Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD

Ghamidi’s Quran-Centric Vision and Inclusive Outlook

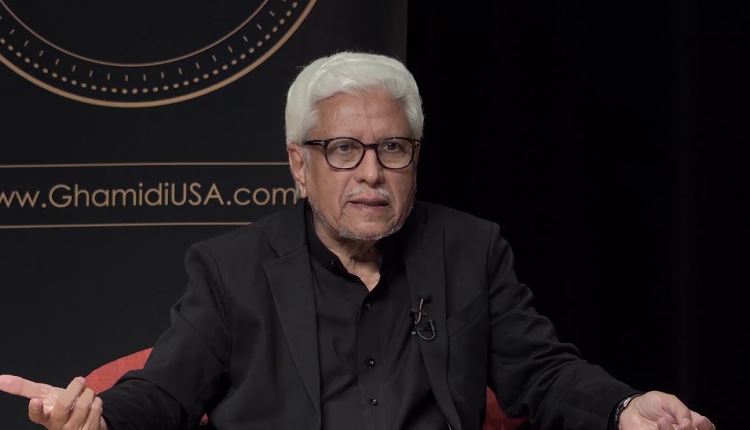

Javed Ahmad Ghamidi is a prominent contemporary Islamic scholar known for insisting that Islam’s authentic teachings reside in the Qur’an and Sunnah, while also engaging respectfully with centuries of scholarship. In a recent discussion filmot.comfilmot.com, Ghamidi recounts how he shifted from a Sufi-influenced upbringing to a Qur’an-centric approach. He grew up immersed in Sufi tradition – in youth he avidly read works like Tazkiratul Awliya by Sheikh Fariduddin Attar, finding in those saintly legends a source of joy, contemplation, and “mental maturation”filmot.com. His first exposure to faith was through a revered Barelvi scholar, Maulana Abu Tahir Muhammad Naqshband, under whom he offered his earliest Friday prayersfilmot.com. Ghamidi thus does not dismiss Sufi heritage out of hand; he warmly acknowledges the sincerity and devotion of these early influences. This inclusive outlook extends beyond Muslim sages – Ghamidi even references Western philosophers like Aristotle and Plato as examples of developing rich metaphysical worldviewsfilmot.com. He respects such philosophical endeavors, yet he draws a clear line: if one is presenting a deen (religious doctrine), the Qur’an’s authority must remain supremefilmot.com. In other words, human philosophies (whether Eastern or Western) are valuable intellectual pursuits, but they cannot override the revealed guidance of the Qur’an in defining Islamic belief and practice.

Notably, Ghamidi’s inclusive mindset is also evident in his pluralism within Islam. He maintains that anyone who calls themselves Muslim is to be treated as such, shunning sectarian exclusivism thequran.love. For instance, he has publicly acknowledged the Muslim identity of the oft-persecuted Ahmadiyya community (declared non-Muslim by Pakistani law), a stance that reflects his broad-minded acceptance of diverse interpretations within the faith thequran.love. This breadth of vision – valuing the contributions of Muslim mystics and Western thinkers alike – sets the stage for Ghamidi’s core message: returning to the purity of Quranic teachings without rejecting the wisdom that centuries of scholarship have to offer.

Quran as the Ultimate Criterion – “Al Meezan”

Central to Ghamidi’s approach is the conviction that the Qur’an is the ultimate criterion (furqan or mīzān) for judging all religious ideas filmot.com filmot.com. He often cites the Qur’an’s own words that God “has not just revealed the Book, but also the Balance (al-Mīzān)” filmot.com – a scale to weigh right and wrong – so that people “stay firm on justice” in religious matters. After decades of study, Ghamidi came to realize “the status which Allah Himself has given” the Qur’an: it is the final authority in matters of faith, above human conjectures and sectarian doctrines. This realization crystallized when he became a student of Imam Amin Ahsan Islahi (himself a disciple of the famed scholar Hamiduddin Farahi) in 1973. Under Islahi’s mentorship, Ghamidi decided to dedicate himself exclusively to the Qur’an, recognizing it as the touchstone against which all religious teachings must be tested.

Ghamidi describes how, from that point on, he “mercilessly scrutinized” every inherited idea – be it classical jurisprudence, theological opinions, or mystical tenets – by testing them on the standard of the Quran. He spent decades filtering Islam’s vast intellectual tradition through this Quranic lens, an effort culminating in his own 5-volume Qur’an commentary (Al-Bayān) and treatise Mīzān (Balance). The result of this rigor is a nuanced position: Ghamidi upholds only those beliefs and practices that clearly align with the Qur’an (and authentic prophetic example), while setting aside accretions that lack Quranic basis. Crucially, this method does not entail discarding all scholarship; rather, it involves engaging with scholarship critically, accepting or adapting insights that are in harmony with scripture and gently pruning away those that contradict it.

For example, when examining Sufi concepts such as the idea of special “friends of God” (awliyā) wielding spiritual powers or intercession, Ghamidi concludes that no such doctrine is endorsed by the Qur’an. “The whole Quran is completely bereft of the concept of wilāyah (sainthood as a rank), there is not even a hint of it,” he asserts. The Qur’anic term walī (friend/guardian) is used only in a general sense – for God as protector and for all faithful believers as His friends – never to establish a hierarchy of saints. Titles like Qutb, Ghaus, Autād, Nujabā (ranks in Sufi cosmology) are absent from the Quranic vocabulary. Ghamidi argues that this elaborate mystical hierarchy arose much later in Islamic history, effectively creating “a parallel system” of spirituality outside the Prophet’s Islam. By shining the Quranic light on such ideas, he does not demean the piety or good intentions of the sages who taught them, but he gently re-centers the discourse: any path to God must stay within the bounds of Qur’an and Sunnah, without secret doctrines or intermediaries beyond what the scripture itself sanctions.

This Quran-as-criterion approach extends to all areas of Islam. Ghamidi separates Shariah (Divine law) from Fiqh (jurists’ interpretations), noting that much of what Muslims consider “Islamic law” is actually human extrapolation that can evolve with time thequran.love thequran.love. The Qur’an and proven Prophetic teachings form the immutable core, but later opinions – even by revered imams – must be open to re-evaluation under the Quran’s guidance. In Ghamidi’s view, Islam is a timeless framework of moral principles (e.g. justice, compassion, monotheism, afterlife accountability), not a frozen code of seventh-century ordinances thequran.love thequran.love. He often highlights that the Qur’an itself contains no fixed political system or detailed economic blueprint for all times; it imparts enduring values instead thequran.love. Even if one were to infer a governance model from early Islamic history, “it would be for the circumstances of seventh-century Arabia…not in the context of the present-day global village” thequran.love. Thus, any socio-political rulings mentioned in the Quran must be understood in their original context and applied through the prism of those universal principles today. I would augment Ghamidi’s approach by saying – those who dream of literally enforcing medieval interpretations of Shariah in the modern age, “I have a bridge to sell them in New York” – underscores with humor that a slavishly literal approach is untenable thequran.love. The seriousness behind the jest is his deep reverence for the Qur’an: “I honor it, so I want to understand it precisely and personally, rather than delegating this to others” thequran.love. In other words, treating the Quran as a living, relevant guidance is itself an act of devotion; it demands both humility before the text and courage to revisit our inherited understandings.

Appreciating Sufi Devotion and Other Scholarly Contributions

Despite his critical eye, Ghamidi does not reject the rich heritage of Islamic scholarship and spirituality – he only recalibrates it. In the video, he reminisces fondly about the spiritual intensity of Sufi practices he witnessed, and the uplifting impact of Sufi poetry and legends in his youth filmot.comfilmot.com. This early love for Sufi literature gave him “pleasure and joy” and even a “source of contemplation and understanding” in formative yearsfilmot.comfilmot.com. Such reflections show Ghamidi’s gratitude for how Sufism nurtured personal piety and moral discipline. He acknowledges that many Muslim societies were kept attached to the faith through the personal example of Sufi saints – their asceticism, generosity, and focus on God’s love often softened hearts more than dry legalism could. In fact, Ghamidi interprets the aim of Islam itself as cultivating excellent morals and God-consciousness in individuals: “the Deen takes our moral behavior to its perfection…to ultimately create certain attributes in us,” as taught in a famous hadith about the Prophet’s mission to perfect characterfilmot.comfilmot.com. Sufi teachings historically aimed at this inner purification (tazkiyah) and sense of ihsan (worshipping God as if seeing Him), which are unquestionably part of Islam’s ethos. Thus, Ghamidi appreciates these positive aspects of Tasawwuf – the emphasis on remembrance of God, sincerity in worship, and a direct personal connection with the Divine – so long as they do not introduce new dogmas absent in scripture.

Likewise, Ghamidi remains deeply respectful towards the classical scholars and jurists of Islam. He often quotes heavyweights like Imam Abu Hanifa, Shafi‘i, Ghazali, Ibn Taymiyyah, etc., not to disparage them but to engage in a dialogue across centuries. His own teacher, Imam Islahi, was a traditional scholar, and Ghamidi’s methodology (called Farahi-Islahi school) builds on classical Quranic exegesis principles. When Ghamidi parted ways with his first mentor Maulana Maududi (founder of Jamaat-e-Islami) over political ideology, he still “maintained deep respect” for Maududi’s contributions thequran.love thequran.love. He credits Maududi for significant insight, even as he disagreed with the Islamist notion that establishing an Islamic state is the primary religious obligation thequran.love. This balance of esteem coupled with independent reasoning is a hallmark of Ghamidi’s engagement with past scholars: he stands on their shoulders to see farther, rather than knocking them down. In essence, Ghamidi exemplifies how one can keep the Qur’anic understanding pure – free of superstition or sectarian distortion – without rejecting the intellectual and spiritual wealth that Muslim civilization has amassed. He acts as a bridge between the purists and the mystics, appreciating the truths each hold while filtering all through the Qur’an’s criterion.

Importantly, Ghamidi’s openness extends to non-Muslim scholarship as well. He frequently references world history and philosophy in his talks, demonstrating familiarity with thinkers from Socrates and Confucius to modern Western philosophers. By citing Aristotle and Plato in comparison to Prophetic wisdomfilmot.com, he implicitly acknowledges that wisdom is not the monopoly of any one civilization. He draws a line only where revelations begin – i.e. no philosopher’s conjecture can equal a Prophet’s message – but he certainly encourages learning from all human experiences. This resonates with the Qur’anic ethos of reflecting on the world and seeking wisdom wherever it may be found. Indeed, one of Ghamidi’s oft-quoted maxims is that faith (īmān) and wisdom (ḥikmah) are “twin lights” that must work together. Thus, he does not shy away from secular knowledge or Western thought; rather, he absorbs what is beneficial and ethically sound from it. For example, Ghamidi is a vocal proponent of universal human rights, education, and rational inquiry – values also championed by Enlightenment philosophers khalidzaheer.com thequran.love. He interprets Islamic teachings in a way that upholds fundamental human dignity (freedom of belief, equality, justice), showing harmony between Quranic principles and the best of modern ethical ideals. In summary, Ghamidi’s stance is not one of isolationism; it is integrationist – he invites all knowledge streams to enrich our understanding of God’s message, provided the Qur’an’s primacy is acknowledged.

Reflections – Integrating All Human Scholarship to Understand the Quran

In spirit, I find strong common ground with Ghamidi on the core tenets of Islam. Like him, I firmly uphold tawḥīd (the oneness of God) and the authenticity of the Prophet’s message, as well as the reality of the Ākhirah (Hereafter) as fundamental, non-negotiable truths. These transcend time and context – they form the eternal theology of Islam on which we do not compromise. However, when it comes to interpreting “the rest of the Qur’an” – the vast guidance it offers on social affairs, legal matters, nature, and human psychology – I believe, much as Ghamidi does, that context and reason are essential. In fact, I would take the approach even further: we should bring all of human scholarship into conversation with the Qur’an to unlock its fullest understanding. The Qur’an addresses all spheres of human life; therefore, insights from science, history, philosophy, sociology, and other religions can greatly enhance our comprehension of the scripture’s intent in these areas.

Ghamidi himself acknowledges that Muslims must read the Qur’an as a living document, not a text “written in stone.” As he and many scholars note, the Qur’an was revealed in 7th-century Arabia, in a milieu of camels and date palms – naturally it employs the metaphors and presupposes the knowledge of that era thequran.love thequran.love. This historical situatedness is not a flaw but a key to understanding the Quranic message. “Context is king,” as one of my earlier essays emphasized thequran.love. We observe, for instance, that the Quran mentions camels but not cars, dates but not mangoes thequran.love thequran.love, simply because its first audience knew camels and dates intimately, whereas automobiles or South Asian fruits lay outside their world. The All-Knowing God chose references meaningful to that audience – “not because God did not know about [future things], but because the seventh-century Arabs…did not know” themthequran.love. Appreciating this point guards us from overly literal readings. It would be a mistake to think that piety today requires riding a camel instead of a car, or structuring society exactly like 7th-century tribal Arabia. What God’s message requires is extracting the principles (e.g. be grateful for God’s provisions, use available means responsibly, etc.) and applying them in our own context. Ghamidi echoes this reasoning by stating that if even a political or economic norm seems described in the Qur’an, it was addressing that time’s needs – those norms “may not be literally applicable to [our] present situations”thequran.love. I wholeheartedly concur: the Quran’s moral and spiritual guidance is timeless, but its social injunctions often depend on context and should be re-examined under present realities.

History bears out this adaptive understanding. Virtually all Muslim scholars today recognize certain Quranic laws are context-dependent, even if they don’t always say so bluntly. For example, the Qur’an spoke of treating captured slaves or concubines in specific ways – yet “every Muslim scholar worth anything today” admits those verses have “no present-day application” because the institution of slavery itself has vanishedthequran.lovethequran.love. Similarly, the Qur’an permitted polygamy in a society with frequent warfare and orphans, but many modern scholars argue that the Quranic ethos actually leans toward monogamy or very restricted polygamy given today’s normsthequran.love. Punishments like cutting off a thief’s hand are in the text, but practically all jurists now prefer a metaphorical or alternative implementation (e.g. imprisonment), recognizing the changed sensibilities of justice – “many understand that…in our contemporary times [such verses] can be implemented metaphorically”thequran.love. These are profound shifts from a literalist approach, all prompted by engagement with human knowledge and changing context. In earlier centuries, it was often the jurists’ own life experience and intuition of societal benefit (maṣlaḥa) that guided such flexibility. Today, we have far more to draw on: scientific discoveries, advancements in ethics and law, and historical hindsight. We should confidently utilize these tools to inform our tafsīr (exegesis). In doing so, we actually follow the Prophet’s example of wisdom – he applied revelation to his context; we must apply it to ours, using the best knowledge at our disposal.

In my writings, I have advocated a harmonization of Quranic understanding with modern science and rational inquiry. Ghamidi cautions (rightly) that the Qur’an is “fundamentally a book of guidance…not a scientific manual”, so we should not force scientific theories onto verses in a way that distorts the scripture’s primary messagethequran.love. He warns that the Qur’an’s language can be allegorical and that chasing “scientific miracles” in it may lead to misinterpretationthequran.love. I agree with his caution – the Qur’an was never meant to be a textbook of astronomy or biology. However, I see science as a powerful ally in understanding the Quran’s metaphors and references to nature. The Qur’an repeatedly invites us to observe the natural world as signs of God; thus, learning modern science can deepen our awe of those signs. Where Ghamidi might stop at saying “the Quran is not about science,” I go a step further to say: the Quran encourages science – it “inspires believers to study nature”, as evidenced by hundreds of verses urging reflection on creationthequran.love. For example, when the Qur’an describes all living things being made from water, or the heavens and earth once being a joined entity (Big Bang-like), these can harmonize beautifully with scientific knowledge if handled carefully. My approach has been to polish our understanding of the Quran by the light of scientific insights, not to read science into the Quran artificially, but to see where scientific reality and Quranic symbolism converge. This is why our project catalogs verses relating to nature and encourages studying them alongside scientific findingsthequran.love. We maintain, for instance, a compilation of 750+ Quranic verses that inspire scientific explorationthequran.love and 300 verses about compassionate livingthequran.love – showing that faith and reason cooperate to bring out the Quran’s rich guidance for both the physical and moral realms.

Bringing “all of human scholarship” to bear also means engaging with philosophy, sociology, and humanities when reading the Qur’an. If the Qur’an talks about social justice, why not consult the vast literature on ethics and political theory to see how those eternal Quranic values can best be applied today? If the Qur’an relates stories of past nations, archaeology and anthropology can shed light on their context. This doesn’t undermine the Qur’an’s message – it illuminates it. As Sir Francis Bacon wisely said, we should “read not to contradict… but to weigh and consider”thequran.love. Using the weight of all available knowledge helps us consider the Quranic verses from multiple angles, leading to a more balanced and thoughtful interpretation. In one of my articles, I argued that sometimes Muslims treat certain verses as if “written in stone” – refusing to reinterpret them despite new evidence – whereas other verses they are willing to treat as if “on paper,” adaptable to new understandingthequran.love. This inconsistency is intellectually untenable and even unjust to the scripture. Every verse of the Qur’an must be pondered with our best wisdom, not fossilized by past precedentsthequran.love. Otherwise, as I cautioned, we end up blaming God for our own shortsightedness – sects argue that their rival’s views are “wrong” per God’s word, when in fact it may be their own rigid reading at faultthequran.love. Ghamidi’s push to personally engage with the Quran, rather than blindly “delegating” understanding to clergymen of the past, is precisely what frees us to employ reason and research in interpretationthequran.love. It empowers individual scholars and laypersons alike to reinterpret archaic rulings in the fresh air of current knowledge – just as Cairo University’s modernist president recently urged scholars to “scrap [obsolete] heritage… made to suit a different age” in favor of renewed religious thoughtthequran.lovethequran.love.

To be clear, expanding the toolkit of Quranic interpretation to include all human scholarship does not mean altering core beliefs or compromising the sacred text. It means deepening our understanding of the Qur’an’s guidance in worldly matters so that Islam can truly be “a mercy for all mankind” in the 21st century and beyond. Ghamidi and I both desire to see Muslims rise above insular thinking and engage with the broader intellectual world. He demonstrates this by respecting diverse viewpoints and insisting on justice and compassion as Quranic essentials. I strive to complement this by actively incorporating scientific and philosophical insights to enrich our comprehension of divine guidance. In effect, we are in harmony on fundamentals – unity of God, primacy of revelation, necessity of virtue – and any divergence is in emphasis: I place slightly more stress on modern knowledge as a partner in Quranic exegesis, whereas Ghamidi focuses on shielding Quranic purity from human innovations. Yet even in this difference, we are not at odds: both approaches call for using one’s God-given intellect earnestly. After all, the Qur’an repeatedly challenges “Will you not reason?” and “Will you not consider?”.

Conclusion

Javed Ghamidi’s approach exemplifies a delicate but vital balance in contemporary Islamic thought: Remain rooted in the pure message of the Qur’an, but do not cut off the roots of wisdom that grow outside your own tradition. He honors the legacy of Muslim scholarship – from jurists to Sufi saints – without hesitating to prune their views against the standard of God’s Bookfilmot.comfilmot.com. He engages with Western philosophers and modern ideas, yet keeps the Qur’an and Prophet’s example as the anchor of truthfilmot.comfilmot.com. In my own intellectual and spiritual journey, I echo Ghamidi’s reverence for the Qur’an’s authority and embrace his inclusive spirit, agreeing with him broadly on the foundational beliefs that define our faith. And building upon the path he illuminates, I believe that all knowledge – scientific discoveries, historical insights, philosophical wisdom – can serve as handmaids to the Qur’an, helping reveal its timeless guidance in our ever-changing world. This holistic engagement with “all human scholarship” is, to me, not a departure from keeping the Qur’anic understanding pure, but rather the fulfillment of it. It prevents a narrow or literalist reading and instead allows the Qur’an’s true objectives – justice, compassion, enlightenment, and God-consciousness – to shine through in every agethequran.lovethequran.love. Ghamidi often emphasizes that the Quran “has been revealed as a balance” so that people do not go astrayfilmot.comfilmot.com. By balancing fidelity to revelation with openness to human knowledge, we ensure that our understanding of Islam remains both pure in its essence and rich in its application. This, ultimately, is a formula for a vibrant, authentic, and compassionate Islam – one that cherishes its scripture as divine guidance and welcomes truth from every direction as further clarification of that guidance.

References: Javed A. Ghamidi’s interview on Tasawwuf (Sufism)filmot.comfilmot.com; Zia H. Shah, “Sometimes the Quran is Written on Stone and Often on Paper”thequran.lovethequran.love; Zia H. Shah, “Some Argue Islamism… and Many Argue Both on the Same Day”thequran.lovethequran.love; Zia H. Shah, “The Holy Quran and the Seventh Century Arabian Metaphors”thequran.lovethequran.love; Zia H. Shah, “Both Agreeing and Disagreeing with Javed Ahmed Ghamidi”thequran.lovethequran.love. Each of these sources has informed the analysis above, illustrating how maintaining Quranic purity and embracing broad scholarship go hand in hand in the quest to truly “weigh and consider” the message of the Quran in our timethequran.love.

Leave a reply to Hindsight Is 20/20: From Sectarian Monopoly to Inclusive Quranic Scholarship – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply