Epigraph:

He is the First and the Last, and the Manifest and the Hidden, and He knows all things full well. He it is Who created the heavens and the earth in six periods, then He settled Himself on the Throne. He knows what enters the earth and what comes out of it, and what comes down from heaven and what goes up into it. And He is with you wheresoever you may be. And Allah sees all that you do. (Al Quran 57:3-4)

Written and collected by by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Introduction

The Simulation Hypothesis is a provocative idea that what we perceive as physical reality is actually an artificial simulation, akin to a sophisticated computer program or virtual reality en.wikipedia.org. In this view, conscious beings and the laws of nature are generated by computational processes, potentially run by an advanced “programmer” or intelligence. This hypothesis, popularized in contemporary philosophy and science fiction, raises fundamental questions about the nature of mind and matter. In parallel, classical Islamic theology offers the concept of occasionalism, especially as articulated by the 11th-century thinker Abu Hamid al-Ghazali. Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is a philosophical doctrine asserting that all causal interactions are mediated by a divine agent, with created substances lacking inherent causal efficacy themuslimtimes.info. In other words, only God is the true cause of every event; what we call “natural causes” are merely sequential occurrences willed by God at each moment. This essay will explore the simulation hypothesis from both scientific and philosophical perspectives – including Bostrom’s argument, computationalism, and digital metaphysics – and argue how this paradigm can conceptually support or transition into al-Ghazali’s occasionalism. By examining metaphysical parallels, scriptural resonances, and insights from contemporary thinkers (both Islamic and analytic), we aim to show that a simulated-universe framework can serve as a modern metaphor for understanding divine action as envisioned in occasionalism.

The Simulation Hypothesis: Scientific and Philosophical Variants

At its core, the simulation hypothesis posits that our reality might be a simulated construct rather than a base physical reality en.wikipedia.org. This idea gained rigorous formulation through the work of philosopher Nick Bostrom. In 2003, Bostrom proposed a famous trilemma known as the simulation argument, which reasons that at least one of the following propositions must be true: (1) almost no civilizations at our level of development ever reach a “posthuman” stage capable of running high-fidelity ancestor simulations (because they go extinct before then); (2) if such civilizations do reach that stage, almost none of them choose to run simulations of their ancestors; or (3) if those two propositions are false, then “the probability that we are living in a simulation is close to one” scientificamerican.com. In Bostrom’s words, a sufficiently advanced civilization with immense computing power could create so many simulated worlds with conscious beings that “a randomly chosen conscious entity would almost certainly be in a simulation” en.wikipedia.org. Bostrom’s argument does not claim outright that we are in a simulation, but it uses statistical and logical reasoning to suggest that unless we assume our species will never reach such technological heights or will refrain from using them, we should accept a high probability that our own reality is artificially generated scientificamerican.com en.wikipedia.org. A key assumption here is computationalism in the philosophy of mind: the idea that consciousness can arise from the execution of the right algorithms. Bostrom explicitly notes that his scenario assumes “consciousness is not uniquely tied to biological brains but can arise from any system that implements the right computational structures and processes” en.wikipedia.org, meaning that simulated people in a computer could be fully conscious like us if the simulation is detailed enough.

Beyond Bostrom’s argument, the simulation hypothesis connects with a broader trend in science and philosophy that views information and computation as the foundation of reality. Decades before Bostrom, scientists and thinkers had already begun exploring “digital metaphysics” or digital physics – the notion that physical processes might be equivalent to, or emergent from, computation. In 1969, computer pioneer Konrad Zuse proposed in his book Rechnender Raum (Calculating Space) that the universe is essentially a giant computer executing algorithms, effectively treating the laws of physics as computational rulesen.wikipedia.org. This was one of the earliest explicit suggestions that reality might be discrete and digital at bottom, an idea that later became known as digital physics. Similarly, physicist John Wheeler coined the phrase “it from bit”, suggesting that every physical “it” (object, event) ultimately arises from binary choices or bits – in other words, information underlies matter. Roboticist Hans Moravec further popularized these ideas in the 1980s and 90s by speculating about advanced artificial intelligence and even suggesting that our current reality could be a simulation created by future intelligent beings as a form of experiment or entertainmenten.wikipedia.org. Such perspectives treat the universe as a kind of program running on an unknown computational substrate. In these digital metaphysics viewpoints, what we consider natural laws would correspond to the source code or logical rules of the simulation, and the particles and forces are like data structures being updated in each operation cycle.

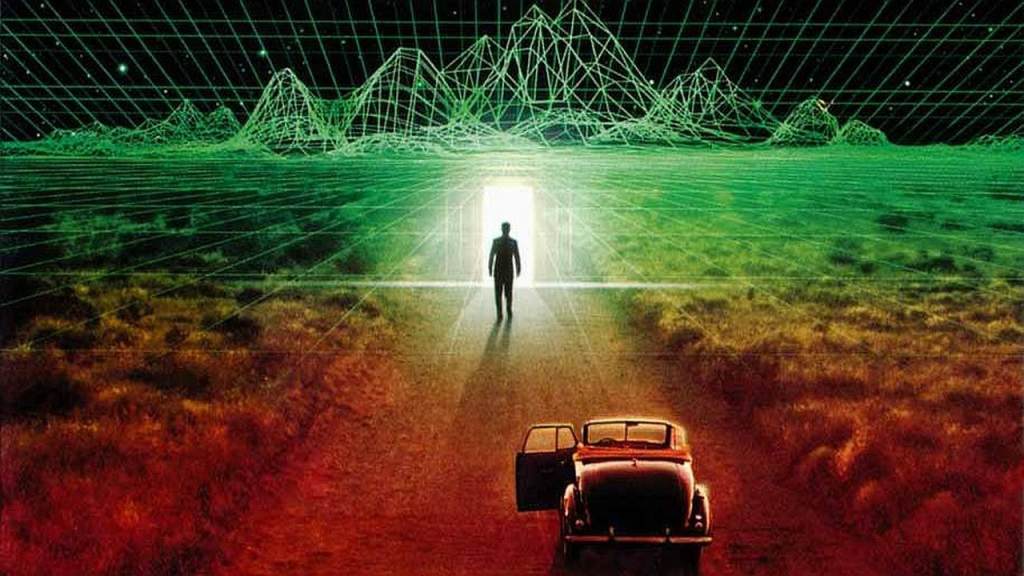

Philosophically, the simulation idea has deep roots. It can be seen as a modern, high-tech twist on classic skepticism scenarios. Plato’s allegory of the cave and Descartes’ evil demon thought experiment both questioned whether the world we experience is the true reality or a mere appearance. The simulation hypothesis echoes these questions in a contemporary idiom, replacing the deceiving demon or shadows on a cave wall with a supercomputer that feeds us an artificial stream of experiences. In analytic philosophy of mind, scenarios like the “brain in a vat” (imagine a brain hooked to a computer receiving fake inputs) anticipated the logic of simulation arguments. More recently, philosopher David Chalmers in Reality+ (2022) has treated the Matrix/simulation scenario as a serious metaphysical proposition, arguing that a virtual world implemented in a computer can still be considered a “real” world with its own consistent laws – it’s just underlaid by different stuff (bits instead of quarks). Chalmers even whimsically rephrased the biblical creation story in digital terms: “God said ‘Let there be bits!’ And there were bits” gerald-baron.medium.com, highlighting the parallel between a divine creation ex nihilo and a programmer initializing a simulation. Thus, both in science and philosophy, a spectrum of computationalist theories and simulation scenarios has emerged: from Bostrom’s probabilistic argument, to proposals that “the universe [is] fundamentally computational” en.wikipedia.org, to thinkers who explicitly entertain that we might be living in a Matrix. All these variants share a common thread: they blur the line between physical existence and virtual information, inviting us to consider that our cosmos could be akin to a rendered world sustained by an external source of computation.

Al-Ghazali’s Occasionalism: Divine Causality and the Critique of Natural Laws

In stark contrast to the scientific imagery of supercomputers and simulations, medieval Islamic philosophy provides its own account of a reality utterly dependent on an external agent: the doctrine of occasionalism championed by al-Ghazali (1058–1111). Al-Ghazali, one of Islam’s most influential theologian-philosophers, articulated this view most famously in his work Tahafut al-Falasifah (The Incoherence of the Philosophers). His occasionalism was formulated as a direct critique of the idea of necessary causal relations in nature, which had been asserted by Muslim Aristotelian philosophers like Ibn Sina (Avicenna). According to al-Ghazali, what we observe as cause and effect in nature is not a binding or inherent connection, but merely the habitual sequence of events orchestrated by God’s will plato.stanford.edu. In the Seventeenth Discussion of the Tahafut, al-Ghazali writes: “The connection between what is habitually believed to be a cause and what is habitually believed to be an effect is not necessary, according to us… Their connection is due to the prior decree of God, who creates them side by side, not to its being necessary in itself, incapable of separation” plato.stanford.edu. He gives concrete examples: fire and burning, food and satiety, medicine and healing – none of these pairs have any intrinsic power to produce the other. If cotton burns when brought near a flame, it is not because the fire necessarily causes burning by its own nature; rather, God has decreed that in normal circumstances He will create the event of burning upon the event of contact with fire plato.stanford.edu. Crucially, al-Ghazali adds that God could decide otherwise: “it is within [divine] power to create satiety without eating, to create death without decapitation, to continue life after decapitation” plato.stanford.edu – statements that underscore God’s absolute volitional freedom to break any observed pattern. The philosophers’ mistake, in al-Ghazali’s view, was to claim that such deviations (miracles) were impossible; al-Ghazali insists they are possible through God’s omnipotence.

Underpinning al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is a particular metaphysical worldview inherited from earlier Ash‘arite kalam (theology). The Ash‘arites developed a form of metaphysical atomism in which both time and matter are composed of indivisible units that are re-created at every moment. Al-Ghazali, adhering to this tradition, viewed the world as a succession of tiny “moments” or occasions, in each of which God directly creates all existent things and their qualities anew plato.stanford.edu. In this view, an apple falls from a tree not because of an innate gravitational force, but because at each instant of its descent God is creating the apple a little lower than before, giving the illusion of continuous motion. As one scholar summarizes the Ash‘arite position: “God rearranges the atoms that make up this world anew at every instant, and in so doing God continuously creates the accidents that inhere in these atomic substances” plato.stanford.edu. An “accident” in this context means a contingent property or event (like the apple’s position or a flame’s heat), which has only a momentary existence unless God recreates it in the next moment. Thus, for al-Ghazali, the world is sustained by God’s will at each and every moment – a doctrine sometimes termed “continuous creation.” There is no independent natural order binding God; what we call laws of nature are simply the regularities of God’s custom (sunnat Allah) which He is free to suspend or alter.

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism was motivated in part by theological concerns, such as safeguarding the possibility of miracles and the principle of God’s omnipotence plato.stanford.edu. If causation were “built into” nature, then even God would be constrained by secondary causes – an unacceptable idea for al-Ghazali’s orthodox theology. By denying intrinsic causal powers to creatures, he upholds that God’s power is absolutely sovereign: no event happens unless God wills it, and whenever an event occurs, it is directly due to God at that very occasion. This was a radical departure from the Aristotelian philosophy of his time, which held that things have fixed natures and causal powers (fire has the nature to burn, bread has the power to nourish, etc.). Al-Ghazali’s stance anticipated aspects of later Western philosophical skepticism about causation (David Hume, centuries later, would similarly deny necessary connections in causality, albeit without invoking God). Interestingly, a version of occasionalism also appeared in 17th-century Europe with thinkers like Nicolas Malebranche, who, influenced by Descartes, argued that only God can mediate interactions between mind and body and indeed between any cause and effect. Malebranche’s view was essentially the same doctrine in a Christian context themuslimtimes.info. Both al-Ghazali and Malebranche, each in their own milieu, asserted that what appear to be natural causes are merely “occasions” for God’s one true causality. Thus, in al-Ghazali’s Islamic occasionalism, we find a picture of reality as a kind of theater of divine volition: atoms flashing in and out of being at God’s command, sequences of events having no binding power on each other, and the entire cosmos essentially “a book” written in real-time by the divine will rather than an autonomous machine.

Parallels Between a Simulated Universe and Occasionalist Doctrine

At first glance, the simulation hypothesis and al-Ghazali’s occasionalism emerge from vastly different intellectual contexts – one from cutting-edge technology and philosophy of mind, the other from medieval theology. Yet, the two paradigms share striking metaphysical parallels that invite comparison. Both present a non-autonomous universe sustained by an external agent (a Programmer or God), and both downplay or eliminate intrinsic causation within the world itself.

1. External Agency and Dependent Reality: In the simulation hypothesis, if our world is a computer simulation, then everything that happens inside the simulation ultimately depends on the “Simulator” – an external intelligent agent or system that runs the code ivysci.com. The simulated universe has no existence or continuity on its own; it exists only as long as the computer is executing the program. This is directly analogous to occasionalism’s view of the world depending entirely on God’s ongoing activity. Just as a simulation’s reality is “entirely dependent on an external agent for its existence and the unfolding of events” themuslimtimes.info, so in al-Ghazali’s occasionalism the cosmos would cease to exist or operate if God stopped willing it at any given moment plato.stanford.edu. The Simulator in a computer model “mirrors the divine agent in occasionalism” themuslimtimes.info: both are transcendent to the world they sustain, and in both cases the world has no self-sustaining power.

2. Absence of Intrinsic Causality: Within a simulated universe, the entities and objects have no genuine causal power of their own – any time one object “affects” another on screen, it is in reality the underlying code and processor that determines this outcome. A video game character does not truly cause an explosion by flipping a switch; rather, the program’s rules update the game state to show an explosion when that action occurs. Likewise, in occasionalism, a lit match does not inherently cause a piece of paper to ignite; God directly causes the ignition when the match is struck, according to His customary rule plato.stanford.edu. In both frameworks, causal relations as perceived by the inhabitants are secondary appearances. An observer inside the system perceives consistent cause-and-effect (just as we see physical causality), but “these interactions are orchestrated by an external agent – God in occasionalism and the simulator in the simulation hypothesis” themuslimtimes.info. The regularities do not stem from the things themselves. In modern terms, we could say that what we call laws of nature are, in an occasionalist view, like the software of a simulation – a set of instructions that the external agent follows in producing phenomena. If either the divine will or the simulation program were to change, the observed causal patterns would change accordingly. This is why al-Ghazali could countenance the logical possibility of fire not burning cotton or of people remaining alive without hearts – he believed there is nothing necessary in the objects themselves that enforces those outcomes plato.stanford.edu. It is all contingent on the will (or code) of the external factor.

3. Continuous Updating or “Rendering” of Reality: Both models involve a kind of continuous, fine-grained production of the world’s state. In a digital simulation, especially a high-resolution one, the system updates the attributes and positions of every object at each time-step (frame) based on the programmed rules. This is reminiscent of the Ash‘arite idea that God recreates the universe at each instant. The Ash‘arite metaphysics even posited a discrete time granularity – almost as if the universe’s state is refreshed in a series of Divine “clock cycles.” One could say the world is being “rendered” afresh by God at each moment, just as a computer continually renders graphics and events in a virtual environment. Modern commentators have picked up on this parallel: if we inhabit a simulation, the simulator must actively calculate and supply the existence of every entity and event, which strongly parallels the occasionalist notion of continuous divine creation plato.stanford.edu. In fact, occasionalism has an argument called “conservation is constant creation” – the idea that God “conserving” the world (keeping it in existence) from moment to moment is effectively the same as creating it ex nihilo anew each moment plato.stanford.edu. In a simulation, preserving the state is likewise an active computational process, not a passive enduring of an object. If the computer program halted, the simulated world would not gradually decay – it would vanish or freeze entirely. Similarly, without God’s constant creative act, the occasionalist world would not gradually wind down; it simply would not be at all. This utter contingency of the world on an external source is a shared structural feature of both conceptions.

4. “Laws” as Flexible and Contingent: In both the simulation framework and occasionalism, what we think of as inviolable natural laws are in fact contingent on the will or design of the external agent. A simulation’s rules (the code) could, in principle, be altered by the programmer at any time – analogous to a miracle in religious terms. For example, the simulator could suspend gravity in the program, or instantly heal a character’s injuries by editing variables. From the inside, such an event would appear miraculous – a break in the usual causal order – but for the programmer it is simply an intervention, a tweak of the software. Occasionalism makes exactly the same point regarding God and miracles: since “no limitation on divine power is justified, unless a state of affairs is logically inconsistent” plato.stanford.edu, God can at any time override the normal course of nature. The possibility of miracles is built-in and expected in occasionalism, just as a simulation allows for the possibility that the controller can spawn or remove objects at will. In day-to-day terms, both scenarios explain why nature usually behaves consistently (because the external agent typically imposes stable rules – whether out of logical necessity or by choice), yet they both allow that this consistency could be suspended. In a way, the simulation hypothesis provides a secular analog for miracles: if we saw the laws of physics break down tomorrow, a scientist might either consider a divine miracle or, equivalently, that the simulation got reprogrammed or glitched by the simulator.

Given these parallels, it is not surprising that recent writers have explicitly drawn the analogy. One commentator notes that “if we inhabit a simulation, the role of the simulator mirrors the divine agent in occasionalism” and that both pictures depict a world where entities are “entirely dependent on an external agent for their existence and the unfolding of events” themuslimtimes.info. Another scholar, H. Kam, reflecting on Islamic theology and simulation theory, writes that the hypothesis “introduces a reality model where a Simulator, resembling a divine figure, controls the simulation in a way akin to religious teachings” ivysci.com. The language here—comparing the simulator to a divine figure—is telling: it suggests that, conceptually, a sufficiently powerful simulator within a simulation narrative plays a role almost indistinguishable from God in a traditional creation narrative. Indeed, some have gone so far as to suggest that the simulation hypothesis could be “a new kind of religion” or at least a bridge to religious thinking for a technological age everand.com. While a human programmer is not omnipotent in the absolute sense, from the perspective of the simulated beings the programmer is omnipotent relative to their world. The programmer can edit constants of nature, answer prayers (requests) if they so chose, or even terminate the simulation – powers analogous to the divine attributes of omnipotence and omniscience within that enclosed reality. In a colorful synthesis of these ideas, one writer asks: “The Divine Programmer: Is God a Cosmic Coder?”, noting that “if God is the grand programmer, then reality is His code, and our consciousness is but a variable of divine intelligence running within it” medium.com. This metaphor captures in plain terms the intuitive alignment of the simulation concept with the idea of a universe sustained by God’s mind or command.

Of course, one must acknowledge differences in nuance. Al-Ghazali’s God is a transcendent, singular deity with purposes and wisdom, whereas a simulator in, say, Bostrom’s scenario might be an advanced but finite being within a higher universe (or a future human running “ancestor simulations”). Theologically inclined thinkers might respond that even if our immediate simulator were not God, the regress of simulations must end in a base reality – and the ultimate author of all layers of reality could be identified with God. In any case, the structural similarity stands: both frameworks envision our experienced world as a kind of derivative reality – not the ultimate ontological foundation, but a dependent reality continuously sustained and governed by an external will or intellect. This structural similarity is what makes the simulation hypothesis a useful conceptual tool for illuminating occasionalism in modern terms.

Scriptural and Theological Resonances in Islam

Interestingly, the image of reality being continuously governed moment-by-moment by a higher power is not only a theoretical abstraction of theologians like al-Ghazali; it also finds resonance in the scriptural language of the Qur’an and Islamic metaphysics. The Qur’an contains numerous verses that emphasize Allah’s exhaustive knowledge and active decree over every event in the universe. These verses can be read as poetic descriptions of a world that is constantly under divine surveillance and control – notions that align well with the idea of a “divine program” or continuous rendering. For instance, Surah Al-An‘am 6:59 states: “And with Him are the keys of the unseen; none knows them except Him. And He knows what is on the land and in the sea. Not a leaf falls but that He knows it. And no grain is there within the darkness of the earth and nothing moist or dry but that it is [written] in a clear record.” legacy.quran.com. This vivid image – not even a single leaf falls from a tree without God’s knowledge, and everything is already written in a clear Record (Kitabun Mubeen) – evokes the idea of a comprehensive information database of reality. The notion of a “clear record” in which all events are written has a striking parallel in simulation terms: one might think of the system logs or the underlying data structures that track every entity in the simulation. The Qur’anic language suggests a pre-existing script or plan for every occurrence, which is analogous to a program’s code determining outcomes ahead of time (yet requiring the processor’s action to manifest them).

Another verse, Yunus 10:61, reinforces this: “And you are not engaged in any matter, nor do you recite any Quran, nor do you do any deed, except that We are witness over you when you are involved in it. And not absent from your Lord is any part of an atom’s weight within the earth or within the heaven, or anything smaller than that or greater, but that it is in a clear Register.” legacy.quran.com. Here God’s omnipresence and omniscience are described in almost forensic detail: nothing, not even the smallest particle (an atom or less), escapes divine awareness and recording. The phrase “We are witness over you when you are involved in it” implies real-time monitoring of every action. In a computational analogy, one is reminded of how every operation in a digital system can be monitored and recorded by the system administrator or how every bit change is in principle accessible. The verse also mentions the Kitabun Mubeen (clear Register) again, underscoring that all happenings are in some sense already accounted for in God’s ledger before they occur. This strongly resonates with the idea of predestination (qadar) in Islamic theology – that all events, down to the tiniest, unfold according to God’s knowledge and decree. In simulation language, one could compare this to the concept that every event is part of the program’s design (or at least anticipated by it). It is as if the universe runs on a Divine algorithm, with no “random” or unplanned outcomes outside God’s knowledge.

Surah Al-Hadid 57:22 takes the idea of pre-recording even further: “No disaster strikes upon the earth or among yourselves except that it is in a Register before We bring it into being – indeed that, for Allah, is easy.” legacy.quran.com. This verse explicitly says that every calamity or event is already written in a register before it happens, and that bringing it into actual existence is “easy” for God. The temporal language here (“before We bring it into being”) maps neatly onto the simulation analogy: it is as if the source code or data for an event exists, and then it is rendered into the simulation. The effortlessness (“easy for Allah”) might be likened to how trivial it is for a computer program to instantiate an object or scenario once the code is in place. From a theological perspective, this verse conveys that Allah’s will and knowledge precede the material world and that realization of any event is just a matter of executing what has already been decreed. The concept of a pre-existing divine Register (often interpreted as the Preserved Tablet, al-Lawh al-Mahfuz) parallels the idea of a “hard drive” containing all information that will ever unfold – a divine database that the “program” of the universe references at every moment.

A particularly evocative verse is found in Ya-Sin 36:12: “Indeed, We give life to the dead, and We record what they have put forth and what they left behind, and We have enumerated everything in a clear Register.” medium.com. This verse combines the theme of resurrection (“give life to the dead”) with the theme of complete accounting: “everything” is enumerated in the clear Register. The word “enumerated” is key – it implies quantification and listing, much as a computer might store the state of every variable. Classical commentators explain that God records all of a person’s deeds (“what they send ahead”) and the effects of those deeds in the world (“what they leave behind”) dyeing.thebluebook.co.za. The image is that of an all-encompassing record that not only registers direct actions but even their ripple effects (“traces” or footprints). In modern terms, one is reminded of a system that logs not only user actions but also secondary consequences, or a version control that keeps every change. Islamic metaphysics often describes this world as continuously overseen and recorded by angels (e.g., the Kiraman Katibin, noble scribes, in Qur’an 82:10-12 who “know all that you do”). All of these metaphors paint a picture of a universe that is far from a clockwork left to run on its own; rather, it is under constant observation and governance. The Qur’anic worldview, especially as interpreted by occasionalist theologians, is that at each moment God is actively engaged in “maintaining” the world. The Qur’an says, “Allah holds the heavens and earth, lest they cease” (35:41) and “Every day He is bringing about a matter” (55:29), verses that the commentators read as indicating perpetual divine sustainment and action. This aligns perfectly with the idea of constant divine “updating” or “rendering” of events: nothing sustains itself, and every occurrence is a fresh act of creation.

From an occasionalist standpoint, these scriptures provide the revealed backing for their doctrine: If not a leaf falls without God’s knowledge (and by implication, permission), and if every motion is written in advance, then there is no room for independent causal power in the leaf or the tree or the wind – it’s all under divine control. The simulation analogy can make these classical religious concepts more accessible to contemporary minds: One can think of God’s knowledge “inscribing” everything in a book as analogous to how a computer simulation might have a complete state-space or log of the world. The difference, of course, is that God’s knowledge is not passive data – in Islamic doctrine, His knowledge is coupled with His will and power, meaning that what is written happens because He wills it so. To use the analogy, God not only has the code, He is also the processor executing it, and He can modify it at any time. There is even a strand of Islamic thought, especially among Sufis, that describes the world as tajalli, a continuous manifestation of God’s attributes, almost like frames of a movie reel appearing in sequence through God’s emanation. Ibn Arabi, a renowned 13th-century Sufi mystic, spoke of the world as an illusion or a dream within God’s infinite consciousness – “The universe is His shadow, and He is its light… a shadow is nothing in itself, just as existence is nothing apart from Him” medium.com. Such descriptions bear a poetic resemblance to simulation language: our existence is a projection of the Real (God), just as a simulation is a projection of the real computer’s operations; remove the source, and the shadow or virtual world is “nothing in itself.”

In summary, Islamic scripture and metaphysics resonate with the idea that the world is continuously dependent on God’s command. The Qur’anic emphasis on all-encompassing divine knowledge and the imagery of a pre-written register of all events provide a theological framework that is highly compatible with occasionalism – and by extension, offers a rich template for comparison with the simulation paradigm. The notion of God “rendering” reality in each instant maps onto both the Ash‘arite atomistic view and the modern computational view. This resonance suggests that using the simulation metaphor is not a contrived exercise, but rather an organic way to translate ancient concepts of divine sustenance into a modern idiom. The scriptures already describe something akin to a cosmological information process (everything numbered, recorded, brought into being in sequence by God), and thus lend themselves to the comparison.

Contemporary Engagements: Islamic and Analytic Perspectives on Digital Metaphysics and Causality

The convergence of ideas between a high-tech simulation hypothesis and classical theological occasionalism has not gone unnoticed by contemporary thinkers. In fact, it has become a topic of interdisciplinary exploration, engaging philosophers, theologians, and even computer scientists. On the Islamic side, a number of modern scholars and writers have begun to explicitly draw parallels between digital metaphysics and Islamic concepts of contingency and creation. For example, Rizwan Virk, a technologist and author who studies the simulation hypothesis, has explored how these ideas interface with religious worldviews. He notes that the simulation hypothesis can “bridge an increasingly scientific and technological society… and those of faith”, giving secular people a way to conceive of a higher reality using the video game metaphor everand.com. In a comparative study, Virk highlights correspondences such as the Islamic belief in unseen entities (angels, jinn) and recorded deeds (the “Scroll of Deeds”) with the layers and logging of a simulated world everand.com. Essentially, he suggests that many aspects of Islamic cosmology (a temporary world dunya vs. a real afterlife akhira, the idea of this life as a test observed by God, etc.) can be explained in simulation terms – akin to how players in a simulation are given objectives and monitored, with the real consequences or “score” being kept outside the simulation.

Academic philosophers have also weighed in. The aforementioned Hureyre Kam, writing in the Journal of Muslims in Europe, argues that simulation theory and Islamic theology share a deep consonance. He points out that a simulated universe “challenges conventional perspectives” by introducing a model where a higher intelligence (Simulator) is in control, which “aligns with intelligent design, challenging a chance-based universe” ivysci.com. This effectively revitalizes the argument from design using modern technology – if our world is intentionally programmed, it strongly implies a designer. Kam also notes that the simulation idea “accentuates the potential for an afterlife” ivysci.com, since in a simulation paradigm, one can easily imagine the program continuing (or the soul being transferred to another “server” so to speak) after the physical parameters here end. These points show how digital metaphysics can resonate with religious concepts of purpose and afterlife. Another area of engagement is the classical argument from contingency: philosophers such as Gottfried Leibniz asked why there is something rather than nothing, concluding that the contingent world requires a necessary being as its explanation. The simulation hypothesis recasts this in a new light – it prompts the question of what “platform” our reality runs on. If indeed our universe is simulated, it is by definition contingent on the higher reality containing the simulator. This can lead to a renewed form of the cosmological argument: tracing the hierarchy of simulations ultimately requires an uncaused cause or an original “programmer” that is not itself simulated themuslimtimes.info. Some theistic philosophers have seized on this: notably, David Chalmers (an analytic philosopher of mind, though an atheist himself) has provocatively suggested that if we are in a simulation, then the creator of that simulation meets many of the definitions of God (powerful, intelligent, the source of our world) gerald-baron.medium.com. Chalmers observed that among arguments for God’s existence, the simulation hypothesis curiously “may be the strongest” in the sense that it gives even a skeptic a logical route to acknowledging a creator figure gerald-baron.medium.com. He stops short of equating the simulator with a theological God (since the simulator could be a finite being in another cosmos), but the analogy is hard to escape – particularly if one asks, who created the creators? Eventually, one might posit a supreme Creator at the top of the chain, which in effect is God by another name.

Within Islamic thought, occasionalism itself has seen renewed interest due to these modern discussions. Scholars have re-examined al-Ghazali’s ideas in light of quantum physics and indeterminacy, for instance, suggesting that the probabilistic nature of quantum events and the lack of clear causality at the subatomic level could be interpreted in an occasionalist framework (with God’s will determining each outcome) thequran.love. While such interpretations remain speculative, they show the appetite for linking classical kalam to contemporary science. The simulation hypothesis adds another layer to this: it provides a mechanical model for how occasionalism could be true. Instead of imagining an invisible metaphysical act, one can picture a computational process underneath reality. Some Islamic scholars have found this useful in apologetics – explaining miracles or divine action by analogizing to the ease with which a programmer can patch a running simulation makes the concept less abstract. It is essentially using a modern parable to convey an old idea. Preachers have even referenced The Matrix film to illustrate the Islamic teaching that the material world is an illusion compared to the hereafter. The line between analogy and literal theory can blur: a few voices have mused that perhaps God does operate via something like a simulation – not that God needs a computer, but that the logical structure of creation could be algorithmic. After all, if we consider God’s kun fayakun (“Be, and it is”) command, it is reminiscent of a single instruction causing an outcome. Some thinkers in the Islamic tradition (like the Brethren of Purity, Ikhwan al-Safa, in medieval times) even toyed with proto-computational ideas, conceiving of creation in terms of divine words, letters, and numbers (which could be seen as information theory in embryonic form).

Analytic philosophy of mind contributes to the conversation as well. If minds can be simulated, as many cognitive scientists hold (the brain being essentially a biological computer), then one might view human free will and determinism in a new light. Ibn Arabi’s perspective on free will was mentioned earlier: he believed our sense of independence is illusory and that “the will of God is behind everything done”, comparing humans to characters in a scripted play medium.com. This parallels the debate in simulation theory about whether simulated beings could have free will if their actions are ultimately determined by code. Some argue a sufficiently complex simulation could allow emergent patterns that the programmer doesn’t micromanage (just as in Islamic theology, the Ash‘arites developed the doctrine of “acquisition” to reconcile human responsibility with divine causation). Others, like strict determinists, might say both models (occasionalist and simulationist) imply a kind of fatalism: we are “programs following the code that underlies reality” medium.com. These interdisciplinary discussions show that the convergence of simulation and occasionalism is not merely fanciful; it leads into classic philosophical problems of free will, ethics, and meaning. If one accepts the simulation hypothesis, one is almost pushed into an occasionalist outlook on life – viewing daily causation as surface-level and seeking the intention of the “programmer” as the true explanation.

Finally, it’s worth noting that not everyone is fully on board with merging these ideas. Some theologians caution against taking the simulation analogy too literally, lest it reduce God to just a super-engineer and life to a software game. They remind that metaphors can illuminate but also distort: God’s creation is ex nihilo (from nothing), whereas a computer always needs pre-existing hardware and energy. Moreover, God in Islam is absolute Reality (al-Haqq), whereas a simulation is considered something less real than its platform. Nonetheless, as a conceptual bridge, the simulation paradigm has proven remarkably fruitful. It has enabled a new generation to appreciate occasionalism not as a dusty, arcane doctrine, but as a live option in understanding reality – one that intriguingly dovetails with cutting-edge ideas in physics and computer science. By engaging with voices from both Islamic theology and analytic philosophy, we see a rich dialogue forming. Each side provides insights to the other: the simulation hypothesis provides a concrete model for visualizing how a world could be dependent on an external will, and occasionalism provides a deep metaphysical and ethical context (e.g. the idea of purpose and moral accountability set by the Creator) that pure simulation theory lacks. Together, they converge on the notion of contingency: that the world is not a brute fact, but contingent upon something beyond it – whether we call that “something” a computer in another universe or God.

Conclusion

The simulation hypothesis and al-Ghazali’s occasionalism, despite their disparate origins, converge on a profound idea: the world as we experience it is not the ultimate reality but a dependent reality, sustained at every moment by an external agency. Through this exploration, we have seen how the language of modern science and simulation provides a powerful metaphorical framework for classical theological insights. Bostrom’s simulation argument and the broader digital physics paradigm invite us to consider a universe in which information and computation reign beneath appearances – a universe that could be switched off or reprogrammed by its architect. Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism, grounded in Islamic doctrine, portrays a universe where physical causes have no autonomous efficacy and every occurrence is directly given by the fiat of the Almighty. Conceptually, the simulation framework supports occasionalism by offering an intuitive model of how a world could look law-abiding on the surface yet be completely governed “under the hood” by a transcendent will (or code). It transforms al-Ghazali’s premodern analogies (like the king moving images in a mirror) into 21st-century terms (a programmer rendering scenes in a computer) without losing the essence: that causality as we perceive it is a secondary illusion, and true causation comes from outside the system.

Moreover, using the simulation hypothesis as a metaphor for divine creation can reinvigorate classical theological insights in contemporary discourse. It provides relatable imagery for age-old concepts: We can speak of God as the ultimate “Programmer” not to reduce God to a finite being, but to illustrate sovereignty and creativity in terms people today readily grasp. The Qur’anic depiction of a God who “writes” destiny in a register and knows even the fall of a leaf fits neatly with the idea of a programmed world – it shows that, at the level of meaning, pre-modern spirituality and post-modern simulationism are not antagonists but allies in describing a reality grounded in mind and intention rather than blind matter. This alliance also opens up new discussions: for instance, ethical questions about simulated beings’ rights mirror questions of our duties to God and each other if life is a divinely authored test. It also challenges us to consider our own metaphysical status: If we are “characters” in a divinely generated narrative, our freedom and moral responsibility might need to be understood the way one understands player-characters in a game, or actors improvising within a script – bounded yet meaningful.

Ultimately, whether one literally believes we live in a computer simulation or not, the exercise of comparing it to occasionalism is enlightening. It shows that science and technology may be recapitulating, in new language, some of the insights that theological metaphysics arrived at long ago. The simulation hypothesis as a metaphor underscores the contingency, fragility, and purpose-driven nature of the universe, themes that lie at the heart of religious worldviews. It serves as a modern parable: just as Neo in The Matrix had to awaken to a higher reality, al-Ghazali implores us to see beyond the veil of cause-and-effect to the reality of divine agency. In a sense, the simulation hypothesis could be seen as a bridge to transcendence for a secular age – a way to conceive that what’s empirically “real” might itself be dependent on a higher order of reality. Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism gives that notion a spiritually rich interpretation: that higher reality is not an alien computer, but a compassionate God who sustains the world out of wisdom and who can rewrite the script at will. Thus, the paradigm of a simulated universe can indeed serve as a powerful metaphor (if not a literal model) for divine occasionalism, breathing new life into classical theological insights and stimulating a dialogue where faith and reason, past and future, intersect. In the end, both frameworks remind us of the same humbling truth – that the world as we know it may be but a set of signs (ayat) pointing beyond itself, inviting us to seek the ultimate Source that lets the world be. themuslimtimes.info

Leave a reply to A Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Commentary on Qur’an 31:27–28 – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply