Epigraph:

He is the First and the Last, and the Manifest and the Hidden, and He knows all things full well. He it is Who created the heavens and the earth in six periods, then He settled Himself on the Throne. He knows what enters the earth and what comes out of it, and what comes down from heaven and what goes up into it. And He is with you wheresoever you may be. And Allah sees all that you do. (Al Quran 57:3-4)

Written and collected by by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Introduction: The article “From Simulated Universes to Occasionalist Metaphysics: Bridging the Simulation Hypothesis and al-Ghazali’s Occasionalism” by Zia H. Shah explores an intriguing dialogue between a cutting-edge idea in science/philosophy – the Simulation Hypothesis – and a classical Islamic theological doctrine – al-Ghazali’s occasionalism. In summary, the author explains how the notion that our universe might be a kind of simulation parallels al-Ghazali’s view that every event in the world is directly caused by God’s will. By examining these parallels, citing Qur’anic verses, and engaging contemporary thinkers, the article shows that the simulation metaphor can illuminate traditional Islamic concepts of divine agency in modern terms thequran.love. Below is a summary of the article’s key points, followed by a discussion of how al-Ghazali’s doctrine of occasionalism (as presented) can deepen Muslims’ connection to the Qur’an, inspire engagement with philosophy and science, and serve as a unifying paradigm for Muslims focused on the oneness of God’s action.

Summary of the Article

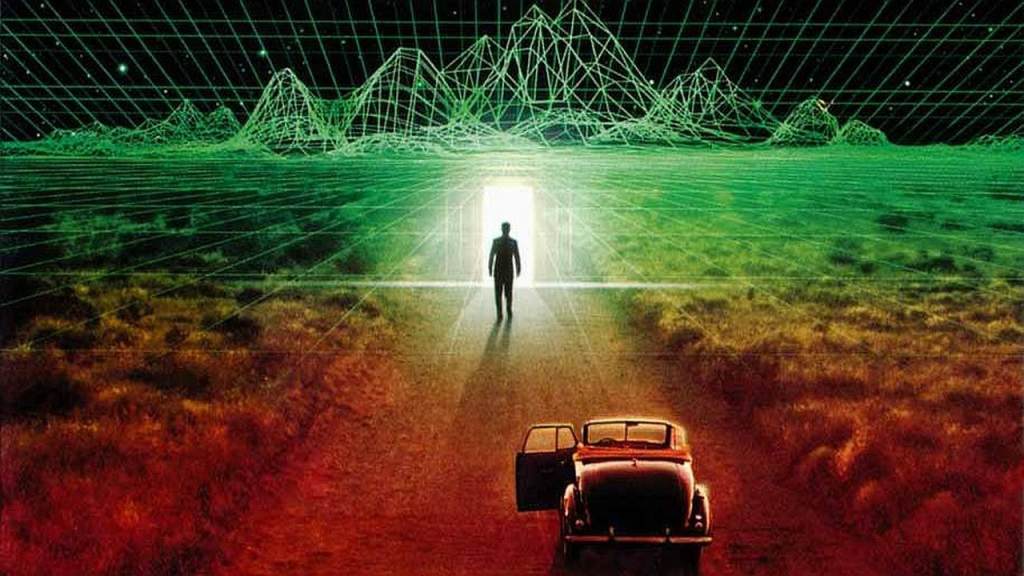

The Simulation Hypothesis – Reality as a Program: The article begins by outlining the simulation hypothesis, which posits that our reality might be an artificial simulation rather than a base physical reality thequran.love. Philosopher Nick Bostrom’s famous simulation argument is summarized: either advanced civilizations never reach the capability to run “ancestor-simulations,” or if they do, they refrain from doing so – otherwise (if those two conditions are false) it is highly probable that we ourselves are living in a simulation thequran.love. In Bostrom’s reasoning, a sufficiently advanced “programmer” could create countless simulated worlds with conscious beings, making it statistically likely that any given conscious entity (like us) exists in one of those simulations thequran.love. Beyond Bostrom, the article notes that scientists and philosophers have developed broader “digital physics” ideas, treating the universe as fundamentally computational. For example, as early as 1969, Konrad Zuse suggested the universe is a giant computing machine running cosmic code, and physicist John Wheeler later coined “it from bit,” implying that information (bits) underlies every physical “thing.” These ideas, along with science-fiction scenarios like The Matrix, blur the line between physical existence and computer simulation. Philosophers such as Plato (with the cave allegory), Descartes (evil demon scenario), and modern thinkers like David Chalmers (who joked “God said ‘Let there be bits!’ and there were bits”) are cited to show that questioning the reality of the world has deep roots. All these threads converge on the notion that our cosmos could be akin to a rendered world sustained by an external source of computation – in other words, reality might be something like a programmed illusion sustained by a transcendent “processor.”

Al-Ghazali’s Occasionalism – God as the Only True Cause: In contrast to the computer-oriented imagery above, classical Islamic theology offers its own model of a world fully dependent on an external agent. The article introduces Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058–1111) – one of Islam’s most influential theologian-philosophers – and his doctrine of occasionalism, articulated in his work Tahāfut al-Falāsifah (The Incoherence of the Philosophers). Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism was a direct critique of the idea of necessary causal relations in nature held by the Islamic Aristotelians (like Ibn Sina/Avicenna) thequran.love. According to al-Ghazali, what we call “cause and effect” in the natural world is not a binding, intrinsic connection – it is simply the habitual sequence of events set by God’s will thequran.love. He famously wrote that “the connection between what is habitually believed to be a cause and what is habitually believed to be an effect is not necessary… Their connection is due to the prior decree of God, who creates them side by side, not to its being necessary in itself” thequran.love. In practical terms, fire does not burn cotton by any power of its own; rather, God creates the burning whenever fire is put in contact with cotton. Al-Ghazali emphasizes that God can always decide otherwise – it is within divine power to cause effects without their usual material causes or to withhold an effect even when the presumed cause is present (for example, God could cause a person to survive decapitation or create satiation without the person eating food). No physical process has independent efficacy – every event occurs because God directly willed it at that moment. Underlying this view is the Ash‘arite theological notion of “continuous creation”: the world and everything in it are re-created at each instant. Al-Ghazali, following this atomistic view of time and matter, saw the universe as a sequence of momentary “occasions” where God brings everything into being anew at each moment. Thus, an apple falls from a tree because God is continuously creating it at successively lower points in space, giving the appearance of gravity, and a flame feels hot because God is recreating the sensation of heat each instant. Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism was motivated by a theological concern to safeguard God’s omnipotence and the possibility of miracles: if nature had autonomous causal laws, it would impose limits on God’s power, which he deemed unacceptable. By denying any independent causal power to creation, al-Ghazali upholds that no event happens unless God wills it, and whenever something occurs it is directly due to God at that very moment. This worldview portrays reality as a kind of “theater of divine volition” – with “atoms flashing in and out of being at God’s command” and each sequence of events written in real-time by the divine will rather than by any autonomous natural law. In short, occasionalism abolishes natural causation: only God is the true cause behind all that we observe.

Parallels Between a Simulated Universe and Occasionalism: At this point, the article brings together the two seemingly distant ideas. Despite one emerging from modern technology and the other from medieval theology, the simulation hypothesis and al-Ghazali’s occasionalism share striking metaphysical parallels. The author highlights several key similarities that invite a comparison between a programmed simulation and divine occasionalism:

- External Agency Sustaining Reality: In the simulation scenario, everything in the simulated world depends on the external Programmer/Simulator who runs the code – the simulation has no existence of its own if the computer program stops. This mirrors al-Ghazali’s view that the cosmos has no self-sustaining power: it would cease to exist or operate if God stopped willing it at any moment. Just as a game world disappears when the console is turned off, the created universe is utterly dependent on God’s ongoing command for its continuity.

- No Intrinsic Causality Inside the System: Within a video game or simulation, objects obey the code; they have no inherent causal power. If one character “pushes” another off a ledge in the game, it is not truly the character causing it but the underlying program’s instructions. Likewise, in occasionalism, a lit match does not inherently cause a piece of paper to ignite – God directly causes the paper to burn when the match is struck, according to His customary rules thequran.love. In both models, what the inhabitants perceive as cause-and-effect is a kind of illusion or secondary appearance. The consistent patterns we see (fire typically burns paper) are like the rules of the software being executed, not powers of the objects themselves thequran.love. Any apparent causal force in nature is merely God’s habit of acting in the same way in repeated circumstances.

- Continuous “Rendering” of Events: A complex simulation continually updates every element of the virtual world frame by frame. Similarly, occasionalism posits that reality is re-created by God at each instant, akin to a cosmic film reel playing frame-by-frame by divine command. The article notes that Ash‘arite theologians even envisioned time itself as a series of discrete moments (like temporal atoms), an idea analogously like a computer’s clock cycles. One could say the universe is being “rendered afresh” by God in each moment – just as a CPU continually renders the graphics in a game world thequran.love. If God’s will were to pause, creation would not gradually fade – it would simply freeze or vanish, just as a simulation would if the processor halts thequran.love. This emphasizes the utter contingency of the world on the external agent in both views.

- Laws of Nature as Contingent Code: In both a designed simulation and in occasionalism, what look like fixed “laws” of nature are actually flexible rules set by the external agent. A programmer can alter the code at will – change gravity, spawn an object, or break the usual rules of the game – which from inside the simulation would appear as a miraculous anomaly. Likewise, God can override the regularities of nature at any time since nothing obligates Him to follow the usual pattern. Al-Ghazali explicitly asserted that miracles are possible and nature’s laws are only God’s customs (sunnat Allah), not inviolable constraints. The article draws the analogy that a miracle in occasionalist terms is like the divine “Programmer” editing the world’s code. For us, the sun rising daily or gravity pulling objects down is just God choosing to act consistently – but He could choose otherwise, just as a simulator could suspend or tweak the rules of the program. Thus, the stability of natural law is upheld in both scenarios by the choice of the external agent, and not by any necessity in the objects themselves.

Given these parallels, the article points out it’s no surprise that recent writers explicitly compare simulation theory to occasionalism thequran.love. One commentator notes that in a simulation, “the role of the simulator mirrors the divine agent in occasionalism,” with both depicting a world “entirely dependent on an external agent for [its] existence and the unfolding of events.” Another scholar, H. Kam, observes that the simulation hypothesis “introduces a reality model where a Simulator, resembling a divine figure, controls the simulation in a way akin to religious teachings.” In other words, a sufficiently powerful simulator in a hypothetical Matrix-like world would function almost indistinguishably from God (from the perspective of those inside): able to set laws, intervene at will, and sustain the world. Some have even suggested that the simulation idea could become “a new kind of religion” or at least a bridge for secular minds to grasp theological concepts. The article is careful to note differences – for example, Bostrom’s “simulator” could be a finite being in a higher universe, not the Almighty God of Islam – but it suggests that even if our simulator were not the ultimate God, one could ask what that higher reality depends on, ultimately leading to the same question of a final divine source. The structural similarity remains: in both frameworks our experienced world is a dependent, derivative reality governed by an external will or intellectthequran.love. This makes the simulation hypothesis a useful modern metaphor to illustrate occasionalism.

Qur’anic and Theological Resonances: Importantly, the article grounds al-Ghazali’s occasionalist vision in the Islamic scriptural context. It shows that the Qur’an itself contains imagery and assertions that align with the idea of a world under constant divine governance – imagery that now maps intriguingly well to the simulation metaphor. For example, the Qur’an states: “Not a leaf falls but that He [Allah] knows it. Nor is there a grain in the darkness of the earth or anything fresh or dry but it is written in a clear record.” (Surah Al-An‘am 6:59)thequran.love. This verse emphasizes God’s all-encompassing knowledge down to the smallest details of the world – every leaf, every grain is already “written” in a divine Register. The article suggests this evokes a picture of reality akin to a comprehensive information database or script that underlies the worldthequran.lovethequran.love. The mention of a “clear record” (kitabun mubīn) for all events is likened to the idea of source code or system logs in a simulation, which record or determine everything that happensthequran.love. Another verse cited is Yunus 10:61: “You do not engage in any matter, or recite any Qur’an, or perform any deed except that We are witness over you when you are involved in it. And not absent from your Lord is an atom’s weight within the earth or in the heaven or anything smaller or larger, but that it is in a clear Register.”thequran.lovethequran.love. This emphasizes real-time divine monitoring (“We are witness over you”) and again that nothing escapes God’s awareness, all being recorded in that Register. The description sounds remarkably like a universal surveillance or logging system. Likewise, Surah Al-Ḥadid 57:22 is quoted: “No disaster strikes upon the earth or among yourselves except that it is in a Register before We bring it into being – indeed that is easy for Allah.”thequran.love. Here God explicitly says every event is written before it occurs, and that bringing it to pass is “easy” – almost like executing a pre-written programthequran.love. The author notes how “before We bring it into being” maps onto the idea that the data for an event exists in the “memory” of God (the Register) prior to its actualization, and “easy for Allah” parallels how effortless it is for a computer to instantiate an object once the code is therethequran.lovethequran.love. In all these verses, the Qur’an conveys a world under constant supervision and preordination by God. Another powerful image from the Qur’an is in Surah Ya-Sin 36:12: “We give life to the dead, and We record what they have put forward and what they left behind; and We have enumerated everything in a clear Register.”thequran.lovethequran.love. The use of “enumerated everything” again suggests a complete quantification of the world’s events, reminiscent of a computer tallying every bit of information. Classical Islamic theology indeed teaches that God’s angels (like the Kiraman Katibin) record every deed, and that nothing occurs except by God’s decree (qadar) – concepts entirely in harmony with occasionalismthequran.lovethequran.love. The article highlights verses such as “Allah holds the heavens and earth, lest they cease” (Fatir 35:41) and “Every day He is bringing about a matter” (Rahman 55:29) as indicating perpetual divine sustainment and actionthequran.love. In Islamic commentary, these are understood to mean that at every moment God is actively keeping the universe from collapse and is engaged in new acts of creation. In essence, the Qur’anic worldview is that the cosmos is never independent of God – it requires His presence and command at all timesthequran.lovethequran.love. This is exactly what occasionalism asserts philosophically: “nothing sustains itself, and every occurrence is a fresh act of creation”, as the article saysthequran.love. Thus, the doctrine of al-Ghazali is not a speculative add-on to Islam, but rather an attempt to philosophically articulate the Qur’an’s own emphasis on God’s continuous governancethequran.love.

By drawing these parallels, the article argues that using the simulation hypothesis as an analogy can make such classical ideas more relatable to modern Muslims (and even non-Muslims). Talking about God “inscribing” everything in a book can be powerfully reimagined as God programming or logging reality in each instantthequran.love. The analogy is not perfect (God is not literally a computer), but it captures the concept of divine sustenance in a high-tech image. Even Islamic mystics used their own analogies: the Sufi Ibn al-‘Arabi described the world as “an illusion or a dream” within God’s knowledge, saying “The universe is His shadow, and He is its light… a shadow is nothing in itself, just as existence is nothing apart from Him”thequran.love. This poetic description aligns with the idea that if you “remove the source” (the light or the real computer), the shadow or simulation is nothing – again, creation has no reality apart from God. In summary, the Qur’anic and spiritual literature of Islam “resonates with the idea that the world is continuously dependent on God’s command”, providing a revealed backing for occasionalismthequran.love. The simulation metaphor, rather than feeling foreign, turns out to be an organic way to translate these age-old concepts into contemporary languagethequran.love.

Contemporary Engagements and Conclusion: The article notes that this convergence of ideas has sparked interest in both Islamic and Western circles. Modern Muslim scholars and writers have begun explicitly drawing these comparisons between digital metaphysics and Islamic theologythequran.love. For instance, technologist Rizwan Virk points out that the simulation hypothesis can “bridge an increasingly scientific and technological society and those of faith,” by offering secular thinkers a familiar videogame metaphor to conceive of higher realitythequran.love. On the flip side, Islamic thinkers can use it as a pedagogical tool to discuss qadar (divine decree) in terms a tech-oriented generation understands. The interdisciplinary dialogue extends to philosophers of mind and science who, even if not religious, find the simulation idea intersecting with questions of consciousness, free will, and the nature of reality – questions long addressed by theology. By the end, the author concludes that whether or not we literally believe we live in a computer simulation is beside the point; the exercise of comparing it with occasionalism is enlighteningthequran.lovethequran.love. It reveals that modern science and technology may be “recycling” in new terms some profound insights that theologians like al-Ghazali arrived at long ago. Both frameworks – the high-tech simulation and the classical doctrine of divine creation – converge on the idea of a contingent universe: a world that is not a self-explanatory brute fact, but one that relies on something beyond itself (a transcendent will) for its existencethequran.lovethequran.love. The article suggests viewing the simulation hypothesis as a metaphor can “reinvigorate classical theological insights in contemporary discourse”thequran.love. Talking of God as the ultimate “Programmer” or reality as His “code” can illustrate divine sovereignty in terms people today graspthequran.love. It even opens new avenues for reflection – for example, if life is a divinely authored simulation or test, what are our moral responsibilities (the article likens this to considering the “rights” of simulated beings, or our duties to God and each other)thequran.love. Ultimately, the author beautifully says that both the simulation idea and occasionalism remind us of a humbling truth: the world as we know it is a set of signs (ayat) pointing beyond itself, inviting us to seek the ultimate Source that lets the world bethequran.love. In Islamic terms, the universe is full of ayat (signs) of Allah – and thinking in terms of a designed simulation can be like a modern parable, echoing the Qur’anic call to see through the “veil” of material causation and recognize the reality of God’s agencythequran.love. Just as Neo in The Matrix had to awaken to a higher reality, al-Ghazali (and the Qur’an) urge us to awaken to the higher reality of divine will behind all phenomenathequran.love. Thus, the article succeeds in “bridging” the concepts: using one to shed light on the other, enriching both scientific imagination and spiritual understanding.

Closer to the Qur’an: Deepening the Understanding of Divine Will and Causality

Al-Ghazali’s doctrine of occasionalism, as presented in the article, can bring Muslims closer to the Qur’an by deepening their understanding of divine will and causality in creation. At its heart, occasionalism is about Tawḥīd in causation – affirming that Allah is One and absolute in His agency, such that no creature has independent power. This concept resonates strongly with numerous Qur’anic verses that depict Allah as actively controlling all events. When Muslims learn through occasionalism that “no event happens unless God wills it”thequran.love and that what we call causes are merely occasions for God’s will, they are essentially rediscovering a Qur’anic worldview in philosophical terms. For example, the Qur’an says “not a leaf falls but that He knows it… it is all in a clear Register”thequran.love. Instead of reading such a verse abstractly, a believer informed by occasionalism will appreciate that every leaf’s falling is directly governed by Allah – it doesn’t fall independently at all. Al-Ghazali’s teaching underscores that if not even a leaf falls without God’s knowledge and decree, then truly there is “no room for independent causal power in the leaf or the tree or the wind – it’s all under divine control.”thequran.love.

This understanding can profoundly enhance a Muslim’s relationship with the Qur’an. Verses about Allah’s omnipotence and omnipresence gain fresh life and practical meaning. Rather than glossing over statements like “Allah is with you wherever you are” or “He holds the heavens and earth lest they cease”, a Muslim who grasps occasionalism sees these as literal metaphysical truths: at each moment Allah is actively “holding up” the universe and connecting each cause to each effect. Natural phenomena are no longer viewed as autonomous processes but as signs of Allah’s direct involvement. This outlook fosters a deeper khushū‘ (humble awe) and tawakkul (trust in God). If every flame only burns by God’s command, a believer will remember Allah when seeing the fire, knowing that its power is truly God’s power. If medicine heals, it is not the pill itself but “Allah who heals” (as Prophet Abraham says in Qur’an 26:80) – the pill is just a customary occasion. Such a mindset, taught through occasionalism, can eliminate any subtle reliance on or fear of created things; one’s heart turns fully to Allah who alone causes benefit or harm. In essence, occasionalism helps Muslims internalize the message of Qul huwal-Lāhu Aḥad (Say: He is Allah, the One) not just in theology but in the causal structure of the world: Allah is ahad (single/unique) as the source of effects.

Moreover, al-Ghazali’s doctrine can reconcile believers with verses about qadar (divine preordainment). Many Muslims struggle with the concept of predestination versus free will. Occasionalism clarifies that from the divine perspective, every outcome is already written and willed by God (as the Qur’an describes the “Preserved Tablet” or Register)thequran.lovethequran.love. Yet, we still experience making choices, much like characters in a scripted simulation can have locally meaningful choices. By using the simulation analogy (as the article does), Muslims can appreciate that Allah’s prior decree doesn’t make our actions pointless; rather it ensures that His plan encompasses all, while we are still responsible within that plan – just as a player in a game must still play their part even though the game’s design ultimately comes from the developer. This nuanced understanding prevents fatalism and encourages conscious submission. We realize that when the Qur’an says “Allah has power over all things” and “Every day He is bringing about a matter”, it is teaching us to see every moment as an unfolding of Allah’s will. Embracing occasionalism thus brings one closer to the Qur’an by aligning one’s intellectual framework with the Qur’anic portrayal of reality. The text of the Qur’an no longer seems merely devotional or symbolic on these points, but becomes a literal description of how the world works under God’s willthequran.lovethequran.love. This deepened metaphysical understanding nurtures stronger faith: a Muslim can find Allah’s wisdom and purpose in all events (good or bad), recognizing them as direct interactions with divine will rather than random occurrences. In summary, occasionalism turns abstract creed into a vivid lens for seeing Allah’s hand in everything, thereby strengthening one’s connection to the Qur’anic worldview and to Allah Himself.

Engaging Philosophy and Science: Occasionalism as a Modern Metaphysical Framework

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism can also inspire Muslims to engage with sound philosophy and modern science, by presenting a metaphysical framework that is surprisingly compatible with emerging models in contemporary physics and computational theory. Rather than being an archaic idea of the 11th century, occasionalism – as the article demonstrates – speaks directly to some cutting-edge discussions about the nature of reality. This means Muslim thinkers and students can confidently enter conversations in cosmology, quantum physics, or philosophy of mind, armed with a perspective that is both rooted in Islamic theology and in harmony with certain modern paradigms. In an age when science and secular philosophies often dominate the narrative about “how the world works,” occasionalism provides a rigorously developed religious model that holds its own.

One way it encourages engagement is by offering parallels to the Simulation Hypothesis, which has captured popular and scientific imagination. When Muslims articulate occasionalism in terms of a “divine simulation” (as a metaphor), they create a bridge for dialogue. They can, for instance, converse with AI researchers or philosophers like Nick Bostrom about what it means for a world to be information-based or dependent on an external agent. The article quoted Rizwan Virk, who said the simulation idea can “bridge an increasingly scientific and technological society… and those of faith”, giving secular people a way to imagine higher reality in familiar termsthequran.love. This works the other way too: it gives religious people a way to frame their doctrine in scientifically accessible language. When we say “natural laws are like code programmed by God” or “God is the ultimate Programmer of the universe,” these are metaphorical, but they make an ancient belief more palatable and discussable in secular settingsthequran.love. A Muslim scientist or philosopher can use this language to show that belief in God’s governance of the world is not mystical mumbo-jumbo but can be likened to concepts in computer science and cosmology. This invites more Muslims into fields like theoretical physics, digital philosophy, or complexity theory, as they see their theology mirrored there. It also invites scientists to consider theological perspectives: if our best scientific analogy for reality (a computer simulation) features an all-powerful external agent, might the religious concept of God deserve another look? In this way, occasionalism becomes a platform for faith and reason to meet productively, rather than a relic to be hidden away.

Furthermore, occasionalism finds echoes in emerging models of physics, which can energize Muslim engagement with those fields. The article’s focus was on simulation theory, but we can extend the insight: modern physics has indeed been uncovering a less deterministic, more information-driven cosmos – one that in some ways vindicates al-Ghazali’s intuition that nature has no autonomous causal power. For example, in quantum mechanics, phenomena like entanglement and quantum tunneling defy classical cause-and-effect: an entangled particle pair can influence each other instantaneously at a distance (suggesting the connection isn’t local to the particles), and particles can appear through energy barriers they classically shouldn’t cross. Some scholars have noted that “quantum mechanics suggests that Ghazali’s view is more compatible with reality than previously thought.”thequran.love In fact, if one looks at quantum events: an entangled particle doesn’t have an independent causal story (it’s as if some outside coordination is at play), and in quantum tunneling a particle’s appearance on the other side of a barrier “shows that events do not necessarily follow from prior physical states”, which is “precisely Ghazali’s argument” that objects do not produce effects by themselvesthequran.love. While scientists might not invoke God, they are effectively saying nature at its fundamental level doesn’t behave as a clockwork independent machine. This is a remarkable point of contact with occasionalism. An educated Muslim can take interest in quantum physics or cosmology and say: look, our tradition predicted that causality is not built-in to matter – and now physics is hinting the same (with ideas like reality being observer-dependent or the universe arising from quantum information). Similarly, the “it from bit” idea of John Wheeler (that information underlies reality) and advances in digital physics and complexity science all suggest the universe might be more like a computational process than we thoughtthequran.lovethequran.love. This dovetails with al-Ghazali’s notion of Allah continuously “computing” the world into existence moment by moment. Such correspondences can motivate Muslims to delve into these scientific fields, not to prove religion with science, but to participate in expanding human knowledge with the confidence that their faith has meaningful contributions to offer.

By casting occasionalism as a credible metaphysical framework – one that can stand alongside materialism, dualism, or simulationism in philosophical debates – Muslims are inspired to engage in sound philosophy as well. The doctrine itself raises fascinating philosophical questions (about free will, causality, induction, etc.) that have occupied Western philosophers like David Hume (who mirrored al-Ghazali by questioning necessary causation). In the article’s narrative, we saw that occasionalism provides “deep metaphysical and ethical context” that a pure simulation theory lacksthequran.love. For instance, it introduces the idea of purpose and moral accountability under a divine Creator, which can enrich discussions that are otherwise mechanistic. This means Muslims trained in occasionalist thought can join philosophical dialogues, offering perspectives on topics like the mind-body problem (historically, occasionalism was even applied to explain mind-body interaction by Malebranche), the nature of laws of physics, or the problem of induction in science (why we expect the future to follow the past – Hume’s puzzle which occasionalism answers with “because God wills the patterns to continue”). Instead of being intimidated by philosophy and science, Muslims can feel that their intellectual heritage anticipated many modern insights. The article concludes that science and technology may be “recapitulating in new language” some of these insights, suggesting that engagement is not only possible but fruitful.

In summary, al-Ghazali’s occasionalism serves as a bridge for Muslims to enter contemporary intellectual arenas. It shows that faith-based metaphysics can converse with scientific theory. By framing divine action in a way that parallels simulation code or quantum indeterminacy, it becomes easier for a Muslim student or scholar to say “our concept of God’s agency is not at odds with what you’re discovering – in fact, it provides a philosophical big picture for it.” This not only inspires Muslims to pursue knowledge in science and philosophy, but also invites the world of science to ponder metaphysical questions that pure materialism might overlook. Occasionalism, therefore, becomes a compelling framework in the ongoing search for a unified understanding of reality, engaging both iman (faith) and ‘ilm (knowledge) in tandem.

Toward Unity: A Shared Paradigm of Divine Action in the Muslim World

Beyond individual spirituality and intellectual engagement, al-Ghazali’s doctrine of occasionalism could serve as a unifying foundation for the Muslim world by offering a shared paradigm of divine action that transcends sectarian interpretations. One of the beauties of occasionalism as described in the article is its focus on the absolute oneness of God’s agency (Tawḥīd al-af‘āl) – a focus that has the potential to rally Muslims of diverse theological backgrounds around a common core. In Islam, virtually all schools of thought agree that Allah is the sole, omnipotent Lord of the universe. While they may have debated the mechanics of causation or the role of human free will, the fundamental creed that “no power nor might exists except through Allah” (lā ḥawla wa lā quwwata illā bi Allāh) is universal. Occasionalism is essentially a detailed exposition of that creed in terms of how the physical world operates. By adopting this doctrine (or at least its ethos), Muslims can find common ground in acknowledging that every moment and every event is an act of Allah. This can diminish sectarian disputes that historically arose over how to reconcile God’s power with worldly causation, by subsuming all causal chains under God’s will.

For instance, whether one comes from a more philosophical tradition (influenced by Ibn Sina or Maturidi kalam) or a more scripturalist tradition (Salafi/Athari) or a mystical tradition (Sufi), the idea that “no event happens unless God wills it, and whenever an event occurs, it is directly due to God at that very occasion”thequran.love is not contentious – it is essentially a restatement of Qur’anic principles. The differences have usually been about how God’s will relates to secondary causes. Occasionalism settles this by straightforwardly affirming God’s immediate role in all causes, while still acknowledging the observable patterns (God’s custom). If Muslims across theological divides embrace this view, it could neutralize some perennial arguments. For example, debates on miracles or karamat (saintly wonders) could be eased: if all causation is God’s anyway, a miracle is just an unusual instance of His will, which no Muslim denies He can do. The doctrine reinforces an attitude of submission and humility before God’s power that is central to all Islamic sects.

Moreover, occasionalism carries an implicit spiritual egalitarianism: it makes clear that no created thing – whether a person, an idol, a star, or a law of nature – has independent power. This can unite Muslims against various forms of shirk (associating partners with God) or superstition. Whether one’s community tended towards rationalizing (trusting physical cause too much) or towards superstition (attributing power to amulets or jinn), occasionalism corrects both by saying only Allah acts. This unifying message can refocus Muslim devotion and reliance (tawakkul) solely upon Allah. In a practical sense, a farmer, a doctor, and an engineer – Sunni or Shia, Sufi or Salafi – can all agree that when they plant seeds, treat patients, or design machines, the outcome rests in God’s hands ultimately, not merely in techniques or materials. This shared reliance could strengthen the brotherhood (ukhuwwah) because it fosters a collective humility and prayerfulness for success in all endeavors, acknowledging one Master.

Historically, it’s true that not all Muslim theologians embraced occasionalism fully – for instance, some inclined to the idea that Allah created stable secondary causes. But even those opinions usually affirmed that Allah can override any cause and that nothing is independent of Him. Thus, the practical upshot (that Allah has full control) was never in dispute. Presenting occasionalism in a positive, compelling way (as the article does using modern analogies) might encourage various schools to see it not as an “Ash‘ari vs. Mu‘tazili” issue of the past, but as a unifying truth that is already embedded in the Qur’an and Sunnah. It shifts the conversation from polemics to wonder at God’s active presence. When believers center their worldview on God’s constant agency, sectarian differences in interpreting destiny, for example, may pale in comparison to the shared awe of God’s power. It’s a reminder that whether one emphasizes human free will or not, ultimately “Allah prevails over all matters” (12:21) – a unifying conviction.

Additionally, the article noted that even Islamic mystics and philosophers converge on the idea of the world’s utter dependence on God, albeit in different language (like Ibn al-‘Arabi’s “the world is His shadow”) thequran.love. This indicates that occasionialist thinking bridges the gap between the esoteric and exoteric understandings of Islam. A Sufi and a conservative theologian might find common cause here: the theologian says “atoms are recreated by God each instant,” the Sufi says “each instant is a new unveiling of God’s presence” – in essence, they agree that each moment is God’s. Such a paradigm can encourage mutual respect among different Islamic disciplines, seeing each other’s language as pointing to the same truth of divine agency. When this realization dawns, it can reduce intra-faith tensions and increase unity. The unifying effect also extends to how Muslims view the modern world: in an era where many feel a clash between scientific worldview and religious worldview, embracing occasionalism (with its modern-friendly analogies) could unite progressive and traditionalist Muslims. Both can rally around the doctrine that science is just uncovering the patterns of Allah’s action (sunnat Allah), and not a rival explanation. This removes a potential source of division – where one group leans “rationalist” and another “literalist” – by providing a framework that satisfies both the intellect (it has logical consistency and now even scientific resonance) and the text (it is rooted in Qur’anic teachings).

Finally, by reorienting all believers toward the oneness of God’s agency, occasionalism can nurture a pan-Islamic spiritual ethos. The article’s closing thought was that the world is “but a set of signs (ayat) pointing beyond itself, inviting us to seek the ultimate Source”thequran.love. If Muslims, regardless of sect, adopt this vision – that every star in the sky, every drop of rain, every beat of our hearts is a sign of Allah actively sustaining us – then our focus shifts from internal disagreements to a collective sense of shukr (gratitude) and ‘ubudiyyah (servitude) to Allah. It is a paradigm that humbles all of us equally under the might of God and elevates our consciousness to see unity in creation. In such a worldview, differences in juristic opinions or theological details become secondary; what matters is that “Allah is doing something at every moment” and we are all witnessing and submitting to that. This shared metaphysical perspective can truly be a foundation for Muslim unity, because it speaks to the core of faith that every Muslim shares: lā ilāha illā Allāh – there is no creator, no sustainer, no power except Allah.

In conclusion, al-Ghazali’s occasionalism, far from being a mere abstract theory, carries profound implications that can enrich Muslim piety, promote intellectual engagement, and enhance unity. By seeing the cosmos as a grand “simulation” run by Allah, Muslims can feel closer to the Qur’an’s message, finding new wonder in verses about divine will; they can confidently engage modern scientific and philosophical discourse, knowing their faith has a sophisticated interpretative lens; and they can rally together around the simple truth that every atom of the universe is under the one God’s command. This doctrine thus serves as a powerful reminder and a unifying banner: the oneness of God’s agency in the world, which in turn reflects the oneness of the Muslim ummah devoted to that one God. As all things are from Him and depend on Him, so may all hearts come together in His remembrance.

Leave a comment