Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

How are the 25-30 million Sikhs led to Monotheism?

The Sikh Guru who compiled the Adi Granth, the first official edition of the Sikh holy scripture, was the fifth Guru, Guru Arjan Dev (Arjan), completing the work in 1604 before its installation at the Golden Temple. This sacred text, containing hymns from Sikh Gurus and saints, formed the basis for the final Guru Granth Sahib, which Guru Gobind Singh later declared the eternal living Guru. It was the first compilation of sacred hymns, including those from Guru Nanak and other Gurus and saints, collected to preserve the genuine teachings. This foundational text was later expanded by Guru Gobind Singh (1666-1708), adding hymns from Guru Tegh Bahadur and declared the perpetual Guru, becoming the Guru Granth Sahib.

The Sri Guru Granth Sahib stands as a singular monumental text in the annals of world religious history, holding a status that transcends the conventional definitions of scripture. It is revered not merely as a holy book but as the Shabad Guru—the Living, Eternal Guide of the Sikh faith. Canonized in 1708 by the tenth Sikh Master, Guru Gobind Singh, this massive volume of 1,430 angs (limbs) represents the culmination of a centuries-long spiritual movement that sought to democratize the divine. This report provides a comprehensive, expert-level examination of the Granth’s historiography, tracing its complex compilation process from the early Pothi Sahibs to the Adi Granth (1604) and finally the Damdami Bir. It offers a granular analysis of its intricate structural organization based on the Raag (musical mode) system, detailing the hierarchy of musical measures that dictate its recitation. A distinct and substantial portion of this dossier is dedicated to the investigation of the Islamic and Sufi contributions to the canon, analyzing the theological convergence found in the works of Sheikh Farid, Bhagat Bhikhan, and the Muslim minstrels, while addressing historical controversies regarding authorship and identity. The report concludes with a thematic exploration of the scripture’s universalist philosophy, positing the Guru Granth Sahib as a repository of interfaith harmony and monotheistic egalitarianism.

Chapter 1: The Ontological Status and Significance of the Shabad Guru

1.1 The Concept of the Living Guru

In the Sikh tradition, the Sri Guru Granth Sahib (SGGS) occupies an ontological position that is unique among the world’s major religious texts. It is not viewed as a passive historical anthology or a mere record of revelation; it is accorded the status of the “Eternal Guru”.1 This doctrine marks a decisive shift from the lineage of human Gurus to the sovereignty of the Word (Shabad). The foundational Sikh belief asserts that the Guru is not the physical body, but the Jot (Divine Light) and the Gyan (Knowledge) contained within. This Light passed sequentially through ten human forms, from Guru Nanak Dev to Guru Gobind Singh, and was finally invested in the Granth Sahib in 1708.3

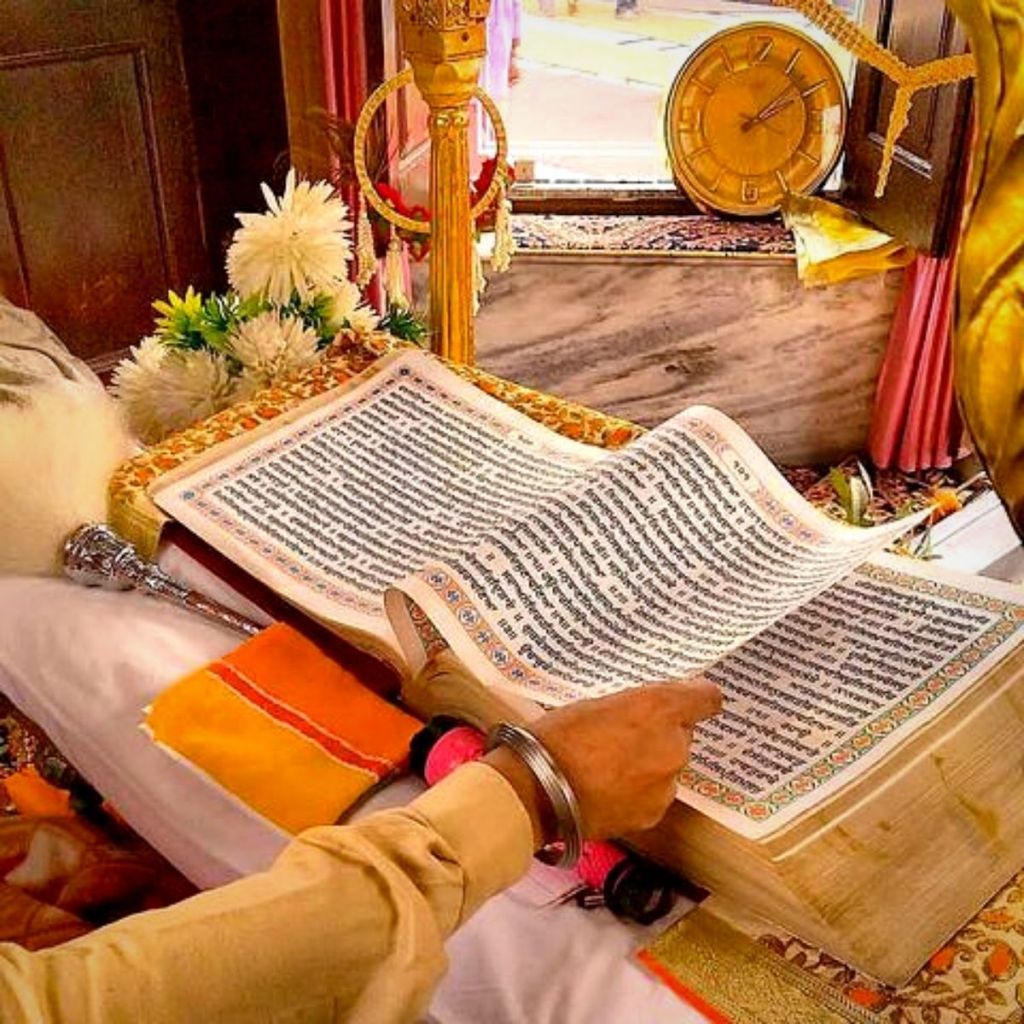

Consequently, the physical volume is treated with the reverence due to a living sovereign. In Gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship), the scripture is installed on a throne (Takht) under a royal canopy (Chanani). It is covered with rich robes (Rumala) and fanned with a fly-whisk (Chaur Sahib), symbols of royalty in South Asian culture reserved for kings and deities.4 The vocabulary used to describe the text reinforces this anthropomorphic yet transcendent status: the pages are not referred to as pages, but as Angs (limbs), suggesting that the scripture is the “Body of the Guru”.5 When a Sikh bows before the Granth, they are bowing to the wisdom and the divine frequency contained within the Shabad, which is considered the essential form of the Guru.

1.2 The Linguistic Landscape: Sant Bhasha

The linguistic composition of the Guru Granth Sahib is a testament to its universalist intent and its rejection of linguistic elitism. Unlike the Vedas, which were preserved in Sanskrit (accessible only to the priestly caste), or the Quran in classical Arabic, the Guru Granth Sahib was composed in the languages of the masses.4

The primary script used is Gurmukhi, a script standardized by the second Guru, Guru Angad Dev, specifically for the preservation of the hymns.4 However, the script serves as a vehicle for a diverse array of languages. The text utilizes a medieval literary blend known as Sant Bhasha (Saint Language), a lingua franca of North Indian mystics that incorporates vocabulary and grammatical structures from:

- Punjabi (including dialects like Lahnda/Multani and Majhi)

- Sanskrit and Prakrit

- Persian and Arabic

- Braj Bhasha and Khari Boli

- Marathi, Sindhi, and Bengali.4

This polyglot nature ensured that the divine message was accessible to a broad spectrum of society across the Indian subcontinent. By elevating common dialects to the status of revelation, the Gurus challenged the hegemony of sacred languages and asserted that truth could be expressed in any tongue.

Chapter 2: Historiography and Canonization

The compilation of the Guru Granth Sahib was a deliberate, rigorous, and multi-stage historical process designed to preserve the authenticity of the Gurus’ revelations and protect the canon from interpolation. This process spanned over a century, from the early collections of Guru Nanak to the final canonization by Guru Gobind Singh.

2.1 The Pre-Compilation Era and the Pothis

The process of collecting Gurbani (the Guru’s words) began with the founder, Guru Nanak Dev. Historical records indicate that Guru Nanak carried a pothi (book of hymns) during his vast travels (Udasis), recording his own revelations and the hymns of the saints he encountered.3 This tradition of manuscript preservation was critical in a culture dominated by oral transmission.

Guru Nanak passed this collection to his successor, Guru Angad Dev, who in turn added his own compositions and passed the collection to Guru Amar Das.3 By the time of the third Guru, the collection had grown significantly. Guru Amar Das commissioned the compilation of these hymns into two volumes, known as the Goindwal Pothis. These manuscripts were scribed by his grandson, Sahansar Ram, and were kept by his son, Baba Mohan.8

2.2 The Challenge of Authenticity and the Minas

By the time of the fifth Guru, Guru Arjan Dev, a significant theological and institutional challenge had emerged. Rival claimants to the Guruship—specifically the sect known as the Minas, led by Guru Arjan’s estranged older brother, Prithi Chand—began circulating spurious hymns.9 These compositions, often referred to as “Kachi Bani” (false/immature hymns), imitated the style of Nanak and were being passed off as authentic.

To inoculate the Sikh community against these interpolations and to establish a definitive canonical text, Guru Arjan Dev decided to compile an authentic anthology that would serve as the unalterable spiritual constitution of the faith.3

2.3 The Compilation of the Adi Granth (1604)

In 1604, Guru Arjan Dev undertook the monumental task of compiling the Adi Granth (First Book). He established a camp at Ramsar Sarovar in Amritsar, a secluded location conducive to literary work.10

- Sourcing the Manuscripts: Guru Arjan famously traveled to Goindwal to personally request the Goindwal Pothis from Baba Mohan. Despite initial reluctance, Baba Mohan was won over by the Guru’s humility and poetry, surrendering the manuscripts which served as the primary source material.3

- The Scribe and the Dictation: The Guru employed his trusted uncle and scholar, Bhai Gurdas, as the primary scribe. Guru Arjan would dictate the hymns, often editing and arranging them according to the musical Raag system.10

- Selection Criteria: The Guru applied a rigorous theological litmus test. Only those hymns that resonated with the core principles of Gurmat (Guru’s Wisdom)—strict monotheism, equality of all humans, rejection of ritualism, and devotion to the One Formless Lord—were included. Hymns that promoted caste, idolatry, or asceticism were rejected.9

- Installation: The completed volume, known as the Kartarpuri Bir, was installed inside the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) on September 1, 1604. The venerable Baba Buddha Ji was appointed as the first Granthi (custodian/reader).4

2.4 The Damdami Bir and the Final Guruship (1708)

The Adi Granth remained with the Dhir Mal clan (descendants of the sixth Guru’s grandson) who refused to return it to the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, guarding it as a symbol of their own claim to authority.3

In 1705-1706, during a respite at Talwandi Sabo (now known as Damdama Sahib) following the evacuation of Anandpur, Guru Gobind Singh prepared the second and final recension of the scripture.3

- Memory and Dictation: According to Sikh tradition, Guru Gobind Singh dictated the entire volume from memory to the scribe Bhai Mani Singh, as the original Kartarpuri Bir was unavailable.3

- The Inclusion of the Ninth Mahala: Crucially, Guru Gobind Singh added the hymns of his father, Guru Tegh Bahadur (115 hymns and sloks), to the canon.3 This addition finalized the theological content of the Granth. It is notable that Guru Gobind Singh did not include his own extensive martial and mythological poetry (which is collected separately in the Dasam Granth), thereby preserving the Adi Granth’s focus on devotional, quietist spirituality and Naam Simran (meditation on the Name).

- The Declaration of Sovereignty: In October 1708, at Nanded (Maharashtra), shortly before his passing, Guru Gobind Singh ended the lineage of living human Gurus. He placed a coconut and five paise before the Granth and bowed, declaring:”Aagya bhai Akal ki Tabhi chalayo Panth, Sabh Sikhan ko hukam hai Guru Manyo Granth”(By the command of the Timeless, the Panth was established; all Sikhs are commanded to accept the Granth as the Guru).1

Chapter 3: Structural Architecture and The Musical System

The organization of the Guru Granth Sahib is complex, eschewing chronological or thematic arrangement in favor of a musical and aesthetic structure. This design emphasizes that the text is meant to be sung (Kirtan) and experienced emotionally, not just read intellectually.13 The structure is designed to guide the consciousness through specific emotional states toward the Divine.

3.1 The Raag System

The primary division of the scripture is based on Raags (melodic modes) of Indian Classical Music. There are 31 main Raags used in the Granth.5 Each Raag is chosen to evoke a specific spiritual mood or emotion (Rasa), aligning the listener’s consciousness with the divine message.

The Raags are not merely musical scales but are treated as aesthetic frameworks for the soul’s journey. For instance, Raag Maru is used for martial vigor and fearlessness, while Raag Vadhans expresses the pain of separation (Vairaag).

Table 1: The Sequence and Emotional Significance of the 31 Main Raags 4

| Sequence | Raag | Emotional/Spiritual Atmosphere |

| 1 | Sri Raag | Satisfaction, Balance, Grandeur, Authority |

| 2 | Majh | Yearning, Separation, Beautification |

| 3 | Gauri | Seriousness, Deep Contemplation |

| 4 | Asa | Hope, Making Effort, Optimism, Dawn |

| 5 | Gujari | Softness of heart, Prayer, Sadness |

| 6 | Devgandhari | Softness, Merging with the Divine |

| 7 | Bihagra | Aesthetic beauty, Night-time longing |

| 8 | Vadhans | Vairaag (Detachment), Loss, Separation |

| 9 | Sorath | Motivation, Uplifting |

| 10 | Dhanasri | Inspiration, Worship (Aarti), Motivation |

| 11 | Jaitsri | Satisfaction, Sadness |

| 12 | Todi | Flexibility, Devotion |

| 13 | Bairari | Softness, Bhakti |

| 14 | Tilang | Islamic style, Yearning, Beautification |

| 15 | Suhi | Joy, Separation, Divine Love |

| 16 | Bilaval | Happiness, Bliss, Celebration |

| 17 | Gond | Wonder, Mystery |

| 18 | Ramkali | Yogic discipline, Stability, Calmness |

| 19 | Nat Narayan | Heroism, Strength |

| 20 | Mali Gaura | Seriousness, Determination |

| 21 | Maru | Martial spirit, Fearlessness, Battle |

| 22 | Tukhari | Beautification, Nature |

| 23 | Kedara | Asceticism, Focus |

| 24 | Bhairav | Stability, Destruction of Ego |

| 25 | Basant | Spring, Renewal, Joy |

| 26 | Sarang | Sadness (Thirst for God like the Rainbird) |

| 27 | Malar | Rainy Season, Separation/Union |

| 28 | Kanara | Devotion, Suffering in Love |

| 29 | Kalyan | Bhakti, Evening prayer |

| 30 | Prabhati | Morning awakening, devotion |

| 31 | Jaijavanti | Detachment (Added by Guru Tegh Bahadur) |

In addition to these, there are Mishrat (Mixed) Raags (e.g., Gauri-Deepaki, Asa-Kafi) and regional variants like Dakhani (Southern style), bringing the total variations to 60.4 The complex system of Ghar (House) further delineates the rhythm and style of singing, with numbers indicating specific beat cycles (Taals).13

3.2 Internal Hierarchy of a Raag Chapter

Within each Raag chapter, the hymns follow a strict, standardized hierarchical protocol that is consistent throughout the volume 5:

- The Shabads (Hymns) of the Gurus: These are arranged chronologically by the Guru.

- Mahala 1 (Guru Nanak)

- Mahala 2 (Guru Angad)

- Mahala 3 (Guru Amar Das)

- Mahala 4 (Guru Ram Das)

- Mahala 5 (Guru Arjan)

- Mahala 9 (Guru Tegh Bahadur)

- The term Mahala (House) identifies the author; “Mahala 1” is Guru Nanak, “Mahala 5” is Guru Arjan. This nomenclature emphasizes that the “House” (Body) changed, but the Light was the same.13

- Organization by Metrical Form: Within the author sections, hymns are grouped by length and meter:

- Chaupadas (4-stanza hymns)

- Ashtpadis (8-stanza hymns)

- Chhants (Lyrics/Songs of praise)

- Vars (Ballads/Epics).13

- Bhagat Bani: The compositions of the Saints (Kabir, Namdev, Ravidas, Farid, etc.) are placed after the Gurus’ works in each Raag.5 This placement is significant; while they are accorded the status of Gurbani, the Gurus’ writings act as the foundational structure.

3.3 The Three-Part Macro Structure

The physical volume is divided into three major sections 5:

- Nitnem (Daily Prayers) [Ang 1-13]: This pre-Raag section serves as the prologue. It contains the Japji Sahib (Guru Nanak’s philosophical masterpiece), Sodar Rehras (Evening prayer), and Kirtan Sohila (Night prayer). These are recited daily by Sikhs and are not set to Raags (except parts of Rehras/Sohila which repeat Raag compositions found later in the text).5

- The Main Body (Raag Section) [Ang 14-1353]: The bulk of the scripture, organized by the 31 Raags as detailed above. This section constitutes the vast majority of the text.

- Concluding Section [Ang 1353-1430]: This epilogue contains compositions not set to Raags, often consisting of collection of couplets or specialized forms:

- Salok Sahaskriti (Verses in Sanskrit-influenced style)

- Gatha

- Phunhe

- Chaubole

- Salok Varaan Te Vadhik (Sloks left over from the Vars)

- Salok Mahala 9 (The 57 couplets of Guru Tegh Bahadur, often recited at the Bhog ceremony)

- Mundavani (The Seal of Guru Arjan, certifying the completion and authenticity of the text)

- Ragamala (A catalog of Raags, the authorship and status of which has been a subject of historical debate, though it is included in the standard print).6

Chapter 4: Composition and Authorship

The Guru Granth Sahib contains 5,894 hymns (counts vary slightly based on classification of sloks/stanzas) contributed by 36 distinct authors.4 The diversity of this authorship is a radical theological statement, asserting that the status of “Guru” or “Knower of Truth” is not the monopoly of the Sikh Founders but is shared by any soul that has merged with the Infinite.

4.1 The Sikh Gurus

The primary contributors are the Sikh Gurus, who wrote under the pseudonym “Nanak,” emphasizing the continuity of the same divine light across generations.

Table 2: Contributions of the Sikh Gurus 4

| Guru | Number of Hymns | Percentage (Approx) | Theological Focus |

| Guru Arjan Dev (5th) | 2,218 | 32.6% | The compiler; themes of supreme devotion, sacrifice, and the peace of union (Sukhmani). |

| Guru Nanak Dev (1st) | 974 | 16.5% | Foundational metaphysics, critique of ritualism, nature of Reality (Sat). |

| Guru Amar Das (3rd) | 907 | 15.4% | Social reform, equality of women, service (Seva), fragility of life. |

| Guru Ram Das (4th) | 679 | 11.5% | Devotion, humility, the bliss of the Name. |

| Guru Tegh Bahadur (9th) | 116 | 5.9% | Vairaag (Detachment), transience of the world, fearlessness. |

| Guru Angad Dev (2nd) | 62 | 1.1% | Obedience to the Guru, discipline, physical and spiritual health. |

4.2 The Bhagats (Saints)

Guru Arjan Dev incorporated the writings of 15 Bhagats—mystics from the Bhakti and Sufi movements who lived between the 12th and 17th centuries. This inclusion is the most distinctive feature of Sikh scripture, granting the writings of a cobbler (Ravidas), a weaver (Kabir), and a Muslim ascetic (Farid) the same status as the Gurus themselves.

Major Bhagat Contributors:

- Bhagat Kabir: 541 hymns (largest non-Guru contributor). A weaver who preached strict monotheism and challenged both Hindu ritualism and Islamic orthodoxy. His work is caustic, direct, and profoundly mystical.16

- Bhagat Namdev: 60 hymns. A calico printer from Maharashtra who transitioned from worshipping the idol Vithoba to the Formless One. His hymns reflect a personal, intimate relationship with God.11

- Bhagat Ravidas: 41 hymns. A leather worker (untouchable caste) whose poetry asserts spiritual dignity and social equality. His hymn regarding Begampura (the city without sorrow) is a manifesto of a casteless, stateless utopia.11

- Others: Bhagat Trilochan, Dhanna, Beni, Jaidev, Pipa, Sain, Sadhana, Bhikhan, Parmanand, Surdas, Ramanand.11

4.3 The Bhatts and Gursikhs

- The Bhatts: 11 distinctive bards (Saraswat Brahmin poets) who traveled to the Guru’s court. Their compositions, known as Swayyas, eulogize the first five Gurus as incarnations of the Divine Light. Prominent names include Kalshar (54 hymns), Mathura, and Kirat. Their contribution bridges the gap between the Vedic tradition and the Sikh movement, as they testify to seeing the Vedic light in Nanak.4

- Gursikhs: Compositions by devotees such as Baba Sundar (author of Ramkali Sadd, describing the death of Guru Amar Das), and the minstrels Satta and Balvand.18

Chapter 5: The Islamic and Sufi Contributions to the Sikh Canon

The user has explicitly requested a detailed examination of the “Muslim origin” of parts of the Guru Granth Sahib. The scripture contains a significant volume of Islamic and Sufi theology, integrated seamlessly into the Sikh worldview. This is not merely a token inclusion but a theological validation of Islamic spirituality when directed toward the One Formless God (Allah/Ram). This section explores the specific contributors of Islamic background and the controversies and consensus surrounding them.

5.1 Sheikh Farid: The Sufi Mystic of Punjab

The most prominent Muslim contributor is Sheikh Farid (Fariduddin Ganjshakar, 1173–1266), a seminal figure of the Chishti Sufi order. His inclusion bridges the gap between Islamic mysticism and Gurmat.

- Quantitative Contribution: The Guru Granth Sahib contains 134 hymns by Sheikh Farid. This comprises 112 Sloks (couplets) and 4 Shabads (hymns) in Raags Asa and Suhi.20

- Theological Themes: Farid’s poetry is characterized by Vairaag (dispassion) and an intense fear of death and judgment (Qiyama). He emphasizes the transience of life (“The body burns like an oven”) and the need for humility (“Farid, answer evil with good; do not anger your heart”).

- The Guru-Farid Dialogue: An analysis of the text reveals a unique inter-textual dialogue. Among Farid’s 130 recorded sloks (including the 112 attributed to him), there are 18 sloks authored by the Sikh Gurus (Guru Nanak, Guru Amar Das, and Guru Arjan) inserted directly adjacent to Farid’s verses.22

- Context: Where Farid expresses extreme asceticism or pessimism (e.g., ripping one’s clothes in longing for God), the Gurus insert a comment to balance it with optimism and the concept of finding God within the home/family life (Grhastha).

- Example: Farid writes, “I will tear my clothes to tatters… to find my Beloved.” Guru Nanak responds in the very next line, “Why tear your clothes? The Lord is found within the home”.22 This creates a living theological conversation within the canon itself, accepting Farid’s devotion while refining his methodology.

5.2 Bhagat Bhikhan: The Controversy of Identity

There are two hymns in Raag Sorath attributed to Bhagat Bhikhan. Historical analysis presents a dichotomy regarding his identity:

- The Sufi View: Tradition often identifies him as Sheikh Bhikhan (d. 1574) of Kakori (near Lucknow), a learned Sufi scholar.24 Proponents of this view argue that the vocabulary and tone align with Islamic devotional submission. He was known as a scholar of the Qadiri order.

- The Vaishnav View: Some scholars, notably Macauliffe, argued he was a Hindu Bhakta from the same era, citing the use of the name “Hari” in the hymns.25

- Synthesis: Modern Sikh scholarship generally acknowledges the Sufi identification, noting that the use of “Hari” or “Ram” by Sufi poets in India was common cultural syncretism. The inclusion of a medieval Sufi scholar reinforces the Granth’s non-sectarian nature. His hymns speak of the “Divine Medicine” (Naam) for the disease of the soul, a metaphor common in both Sufi and Bhakti literature.

5.3 Bhagat Sadhana: The Qasai (Butcher)

Bhagat Sadhana was a Muslim butcher by profession, a vocation considered “unclean” by orthodox Hindu standards and potentially lowly by aristocratic Islamic standards of the time. He contributed one hymn in Raag Bilaval.27

- Significance: His presence in the Granth is a radical statement on social equality. Despite his trade involving slaughter, his spiritual elevation is recognized. His hymn references his plea to God for protection, using the metaphor of a boat crossing the ocean of existence, and alludes to his persecution by a king.28 His tomb in Sirhind is a site of reverence.

5.4 The Case of Bhai Mardana

Bhai Mardana (1459–1534), the lifelong Muslim companion and rebeck player for Guru Nanak, is a central figure in Sikh history. There are three sloks in Raag Bihagara (Var of Bihagara) titled Mardana 1.29

- Authorship Controversy: Scholars are divided on whether these were written by Mardana or addressed to Mardana by Guru Nanak.

- View A: They are Guru Nanak’s words using Mardana as a persona or addressee to teach a lesson against the intoxication of wine, contrasting it with the intoxication of the divine Name.29

- View B: They are Mardana’s own compositions, approved and corrected/commented upon by Guru Nanak.

- Textual Evidence: The heading “Salok Mardana 1” usually implies the author is the First Guru (Nanak) speaking as or to Mardana. However, the distinct voice of the devotee is evident.

- Significance: Regardless of direct authorship, the presence of Mardana’s name in the canon canonizes the Muslim minstrel’s spiritual status. It affirms that the first Sikh (student) of the Guru was a Muslim, establishing the faith’s pluralistic foundation from its very inception.30

5.5 Satta and Balvand: The Muslim Minstrels

Rai Balvand and Satta Doom were Muslim rababis (musicians) who served Guru Angad through Guru Arjan. They co-authored the Ramkali Ki Var (also known as Tikke Di Var), which appears on Ang 966.31

- Historical Context: This Var is historically crucial as it documents the coronation and legitimacy of the first five Gurus, describing the transfer of the divine light from Nanak to Angad and so on. They used Islamic terminology like Ars (Throne) and Nur (Light).33

- Redemption Arc: History records that Satta and Balvand became arrogant and left the Guru’s service, only to suffer leprosy and poverty. Upon their repentance, they were forgiven, and their hymn of praise was included in the Granth—a testament to the power of repentance and the Sikh rejection of lineage-based superiority. They are referred to as “Doom,” a term for a low-caste bard community, yet their work is Gurbani.9

5.6 Bhagat Kabir: The Liminal Mystic

While Bhagat Kabir is often claimed by Hindus, his origins are deeply tied to the Muslim weaver (Julaha) community. Snippets mention his Muslim step-mother and his upbringing in a Muslim household.15 Kabir’s poetry in the Granth (541 hymns) is fiercely iconoclastic, rejecting the Vedas and the Quran alike in favor of a direct experience of God. He represents the synthesis where religious labels dissolve.

Chapter 6: Linguistic and Theological Synthesis

6.1 Intertextuality and Universalism

The “Muslim” contributions are not isolated in a “Muslim section.” They are interwoven with the hymns of Hindu Bhagats and Sikh Gurus within the Raags. A Shabad by Kabir (of Muslim upbringing) may follow one by Guru Nanak, followed by one from Ravidas. This structural integration physically manifests the theological claim that the “Truth” is one, though paths may vary.

6.2 God in the Granth

The definition of God in the SGGS blends the monotheistic transcendence common in Islam with the immanence found in Bhakti traditions. God is Allah, Ram, Hari, Parbrahm, and Khuda. The Mool Mantar (Root Formula) defines God as Nirbhau (Without Fear) and Nirvair (Without Enmity).35 This lack of enmity extends to the scripture’s embrace of diverse authors. The Guru Granth Sahib explicitly states:

“Some call Him Ram, some call Him Khuda… Some bathe at Hindu pilgrim places, some perform Hajj… Says Nanak, whoever realizes the Will of the Lord, he alone knows the secret.” (Ang 885)

Conclusion

The Sri Guru Granth Sahib is a literary and spiritual marvel that defies the conventional boundaries of religious texts. Historically, it is the only major scripture compiled and authenticated by the founders of the faith themselves. Structurally, it is a masterpiece of musical organization, prioritizing emotional resonance and aesthetic beauty through the Raag system. Theologically, it is a radical experiment in pluralism. By canonizing the works of Sheikh Farid, Bhagat Bhikhan, and the “low-caste” cobbler Ravidas alongside the Sikh Gurus, the Granth Sahib deconstructs the barriers of caste, creed, and religious origin. It stands not merely as a book for Sikhs, but as a shared heritage of South Asian spirituality, preserving the voices of the medieval saints who sang of a God beyond rituals and boundaries.

Thematic Epilogue: The Scripture of Universal Harmony

The final analysis of the Guru Granth Sahib reveals a scripture that was centuries ahead of its time in addressing the fractures of human society. In an era riven by sectarian violence between Mughal orthodoxy and rigid Hindu caste systems, the Guru Granth Sahib proposed a “Third Path”—one of humanity (Manas ki jaat sabai ekai pahchanbo).

The incorporation of authors from diverse backgrounds—Muslim Sufis, Hindu Bhaktas, and Court Poets—is not a historical accident but a theological necessity for a faith claiming universality. By bowing to the Granth, a Sikh bows not only to the memory of Guru Nanak but also to the wisdom of a Muslim Sufi (Farid) and a Dalit saint (Ravidas). This act of reverence performs a daily annihilation of the ego of caste and religious superiority.

Ultimately, the Guru Granth Sahib serves as a roadmap for interfaith harmony. It does not seek to convert the Muslim to a Hindu or the Hindu to a Muslim, but urges the Muslim to be a “true Muslim” (as defined by Farid’s piety) and the Hindu to be a “true Hindu” (abandoning empty ritual). It posits that the “Religion of Truth” is found in the content of one’s character and the sincerity of one’s devotion, regardless of the label one wears. In this sense, the Shabad Guru remains a potent, living force for global coherence, offering a sanctuary where diverse voices harmonize in the praise of the Singular Divine.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Here is an English translation of Guru Granth Sahib:

Leave a comment