Epigraph

وَنَفْسٍ وَمَا سَوَّاهَا

فَأَلْهَمَهَا فُجُورَهَا وَتَقْوَاهَا

قَدْ أَفْلَحَ مَن زَكَّاهَا

وَقَدْ خَابَ مَن دَسَّاهَا

And the soul and its perfect proportioning.

He revealed to it the right and wrong of everything,

he indeed prospers who purifies it,

and he is ruined who corrupts it. (Al Quran 91:7-10)

Philosophical Perspective

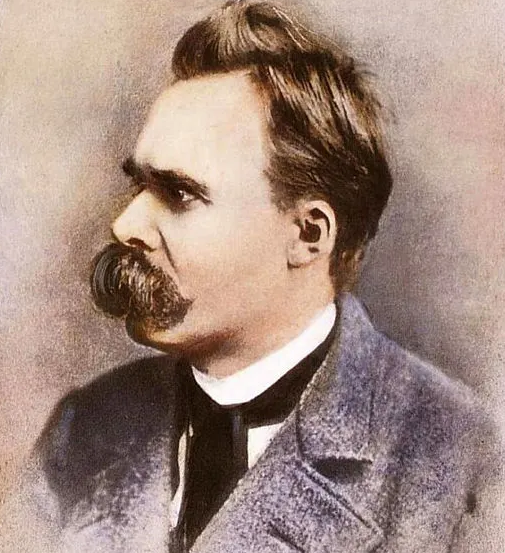

Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous quote is rooted in his broader philosophical outlook on nihilism, morality, and the human condition. In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), where this aphorism appears, Nietzsche warns that one must take care not to become what one opposes. The full passage reads: “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” The “abyss” here is a powerful metaphor for the void of meaninglessness and chaos – essentially Nietzsche’s concept of nihilism, the belief that life has no inherent meaning or values. Nietzsche foresaw that with the “death of God” (the collapse of traditional religious morality), European culture would face an existential void – “a vacuum of meaning” that could lead to despair and nihilism. In this sense, gazing into the abyss represents delving into extreme meaninglessness, suffering, or moral darkness. Nietzsche suggests that if one stares too long into this void – pondering emptiness or combating moral evil obsessively – that void will start to shape and transform the gazer. As one commentary puts it, “when individuals or societies engage in a prolonged struggle against evil… they risk adopting the very traits they are fighting against.”

In other words, the abyss “gazes back,” pulling the watcher into its own nihilistic, destructive perspective.

This idea fits into Nietzsche’s existential challenge: how to confront life’s inherent suffering and absence of absolute meaning without losing oneself. Nietzsche was not simply endorsing despair; rather, he believed we must overcome the abyss of nihilism. He introduced the concept of the Übermensch (overman/superman) and the will to power as responses to nihilism. The Übermensch is one who can face the death of old values and the abyss of meaninglessness yet create new values and affirm life. Nietzsche described this figure as “one who is not afraid to gaze into the abyss, [and] who after going through nihilism, overcomes it and affirms life.”

In other words, the ideal is to confront the abyss without being destroyed by it – to give the abyss meaning rather than let it drag you into meaninglessness. This is an expression of Nietzsche’s will to power, the creative drive to impose meaning and order on a chaotic world. The quote thus reflects a key tension in Nietzsche’s philosophy: one must bravely confront darkness and “fight monsters” (challenge false values, injustice, etc.), but do so with such self-mastery and creative force that one does not become monstrous or nihilistic in the process. The abyss can symbolize any profound moral or existential challenge – suffering, evil, inner emptiness – and Nietzsche’s broader message is that we must grapple with these challenges carefully. His stance is often seen as a precursor to existentialism: he recognized the abyss of a godless world and urged humanity to craft its own meaning (through the will to power) rather than fall prey to that abyss. If one instead fixates on the void – endlessly dwelling on life’s lack of inherent meaning or on the world’s evils – one risks internalizing that void. In sum, Nietzsche’s proverb is a philosophical warning about nihilism: stare too deeply into nothingness or evil, and it will stare back – meaning you may become nothing (morally bankrupt or despairing) or evil yourself. The antidote, in Nietzsche’s view, was to rise “beyond good and evil,” creating affirmative values and maintaining one’s psychological integrity even while acknowledging the abyss.

Psychological Perspective

Psychologically, Nietzsche’s warning captures the very real effect that prolonged engagement with darkness or negativity can have on a person’s mind and character. Modern psychology offers insights that align strikingly with Nietzsche’s point. For example, research on rumination and negativity shows that continually focusing on negative thoughts or experiences can distort one’s mindset and lead to depression or anxiety: “rumination is a mechanism that develops and sustains psychopathological conditions such as anxiety and depression.”

In everyday terms, “when we focus too much on negativity or darkness… we risk becoming like what we are staring at.”

If someone obsesses over trauma, injustice, or cynical thoughts (in Nietzsche’s metaphor, gazing into the abyss), those dark thoughts begin to “affect who we are,” potentially making the person more pessimistic, hostile, or numb. In this way, the “abyss gazes into you” can be seen as psychological transformation: the darkness you study or fight can infiltrate your own psyche.

There are many examples of this phenomenon. Consider someone who works with tragedy or cruelty every day – for instance, a trauma therapist, a soldier, or a police officer. Without healthy coping strategies, they may experience vicarious trauma or a numbing of empathy: over time, exposure to violence and evil can deaden their spirit or even make them see enemies everywhere. A striking real-world illustration is how some soldiers, in fighting brutal wars, become habituated to violence and struggle to reconnect with ordinary life, sometimes exhibiting aggression or alienation as if part of the war’s darkness followed them home. In Nietzsche’s terms, they have gazed into the abyss of warfare and it “gazed back,” leaving a lasting mark on their psyche. Psychologists have also observed a tendency called “identification with the aggressor,” where victims of abuse may begin to adopt the very behaviors of their abusers as a defense mechanism. This is akin to becoming a monster while fighting monsters. Similarly, individuals who fixate on an enemy or injustice can become consumed by hatred. Nietzsche’s quote is often invoked as a caution that fighting hatred with hatred will only breed more of the same. Indeed, a Psychology Today article notes that hatred and intolerance can be “contagious” – “contact with viral hatred can infect us,” eventually turning the well-intentioned hateful. Prolonged anger and hate corrupt one’s character, a literal case of the abyss of negativity taking hold of one’s inner life.

Furthermore, the quote speaks to moral psychology: a person who fixates on evil might start rationalizing unethical means. For instance, someone crusading to defeat a villain might start using villainous tactics themselves, believing “the ends justify the means.” This is a psychological slippery slope into what Nietzsche would call becoming a monster. Modern history and clinical experience both show how gradually one’s moral boundaries erode when one justifies ever more extreme responses to perceived evil. This is why Nietzsche’s aphorism resonates with psychologists’ advice to avoid obsessive negativity. Maintaining one’s moral compass and mental health requires stepping back from the abyss at times. In cognitive-behavioral terms, dwelling exclusively on negative thoughts can create a feedback loop – the gloom “stares back” by reinforcing depressive, cynical beliefs, which then seem more and more the only reality. Without interruption, this loop can lead to self-destruction or hopelessness. Nietzsche intuitively understood this danger: “Those who spend too much time contemplating this abyss risk becoming psychologically or spiritually consumed by it, losing their own sense of purpose or moral direction.”

In short, the aphorism highlights a profound psychological truth: we become what we behold. Prolonged exposure to darkness – whether internal or external – changes us, often in destructive ways, unless we consciously resist that pull. Nietzsche’s maxim thus anticipates the importance of self-awareness and mental balance when confronting one’s “inner demons” or external evils.

Literary and Historical Context

Nietzsche first published this quote in Beyond Good and Evil, Chapter 4 (Aphorism 146) in 1886. It comes at the end of a series of short aphorisms and is immediately preceded by the line about fighting with monsters. At the time, Nietzsche was critiquing conventional morality and warning against the self-corruption of moral crusaders. The line has since taken on a life of its own, deeply influencing literature, philosophy, and popular culture. It encapsulates a timeless theme: the danger of “becoming the thing you hate.” Many authors and creators, whether directly influenced by Nietzsche or not, have explored this idea. For example, in Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899), the character Kurtz ventures into the Congo with idealistic goals but gradually succumbs to the darkness (savagery and brutality) he encounters. Symbolically, he gazes into the “heart of darkness” and it gazes back – Kurtz becomes a horror himself, epitomized by his final words, “The horror! The horror!” Conrad’s tale thus mirrors Nietzsche’s warning about a moral abyss. Similarly, in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the creature Gollum is consumed by his long obsession with the Ring: in pursuing its power (and the evil within it), he loses his own identity and humanity. Literary tragic heroes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein also illustrate how an obsession (whether with power, revenge, or conquering death) can lead a character to ruin, essentially themselves becoming monstrous. This narrative arc – the avenger turned tyrant, or the idealist turned fanatic – has recurred throughout storytelling, showing the broad cultural resonance of “gazing into the abyss.”

In philosophy and intellectual history, Nietzsche’s idea influenced existentialist and postmodern thinkers who grappled with the problem of nihilism. Writers like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre, though not quoting Nietzsche’s line directly, address the same existential abyss. Camus, for instance, wrote of confronting the “absurd” – the inherent meaninglessness of life – but insisted on rebelling against it without succumbing to nihilism. This is essentially a response to the abyss: Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus can be read as advising, face the void but do not let it consume you. In psychology and ethics, the quote is often cited when discussing how good intentions can morph into harmful outcomes. It’s a staple in discussions of ethical paradoxes and corruption: for example, how revolutionaries can become dictators, or how zeal to stamp out a sin can breed fanaticism just as bad as the sin itself. The influence on popular culture is perhaps most visible through direct references. The quote (or variations of it) appears in countless books, movies, and games. For instance, in Christopher Nolan’s film The Dark Knight (2008), the character Harvey Dent pointedly says, “You either die a hero, or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.” This line is essentially a pop-culture rephrasing of Nietzsche’s aphorism – warning that a hero who fights evil for too long may transform into an evil-doer. Superhero and vigilante stories frequently play on this theme (characters like Batman grapple with how to fight criminals without adopting criminal methods). Even beyond explicit quotes, the notion of the abyss gazing back has become a trope: it’s common in fantasy or horror for a character studying dark magic or battling eldritch horrors to risk corruption by that very darkness. Nietzsche’s concise phrasing gave modern culture a memorable way to express this idea. Today, one might find the quote referenced in contexts ranging from political speeches to video games – it has become an “iconic quote” known widely, indicating how deeply Nietzsche’s insight has permeated our collective consciousness.

History itself unfortunately provides real examples of “gazing into the abyss” and having it gaze back. Nietzsche wrote in the 19th century, but the 20th century showed how societies fighting “monsters” could become monstrous. A clear case is the French Revolution. The revolutionaries set out to destroy tyranny and injustice (the “monsters” of the monarchy and inequality). Yet during the Reign of Terror (1793–94), the revolutionaries themselves, under Robespierre, instituted mass executions and acts of brutality shockingly similar to the oppression they opposed. In effect, by gazing into the abyss of violence and vengeance, they let it gaze back into them – the liberators became executioners. One historian noted that these revolutionaries justified monstrous actions in the name of high ideals, believing “there is no crime… that cannot be justified, provided it be committed in the name of an Ideal.”

This perfectly encapsulates Nietzsche’s caution: in pursuing an ideal (even a seemingly noble one), one can lose moral footing and commit atrocities. Another example is how the Allied powers in World War II, striving to defeat a monstrous evil (Nazism), resorted to morally troubling tactics like the firebombing of cities or the atomic bomb – raising enduring questions about becoming like the enemy one fights. In the Cold War, the United States famously worried about “not becoming the Soviet Union” in tactics; yet episodes like McCarthyism (hunting communist “monsters” with unjust methods) or the Vietnam War’s excesses showed the abyss staring back. More recently, in the aftermath of 9/11, U.S. leaders declared a war on terror – but by “working on the dark side” (to quote Vice President Dick Cheney) with torture and secret prisons, they arguably mirrored some of the inhumanity they aimed to eradicate. History is replete with such ironies: liberators becoming oppressors, defenders of morality engaging in torture, and idealists turning into fanatics. Nietzsche’s aphorism, therefore, has been used as a grim lens through which to view these events. It’s a reminder that good intentions must be wedded to self-awareness and restraint, or else we merely trade one abyss for another. As Nietzsche himself knew, even the project of rethinking morality (which he championed) carried risks – one must not abandon all restraint and “become a monster” in the process of overturning old values.

Modern Relevance

Nietzsche’s warning “gaze not into the abyss too long” is highly relevant to contemporary issues, often invoked in discussions of extremism, polarization, and personal morality today. In politics, we see a rise in extremism and polarization where each side demonizes the other as the “monster.” Nietzsche’s quote cautions all parties to take care: by vilifying one’s opponent absolutely, any group can start using the same hateful tactics and rhetoric that they condemn. For example, in the fight against extremist ideologies, some activists adopt extremist behavior themselves – responding to hate with hate. On social media and in public discourse, it’s common to see people justify vicious or dehumanizing language “because the other side is so terrible.” This is the abyss gazing back. The contagion of negativity that Nietzsche intimated is evident online: engaging incessantly with toxic content can breed toxicity in oneself. Mental health experts warn that social media outrage cycles can reinforce anger and fear, effectively pulling individuals into a negative mindset. As one psychologist noted during the pandemic’s online rancor, “hatred can infect us” and turning away from constant social media combat may be necessary to preserve one’s mental health. The essence of Nietzsche’s message is to remain vigilant about one’s own values and behavior, even when confronting something one righteously opposes. In a politically polarized world, this might mean refusing to engage in the same dehumanization or violence that one’s enemies do. It also speaks to moral dilemmas: for instance, how far should one go in fighting terrorism? If a nation uses torture or targets civilians to defeat a perceived evil, Nietzsche would imply that the nation has allowed the abyss to gaze back – it has sacrificed its moral character. The quote encourages a stance of principled balance: fight for what is right, but do not abandon compassion and ethics, or you “become a monster” indistinguishable from that which you fight.

On a personal level, the aphorism holds meaning for anyone grappling with their “inner darkness” or going through an existential crisis. Battling inner demons – be it addiction, anger, or despair – is often necessary for growth, but living in that headspace too long without relief can lead to self-destruction. For example, someone trying to overcome personal trauma must face painful memories (their abyss) to heal, but if they dwell endlessly on those memories without also seeking joy or support, they may find the trauma defining their entire identity. The phrase “staring into the abyss” is commonly used today to describe moments of deep existential dread or depression. Nietzsche’s follow-up “the abyss also gazes into you” is a poignant reminder to practice self-care and self-awareness in those moments. It underscores the importance of not losing oneself while confronting tough questions like “What is the meaning of my life?” or “Why do I suffer?”. In practical terms, this could mean that while you might reflect on life’s lack of obvious meaning (a classic existential abyss), you should balance it by finding personal sources of meaning – creativity, relationships, goals – so that the void doesn’t consume you. The concept of balance is key. As one interpretation notes, “Nietzsche was warning against allowing this to happen… People should be careful not to lose themselves in the process of confronting difficult situations. It’s essential to maintain balance and not let the ‘abyss’ take over.”

. This might involve taking breaks from negativity, cultivating positive experiences, or reminding oneself why one is fighting in the first place. In modern therapy-speak, it’s about not getting stuck in the darkness (don’t let a temporary gaze become a permanent stare).

We can also apply the quote to the phenomenon of ideological radicalization in contemporary society. Whether one looks at certain internet subcultures, political movements, or even cults, a pattern emerges: an individual begins by exploring an “abyss” – perhaps watching videos about society’s ills or engaging in extremist forums out of curiosity or outrage – and over time those very influences can radicalize the individual. They start to reflect the echo chamber they are in; the abyss of conspiracy theories or hate “gazes back” and they emerge with a transformed (more extreme) identity. This is why commentators across the political spectrum cite Nietzsche’s line as a warning about fighting fire with fire. For instance, those combating misinformation have to be careful not to become ideologues themselves; activists for justice have to mind that in fighting oppressors they don’t adopt oppressive tendencies. The quote’s modern significance lies in its call for self-reflection: when you’re battling evil or immersing yourself in darkness, continually check that you’re not absorbing that evil. Nietzsche challenges us to retain our humanity and moral vision even in the bleakest struggles. Thus, in contexts from combating terrorism and political hatred to dealing with personal trauma, “gazing into the abyss” remains a vivid metaphor. It urges moderation and mindfulness: engage with darkness enough to understand and overcome it, but not so much that it engulfs you.

Examples and Key Quotes

To further illustrate Nietzsche’s warning, it’s helpful to look at concrete examples and related passages from his work:

- Literature and Pop Culture: As discussed, many stories echo the “abyss” theme. One example is George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945), where the pigs lead a revolution to overthrow a cruel farmer (the monster), but eventually become indistinguishable from the tyrants they replaced. By the novel’s end, the liberators have become oppressors – a direct parallel to “the abyss gazes into you.” In modern pop culture, the trope is common in superhero narratives. For instance, Marvel’s Avengers films and other comic book adaptations often show heroes tempted to cross moral lines to defeat villains. The quote itself has been explicitly cited in video games and comics. The Batman franchise, as mentioned, frequently grapples with this: Batman risks becoming as violent and lawless as the criminals he fights. In the graphic novel Watchmen by Alan Moore, vigilante Rorschach’s unyielding war on crime turns him into a grim, almost sociopathic figure – he “gazes into the abyss” of human depravity so deeply that it warps his personality. These examples underscore how deeply Nietzsche’s idea has penetrated storytelling. When we see a character struggle not to be “consumed by the dark side” (to use Star Wars terminology), we are essentially revisiting Nietzsche’s insight. Even without knowing it, audiences understand the caution: we applaud heroes who defeat monsters without surrendering their honor or mercy.

- Historical Figures: History provides sobering real-world examples. Maximilien Robespierre, mentioned earlier, went from being an idealistic champion of liberty in the French Revolution to presiding over the Reign of Terror, executing thousands in the name of virtue. He is often cited as an example of someone who became the monster he fought against. Similarly, Joseph Stalin started as a revolutionary against the oppressive Tsarist regime, but once in power, he oversaw purges and labor camps that killed millions – effectively gazing into the abyss of absolute power and terror, and becoming a tyrant arguably worse than the one he replaced. On the flip side, we can consider leaders who were aware of this danger: Nelson Mandela, for example, after fighting the monstrosity of apartheid for decades, deliberately chose reconciliation over revenge when he gained power, famously warning that to pursue vengeance would doom South Africa to become what they hated. His approach implicitly heeds Nietzsche’s warning, showing that the abyss need not gaze back if one consciously resists that pull. Societies that have faced cycles of violence – say, communities torn by sectarian conflict – have learned that without deliberate efforts at peace and forgiveness, each side becomes a mirror of the other’s hatred (each side’s “monsters” breeding monstrosity in return). Nietzsche’s quote thus serves as a timeless commentary on the cycle of violence: brutality begets brutality, unless someone breaks the chain.

- Nietzsche’s Own Passages: Nietzsche returned to the imagery of the abyss and the challenge of overcoming nihilism in several works. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he uses the striking image: “Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman – a rope over an abyss.” Here, the abyss symbolizes the perilous gulf over which humanity is suspended – the risk of falling into meaninglessness as we evolve beyond old values. This metaphor complements the idea in the abyss quote: life’s journey toward higher goals is dangerous, and one can fall into the chasm of despair or evil at any time. Another key passage comes from On the Genealogy of Morals, where Nietzsche writes, “Man would rather will nothingness than not will at all.” This sentence illuminates why people end up embracing the “abyss.” Nietzsche suggests that if people cannot find positive meaning, they will choose negative meaning (“nothingness” ) over feeling purposeless. In other words, someone who gazes into the abyss of meaninglessness for too long might decide to become the abyss (choosing destruction, chaos, or fanaticism) simply to have something to live for. This powerful psychological insight—that humans crave meaning so much that they’ll take even destructive purpose over no purpose—sheds light on the abyss quote. It explains, for example, why a principled person might gradually slide into nihilism: lacking a constructive cause, they begin to identify with the void. Nietzsche’s work is full of such warnings about how easily noble intentions can curdle into their opposite. In Beyond Good and Evil itself, just a few sections after the abyss aphorism, Nietzsche notes how “madness is something rare in individuals — but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs it is the rule.” This aphorism resonates with the idea that when people come together under an extreme ideology (staring collectively into an ideological abyss), the madness normalizes and engulfs them en masse. It’s another way of saying that entire societies can “become monsters” when they lose sight of moderation.

To conclude, Nietzsche’s quote “And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you” endures as a succinct wisdom teaching on multiple levels. Philosophically, it’s about the temptation of nihilism and the need to create meaning lest meaninglessness consume us. Psychologically, it highlights the transformative impact of obsessive negativity or evil on the self. Its literary, cultural, and historical echoes reinforce how ubiquitous this pattern is – from tragic heroes and villains, to real revolutions and wars. And in our modern lives, the quote is a call for self-awareness: to check that in confronting darkness (whether in society or in our soul) we do not let it nest in us. Nietzsche, ever the diagnostician of the human spirit, is reminding us that moral integrity and mental balance are hard-won – especially when one dances on the edge of the abyss. The abyss may never disappear (there will always be suffering, evil, and uncertainty in life), but Nietzsche’s broader philosophy urges us to face it, without blinking, yet also without surrendering to it. In practical terms: fight your monsters, but hold onto yourself; explore the darkness, but carry a light. That is the only way the abyss will not stare back into us.

Sources:

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146 (1886) en.wikiquote.org.

- Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Prologue (1883) websites.nku.edu.

- Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, Third Essay, §28 (1887) goodreads.com.

- Inside Higher Ed – “Nietzsche’s ideas still resonate…” (Steven Mintz, 2024) – analysis of Nietzsche’s quote and its implications insidehighered.cominsidehighered.com.

- Sociology Learners – “Friedrich Nietzsche Philosophy of abyss” (2024) – accessible explanation of the quote sociologylearners.com.

- Eternalised Blog – “Nihilism – Friedrich Nietzsche’s Warning to the World” (2021) eternalisedofficial.com.

- City Journal – “Why Robespierre Chose Terror” (2019) – historical account of the Reign of Terror’s logic city-journal.org.

- Brad Reedy, Ph.D., Psychology Today – “Uncommon Sense in Uncommon Times” (2020) – on social media hatred as an abyss psychologytoday.com.

- Wikipedia – “Rumination (psychology)” – on negative thought cycles en.wikipedia.org.

Leave a comment