Presented by Zia H Shah MD, the Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Islamic tradition holds that God (Allah) sent messengers and prophets to every people, even if not all are named in the Qur’an. The Qur’an repeatedly affirms that “to every community a messenger was sent” (e.g. Qur’an 10:47) and that “We certainly sent among every people a warner”academia.edu. A well-known hadith (though of disputed authenticity) even speaks of 124,000 prophets sent throughout historyacademia.edu. This universalist view has led some Muslim thinkers to suggest that figures like Buddha or Confucius – founders of major spiritual traditions – may correspond to unnamed prophets or messengers of God. For example, modern scholar Imtiyaz Yusuf cites the Qur’an: “We sent messengers before you, some We have mentioned, and others We have not mentioned” (Q40:78) and notes that God’s messengers all spoke the language of their peoplecrcs.ugm.ac.id. The classical jurist Reza Shah-Kazemi (2010) explicitly formulates premises based on such verses: for instance, that “every community has a special Messenger” (Q10:47) and that some prophets’ names are not revealed in scripture (Q4:164)academia.edu. These arguments are used by some 20th–21st century authors to support the idea of “unmentioned prophets” like Buddha. At the same time, mainstream Islamic scholarship emphasizes that only a limited number of prophets (25 by name in the Qur’an) are mentioned, while the rest remain unspecified by Allah’s willacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id.

Classical Islamic Scholarship

Early Muslim historians and exegetes encountered knowledge of Buddhism (through travel and trade) but generally did not explicitly identify Buddha by name as a prophet. For example, al-Ṭabarī (d. 923), in his History, reports the presence of Buddhist statues and monasteries (e.g. in Bukhara and Sindh)crcs.ugm.ac.id, but does not discuss the Buddha himself or classify him as a messenger of God. Later Islamic historians noted Buddhism as a religion: al-Maqdisī (10th c.), al-Bīrūnī (11th c.) and Ibn al-Nadīm (10th c.) all describe Buddhist beliefs and practices, often sympathetically, but they do so in general terms without naming the historical Buddhaacademia.eduacademia.edu. In Kitāb al-Milal wa al-Nihal (1153), al-Shahrastānī famously compares the Buddha to the Qur’anic figure Khidr (the “Green Man”); he portrays the Buddha as a seeker of wisdom akin to a prophet, though this identification is more metaphorical than literalacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id. In short, no classical Sunni tafsīr or ḥadīth source explicitly calls Gautama Buddha a prophet, though they acknowledge the existence of Buddhism and its early origins.

Similarly, classical works make almost no mention of Confucius. The Muslim geographers and historians of the medieval period generally had little information about pre-modern China, and none names Confucius as a prophet. (The Persian historian Rashīd al-Dīn Hamadānī in the 13th c. wrote introductions to various non-Islamic histories, but even he does not treat Confucius as a messenger of Allahcrcs.ugm.ac.id.) The Chinese Muslim scholars of later centuries (such as Wang Daiyü or Liu Zhi) who synthesized Islam and Confucianism did so by highlighting shared moral values, yet they did not present Confucius himself as an Islamic prophet. In sum, classical Islamic scholarship was silent on Confucius as a prophet, reflecting the historical lack of contact. (In fact, prominent early modern Muslim reformers like Rashīd Rida noted that Confucianism – like Buddhism and Hinduism – was omitted from the Qur’an simply because it was far removed from Arabiahts.org.za.)

Modern Muslim Perspectives

In the 20th and 21st centuries, some Muslim scholars and thinkers have explicitly addressed whether Buddha or Confucius might fit into the Islamic paradigm of prophethood or righteousness. On Buddha, a variety of opinions appear. Some modern traditionalist writers assert Buddha was indeed a prophet (though unnamed). For instance, the Indian Muslim jurist Ḥamīdullāh (d. 2002) and scholar Ḥamīd Abd al-Qādir (1895–1966) argued that the Qur’anic figure Ḏū al-Kifl could be identified with Siddhartha Gautama (since “Kifl” was linked etymologically to Kapilavastu, Buddha’s birthplace)hts.org.za. They also note that Sūrat al-Ṭīn (Q95) begins “By the fig and the olive…” and interpret at-tīn (the fig) as a possible reference to the Bodhi fig tree under which Buddha attained enlightenmenthts.org.zacrcs.ugm.ac.id. Shaykh Yūsuf al-Qāsimī (late 19th c.) went so far as to suggest the imagery of Sūrat al-Ṭīn symbolizes, among others, the Buddha’s enlightenmenthts.org.za. Likewise, contemporary authors like Shahab al-Dīn Ḥussaynī Kāzimī, Imtiyāz Yūsuf, and Hamza Yūsuf (b. 1958) entertain the notion that Buddha could be an “unmentioned prophet”academia.eduhts.org.za. They point to the Qur’anic principle that Allah “did not neglect a people without sending a warner to them” and interpret Buddhists as essentially followers of a prophetic traditioncrcs.ugm.ac.idacademia.edu. Many also classify Buddhists as akin to Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book) in modern exegetical frameworks, alongside Zoroastrians, Sabians, etc. For example, early-20th-century reformer Rashīd Rida explicitly included Buddhists (and Confucians) among the Ahl al-Kitāb, noting that such religions were simply unnamed in the Qur’an because Arabs of Muhammad’s time were unaware of themhts.org.za.

By contrast, most contemporary Sunni scholars stop short of proclaiming Buddha a full-fledged prophet of God. They may nevertheless regard him as a ṣāliḥ (righteous one) or a great teacher endowed with divine guidance in his own time. For instance, some view the Buddha’s teachings on compassion and monotheistic ethics as generally compatible with tawḥīd (though others, noting Buddhism’s non-theistic language, say he “did not deny God explicitly”academia.edu). What unites these views is acknowledgment that Allah’s mercy and truth reaches beyond Arabia. In sum, some modern Muslims accept the possibility that Buddha was a divinely sent reformer for his people (though not a law-bearing messenger like Moses or Muhammad)hts.org.zacrcs.ugm.ac.id.

On Confucius, the picture is more limited. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community – a modern movement founded in 1889 – explicitly holds that figures like Buddha, Krishna, and Confucius were prophets of God. Their founder, Mirzā Ghulām Aḥmad (d. 1908), taught that the essential teachings of Krishna, Buddha, Confucius (and others) converge with Islamthesanghakommune.orgalislam.org. (The Ahmadiyya officially recognizes Confucius among “the great religious founders and saints”alislam.org.) However, mainstream Sunni scholars do not make such claims for Confucius. Apart from noting general moral parallels, they do not list him as a prophet. Rashīd Rida’s view (quoted above) counts Confucians as Ahl al-Kitāb by extensionhts.org.za, but this is more a statement of tolerance than of actual prophethood. In practice, modern Muslim writers mostly regard Confucius as a revered sage or philosopher, not as a divine messenger.

Universal Prophethood and Prophetic Figures

Islamic theology emphatically teaches that Allah’s guidance was sent to all peoples. This is grounded in verses such as Quran 16:36 (“We sent a messenger to every people”) and in the Prophetic hadith traditions. The oft-quoted figure of 124,000 prophets (and 315 who were “great leaders”) comes from a hadith of the Prophet Muḥammadacademia.edu. (Scholars note this hadith is weak, but the notion is widely cited to emphasize the vast number of divinely guided people in history.) Classical commentators already interpreted the Qur’an to mean that “among every people was a prophet” – a point underscored by the Prophet’s words: “Whosoever Allah wants good for, He gives him understanding of the religion” (a wording implying understanding through prophets)academia.edu. In line with this, Muslim tradition often says explicitly that God did not leave any society without a warner. For example, Imtiyāz Yūsuf remarks that the Qur’an states “We have not sent a messenger except [speaking] in the language of his people”crcs.ugm.ac.id, meaning each nation received revelation in terms it could understand.

Because of this universal mission, Muslim scholars have considered how to classify non-Abrahamic religions. Many adopt a broad definition of Ahl al-Kitāb, extending it to any community that ever had scripture or regular prophetic guidance. Some modern thinkers (e.g. Rashīd Rida) even argued that the People of the Book could include Buddhists, Hindus, and Confucianshts.org.za, not because of an explicit Qur’anic text but for reasons of equity: those traditions emerged in distant lands unknown to the Arabs of Muhammad’s time. The idea is that Allah’s mercy encompasses even those faiths by giving them guidance suited to their people. Conversely, the hadith and Qur’an also make it clear that Muslims need not detail every prophet by name; it suffices that “We did not fail to send a messenger to every nation” in God’s wisdomacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id.

Quranic Allusions to Buddha and Confucius

No one claims that Buddha or Confucius appears literally by name in the Qur’an. Yet several indirect references have been proposed by Muslim exegetes:

- Dhul-Kifl: The Qur’an mentions Ḏū al-Kifl (31:48, 21:85), traditionally identified with the prophet Ezekiel or a righteous man in Israel. Modern Muslim writers like Ḥamīdullah and Ḥamīd Abd al-Qādir argue that Ḏū al-Kifl could instead refer to the Buddhahts.org.za. They base this on linguistic wordplay: kifl is linked to “Kapilā” or Kapilavastu (Buddha’s home). If accepted, then Buddha would be seen as a Qur’anic character albeit unnamed. This interpretation is not classical, but it is cited in contemporary comparative scholarshiphts.org.za.

- Sūrat al-Ṭīn (95:1–4): The chapter opens “By the fig and the olive, and Mount Sinai, and this secure city [Mecca]” (Q95:1–3). Some modern commentators (e.g. Yūsuf al-Qāsimī and Imtiyāz Yūsuf) read these symbols as representing great prophets: the olive for Jesus (‘Īsā), Sinai for Moses (Mūsā), the city for Muhammad, and the fig (Arabic at-tīn) as hinting at Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi tree (a fig species)hts.org.zacrcs.ugm.ac.id. In this view, the fig/“bodhi” symbolically stands for Siddhārtha’s awakening. While speculative, this interpretation has currency among some Muslim writers as a way to link the Qur’an to Buddhism’s founderhts.org.zacrcs.ugm.ac.id.

- Unmentioned Messengers: As noted, the Qur’an explicitly says “We did not neglect any community without sending a warner to it” (Q35:24) and that We mention only some of the messengers in scriptureacademia.edu. Scholars like Reza Shah-Kazemi stress that the Qur’an expects “unnamed prophets”academia.edu. Thus any wise reformer like Buddha or Confucius could fall into this category. Rashīd Rida’s point (cited above) is that the Qur’an’s verses on People of the Book (Q3:64–69, Q5:46) allow extension to any group with scripture or revelation, even if not explicit. In sum, while no explicit verses name Buddha or Confucius, Muslim thinkers draw on these general principles to suggest they could be among God’s hidden messengersacademia.eduhts.org.za.

Buddha and Confucius in Their Traditions

To assess these Islamic perspectives, it helps to recall how Buddha and Confucius are viewed in their own religions.

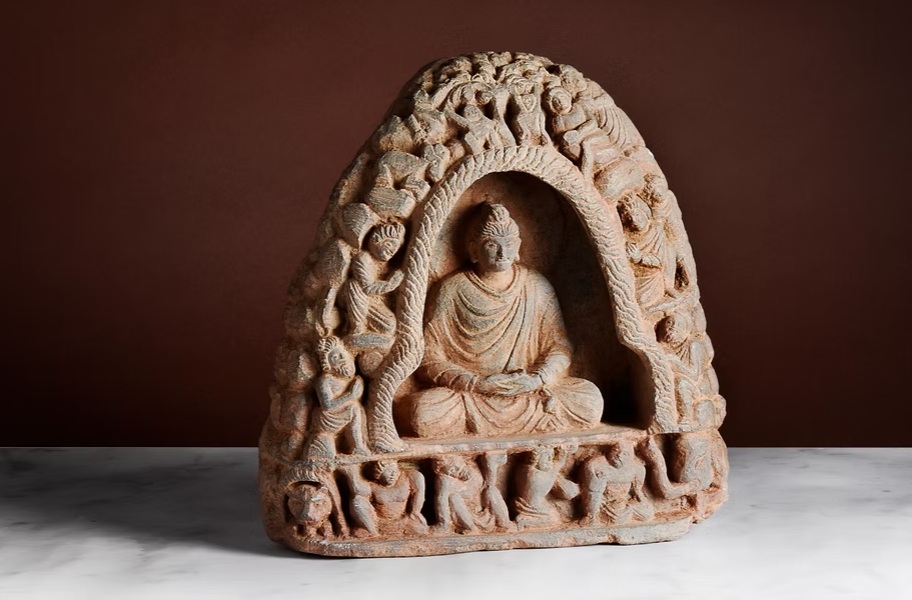

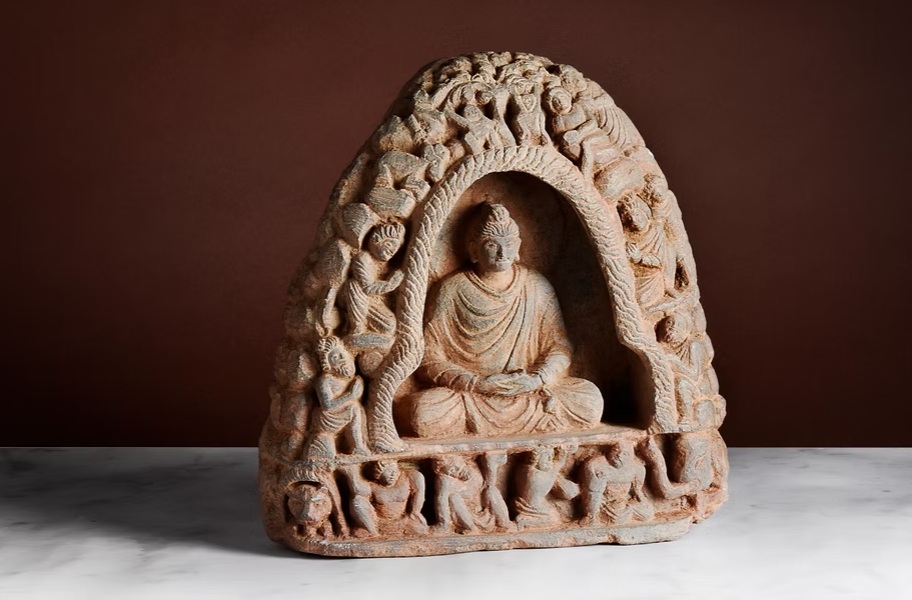

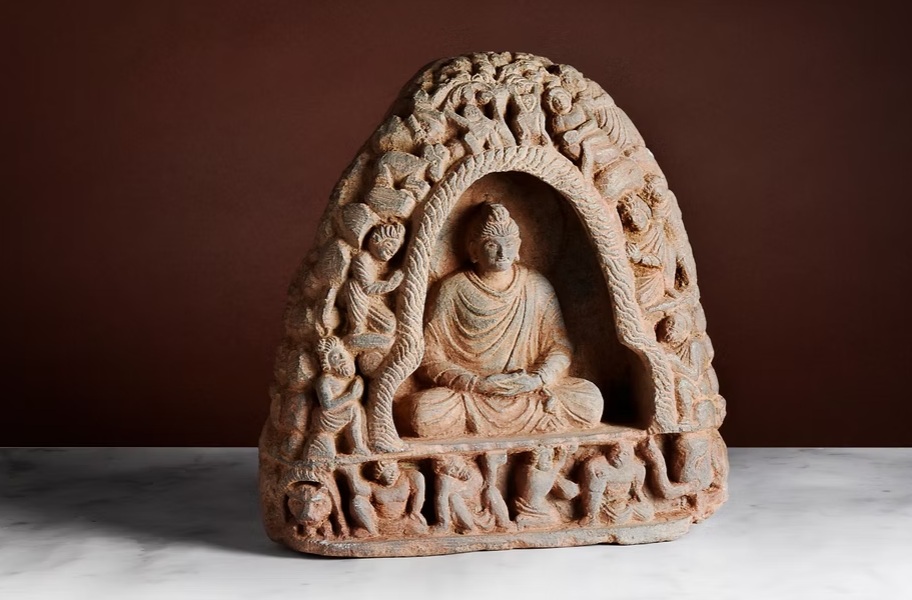

Buddhism holds that Siddhartha Gautama (c. 5th–4th century BCE) was a human enlightened teacher, not a god. He taught the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path as a way to end suffering (dukkha) through right belief and conduct. Early Buddhist scriptures do not present him as a divine prophet with a revealed Book; rather, he attained perfect insight (bodhi) through meditation and taught others. Hindu tradition, especially from the Puranic period onward, offers a different angle: in many Puranas Buddha is listed as the 9th avatar of Vishnudevdutt.com. However, even here the Hindu “Buddha” is portrayed not as the historical Guatama in a biographical sense, but as a divine incarnation who appeared to delude asuras (demons) and end animal sacrificesdevdutt.com. (As mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik explains, “for Buddhists, Buddha is not an avatar of Vishnu. For Hindus, he may be”devdutt.com.) Importantly, mainstream Buddhist tradition does not teach that the Buddha brought a new scripture from God or spoke as Allah’s messenger; to Buddhists he is “the awakened one,” and ultimate reliance is on the Dharma (law) he taught, not on divine revelation. Thus, equating Buddha with an Islamic prophet requires some interpretive flexibility. Muslim writers who do so typically emphasize the moral overlaps (monotheism, ethics) and universal truth, as noted aboveacademia.eduhts.org.za.

In Chinese tradition, Confucius is revered as the “Great Master” (Kong Fuzi) and spiritual ancestor of scholars, but not as a prophet of God.

Confucius (551–479 BCE) was an ancient Chinese sage whose teachings focused on ethics, family, and social harmony. He is traditionally credited with compiling or editing key texts (the Analects, Book of Odes, etc.), and his sayings form the foundation of Ru (儒) or Confucianism. The scholar Fung Yu-lan notes that Confucius is “the spiritual ancestor of later teachers… and countless others whose lives and works figure prominently in Chinese intellectual history”plato.stanford.edu. Importantly, Confucius taught li (ritual propriety) and ren (benevolence) and affirmed a moral order aligned with “Heaven” (Tian) but offered no explicit theology of a personal God. The Analects show that Confucius was largely silent on metaphysical issues; he transmitted earlier wisdom and moral maxims, often avoiding discussion of deitiesiep.utm.edu. In traditional East Asian thought, Confucius became highly venerated (temples and rituals to his honor are common), but he is not regarded as a divine messenger or lawgiver. Thus, from the perspective of Islamic theology (which hinges on tawḥīd and divine revelation), Confucius stands more as a revered thinker akin to a philosopher or saint, rather than a nabi with revealed scripture. Some modern Muslim-Confucian dialogues do highlight parallels (e.g. both stress filial piety and social ethics), but they generally stop short of labeling him a prophetiep.utm.eduplato.stanford.edu.

Conclusion

In conclusion, classical Islamic sources do not identify Buddha or Confucius as prophets, though they acknowledge the existence of their religions and sometimes compare aspects (e.g. Buddha–Khidr). Modern Muslim thinkers are divided: a minority deem Buddha an unnamed prophet (citing Qur’anic verses allegorically and hadith on universal prophethoodacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id), and the heterodox Ahmadiyya likewise regard Confucius as a prophetalislam.org. Most Sunni scholarship, however, treats them as great teachers or righteous figures at best, consistent with Islam’s teaching that “Allah did not send any prophet except in the language of his people”crcs.ugm.ac.id. The broader Islamic position is that Allah’s guidance is universal, even if not every prophet is named; this leaves open the possibility (without firm evidence) that men like Buddha or Confucius fulfilled that role for their peoples. Ultimately, Muslim emphasis remains on recognizing the one True God and His final revelation in Islam, while acknowledging that His mercy and wisdom have long worked through many unknown messengers among humanityacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id.

Sources: Classical histories and tafsīr (al-Ṭabarī, al-Maqdisī, al-Shahrastānī, etc.) as summarized in modern scholarshipacademia.educrcs.ugm.ac.id; contemporary Islamic scholars (Hamidullah, Hamid Qadir, Hamza Yusuf, Kazemi, Imtiyāz Yusuf, Rashīd Rida, etc.) hts.org.zahts.org.za; Qur’anic verses and hadith (with commentaries) crcs.ugm.ac.idacademia.edu; and comparative sources on Buddhist and Confucian traditions devdutt.complato.stanford.edu iep.utm.edu.

Leave a comment