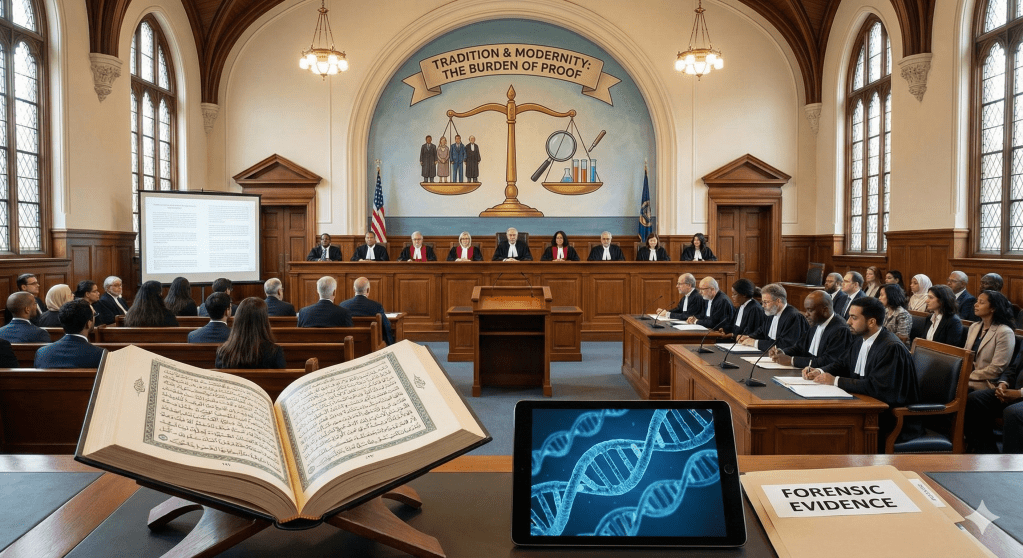

Epigraph

He sends water from the sky that fills riverbeds to overflowing, each according to its measure. The stream carries on its surface a growing layer of froth, like the froth that appears when people melt metals in the fire to make ornaments and tools: in this way God illustrates truth and falsehood–– the froth disappears, but what is of benefit to man stays behind–– this is how God makes illustrations. (Al Quran 13:17)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

The legal mechanism of inheritance serves as the fundamental DNA of social structure, dictating the transmission of power, wealth, and status across generations. For centuries, the Atlantic World was dominated by the twin feudal pillars of primogeniture—the exclusive right of the eldest son to inherit the family estate—and entail, which rendered such estates inalienable and indivisible. Rooted in a complex synthesis of Biblical exegesis, particularly the Mosaic “double portion,” and the martial necessities of medieval feudalism, this system calcified a landed aristocracy in Europe and its American colonies. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the pre-Jeffersonian inheritance systems, tracing their theological origins in the Hebrew Bible and their socioeconomic manifestations in Colonial Virginia. Furthermore, it explores the radical intervention of Thomas Jefferson, who, fueled by Enlightenment rationalism and a comparative legal study that included a profound engagement with the Qur’an and Islamic Law (Faraid), dismantled this ancient hierarchy. The report posits that while Jefferson’s primary drive was republican leveling, his legal commonplace books and library holdings reveal an acute awareness of the Islamic alternative—a system explicitly designed to fragment wealth through fixed fractional shares—offering a striking counter-model to the monolithic accumulation favored by English Common Law. Through a detailed examination of Biblical text, Quranic verses, colonial case law, and the economic decline of Virginia’s great dynastic families post-1785, this study illuminates how the shift from dynastic preservation to partible inheritance reshaped the trajectory of American democracy.

Part I: The Theology of the Firstborn — Biblical Foundations of Primogeniture

To understand the tenacity of primogeniture in the Western legal tradition, one must look beyond mere economic utility to its profound theological and anthropological roots. The practice was not merely a legal convenience but a cultural imperative sanctioned by the perceived will of the Divine. In the ancient Near East, and subsequently in the Judeo-Christian tradition, the firstborn male (bekhor) was not simply a biological occurrence but a bearer of cultic and familial sovereignty. The system of primogeniture was a deep-rooted mechanism recognizing the firstborn’s unique role, blending cultural expectation, family law, and religious duty, though the biblical narrative itself introduces a complex tension where this legal norm is frequently subverted by God’s sovereign choice.1

The Mosaic Mandate and the Double Portion

The central legal text underpinning the rights of the firstborn is found in the Deuteronomic Code. Unlike modern Western conceptions of equality, the Biblical worldview operated within a strict hierarchy of holiness and election. The firstborn was seen as the physical manifestation of the father’s vitality, the “beginning of his strength” (reshit ono).1

The Mosaic law is explicit regarding the material entitlement of the eldest son. Deuteronomy 21:15-17 addresses a scenario of polygyny or a “hated” wife, ensuring that the legal rights of the firstborn are not subject to the emotional whims of the patriarch. This law was crucial because it removed the distribution of the estate from the realm of affection and placed it firmly in the realm of divine law:

“If a man has two wives, the one loved and the other unloved, and both the loved and the unloved have…sourcestatus of the firstborn is an objective fact of birth order, ordained by God, not a subjective choice of the father.3 The law presupposes that fathers might be tempted to elevate the son of a favorite wife (as Jacob did with Joseph), but the law forbids this caprice in the distribution of the “right of the firstborn” (mishpat ha-bekhorah).

- Material Supremacy: The entitlement to a double share effectively ensured that the eldest son would possess the economic leverage to maintain the family’s standing. In an agrarian society, the fragmentation of land was the surest path to poverty. By giving the eldest son a double portion (two shares where others received one), the law concentrated capital in the hands of a single successor who acted as the executor and protector of the clan.1

The Divine Claim: Sanctification and Cultic Duty

The privilege of the firstborn was inextricably linked to heavy religious obligations. The Bible introduces a concept of “Divine Claim,” where the first issue of the womb belongs inherently to Yahweh. This concept is dramatized in the narrative of the Exodus, where the final plague kills the firstborn of Egypt while sparing Israel, creating a perpetual debt of gratitude and sanctification. The deliverance of the Israelite firstborn created a bond of ownership between God and the eldest male:

“Sanctify unto me all the firstborn, whatsoever openeth the womb among the children of Israel, both of man and of beast: it is mine.” (Exodus 13:2).2

This claim was not abstract. It required the “redemption” of the firstborn son through a ritual sacrifice or payment, known as Pidyon HaBen in later Judaism. The text in Exodus 13:14-16 explains that this ritual serves as a perpetual memorial of the deliverance from Egypt. Because God claimed the firstborn, they were originally intended to be the priestly class of the nation, the intermediaries between the family and the Divine. Although this duty was later transferred to the tribe of Levi following the Golden Calf incident (Numbers 3:12), the concept that the firstborn possessed a unique holiness remained embedded in the cultural psyche. They were the natural leaders of family worship and the custodians of the family’s spiritual heritage.2

In the pre-Mosaic narrative, this distinction is evident in the story of Cain and Abel. Genesis 4:4 notes that God had regard for Abel and his offering—”the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof”—emphasizing that the first is the portion worthy of the Divine. The logic follows that if the firstfruits of the harvest and the firstlings of the flock belong to God, so too does the firstborn son hold a status of being “set apart”.2 Consequently, when this theological framework was transposed onto property law, it imbued the inheritance rights of the eldest son with a sacred quality. To deprive the firstborn was not merely a civil tort; it was a violation of a divinely established order.

Patriarchal Nuance: Divine Sovereignty vs. Legal Custom

Despite the strictures of the law, the Biblical narrative contains a powerful counter-theme: the subversion of primogeniture by Divine election. The narrative arc of Genesis is replete with younger sons who supersede their elders, suggesting that while the law favors the firstborn, God’s grace and covenant often bypass them. This created a complex theological inheritance for later Christian societies, which had to reconcile the legal rule with the spiritual narrative.

- Isaac over Ishmael: Though Ishmael was the biological firstborn of Abraham, born of Hagar, he was excluded from the covenantal inheritance in favor of Isaac, the younger son born of Sarah. This established the precedent that spiritual status could override biological priority.5

- Jacob over Esau: The most famous subversion involves Esau selling his birthright (bekhorah) for a “mess of pottage” (lentil stew). This transaction (Genesis 25:29-34) demonstrates that while the right was hereditary, it was also a commodity that could be alienated by the unworthy. Esau is depicted as despising his birthright, prioritizing immediate physical gratification over long-term dynastic responsibility. Later, Jacob secures the blessing of the firstborn through deception, yet God ratifies this transfer, declaring “Jacob I have loved, but Esau I have hated” (Malachi 1:2-3).2

- Joseph over Reuben: Reuben, the firstborn of Jacob, forfeits his birthright through sexual immorality (sleeping with his father’s concubine, Bilhah). The double portion—the right of the firstborn—is then transferred to Joseph, the firstborn of the beloved wife Rachel. This is legally codified in 1 Chronicles 5:1, which states explicitly that the birthright was given to the sons of Joseph.

- Ephraim over Manasseh: In Genesis 48, Jacob deliberately crosses his hands to bless the younger grandson, Ephraim, over the firstborn, Manasseh. When Joseph attempts to correct his father, Jacob refuses, declaring that while Manasseh will be great, the younger brother “shall be greater than he, and his seed shall become a multitude of nations”.1

These theological exceptions provided a nuance that Thomas Jefferson and other reformers would later exploit. While the rule of primogeniture was Biblical, the narrative of the Bible frequently celebrated the triumph of merit and divine favor over the accident of birth. However, for centuries in Europe, the legal rigidity of Deuteronomy 21 prevailed over the narrative flexibility of Genesis.5

Part II: The Atlantic Transposition — Entail and the Virginian Aristocracy

When English settlers established the colony of Virginia, they imported the legal architecture of the mother country, attempting to replicate the stability and hierarchy of the English gentry. The two pillars of this system were Primogeniture (inheritance by the eldest) and Entail (the restriction of sale). This legal transposition was not merely administrative; it was an attempt to graft the feudal social order onto the American wilderness.

The Mechanics of Fee Tail (Entail)

While primogeniture directed who inherited, the entail (fee tail) dictated how they held the land. An estate held in “fee tail” was not owned by the occupant in the modern sense of fee simple (absolute ownership). Rather, the occupant was merely a life tenant. He could enjoy the fruits of the land (usufruct) during his lifetime, but he could not sell it, mortgage it beyond his lifespan, or divide it. Upon his death, the land automatically passed to the next heir in the “tail” (usually the eldest son).7

This legal device was designed to prevent the “dissipation” of wealth. A spendthrift heir could not squander the family legacy, nor could a compassionate father divide the land to provide for younger children. The estate was legally frozen in time, preserving the family name and political power in perpetuity.10 The concept was explicitly feudal, originating in the Statute De Donis Conditionalibus (1285), which allowed English lords to lock their land into a specific line of descent to ensure that the estate remained intact to support the military service owed to the Crown.4

In Virginia, the practice of entail was even more rigid than in England. In England, a legal fiction known as a “common recovery” allowed heirs to “dock” (break) an entail, converting it to fee simple. This provided a safety valve for the market. In Virginia, however, the colonial legislature strictly guarded entails. To break an entail required a specific private act of the General Assembly, a difficult and expensive process usually reserved for swapping parcels of land rather than dissolving the estate.7 This rigidity meant that Virginia’s “aristocracy” was artificially propped up by the state, shielded from the economic consequences of their own mismanagement or the natural fragmentation of families.

The Socioeconomic Landscape of the “First Families”

The combination of primogeniture and entail created a distinct class structure in Virginia, dominated by a few interrelated families—the “First Families of Virginia” (FFV)—such as the Carters, Lees, Randolphs, and Byrds. These families controlled the Council, the House of Burgesses, and the vast majority of the colony’s prime tobacco lands.11

The Carter Dynasty (“King” Carter)

Robert “King” Carter (1663–1732) exemplifies the accumulation made possible by this system. As a younger son himself, he inherited a modest portion but leveraged his position as a land agent for the Fairfax proprietary to amass 300,000 acres. Upon his death, although he provided for his younger sons, the bulk of his political weight and prime estates were structured to ensure the continued dominance of the Carter line. The system allowed the accumulation of capital (slaves and land) on a scale that mimicked the British aristocracy. His estate at Corotoman and the massive landholdings in the Northern Neck effectively functioned as a principality, governed by the laws of inheritance he set in motion.12

The Plight of the Younger Son

The shadow of primogeniture created a specific sociological phenomenon: the “younger son.” In England, younger sons of the gentry often went into the clergy, the military, or the law. In the colonies, they became pioneers. Many of the early Virginians were themselves younger sons of English gentry who, cut off from the family estate by primogeniture, sought their fortunes across the Atlantic.6 This “Cavalier” migration brought with it a cultural commitment to recreating the system that had excluded them—they wanted to be the patriarchs of new lines, establishing their own primogeniture.11

This dynamic repeated within the colony. Younger sons of the Virginia elite, unable to inherit the main plantation, were often pushed westward or southward to claim new lands. This fueled the expansion of the frontier but also created a class of “gentlemen” with aristocratic tastes but precarious finances.

- George Washington: A prime example of the system’s caprice. As a younger son of Augustine Washington’s second marriage, George inherited the modest Ferry Farm, while his older half-brother Lawrence inherited the prime estate, Mount Vernon (an estate named after an English admiral, reflecting the Atlantic ties). Under strict primogeniture, George would have remained a minor surveyor and small planter. He only acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence’s death and the subsequent death of Lawrence’s only child—a twist of fate, not the design of law.14

- William Byrd II: Inherited the massive Westover estate and political clout, while his siblings were left in comparative obscurity, dependent on his largesse. The “Black Swan of Westover” lived a life of London luxury and intellectual pursuit, supported by the undivided revenues of his inherited estate, while younger branches of the family slipped into the middling classes.12

Economic Stagnation and Debt

By the mid-18th century, the system began to show cracks. Entail prevented land from being used as collateral for debts. Since the “tenant in tail” did not fully own the land, creditors could not seize it to satisfy loans. This protected the land but strangled credit markets. Planters were “land rich but cash poor,” living in opulent houses they could not sell, serviced by enslaved laborers they could not liquidate without dismantling the estate’s workforce. The “dead hand” of the past paralyzed the economic dynamism of the present, leading to a mounting debt crisis among the Virginia gentry that would eventually feed the revolutionary fervor against British credit restrictions.7

Part III: The Islamic Counter-Model — Faraid and the Fragmentation of Wealth

While Europe solidified the consolidation of wealth through primogeniture, the Islamic world operated under a radically different legal paradigm regarding inheritance. Known as ‘Ilm al-Faraid (The Science of Shares), Islamic inheritance law is derived explicitly from the Qur’an and stands in stark contrast to the principle of primogeniture. This system, detailed in the 7th century, presented a legal framework that seemed designed to prevent the very accumulation of dynastic wealth that English law sought to preserve.

Quranic Injunctions: The Anti-Accumulation Mandate

The primary verses governing inheritance are found in Surah An-Nisa (Chapter 4), verses 7, 11-12, and 176. These verses are detailed, mathematical, and mandatory, leaving almost no room for the testamentary whim of the deceased.

“From what is left by parents and those nearest related there is a share for men and a share for women, whether the property be small or large,—a determinate share.” (Quran 4:7).17

The Quran explicitly rejects the pre-Islamic Arab practice (similar to primogeniture) where only those capable of bearing arms (males) inherited. Instead, it mandates a fractional distribution among a wide circle of heirs:

“Allah instructs you concerning your children: for the male, what is equal to the share of two females. But if there are [only] daughters, two or more, for them is two-thirds of one’s estate. And if there is only one, for her is half. And for one’s parents, to each one of them is a sixth of his estate if he left children…” (Quran 4:11).18

Key distinctions from Primogeniture:

- Rejection of Primogeniture: The eldest son has no special status over the youngest son. All sons inherit equally. The concept of “birthright” in the sense of priority is alien to the Quranic system.19

- Inclusion of Females: Daughters, mothers, and wives have guaranteed fixed shares (furud). While a daughter typically receives half the share of a son (based on the rationale that men bear the financial burden of the family, providing dowry and maintenance), she cannot be disinherited. This ensured that property flowed laterally to women, not just vertically through men.20

- Mandatory Fragmentation: A Muslim cannot will away his entire estate to a single heir. Bequests (wasiyya) are limited to one-third of the estate, and crucially, they cannot be made in favor of a legal heir (who already has a fixed share). The remaining two-thirds must be divided according to the Quranic fractions. This prevents a father from disinheriting a “disfavored” son or piling all wealth onto a favorite.21

The Economic Consequences: The Kuran Thesis

Economist Timur Kuran has argued extensively that this inheritance system was a primary driver of the “Long Divergence” between the economic development of the Middle East and the West.23

Under primogeniture, capital remained consolidated. A large estate remained a large estate, allowing for long-term capital accumulation, investment in large-scale ventures, and the survival of business continuity across generations. The estate was a corporate entity that survived the individual.

Under Islamic law, a large merchant’s wealth was immediately fragmented upon his death. If a wealthy merchant died leaving a wife, three sons, and two daughters, his business capital was legally divided into eight distinct shares (wives get 1/8, the rest divided among children with 2:1 ratio). This constant fragmentation meant that businesses rarely outlived their founders. It prevented the emergence of long-standing “aristocratic” merchant families with the capital reserves to challenge the state or fund industrialization.23

While waqf (endowments) provided a mechanism to lock up assets for charitable (and sometimes family) use, circumventing some fragmentation, the underlying logic of Faraid was one of redistribution. It circulated wealth through the community rather than preserving it in a vertical lineage.26 This system created a society that was more egalitarian in its distribution of capital but less capable of sustaining the massive concentrations of private wealth required for early capitalism—a trade-off that Jefferson, with his antipathy toward “monied corporations” and preference for agrarian equality, would likely have found philosophically intriguing.

Part IV: Thomas Jefferson’s Intellectual Encounter

In 1765, eleven years before he penned the Declaration of Independence, a 22-year-old law student named Thomas Jefferson purchased a two-volume English translation of the Qur’an from the office of the Virginia Gazette in Williamsburg.28 This copy was the 1764 edition of George Sale’s 1734 translation, titled The Koran, Commonly Called the Alcoran of Mohammed.

“Sale’s Koran” and the Study of Comparative Law

Jefferson did not read the Qur’an merely as a religious curiosity; he engaged with it as a law book. In his library catalog, he shelved the Qur’an not under “Religion” but under “Religion/Jurisprudence,” alongside Greek and Roman legal texts.30 This categorization is critical. For Jefferson, the Qur’an was a code of law governing a civilization, comparable to the Justinian Code or the English Common Law.

George Sale was a lawyer by training, and his “Preliminary Discourse” to the translation was a massive, scholarly treatise on Arab history, customs, and law. Sale explicitly compared Islamic law to Jewish and Roman law, providing Jefferson with a comparative legal framework.30 Section VI of the Preliminary Discourse is dedicated to civil laws, including a detailed explanation of inheritance. Sale notes:

“The laws of inheritance… are laid down in the fourth chapter of the Koran… and are so particular and full, that there is no room left for the discretion of the executors.”

In his Literary Commonplace Book and Legal Commonplace Book, Jefferson made copious notes on his readings. While direct notes on Islamic inheritance in his handwriting are sparse compared to his notes on English law, the intellectual influence is discernible through his engagement with authors like Pufendorf and Voltaire, who commented on Islamic customs.32 Jefferson’s notes show he was actively searching for universal principles of “natural law” and was willing to look beyond Christendom to find them.

The Key Insight: Jefferson was obsessively concerned with the “natural law” of property. He sought alternatives to the feudal model. In the Islamic system, described in detail by Sale, Jefferson saw a functioning legal system—one governing a vast empire—that explicitly forbade the very thing Jefferson hated most: the accumulation of wealth in select families through primogeniture.

Sale’s translation of Surah 4 explained the intricate division of property. For a mind like Jefferson’s, searching for a “natural” way to distribute property that favored republican equality over aristocratic preservation, the Quranic model offered a stark, successful counter-proof to the English dogma that primogeniture was the only stable way to manage society. It demonstrated that a civilization could function by breaking up estates rather than preserving them.34

The “Aristocracy of Virtue”

Jefferson famously argued against the “artificial aristocracy” founded on wealth and birth, advocating instead for a “natural aristocracy” of virtue and talent.36 He believed that the English system of entail and primogeniture artificially propped up the former. By studying systems like the Islamic one, alongside Saxon and Roman models, Jefferson gathered the intellectual ammunition to argue that the English system was not “natural law” but a feudal corruption.

While Jefferson likely did not seek to adopt Islamic law (which contained elements he would have rejected, such as polygyny), the existence of the Islamic inheritance model served as a powerful dialectical tool. It proved that the “rights of the firstborn” were not universal divine mandates but specific cultural constructions that could be legislated away. The Quranic injunction against hoarding wealth and its mandate for distribution resonated with Jefferson’s republican ideal of a broad base of small landholders.

Part V: The Revolution in Inheritance — The Reforms of 1776 and 1785

Upon returning to Virginia from the Continental Congress in 1776, Jefferson immediately launched an assault on the legal foundations of the Virginia gentry. He viewed the Revolution not just as a break from King George III, but as a break from the “feudal system” that sustained the local aristocracy.

The Abolition of Entail (1776)

In October 1776, Jefferson introduced a bill in the Virginia General Assembly to abolish entails. His logic was explicitly anti-aristocratic:

“In the earlier times of the colony… some provident individuals procured large grants; and, desirous of founding great families for themselves, settled them on their descendants in fee tail… To annul this privilege, and instead of an aristocracy of wealth… to make an opening for the aristocracy of virtue and talent… was deemed essential to a well-ordered republic.” (Jefferson’s Autobiography).36

The “Act declaring tenants of lands or slaves in taille to hold the same in fee simple” converted all entailed estates into fee simple estates.38 This meant that the current owner of a vast plantation legally became its absolute owner. Crucially, this allowed him to sell it or divide it. It unlocked the “frozen” capital of the Virginia aristocracy, making land a commodity rather than a dynastic trust.

Jefferson faced stiff opposition from Edmund Pendleton, a conservative jurist and leader of the “aristocratic” faction. Pendleton proposed a compromise: allow the tenant to break the entail if he chose, but leave the default in place. Jefferson refused, insisting on total abolition. He argued that the earth belongs to the living, and the dead have no right to control the land of the living.36

The Statute of Descents (1785)

The final blow to the old order came with the Statute of Descents, passed in 1785 (though drafted by Jefferson years earlier). This act abolished primogeniture entirely.40

Jefferson drafted the law to ensure that if a person died intestate (without a will), their property would be divided equally among all children, regardless of sex or birth order.

“To the surviving spouse of the decedent… two-thirds of the estate descends and passes to the decedent’s children and their descendants, and one-third of the estate descends and passes to the surviving spouse.”.41

This was a radical departure. In English law, real estate went to the eldest son; personal property was divided. Jefferson unified them and applied the principle of partible inheritance.

The Islamic Parallel:

While Jefferson did not cite the Quran in the text of the bill, the structural similarity to the Islamic refutation of primogeniture is profound.

- English Law: 100% to eldest son.

- Islamic Law: Fractional shares to all children (2:1 male/female ratio).

- Jefferson’s Law: Equal shares to all children (1:1 ratio).

Both systems function as mechanisms of entropy against wealth concentration. They both ensure that a massive estate, within two or three generations, is pulverized into smaller, more egalitarian holdings unless active steps (like buying out siblings) are taken. Jefferson essentially radicalized the “fragmentation” principle found in comparative systems like Islam to serve a republican end. By studying the Quran, Jefferson saw that a legal code could actively engineer social structure through inheritance math.

Part VI: The Fall of the House of Usher — Post-Reform Virginia and the Decline of the Gentry

The impact of Jefferson’s reforms was not immediate, but it was inexorable. Within two generations, the massive dynastic estates of colonial Virginia began to disintegrate.

The Fragmentation of Estates

The Carter Family: The descendants of “King” Carter saw their dominance evaporate. Robert Carter III, heavily influenced by religious non-conformity (Baptist) and the new republican spirit, utilized a “Deed of Gift” in 1791 to manumit hundreds of slaves, further dismantling the capital basis of his estate.43 By the 19th century, the vast Carter lands were parcelled out among numerous heirs. What was once a single dominion was now a patchwork of smaller farms. The “King” was dead, and his kingdom was partitioned.

The Lee Family (Stratford Hall): The magnificent Stratford Hall estate passed to Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee (a cavalry hero and father of Robert E. Lee). However, the abolition of entail meant he could—and did—mortgage the property to speculate in land. Without the legal protection of entail, his bad business decisions led to financial ruin. He was imprisoned for debt, and Stratford Hall passed out of the Lee line, sold to cover debts.45 This would have been legally impossible under the old pre-1776 laws, where the land would have been protected from the creditors. Robert E. Lee was born at Stratford but grew up in genteel poverty in Alexandria, a direct result of the liquidity and vulnerability introduced by Jefferson’s reforms.46

The Randolphs: The Randolphs of “Wilton” and “Turkey Island” faced similar declines. By the time of John Randolph of Roanoke, the family was fracturing under the weight of debt and division. John Randolph, eccentric and bitter, lamented the decline of the “old gentry,” blaming the democratic leveling that destroyed the social fabric of his youth.47 He saw the abolition of primogeniture as the death knell of Virginia’s leadership class, predicting that without large estates, there would be no leisure class to study statecraft.

The Irony of Slavery

While Jefferson hoped that breaking up large estates would create a yeoman republic of small farmers, the abolition of entail had a dark side regarding slavery. When land was entailed, the enslaved people attached to the land were often entailed with it—they could not be sold off separately. They lived in settled communities on the same land for generations.

When entail was abolished, slaves became liquid assets. As estates fragmented and heirs faced debts (no longer protected by entail), the easiest way to raise cash was to sell human beings. This fueled the domestic slave trade, moving enslaved Virginians to the cotton fields of the Deep South.7 The democratization of land ownership for whites inadvertently commodified Black lives more aggressively, as “heirs’ property” disputes often resulted in the liquidation of the estate’s “assets”—human beings—to satisfy the equal division required by the new Statute of Descents.50

Epilogue: The Architecture of Inheritance

The abolition of primogeniture stands as one of the most significant, yet understated, revolutions in American history. Before Thomas Jefferson, the trajectory of American society was set toward a replication of European feudalism, with vast estates acting as quasi-independent principalities governed by hereditary lords.

By dismantling this system, Jefferson utilized a form of legal engineering that resonated with the anti-accumulation principles found in Islamic Law. Whether direct or indirect, the insight that inheritance laws define the political structure is shared by both the Quranic revelation and the Jeffersonian statute. The Quran shattered the tribal concentration of wealth to foster a community of believers (Ummah) bound by faith rather than lineage. Jefferson shattered the feudal concentration of wealth to foster a republic of citizens bound by virtue rather than birth.

However, the transition was not without cost. The stability of the old order was replaced by the volatility of the market. The “First Families” fell, not to the guillotine as in France, but to the slow attrition of division and debt. In their wake, a more dynamic, chaotic, and democratic society emerged—one where the “firstborn” held no scepter, and the “aristocracy of virtue” was free to rise, or fall, on its own merits.

Statistical Appendix: Comparative Inheritance Models

| Feature | English Common Law (Pre-1776) | Islamic Law (Faraid) | Jefferson’s Statute (1785) |

| Primary Beneficiary | Eldest Son (Primogeniture) | Fractional shares for all children | Equal shares for all children |

| Female Rights | Excluded if male heir exists | Guaranteed fixed share (approx. 1/2 of male) | Equal share to males |

| Estate Integrity | Preserved via Entail | Fragmented (Anti-accumulation) | Fragmented (Partible inheritance) |

| Spousal Share | Dower (Life interest in 1/3) | Fixed share (1/8 or 1/4) | Fee simple share (1/3) |

| Testamentary Freedom | Full (can disinherit via will) | Limited (Max 1/3 bequests) | Full (can disinherit via will) |

| Socioeconomic Result | Concentration of Wealth (Aristocracy) | Circulation of Wealth (Egalitarian/Fractured) | Broad Distribution (Republicanism) |

Table 1: A comparative analysis of inheritance systems showing the structural alignment between Islamic mechanics and Jeffersonian goals against the English model.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that Thomas Jefferson’s assault on primogeniture was the result of a deliberate, comparative legal inquiry. He recognized that the “Biblical” defense of primogeniture was largely a feudal construct, distinct from the nuanced narratives of the Patriarchs. In his search for a legal solvent to dissolve the “artificial aristocracy,” he found intellectual solidarity in the legal codes of the non-Christian world, including the detailed inheritance mathematics of the Qur’an. By adopting the principle of partible inheritance, America diverged from its English roots, embarking on a socioeconomic experiment that mirrored the “fragmentation” inherent in Islamic law, fundamentally altering the landscape of wealth and power in the New World.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment