By Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

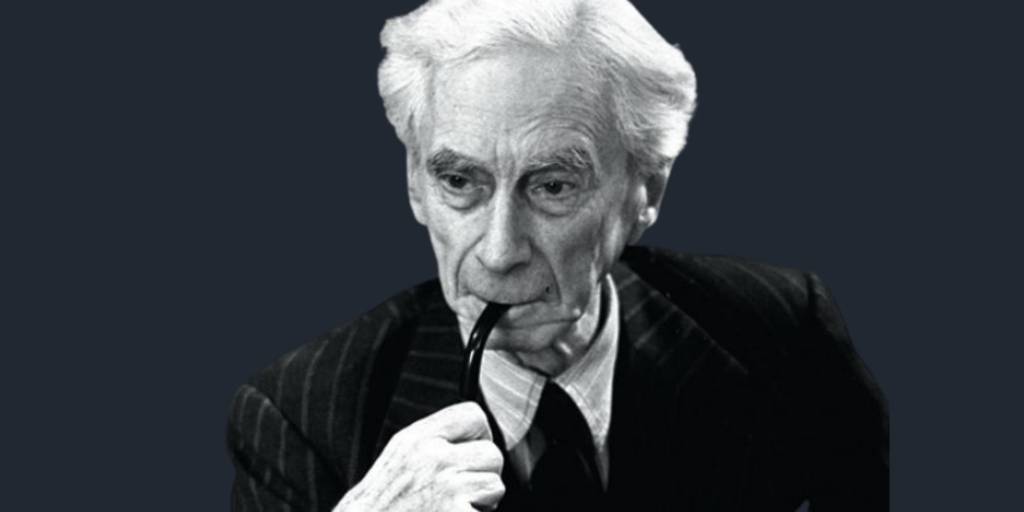

Bertrand Russell famously claimed that he would simply say “the universe is just there, and that’s all,” implying that the existence of the cosmos requires no further explanation. In what follows, we offer a slightly persuasive, scholarly refutation of this stance on two fronts. First, we examine scientific evidence from modern cosmology that challenges the idea of an unexplained, eternal universe. Second, we present a philosophical critique showing why treating the universe as a “brute fact” (something with no cause or reason) is conceptually problematic. Throughout, we highlight how contemporary science and philosophy both point to the implausibility of Russell’s position.

Scientific Refutation: Cosmology Points to a Non-Brute-Fact Universe

Big Bang Cosmology and a Finite Beginning in Time

Modern cosmology has overwhelmingly established that the universe is not an uncaused, eternal entity that “just is.” Decades of observations support the Big Bang theory – the idea that the universe had a beginning in a hot, dense state about 13.8 billion years ago now.tufts.edu. As a Tufts University summary puts it, there is now “scientific consensus that our universe exploded into existence almost 14 billion years ago in an event known as the Big Bang.” now.tufts.edu Far from being “just there” forever, space, time, matter, and energy appear to have originated in a cosmic genesis event.

This Big Bang origin is not mere speculation; it’s grounded in multiple lines of empirical evidence. Edwin Hubble’s discovery of the expanding universe, the detection of the cosmic microwave background radiation, and the measured abundances of light elements all point to a universe that evolved from an initial singularity or very early high-energy state. The Big Bang “represents the creation event – the creation not only of all the matter and energy in the universe, but also of space-time itself,” explains physicist Paul Davies templeton.org. In other words, time and space themselves seem to have begun with the Big Bang. Such a finding is profoundly at odds with the idea that the universe simply exists inexplicably. If the universe had a beginning, it invites the question of what brought it into existence or why it began – a question Russell’s off-hand dismissal pointedly avoids.

Historically, scientists who (like Russell) were uncomfortable with a cosmic beginning tried to find ways around it. For example, proponents of the Steady State theory argued for an eternal universe with matter continuously created to fill the gaps from expansion. Yet one by one, these alternatives have been overturned by evidence. The Big Bang model has “passed every scientific test that physicists could subject it to,” succeeding where rival eternal-universe models failed. The more we learn about our cosmos, the more the evidence forces us to acknowledge a beginning. As cosmologist Alexander Vilenkin bluntly states, “cosmologists can no longer hide behind the possibility of a past-eternal universe. There is no escape: they have to face the problem of a cosmic beginning.” An eternal, “just there” universe is no longer scientifically tenable in light of modern discoveries.

The Borde–Guth–Vilenkin Theorem and the End of Eternal Cosmologies

It’s not just empirical observation that points to a beginning—deep theoretical results do as well. In 2003, physicists Arvind Borde, Alan Guth, and Alexander Vilenkin proved a remarkable theorem about cosmic origins. The Borde–Guth–Vilenkin (BGV) theorem shows that any universe which has, on average, been expanding throughout its history cannot be infinite in the past and must have a beginning. Importantly, this conclusion holds under very general conditions, without assuming any specific physical laws beyond basic expansion. In Vilenkin’s words, under reasonable assumptions “the universe must, in fact, have had a beginning.”

The power of the BGV theorem is that it applies even to speculative scenarios that tried to avoid a starting point. For example, one might imagine an eternal inflationary multiverse (endless generation of universes) or a cyclic universe that oscillates through infinite expansions and contractions. But Borde, Guth, and Vilenkin proved that even inflating universes are “past-incomplete” – i.e. they cannot be extended indefinitely into the past ar5iv.org. “Although inflation may be eternal in the future, it cannot be extended indefinitely to the past,” Vilenkin explains ar5iv.org. Similarly, a cyclic cosmology would face the accumulation of entropy with each cycle, requiring each cycle to be larger than the last; this leads to the same problem of an ultimate beginning point. In short, theoretical physics has failed to find a loophole that allows a universe to exist forever into the past. As a 2012 analysis by Mithani and Vilenkin concluded after examining several such models: “none of them can actually be eternal in the past.” All the scenarios “which seemed to offer a way to avoid a beginning” still end up having to begin. Their verdict was that “the answer to [whether the universe had a beginning] is probably yes.”

This has huge significance for Russell’s claim. If even in principle physics tells us the cosmos cannot be past-eternal, then the universe is not an inexplicable brute fact that existed for eternity. It had a starting point, which cries out for explanation. Russell’s quip “that’s all” glosses over what is actually a profound mystery: why did the universe begin when it did, and what caused it? Science does not answer those questions directly, but it sharply undercuts the complacency of refusing to even ask. The universe is not “just there” in a steady state; it had an onset, and very likely some cause or prior condition enabling that onset.

Thermodynamics and the Impossibility of an Eternal Universe

Another scientific line of reasoning supporting a cosmic beginning comes from thermodynamics, particularly the Second Law. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that entropy (disorder) in a closed system tends to increase or stay the same over time. Applied to the entire universe, this principle implies that over an infinitely long time, the universe would inexorably run down to a state of maximum entropy (often called heat death, where no work or life would be possible). If the universe were truly eternal in the past – if it had existed infinitely long “just there” – then it should have already reached heat death by now. The fact that we still observe usable energy, temperature differences, and complex structures means the universe has not approached thermal equilibrium yet. This strongly suggests the universe has not existed forever; it had a lower-entropy beginning a finite time ago.

In fact, 19th-century physicists realized this implication long before modern cosmology. Lord Kelvin formulated the “heat death paradox,” pointing out that an infinitely old universe contradicts the Second Law – in an eternal cosmos, entropy would have accumulated to a maximum, which is not what we see. As the historical record notes, Kelvin’s argument “disproves an infinitely old universe.” Modern cosmologists echo the same point: the known thermodynamic arrow of time makes an eternal, steady-state universe exceedingly hard to square with reality. The universe’s youth (in cosmic terms) and abundant free energy today testify that it has only been around for a finite duration.

Even proposals of an eternal cyclic universe run into entropy problems. With each cycle, entropy would carry over. Sir Roger Penrose, for instance, calculated that to avoid entropy buildup, any cyclic model must have extraordinary conditions (like universe expansion to dilute entropy) – effectively still requiring a kind of beginning or a special initial low-entropy state. We can thus say the entropy condition of the universe is another clue that the cosmos is not a brute fact existing eternally; it had an initial low-entropy state that begs for an explanation. Astrophysicist Paul Davies highlights the puzzle: “the universe has a very low entropy beginning – an incredibly special, highly ordered start”, which is something that calls for a reason, not a mere shrug.

Can the Universe Be a “Brute Fact” in Science?

Given that modern cosmology points toward a universe with a beginning, scientists and philosophers have grappled with what (if anything) caused the Big Bang. Some have attempted to argue that perhaps the universe could simply appear from “nothing” under the laws of quantum physics – essentially a spontaneous, uncaused event. For example, physicist Lawrence Krauss has suggested that quantum fluctuations might produce universes from a quantum vacuum state (which he misleadingly terms “nothing”). However, such proposals typically smuggle in the laws of physics or a pre-existing quantum realm as the background – so they don’t truly show the universe popping into being utterly without explanation. Moreover, even these exotic ideas acknowledge a mechanism (quantum tunneling, vacuum energy, etc.), which itself would require an explanation for why that mechanism exists. In short, they are not saying “the universe is just there” in the sense Russell meant; they are offering a kind of scientific cause, however speculative.

It’s telling that when faced with the evidence of a beginning, few scientists actually double down on “brute fact” without cause. The impulse of science is to seek some explanation. As Vilenkin notes, the beginning of the universe is a “problem” that cosmologists feel compelled to face. The brute-fact stance would effectively halt inquiry by saying “no explanation is possible or needed” – a move that is antithetical to the scientific spirit. Even proposals like a self-causing universe (where the universe’s existence is explained by an earlier phase of itself in a loop) are attempts to explain the existence of the universe, not deny the need for explanation. (Philosopher Daniel Dennett, for instance, mused that “the universe creates itself ex nihilo… out of something that is almost indistinguishable from nothing at all”, which, while rhetorically clever, is basically an admission that something is producing the universe, not that it exists with no cause templeton.org.)

The bottom line from the scientific perspective is this: Everything we have learned about cosmology in the last century undermines the idea of a static, uncaused universe. The universe began, and began in a highly ordered state under precise conditions. The natural question is “why?” To simply answer, as Russell did, that “it’s just there” is to fly in the face of both evidence and the scientific ethos of seeking deeper understanding. If scientists of earlier generations had accepted brute facts easily, they might never have discovered the Big Bang at all – they might have said “the universe just exists, no point in investigating its origin.” Fortunately, they did not. Instead, by treating the universe not as “that’s all” but as something whose origin could be understood, science was able to uncover profound truths about cosmic history. Thus, on scientific grounds, Russell’s claim looks not only implausible, but intellectually shortsighted.

Philosophical Refutation: Why “Brute Fact” Explanations Fail

Contingency and the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR)

Russell’s stance that the universe requires no explanation clashes with a long tradition in philosophy that insists everything contingent must have a reason or cause. The universe is generally regarded as a contingent reality – it didn’t have to exist, and it could have been otherwise (with different properties, or no universe at all). It is not a self-evidently necessary being or an analytic truth. Philosophers from antiquity to the present have argued that it is improper to simply posit a contingent thing’s existence as a brute fact. This intuition is captured in the Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR), classically formulated by Leibniz, which in one form states: “For every existing thing or true fact, there must be an adequate explanation for why it is so and not otherwise.” In plainer terms, the PSR says nothing just exists without a reason – there are no brute facts.

The roots of this principle go deep. The pre-Socratic philosopher Parmenides, for example, implicitly invoked it when he argued that the world could not have simply popped into existence from nothing. If it did, we could always ask “why did it come into being at this moment rather than earlier or later?” – and with nothing before it, no answer could be given. Such a creation from nothing would be an “arbitrary brute fact,” which Parmenides found unacceptable. He thus concluded that the world did not come into existence from nothing without cause. This is an early philosophical rejection of exactly the sort of move Russell makes. Likewise, Leibniz in the 17th century famously asked “Why is there something rather than nothing?” and argued that the ultimate explanation must lie in a necessary being, since assuming the world is a brute fact would violate the PSR.

To say the universe is a brute fact is essentially to deny the PSR – to claim that at least one big thing (the existence of the material cosmos) has no explanation whatsoever. Many philosophers find this deeply problematic. Alexander Pruss, a contemporary philosopher who has written extensively on the PSR, notes that accepting brute facts outright would undercut our rational enterprise. He warns that “claiming [something] to be a brute fact should be a last resort. It would undercut the practice of science.” If we allow that the entire universe has no reason behind it, we’ve abandoned the principle that makes the universe intelligible. Robert Koons, another modern philosopher, likewise argues that the success of science and reason itself relies on the assumption that things are explicable rather than magical or arbitrary. In other words, the PSR isn’t just a dogma – it is woven into how we reason about the world. Every scientific discovery assumes that phenomena have explanations; every historical or cosmological theory assumes there is some cause or rationale. To exempt the universe as a whole from this and say “it just exists for no reason” is to take an exception of cosmic proportions, one that seems ad hoc and unjustified.

The Implausibility of an Uncaused, Contingent Universe

Treating the universe as a brute fact faces several conceptual difficulties. Let us consider a few key problems with Russell’s “just there, that’s all” stance:

- Arbitrariness and Lack of Explanation: Calling the universe a brute fact does not actually answer any question – it avoids the question. The existence of our universe (with its specific laws, constants, and contents) is extraordinarily specific. Why this universe and not nothing? Why these laws and not different ones? To say “it just is” is to leave all of those “why” questions utterly unanswered. It makes the existence of the universe a fundamentally arbitrary occurrence. But a truly arbitrary, unexplained contingency undermines our expectation that reality has some rational order. As one commentator put it in critiquing Russell, “the fact that there are and have always been dependent beings” having no explanation at all seems deeply unsatisfying as a final answer. We naturally feel that being is not a flip of a coin that might just as well have come up “nothingness.”

- Undermining of Reason and Science: As Pruss and Koons observed, to accept brute facts at the fundamental level is a “last resort” because it cuts against the grain of reason. If the universe as a whole had no reason, then in principle anything could just exist for no reason. It would be as if a vast unexplained accident lay at the heart of reality. This stance offers no predictive power and no understanding; it effectively tells us to stop asking questions. In practice, neither science nor everyday reasoning operates like this. We don’t assume events or things have no cause unless forced. Thus, labeling the entire cosmos (the most significant “event” of all, one might say) as causeless is an extreme position that many thinkers see as intellectually lazy or even self-defeating. After all, if we truly believed brute facts can just exist, one might wonder why we bother investigating anything – maybe each thing “just is.” The success of science suggests the opposite: digging deeper does reveal explanations. It’s reasonable to think the same about existence itself.

- Infinite Regress and Explanatory Failure: Russell in his debate with Copleston suggested that if every component of the universe has a cause or explanation, that’s enough – the universe in total needs no further cause (he accused his opponent of a “fallacy of composition”). But many philosophers have countered that even an infinite regress of explanations for individual parts still fails to explain the existence of the whole set. Imagine, for instance, an infinite chain of dominos falling, or an infinite series of eggs and chickens each produced by a prior one. You can explain each item by the previous one, but the entire infinite chain is left without a reason for existing at all. As Pruss humorously illustrates, an “infinite chicken-and-egg regress” still wouldn’t explain why any chicken (or egg) exists in the first place. If the universe had an infinite past with each state caused by a previous state, we still wouldn’t have answered “Why is there this eternal universe and not nothing?” The existence of an infinite series of contingent events is itself contingent, not logically necessary – it could have been otherwise (no series at all). So pointing to an infinite regress (even if it were possible) doesn’t avoid the need for a sufficient reason; it merely pushes it back without ever answering it. Russell’s brute-fact claim thus leaves a gaping explanatory gap.

- The Universe’s Contingency: Some philosophers sympathetic to Russell have suggested that perhaps the universe (or multiverse) is itself a necessary being, so that it isn’t contingent at all – it exists by a necessity of its own nature, just as some theists claim God exists necessarily. If that were true, the universe wouldn’t need a cause (because necessary beings are self-explained by their very nature). However, this move is widely seen as implausible. The universe does not exhibit the hallmarks of a necessary being. We can conceive of it not existing; there is no logical contradiction in imagining no material world at all (whereas a true necessary being must exist in all possible realities). The laws of physics, as we know them, could have been different – they are not fixed by logic alone. Saying the universe must exist just as it is would be an immense stretch. As philosopher Bede Rundle (whom Russell’s view aligns with) noted, to treat the universe as the “brute fact of reality” basically means declaring it to be inexplicably necessary. But that is arguably just giving a fancy name (“necessary”) to our ignorance. In absence of a logical proof that the universe could not fail to exist, labeling it necessary is unwarranted. It remains a contingent thing whose existence calls for explanation.

- “Anything Goes” Problem: If one permits brute facts, one faces a troubling arbitrariness: why stop at just one brute fact? If the entire universe can exist for no reason, in principle we could have countless unexplained things. One might say “well, universes just pop into being uncaused sometimes.” If that’s true, why don’t we see new universes (or other entities) popping into existence uncaused within our reality? Typically, the reply is “the universe is a unique case.” But this special pleading only underscores that treating the universe as an exception to the rule of explanation is not grounded in anything except a desire to avoid an ultimate cause. It’s a move of desperation, not a principled philosophical stance. Philosopher Alexander Pruss points out that the PSR – the rejection of brute facts – has a great strength: it doesn’t allow arbitrary limits or unexplained coincidences, thereby making reality more coherent. Abandoning it for the universe opens the door to chaos in our understanding: if one miracle (uncaused universe) is allowed, what principle forbids others? Thus, rational coherence favors no brute facts at all.

In light of these issues, the “universe is just there” assertion appears exceedingly weak. It isn’t an explanation; it’s a refusal to seek an explanation. Copleston, in the 1948 debate, pressed Russell on this very point: to say the universe has no explanation is to give up the search for understanding the most important question of all. It’s worth noting that Russell’s own stance may have been influenced by the scientific climate of his time (the Big Bang theory was not yet confirmed in 1948, and an eternal universe still seemed scientifically plausible to many). But today, with a cosmic beginning strongly supported, the brute-fact claim has even less appeal – it flies in the face of both reason and evidence.

Contemporary Philosophers Weigh In

A number of modern philosophers have developed rigorous arguments to show that Russell’s brute-fact position is untenable. We have already mentioned Alexander Pruss and Robert Koons, who both defend versions of the cosmological argument (the argument that the cosmos must have an ultimate cause or reason). Pruss in his The Principle of Sufficient Reason (2006) contends that denying the PSR leads to a collapse of explanatory frameworks; he famously wrote that if we ever have to accept a brute fact, it should be only as a last resort because doing so undermines the very rationality of inquiry. Koons, in a seminal 1997 paper, argued that even the possibility of an infinite regress of causes does not remove the need for a fundamental explanation — he uses tools from logic and mereology to show that the collection of all contingent facts itself must have a cause, otherwise we are left with something unexplained by definition. Both philosophers highlight that the success of science in explaining natural phenomena is a strong motivator to think reality is ultimately explicable. Accepting an unexplained universe, in their view, would be an arbitrary cutoff in the search for truth.

Other contemporary thinkers have echoed these sentiments. Philosopher Alexander Rasmussen and others have revisited the classic Leibnizian cosmological argument, updating it with modern modal logic to argue that there must be a necessary foundation to reality (often construed as a necessary being or an initial cause), because an endless series of contingent things or a giant contingent fact cannot adequately ground its own existence. On the other side, philosophers who are more sympathetic to the brute fact view (such as Graham Oppy or Bede Rundle) acknowledge that their position comes at a cost: it leaves the existence of the universe as an ultimate mystery. They essentially bite the bullet and accept that perhaps reality is absurd at the base – but even they grant that this is not a satisfying explanation, just the only one they see as compatible with a naturalistic worldview. In a way, this concession shows the persuasive power of the critiques: the brute fact stance wins by default only if every explanatory avenue is blocked. But as we’ve seen, science and philosophy provide several avenues suggesting the universe is not a causeless, inexplicable object.

It’s instructive to compare the brute fact of a contingent universe to the alternative explanation often proposed: a necessary, transcendent cause (for example, God in classical theism). Critics like Russell sometimes retort, “Well, if everything must have an explanation, what about God? Isn’t God then a brute fact?” The classical answer is that God (or any proposed necessary being) is not a contingent thing at all – by definition a necessary being exists by its own nature and cannot not exist, so it doesn’t require an external explanation. One might or might not accept that such a being exists, but the concept is categorically different from a brute contingent fact. The universe, as discussed, doesn’t appear to have the qualities of necessity (it could conceivably not exist or be different), so invoking a necessary being as the terminus of explanation is seen by these philosophers as more plausible than halting explanation arbitrarily at the universe. In short, saying “God exists unexplained” is not the same as “a contingent universe exists unexplained,” because the former is claimed to be self-explanatory (necessary) whereas the latter is not. Thus, the cosmological argument proponents maintain that Russell’s stance is actually less rationally satisfying than the alternative he rejected, since at least the alternative endeavors to explain existence by something ultimate rather than treating existence itself as a fluke.

Conclusion: The Universe Isn’t “Just There”

Both modern science and philosophy converge on the view that Russell’s throwaway line – “the universe is just there, and that’s all” – fails as an adequate answer. Scientifically, we have strong reasons to think the universe had a beginning and thus is not an eternal, inexplicable given. The Big Bang and subsequent cosmological findings have posed the question of origins sharply, and even theoretical physics arguments like the BGV theorem reinforce that a “past-eternal” universe (the kind that could more easily be treated as a brute fact) is implausible. Philosophically, declaring the universe a brute fact runs against the Principle of Sufficient Reason, a principle which underlies rational inquiry and which thinkers from Parmenides to Pruss have defended. It faces the problems of arbitrariness, incompleteness, and intellectual unsatisfactoriness. In a slightly persuasive spirit, we can say: Russell’s stance attempts to cut off a line of questioning – “Why is there a universe at all?” – that human reason naturally wants to pursue. But neither our contemporary knowledge nor our philosophical tools give us any good reason to grant such an exemption to the universe.

Far from showing the strength of Russell’s position, our exploration has highlighted its weakness. It amounts to saying, “one gigantic miracle exists for no reason – and that’s the end of it.” For anyone committed to a coherent, logical worldview, this should be a last ditch move, not a first response. The universe calls for explanation just as much as any phenomenon within the universe does. In fact, it calls for it even more urgently, being the totality of contingent reality. Thus, both scientifically and philosophically, we find Russell’s claim implausible. The universe is not “just there” – it demands an explanation, and refusing to acknowledge that demand does not make it go away. As our knowledge advances, the universe looks ever less like an inexplicable brute fact and ever more like something that had a cause or reason beyond itself. In the grand quest for understanding “why there is something rather than nothing,” simply saying “that’s all” is not a satisfying answer – and it likely never will be.

Sources:

- Jacqueline Mitchell, Tufts Now – “What Happened Before the Big Bang?” (2012) now.tufts.edu

- Audrey Mithani & Alexander Vilenkin – Did the universe have a beginning? (2012) ar5iv.orgar5iv.org

- Alexander Vilenkin, quoted in John Templeton Foundation – “The Resurrection of Cosmological Logic” (2020) templeton.org

- Wikipedia – “Heat death of the universe” (entry on thermodynamic paradox) en.wikipedia.org

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Principle of Sufficient Reason” (2020) plato.stanford.edu

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Cosmological Argument” (2018) plato.stanford.edu

Leave a reply to Nature’s Testimony in the Qur’an: Quranic Oaths, Divine Truth, and the Role of Science – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply