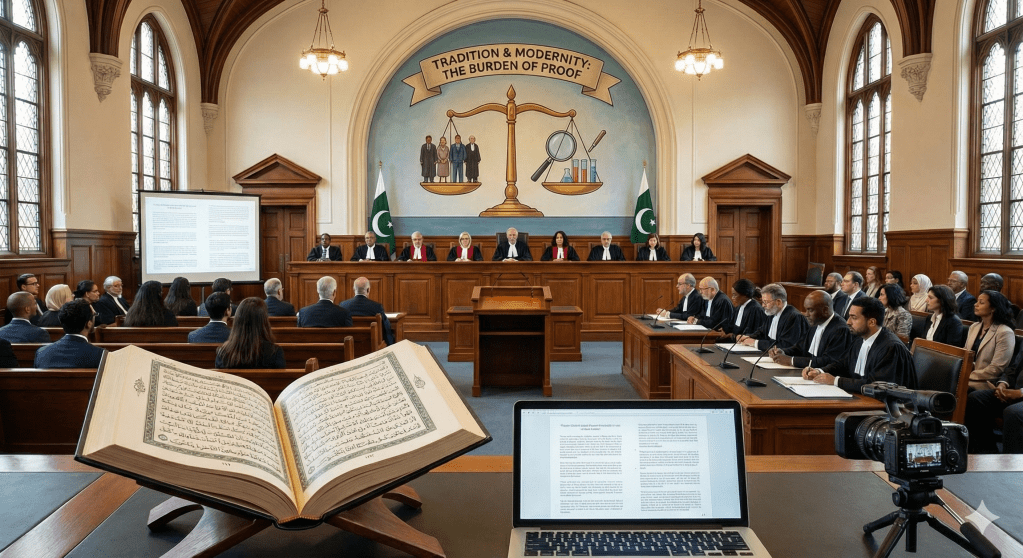

Epigraph

لَا إِكْرَاهَ فِي الدِّينِ ۖ قَد تَّبَيَّنَ الرُّشْدُ مِنَ الْغَيِّ ۚ فَمَن يَكْفُرْ بِالطَّاغُوتِ وَيُؤْمِن بِاللَّهِ فَقَدِ اسْتَمْسَكَ بِالْعُرْوَةِ الْوُثْقَىٰ لَا انفِصَامَ لَهَا ۗ وَاللَّهُ سَمِيعٌ عَلِيمٌ

Al Quran 2:256

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

Freedom of thought and religion is a cornerstone of human dignity and intellectual progress. This essay explores the importance of this freedom from psychological, philosophical, and theological angles, drawing on Quranic teachings and modern human rights principles. It argues that genuine faith and truth-seeking flourish only in an environment without coercion. Foundational religious texts – exemplified by Quranic verses like “There is no compulsion in religion” – and documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirm the right to individual belief. Yet history shows that organized religions often violate this ideal, from medieval heresy trials and crusades to contemporary extremist enforcement of doctrine. Through examples from Christianity and Islam, we illustrate how institutional religion has sometimes suppressed freedom of conscience, and we highlight the enduring need to uphold each person’s right to think and believe freely. A concluding thematic epilogue reflects on restoring the true spirit of faith and tolerance in our global society.

The Psychological Need for Freedom of Thought

Psychologically, the freedom to form one’s own thoughts and beliefs is fundamental to mental well-being and identity. Human beings have an innate need for autonomy – the sense that our convictions are authentically our own. When external authorities force individuals to conform in matters of belief, it can lead to intense cognitive dissonance and stress. People may outwardly profess what is demanded while privately questioning or disagreeing, a state of “preference falsification” that erodes integrity and trust. In contrast, when individuals are free to explore ideas without fear, they experience greater honesty with themselves and others, which is crucial for psychological health. As one psychologist noted, “We need freedom of thought and freedom of speech to create the healthy climate of ideas that is core to the work of creating a healthy world.” Suppressing someone’s sincere beliefs not only damages that person’s sense of self, but also creates communities built on fear and hypocrisy rather than genuine conviction.

Moreover, intellectual freedom stimulates personal growth and learning. Creativity and moral reasoning thrive in an open environment where questioning is allowed. When religious or ideological systems stifle any doubt or dissent, they may produce outward conformity at the cost of inner resentment or confusion. Psychologically, coerced belief can never be wholehearted – a mind compelled by fear is not truly convinced. This often leads to either eventual rebellion (when the person finally rejects the imposed beliefs) or a harmful loss of individual critical thinking. In either case, the person’s mental and emotional development is hindered. Thus, from a psychological standpoint, respecting freedom of thought and religion is essential for nurturing healthy, authentic individuals and societies.

Philosophical Foundations of Religious Freedom

Philosophers and ethical thinkers have long championed freedom of thought and belief as a fundamental right. Classical liberal philosophy, emerging from the Enlightenment, argued that truth can only emerge from free inquiry and that coercion in matters of conscience is unjust. John Locke, in his Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), famously contended that genuine faith cannot be forced: “All the life and power of true religion consist in the inward and full persuasion of the mind; and faith is not faith without believing.” In other words, belief has value only if it is embraced voluntarily, not under compulsion. Locke and others drew a sharp line between the role of the state and the church, insisting that the state has no authority to dictate personal convictions. True religion, Locke argued, is a matter of inward conviction and cannot be imposed by swords or laws without emptying it of sincerity.

Subsequent philosophers built on these ideas. Voltaire championed religious tolerance, and John Stuart Mill asserted in On Liberty (1859) that silencing any opinion is an injustice to humanity – if the opinion is right, the world is deprived of truth; if wrong, the world loses a deeper understanding of truth through its refutation. The marketplace of ideas concept holds that only in freedom can ideas be tested and refined. Thus, from a philosophical viewpoint, enforcing a singular “orthodoxy” is counterproductive: it shields falsehood from challenge and deprives individuals of their moral agency. Autonomy of conscience is seen as an inalienable right – each person must be free to pursue truth as their reason and conscience guide them. These principles later influenced modern democratic values and were enshrined in international human rights charters, reflecting a broad consensus that freedom of thought and religion is essential for a just and enlightened society.

Theological Insights: Freedom of Religion in Scripture

Perhaps surprisingly to some, the ideal of freedom of religion is deeply rooted in theological sources – especially in the Islamic tradition. The Quran explicitly enjoins that faith cannot be imposed: “There should be no compulsion in religion. Surely, right has become distinct from wrong…” (Quran 2:256). This verse establishes that guidance must be chosen freely; truth stands clear from error, so one must embrace it by conviction, not by force. The very next verse reminds us of God’s sovereignty over the universe (Ayat al-Kursi, 2:255), implying that while God is all-powerful, He does not compel belief in this worldly life – leaving humans to exercise free will. Throughout the Quran, the Prophets are described as messengers whose duty is only to convey the message, not to control or compel their audience. For example, God tells Prophet Muhammad: “If they turn away, your duty is only to convey the Message; and Allah is All-Seeing of His servants.” (Quran 3:20). Similarly, “But if they turn away, [O Prophet,] your only responsibility is clear communication [of the message].” (Quran 16:82)islamawakened.com. Over and over (in verses 5:99, 13:40, 16:35, 24:54, 42:48, etc.), the Quran emphasizes that the Prophet is not an enforcer of faith, only a warner and bearer of glad tidings. Belief is a matter of the heart and cannot be genuine under duress.

This principle is illustrated vividly in Quranic narratives. Surah Ya-Sin (36:13–25) relates the story of a town that received messengers calling them to God. The people rejected the prophets, and one righteous man urged his fellow citizens, “Follow the messengers!” (36:20). Tragically, his people killed him for his faith, and he attained martyrdom – saying, “If only my people knew how my Lord has forgiven me.” (36:26-27). Notably, the messengers did not retaliate by force; the punishment for the town’s obstinate unbelief came only as a matter of God’s judgment, not human coercion. This story underscores that acceptance of faith was left to the people’s own choice, even though they chose violently to reject it. Likewise, in Surah Al-Ghashiyah, the Prophet is instructed: “So remind [them]; you are only a reminder. You are not a taskmaster over them.” (Quran 88:21-22)surahquran.com. Here the Quranic language could not be clearer – the Prophet (and by extension any preacher) is not an authority to compel belief. The inner journey of faith is each soul’s responsibility, and ultimate accountability lies with God alone: “your duty is only to deliver the message, and on Us is the reckoning” (Quran 13:40).

In the Christian scriptures, one can find a similar spirit of voluntary faith, even if it was not always heeded by later institutions. The New Testament portrays Jesus never coercing anyone – he taught, persuaded, and invited: “If anyone will not welcome you or listen to your words, leave that home or town and shake the dust off your feet.” (Matthew 10:14). Early Christians for the first few centuries had no temporal power and themselves demanded freedom to worship without persecution. Unfortunately, as we will see, when Christianity later became organized under imperial power, it often departed from this early ideal. Nonetheless, theologically one can argue that God values sincere belief, and sincerity is only possible if a person has the liberty to disbelieve. Any attempt by religious authorities to enforce belief is not only a violation of human freedom but a usurpation of God’s role as ultimate judge of hearts.

Freedom of Belief in the Modern Human Rights Framework

In the modern era, the principle of freedom of thought, conscience, and religion has been affirmed as a universal human right. The most prominent statement of this is Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which proclaims: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”. This far-reaching definition protects not only the right to hold any belief or none, but also the right to change one’s religion and to practice it openly. Importantly, Article 18 also forbids coercion in matters of faith, stating that no one shall be subject to force that impairs their freedom to adopt a belief of their choosing. These rights were formulated in response to the atrocities of the past – from religious persecutions to the horrors of World War II – under the conviction that respecting individual conscience is essential to peace and human dignity.

Today, nearly all nations profess commitment to these principles, at least on paper. International treaties like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) further enshrine freedom of religion and belief, making it binding on signatory states. In theory, organized religions also endorse these values – many religious leaders extol the importance of conscience and the idea that “faith by force” is invalid. However, the challenge has been in practice. The UDHR ideal stands in contrast to the realities in many parts of the world where blasphemy and apostasy are criminalized, or where social pressures effectively coerce religious conformity. Nonetheless, the UDHR provides a powerful ethical benchmark. It connects back to the theological concept that belief must be uncoerced, and to the philosophical notion that every individual has sovereignty over their own mind. Thus, international human rights law and diverse moral traditions converge on a shared truth: freedom of thought and religion is inviolable and must be defended against any who would suppress it.

Organized Religion and the Suppression of Free Belief

While ideals of religious freedom are often affirmed in principle, history shows that organized religions – when fused with temporal power – have frequently opposed this ideal. Across different eras and faith traditions, religious authorities have at times enforced their doctrines on individuals, through methods ranging from subtle social pressure to outright violence. This tendency arises when a sect or church gains institutional dominance and seeks to preserve its authority by silencing dissent or competition. Heresy hunting, crusades, inquisitions, and other forms of coercion are tragic manifestations of this impulse. Below we examine examples from Christianity and Islam, illustrating how even religions that preach compassion and truth can fall into the trap of compulsion when human power and zealotry take over.

Read further in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment