Presented by Zia H Shah MD with help of ChatGPT

Introduction

Science operates under a guiding principle that distinguishes how we investigate nature from what we may ultimately believe about reality. In modern scientific practice, researchers adopt methodological naturalism – they seek explanations in terms of natural causes and laws and refrain from invoking supernatural agents in their experiments and theories. By contrast, metaphysical naturalism is a broad philosophical stance or worldview asserting that nature is all that exists, denying the reality of any supernatural realm en.wikipedia.org. The distinction between these two forms of naturalism is crucial in discussions at the intersection of science, philosophy, and theology. This article will compare and contrast methodological and metaphysical naturalism, drawing on perspectives from the philosophy of science, theology, and epistemology. We will trace their historical development, clarify definitions, examine philosophical implications, and highlight their respective roles in scientific practice. Prominent thinkers – including biologist Richard Dawkins, philosopher Alvin Plantinga, philosopher of science Karl Popper, and paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould – have weighed in on this subject. By engaging their insights and examples, we will support methodological naturalism as a foundational principle of scientific inquiry while treating metaphysical naturalism as a debatable metaphysical position on which theists and atheists can reasonably disagree. Ultimately, we affirm the importance of maintaining methodological naturalism in science, even as we recognize the diverse philosophical views about the metaphysical scope of nature.

Definitions

Methodological Naturalism (MN): In simplest terms, methodological naturalism is the operating rule that science restricts itself to natural causes and explanations. It is a methodological commitment rather than an all-encompassing claim about reality. Under MN, scientists assume that for any phenomenon under study, there are natural mechanisms that can be observed, tested, and understood – even if those mechanisms are not yet known damienmarieathope.com. This approach “says nothing about God’s existence” en.wikipedia.org; it does not deny or affirm the supernatural, but simply sets such considerations aside. As the National Academy of Sciences has put it, science by definition is limited to explaining the natural world through natural processes, and therefore cannot invoke supernatural causation (because supernatural causes, by definition, lie outside empirical inquiry). Biologist Stephen Jay Gould succinctly captures this limit: “Science can work only with naturalistic explanations; it can neither affirm nor deny other types of actors (like God) in other spheres.” afterall.net In other words, methodological naturalism is an epistemological stance about what kinds of hypotheses are testable and scientifically fruitful. It is “a cornerstone of science,” embraced by both scientists and philosophers, as it directs researchers to seek answers that can be quantified, measured, and tested damienmarieathope.com. Importantly, MN is heuristic and self-limited: it does not presume that nature is all that exists, only that science, as a method, deals with natural phenomena. As philosopher of science Robert T. Pennock explains, science is not based on “dogmatic ontological or metaphysical naturalism,” but rather “makes use of naturalism only in a heuristic, methodological manner.” discourse.peacefulscience.org

Metaphysical Naturalism (MetN): Metaphysical naturalism (also called ontological or philosophical naturalism) is a worldview or doctrine about the fundamental nature of reality. In contrast to MN’s neutrality on ultimate questions, metaphysical naturalism asserts that nature is all there is – there exist no supernatural beings, forces, or realms beyond the natural universe en.wikipedia.org damienmarieathope.com. A classic encapsulation comes from cosmologist Carl Sagan: “The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be.”en.wikipedia.org In other words, MetN flatly rejects the existence of the supernaturalen.wikipedia.org. This view entails that everything from the origin of the universe to the emergence of life and consciousness must ultimately be explainable by the same kinds of natural principles studied in science. Metaphysical naturalism is thus an ontological commitment – a claim about what exists. It is often associated with materialism or physicalism (the idea that only matter/energy exist). Philosopher Arthur Danto describes this kind of naturalism as a form of philosophical monism holding that “whatever exists or happens is natural in the sense of being susceptible to explanation through methods which, although exemplified in the natural sciences, are continuous across all domains… repudiating the view that there could exist any entities beyond the scope of scientific explanation.”en.wikipedia.org. In short, metaphysical naturalism says there is nothing beyond nature, and hence no miracles, spirits, or deities are realen.wikipedia.org. It is a comprehensive belief about the universe – a metaphysical position that one may accept or dispute.

It should be clear that methodological and metaphysical naturalism operate at different levels. One is a constrained method for inquiring about the world, and the other is a sweeping claim about the ultimate reality of the worldplato.stanford.edu. As we will explore, confusion between the two has led to significant debates in science, philosophy, and theology. For example, biologist Eugenie Scott emphasizes that failure to distinguish them is an error: “Science as practiced today is methodologically naturalistic: it explains the natural world using only natural causes… There is also an independent sort of naturalism, philosophical naturalism, a belief… that the universe consists only of matter and energy and that there are no supernatural beings… Johnson’s crucial error is not distinguishing between these two kinds of naturalism.”damienmarieathope.comdamienmarieathope.com. With these definitions in hand, we can now turn to how these ideas developed historically and how they feature in contemporary discourse.

Historical Background

The impulse to seek natural explanations has deep historical roots. In ancient Greece, thinkers like Thales of Miletus (6th century BCE) can be seen as early exemplars of a methodological naturalist approach. Thales famously proposed that earthquakes were not the wrath of sea-god Poseidon but had natural causes (he suggested the Earth floats on water and is rocked by waves) – an extraordinary attempt to explain a phenomenon without recourse to mythologydiscourse.peacefulscience.org. Throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, many scholars still invoked divine action for various phenomena, yet the idea of searching for regularities in nature persisted. The scientific revolution (16th–17th centuries) dramatically solidified methodological naturalism as scientists like Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton sought mathematical laws and mechanistic causes for motion, astronomy, and physics. Even though these early scientists were often personally religious, in their scientific work they strove to explain observations via natural law (Newton, for instance, described gravity governing planetary orbits rather than attributing planetary motion to angels). This trend reflected a growing consensus that science progresses by examining natural causes, with any reference to God’s direct intervention treated as beyond the scope of scientific analysis.

By the 19th century, methodological naturalism had become a standard operating procedure in emerging fields such as geology and biology. Geologists like Charles Lyell championed “uniformitarianism” – the idea that only ordinary natural processes (e.g. erosion, sedimentation), operating over long periods, should be used to explain Earth’s features, explicitly arguing against catastrophic supernatural events as scientific explanations. The culmination of this naturalistic approach was Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection (1859), which provided a profoundly successful natural explanation for the diversity of life. Darwin’s work struck a powerful blow to the notion that biological complexity required supernatural design. As Richard Dawkins later observed, “Darwin made it possible to be an intellectually fulfilled atheist.”libquotes.com. Dawkins’ remark highlights how a scientific method limited to natural causes (Darwin never invokes God in explaining the origin of species) influenced broader worldviews: once nature could “do the creating” via evolutionary processes, one could reject metaphysical naturalism’s chief rival (theism) with greater confidence. In other words, Darwin’s achievement exemplified how sticking to methodological naturalism in science – explaining life through unguided natural mechanisms – indirectly supported a metaphysical naturalist outlook for those, like Dawkins, inclined toward atheism. (It is important to note, however, that Darwinism’s success does not logically entail metaphysical naturalism – more on that in the comparative analysis.)

During the 20th century, philosophers of science explicitly reflected on science’s naturalistic methods. Karl Popper, for example, in the mid-1900s emphasized that science should proceed by bold conjectures and empirical refutation (falsifiability) and cannot accommodate unfalsifiable explanations. While Popper’s focus was on induction and demarcation rather than “naturalism” per se, his views implied that appeals to supernatural causes have no place in science because such appeals typically cannot be tested or potentially falsifieden.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Many other thinkers affirmed that limiting science to natural explanations was not a capricious bias but a practical necessity: only by searching for natural causes could science yield knowledge that is testable and cumulative. By mid-century, metaphysical naturalism also gained prominence in intellectual circles (e.g. among American pragmatists and analytical philosophers), but often as a separate philosophical commitment rather than a required premise for doing scienceplato.stanford.eduplato.stanford.edu.

Interestingly, the term “methodological naturalism” itself entered the philosophy of science lexicon relatively late. Historian Ronald Numbers notes that philosopher Paul de Vries coined the term around 1983, explicitly to distinguish the pragmatic method of science from ontological or metaphysical claimsen.wikipedia.org. (An earlier use of the phrase in 1937 by Edgar Brightman is documented, but it did not develop the distinction fullyen.wikipedia.org.) De Vries’ formulation came as debates over evolution and creationism were intensifying: it became increasingly important to clarify that accepting evolution (or doing any science) does not require one to profess atheism or deny God’s existence, because science’s naturalism is about method, not metaphysics. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, this distinction took center stage in courtrooms and classrooms. For example, Phillip Johnson – a leader of the Intelligent Design (ID) movement – attacked evolutionary theory as based on an assumption of philosophical naturalism, arguing that this was a covert religious (atheistic) doctrine. In fact, Johnson conflated the two forms of naturalism: he claimed science’s methodological naturalism was essentially the same as metaphysical naturalism, and thus that teaching evolution promoted atheismdamienmarieathope.comdamienmarieathope.com. In response, scientists and philosophers (many of them religious believers themselves) pushed back, underscoring the difference. Biologist Kenneth Miller and geneticist Francis Collins, both devout Christians, were vocal in asserting that one can practice methodological naturalism in science and still reject metaphysical naturalism in personal beliefrationalwiki.org. Philosopher Robert T. Pennock and anthropologist Eugenie Scott likewise stressed in the 1990s that evolution as science makes no theological claims – it merely uses the naturalistic method common to all sciencedamienmarieathope.comdamienmarieathope.com. This clarification played a role in the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover trial, where a U.S. federal court ruled that Intelligent Design was not science partly because it violated methodological naturalism (by positing an unevolvable “designed” biological feature). By this point, methodological naturalism had become an explicit, well-defended norm in scientific methodology, whereas metaphysical naturalism remained a separate philosophical stance that scientists as individuals might either accept or reject.

Comparative Analysis: Scope and Commitments

Having defined the terms and surveyed their development, we turn to a direct comparison of methodological vs. metaphysical naturalism. Despite sharing the word “naturalism,” they differ in scope, purpose, and epistemic commitmentplato.stanford.edu. Below we analyze these differences and their implications, highlighting examples that show how one can adhere to methodological naturalism (MN) in science without subscribing to metaphysical naturalism (MetN) – and vice versa.

- Domain and Scope: Methodological naturalism is narrowly scoped to the practice of science and knowledge-gathering. It addresses how we investigate questions about the world. Metaphysical naturalism is sweeping in scope, addressing what exists in the entirety of reality. MN says: “We will study phenomena as if only natural processes are at work,” whereas MetN says: “In fact, only natural processes and entities exist.” The former is a conditional, methodological rule, the latter an unconditional ontological claim. An important consequence is that MN is compatible with a range of personal worldviews (a scientist can adopt MN in the lab, yet personally believe in God or the supernatural in other contexts), while MetN, by definition, is not compatible with traditional theism or any belief in the supernatural.

- Epistemic Commitments: Methodological naturalism is effectively an epistemological stance about what constitutes a reliable explanation. It reflects humility about what can be known or tested: if a cause is not natural, science simply has no tool to verify it. Thus, MN imposes a practical limit – it commits us to seeking natural explanations that can be empirically scrutinized. Metaphysical naturalism goes further, making a truth claim: it commits to the belief that nothing lies outside the natural order. This is a strong epistemic claim about reality: namely, that all truths are ultimately scientific truths (or at least natural truths) and anything not accessible to science does not exist. Critics often point out that this claim, by itself, is not empirically provable – it is a philosophical inference or presupposition. Indeed, Alvin Plantinga and other philosophers argue that metaphysical naturalism functions almost like a belief system in its own right, providing naturalistic answers to deep existential questions in the way religions provide supernatural answersen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Plantinga notes that naturalism, when conjoined with evolution, must even tackle self-referential epistemological problems (his infamous “evolutionary argument against naturalism” contends that a purely naturalistic evolution undermines confidence in our cognitive faculties)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org. Methodological naturalism, on the other hand, carries no such burdens – it does not assert that only natural causes exist, only that we limit ourselves to natural causes when doing science. In practice, this means MN is often seen as a provisional strategy or rule of thumb that has proven extraordinarily fruitful, rather than a dogmatic pronouncement about reality.

- Necessity in Science vs. Debatability in Philosophy: Perhaps the most salient difference is that methodological naturalism is considered indispensable in science, whereas metaphysical naturalism is a matter of philosophical debate. The track record of science demonstrates why MN is held to be indispensable: by consistently looking for natural causes, scientists have mapped the genome, cured diseases, and sent humans to the Moon. None of these achievements required invoking supernatural intervention; in fact, assuming natural causes were at work was precisely what made these endeavors possible. Metaphysical naturalism, however, is not at all “necessary” for doing science – it is entirely possible to conduct first-rate scientific research while personally believing in God or other supernatural entities. History provides ample examples: the 20th-century geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky was a devout Eastern Orthodox Christian;Arthur Eddington, who confirmed Einstein’s relativity, was a Quaker; and today one finds many religious scientists in fields from cosmology to chemistry. All of them practice methodological naturalism in their scientific work (they seek natural explanations for the phenomena they study) while rejecting metaphysical naturalism in their broader worldview. As Stephen Jay Gould highlighted with concrete examples, “Either half my colleagues are enormously stupid, or else the science of Darwinism is fully compatible with conventional religious beliefs — and equally compatible with atheism.”afterall.net. Gould’s point is that the same scientific method and theories (e.g. evolutionary biology) are embraced by scientists who are theists and by those who are atheists, which proves that acceptance of scientific, naturalistic methodology does not hinge on one’s metaphysical stance. On the flip side, one could in principle be a metaphysical naturalist and yet support research into, say, parapsychology or other fringe topics that mainstream scientists might consider dubious – but even those attempts, to gain scientific credibility, would have to use methodological naturalism (i.e. test claims with naturalistic assumptions).

- Relationship Between the Two: A key analytical question is whether methodological naturalism implies, supports, or biases one toward metaphysical naturalism. Can one hold MN without MetN, and vice versa? In practice, yes. A theistic scientist is a clear case of MN without MetN: they assume only natural causes in the lab but believe in a supernatural realm in their personal faith. They might say, for instance, that God usually works through natural laws (which science studies) but could also act beyond them – however, such extraordinary acts, if they occur, lie outside science’s purview. Conversely, a person could espouse MetN (believe only nature exists) yet recognize MN as just the method of science and not the reason they reject the supernatural. Such a person might argue that even outside of science, they find no credible evidence for the supernatural; their adherence to MetN is a philosophical conclusion rather than a direct requirement of doing science. Philosopher David Papineau observes that “the great majority of contemporary philosophers would happily accept naturalism [in rejecting supernatural entities and trusting science as a route to truth]”en.wikipedia.org, but this consensus on a naturalist worldview extends well beyond what scientific methodology alone can dictate. Methodological naturalism does not logically entail metaphysical naturalism, but historically, the success of MN in explaining more and more has encouraged many to adopt MetN. In other words, the more the naturalistic approach succeeds in science, the more plausible the naturalistic worldview may appear to some. Dawkins and other New Atheist thinkers frequently make this move: because science has explained so much without God, they infer that no supernatural reality is needed at all. However, that leap from method to metaphysics is philosophically contested. As a counterpoint, theists like Plantinga argue that excluding the supernatural a priori (even just methodologically) might sometimes blind science to truth if, in rare cases, a supernatural explanation were the correct one. For instance, if one believes that God could act in nature (perform a miracle), then a strict methodological naturalism would prevent a scientist from recognizing that miracle as such – they would be forced to seek a natural explanation and perhaps never find a satisfactory one. This remains a hypothetical scenario, as thus far methodological naturalism has been spectacularly successful; but it underlines that the divide between MN and MetN is often philosophically charged. As philosopher Alvin Plantinga put it, proponents of science’s naturalistic methodology often claim it keeps science “religiously neutral,” but he contends that in practice science can intersect with religious claims and that “the actual practice and content of science” sometimes challenges the supposed neutralityphilpapers.org. Plantinga’s critique has fueled debate on whether MN is a mere policy or if it carries implicit metaphysical baggage. Most scientists respond that MN as practiced does not presume atheism – it only brackets questions of supernatural causation as out of scope for scientific inquiry. In summary, while MN and MetN can be philosophically entangled, they are logically distinct: one can accept the methodology without the metaphysics, and doing so is indeed common among scientists.

Implications for Science and Religion

The distinction between methodological and metaphysical naturalism has significant implications for the dialogue (and sometimes conflict) between science and religion. Keeping the two naturalisms separate can serve as a buffer that allows robust scientific inquiry to coexist with diverse religious beliefs. Methodological naturalism, as a ground rule of science, has a unifying effect: it doesn’t matter whether a scientist is Christian, atheist, Muslim or Hindu – when doing science, they all follow the same empirical protocols and look for natural causes. In this sense, MN is often portrayed as a neutral stance with respect to religion. Stephen Jay Gould advocated this view in his principle of Non-Overlapping Magisteria (NOMA): science and religion occupy separate domains (magisteria), where science covers the empirical realm of “nature’s factuality” and religion covers questions of meaning and morality. “Science simply cannot adjudicate the issue of God’s possible superintendence of nature. We neither affirm nor deny it; we simply can’t comment on it as scientists.” Gould wrote, adding that Darwinian science is “fully compatible with conventional religious beliefs – and equally compatible with atheism”afterall.netafterall.net. In other words, if science sticks to methodological naturalism, it avoids treading on religious territory: it will not claim that God does or doesn’t exist, it will only say that we can explain phenomena without invoking God. This perspective tends to reduce conflict, implying that a scientist can be religious without any contradiction, as long as they do not expect scientific research to validate supernatural claims.

On the other hand, when metaphysical naturalism is asserted in the name of science, it does generate conflict with religion. Strong advocates of metaphysical naturalism (often also vocal atheists) sometimes present the success of science as positive evidence that the supernatural is an illusion. Richard Dawkins, for instance, has argued that the real battle is “between naturalism and supernaturalism”, framing acceptance of evolutionary science and a naturalist worldview as opposing religious beliefmetanexus.net. In his book The God Delusion, Dawkins does not hide that he sees science’s naturalistic framework as inherently at odds with theism, and he famously attacks “anything and everything supernatural” as unsupported and unnecessarymetanexus.net. Such rhetoric blurs the line between methodological and metaphysical commitments, effectively using science’s methodological filter as if it were a metaphysical conclusion. The implication for religion in this stance is stark: if one accepts the Dawkins-style view, modern science doesn’t just methodologically exclude God – it concludes God is absent. Not surprisingly, this draws fire from religious thinkers. They argue that metaphysical naturalism masquerading as scientific reasoning oversteps what science can legitimately say. For example, theists often point out that saying “science finds no evidence of God” is not the same as “science has proven there is no God” – the former is a statement about method and available evidence (consistent with methodological naturalism), while the latter is a sweeping metaphysical claim that goes beyond empirical science.

Within theology and philosophy of religion, there have been a range of responses to science’s methodological naturalism. Many theologians fully accept MN as a sensible delimitation of science’s scope. They may argue that God, if God exists, typically works through natural processes (providing consistent order in nature), and thus science is the study of God’s ordinary way of operating – miracles, if they occur, are by nature rare and not predictable, so they lie outside science’s competency. This view allows religious believers to embrace all the findings of methodologically naturalistic science (from the Big Bang to evolution) and simply interpret them within a broader metaphysical framework that includes God. Indeed, several prominent scientists who are people of faith (like geneticist Francis Collins) have testified that understanding the natural mechanisms of life does not diminish their belief in a divine creator; they see scientific discovery as “thinking God’s thoughts after him” in a metaphorical sense. In this accommodationist perspective, methodological naturalism poses no threat to religion – it is just the correct way to do science, and metaphysical naturalism is rejected as an unwarranted extrapolation. Alvin Plantinga, while critical of the insistence on MN in all contexts, concedes that doing science with naturalistic assumptions is not automatically atheistic. He notes that “science is said to be religiously neutral, if only because science and religion are, by their very natures, epistemically distinct”philpapers.org – meaning that as long as one keeps science in its lane, it makes no pronouncements on God. In line with this, one can find theistic philosophers (e.g. Del Ratzsch, John Polkinghorne) who explicitly endorse MN for scientific work and argue that problems only arise when scientists or atheists conflate it with a metaphysical commitment.

However, there is also a strain of thought in theology that questions whether methodological naturalism should be absolute. If one believes strongly that God’s action is observable in the world, one might ask: should scientists be allowed to consider supernatural explanations in extraordinary cases? Plantinga himself provocatively suggested that Christian scientists might adopt what he called an “Augustinian science” – open in principle to divine agency – if following strict MN would lead them to wrong conclusions (for instance, he imagines if evidence suggested that God’s miraculous action was part of natural history, scientists wedded to MN would miss it by assumption). So far, there have been no compelling scientific discoveries that unambiguously require abandoning MN, and attempts to introduce supernatural causation in science (such as Intelligent Design claims of “irreducible complexity” requiring an unnamed designer) have not met the standards of scientific evidence. The mainstream view (shared even by most religious scientists) is that departing from methodological naturalism would undermine science’s reliability. If researchers could invoke miracles whenever they reach a difficult gap in understanding, the rigorous progress of science would likely stall – why struggle to find a natural explanation if one could say “and then a miracle happened”? Thus, even many theists defend MN in science as a discipline of inquiry that, ironically, also protects the integrity of theological claims by not trivializing divine action as a gap-filler for scientific problems. They prefer to see God, if at all, in what science ultimately cannot explain (or in the mere existence of a natural order), rather than inserting God into the day-to-day empirical equations which science is solving. This aligns with the concept of “God’s two books” (nature and scripture) operating on different levels of explanation.

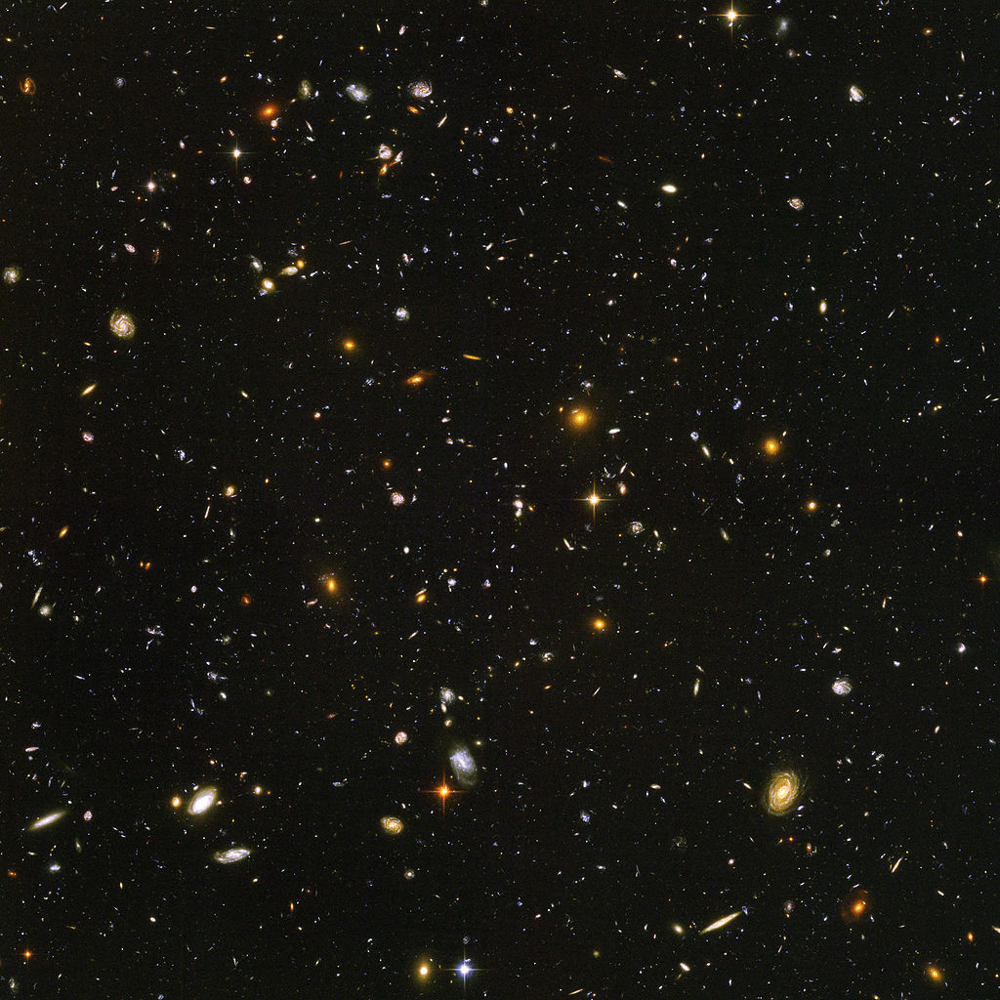

For its part, science benefits from methodological naturalism by staying focused on empirically solvable questions. The spectacular imagery from modern telescopes, such as the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field showing countless galaxies across billions of light-years, is a testament to how far the naturalistic paradigm has taken us in understanding the universe. By assuming that the same consistent physical laws apply everywhere, scientists were able to interpret such images and deduce the evolution of galaxies over cosmic time – endeavors that would be impossible if one assumed arbitrary supernatural interventions in different corners of the cosmos. In practical terms, MN has fostered a mindset of investigative perseverance: even when faced with phenomena that are not yet understood, scientists presume there is a natural explanation and keep searching (rather than attributing the mystery to inscrutable supernatural causes and giving up). This presumption has paid off repeatedly: lightning was once deemed an act of gods, now it’s explained by electrical discharge; diseases were “curses” or demonic possession, now we have the germ theory and modern medicine. Each time, the methodological naturalist approach led to tangible knowledge and often technological benefits.

At the same time, recognizing the philosophical diversity regarding metaphysical naturalism can improve science-religion dialogue. It helps to alleviate religious fears that science is inherently atheistic. As Eugenie Scott articulated in response to creationist claims: the fact that some scientists personally are philosophical naturalists (atheists) “does not make science atheistic any more than the existence of non-believing bookkeepers makes accounting atheistic.”damienmarieathope.com Science, as a method, simply does not take a stance on God; it only insists that any causes it does invoke be observable and testable. Maintaining this distinction publicly allows educators, for example, to teach evolutionary biology in schools while assuring students that the science curriculum is not a veiled attempt to proselytize atheism – it’s about evidence, not doctrine. Likewise, it permits religious communities to engage with scientific findings (like climate change or medical research) based on evidence, without feeling that accepting the science equates to renouncing their faith.

In summary, methodological naturalism functions as a pragmatic common ground – a lingua franca of investigation that does not prejudge metaphysical questions – whereas metaphysical naturalism remains a standpoint in the worldview conversation between secular and religious perspectives. As long as participants in that conversation acknowledge that science’s success does not automatically validate metaphysical naturalism, and that one can be a sincere scientist without embracing the naturalist worldview, there is room for a constructive relationship between science and religion. Conversely, if either side forgets the distinction (for instance, if scientists convey that “science has proved there is no soul” or if religious apologists insist that accepting evolution equals endorsing atheism), then misunderstandings and unnecessary conflict arise.

Conclusion

In closing, methodological naturalism and metaphysical naturalism must be understood as distinct yet often conflated concepts. Methodological naturalism is best viewed as a foundational principle of scientific inquiry – a disciplined commitment to seek natural explanations and to test hypotheses empirically. It has a proven track record as the engine of scientific discovery, precisely because it restricts science to questions that can be answered with evidence and reason. We have seen through historical examples and philosophical analysis that methodological naturalism is instrumental rather than ideological: it’s a technique, a strategy for advancing knowledge. By bracketing out supernatural explanations, scientists – regardless of personal belief – work with a common toolkit and can build on each other’s results, confident that the causes they invoke are accessible to all observers. To borrow the words of philosopher Robert Pennock, science “uses naturalism only in a methodological manner,” not as an absolute creeddiscourse.peacefulscience.org. This pragmatic constraint is, in a sense, the price of the success of science, and it is a price well worth paying for the reliable knowledge it yields.

Metaphysical naturalism, on the other hand, is a comprehensive metaphysical position about what ultimately exists. It ventures beyond the realm of testable hypotheses into the domain of philosophical interpretation. One can argue for or against metaphysical naturalism on various grounds – logical, moral, existential – and both atheists and theists have engaged in this debate for centuries. Crucially, the choice to endorse or reject metaphysical naturalism remains outside the competence of science itself. Science can certainly inform the discussion: the more phenomena we explain naturally, the less room there seems to some for anything beyond nature. But that inference is not itself a scientific result; it is a philosophical extrapolation. As such, reasonable people will continue to disagree on metaphysical naturalism. Some, like Dawkins, find the success of science a compelling reason to embrace the view that nothing transcends nature. Others, like Plantinga (and many religious scientists), maintain that there are realities science simply isn’t equipped to address – that methodological naturalism in science leaves open the possibility of a supernatural order which science, by design, is silent about. This debate is healthy and will likely persist as long as humans reflect on questions of meaning and origin.

What is vital – especially in education and public discourse – is to maintain the distinction between these two naturalisms. Doing so allows us to champion methodological naturalism as non-negotiable in the science classroom and laboratory, without forcing a metaphysical ideology onto those who participate in or benefit from science. It also allows religious and non-religious individuals to find common ground in supporting scientific research, understanding that accepting the methods of science does not require abandoning one’s metaphysical or theological framework. In a pluralistic society, this nuance is key: we can all agree that science should explain the natural world by looking to natural causes (because this approach works and has no viable substitute), while still amicably debating what the ultimate meaning of the natural world is, or whether there is something beyond it.

In conclusion, methodological naturalism stands as a pillar of scientific practice, underpinning the objectivity and success of the scientific enterprise. It ought to be strongly defended and preserved in the face of any who would dilute it – be it by allowing supernatural causation into science or by conflating science with an atheistic agenda. At the same time, we recognize that metaphysical naturalism is a worldview choice, not a requisite of doing science. A clear separation of these concepts enriches both science and philosophy: science remains robust, and the philosophical diversity regarding life’s ultimate questions is acknowledged rather than artificially resolved. By keeping methodological naturalism in its proper place, we ensure science remains a powerful, inclusive tool for understanding our world. And by treating metaphysical naturalism as a separate, debatable proposition, we foster an environment where science and a variety of metaphysical beliefs – from staunch naturalism to devout theism – can co-exist in constructive dialogue. Maintaining this balance is not only academically sound but culturally important, as it affirms that one can fully embrace science while also thoughtfully engaging with the enduring mysteries that lie beyond the scope of scientific method.

Additional reading

Atheist Philosophers and Scientists Possessed by Laplace’s Demon

Leave a reply to Agreeing and Disagreeing with Nidhal Guessoum and Pervez Hoodboy – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply