Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

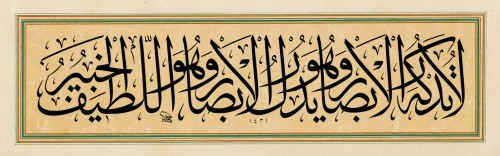

Quran 6:103 states: “No human vision can encompass Him, whereas He encompasses all human vision: for He alone is unfathomable, all-aware.”

Before we go into a commentary, I want to highlight some of its translations from a website that has collected more than 50 different English translations of the Quran:

“No powers of vision can comprehend Him, while He comprehends [all] vision; He is the Subtle, the Informed.” TB Irving

“Sight comprehends Him not, but He comprehends all sight. And He is the Subtle, the Aware.” The Study Quran

“No human vision can encompass Him, whereas He encompasses all human vision: for He alone is unfathomable, all-aware.” Muhammad Asad.

“The eyes comprehend Him not while He comprehends the sights. And He is the Keenest Observer, the Most Well-informed.” Dr. Kamal Omar

This verse succinctly expresses the transcendence of God (Allah) and the limitations of human perception. Below, we explore its meaning and implications from three angles – theological, philosophical, and scientific – integrating classical and modern interpretations.

Theological Interpretation

Classical Exegesis (Tafsir): Early Islamic scholars unanimously understood this verse as affirming that God cannot be physically seen by human eyes in this worldly life. For example, Tafsir al-Jalalayn explains that “the eyes cannot see Him – this is a denial [of vision] in certain circumstances” (i.e. in this life). However, based on other Quranic verses and hadith, Jalalayn notes it is accepted that believers will see Him in the Hereafter, citing “On that Day faces will be radiant, gazing upon their Lord” (Quran 75:22–23) and the Prophet’s hadith, “Verily you shall see your Lord as clearly as you see the full moon at night.” In other words, no worldly vision can grasp God, but in the hereafter God may allow the faithful to behold Him in a manner befitting His glory. Many classical scholars held this view. Ibn Kathīr (14th c.) writes unequivocally: “No vision can grasp Him in this life. The vision will be able to look at Allah in the Hereafter, as affirmed by numerous hadiths.” He even reports that the Prophet’s wife ʿĀ’ishah refuted anyone claiming the Prophet saw God in this life by quoting this verse: “Whoever claims that Muḥammad has seen his Lord [with his eyes] has uttered a lie, for Allah says, ‘No vision can grasp Him…’”

Importantly, some exegetes clarified that “grasp/perceive” (tudrik) in this verse can mean to fully encompass. They held that while God may be seen by the blessed in the hereafter, no sight can ever encompass Him completely. In this vein, it’s narrated that the early scholar Ikrima asked, “Do you see the sky?” When someone said yes, he replied, “Do you see all of it?!” – implying that even if one could see God in the next life, one could never comprehend Him fully. Another commentator, Qatāda, concluded: “Allah is greater than that anyone should ever encompass Him [in vision].” Thus, classical tafsirs offered two complementary interpretations: (1) a total negation of seeing God in this worldly life, and (2) a negation of ever fully grasping God’s essence, even if sight of Him is granted in the life to come.

Insights of Major Commentators: Prominent mufassirūn (Quran exegetes) discussed 6:103 in detail. Al-Ṭabarī (9th c.) recorded early opinions that human eyes simply do not have the capacity to perceive God in dunya (the material world). Some reports he cites suggest humans would be given a new faculty in the afterlife to behold God, since our current senses cannot bear it. Al-Qurṭubī (13th c.) in his commentary adds supporting evidence from across the Qur’an. He points to verses like “Faces, that Day, will be bright – looking at their Lord” (Quran 75:22–23) and “For those who excel is goodness and more” (Quran 10:26), where “more” was explained as the honor of seeing God. These texts, Qurṭubī notes, indicate that while no one can see God in this life, the righteous will behold Him in the Hereafter by God’s will. On the other hand, Qurṭubī mentions Quran 83:15, which says the wicked will be veiled from God, implying the righteous are not veiled.

Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (13th c.), known for his philosophical tafsīr, discusses the verse at length. He emphasizes how it underscores human limitation: our faculty of vision is bounded and cannot reach the Divine Being. Rāzī notes that two esteemed companions – ʿĀ’ishah and Ibn ʿAbbās – held differing views on whether the Prophet Muḥammad saw God during the Miʿrāj (Ascension). ʿĀ’ishah, as noted, denied it vehemently, while Ibn ʿAbbās believed the Prophet did have a vision of God (interpreted as a heart-vision or a veiled vision). Rāzī carefully reports both views and remarks that this early disagreement was handled without declaring either side heretical – illustrating an important theological principle of humility before such mysteries. He also concurs with the mainstream that any vision of God must be without encompassing Him, quoting earlier scholars: “If the eyes of the head cannot see Him, perhaps the eyes of the heart can, by God’s light” (alluding to a spiritual vision). Rāzī and others stress God’s name al-Laṭīf (“the Subtle”) here: God is so subtle and fine that He is invisible to physical eyes, yet He is al-Khabīr (“All-Aware”), fully aware of us.

Divine Transcendence in Scripture: Classical scholars link verse 6:103 with other scriptural narratives that reinforce God’s transcendence. A key example is the story of Prophet Mūsa (Moses). The Qur’an relates that Moses asked to see God, and the reply came: “You will not see Me, but look at the mountain; if it remains firm, then you will see Me.” When God manifested just a fraction of His glory to the mountain, “He made it crumble and Moses fell down unconscious” (Quran 7:143). Moses awoke and repented, realizing the magnitude of what he had requested. This dramatic incident is often quoted in tafsīrs to illustrate why no mortal vision can endure God’s unveiled presence in this life. Similarly, a famous hadith qudsī (a sacred narration) says: “His Veil is Light; if He removed it, the splendor of His Face would burn everything that His gaze reaches.” In other words, were God to fully expose Himself, creation could not survive the intensity. Such reports fortify the understanding of لَا تُدْرِكُهُ الْأَبْصَارُ – that God’s essence is far beyond the grasp of any creature’s sight, due not only to human limitation but to God’s inherent majesty.

Modern Islamic Perspectives: Contemporary scholars continue to draw spiritual lessons from this verse about God’s transcendence and human limitations. It is cited as a fundamental proof of tanzīh – the doctrine that God is utterly unlike His creation. For instance, theologians note that God is “beyond space and time,” not a material being within the universe that eyes could detect. Any physical “seeing” implies locating an object at a distance in space, but God, who created space, is not contained by it. Modern commentators often emphasize that 6:103 guides Muslims to approach God through faith, reflection, and spiritual insight rather than through empirical observation. At the same time, the verse’s second clause – “but He perceives all vision” – reassures believers that God is not distant in knowledge or awareness. He sees us even if we cannot see Him. This has practical devotional implications. The Prophet Muhammad taught the famous concept of iḥsān (spiritual excellence) in which he said: “Worship Allah as if you see Him, and even though you do not see Him, know that He sees you.”

This teaching beautifully mirrors 6:103 – we do not see God, but He sees all. Thus, Muslims are urged to remember God’s constant watchfulness (His immanence in knowledge) while affirming His inscrutable transcendence. Modern writers also use this verse to remind us that no matter how advanced science becomes, God’s essence will remain beyond human instruments – one can detect God’s signs and effects, but God Himself is not an object to be examined. In summary, the verse inculcates humility: it tells humans, “Know your limits in trying to comprehend God,” but also, “Know that God is fully aware of you.”

Sunni, Shia, and Sufi Views: All Islamic schools revere this verse, though they have nuanced theological emphases:

- Sunni Theology (Ashʿarī/Māturīdī and Salafī): Sunnis typically interpret 6:103 as denying the possibility of seeing God in this worldly life, while affirming the “beatific vision” in the afterlife. This is based on the many hadiths and verses (like 75:23) promising that the righteous will see Allah in Paradise. Sunni theologians hold that God will allow Himself to be seen in a way “without modality” (bi-lā kayf) – not like seeing a material object, but in a special manner befitting God. They argue that denial of vision in 6:103 applies to this life only. Sunni creed stresses that God has no physical form or direction, but His existence and attributes can be “seen” by the eyes in the Hereafter by His light. Importantly, Sunnis reject that God can ever be fully encompassed; even in Paradise, they will not “grasp” all of God, they will only behold what God grants of His Self. This view maintains God’s transcendence yet affirms a literal fulfillment of the believers’ longing to see their Lord.

- Shiʿa Theology (Imāmī Twelver): Shia scholars generally take an even stricter view on divine transcendence. According to Imami Shiʿi and earlier Muʿtazilite theologians, God cannot be seen with physical eyes at all – neither in this world nor the next. They argue that any vision of God would imply God is a delimited form or body, which contradicts His absolute unity and incorporeality. Shia tafsirs thus read “vision perceives Him not” as an unqualified, eternal truth: no eye will ever literally see God, because God is not a visible object. When Sunnis cite reports of seeing God in the Hereafter, Shia scholars often reinterpret those narrations as seeing God with the inner eye or seeing His light or glory, not a direct sight of God’s essence. They also point to how Moses was told “you will not see Me” (Quran 7:143) as evidence. In Shia thought, the greatest reward in Paradise is knowledge of God and closeness to Him, rather than any kind of visual encounter. The line “He is the Subtle, the All-Aware” reinforces for them that God’s presence is felt in subtle, inward ways, not in anthropomorphic terms. In sum, Shia theology heavily emphasizes God’s transcendence and incomparability, aligning with the literal sense that no vision can ever capture Him.

- Sufi Mystical Perspective: Sufi teachers deeply reflect on this verse, often in an experiential context. They concur that God cannot be seen with the physical eyes, yet they speak of a kind of spiritual “seeing” (mushāhada) of God achieved by the heart. For Sufis, “the eye of the heart” (basīrat al-qalb) can perceive divine realities that the fleshly eyes cannot. They highlight God’s name al-Laṭīf (the Subtle) in this verse – indicating that God pervades the world in an unseen, delicate manner, “penetrating everything no matter how small.” Sufi commentators often cite the hadith of iḥsān (mentioned above) as an invitation to “see” God with one’s inner awareness even if one’s eyes do not see Him. In practice, this means cultivating a constant consciousness of God’s presence. Some Sufi poetry goes so far as to say “Wherever I look, I see God’s Face”, meaning the realized mystic perceives God’s signs in all things (echoing Quran 2:115). However, this is understood not as seeing God’s essence, but seeing God through the veil of creation. Notably, most Sufis still adhere to mainstream Sunni creed regarding the afterlife – i.e. that the ultimate vision of God is a grace granted in Paradise. Yet, they place less emphasis on the physicality of that event and more on the ecstasy and love of encountering the Divine. Sufi metaphysics also adds an interesting nuance to immanence: many Sufis teach that God is “the Only Reality” and creation is like a shadow. So, God is utterly transcendent (beyond form), and yet immanent as the very ground of being. In the words of one Sufi, “He is with you by His Essence everywhere” – a statement not meant physically, but metaphysically (i.e. God’s existence is sustaining everything at every moment). In summary, Sufis take 6:103 as a call to seek God beyond the sensory realm, through purification of the heart, until one “sees” by the light of faith what the eyes alone cannot see.

Philosophical Analysis

Metaphysical Implications: Philosophically, “Vision perceives Him not” raises the issue of the limits of human knowledge in encountering the Absolute. It asserts that God, as the ultimate reality, is transcendent – beyond the empirical and sensory realm. This aligns with the idea that a finite mind cannot fully comprehend an infinite being. Islamic theologians often quote, “Whatever concept of God you form in your mind, know that God is different from that”, underscoring that the divine essence exceeds human ideas. The verse draws a contrast between the seer and the Seen: human vision is narrow and contingent, whereas God’s being is limitless. Simultaneously, “but He perceives all vision” establishes God as omniscient – metaphysically, God is the subject who is never an object, the Knower who is never known against His will. This dichotomy has led Muslim philosophers to discuss God as the Noumenon (in a sense): the reality behind all phenomena that cannot itself be observed directly.

Parallels in Western Epistemology: The Quranic teaching here finds resonances in Western philosophical thought about the limits of perception. Two famous examples:

- Kant’s Noumenon: Immanuel Kant distinguished between phenomena (the world as we experience it through our senses and mind) and the noumenon or “thing-in-itself” (the reality that exists independently of our perception). Kant argued that our speculative reason can know phenomena but can never penetrate to the noumenal realm. The noumenon is inherently beyond our sensory experience. Many philosophers have identified God with the idea of a noumenal reality – essentially what Kant called a “boundary concept” for human knowledge. We can infer that God exists (through reason or moral intuition, in Kant’s view), but we cannot perceive God through empirical means. This is strikingly similar to the message of 6:103: that God (the ultimate “thing-in-itself”) cannot be grasped by our eyes. Our knowledge of Him is therefore either indirect or of a different kind (spiritual, moral, etc.). Kant’s framework thus philosophically mirrors the Quranic stance that there is an insurmountable gap between the Ultimate Reality and our sensory cognition. Yet, Kant also held that practical reason (moral awareness) necessitates belief in God’s existence – one might say Kant allowed that while we cannot see God, we must postulate Him to make sense of our innate moral striving. Likewise, the Quran invites us to know God through signs and moral/spiritual insight, even though we cannot literally see Him.

- Plato’s Theory of Forms: Centuries earlier, Plato had illustrated the difference between appearance and reality in his famous Allegory of the Cave. In the allegory, prisoners see only shadows on a wall, taking those shadows for reality, while the true objects and the light of the sun remain unseen to them. Plato describes how the philosopher, like a prisoner freed from the cave, comes to realize that the sensory world is only a shadow of a higher reality. He introduced the concept of Forms – ideal realities such as Justice, Beauty, the Good – which are not accessible to the senses, only to the intellect. The highest of these is the Form of the Good, often compared to the divine. The cave analogy explicitly states: “The shadows represent distorted copies of reality we perceive through our senses, while the objects under the sun represent the true forms that we can only perceive through reason.” We can draw a parallel: our eyes see the “shadows” (the material world), but the ultimate truth (God) is like the sun – too bright to look at directly from within the cave of material existence. Just as the cave’s prisoners needed to turn away from the shadows to behold the sun, humans need to go beyond sensory appearances to perceive the Divine truth. In Islamic philosophy, some thinkers equated Plato’s Form of the Good with God, arguing that God is known not by vision but by intellectual and spiritual illumination. The notion that true knowledge requires looking beyond what the eyes can see is common to Plato and the Qur’an. In fact, Quran 6:103 could be seen as a concise, revealed assertion of what Plato illustrated allegorically: the Absolute Good (God) is not directly seen by human eyes, though its light makes all things known (in the verse, God “perceives all vision” – He is like the light that sees us and makes sight possible).

Islamic Philosophical Theology: Within the Islamic tradition, philosophers and theologians also grappled with the divide between God’s knowledge and human knowledge. The Aristotelian-influenced philosopher Al-Fārābī and the great Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā) described God as the Necessary Existent whose essence is identical to His existence – a reality so absolute that human minds can only approach it through abstraction and metaphysics, not through imagination or sensory image. Ibn Sīnā argued that God knows all things in a single unified act of intellection, whereas humans know things sequentially and partially; this again highlights that God’s mode of perceiving is fundamentally different from ours. Later, theologian-mystics like Al-Ghazālī and Ibn ʿArabī spoke of “knowledge of God” in terms of experience (dhawq) and unveiling (kashf). They taught that while God cannot be seen by the eye, He can be known by the purified heart – a concept akin to what we discussed in Sufi perspectives. All of these discourses rest on the acceptance that there is a metaphysical horizon that normal human cognition cannot cross. As Ghazālī put it, one must “polish the heart to mirror the Unseen” – implying the truth of 6:103 that one’s inner faculty must be used since the outer eye will fail.

Divine Immanence vs. Transcendence: Verse 6:103 also touches on the classic theological balance between God’s transcendence and immanence. “Vision perceives Him not” is a clear statement of transcendence: God is above and beyond being an object in the world. Yet the verse immediately adds, “but He perceives [all] vision”, which implies a kind of immanence: God is closely involved in the world, seeing and knowing every detail. Moreover, God is called *“Al-Laṭīf” (the Subtle) in this verse – a name which can imply being beyond perception, but also means being intimately gentle and present in fine details – and *“Al-Khabīr” (the All-Aware) – fully aware of even the hidden aspects of creation. Philosophically, this presents God as radically transcendent (utterly unlike the world, not accessible to the senses) and radically immanent in terms of knowledge and power (nothing escapes His perception). Islamic thought, especially in the Sunni tradition, holds that God is “above the Throne” (symbolic of transcendence), yet “with you wherever you are” in His knowledge and support (Quran 57:4).

Balancing these attributes has been a rich discussion. Some theologians leaned more toward transcendence – for example, insisting God has no literal “place” or material presence, only actions and knowledge in the world. Others (like certain Sufis) spoke in more immanent terms – describing God as present “by His essence” everywhere (though they clarified this does not mean God is a physical part of the universe, but rather existence itself is entirely dependent on God’s Being at every moment). In Christian philosophical theology, one finds a similar discussion: e.g. how an infinite God is both beyond and within creation, and thinkers like Thomas Aquinas concluded that we can know that God is (that He exists), but not what He is – paralleling “vision perceives Him not”. Aquinas also held that Beatific Vision (seeing God in the hereafter) is possible only by a special light of God given to the soul, since the human intellect by itself cannot see the divine essence. This resonates with Islamic views (Sunni and Shia) that only by God’s light and power can the barrier of un-seeability be overcome, and only in the next life. In modern philosophy of religion, 6:103 might be cited in discussions of negative theology – the idea that we best approach God by saying what He is not (in this case, not visible, not fully knowable) rather than what He is. It is also relevant to debates about empiricism vs. rationalism in knowing God: empiricists might say “I cannot believe in what I can’t see,” whereas the Quran here responds, “God by nature can’t be seen, but you can know Him in other ways.”

In summary, the verse underlines a core epistemological principle: the Ultimate Reality is not directly accessible to human senses or total comprehension. Both Islamic and Western philosophers have affirmed this in their own terms – whether speaking of noumenon vs. phenomenon, Forms vs. shadows, or Creator vs. creation. Yet, this does not lead to despair of knowing, because knowledge can be obtained through indirect means (reason, signs, spiritual insight) and because that Ultimate Reality is, reciprocally, knowing us. Indeed, human knowledge of God will always be partial, but God’s knowledge of us is total. The transcendence keeps us intellectually humble, while the immanence (His all-seeing awareness) keeps us spiritually accountable and comforted.

Scientific Perspective

At first glance, one might think a 7th-century scripture about God has little to do with modern science. Yet Quran 6:103 carries a message about human perceptual limits that is remarkably consonant with contemporary scientific understanding. It essentially says: there are realities that human vision cannot reach. Science has discovered this truth in multiple ways:

Limits of Human Senses: Our biological senses are extremely limited instruments. Modern physics shows that humans perceive only a narrow band of reality. For example, the human eye is sensitive only to the visible light portion of the electromagnetic spectrum – roughly wavelengths from 380 to 700 nanometers. This is actually a tiny slice of the full spectrum of light. It’s often noted that the human eye can detect only about 0.0035% of the entire electromagnetic spectrum. All the colors and daylight we see make up less than a ten-thousandth of the spectrum’s range (which extends from radio waves miles long to gamma rays smaller than atoms). In essence, 99.9965% of all light waves are invisible to us! Similarly, our hearing covers only a limited frequency range (about 20 Hz to 20 kHz), we cannot smell as well as many animals, and we have no direct senses for things like electrical or magnetic fields. This scientific fact – that our unaided vision (and other senses) miss most of reality – echoes the verse’s implication that there is far more to reality than humans can directly perceive. If we cannot even see ultraviolet or infrared light, how could we expect to see the Creator of light Himself? The “vision” of our eyes is simply not designed to take in all that exists.

Neuroscience of Perception: Interestingly, neuroscience reveals that even the limited data our eyes do gather is heavily processed and filtered by the brain. There is a literal blind spot in each of our eyes (where the optic nerve connects to the retina) where we are effectively blind, but we never notice it – the brain fills in the gap seamlessly based on surrounding patterns. What we “see” is partly constructed by our mind. We don’t passively receive reality; our brains actively interpret signals, sometimes guessing or simplifying. Optical illusions dramatically demonstrate how our visual perception can be fooled – we might be looking at something but perceive it incorrectly because the brain misinterprets the input. In short, seeing is not equivalent to understanding reality as it is. Our vision is a useful tool, but it has a narrow focus and can easily mislead or be limited. This resonates with the verse’s deeper message: no human mode of seeing can grasp the fullness of truth. Just as our eyes can fail us with a simple magic trick or hallucination, certainly they cannot be the tool to fathom an infinite divine being. The Quran’s phrasing “lā tudrikuhu al-abṣār” can be understood as “vision does not comprehend Him” – which aligns with the idea that even if we gather visual data, comprehension is a further leap. Neurologically, our brains would have no framework to even process a “sight of God,” since all our perception is based on finite created things.

Unseen Realities in Physics: Modern physics has uncovered layers of reality that are invisible to the eye – and sometimes even conceptually mind-bending. A good example is quantum mechanics. Subatomic particles like electrons and photons cannot be seen with the naked eye, of course; we observe them indirectly via instruments. But more profoundly, these entities often behave in ways that defy visualization. An electron in an atom does not orbit like a planet that we could theoretically watch; instead, it exists as a smeared-out wavefunction – a cloud of probability. When we attempt to observe it, it “collapses” to a definite state. This famous observer effect in quantum physics means that the act of observing something at the quantum level inevitably disturbs it. We cannot simultaneously know a particle’s exact position and momentum (Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle); the very notion of a deterministic “trajectory” that one could watch doesn’t apply at that scale. In essence, the fundamental fabric of reality is not fully observable – it’s partly hidden in a realm of potentiality that we can only probe indirectly. The more scientists have peeled back nature’s layers, the more we find that invisibility and unobservability are built into the universe. Fields, forces, virtual particles – much of what physics deals with is known by its effects, not by direct sight.

Cosmology and the Unobservable: On the cosmic scale, we also encounter the unseen. Astrophysicists talk about dark matter and dark energy – which together comprise about 95% of the known universe’s content – that are, by definition, invisible and undetectable by direct electromagnetic observation. Dark matter is a form of matter that does not interact with light, so we cannot see it with telescopes; yet we know it exists because we can observe its gravitational effects on stars and galaxies. It literally “perceives us not” (from our perspective), but it’s out there shaping the cosmos. Dark energy, even more mysterious, is an unseen force causing the accelerated expansion of the universe. In addition, the universe has an observable horizon. There is a limit to how far we can see – about 46 billion light years – beyond which light has not had time to reach us. “There is a point in the cosmos beyond which, even with our most powerful telescopes, we cannot see.” What lies beyond that cosmic horizon is inherently unobservable to us, at least by any direct means. Thus, even in principle, science acknowledges there are portions of reality (in space and time) that human observation will never access.

Bringing these examples together: physics and cosmology affirm that “not seeing something” is not a proof of its non-existence. We don’t see ultraviolet light without instruments – but it exists. We don’t see the quantum wavefunction – but it’s real and manifests in experiments. We don’t see dark matter – but it’s there, holding galaxies together. In the same way, the fact that no vision can catch God does not mean God is not there; rather, God — like many fundamentals of reality — is known by His effects and signs. The Quran often points to natural phenomena as āyāt (signs) of God, inviting us to infer the Artist from the art. In scientific terms, we might say we observe the footprints of God, but not God Himself. A 20th-century astrophysicist, for instance, might marvel at the fine-tuned laws of nature and see in them an indirect vision of the Creator’s wisdom.

Science and Theology – Converging Insight: There is a profound intersection where science and the message of 6:103 meet: in humility about human knowledge. As science advances, rather than eliminating mystery, it often uncovers deeper mysteries – realms our senses can’t probe and our theories struggle to describe. Likewise, theology begins with the premise that the Divine is beyond our grasp, yet invites us to seek understanding through other avenues (like scripture, rational reflection, mystical experience). Both disciplines, at their best, encourage a sense of wonder. A scientist gazing into the vastness of space or the subatomic depths realizes how much is unseen and unknown. A believer contemplating God reflects on how all-encompassing and unobservable His essence is. In fact, this Qur’anic verse can harmonize with a scientific mindset: it encourages us to acknowledge a reality larger than what our eyes can take in.

Some scientists have even commented in quasi-theological terms about the limits of observation. Renowned physicist Werner Heisenberg noted that our scientific observations are limited by our modes of inquiry – “What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning,” highlighting that we never grasp reality in its pure form. Such insights echo the idea that only God “perceives all vision” – only the ultimate Knower sees reality fully. Human knowledge, though powerful, always has edges beyond which lies the unknown. The Qur’an taught this principle in spiritual terms, and science reinforces it in empirical terms.

Ultimate Reality Beyond Observation: In cosmology, thinkers sometimes discuss the concept of a “Theory of Everything” or the ultimate laws of nature. Yet even if such a theory is found, scientists admit, there may always remain the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” or “What breathes fire into the equations?”. Such questions point to an reality that science alone may not illuminate. Here, theology comfortably steps in with the concept of God – the unobservable source of all that exists. Notably, even if one doesn’t accept theological answers, science still requires a kind of faith in unobservables (like believing in electrons or multiverses based on indirect evidence). The verse “He is the Subtle, the All-Acquainted” beautifully captures the idea of an unseen foundation of reality that is nonetheless aware of us. One might compare this to how science speaks of invisible fields permeating the universe. For believers, of course, God is not an impersonal field but an all-knowing Creator with will and intent.

In conclusion, Qur’an 6:103 offers a timeless reminder of human limitations that resonates across theological, philosophical, and scientific thought. The theologian sees in it a call to humility before God’s transcendence and a comfort in His omniscience. The philosopher sees an affirmation that the highest truth – the Absolute, the Real – surpasses sensory and even intellectual total grasp, much as thinkers from Plato to Kant surmised. The scientist can see in it a poetic foreshadowing of our modern understanding that much of the universe is hidden from our eyes and instruments, yet we discern truths by observing their effects. Despite approaching from different angles, all three perspectives converge on a common theme: ultimate reality is only partly within our reach, and a great deal lies beyond the horizon of human perception. As the verse itself concludes, while we cannot encompass the Divine with our sight, God in His subtlety encompasses us – a profound point to ponder whether one is studying scripture, philosophy, or the starry heavens.

Sources:

- Quran 6:103 and classical Tafsīr (exegesis) by al-Jalalayn, Ibn Kathīr, al-Ṭabarī, al-Qurṭubī, and Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī surahquran.comsurahquran.com islamicstudies.infoislamicstudies.info.

- Hadith of the Prophet on the Beatific Vision (Bukhārī, Muslim) and ḥadīth of ʿĀ’ishah denying any worldly vision of God surahquran.com.

- Shiʿi and Muʿtazilite perspective denying physical vision of God en.wikishia.neten.wikipedia.org.

- Philosophical parallels: Kant’s critique of pure reason (noumenon vs phenomenon) britannica.com; Plato’s Republic (Allegory of the Cave) en.wikipedia.org.

- Scientific facts on human perception limits: visible spectrum ~0.0035% of EM spectrum youmeandspirit.com; brain filling in blind spot en.wikipedia.org; dark matter unseen by telescopes en.wikipedia.org; cosmic observation horizon psu.edu.

- Heisenberg’s observer effect in quantum physics en.wikipedia.org. (All links accessed and verified.)

Leave a comment