Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

Buddhism’s attitude toward divinity has undergone a complex evolution over millennia. Early Buddhism emerged in a milieu saturated with gods and divine beliefs, and while it acknowledged numerous deities, it rejected the notion of an almighty creator. Over time, Buddhist thought moved increasingly toward a non-theistic or even explicitly atheistic framework, emphasizing impersonal laws (karma, dependent origination) over divine agency. This essay explores that transition from multiple perspectives – historical developments, psychological motives, theological shifts, and philosophical arguments – and provides scholarly evidence of theistic elements in early Buddhism alongside analyses of how and why later Buddhism minimized or refuted the role of gods. Contemporary Buddhist traditions are also examined, revealing that some (such as Pure Land and Tibetan Buddhism) retain strong devotional or theistic-like elements, even as the core doctrinal stance of Buddhism remains non-theistic. An epilogue reflects on what this evolution from a theistic context to an atheistic philosophy means for our broader understanding of religion and metaphysics.

Introduction

Buddhism is often described as a religion without a God, a spiritual path that does not center on an all-powerful creator or supreme being. This characterization, however, belies the nuanced reality that Buddhism’s own scriptures and practices are populated with divine beings, heavens, and devotional elements – especially in its early and popular forms. How, then, did Buddhism come to be seen as atheistic? To answer this, we must trace Buddhism’s evolution from its origins in ancient India (where it coexisted with theistic Hindu traditions) through its development across Asia, analyzing changes in doctrine and practice. In the sections that follow, we provide a historical overview of Buddhism’s stance on gods, examine the psychological and cultural factors influencing Buddhist religiosity, analyze theological and philosophical shifts regarding the concept of the divine, present evidence of early Buddhist theism, and discuss the transition toward a non-theistic outlook. We then consider modern Buddhist schools that retain theistic characteristics and conclude with reflections on the broader implications of Buddhism’s journey from theism to non-theism.

Historical Trajectory: From Theistic Origins to Non-Theistic Philosophy

Buddhism arose in the 5th century BCE in a region and era steeped in theistic beliefs. Early Buddhists did not outright deny the existence of gods – in fact, the Pāli Canon frequently mentions various deities (such as Indra (Sakka) and Brahmā) interacting with the Buddha. The Buddha is even honored as a “teacher of gods and men”, indicating that devas (gods) were understood as real beings who could learn from him. One famous account describes the deva Brahmā Sahampati imploring the newly enlightened Buddha to teach the Dharma to the world – a scene that underscores both the existence of a high god and the Buddha’s superior role as teacher (the god bows to the Buddha’s wisdom). Early Buddhism thus accepted the existence of devas, but crucially, it redefined their status: these gods were neither creators of the cosmos nor immortal beings, but merely another class of sentient beings subject to rebirth and death. In Buddhist cosmology, gods reside in various heavenly realms, yet they are impermanent and ultimately in need of the Buddha’s guidance for liberation.

In its earliest doctrinal stance, Buddhism was notably silent or agnostic about any creator deity. The Buddha did not preach about a single omnipotent God; instead, he focused on practical methods to end suffering. When pressed on metaphysical questions (including the origin of the universe or the existence of a creator), he often remained non-committal or dismissive, steering the discussion back to the Four Noble Truths. Scholars note that in the early texts the Buddha comes across less as a doctrinaire atheist and more as a skeptic who finds such speculative views irrelevant to liberation. Richard Hayes, a historian of Buddhism, observes that early Buddhist suttas treat the question of a creator “primarily from either an epistemological point of view or a moral point of view,” rather than making flat denials. In other words, the Buddha’s concern was not to prove gods false, but to show that believing in a creator or relying on divine grace did not lead to the highest good – only one’s own enlightenment efforts did.

Significantly, the Buddha did criticize certain theistic doctrines on ethical grounds. In one scripture, he explicitly rejects the idea that all one’s experiences are “due to the creation of a supreme deity” (Issara)—calling this view fatalistic because it would make moral effort meaningless. He argued that if people believed a God controlled everything, they might shrug off responsibility for evil deeds (“men will become murderers, thieves… and claim it is due to the creation of a god,” the Buddha warns). In another discourse, the Buddha uses the problem of suffering to challenge the idea of a benevolent creator: if a Supreme God made the world, then the intense pain some beings endure implies that this creator must be cruel or unjust. These early teachings show the Buddha pushing back against theistic explanations in favor of a moral-law explanation (karma) – without necessarily denying that gods exist, he denies they have ultimate control or provide a valid basis for ethics.

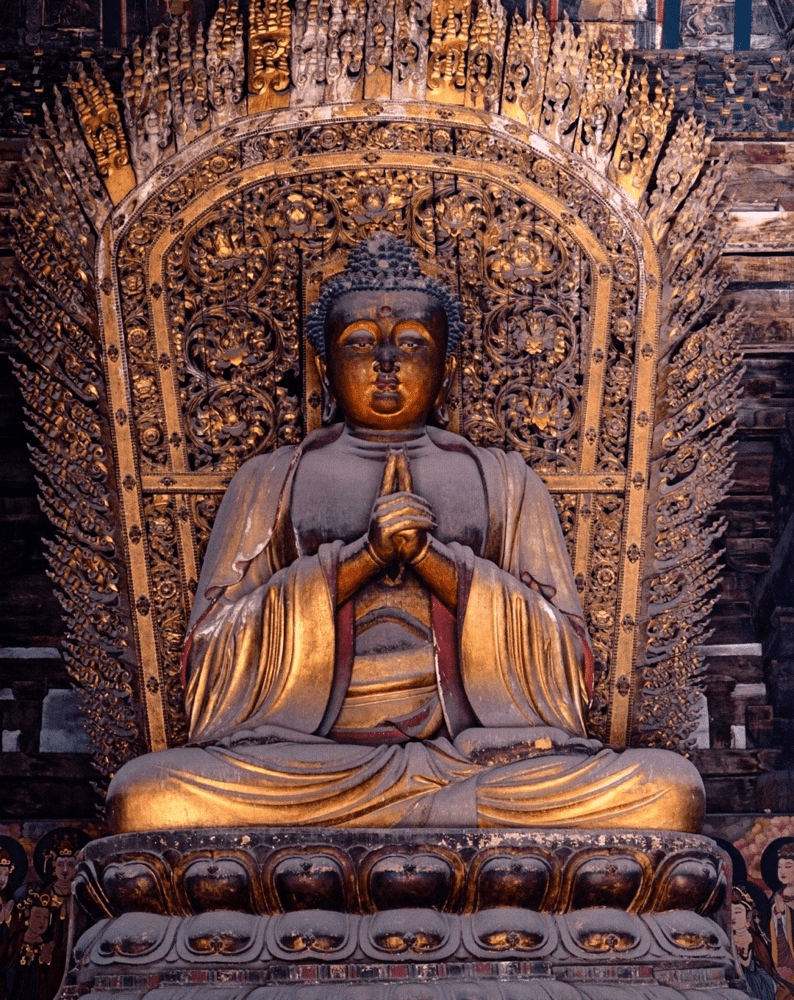

As Buddhism spread beyond India (to Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, East Asia, and Tibet), it encountered new religious environments and evolved in response. Regionally distinct forms of Buddhism emerged, each interacting with local beliefs. In India itself, over the first millennium CE, Mahāyāna Buddhism developed new doctrines that, somewhat paradoxically, introduced more exalted quasi-divine figures (celestial Buddhas and Bodhisattvas) even while Buddhist philosophers articulated sharper critiques of theism. Mahāyāna sutras present cosmic Buddhas like Amitābha and Vairocana who are described with infinite wisdom, supernatural powers, and eternal life-spans, attributes that invite comparison with theistic god-concepts. For example, Amitābha Buddha is said to have created a “Pure Land” paradise for his devotees, and the Buddha Vairocana is depicted as a cosmic, all-pervading being whose light fills the universe. Such descriptions led some scholars to label aspects of Mahāyana as pantheistic or panentheistic, since the ultimate reality (Buddha-nature or Dharmakāya) in these texts can resemble a divine essence immanent in all things. In East Asia, sects like Huayan Buddhism explicitly portrayed Vairocana as a cosmic Buddha embracing all of existence, a vision strikingly similar to a godhead that is everywhere and eternal.

Yet, despite this proliferation of divine imagery in later Buddhism, the religion’s philosophical core shifted further away from theism. During the medieval period in India (c. 5th–11th centuries), Buddhist scholars engaged in vigorous debates with Hindu theologians who posited a creator Īśvara or Brahman. In response, Buddhists like Vasubandhu (5th century) and Dharmakīrti (7th century) penned detailed refutations of creationism and Hindu theism. These philosophers argued, for instance, that the idea of a single permanent cause (God) producing a transient world is logically untenable – if an eternal God were the sole cause, the effect (the world) should have no beginning and all events would occur at once, which contradicts observation. They also contended that karma and dependent origination sufficed to explain the universe without invoking a deity. By accepting only natural causation, Buddhism in this phase took on a self-consciously atheistic stance. Indeed, modern scholars note that this later stage of Buddhist thought can be described as “anti-theistic,” given its systematic rejection of a creator concept. Even the orthodox Theravāda tradition, which is generally conservative, explicitly upheld non-theism in its commentaries – the 5th-century Theravāda scholar Buddhaghosa wrote, “There is no god Brahmā [as creator]. The phenomena alone flow on”, affirming that only natural phenomena and conditions (not divine will) account for the world.

In summary, the historical arc of Buddhism shows an initial willingness to work within a theistic cosmology (populated by many gods) but a deliberate avoidance of granting those gods any creative or salvific preeminence. As Buddhism matured, especially through intellectual debates and cross-cultural exchanges, it increasingly clarified its non-theistic principles – placing Dharma (law, truth) in the role that a creator God holds in theistic religions. By the modern era, many Buddhist leaders and reformers (particularly engaging with Western audiences) have emphasized that Buddhism is a “religion without God”, highlighting its rational, empirical approach to spiritual liberation.

Psychological Dimensions of the Shift

Beyond doctrinal history, psychological factors played a significant role in Buddhism’s evolution from theism toward non-theism. At its heart, Buddhism offers a path of personal practice and insight – it teaches that each individual is responsible for their own awakening (enlightenment) through ethical living and meditation. This emphasis fosters an internal locus of control: followers look inward to understand and overcome suffering rather than appealing to an external deity for salvation. Psychologically, this was a radical shift from the prevailing religious mindset in ancient India, where devotion to gods and dependence on divine favor were common. The Buddha’s teachings gave people a sense of empowerment and agency; by removing God from the equation, practitioners were encouraged to rely on their own effort and mindfulness. This internal focus can fulfill a deep psychological need for autonomy and mastery – adherents find confidence in the idea that liberation is within their own grasp, not contingent on pleasing a god.

However, human psychology is diverse, and not all adherents were satisfied with an austere, impersonal approach. For many, the emotional comfort of devotion and faith in a higher power is hard to relinquish. This helps explain why, even as elite Buddhist philosophy trended toward atheism, devotional forms of Buddhism grew popular among the masses. Traditions like Pure Land Buddhism (in China and Japan) emerged, offering a faith-based practice centered on Amitābha Buddha. In Pure Land practice, devotees chant Amitābha’s name and trust that his grace will ensure their rebirth in his Western Paradise, where enlightenment is easily attained. Psychologically, this is akin to the theistic paradigm of salvation by grace – it taps into the human desire for an external savior who offers hope and reassurance. Pure Land Buddhism demonstrates how, for many people, devotion and faith provide emotional solace that a purely self-powered path might lack. As one scholar notes, having “faith in a Buddha’s divine intervention seems similar in some ways to theistic beliefs and practices in the West”. The crucial difference, of course, is that Amitābha is not a creator or judge but an enlightened guide; nonetheless, from a worshipper’s perspective, the practice feels theistic in its reliance on a compassionate transcendent figure.

Another psychological factor is the tendency to personify abstract ideals. Over time, qualities like Compassion, Wisdom, and Truth – initially taught as principles – became personified in Buddhism as Bodhisattvas and cosmic Buddhas. This personification made it easier for devotees to relate and emotionally connect. It is challenging for the human psyche to revere a concept like “emptiness” or “dependent origination,” but much easier to feel devotion toward Kannon (Guanyin), the Bodhisattva of Mercy, or toward a merciful Buddha. In this way, the mind naturally introduced quasi-theistic elements as objects of devotion, even within a fundamentally non-theistic doctrine. Psychologically, rituals and prayers directed at Buddhas or Bodhisattvas serve similar needs as prayer to a god: offering comfort, a sense of communication with a caring power, and hope for assistance. This does not mean that Buddhism reverted to full theism; rather, it adapted by providing devotional outlets that fulfill emotional needs while still upholding the view that ultimate liberation comes from understanding reality (Dharma), not by divine fiat.

The Western encounter with Buddhism in the 19th–20th centuries added another psychological layer. Many Western converts to Buddhism were individuals disillusioned with their birth religions (often Christianity) and the concept of a personal God. For them, Buddhism’s non-theistic philosophy was a major attraction – it appeared more rational, experiential, and free of dogma. These converts often emphasized the atheistic side of Buddhism, sometimes stripping away even its traditional cosmology. As one observer notes, Western Buddhists have been “the foremost promulgators of the idea that Buddhism is non-theistic,” viewing references to gods and spirits as outdated cultural vestiges to be discarded. This aligns with the psychological motive of distinguishing one’s new worldview from the old: by highlighting Buddhism’s lack of a “Sky God,” Western practitioners solidified their break from theism and embraced a spirituality grounded in inner practice. In effect, Buddhism’s atheistic reputation was reinforced in modern times by an audience psychologically primed to appreciate a spiritually fulfilling path without a deity.

In summary, psychologically, Buddhism’s shift entailed a trade-off: it freed individuals from fear of divine judgment and dependency on divine grace, appealing to reason and self-reliance, but it also had to address the enduring human yearning for devotional relationship and hope. The religion adapted by offering symbolic and compassionate figures (like Amitābha or Tara) and by allowing culturally ingrained devotional practices, all while teaching that these are expedient means rather than ultimate truths. The psychological flexibility of Buddhism – its ability to function both as a philosophical discipline and as a devotional religion – has been key to its spread and longevity.

Theological Shifts: Reimagining the Divine in Buddhism

While Buddhism is not “theistic” in the classical sense, it nevertheless developed its own form of theology – or more properly, Buddhology – to describe ultimate reality and the status of enlightened beings. Early Buddhism’s theological stance can be summarized as trans-theistic: it did not revolve around God, but it did posit a transcendent truth (Dharma) and the extraordinary status of Buddhas. Early texts describe the Buddha not as a god, but as a supremely awakened human who has realized timeless truths. In a world where gods existed but were themselves impermanent, the Buddha’s enlightenment represented a higher reality. This led some early Buddhists to quasi-deify the Buddha after his passing – venerating his relics and stupas, and attributing to him qualities that border on the divine (omniscience, miraculous powers, etc.). Still, the theology remained clear: Buddhas are not creators or eternal souls; they are beings who through insight have transcended the cycle of rebirth. Thus, early Buddhist theology replaced a creator God with the concepts of nirvana (the unconditioned state free from suffering) and Dharma (the law/truth discovered by the Buddha) as the ultimate reality.

As Buddhism moved into the Mahāyāna phase, its theology expanded dramatically. Mahāyāna sutras introduced the idea of the “Eternal Buddha” – an aspect of the Buddha that exists beyond time and space. For example, the Lotus Sūtra depicts Shakyamuni Buddha declaring that he actually achieved enlightenment countless eons ago and has merely been appearing in various forms to teach beings, implying an eternal, cosmic Buddha nature. Other texts speak of the Adi-Buddha, a primordially enlightened principle (particularly in esoteric Vajrayana Buddhism). Mahāyāna thus flirts with a theological concept of ultimacy that sounds theistic: an ultimate Buddha or Buddha-nature inherent in all things, omnipresent and inexhaustible. Scholars like Guang Xing have described the Mahāyāna Buddha figure as an “almighty divinity endowed with numerous supernatural attributes”. In Mahāyāna theology, every Buddha in his purified realm can be seen as a kind of creator – not of the whole universe, but of a “Buddha-field” (pure land) where he can aid beings. This is a decentralized theology: multiple Buddhas and Bodhisattvas create enlightened spheres through compassion, rather than one God creating a single world.

Despite these theistic overtones, Mahāyāna theologians took care to avoid violating core Buddhist principles. They explicitly rejected the notion of a singular, independent Creator God who is the source of all that exists. Instead, any creative or salvific act by a Buddha is conditional and localized – a Buddha arranges a pure land in response to beings’ karma and vows, but this happens within the framework of dependent origination, not by absolute fiat. Furthermore, Mahāyāna often insists that these exalted Buddhas are ultimately empty of inherent existence (like all phenomena), meaning that however godlike they appear, they are not metaphysically fundamental in the way a theist’s God is. For instance, Tibetan Buddhist theology employs doctrines such as Two Truths to say that deities (yidam) are relatively real for meditation purposes, but on the ultimate level, they are manifestations of the mind’s pure nature. This kind of theological non-dualism allows Buddhism to use divine imagery without committing to divine ontology. In Vajrayana practice, a meditator visualizes a deity and identifies with it, only to dissolve the visualization into emptiness – an approach that uses the psychology of theism (aspiring to divine qualities) while affirming Buddhist metaphysics (all forms are empty).

The theology of Buddhism, therefore, evolved to fill roles traditionally occupied by theistic concepts with distinctly Buddhist notions. Karma and Dharma replaced a personal god as the moral and natural order of the cosmos. Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha) was posited as an innate potential for enlightenment present in all beings – analogous to a divine spark, yet not a creator, simply the true reality of mind. In some interpretations, Buddha-nature was even called the “Self” (with a capital S) of all beings, a deliberate redefinition of the Hindu Brahman/Ātman concept into a non-theistic framework of emptiness and compassion. By adopting such ideas, Buddhist thinkers provided something ultimate and sacred (the timeless reality of Buddhahood) to satisfy spiritual yearning, while firmly denying a creator-deity or eternal soul as understood in theistic religions.

In comparing early and later theology: early Buddhism was atheological in that it refused to speculate about God or a first cause, focusing on the Four Noble Truths. Later Buddhism became theologically creative, populating its universe with celestial Buddhas and hidden Buddha-natures, but it maintained an atheistic ground – none of these function as an Ishvara (Lord) in the sense of ruling or fashioning the world. No Buddhist school claims the universe was created by Buddha or that a Buddha governs the law of karma; rather, even Buddhas are subject to the Dharma. This is why some contemporary researchers, like José Ignacio Cabezón, assert that Mahayana Buddhism rejects a universal creator God distinct from the world, even if it accepts that enlightened beings can “co-create” particular worlds through their merit and vows.

Thus, Buddhism’s theological evolution demonstrates a shift in the conception of the ultimate: from personal god(s) to impersonal law, and then to a kind of impersonal divinity (Buddha-nature) or multiplicity of compassionate divinities who nonetheless abide by impersonal truth. It’s a transformation that allowed Buddhism to absorb religious devotion and metaphysical depth without compromising its fundamental rejection of a single omnipotent Creator.

Philosophical Perspectives and Metaphysical Arguments

Philosophically, Buddhism’s stance on theism is grounded in its core doctrines of impermanence (anicca), non-self (anattā), and dependent origination (paṭicca-samuppāda). These principles collectively leave little room for a permanent, independent deity. The idea of an eternal Creator violates impermanence, and the idea of an almighty controlling being contradicts the interdependent nature of phenomena. From early on, the Buddhist philosophical worldview saw the cosmos as beginningless and cyclic, rendering moot the question of a first cause. As noted by Damien Keown, the Buddha taught that the cycle of rebirths extends back “many hundreds of thousands of aeons without discernible beginning”. This concept of an eternal universe with no starting point directly undercuts creationism: if there is no first moment, a Creator’s role in starting the universe is unnecessary. Instead, the existence of the world is explained through causes and conditions unfolding over infinite timeexistentialbuddhist.com.

Buddhist logicians in the first millennium CE further sharpened these points through debate and syllogism. A classic argument preserved in texts (like Nāgārjuna’s critiques and later Śāntideva’s writings) is that a perfect, unchanging God could not produce a changing world – since an unchanging cause cannot suddenly give rise to an effect without itself changing, the notion is incoherent. Moreover, if God is eternal and the cause of all, the world too should be eternal and unchanging, which contradicts observation of change. Another line of reasoning is moral: Dharmakīrti argued that the immense suffering and inequality in the world is better explained by karma (each being inherits the results of their own actions) than by the will of a creator. If a single God were responsible for each being’s fate, that deity would be morally culpable for injustice; karma, by contrast, is an impersonal and exact law that avoids such ethical paradoxes. This dovetailed with the earlier-mentioned Buddhist argument that a creator hypothesis leads to blaming God for evil.

Buddhist philosophers also took an epistemological stance: ultimate reality (nirvāṇa or śūnyatā – emptiness) is beyond concepts, and any fixed idea of God is just another concept that must be let go. In the Devadaha Sutta, the Buddha suggests that clinging to speculative views (including “Is there a God? Is there not?”) is part of the net of attachment that keeps beings in suffering. The proper philosophical approach is to examine experience and realize the non-self nature of all phenomena. If even one’s own soul or identity is an illusion (anattā), then by extension, any personified cosmic Self (like Brahman or God) is also an illusion. In this way, anattā doctrine functions as a philosophical refutation of the Ātman/Brahman concept in the Upanishadic tradition – a concept which in some interpretations is akin to God. Buddhism declared that there is no eternal Self, only changing processes; thus, the universe has no Self either, no ultimate person behind it all. The Brahmajāla Sutta contains a parable (touched on earlier) where a deity named Mahābrahmā falsely believes himself to be the Creator, not realizing his exalted status is temporary and conditioned. This story philosophically conveys that believing in a creator God is a result of ignorance and egotism – even gods can fall prey to it – and that a wise person (or Buddha) sees through this delusion. Notably, the text even depicts Māra (the tempter) as encouraging the Brahmā’s delusion, implying that the belief in a permanent creator is a trap set by the forces of ignorance.

By the late first millennium, Buddhist scholars produced whole treatises aimed at dismantling Nyāya and Vedānta proofs of God. For example, the 11th-century master Ratnakīrti wrote Refutation of Arguments Establishing Īśvara, systematically countering each logical argument for God’s existence then known. He and others demonstrated that phenomena can be explained without resort to a single creator: momentary phenomena arise from preceding moments and from complex interdependencies. This reasoning is underpinned by Occam’s Razor avant la lettre – why multiply entities (postulate a God) when natural law and karma suffice? The philosophical stance solidified that Buddhism is self-consistent without a God hypothesis: it has an ethics (karma), a soteriology (enlightenment), a cosmology (multiple world-systems and rebirth) and an ontology (impermanent events and emptiness) that require no eternal being. In fact, introducing a permanent being would break Buddhist ontology, which holds that all conditioned things are impermanent and devoid of self.

It’s important to note that Buddhism’s atheism is generally non-militant. The Buddha and subsequent teachers did not define their path primarily as “against God” but rather “without God.” In practice, Buddhist societies often found a modus vivendi with theistic practices: people might pray to local gods or Bodhisattvas for mundane aid, but turn to Buddha’s teaching for ultimate liberation. This pragmatic duality meant that philosophical atheism coexisted with popular religiosity without extreme conflict. Buddhism never endorsed a single almighty God, but it also rarely went out of its way to attack religion; instead, it sought to render God irrelevant. As one contemporary scholar put it, in early Buddhism the question of God’s existence is met with epistemological caution – the focus is on ending suffering, and anything not conducive to that is set aside.

In conclusion, the philosophical journey of Buddhism regarding theism involved rigorous application of its fundamental insights to the concept of God. Impermanence undermined the notion of an eternal deity; interdependence obviated an independent creator; and the focus on experiential wisdom made speculative theology a distraction. Over the centuries, Buddhist philosophers fortified these points with logical arguments and critiques, culminating in a robust intellectual tradition that portrays belief in God as a misinterpretation of reality, arising from human desires or cosmic misunderstanding. By firmly establishing a worldview where liberation and cosmology operate lawfully without a lawgiver, Buddhism completed its evolution into a thoroughly atheistic philosophical system, even as it retained a rich tapestry of mythology and ritual for skillful means.

Surviving Theistic Elements in Contemporary Buddhism

Despite Buddhism’s doctrinal non-theism, theistic elements persist in many Buddhist traditions today, often in the form of devotional practices, rituals, and beliefs that resemble those found in theistic religions. Two prominent examples are Pure Land Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism, which illustrate how Buddhism can function with a decidedly “theistic” flavor in practice while still upholding non-theistic doctrine.

Pure Land Buddhism, widespread in East Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam), is explicitly built on faith in the saving grace of Amitābha (Amida) Buddha. In Pure Land thought, human beings in this corrupt age are incapable of achieving enlightenment on their own; the simplest and most effective path to salvation is reliance on Amitābha. Devotees repeatedly chant Amitābha’s name (the nembutsu) with sincere trust, aiming to be reborn in his Pure Land (Sukhāvatī). This practice bears a strong resemblance to devotional theism: Amitābha is regarded as a compassionate savior, listening to prayers and providing a paradise after death. Pure Land sutras describe Amitābha as having made vows to save all who call upon him, and he is often depicted enthroned in a heavenly realm, much like a benevolent god-king. What differentiates this from classical theism is that Amitābha is understood as a Buddha – an enlightened being who attained these qualities through eons of effort, not an eternally existing creator. He does not judge or demand worship; instead, he offers unconditional compassion. Still, for the lay follower, the experience of faith in Amitābha is analogous to faith in a deity. Scholars sometimes call Pure Land Buddhism “other-power” Buddhism (Tariki), in contrast to the “self-power” (Jiriki) of Zen or Theravāda. The popularity of Pure Land across East Asia testifies to a persistent human wish for divine succor and a personal relationship with the sacred. In practice, millions of Buddhists find spiritual fulfillment in praying to Amitābha or chanting his name, expecting his merciful intervention at the time of death. Thus, Pure Land Buddhism has preserved a significant theistic element within the Buddhist fold. Notably, even within this tradition, teachers remind followers that Amitābha is not a creator god or a punitive judge – his role is purely salvific and supportive.

Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayāna) provides another rich array of seemingly theistic elements. The Tibetan pantheon is teeming with deities – peaceful and wrathful – including Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, tantric gods and goddesses, protectors, and local spirits. Rituals in Tibet often involve invoking these beings, making offerings to them, and asking for their blessings or protection. The practice of Deity Yoga (mentioned earlier) entails visualizing oneself as a particular yidam (tutelary deity) such as Chenrezig (Avalokiteśvara) or Tara, which on the surface looks like devotional worship of a god or goddess. Monasteries in Tibetan regions are filled with icons of these deities, and laypeople regularly pray and make prostrations to them. In addition, the institution of the Dalai Lama and incarnate lamas in Tibetan Buddhism adds an almost theocratic element – the Dalai Lamas were both spiritual and temporal leaders believed to be emanations of Bodhisattvas. All these features can appear highly theistic. However, Tibetan Buddhism frames them within an esoteric understanding: the deities are manifestations of enlightened qualities and ultimately empty. For example, the goddess Tara is compassion in female form; worshipping her is a means to connect with and cultivate compassion. The fierce protector deities are seen as subjugated forces turned toward protecting the Dharma. Importantly, prayer in Tibetan Buddhism is often combined with the understanding that the real “response” comes from one’s own mind once it aligns with the enlightened realm of the deities. Nonetheless, in day-to-day life, Tibetan Buddhists certainly relate to these figures as powerful beings who can help or hinder, which is functionally similar to polytheism. It’s common for a Tibetan Buddhist to pray to Medicine Buddha for health, to Mahākāla for removing obstacles, or to local mountain gods for good weather. Such practices underscore that Buddhism as lived religion can accommodate a polytheistic cosmology where devotion and propitiation are meaningful.

Apart from Pure Land and Vajrayāna, other regional Buddhisms also retain theistic traces. In Theravāda Buddhist countries (Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos), the official doctrine is strictly non-theistic, yet folk practices integrate spirits and deities. For instance, Thai Buddhism incorporates the worship of local spirits (phi) and Hindu gods like Brahmā and Indra (known as Phra Phrom and Indra in Thai) as protectors of Buddhism. It is not unusual to see Thai people offer incense to a four-faced Brahmā statue (as at the famous Erawan Shrine in Bangkok) while on their way to a Buddhist temple. The Theravāda view rationalizes this by classifying such beings as “devas” who, though powerful, are themselves followers of the Buddha or guardians of his teaching. A Theravāda chronicle might recount how Sakka (Indra) attends the Buddha or how Upulvan (Vishnu) was entrusted to protect Sri Lanka – stories that give these gods a respected place, albeit subordinate to the Buddha’s Dharma. Additionally, throughout Southeast Asia, it is recognized that local spirit cults coexist with Buddhism: people appease village spirits or nature deities to ensure good fortune. An encyclopedia entry on Southeast Asian folk religion notes that Theravāda Buddhism “combines elements of local spirit religions, local versions of Brahmanism, and Buddhism” in a complex system. While Buddhist doctrine opposes reliance on spirits (since they are worldly and cannot bestow liberation), it does not deny their existence. Instead, interaction with certain deities (identified with Brahmanical gods or deified heroes) is considered meritorious and “wholesome,” as these gods are viewed as protectors of the faith. Thus, even in ostensibly atheistic Theravāda, there’s a tacit allowance for theistic behavior: monks might chant blessings to invoke deva protection, and laypeople routinely engage in practices that mirror theistic worship, though they conceptually understand that final refuge is taken only in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha (the Three Jewels).

In Japan, besides Pure Land, traditions like Shingon Buddhism present another interesting case. Shingon (an esoteric school) reveres Mahāvairocana Buddha as the cosmic principle, using elaborate rituals and mandalas that depict a divine Buddha realm encompassing hosts of deities. In Shingon, the line between Buddha and God can blur – Mahāvairocana is essentially identified with the Dharma-body of the Buddha, an ultimate reality that is omnipresent. Some scholars, as noted earlier, have likened this view to pantheism. At the popular level, Japanese Buddhism often blended with Shintō (the indigenous belief in kami spirits). Many Japanese Buddhists historically prayed to Buddhas and kami interchangeably for benefits. Figures like Kannon (Avalokiteśvara) became objects of heartfelt devotion, as a merciful divine mother figure. In fact, Zen Buddhism – known for its austere, self-reliant practice – even has a devotional side in East Asia, where images of Bodhisattvas and ceremonies for them are commonplace. This illustrates that devotion and theistic elements were never fully excised from Buddhism; rather, they were reinterpreted and given a new context.

In all these contemporary forms, theistic elements serve important social and spiritual functions. They provide a way for communities to express reverence, gratitude, and hope. For many Buddhists, it is psychologically meaningful to be able to pray for help – whether to Amitābha, Guan Yin, or a local deity – especially in times of distress. These practices knit Buddhism into the cultural fabric and make it accessible to all layers of society, not just those inclined to meditation or study. The key difference from outright theism is that within Buddhism’s doctrinal framework, these gods and Buddhas are not creators of the universe nor the ultimate goal; they are helpers, exemplars, or symbolic embodiments. The ultimate goal remains Nirvana or Buddhahood, a state which is achieved through understanding reality, not by the favor of a god.

In summary, contemporary Buddhism displays a spectrum: on one end, we have very non-theistic interpretations (e.g. secular Buddhism or certain Zen lineages focusing solely on meditation and insight with no reliance on supernatural aid), and on the other end, we have forms that are practically theistic (e.g. Pure Land services that resemble church services, with hymns to Amitābha’s grace). Tibetan Buddhism might even appear polytheistic to an outsider. Yet, these varied expressions all identify as Buddhist and share the same foundational teachings. This coexistence of atheistic philosophy with theistic practices is not seen as contradictory by practitioners; it is understood in terms of different levels of teaching for different needs (what Buddhism calls “skillful means” or upāya). The survival of theistic elements in Buddhism illustrates the religion’s flexibility and its deep insight into human nature: it provides intellectual rigor and transcendental insight for those who seek it, and devotional warmth and community rites for those who need it – often, the same person partakes of both at different times.

Epilogue: Implications for Religion and Metaphysics

The evolution of Buddhism from a context of theism to a consciously atheistic (or non-theistic) philosophy offers rich implications for how we understand religion and metaphysics. It challenges the common assumption that religion by definition requires belief in a God. Buddhism shows that a complete religious system – with ethics, rituals, cosmology, soteriology, and community – can flourish without a creator deity. This broadens our definition of religion: at its core, religion may be less about gods and more about addressing the fundamental human condition (suffering, meaning, morality) through an appeal to transcendent values or truths. In Buddhism’s case, the transcendent truth is Dharma and Nirvana, not a divine personality. The fact that millions have found existential fulfillment in Buddhism suggests that metaphysical comfort and ethical guidance can arise from understanding natural law and consciousness, rather than from divine commandments.

Buddhism’s journey also illustrates the dynamic interplay between philosophical clarity and human religiosity. On the one hand, Buddhism distilled a philosophy of emptiness and impermanence that undercuts any eternal being or essence – a standpoint some consider profoundly liberating and even scientific in spirit. On the other hand, as we explored, Buddhism incorporated or reintroduced theistic-like elements to meet devotional needs. This reveals an important truth about metaphysics in practice: abstract philosophy alone does not satisfy the whole of human nature. People yearn for relationship, narrative, and symbols. Buddhism adapted by transmuting gods into aspects of its metaphysics – turning devas into Dharma protectors, turning the Buddha into a cosmic principle, etc. The implication is that metaphysics and myth can coexist and even enrich each other. A religion can maintain a rigorous metaphysical view (such as no independent self or creator) while employing mythical language and imagery as pedagogical tools. This calls into question a strict dichotomy between rationality and religiosity; Buddhism exemplifies a tradition where rational insight (wisdom) and devotional practice (faith) are both cultivated, aimed at the same ultimate goal.

From a theological perspective, Buddhism’s evolution urges theologians of other faiths to ponder concepts of God in more subtle ways. Buddhism effectively replaced God with Dharma – a law without a lawgiver. Yet, in Mahāyāna, something like grace re-enters (through Buddhas’ compassion). It is as if Buddhism eliminated the ontological God (creator, prime mover) but retained a sense of the functional God through the principles of compassion and wisdom operating in the universe. The metaphysical implication is that what people seek from “God” – love, salvation, justice – might be attainable through impersonal or distributed processes (karma, community, personal cultivation) rather than a single supernatural will. This resonates with modern views that emphasize process and interconnection over static being. Indeed, some comparative religion scholars have drawn parallels between Buddhist ideas of interdependent emergence and process theology in Christianity, suggesting future dialogues where God is reconceived less as a separate being and more as the ground of interconnected being (an idea some mystics and process theologians advocate). Buddhism’s example thus pushes the envelope on how flexible the concept of the divine can be – perhaps pointing toward a convergence where theism and non-theism meet in a shared appreciation of an ultimate reality that is at once empty of self and full of compassion.

On the level of individual spirituality, the Buddhist case has an existential implication: it asserts that meaning and morality do not require a God. The path to liberation is an inner transformation – any divine figure is essentially a mirror or aid for that inner work, not a judge or creator. This empowers the individual and also removes the problem of theodicy (justifying God in the face of suffering): suffering is explained by impersonal causes, which though daunting (because responsibility falls on us), is also hopeful (because change is possible through our actions). The absence of a creator also means an absence of a fixed creation – reality is continuously created by our deeds and mental states. This offers a profoundly dynamic metaphysic: reality is not a finished product given by a divine fiat, but a fluid, co-arising process. In an age where science depicts an evolving cosmos and complex systems, Buddhism’s non-theistic metaphysics resonates strongly, suggesting a form of spirituality well-suited to a scientific worldview.

Finally, Buddhism’s evolution illustrates the resilience and adaptability of truth. Stripped of the need to anchor itself in an ultimate being, Buddhism anchored itself in an ultimate experience – enlightenment. This shift from devotion to doctrine, and back to devotion in new form, shows that religions can cycle through phases of demythologizing and remythologizing. Buddhism demythologized Indian religion by removing Brahmā as creator; then it remythologized its own truth with myriad Buddhas and Bodhisattvas when needed. The implication is that in the pursuit of the ineffable, humanity will always oscillate between the One and the Many, the Formless and the Formed. Buddhism found a unique balance: its heart is atheistic in content but religious in form. It invites us to consider that perhaps the highest “God” is not a being at all, but Being-as-such – the suchness (tathatā) of reality, which requires no creator.

In conclusion, the story of Buddhism’s shift from theism to atheism (or more precisely, from engaging theism to transcending it) is a testament to the diversity of religious expression. It shows that a great religious civilization can thrive without a central god figure, and yet not lose any of the depth, ethics, or awe that we associate with religion. For metaphysics, it underlines an insight: ultimate reality might be better approached through principles and inner realization than through personification – or, as Buddhism would say, through direct insight into emptiness and compassion rather than through clinging to any concept of “God.” In a world where interfaith understanding is increasingly important, Buddhism’s example offers a bridge: it has something in common with atheistic humanism (in rejecting divine authority) and something in common with devotional religion (in fostering reverence and faith, albeit redirected toward non-theistic targets). It thus broadens our appreciation of how humans relate to the sacred, reminding us that the sacred need not always wear the face of a deity – it can also be found in the silent, luminous truth discovered within.

Sources:

- Skilton, Andrew. “Buddhism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Atheism (2015). ****

- Existential Buddhist (Segall, S.Z.). “Is Buddhism Non-theistic?” (2011). ****

- Pāli Canon – e.g., Dīgha Nikāya, Brahmajāla Sutta & Tevijja Sutta; Saṃyutta Nikāya 15:1-2; Majjhima Nikāya 49 (Brahma-nimantanika Sutta). ****

- Richard Hayes (Buddhist scholar), on early Buddhist views of a creator. ****

- Narada Thera, on Buddha’s critique of creationism (Anguttara Nikāya). ****

- Peter Harvey, “Buddhism and Monotheism” (2019), on absence of a creator in Buddhism. ****

- Britannica & Oxford Reference on Buddhism’s spread and sects (various).

- Encyclopedia.com (Folk Religion, Southeast Asia), on syncretism of Buddhism with local deities. ****

- Wright, Dale S., The Six Perfections (on Mahayana devotionalism and philosophy).

- Paul Williams, Mahayana Buddhism (on the concept of eternal Buddhas). ****

- Cabezón, José I., on Buddhist cosmology vs. creator God. ****

- Buddhaghosa, Visuddhimagga (5th c.), quote denying creator. ****

- Dharmakīrti’s Pramāṇavārtika and Ratnakīrti’s Īśvara refutation (arguments against God). ****

- Śāntideva, Bodhicaryāvatāra (8th c.), ch.9 – arguments versus Īśvara (implied by Skilton’s analysis).

- Michael D. Nichols, on the Brahma Baka story indicating belief in a creator is a trick of Māra. ****

- Guang Xing, The Concept of the Buddha – describing Mahayana Buddha’s attributes. ****

- Douglas Duckworth, on comparisons to pantheism in Buddhist thought. ****

Leave a comment