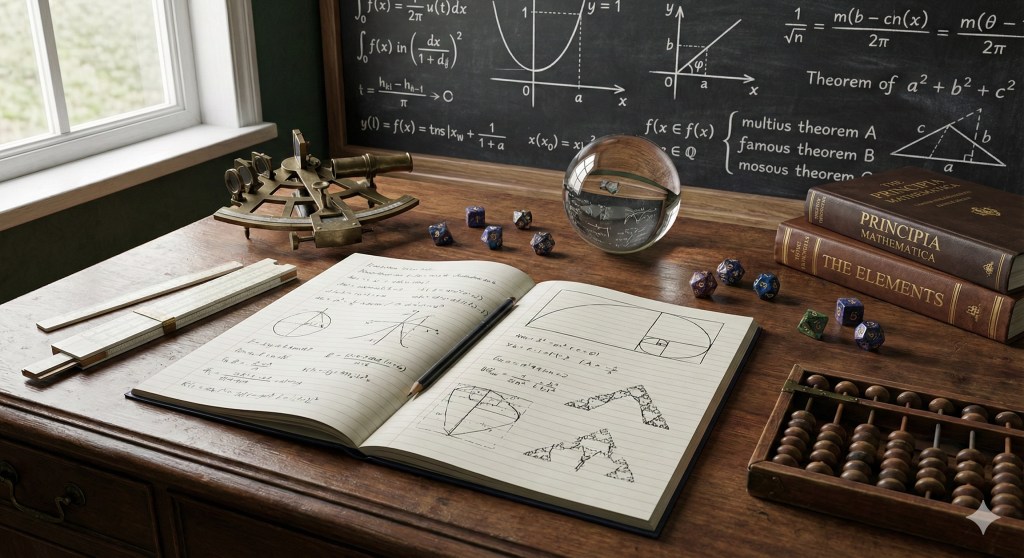

Epigraph:

He is the First and the Last, and the Manifest and the Hidden, and He knows all things full well. (Al Quran 57:3)

We have created the heavens and the earth and all that is between the two in accordance with the perfect truth (mathematics) and wisdom. (Al Quran 15:85)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

Most mathematicians eschew traditional religious belief yet embrace a kind of “mathematical heaven” – an abstract realm of numbers and forms – with near-religious conviction. Surveys show that only a small minority of elite mathematicians profess belief in God, yet a large majority consider mathematical objects to have real, independent existenceblog.larrydavidson.comblog.larrydavidson.com. This article explores this paradox: why rational minds trust unseen mathematical realities but remain skeptical of a divine creator. We examine the philosophy of mathematical Platonism, its metaphysical implications, and how some mathematicians reconcile (or fail to reconcile) their belief in eternal mathematical truths with belief in a higher consciousness. By delving into historical perspectives – from Plato’s realm of Forms to modern mathematicians’ testimonies – we weigh whether the “unseen realm” of mathematics might point toward a deeper metaphysical truth. In doing so, we consider the provocative idea that the abstract truths of mathematics, which appear necessary and timeless, could be thoughts in the mind of an ultimate consciousness (what religious traditions call God).

Introduction: Mathematicians and the Unseen Realm

In popular imagination, mathematicians are the ultimate rationalists – seekers of proof who trust only in what can be rigorously demonstrated. It may come as a surprise, then, that mathematicians often hold quasi-mystical beliefs about the nature of mathematics itself. A famous anecdote by science writer Jim Holt highlights this contrast. In a New York Times piece, Holt noted that members of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences who are mathematicians were “two and a half times” more likely to believe in God than their biologist peers – yet even so, only about 14.6% of those mathematicians affirmed a belief in a personal Godblog.larrydavidson.com. In absolute terms, most top-tier mathematicians are not religious. However, Holt revealed a striking fact: “Most mathematicians believe in heaven. Not a heaven with angels, but one populated by the abstract objects they devote themselves to studying”blog.larrydavidson.com. In other words, an overwhelming majority embrace the idea that numbers, equations, and geometrical forms inhabit an invisible, timeless domain of reality. When Holt informally polled an international conference of elite mathematicians in Berkeley, about three-quarters raised their hands identifying as “Platonists,” meaning they believe mathematical entities exist objectively, independent of human mindsblog.larrydavidson.com. Mathematicians, Holt quipped, “are no strangers to belief in the unseen”blog.larrydavidson.com – albeit an unseen world of ideas rather than of angels.

This paradox raises a profound question: How can so many brilliant mathematical minds place faith in an invisible mathematical heaven, yet remain unconvinced of a divine heaven or a God? Are these beliefs truly comparable, or are they fundamentally different in the eyes of mathematicians? To explore this, we must understand what mathematicians mean by a “mathematical heaven” and why they find it so compelling. We must also probe the metaphysical implications of believing in an unseen realm of mathematical truths. Is this belief purely about the nature of mathematics, or does it inadvertently brush against theology – perhaps even providing a backdoor to God? As we will see, some mathematicians and philosophers have argued that the existence of a mathematical realm points to an ultimate Mind behind realityaish.comchristianscholars.com. Others maintain that believing in abstract objects is a far cry from religious faith, insisting that mathematics’ unseen world is grounded in logic and necessity rather than supernatural agency.

What follows is a deep but accessible exploration of these themes. We will travel from Plato’s philosophy to modern surveys of scientists’ beliefs, from the fervent Platonism of many mathematicians to the ways some have linked mathematics with the divine. Along the way, we remain mindful of Sir Francis Bacon’s admonition: we read not merely to “contradict” but “to weigh and consider.” The goal is not to advocate a particular belief, but to illuminate how and why mathematicians can be “true believers” in one unseen realm while skeptical of another, and what that might mean for the broader dialogue between science, mathematics, and spirituality.

Mathematical Platonism: A “Heaven” of Abstract Truths

To grasp why mathematicians speak of a “mathematical heaven,” we must first understand mathematical Platonism. This is the philosophical view that mathematical entities (numbers, shapes, sets, functions, etc.) are not mere human inventions or convenient fictions, but real things that exist in an abstract realm. The term “Platonism” harkens back to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, who taught that beyond the physical world lies a higher reality of perfect Forms or Ideas – eternal templates of which the objects we see are imperfect copies. In Plato’s famous allegory, we are like prisoners in a cave, mistaking shadows for reality; the true forms (for example, the perfect circle, the essence of “tree,” or the ideal of “Justice”) exist in the bright world outside the cave. Mathematical Platonism applies this thinking to mathematics: the perfect circle, the infinite set of prime numbers, the value of π – these are not invented by us but discovered, as if they were “out there” waiting to be found.

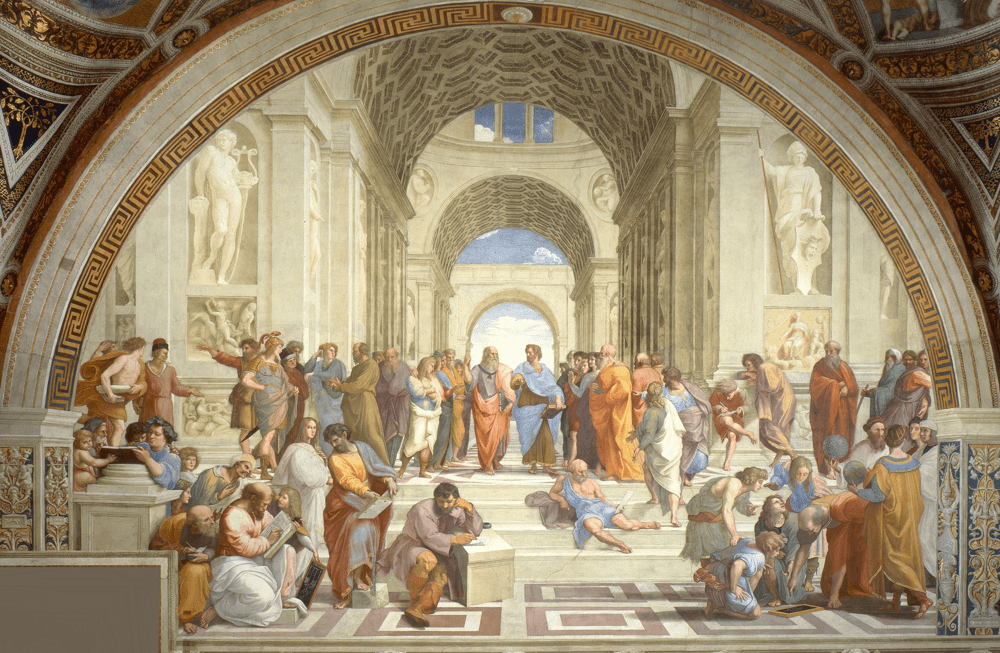

A Renaissance depiction of ancient philosophers engaged in debate about the nature of reality. In the center, one figure gestures upward toward a transcendent realm of Forms, while another extends his hand outward, emphasizing grounded experience. This artwork, The School of Athens by Raphael (1509–1511), symbolizes the enduring dialogue between idealism (the belief in unseen absolutes) and empiricism (the reliance on the observable world). The Platonic view that mathematics taps into a higher, unseen reality has been influential among mathematicians throughout history.

For a working mathematician, Platonism often manifests as the gut-feeling that mathematical truths are “out there” to be discovered rather than arbitrarily created. If one mathematician proves a theorem today and another independently proves the same theorem tomorrow, it feels as though they both accessed the same pre-existing truth. “Those of us who are Platonists believe that mathematical objects are truly out there, waiting to be discovered,” writes mathematics teacher Larry Davidson, summarizing this viewblog.larrydavidson.com. The great English mathematician G.H. Hardy unabashedly expressed this belief: “I believe that mathematical reality lies outside us, that our function is to discover or observe it, and that the theorems which we prove…are simply the notes of our observations.”todayinsci.com In Hardy’s eyes, mathematicians are more like astronomers charting distant galaxies than like inventors building gadgets; the galaxies of prime numbers and geometric forms exist whether or not we see them. Similarly, the eminent 20th-century logician Kurt Gödel – famed for his incompleteness theorems – was an ardent Platonist. Gödel argued that “mathematics describes a non-sensual reality, which exists independently both of the acts and [of] the dispositions of the human mind and is only perceived, and probably perceived very incompletely, by the human mind.”mv.helsinki.fi This striking claim asserts that there is a realm of mathematical reality not accessible to our senses (hence “non-sensual”), which would exist even if no human minds ever grasped it. Our mathematical intuition is, in Gödel’s view, a bit like a form of extrasensory perception peering into that abstract realm.

When Holt described mathematicians communing with a “realm of timeless entities through a sort of extrasensory perception,” he was half-playfully characterizing this Gödelian ideablog.larrydavidson.com. Many mathematicians will admit that in practice, doing mathematics sometimes feels like discovery via intuition – a sudden insight or an elegant solution can appear as if it were “revealed” rather than assembled step by step. (It’s no coincidence that mathematicians often use quasi-religious language, calling an elegant proof “beautiful” or speaking of “eureka” moments of revelation.) In a concrete sense, advanced mathematics proceeds by rigorous proof, not mysticism. But the widespread Platonist mindset provides a philosophical justification for why proofs work: they succeed because there is a definite truth out there to be found. Every consistent mathematical statement, the Platonist holds, has a definite truth value (true or false) whether we know it or not. This stance is sometimes called truth-value realism, and Platonism provides its most straightforward explanation – namely, that mathematical statements are true or false about something real (the abstract objects)plato.stanford.eduplato.stanford.edu.

Not all mathematicians and philosophers agree with Platonism. Some adopt nominalism or formalism, viewing math as a creation of human language or symbols with no existence beyond our minds and physical chalkboards. For these anti-Platonists, saying “the number 7 exists” is like saying “Sherlock Holmes exists” – true only in the context of a story or a formal system, not in an external reality. However, nominalism often strikes working mathematicians as clashing with their experience of math’s objectivity. Even those who have never heard the term “Platonism” might operate under what philosopher Penelope Maddy calls “working realism,” behaving as if mathematical objects are real because that methodology is so successfulplato.stanford.eduplato.stanford.edu. The fact that mathematical results are consistent worldwide – $2+2=4$ in every culture, prime numbers follow the same distribution whether studied in India or Australia – gives the impression that mathematics has an existence independent of any one person or society. As Holt pointed out, if intelligent aliens exist on a planet orbiting another star, we fully expect they would know the same prime numbers and geometric principles; they might even know truths we have yet to discover, but “42 won’t turn out to be prime on Gliese 581c”blog.larrydavidson.com. This universality is a hallmark of something real, not arbitrary.

There is also the uncanny effectiveness of mathematics in describing the physical world. The physicist Eugene Wigner famously marveled at “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences,” essentially asking why pure math dreamed up in ivory towers ends up predicting the behavior of electrons or galaxies so precisely. From Newton’s equations to Einstein’s tensors, it often feels as if nature is written in mathematical code. For a Platonist, this is no surprise: the physical world behaves mathematically because it instantiates those pre-existing mathematical forms. In the Platonic view, a perfect circle exists as an ideal form, and any ripples or planetary orbits approximating circles in the material world are echoes of that ideal. Little wonder, then, that Galileo – a deeply mathematical scientist – declared “Mathematics is the language in which God has written the Universe.”indiatoday.in Even a non-theistic Platonist might rephrase that to say mathematics is the language of reality itself.

In sum, the mathematical heaven that most mathematicians believe in is not a heaven of supernatural beings but a metaphor for this Platonic realm of truth. It is a “heaven” populated by “perfect spheres, infinite numbers, the square root of minus one and the like,” as Holt vividly wroteblog.larrydavidson.com. These entities don’t occupy physical space or time; you cannot stub your toe on the number 7 or point a telescope at π. Yet to the committed Platonist, they are as real as – indeed more enduring than – the material world. A triangle drawn in chalk on a blackboard is imperfect and will be wiped away, but the theorem of Pythagoras about the square of the hypotenuse is eternally true and invulnerable. Hardy put it poetically: “Archimedes will be remembered when Aeschylus is forgotten, because languages die and mathematical ideas do not. ‘Immortality’ may be a silly word, but probably a mathematician has the best chance of whatever it may mean.”todayinsci.com. In a very real sense, mathematical Platonists see mathematics as conferring a kind of immortality – a glimpse into a deathless realm of truth. It is little wonder that this belief can inspire near-religious awe, even as many of its adherents reject conventional religion.

Mathematicians vs. God: A Rational Crisis of Faith?

If belief in an unseen, eternal realm of mathematical forms is so common among mathematicians, why is belief in God so comparatively scarce? The survey Holt cited (originally conducted in the late 1990s by researchers Edward Larson and Larry Witham) revealed that over 85% of NAS mathematicians did not accept the “God hypothesis”blog.larrydavidson.com. For biologists and physical scientists, the rate of disbelief was even higher (a stunning ~94.5% of biologists in the NAS disbelieved in God)blog.larrydavidson.com. This suggests that as a group, elite scientists – including mathematicians – are far more secular than the general population. Yet within that community, mathematicians showed a relatively greater openness to theism. Why might that be? One possibility is that mathematics, with its intimations of eternity and absolutes, attracts or engenders a mindset more hospitable to the concept of an ultimate reality (which could be analogized to God). In contrast, biologists, who study the contingency and messiness of evolving life, might see less evidence of any eternal or transcendent order in their work. Still, even among mathematicians, open belief in God remains a minority position.

It’s worth noting that most humans tend to stick with the religion they were born into – a point the question raises. This implies that religious belief (or disbelief) is often influenced more by culture and upbringing than by an objective evaluation of evidence. Mathematicians are humans too; their religious views likely reflect personal and cultural factors more than their mathematical training. The legendary mathematician Paul Erdős, for example, called himself a “Jewish atheist” and spoke of the Book – an imaginary divine book in which God had written down all the most elegant mathematical proofs – but he did not believe in a personal God. Erdős’s playful references to “God’s book” of proofs were a way to express the beauty and perfection of mathematical truthsblog.larrydavidson.com, not an actual statement of faith. Many mathematicians similarly compartmentalize: they may use metaphorical or spiritual language about math, yet remain strictly naturalistic about everything else.

From a rational standpoint, a mathematician might argue that belief in the mathematical realm is justified by the success and consensus of mathematics, whereas belief in God does not enjoy such empirical success or agreement. No matter one’s culture or faith, if correctly reasoned, one finds the same ratio for a circle’s circumference to its diameter (π), or the same solutions to a quadratic equation. These truths compel agreement in a way that religious claims do not. In this sense, the objectivity of mathematics can be seen as evidence for an external reality of mathematical forms. By contrast, there is no comparable objective evidence for God that compels near-universal agreement. The methodologies also differ: mathematical beliefs are subject to proof or refutation, whereas religious beliefs typically are not. Thus, a mathematician might say, I “believe” in the number 2 because its properties can be rigorously demonstrated and used predictively, but belief in God offers no such proof. In short, they might see their Platonist conviction not as faith but as a reasoned conclusion from the nature of mathematics. God, in their view, belongs to a different epistemological category.

However, the line is not always so clear-cut. Some mathematicians and physicists do feel their work points toward the divine. Throughout history, a number of great mathematical minds have been religious – sometimes in unorthodox ways. Blaise Pascal, who made important contributions to probability and geometry, had a profound Christian conversion and even formulated a famous argument for faith (Pascal’s Wager). Leonhard Euler, one of the most prolific mathematicians ever, was outwardly devout (though he’s also attributed a tongue-in-cheek theological retort: during a debate with a skeptic, Euler supposedly declared, “Sir, $(a + b^n)/n = x$, hence God exists – reply!”). While the anecdote is apocryphalblog.larrydavidson.com, it captures the stereotype that mathematicians might equate mathematical truth with divine truth.

Perhaps the most intriguing case is Srinivasa Ramanujan, the Indian mathematical genius. Ramanujan was deeply spiritual and credited his astounding mathematical insights to supernatural sources. “By his own admission, he received 3,900 formulae from [the] Hindu goddess Namagiri,” reports an article on his lifeindiatoday.in. Ramanujan said that in dreams, the goddess would present mathematical results to him, which he would verify upon waking. He often asserted, “An equation has no meaning for me unless it expresses a thought of God.”indiatoday.in This remarkable statement bridges the two realms completely: for Ramanujan, discovering a math formula was literally hearing the voice of the divine. To his collaborator G.H. Hardy (an avowed atheist and Platonist), Ramanujan’s religious interpretations were mystifying – yet even Hardy acknowledged Ramanujan’s genius seemed otherworldly. Ramanujan’s case is extreme but not unique. Historically, the Pythagoreans of ancient Greece treated numbers almost like deities and believed in the transmigration of souls based on numerical harmonies. Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion, was driven by a belief that God had designed the cosmos with geometric harmony (Kepler spent years trying to fit planetary orbits to nested Platonic solids). Even Isaac Newton, though more physicist than pure mathematician, wrote as much on biblical prophecy and theology as he did on calculus – convinced that the same rational God who ordained mathematical laws for gravity also gave moral laws in scripture.

Despite these examples, it remains true that most modern mathematicians do not believe in a personal God, even if they are Platonists about math. The intriguing question is whether their belief in a mathematical reality has metaphysical implications that they are hesitant to trace out fully. This brings us to the crux of the issue: If one accepts a timeless, independent realm of truth, can one consistently deny any sort of higher power or organizing principle behind it? Or to put it provocatively: is mathematical Platonism actually a quasi-religious belief, and if so, shouldn’t its adherents be more open to the idea of God?

The Metaphysical Implications of Mathematical Platonism

Believing in an abstract mathematical realm is a metaphysical commitment – it says something about what reality contains. It says reality is more than just physical; there are entities that are non-physical, non-empirical, yet objectively existent. In philosophy, this edges into the territory of metaphysics and ontology (the study of what exists). A committed materialist – someone who thinks only matter and energy exist – would find Platonism hard to swallow. Yet many scientifically minded people (mathematicians included) make an exception for mathematics, granting a special status to mathematical truth. This suggests that, knowingly or not, they accept some form of dualism: a world of matter and a world of abstract forms. It’s a short step to wonder if there’s a connection or interaction between those worlds.

One common concern is the epistemology of Platonism: if mathematical objects are non-physical, how do we know about them? How can our minds, rooted in a physical brain, access a timeless Platonic heaven? This is known as the Benacerraf problem in philosophy of mathematics, and it mirrors questions in religion: How can a human mind know the mind of God or the divine realm? Platonists offer various answers. Some, like Gödel, posit a kind of rational intuition – an almost mystical insight by which we “see” mathematical truths. This is strikingly similar to how religious mystics describe knowing God or the divine: not through the senses, but through an inner illumination. In Holt’s anecdote, he tongue-in-cheek called it “a sort of extrasensory perception”blog.larrydavidson.com. The parallel isn’t lost on people. Philosopher Mary Leng notes that a staunch Platonist must accept either a mysterious connection between mind and abstracta or conclude that our ability to do math is itself a brute fact miracle. Critics of Platonism, like philosopher Hartry Field, have even argued that if one is unwilling to countenance the supernatural, one should be equally wary of abstract objects – since both introduce entities that cannot be detected by empirical meansplato.stanford.eduplato.stanford.edu. In short, Platonism lives in a metaphysical twilight zone that is uncomfortably adjacent to theology.

Importantly, mathematical Platonism implies eternity and necessity. If numbers and forms exist “out there,” they presumably do so eternally (outside time) and necessarily (they could not not exist). The number 5, for instance, doesn’t rust, decay, or cease to be true at some point – it’s timeless. And one might argue that even God couldn’t make 2+2 equal anything but 4; the truth of that equation is seen as logically necessary. This has led to debates: is God constrained by mathematics, or is mathematics part of God’s nature? For example, medieval theologians like St. Augustine directly integrated Plato’s Forms with Christian doctrine, teaching that mathematical truths (and all Forms) exist as ideas in the mind of Godchristianscholars.com. In this view, when a mathematician discovers a theorem, she is literally thinking God’s thoughts after Him. Augustine’s move was elegant: it gave mathematics a secure existence (in God’s mind) and solved the epistemology issue (our minds, made in God’s image, can access His ideas to an extent). This concept endured through centuries of Christian thought. The mathematician and philosopher Leibniz echoed it, as did Cantor in the 19th century.

Georg Cantor, who founded set theory and revolutionized our understanding of infinity, was a devout man who explicitly placed infinities in a theological context. Cantor distinguished three realms of existence: “(1) the mind of God, (2) the human mind, and (3) the physical universe.” He held that **“the set of everything” and the ultimate infinite (Absolute Infinity) is “comprehended only in the Mind of God.”aish.com Furthermore, “Cantor believed that God put the concept of number, both finite and transfinite, into the human mind and that their existence in the Mind of God was the basis for their existence in the human mind.”aish.com In Cantor’s metaphysics, every mathematical truth we grasp is grounded in God’s own eternal knowledge. This is a clear example of how a Platonist view of math can segue into theistic belief. Cantor even referred to the “Absolute Infinity” (which in set theory is a kind of unattainable infinity beyond all infinities) as essentially God’s domain – the only actual infinite is God, he said, with all lesser infinities being His creationaish.com.

Not every mathematician who is a Platonist goes in this theological direction. Many compartmentalize the two realms: math is objective truth, God (if He exists) is another matter entirely. Yet the structural similarities between belief in a mathematical heaven and belief in a spiritual heaven are hard to ignore. Both involve conviction in unseen realities that give meaning and order to what we observe. Both involve a sense of transcendence – going beyond the material. And both can profoundly influence one’s worldview and behavior (even if, as Holt wryly noted, mathematicians don’t become evangelists of Platonism in the public square or launch crusades over the reality of πblog.larrydavidson.com).

Where the two beliefs differ is perhaps in personal implication and moral dimension. The mathematical realm, even if real, is impersonal. It doesn’t answer prayers, nor does it demand ethical behavior. One does not ask the number 7 for forgiveness or expect comfort from the Pythagorean theorem in times of distress. God, as conceived by religion, is usually a personal being – one with will, intentions, and moral attributes. Mathematicians may find it easier to believe in an abstract realm that makes no personal demands on them, versus a personal God who might. In a lighter vein, one might say mathematical Platonism comes with all of the ontological daring of belief in the unseen, but none of the uncomfortable responsibilities of religious faith. As Holt joked, no Platonist mathematician feels compelled to “fly planes into buildings” over the truth of the axiomsblog.larrydavidson.com. In other words, the mathematical heaven doesn’t spawn fanatics or ethical dictates – it’s safely confined to the intellectual sphere.

However, some thinkers argue that once you accept a permanent, necessary, non-physical reality (like the mathematical realm), you have opened the door to a Necessary Being of some kind. Perhaps the abstract realm is not as impersonal as it looks. The British physicist and theologian John Polkinghorne suggested that the uncanny ability of our minds to comprehend deep mathematical structures that later turn out to describe the universe hints at a congruence between our minds, the physical world, and the Platonic world – a congruence most simply explained by all three arising from a single source (which he identifies as the Mind of God). Likewise, philosopher Alvin Plantinga has argued that abstract objects fit more comfortably in a theistic worldview (as ideas in God’s mind) than in a naturalistic one. While atheistic Platonists see no need for that additional step, the conceptual move of placing math in God’s mind has a long pedigree, as we saw with Augustine and Cantor. It solves one problem but raises another: if all math resides in God’s intellect, then God must exist as surely as 1+1=2 exists, and few secular mathematicians are ready to accept that equivalence.

The author of the question poses a “one-liner” argument to challenge mathematicians who reject God while embracing mathematical heaven: namely, mathematical formulas and equations are like thoughts, and thoughts require a mind. If there were no conscious minds, mathematics would not exist or even be conceivable. Therefore, mathematics itself is contingent on consciousness; it cannot be the ultimate necessary reality. And since something must exist necessarily (for nothing comes from nothing – ex nihilo nihil fit), the most plausible candidate is not mathematics per se but an ultimate consciousness (i.e. God) that grounds both mathematics and physical reality. In simpler terms, the argument says: if you believe math is real and eternal, ask yourself whose thoughts those truths are. Human minds are latecomers in the universe; if mathematical truths existed before humans, perhaps they existed in a cosmic Mind. This line of reasoning effectively flips the script on Platonist mathematicians: you grant one unseen realm (math) is necessary because the universe runs on it, but you ignore that math itself might need a necessary foundation.

Is this argument compelling? It certainly resonates with the aforementioned views of Augustine and Cantor. It aligns with Ramanujan’s feeling that an equation is a divine thoughtindiatoday.in. However, a skeptic might counter that this assumes what it tries to prove. Maybe mathematical truths don’t need a thinker at all; maybe they just are. This is the pure Platonist position: mathematical forms are sui generis, existing in a third realm (not physical, not mental). To a strict Platonist, asking “but in whose mind do they exist?” is a category mistake – they don’t exist in a mind; minds discover them precisely because they exist independently. The theistic rejoinder is that existence in absolute independence is essentially what believers mean by God (a self-existent reality), so either way you haven’t escaped a kind of god-like concept. Indeed, some theologians call the Platonic realm “the Mind of God” without any further qualifierschristianscholars.com. In that framing, many mathematicians unknowingly do believe in “God,” just not in a God that answers prayers or has sent prophets – they believe in God as an impersonal ground of logical truth.

This debate touches on deep philosophical waters: What does it mean for something to exist necessarily? Could abstract principles exist without a concrete knower? And if not, does that force us to accept a cosmic Knower? Different thinkers land in different places. Yet, regardless of one’s stance, exploring these questions underscores that mathematical Platonism is not a trivial belief. It has profound implications, tying into arguments about the origin and nature of reality itself.

Epilogue: Weighing the Unseen

Mathematicians, perhaps more than any other scientists, live comfortably with the unseen. To practice mathematics is to operate on faith in the intelligibility and reality of invisible things – whether that “faith” is emotional or purely logical. Most humans, as noted, do not rationally choose their religious beliefs; they inherit them. Mathematicians like any people are influenced by upbringing, yet in their professional life they rigorously test and question everything. It is fascinating, then, that so many mathematicians emerge from that gauntlet of skepticism as believers in an unseen Platonic world. They did not pick that belief up from childhood tales – it likely grew from their own encounters with the power and mystery of mathematics. In that sense, the mathematician’s “heaven” is an earned conviction, one arrived at through reason and experience rather than tradition and habit.

What can we conclude from the paradox that opened our discussion? Are mathematicians hypocritical to embrace a mathematical heaven but not a deity, or are these stances justifiably distinct? The answer may lie in how one views the nature of mathematics vis-à-vis personal faith. Many mathematicians would say their belief in mathematical reality is not mystical but logical – it is the simplest explanation for why math works so well. They might view religious belief as unsupported by such evidence. However, others (including a subset of mathematicians themselves) would point out that any belief in something eternal and non-material – be it numbers or gods – requires a step beyond empiricism. It requires openness to a metaphysical dimension. In that light, the gap between mathematical Platonism and theism might not be as wide as it seems. Both express a yearning for or confidence in an ordered reality beyond the flux of the physical world. Both could be seen as responses to the intuition that “nothing comes from nothing,” that the universe’s coherence points to a foundational principle or mind.

As observers, we need not insist that every mathematician become a theist or that every theist adopt Platonism. But we can appreciate the subtle ways in which these domains overlap. When a mathematician raises her hand in Berkeley to profess Platonismblog.larrydavidson.com, she is, in a way, making a metaphysical leap of faith – a carefully reasoned faith in a hidden order. And when a person of faith speaks of a divine Logos (logic) upholding creation, he is not so far from the mathematician who speaks of eternal truths. Both are, as Bacon urged, trying not to contradict reality, but to “weigh and consider” what must be true for us to find ourselves in an intelligible world.

In the end, the interplay between mathematical heaven and God invites each of us to reflect on our own beliefs about the unseen. Mathematics shows that sometimes the unseen can leave indelible footprints (in the form of theorems and natural laws) that convince even hardened skeptics of its reality. Might other unseen realities leave footprints as well? The best mathematicians, like good scientists, examine evidence with ruthless logic – but as humans, they also feel wonder and even reverence when the logic unveils something sublime. That reverence is perhaps the common ground between the mathematical Platonist and the believer in God. Both stand in awe of a reality greater than themselves. One finds it in theorems, another in theology – some, like Ramanujan, in bothindiatoday.in. Neither has full proof of why such a reality exists at all. For now, we can marvel that it does, and continue the search – weighing, considering, and, occasionally, glimpsing a realm where truth abides, whether we call it heaven or something else.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment