Presented by Zia H Shah MD

The Chain of Determinism from the Big Bang

Modern secular thought often envisions the universe as a closed causal chain stretching back to the Big Bang. In this view, every event is the effect of prior events, forming an unbroken stream of cause and effect. Pierre-Simon Laplace famously illustrated this deterministic worldview with his thought experiment of a vast intellect (later dubbed Laplace’s Demon) that, knowing all forces and positions of particles at one moment, could compute all future and past states of the universeen.wikipedia.org. As Laplace wrote, “We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future”en.wikipedia.org. This captures the clockwork universe idea: given the initial conditions of the cosmos and the laws of nature, everything that happens – from galaxies forming to our very thoughts – is determined in principle. Classical Newtonian physics embodied this strict causality and predictability, reinforcing the notion that the cosmos runs like a machine following inviolable laws. Many scientists and atheist philosophers embraced this, arguing that no external agency is needed once the initial setup is in place. The astrophysicist Carl Sagan, for example, opened his Cosmos series with the credo: “The Cosmos is all that is, or ever was, or ever will be,” underscoring a self-contained reality requiring no outside cause.

Atheist thinkers have often taken this deterministic cosmology to imply that God is unnecessary. If the chain of causation explains everything, what role remains for a creator? When Napoleon queried Laplace on why his great astronomy treatise made no mention of God, Laplace coolly replied, “I had no need of that hypothesis.”en.wikipedia.org. In other words, the laws of physics alone sufficed to explain the solar system’s mechanics, with no divine intervention required. Philosophers like Bertrand Russell likewise argued that the universe’s existence is a “brute fact” needing no further explanation. In a 1948 debate, Russell bluntly stated, “I should say that the universe is just there, and that’s all.”thequran.love. By this view, it is meaningless to ask why there is a universe or what caused it – the cosmos may be an eternal, self-existent reality or simply an unexplained given. Such perspectives reflect a metaphysical naturalism: reality is a closed loop of natural causes, from the big bang to now, and any appearance of design or purpose is emergent from mindless physical processes.

It is important to note that 20th-century science complicated this tidy determinism. In particular, quantum mechanics shattered the strict predictability of Laplace’s clockwork universe. At microscopic scales, events can be truly random or indeterminate: for example, we cannot predict exactly when a given atom will decay radioactively – only the probability of decaythequran.love. As one physicist put it, firing photons at a half-silvered mirror yields an exact 95% transmission rate in aggregate, yet no one can predict which individual photons will pass through or reflect; “there is no deterministic cause deciding each photon’s fate”thequran.love. Such quantum indeterminacy shows that even with fixed initial conditions, nature allows multiple possible outcomes. Classical determinism thus has “looseness at the joints”thequran.love. Nonetheless, many atheists hold that even if physics is not strictly deterministic, it remains causally closed – quantum events are “random” rather than guided, and there is still no room (or need) for divine agency. In effect, whether the universe unfolds like clockwork or with some probabilistic wiggle, the assumption is that natural laws and initial conditions are sufficient to account for everything. The role of a Creator is either entirely dismissed or pushed back to the very first instant, after which the universe runs on autopilot. In popular science writing, one even encounters attempts to explain the origin of the universe itself in purely physical terms – for example, physicist Stephen Hawking’s proposal that a quantum cosmology could allow the universe to “create itself from nothing” under the law of gravitythequran.love. Upon scrutiny, however, such claims reveal that something (like the law of gravity or a quantum vacuum) is still assumedthequran.love. As critics pointed out, Hawking’s “nothing” was not truly nothing – it presupposed a framework of physical laws, leading one of his colleagues, George Ellis, to ask pointedly: “Who or what ‘dreamt up’ the laws of physics?”thequran.love. In essence, even the most reductionist accounts end up with unexplained laws or brute facts. Thus, while the atheist-materialist perspective often treats the causal chain as ultimate, it faces the profound question: Why does this chain exist at all? If every event has a prior cause, what was the First cause?

The First Cause in Abrahamic Thought: A Transcendent Creator

Where materialist philosophy sees an endless (or self-contained) causal stream, the Abrahamic faiths posit a definite beginning – a First Cause that is uncaused. In monotheistic tradition, the universe is not “just there” eternally; rather, it was brought into existence by the deliberate will of God. “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth,” opens the Book of Genesis, asserting that time and space have a starting point in divine creation. The Qur’an likewise proclaims God as “the Originator of the heavens and the earth” (Arabic: badi’u s-samawati wal-ard) who simply says “Be!” and the universe isthequran.lovethequran.love. This concept of creation ex nihilo (creation out of nothing) was radical in antiquity. Greek philosophers such as Aristotle had reasoned that ex nihilo nihil fit – from nothing, nothing comes – and thus assumed the cosmos (or at least prime matter) must be eternalthequran.love. The Abrahamic response turned this on its head: yes, from nothing, nothing comes – unless there is an omnipotent Creator who can call reality into being. If the universe had a beginning, it points to something (or Someone) beyond the universe as its cause. As the Qur’an pointedly asks those who deny God: “Were they created from nothing, or were they the creators [of themselves]?”thequran.love. This logical disjunction – either the universe popped into existence uncaused, or it has a transcendent cause – lies at the heart of the cosmological argument in theologythequran.love.

Remarkably, modern cosmology has lent weight to the scriptural notion of a beginning. The Big Bang theory, now the dominant scientific model, says the universe expanded from a singular origin about 13.8 billion years ago, before which our familiar spacetime did not exist. This discovery overturned the old Aristotelian notion of an eternal universe – a notion that medieval theologians like Al-Ghazālī had vehemently argued againstthequran.love. Al-Ghazali’s philosophical opponents (e.g. Avicenna) held the cosmos was eternal and ran on its own principles; Ghazali, drawing on the Qur’an, insisted the world was created in time by God’s decreethequran.love. For centuries, the eternity of the world was a sticking point in debates between philosophers and theologians. Yet today, science affirms a cosmic beginning ab initio. As a 20th-century astronomer wryly noted, many scientists initially resisted the Big Bang theory “partly because it seemed to lend support to the Genesis creation narrative”thequran.love – Fred Hoyle, an atheist, even coined the term “Big Bang” sarcastically. But evidence kept building, and now the idea of a beginning is inescapable. Time and space had a starting point, and physics as we know it breaks down approaching that initial singularitythequran.love. This vindicates what Al-Ghazali and others deduced on philosophical grounds: the universe appears “radically contingent, having come into being from nothing physical”thequran.love. Science, of course, can describe the expansion after the first moment, but it cannot say why there was a first moment at all. As one commentary puts it, physics can trace events back to a “t = 0” boundary, but “it does not tell us what (if anything) ‘came before’ that, or what caused it.”thequran.lovethequran.love. For believers, this is precisely where God enters the picture – not as a gap-filler for what we don’t yet know, but as the logical explanation for why there is a universe with laws in the first place.

Crucially, the role of God in Abrahamic thought is not confined to a one-time push at the beginning. God is not a mere cosmic spark that ignited the Big Bang and then went hands-off. Rather, God is continuously sustaining reality at every moment. In Christian theology, one finds the idea that “in Him all things hold together,” and in the Islamic tradition this concept is even more explicitly emphasized. The Qur’an repeatedly describes Allah not as an absentee clockmaker but as the immanent sustainer of the universe. “Indeed, God holds the heavens and the earth, lest they cease [to exist]. And if they should fail, no one could hold them [up] after Him,” says one versethequran.love. Another verse, addressing the Prophet Muhammad’s seemingly mundane act in battle, declares: “You did not throw when you threw, but God threw.” In other words, even an action performed by a human hand was, in reality, caused by Godthequran.love. Such verses drive home three core theological principles in Islam: (1) No independent causality in creation – “The outcome of every affair is with God” (Qur’an 31:22); (2) Continuous divine action – “Every day He is engaged in an affair” (Qur’an 55:29), meaning creation is ongoing at each instant; and (3) Absolute sovereignty – nothing in heaven or earth lies outside His will and knowledgethequran.love. In short, not only does God initiate the cosmos, He pervades every moment of its existence. The very fabric of reality, in this view, is being held up by the command of a transcendent yet intimately involved Deity. The 13th-century Christian philosopher Thomas Aquinas expressed a similar idea by saying that if God’s support were withdrawn, the universe would lapse back into nothingness in an instant. Likewise, Islamic theology speaks of “Allah’s kursī (Throne) extending over the heavens and earth, and their preservation tiring Him not” (Qur’an 2:255) – indicating that the world persists only through God’s effortless upkeepthequran.love. This continuous-creatorship concept means that every natural law and causal relationship is, at root, a manifestation of God’s will. The laws are His customs in managing the universe, not independent machinery. With this theological backdrop, we move from the idea of a First Cause to a yet more robust doctrine: occasionalism, which argues that God’s causality is not only first in time but exclusive at all times.

From First Cause to Every Cause: Al-Ghazali’s Occasionalism

If we combine the premise of a deterministic causal order with the premise of an omnipotent God as the originator and sustainer of that order, we arrive at occasionalism – the doctrine that God is the only real cause and what we call “causes” in nature are merely occasions for divine actionthequran.love. Al-Ghazālī (1058–1111), one of Islam’s greatest theologians, famously championed this view. He lived at a time when philosophers influenced by Aristotle and Neoplatonism argued that things in the world had inherent causal powers – fire by its nature burns cotton, bread by its nature nourishes, and so on. In his landmark work Tahāfut al-Falāsifa (“The Incoherence of the Philosophers”), Ghazali mounted a vigorous critique of this notion of necessary causality in naturethequran.love. His bold thesis was that all causal power ultimately resides with God alonethequran.love. For any event that occurs – a leaf falling, a person lifting an arm, a planet orbiting the sun – the true immediate cause is God’s will at that moment, not some autonomous force or law within the creation. The so-called laws of nature are merely the habitual patterns by which God ordinarily wills the world to runthequran.love. But God can suspend or alter these patterns at any time, which is exactly what miracles are: exceptions to the usual order, enacted by the Supreme Cause.

Al-Ghazali’s reasoning hinged on safeguarding the absolute omnipotence and omniscience of God. If something in creation had independent causal efficacy – say, if fire could burn on its own – then that would place a limit (however small) on God’s total controlthequran.love. In Ghazali’s analysis, this is inadmissible: “If something had its own causal power, how would that square with God’s all-encompassing knowledge and control?”thequran.love. A truly all-powerful, all-knowing deity cannot be excluded from any event in the universe, no matter how mundane. Therefore, Ghazali insists that every link in the causal chain is forged anew by God at each instantthequran.love. The fire and cotton do not have built-in power to produce burning; rather, when the cotton meets the flame, it is God who creates the burning as that encounter’s outcomethequran.love. If at some point He wills otherwise, the cotton would not burn – as, indeed, the Qur’an recounts that Abraham was thrown into a fire and “it did not burn him” by God’s command (Qur’an 21:69)thequran.love. By the same token, a knife does not cut by itself – when Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son, the knife was divinely prevented from cutting. These scriptural examples illustrate the occasionalist principle that nothing has an intrinsic, guaranteed effect; outcomes only follow because God usually wills a consistent patternthequran.love. In everyday life, it appears that causes produce effects – fire burns, bread nourishes, medicine heals – but Ghazali would say this is like a habit or custom of God (sunnat Allāh), not an iron necessity. At any moment, God could decree a different result. Thus, causation as we observe it is contingent on God’s ongoing decision to allow those patterns.

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism was essentially a theological solution to a philosophical puzzle: how to reconcile the evident order of secondary causes with an absolutely sovereign God. His solution was to collapse secondary causes entirely into God’s direct agency. To borrow Ghazali’s own metaphor, the universe is like a grand theater where God is the only actor – what we call “natural causes” are merely props or occasions for the Actor to do various deedsthequran.love. This doctrine had the added apologetic benefit of upholding the possibility of miracles: since nature has no fixed causal power of its own, nothing prevents the Author of nature from doing something out of the ordinary. There are no true “laws of nature” that bind God’s handsthequran.love. Fire will usually burn cotton because God’s wisdom usually maintains a stable order (making science and daily life possible), but He can make fire not burn if He so wills – without violating anything, since the only laws are His choicesthequran.love. In Ghazali’s view, this preserves tawḥīd (the oneness of God) in the realm of causation: attributing real power to creatures or natural forces would be a subtle “shirk” (association of partners with God) in powerthequran.lovethequran.love. To truly affirm La ilaha illallah (“there is no god but God”), one must recognize that there is no real cause but God. As later Ash‘ari scholars phrased it, “La fa‘ila illallah” – no doer except Godthequran.love.

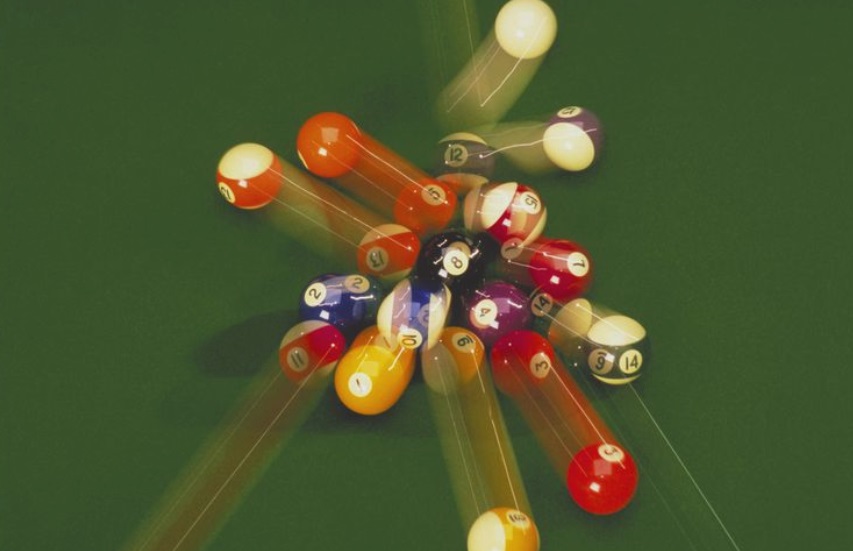

It is worth noting that occasionalism, though often caricatured as a medieval oddity, finds resonance in modern philosophical and scientific insights. David Hume, the 18th-century skeptic, argued that we never actually observe a necessary connection between cause and effect – only that one event regularly follows anotherthequran.love. We see the billiard ball A strike ball B and then B moves, but we do not see any mystical “power” passing from A to B; the constant conjunction is all we know. Hume concluded that our belief in causation is a habit of the mind, not a logically provable truththequran.love. This remarkably echoes Al-Ghazali (albeit with God left out): Ghazali had said centuries earlier that what we call necessity is just the habitual sequence Allah has put in place, and we have no guarantee it couldn’t be otherwisethequran.love. In essence, Hume secularized Ghazali’s occasionalist critique of causality – both denied that intrinsic necessary causation is empirically or rationally demonstrable. More recently, quantum physics has further eroded the old notion of deterministic necessity. As discussed, at the fundamental level, events unfold in probabilistic ways, and outcomes aren’t strictly forced by prior statesthequran.lovethequran.love. Physicists admit a degree of irreducible uncertainty in nature. Some scholars have noted that this “reopened a conceptual space” for divine agencythequran.love. Because physics only gives probabilities, one can philosophically imagine God “selecting” each outcome within the allowed rangethequran.love. To science, these choices would appear random, but an occasionalist could interpret them as the subtle, untraceable hand of God working within natural lawsthequran.lovethequran.love. In fact, theologians like John Polkinghorne have proposed that God might influence indeterminate quantum events as a way of guiding nature without overriding natural laws – an idea compatible with occasionalism (which would take it a step further and say God determines all events, not just quantum ones)thequran.love. Even the bizarre phenomenon of quantum entanglement – where two particles behave in coordinated ways with no causal contact – has an occasionalist flavor. After all, entanglement shows that spatially separated events can be correlated beyond any local physical mechanismthequran.lovethequran.love. It is as if, when one particle is measured, the other “just happens” to line up accordingly with no signal passing between themthequran.love. Some physicists invoke a single, underlying reality tying them together. An occasionalist would comfortably say: indeed, the underlying unity is the one will of the one Creator, who coordinates all eventsthequran.love. Notably, when the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics confirmed that nature violates “local realism” (no hidden local causes for entangled correlations), it underscored that the universe cannot be fully described by local material causes alonethequran.love. One can’t help but hear echoes of Ghazali’s insistence that “creatures have no fixed powers or natures independent of God’s continual bestowal”thequran.love.

Far from rendering science useless, Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism embraces science as the study of God’s habits. The Ash‘ari theologians taught that secondary causes are still meaningful on the level of observation – fire does burn wood consistently, so we can study how and under what conditions this occursthequran.love. Ghazali himself was a polymath who studied medicine and astronomythequran.love, illustrating that one can investigate nature rigorously while believing that nature’s regularity is sustained by Godthequran.love. Occasionalism only denies that these regularities are self-sufficient or inviolable. It says, in effect, that science describes the how, but theology describes the ultimate whythequran.lovethequran.love. The laws of physics are accurate models of how phenomena relate – but they are not the deepest explanation for why those relations holdthequran.love. That deeper explanation is the constant creative will of God. As one scholar elegantly put it, natural laws are the “customs of the King”, and just as a king can suspend his realm’s usual order if he pleases, God can depart from the ordinary course of nature whenever He willsthequran.lovethequran.love. In everyday life, we operate as if causes have their own efficacy – and for practical purposes, this assumption works. But on reflection, the believer realizes that at each moment, the cosmos is like a cosmic simulation being rendered by a divine mindthequran.lovethequran.love. Some contemporary thinkers even liken our reality to a computer simulation, with God as the programmerthequran.lovethequran.love. In that metaphor, what we call “natural causation” is just the code that God normally runs – it has no power of its own, and the Programmer can tweak or override it at willthequran.lovethequran.love. This is a modern analogy to occasionalism that resonates with tech-minded people: just as a video game character can only act because the computer’s processor is continuously executing the code, creation only “acts” because God’s command “Be!” is continuously sustaining itthequran.love.

A Synthesis of Determinism and Theism

Bringing the threads together, we see a grand synthesis emerging: a universe that is orderly and law-bound (as science shows), yet utterly dependent on a transcendent God at every moment (as religion teaches). In this view, determinism and divine will are not rival explanations but complementary. The deterministic “stream” since the Big Bang is real, but it is real because God is its source at every point. Every event is both fully caused by prior events and fully caused by God. To the believer, these are different levels of description – one horizontal, within creation; the other vertical, from Creator to creationthequran.love. Occasionalism crystallizes this by asserting that the entire causal network of the cosmos is like a tapestry woven in real-time by God. The Big Bang was the first thread He laid down – “He is the First and the Last” (Qur’an 57:3) – and every subsequent thread in the fabric of reality is His weaving toothequran.love. Thus the scientific fact that the universe has a history stretching back 13.8 billion years, with each moment arising from the previous, is perfectly compatible with the theological fact that “Every day He is engaged in an affair” (Qur’an 55:29) of sustaining creationthequran.love. In the occasionalist understanding, if we ask “What caused this event?” there are always two valid answers: one is the physical cause (e.g. the proximate prior conditions) and the other is “God’s will.” These do not conflict because they operate at different explanatory levels. As the Qur’an says of a battle incident: “It was not you who threw when you threw, but God threw”thequran.love – the action can be attributed to the human actor on one level, but to God as the ultimate cause on another. Islamic theology developed the doctrine of kasb (“acquisition”) to harmonize divine determinism with human responsibility: God creates the act, but humans acquire it by their intention, hence are accountablethequran.love. In a sense, our free choices are the occasions for God to create corresponding outcomes, which preserves moral agency within an overall occasionalist framework.

In conclusion, Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is the logical culmination of joining a rigorous determinism with a robust theism. It says that the causal order from the Big Bang onward is real and evident – but it is a dependent reality, a shadow play of the one omnipotent Actor behind the scenes. This worldview has a profound spiritual implication: it fills the universe with the presence of God. Nothing is “just there, and that’s all.” Everything, from the firing of neurons in our brains to the fusion of stars in distant galaxies, is a sign (āyah) pointing to the ongoing command of Godthequran.love. The universe is not a cold, closed system grinding along on mathematical laws for no reason; it is a contingent, finely ordered reality that flows at each instant from an Intelligent and Purposeful Sourcethequran.lovethequran.love. This vision satisfies both the mind and the heart: the mind, because it recognizes in God the sufficient reason the causal chain demands, and the heart, because it finds the world imbued with meaning and divine presence rather than emptiness. As one contemporary commentator observed, science and faith “can converge on a sense of wonder about a reality that is at once lawful and profoundly dependent on something deeper.”thequran.lovethequran.love In that convergence stands Al-Ghazali, smiling across the centuries – vindicated both by modern physics’ hints of a beyond, and by timeless scripture – as he reminds us that every molecule and moment whispers, “Insha’Allah”, if God so willsthequran.love.

Sources:

- Shah, Z. H. (2025). Al-Ghazali’s Occasionalism and the Modern Understanding of the Universe. The Glorious Quran & Sciencethequran.lovethequran.lovethequran.lovethequran.love.

- Shah, Z. H. (2025). Occasionalism in Al-Ghazali’s Thought and the Quranic Emphasis on Divine Causality. The Glorious Quran & Sciencethequran.lovethequran.lovethequran.love.

- Shah, Z. H. (2025). Proving God as the First Cause: Creation Ex Nihilo and the Origin of Everything. The Glorious Quran & Sciencethequran.lovethequran.lovethequran.love.

- Shah, Z. H. (2025). Occasionalism and Divine Agency in Qur’an 35:9–14: A Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Commentary. The Glorious Quran & Sciencethequran.lovethequran.lovethequran.love.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2020). Occasionalism (entry on the doctrine’s history and arguments).thequran.lovethequran.love

- Laplace, P. S. (1814). A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. (Laplace’s articulation of causal determinism)en.wikipedia.org.

- Russell, B. & Copleston, F. (1948). BBC Radio Debate on the Existence of God. (Russell’s “universe is just there” argument)thequran.love.

- Hawking, S. (2010). The Grand Design. (Hawking’s claim about a self-creating universe and its critique)thequran.lovethequran.love.

- Holy Qur’an – verses as cited (31:22, 55:29, 8:17, 2:255, 21:30, 57:3, etc.)thequran.lovethequran.love.

Leave a comment