Epigraph

In the name of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy. Say, ‘He is God the One, God the eternal. He begot no one nor was He begotten. No one is comparable to Him.’ (Surah Al Ikhlas of the Quran, which is metaphorically one third of the Glorious Quran)

Written and Collected by Zia H Shah, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Introduction

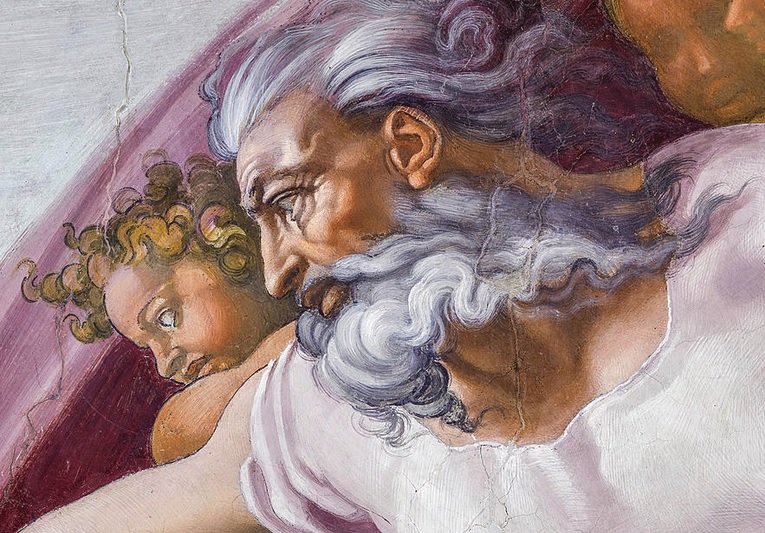

Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, completed in 1512, famously include anthropomorphic depictions of God – most notably in the Creation of Adam, where God is portrayed as an elderly, bearded man reaching out to spark life in Adam. This vivid portrayal raises a provocative question: does such imagery conflict with the Second Commandment’s prohibition of “graven images”? The Second Commandment, found in Exodus 20:4–5, states: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath…; you shall not bow down to them or serve them.” catholic.com. This article will analyze the Sistine Chapel’s anthropomorphic image of God in light of that commandment, comparing Catholic and Protestant interpretations and exploring the historical theological debate about images, iconography, and idolatry.

The Second Commandment in Scripture

In its original context, the Second Commandment clearly forbids the creation of idols or images for the purpose of worship. Coming as part of Israel’s covenant law, it was a response to the rampant idolatry in the ancient Near East. The commandment specifically bans making any likeness of things in heaven or earth as objects of devotion (Exodus 20:4-5) catholic.com. The concern was that people might “bow down to them or serve them,” thus diverting worship from the one true God to created images. Biblical history underscores this intent: for example, when the Israelites worshipped the golden calf, they were punished not for crafting art per se, but for worshiping the calf as if it were God (Exodus 32). In Deuteronomy, Moses also emphasizes that Israel saw “no form” of God at Sinai, warning them not to corrupt themselves by making a carved image vatican.va. Thus, the core of the commandment is a prohibition against idolatry – against worshiping false gods or even trying to worship the true God in the wrong way via man-made representations. All major Christian traditions agree that worshiping an image as God is a grave sin of idolatry. However, they have long differed on whether merely making or using religious images (without idolizing them) is permissible. This difference in interpretation lies at the heart of whether Michelangelo’s portrayal of God on the Sistine ceiling would be seen as a violation or not.

Anthropomorphic Imagery on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling

On the Sistine Chapel ceiling, Michelangelo rendered God in a strikingly human form. In the Creation of Adam panel, God is depicted as a vigorous older man draped in flowing robes, extending his hand toward the reclining Adam. Adam mirrors the gesture with his own hand, in a composition that nearly brings their fingertips to touching. This bold anthropomorphic portrayal of the Creator is visually powerful. Rather than depicting God as an abstract symbol or merely as divine light, Michelangelo chose to humanize God’s form. Art historians note that this “dynamic and human-like” depiction of God – muscular, fatherly, and intimately engaged with humanity – “emphasizes the intimate connection between the divine and the human” theartofstitch.com. The fresco captures the theological concept of humans being created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) by literally mirroring Adam’s physique to God’s. Michelangelo’s artistic choice here was revolutionary for its time theartofstitch.com, making the unseen God dramatically visible and personal.

However, it is exactly this making God visible that raises theological eyebrows. The Second Commandment forbids making any likeness of anything “in heaven above” to worship, and surely God Himself is “in heaven above.” Does portraying God the Father as a man – even if the intent is to honor the biblical creation story – cross a line into forbidden territory? Michelangelo’s contemporaries in the Catholic Church evidently did not think so; the fresco was commissioned and approved by Pope Julius II and later Popes. Yet, in other branches of Christianity (and even for some within Catholicism), depicting God in human form treads on delicate ground. Historically, Christian artists had often been cautious about portraying God the Father directly. Early Christian art, for instance, never showed God as a literal figure; at most, a hand reaching down from heaven would symbolize God. By the Renaissance, portrayals of God the Father as an old man (inspired in part by biblical language about the “Ancient of Days” in Daniel 7:9) had become more accepted in Western art. Michelangelo’s ceiling took this to new heights of prominence. The question is whether this powerful artwork is a profound teaching tool and inspiration, or an improper “graven image.” The answer has differed markedly between Catholic and Protestant theology.

Catholic Interpretation: Sacred Images as Veneration, Not Idolatry

The Catholic Church’s long-held position is that religious images, when used properly, do not violate the Second Commandment. The prohibition in Exodus is understood to forbid the worship of images as gods, but not the mere creation or use of imagery in worship of the true God. Catholics point out that God Himself, at certain times, commanded or allowed images that served a religious purpose. For example, God instructed Moses to make a bronze serpent and raise it on a pole for the people to look at and be healed (Numbers 21:8-9). He likewise commanded gilded statues of cherubim (angels) on the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:18-20) and later gave plans for Solomon’s Temple adorned with carved figures (1 Kings 6:23-29) catholicnewsagency.com. These instances suggest that the mere making of religious images was not inherently wrong; what was condemned was the idolizing of them (indeed, when the bronze serpent later became an object of worship, King Hezekiah had it destroyed – 2 Kings 18:4).

By the early centuries of the Church, a tradition of sacred art began to flourish, depicting Christ, Mary, and biblical scenes. This provoked debate about idolatry, reaching a flashpoint in the 8th century during the Iconoclast Controversy in the Eastern Church. Byzantine Emperor Leo III banned religious images as violating the Second Commandment, sparking a decades-long conflict folgerpedia.folger.edu. The issue was resolved at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which affirmed the propriety of holy images. This Council drew an important distinction between worship and veneration: latria, the adoration due to God alone, versus dulia, the honor given to saints or sacred images folgerpedia.folger.edu. The council taught that venerating an image of Christ or a saint does not mean one is worshiping the image itself. Rather, “the honor rendered to an image passes to its prototype”, as Church Fathers like St. Basil had explained vatican.va. In other words, when a Christian shows reverence toward a crucifix or a painting of God, the true recipient of that honor is the person represented (Christ, or God Himself), not the wood or paint. The Catechism of the Catholic Church reiterates this, stating: “The Christian veneration of images is not contrary to the first commandment which proscribes idols… the honor paid to sacred images is a respectful veneration, not the adoration due to God alone” vatican.va.

During the Protestant Reformation, as we will see, Catholics found it necessary to defend this position with even greater clarity. The Council of Trent (1545–1563), responding to Protestant iconoclasm, reaffirmed the use of images in worship. In its 25th session the council declared that “the images of Christ, and of the Virgin Mother of God, and of the saints are to be had and retained particularly in churches, and due honor and veneration are to be given them; not that any divinity or virtue is believed to be in them… but because the honor which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent.” catholicnewsagency.com In short, the Catholic Church condemned idolatria (idol-worship) in the strongest terms – it was listed among the gravest sins. But it maintained that sacred art is not idolatry when used to uplift the mind to the realities of God and the saints. Images were seen as educational and devotional aids – the “Bible of the poor,” as the saying went, allowing even the illiterate to contemplate the mysteries of the faith folgerpedia.folger.edu. A pious Catholic gazing at Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam is not praying to that painted figure of God as though the plaster were God; rather, the painting serves as a window to the divine, inspiring the viewer to worship the real God whom it depicts. From the Catholic perspective, then, Michelangelo’s anthropomorphic rendering of God on the Sistine ceiling does not violate the Second Commandment, because it is not meant to be worshipped as an idol. It is a portrayal meant to teach and inspire – a legitimate form of veneration of God through art, rooted in the doctrine of the Incarnation (the Son of God taking visible, human form) which opened the way to representing God in visual form vatican.va.

Protestant Perspectives: Iconoclasm and Idolatry

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century sharply diverged from Catholic tradition on the issue of images. Many Reformers believed that the Catholic use of images in churches had crossed into idolatry, or at least posed an ever-present temptation to violate the Second Commandment. They read the commandment in Exodus 20:4–5 as a blanket ban against making any representation of divine realities for use in worship. In their view, God’s command “You shall not make for yourself any carved image or likeness of anything…” was not limited to pagan idols, but encompassed attempts to depict the true God as well desiringgod.org. They feared that even if an image was intended to honor God, it could end up diluting His glory or becoming a focal point of false devotion. Reformer John Calvin argued that God’s infinite majesty cannot be adequately portrayed by finite images, and thus any portrayal of God inevitably distorts and diminishes the divine reality inallthings.org. He was emphatic that making images of God (including Christ) violates God’s command. In one of his sermons on Deuteronomy, Calvin asks rhetorically of paintings of Christ, “Is it not a wiping away of that which is chiefest in our Lord Jesus Christ – that is to wit, of his divine Majesty?” – answering yes inallthings.org. For Calvin and those in the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition, the Second Commandment was understood as instructing how God must be worshipped: namely, not by any physical images. Classic Reformed catechisms thus teach that the commandment forbids “the making any representation of God, of all or of any of the three persons” and the use of such images in worship desiringgod.org. As one 19th-century Protestant theologian put it, “Idolatry consists not only in the worship of false gods, but also in the worship of the true God by images.”

From this standpoint, using a painting – even a magnificent one like the Sistine Chapel’s – as an aid to worship the true God would be seen as a form of false worship. J.I. Packer, a well-known 20th-century Reformed theologian, echoed this view, writing that the Second Commandment “tells us not to make use of visual or pictorial representations of the triune God, or of any person of the Trinity, for the purposes of Christian worship… statues and pictures of the One whom we worship are not to be used as an aid to worshiping him.”

In such a strict interpretation, Michelangelo’s portrayal of God the Father on the Sistine ceiling is problematic not necessarily because the art exists, but because it is placed in a sacred space (a chapel) and could be used devotionally, thereby violating the intended meaning of the commandment.

It is important to note that not all Protestant leaders were equally strict on this issue. Martin Luther, for example, took a more permissive stance on religious art. He was wary of worshiping images, but he did not insist on purging all imagery from churches. In a debate with the more radical iconoclasts of his day, Luther argued that images could serve as useful “books” for the uneducated, illustrating biblical truths. He even contended that abolishing all images was an overreaction that bound people’s consciences unnecessarily inallthings.org. Nevertheless, the overall thrust of the Reformation, especially in Reformed (Calvinist), Puritan, and certain Anglican circles, was toward iconoclasm – the destruction or removal of images from places of worship. In Switzerland, Huldrych Zwingli and his followers whitewashed church walls and smashed statues, convinced that “the mere fabricating of an image for sacred use violates the 2nd commandment” inallthings.org. In England, during the reign of Edward VI and the Puritan movements, there was widespread removal of church images and stained glass, driven by the belief that they were idols folgerpedia.folger.edu. The Reformation era saw many statues decapitated and paintings torn down in the fury of zeal to uphold what Protestants saw as God’s clear command against graven images.

From the Protestant perspective that emphasizes sola Scriptura (Scripture alone), the explicit wording of the Second Commandment was given priority over the Church’s tradition of art. The use of lavish imagery like the Sistine Chapel ceiling could be seen as a human innovation not warranted by Scripture – or worse, as a direct contradiction of God’s word. Indeed, Protestant writers frequently pointed to such Catholic art as evidence of the Church’s deviation. An English Puritan tract of the 17th century condemned the Catholic veneration of images by quoting Exodus 20:4–6 and insisting that any such practice was blatant disobedience to God folgerpedia.folger.edu. To these reformers, Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, for all its beauty, would likely be viewed as a graven image in the Lord’s sanctuary – precisely what the Second Commandment intended to prevent.

Historical and Theological Reconciliation?

The clash between these viewpoints is rooted in differing understandings of the purpose of the Second Commandment. Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox Christians as well) focus on the intent behind images: if the intention and practice are to honor God and not to treat the image itself as a god, then no idolatry is committed. The physical image is a conduit for reverence to pass to the prototype (the reality depicted) catholicnewsagency.com vatican.va. Protestants, especially of the Reformed tradition, worry that images by their very nature can mislead the heart and obscure God’s glory, and that God’s commandment was a precautionary fence to prevent humans from attempting to contain the divine in man-made form desiringgod.org. There is also a Christological nuance: Catholics argue that because God took on a visible, material form in Jesus Christ, it sanctified the use of images – “the Son of God introduced a new economy of images” by becoming incarnate vatican.va. Many Protestants respond that while portraying Jesus’s humanity might be acceptable in theory (since He had a true human body), portraying the divine nature (or the Father and Holy Spirit who never became incarnate) remains off-limits. Michelangelo’s painting does not depict Christ’s human nature, but God the Father in human form – something Scripture never directly describes. This made such depictions especially objectionable to conservative Protestants, who saw them as speculative at best and blasphemous at worst.

Conclusion

So, does the Sistine Chapel’s anthropomorphic imagery violate the Second Commandment? The answer has been debated for centuries and ultimately depends on one’s theological perspective. From a Catholic point of view, Michelangelo’s portrayal of God as an old man creating Adam is a legitimate artistic expression that lifts the mind to divine truths. It is not an idol but an image that receives honor, which is directed to God Himself beyond the image catholicnewsagency.com. The painting is a visual theology – conveying God’s fatherly relationship to humanity – and is meant to inspire awe and faith, not to be worshipped in place of God. As long as viewers understand the distinction between Creator and creation, the fresco serves as a tool for devotion rather than a temptation to idolatry. On the other hand, from a Protestant (Reformed) standpoint, that very depiction is fraught with spiritual danger. They would argue that God’s commandment was meant to guard against any attempt to give physical form to Him, knowing human tendency to then venerate what is seen. In their eyes, however well-intentioned, Michelangelo’s anthropomorphic God could encourage people to imagine the Almighty in a limited, creaturely way – essentially “worshiping the true God by an image,” which they believe God forbade desiringgod.org. Some Protestants would even say the Sistine Chapel ceiling reflects how the Catholic Church drifted into what the Reformers labeled idolatry.

In the end, the Creation of Adam and the broader Sistine Chapel ceiling stand as a testament to the enduring tension in Christianity between the love of visual beauty and the concern for purity of worship. The ceiling’s grandeur has moved countless souls to ponder the mysteries of creation and the Creator. Yet it also continues to spark discussion about the bounds of religious imagery. This very debate has enriched Christian thought: it challenges believers to consider what it means to worship God “in spirit and truth” (John 4:24) while also engaging the God-given human senses and imagination. Michelangelo’s anthropomorphic imagery sits at the crossroads of art and theology in Christianity, inviting viewers to encounter God visually – a prospect both inspiring and, to many, troubling. Whether one sees the Sistine Chapel’s imagery as a graven image or a great catechetical masterpiece, its impact on faith and art is undeniable. And as history shows, the interpretation of the Second Commandment will continue to inform how we view such images of the divine.

One thing is obvious: the Muslims and the Jews will continue to take strong exception to this art form.

From my perspective God represented as an old man also challenges the divinity of Jesus and Trinity, who was crucified as a young man.

Leave a reply to Zia H Shah Cancel reply