Epigraph:

Such is Allah, your Lord. There is no God but He, the Creator of all things, so worship Him. And He is Guardian over everything.

Eyes cannot reach Him but He reaches the eyes. And He is the Incomprehensible, the All-Aware. (Al Quran 6:102-103)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD

The Experiment That Defied Expectations

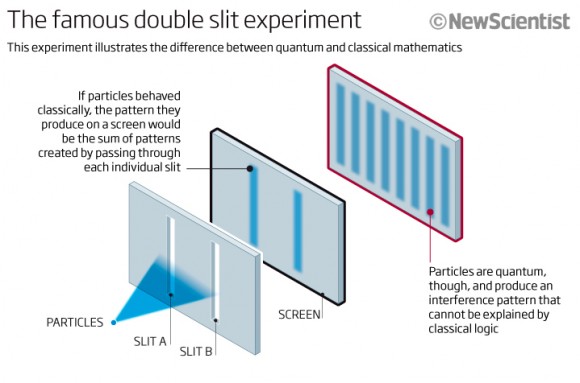

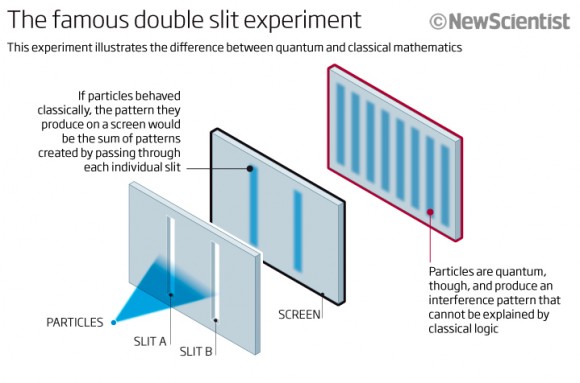

In a darkened room over two centuries ago, an English scientist named Thomas Young conducted a simple yet profound experiment. He shone light through a thin card pierced by two parallel slits and observed the pattern that formed on a screen behind it. Instead of two bright spots corresponding to the slits (as one would expect if light were made of particles like Newton’s “corpuscles”), Young saw a series of alternating bright and dark fringes – an interference pattern. It was as if the light waves emerging from the two slits were overlapping, creating regions of enhancement (bright bands) and cancellation (dark bands). This was striking evidence that light behaves like a wave, since only waves interfere in this manner. Young’s double-slit experiment of 1801 vindicated the wave theory of light championed by Christiaan Huygens, and showed Newton’s particle view to be incomplete. The discovery was presented in a story-like fashion to the Royal Society, and it must have felt like a magic trick at the time – adding a second slit caused some light on the screen to disappear into darkness! How could letting more light through ever result in less light in some places? The answer: through wave interference, where peaks and troughs cancel out. Young’s insight was a triumph of classical physics, illuminating (literally) the wave nature of light and marking a turning point in our understanding of nature.

Unbeknownst to Young, however, his experiment held an even deeper mystery that would only come to light a century later. The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought revelations that light can also act like particles (photons) – as evidenced by Einstein’s explanation of the photoelectric effect – and conversely, that matter can act like waves. In 1927, Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer (and independently George Thomson) demonstrated that electrons (supposedly “particles” of matter) produce interference patterns just like light does en.wikipedia.org. This was astonishing: electrons fired at a double slit formed the same kind of striped pattern on a screen as light waves do. In other words, the old wave-particle divide had blurred. Tiny bits of matter behaved like rippling waves. All of a sudden Young’s experiment wasn’t just about optics or light – it was probing the heart of quantum mechanics and what physicist Niels Bohr would call wave-particle duality.

Bohr’s principle of complementarity would soon formalize this mind-bending idea: quantum entities have both wave and particle aspects, but you can only observe one aspect at a time, depending on how you set up your experiment. The double-slit setup perfectly encapsulates this duality. When we don’t try to peek at which slit a particle (like an electron or photon) goes through, it behaves like a wave – going through both slits at once in a sense, and producing an interference pattern of many bands on the screen. But if we observe or obtain information about which slit it passes, it behaves like a particle – going through one slit or the other, and the interference fringes vanish, leaving just two fuzzy patches behind the slits. Bohr stressed that these two modes of behavior are mutually exclusive yet complementary – you cannot see the wave and particle nature simultaneously. “The path comes into existence only when we observe it,” as Werner Heisenberg succinctly put it.

Read further in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment