” argument, the CCTV camera is the modern equivalent of the four righteous witnesses.

- It is impartial (Righteous/Adl).

- It records the event exactly as it happened (Accuracy/Dabt).

- It is multiple (often multiple angles/cameras).

The drama suggests that denying this evidence would be an act of injustice (Zulm). If the Sharia intends to establish truth, ignoring the CCTV footage would be un-Islamic.

5.3 The Final Verdict and its Implications

Kamran is sentenced to 25 years. This is a significant specific detail. It likely corresponds to the punishment for rape under Section 376 of the Pakistan Penal Code, which allows for death or imprisonment of not less than ten years or twenty-five years.9

The meta-narrative provided by the actors adds another layer. Saba Qamar, in her post-finale statement, wrote, “I have won both cases — Case No. 9 and Case No. 0 (Baseless),” referring to her own battles with public perception.9 This blurring of lines between the actor and the character emphasizes that the struggle for evidentiary credibility is a lived reality for Pakistani women, not just a plot point.

Table 1: Comparative Evidentiary Standards

| Feature | Classical 7th Century Context | Modern 21st Century Context | Case No. 9 Representation |

| Crime | Zina (Adultery/Fornication) | Zina-bil-Jabar (Rape) / Hirabah | Sexual Assault by Employer |

| Primary Evidence | 4 Male Eyewitnesses | Forensic Evidence (DNA, CCTV) | CCTV Footage (Digital Witness) |

| Circumstantial Evidence | Qarinah (Weak, supported Tazir only) | Qarinah Qat’iyyah (Strong, can support conviction) | Call logs, deleted footage |

| Objective (Maqasid) | Privacy (Satr), Prevention of Slander | Justice (Adl), Protection of Life/Honor | Public Exposure of Truth |

| Role of Victim | Silent unless corroborated | Central witness; testimony corroborated by science | Sehar as active prosecutor |

Thematic Epilogue: The Light of An-Nur in the Fiber-Optic Age

The title of the Quranic chapter governing these laws is Surah An-Nur—The Light. Light is a metaphor for truth; it dispels darkness and reveals reality. In 7th-century Arabia, the “light” of truth was carried by the voices of the community—four upright men illuminating the dark corners of accusation.

In the 21st century, “light” travels through the fiber-optic cables of CCTV networks and the laser scanners of DNA sequencers. Case No. 9 demonstrates that the “essence” of the four-witness requirement is not the number “four” or the gender “male,” but the attribute of Certainty (Yaqin).

When Sehar Moazzam stands in court, vindicated not by men but by a memory card, she embodies the modern realization of An-Nur. The drama argues that refusing to accept forensic science as the “Modern Witness” is akin to closing one’s eyes to the light. The four-witness rule remains a divine protection for the privacy of consensual acts, ensuring the state does not peek into bedrooms. But for the violence of rape, the “Silent Witness” of science must be allowed to speak, screaming the truth that human tongues are often too afraid to utter. Only by embracing this evolution can the legal system honor the Quranic mandate to “stand out firmly for justice” (Quran 4:135), ensuring that no Kamran can ever use the “shortcut” of wealth to bypass the “highway” of truth.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment