Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract:

Relations between marginalized communities and majority groups can transform profoundly over time. The journey of Black and white Americans – from the horrors of slavery and the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to the gradual healing of wounds in the 21st century – exemplifies how dialogue and empathy can erode hatred. A striking example is Daryl Davis, a Black musician whose courageous conversations led over 200 KKK members to renounce their robes businessinsider.com. This article explores insights from Davis’s story and draws parallels to the struggles and aspirations of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, a persecuted minority among Muslims. Ahmadi Muslims’ interactions with other Muslims have often been marked by misunderstanding and hostility, yet the ethos of “Love for all, hatred for none” offers a path forward. By examining how racial divides have been bridged and how Ahmadi Muslims seek dialogue despite intolerance, we highlight a narrative of reflection, resilience, and hope. Through direct voices – from Davis’s own words to the Ahmadiyya Caliph’s guidance – this comprehensive discussion underscores the power of respectful engagement in healing old rifts.

From Slavery’s Shadows to Healing Wounds

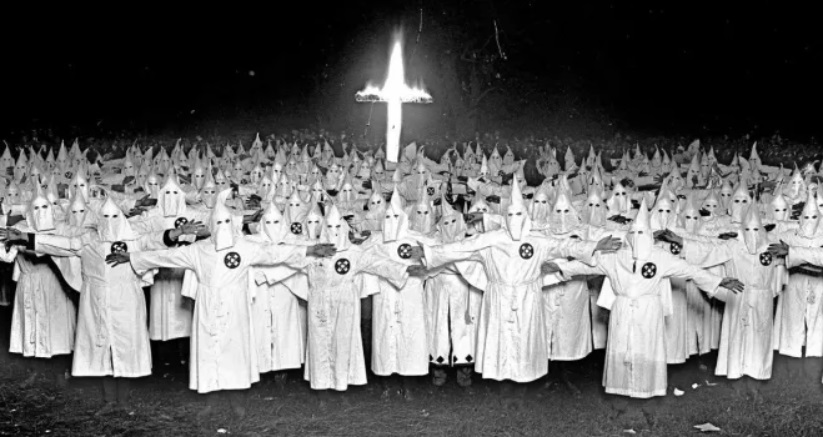

For centuries, Black and white relations in America were defined by oppression, violence, and enforced separation. The legacy of slavery and segregation fostered deep wounds and mutual distrust. The Ku Klux Klan, America’s oldest hate group, epitomized this era of racial terror. In the 1920s, KKK membership swelled into the millions, reflecting a widespread embrace of racist ideology en.wikipedia.org. Fast-forward to today, and that once-powerful movement has been reduced to a fringe: only an estimated 3,000 to 8,000 Klan members remain active in the U.S. en.wikipedia.org. Society’s overwhelming rejection of such hatred is evident in changing attitudes – for example, 94% of Americans now approve of Black–White marriages, up from a mere 4% in 1958 news.gallup.com. These numbers tell a story of remarkable progress: where racism was once enshrined in law and custom, now equality and integration are widely held ideals. The journey has been arduous and is not complete, but the trajectory is clear. The wounds of the past have slowly begun to heal, through civil rights struggles, changing laws, and evolving social norms.

One of the profound lessons from this transformation is the role of dialogue and personal connection in combating prejudice. Laws can change behavior, but hearts often change through humanizing encounters. Nowhere is this more poignantly illustrated than in the story of Daryl Davis, who took an unconventional path to erode prejudice.

Daryl Davis: Confronting Hate with Curiosity and Respect

Daryl Davis (left) with a Ku Klux Klan member during one of his conversations. Through patient dialogue, Davis “untangled a knot of hate that had coiled for decades,” often leading KKK members to question their beliefs theguardian.com.

Daryl Davis’s approach to bridging the Black–white divide was as radical as it was simple: he sat down with those who hated him. A chance encounter in 1983 set the stage – performing music at a bar in Maryland, Davis was approached by a white patron who praised his piano skills but admitted it was the first time he’d ever had a drink with a Black man theguardian.com. When the man revealed he was a KKK member, Davis did not react with anger. Instead, he grew curious. “I was instantly curious and thought, ‘What’s going on here?’ So I asked him why [he had never met a Black person before],” Davis recalls theguardian.com. This friendly yet frank conversation blossomed into an unexpected friendship. It also ignited Davis’s quest to answer the question that had haunted him since age 10 when he first encountered racism: “How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?” businessinsider.com.

Over the next few decades, Davis actively sought out Klan members for honest conversations. He attended KKK rallies, visited the homes of Klansmen, and even invited them into his own home – all in an effort to understand the roots of their hatred. Davis approached these dialogues armed not with indignation, but with diplomacy and respect. As he explains, “I used diplomacy in these conversations… I’ve learned that every human being wants to be loved, respected, heard, treated fairly and truthfully, and wants the same things for their family. If we can learn to apply those five core values, we can navigate even adversarial situations much more smoothly and positively.” businessinsider.com. This meant listening calmly even when hearing outrageous racist claims. “When I say respect, I don’t mean I necessarily respected what they said, but rather their right to say it,” Davis notes businessinsider.com. By staying composed instead of lashing out, he found that his calm defused their anger. Klansmen who expected a fight instead found themselves in a conversation – and “now their ears are open” to receive new ideas businessinsider.com.

The results were astonishing. One by one, some of the most diehard racists began to soften. In many cases, civil dialogues led them to quit the Klan, no longer able to reconcile their prejudice with the human being they had come to know theguardian.com. Over time, more than 200 KKK members chose to leave the organization, turning in their robes to Davis as tokens of their personal transformation businessinsider.com. “I did not convert anybody. Over 200 Klan members have converted themselves,” Davis emphasizes. “I go to them to find out why they believe what they believe. The more we conversed, the more people would change.” businessinsider.com His role was not to argue or plead, but to plant seeds of doubt and provide the impetus for change theguardian.com. Davis’s living room today is a striking museum of reconciliation, adorned with Klan robes and hoods given to him by former members who no longer needed them businessinsider.com. Each robe, Davis says, represents “not a trophy, but a soul changed” – a testament to the power of reaching across divides.

Daryl Davis’s story provides a blueprint for healing hatred: approach even your adversary with genuine curiosity, affirm their humanity even when you reject their ideas, and create a space where understanding can grow. “Of course, some people go to their graves with hatred in their hearts,” he acknowledges. “But what gives me hope… is the fact that I’ve seen it work. I’ve seen people change.” businessinsider.com Davis’s success is a microcosm of broader racial progress – it demonstrates how far empathy and engagement can take us. If such transformations are possible in the context of entrenched racism, could similar bridges be built in other divides, such as within the Muslim world? The experience of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which has long faced hostility from other Muslim sects, raises this question poignantly.

Ahmadiyya Muslim Community: Between Persecution and Dialogue

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community (whose members are often called Ahmadi Muslims or Ahmadis) is a religious movement founded in 1889 in British India. Ahmadis identify as Muslims in every respect – they follow the Quran, revere Prophet Muhammad, and observe Islamic practicesen.wikipedia.org. However, a core theological difference has set them apart: Ahmadis believe that their founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, was the Promised Messiah and Mahdi, a divinely guided reformer. Mainstream Islamic doctrine holds that Muhammad is the final prophet, so many Sunni and Shia Muslims regard Ahmadis as heretics for revering a later figureen.wikipedia.org. This dispute over prophetic succession has had stark real-world consequences. In several Muslim-majority countries, Ahmadis have been officially branded non-Muslims and subjected to systematic discriminationen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

Nowhere has this been more pronounced than in Pakistan, which hosts the largest Ahmadi population. Pakistan’s constitution was amended in 1974 to explicitly define Ahmadis as non-Muslims, and a series of laws (notably Ordinance XX of 1984) criminalize Ahmadis for using Islamic greetings, calling their worship places “mosques,” or publicly quoting the Quranen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Essentially, Ahmadis are forbidden by law from “posing” as Muslims in Pakistanen.wikipedia.org. The social climate is equally hostile – school textbooks and clerics often spread vitriol against the communityen.wikipedia.org. Violence has erupted on many occasions: anti-Ahmadi pogroms and terror attacks have claimed hundreds of lives, such as the deadly Lahore mosque attacks of 2010 that killed 84 Ahmadi worshippersen.wikipedia.org.

In the broader Muslim world, intolerance toward Ahmadis remains common. A Pew Research poll in late 2011 found that two-thirds of Pakistani Muslims refused to accept Ahmadis as fellow Muslims, with only 7% willing to recognize them as such pewresearch.org. Draconian blasphemy and anti-Ahmadi laws enjoy broad popular support – 75% of Pakistani Muslims say blasphemy laws (frequently used against Ahmadis) are necessary to protect Islam, and only a tiny minority believe these laws unfairly target religious minorities pewresearch.org. Even in countries without official anti-Ahmadi laws, the community often faces social ostracism, harassment, or exclusion from the Muslim mainstream. In essence, the relationship between Ahmadis and other Muslims has long been characterized by fear and prejudice, not unlike the dynamic between segregated whites and Blacks in America’s past. Ahmadis are frequently viewed as traitors to Islam or as a deviant sect to be shunned – a painful reality for a community that views itself as genuinely Muslim and devoted to the faith’s revival.

Yet, amidst this bleak landscape, there are glimmers of hope and efforts at dialogue. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s ethos has always emphasized peace and outreach, encapsulated in their slogan “Love for All, Hatred for None.” Despite being persecuted, Ahmadis are taught to respond with patience and prayer rather than retaliation. In a recent address, the community’s spiritual leader (Khalifa), Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, spoke directly about how Ahmadis regard other Muslims: “As far as our relationship with [other] Muslims and our sympathy for them is concerned, we adhere to the teaching of the Promised Messiah… ‘O heart, treat these people with kindness, For they ultimately claim love for the Prophet.’ We, therefore, maintain love for every Muslim, pray for their well-being, and make every effort within our capacity for their benefit. We hold sincere feelings for them and pray for their guidance.”pressahmadiyya.com. These words – “we maintain love for every Muslim” – are remarkable, given that many of those same Muslims do not reciprocate that sentiment. The Ahmadiyya leader implored mainstream Muslims to reconsider their hostility: instead of reflexively declaring Ahmadis as non-believers, “they should listen to and try to understand [our] message. They should not hastily issue fatwas of disbelief.”pressahmadiyya.com In other words, he appealed for open ears and hearts – much as Daryl Davis did with his adversaries.

Instances of intra-Muslim engagement have begun to emerge, especially in the West where freedom of religion allows more openness. In the United States, for example, an extraordinary event took place in 2013 in Houston: a formal intrafaith dialogue panel featuring Sunni, Shia, and Ahmadi Muslim imams sharing the stagesjpaderborn.wordpress.com. It was described as a rare, perhaps first-of-its-kind, occasion for such direct conversation. The imams discussed what beliefs define a Muslim, how to accept differences, and the need for reform to build cohesive societiessjpaderborn.wordpress.com. This event demonstrated that respectful discourse is possible – that even those who disagree on theology can sit together to talk “within and without” the community about unity and pluralismsjpaderborn.wordpress.com. The very existence of this dialogue signaled a willingness (at least among more open-minded leaders) to “build bridges” and model the Quranic ideals of brotherhood.

Beyond formal events, ordinary individuals have also taken steps of empathy. When hateful violence strikes, it sometimes paradoxically brings communities closer. A moving example occurred in Glasgow, Scotland in 2016: an Ahmadi shopkeeper named Asad Shah was brutally murdered by another Muslim because of his Ahmadi faiththeguardian.comtheguardian.com. The atrocity shocked the local community. In response, hundreds of people of all faiths and backgrounds held vigils for Mr. Shah, honoring the gentle man who had preached love and peace to all. Locals – including many non-Ahmadi Muslims – laid flowers and shared grief together for several nightstheguardian.comtheguardian.com. “The community has reacted – he has brought everybody together,” said one organizer, a Muslim teenager from the neighborhood. “Hopefully this is a lesson that we need to stick together.”theguardian.com In that somber gathering, labels seemed to melt away; what mattered was the shared human loss and a collective stand against hate. While it’s tragic that it often takes a tragedy to spark unity, such moments reveal an undercurrent of conscience: a recognition that, despite theological rifts, Ahmadis are humans and neighbors deserving compassion. They show that the healing of intrafaith wounds is possible, even if only in fragile, fleeting bursts of solidarity.

Love, Dialogue, and the Road Ahead

The parallels between the racial reconciliation journey and the struggle for acceptance within the Muslim Ummah are striking. In both cases, longstanding prejudice has dehumanized a group – Black people in one, Ahmadi Muslims in the other – and in both, change begins when individuals challenge their own prejudices through personal encounter. A century ago, many white Americans had never socially interacted with Black individuals except in roles of servitude; ignorance fueled fear. Similarly, today many Muslims who despise Ahmadis have never actually met one in a context of friendship or open dialogue – they “know” them only through demonizing propaganda. The result is a host of misconceptions (for example, the false claim that Ahmadis disrespect Prophet Muhammad, when in fact they profess profound love for himpressahmadiyya.com). Breaking these misconceptions requires the same bravery that Daryl Davis showed: the courage to sit with the so-called enemy and simply talk.

As the humanitarian Elizabeth Arif-Fear notes, sectarian conflict in Islam – whether Sunni–Shia tensions or persecution of Ahmadis – has persisted for ages, and it often seems intractablevoiceofsalam.com. How do we move forward? she asks. How can we bring people together across such divides? The answer, she concludes, is “dialogue”voiceofsalam.com. Dialogue does not mean erasing differences, but it does mean humanizing those differences. It means, as Cambridge interfaith researchers put it, learning “how to begin the conversation” even when it’s uncomfortablevoiceofsalam.com. Importantly, dialogue must be two-sided. The onus cannot be only on Ahmadis to reach out to those who shun them; mainstream Muslim scholars and communities must also be willing to engage. That requires moral leadership – voices willing to say, “We may disagree theologically, but we will still shake your hand and hear your story.” Such voices remain relatively few, but they are growing as global Muslim discourse slowly grapples with principles of pluralism and freedom of belief.

For Ahmadi Muslims, there is a bittersweet hope in watching how dramatically other entrenched hatreds have diminished over time. Within living memory, in the United States, a Black person risked his life to simply drink from the wrong water fountain, and a white person risked ostracism to marry someone Black. Now a Black man and a white woman can marry and hardly anyone bats an eye; indeed, an overwhelming majority of Americans see nothing wrong with itnews.gallup.com. The idea of a Black U.S. president was once unthinkable; now it is history. Bigotries can fade – not by forgetting the past, but by overcoming it with new understanding. The healing of racial wounds is still ongoing, but each generation has grown more tolerant than the last. Many Black and white youths today interact with an ease that would astonish their grandparents. In the same way, we can imagine a future where Sunni, Shia, and Ahmadi Muslims regard each other not with suspicion but with siblinghood under the banner of Islam, even while maintaining their distinct beliefs. It will require time, purposeful education, and above all courageous interpersonal engagements.

Every conversation that bridges a divide is a small miracle. Just as Daryl Davis kept his cool in the face of hate, Ahmadi Muslims have shown extraordinary restraint and perseverance. They continue inviting others to visit their mosques, attend interfaith dinners, and ask questions. Many non-Ahmadi Muslims who have dared to attend an Ahmadi gathering (often out of curiosity) come away surprised to find fellow Muslims praying and preaching peace, not the caricature of a cult they were told to expect. These moments can plant the seed of doubt – perhaps the Ahmadis aren’t so bad, perhaps they are Muslims after all. Change often begins with such humble realizations.

Epilogue: Towards a Harmonious Ummah

In a quiet room in Silver Spring, Maryland, a Black man gently fingers the robes of former Klansmen, each garment a silent witness to hatred dissolved. In another part of the world, an Ahmadi Muslim bows his head in prayer, whispering for those who denounce him to one day see the truth of his love. These two scenes – outwardly unrelated – are connected by a profound common thread: the belief that hearts can change. The journey from hate to understanding is the quintessential human saga, whether it unfolds between races, religions, or sects.

The story of Black–white reconciliation offers a powerful message of hope to Ahmadi Muslims and their detractors alike: today’s seemingly unbridgeable chasms can become tomorrow’s footnotes in history books. Who could have predicted that a Black man’s dialogue would lead KKK members to renounce racism? Yet it happened, one conversation at a time. Likewise, it may seem fanciful now that Sunni or Shia leaders would ever welcome Ahmadis as fellow Muslims – but with patience and persistence, hearts can soften. Prejudices, no matter how hardened, are ultimately products of ignorance and fear, and thus not impervious to change.

The road ahead for the Muslim Ummah is challenging. It demands the courage to question inherited biases and the empathy to see the divine spark in the “other.” It calls for more Daryl Davises within Muslim communities – individuals willing to engage ideological opponents with a smile and a Qur’an in hand, rather than a clenched fist. It calls for humility on all sides: the humility to admit that only God can judge the faith in our hearts, and that our duty is to “learn to know one another” as the Quran (49:13) enjoins. Most of all, it calls for love – that radical, active love which the Ahmadiyya motto preaches and which can disarm even the fiercest foe.

Every time an Ahmadi prays for a Muslim who has cursed him, every time a mainstream Muslim stands up for an Ahmadi’s right to worship, a small crack appears in the wall of division. Over years and decades, those cracks can widen, letting in light. The healing of sectarian wounds, like the healing of racial wounds, is a gradual, generation-spanning process. There will be setbacks and sorrows, as there have been in race relations, but the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice, as Martin Luther King Jr. said. In the end, truth and love prevail over falsehood and hatred – this is a promise ingrained in the ethos of all great faiths, including Islam.

As the evening sun sets on a world still rife with conflicts, one cannot help but imagine a future gathering – perhaps many years from now – where Sunni, Shia, and Ahmadi Muslims pray side by side, their children scarcely remembering why their ancestors ever fought. In that future, an Ahmadi child might ask, “Were we really hated once upon a time?” – and her Sunni friend might shake his head in wonder. That future begins now, in the quiet, brave interactions of people who choose dialogue over discord. The journey from estrangement to brotherhood is long, but every step – every handshake, every shared meal, every earnest debate – carries us closer to a day when the Muslim Ummah can truly embody the Prophet’s teaching that “the believers are but brothers.”

In the words of a young Glaswegian who saw her community unite after tragedy, “Hopefully this is a lesson that we need to stick together.”theguardian.com The lesson is heard, and with the grace of God, it will echo. From the ashes of hate, understanding can rise – and with it, the dawn of a more harmonious world for us all.

Leave a comment