Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

1. Quranic Verses on Astronomy and Mathematics

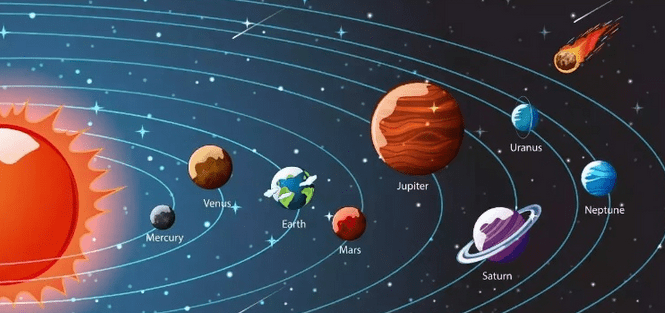

The Quran contains numerous verses that reference celestial bodies and emphasize order and calculation in nature. For example, “The sun and the moon [move] by precise calculation” (Quran 55:5) and “He made the sun a radiant light and the moon a light, and determined for it phases – that you may know the number of years and the reckoning (hisāb)” (Quran 10:5) explicitly link the motions of the Sun and Moon to the concept of hisāb, meaning calculation or mathematics. Another verse states, “We have made the night and the day as two signs… that you may seek bounty from your Lord and know the number of years and the account (hisāb)” (Quran 17:12), again tying the regular alternation of day and night to the idea of counting and calculation. The Quran also describes the orderly orbits of the heavens: “It is He who created night and day, the sun and the moon; each floating in its orbit” (Quran 21:33) and “The sun cannot overtake the moon, nor can the night outpace the day; each floats in an orbit” (Quran 36:40) – verses that portray a cosmos governed by precise laws. Such passages convinced early Muslims that the universe operated on knowable principles and inspired them to investigate celestial phenomena with mathematical rigor.

The Arabic term hisāb (calculation) in these verses was understood as a divine encouragement to quantify and measure, laying a religious impetus for developing astronomy and mathematics. Muslim scholars viewed the study of the stars and planets as deciphering the “Signs” of God in nature, an exercise of faith as well as intellect.

This Quranic worldview helped spark a spirit of scientific inquiry. In the words of one historian, “Muslims understand everything in the universe as a letter from God Almighty inviting us to study it.”

The emphasis on knowledge in Islam – with verses commanding “Read!” and others asking believers to observe and reason – created a culture where exploring astronomy and mathematics was seen as pursuing religiously inspired knowledge. Prophetic traditions reinforced this ethos (“Seek knowledge from cradle to grave,” taught the Prophet Muhammad), so it is no surprise that the earliest Muslim scholars were motivated to master the sciences. The Quran’s specific references to the sun, moon, stars, and orbits as operating with measure and accuracy gave Muslim scientists confidence that the heavens followed a logical order that could be expressed in mathematical terms. In short, the Quran served as an intellectual catalyst, encouraging believers to study the cosmos and its mathematical laws as a way to appreciate the wisdom of the Creator.

2. Development of Astronomy in the Islamic Golden Age

Astronomy flourished during the Islamic Golden Age (8th–14th centuries) as scholars refined celestial models, improved timekeeping methods, and pioneered observational techniques – often guided by Quranic principles of order. In the 9th century, the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma’mun established the renowned House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where astronomers were supported in translating Greek and Indian works and then going beyond them. The first major original Islamic astronomical text, Zīj al-Sindhind by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 830 CE), compiled tables for the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets and introduced new calculations derived from Indian astronomy. This work marked a turning point – moving from mere translation to active development of new astronomical ideas. It was no coincidence that Al-Khwārizmī was also a Quranic scholar; he and his contemporaries saw investigating planetary motions as part of understanding the divinely ordained order of time (for example, to create accurate lunar calendars for Islamic rituals).

Observational astronomy became increasingly sophisticated. The first systematic astronomical observations in Islam were conducted under Caliph Al-Ma’mun’s patronage. He sponsored measurements of a degree of latitude on Earth’s surface (to calculate Earth’s circumference) and organized observations of the Sun, Moon, and planets from observatories in cities like Damascus and Baghdad. These teams established solar parameters, refined the length of the solar year, and produced star catalogs. By the 10th century, observatories and research centers had spread across the Islamic realm. For instance, the Buyid rulers built large instruments around 950 CE for precise observations, and astronomers like Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (Azophi) revised Ptolemy’s star catalog, discovering new stars and constellations. Crucially, Islamic astronomers improved upon the Ptolemaic model of the heavens: they identified weaknesses in Ptolemy’s geocentric system and began eliminating quirks like the equant (an off-center point in planetary orbits) to make models more consistent with uniform circular motion – a move driven by the idea that nature’s design should be elegant and exact.

One of the great early astronomers, Al-Battānī (Albategnius, d. 929), compiled a landmark set of astronomical tables (Kitāb az-Zīj) based on decades of observations. He refined the values for the length of the year and the orbits of the Sun and Moon with unprecedented accuracy. Al-Battānī’s work in determining solar apogee and orbital eccentricity exemplified the precision that Quranic verses like “the sun and the moon follow courses exactly computed” inspired. His tables were so reliable they remained in use for centuries; in fact, Nicolaus Copernicus cited Al-Battānī at least 23 times in De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and praised his observations. Likewise, Al-Farghānī (Alfraganus, 9th century) wrote Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions around 833 CE, which provided a clear, updated summary of Ptolemaic astronomy with improved measurements. Al-Farghānī’s textbook gave more accurate figures for astronomical constants (such as the Earth’s diameter and the distances of planets) and was widely circulated; it was later translated into Latin in the 12th century, becoming a standard astronomy text in Europe. Through such works, Muslim astronomers brought the abstract models of antiquity into closer alignment with observational reality, driven by their conviction that “Allah has not created this but in truth” (Quran 10:5) – meaning the cosmos truly follows the orderly principles one observes.

Another major development was in astronomical instruments and timekeeping. Muslim scientists perfected the astrolabe, a Greek invention that Muslim engineers enhanced with angular scales and star charts to solve practical problems. By the Golden Age, astrolabes could determine local time, latitude, the times of sunrise and sunset, and the direction of Mecca (qibla) – all vital for Islamic prayer schedules and calendar dates. Many Islamic astrolabes were also beautifully decorated with calligraphy and Quranic verses. For example, some astrolabes feature the Bismillah (“In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate”) or the Throne Verse (Ayat al-Kursī, Quran 2:255) engraved on them, reflecting how faith and science were intertwined. The intricate Safavid-era astrolabe shown above is inscribed with the Bismillah and was used for both astronomy and astrology in 17th-century Persia. Such instruments allowed scholars to apply mathematical calculations (hisāb) directly to observing the heavens, embodying the Quranic ideal of an ordered universe. Islamic astronomers also innovated with observatories on an unprecedented scale. In the 13th century, the Mongol ruler Hülegü Khan invited Nasir al-Din al-Tusi – one of the era’s leading astronomers – to build a major observatory at Maragha (in present-day Iran). Al-Tusi’s Maragha observatory (established 1259 CE) assembled the best astronomers of the day and housed large custom-built instruments (e.g. mural quadrants and armillary spheres). Over 50 years, this team produced improved planetary models and star catalogs, making “important modifications to the Ptolemaic system.” Al-Tusi himself introduced the famous “Tusi couple,” a mathematical device that generates linear oscillation from the sum of two circular motions – this clever geometric model allowed him to eliminate Ptolemy’s problematic equant and model planetary motions with uniform circular orbits. His work Tadhkira fi ‘ilm al-hay’a and the new star tables (Zīj-i Ilkhānī) compiled at Maragha became reference works for later astronomers. The Maragha school’s influence was profound: historians note that Copernicus later employed an identical geometric arrangement to the Tusi couple in his heliocentric system, suggesting a possible transmission of ideas from Maragha to Renaissance Europe. Similarly, in Damascus, the astronomer Ibn al-Shātir (14th century) improved lunar and planetary models; his lunar model (eliminating the eccentric deferent) matches Copernicus’s model point for point. These advances all trace back to the Islamic commitment to refine celestial models to better fit observation and “mathematical design,” an approach rooted in the conviction that the Creator “has subjected the sun and moon, each running for an appointed term. He regulates it all…” (Quran 13:2).

Islamic astronomy also revolutionized timekeeping and calendar-making. Muslim astronomers developed tables (zijes) for timekeeping that were used to regulate the five daily prayers and the months of the lunar Hijri calendar. The need to determine prayer times at various latitudes spurred the development of precise sundials and trigonometrical calculations. Most medieval Islamic astronomy textbooks included a chapter on finding the qibla (direction of Mecca) and prayer times, underscoring how astronomy was directly applied to Islamic religious needs. By the ninth and tenth centuries, they had devised mathematical methods (including spherical trigonometry) to compute the qibla from any location on Earth. This was a complex geographic problem – essentially finding the great-circle direction – and its solution by scholars like Al-Battani, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Yunus represents an early triumph of mathematical astronomy in service of faith. In the 11th century, astronomer-poet Omar Khayyám led a team to reform the calendar under Sultan Malik Shah. They designed the Jalālī calendar (1079 CE), a solar calendar with extremely accurate intercalation – it had an error of only one day in about 5,000 years, more exact than the later Gregorian calendar. This calendar reform again reflected the fusion of observational precision and mathematical calculation (hisāb) that Islamic science achieved, driven by the quest to align human time-reckoning with the celestial order described in the Quran.

Prominent figures like Al-Battānī, Al-Farghānī, and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi thus advanced astronomy on multiple fronts. Al-Battānī’s legacy includes refining planetary orbits and producing tables of sines and tangents that aided astronomical calculations; Al-Farghānī improved understanding of planetary distances and wrote an accessible astronomy primer that educated generations; Al-Tusi created the most accurate planetary models of his time and is even credited as a pioneer of trigonometry as a separate field (which he needed for precise astronomical modeling). Through their work, the geometric models of the heavens were honed to new precision and the ability to predict celestial events (e.g. eclipses, conjunctions) greatly enhanced. By the end of the Golden Age, Islamic astronomers had compiled extensive star catalogs, improved the accuracy of the measured axial tilt of the Earth and the precession of the equinoxes, and even debated ideas like the possible rotation of the Earth (centuries before Galileo). In sum, the Quranic vision of a universe of balance (mīzān) and calculation (hisāb) propelled Muslim scholars to transform astronomy from its ancient roots into a precise science.

3. Mathematical Advancements Influenced by the Quran

Hand in hand with astronomy, mathematics flourished in the Islamic Golden Age, powerfully influenced by Quranic concepts of enumeration, calculation, and order. The Quran’s references to “reckoning” and “accounting” (hisāb) encouraged Muslims to develop sophisticated math for practical and intellectual purposes. One direct impact was on the birth of algebra. Islamic inheritance laws, which are detailed in the Quran, allocate fixed fractional shares to family members. Solving inheritance distribution problems often requires solving linear equations – a challenge that spurred early mathematicians to formalize algebraic methods. In fact, “mathematics was introduced into Muslim culture through the Holy Qur’an where complex rules of inheritance are outlined.”

The scholar Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780–850) is known as the “Father of Algebra” for his groundbreaking book Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa’l-muqābala (“The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing”), from which the word al-jabr (algebra) comes. Al-Khwārizmī explicitly states in his introduction that he wrote this treatise to solve practical problems of society – “to serve the people’s practical needs concerning inheritance, legacies, partition, lawsuits, and commerce.”

His choice of title notably uses the word ḥisāb (calculation), echoing the Quranic emphasis on reckoning. In this work, he systematized how to solve linear and quadratic equations, providing algorithms that allowed these calculations to be done routinely. By abstracting problems into equations, Al-Khwārizmī’s algebra was a direct fulfillment of the Quranic invitation to “know by number and calculation.” It was a revolutionary shift away from the purely geometric mathematics of the Greeks, creating a new symbolic language that could handle any quantities – rational, irrational, geometric magnitudes – as algebraic objects. This broad algebraic approach opened an entirely new path for mathematics, one that made later advances (from polynomial algebra to calculus) possible.

Beyond algebra, Quranic influence is seen in Muslim contributions to trigonometry and geometry. The Quran repeatedly alludes to the importance of measuring angles and direction – for instance, determining the qibla or the phases of the moon. Such needs drove mathematicians to develop trigonometric methods. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a standalone discipline. In the 13th century he wrote “Treatise on the Quadrilateral” which laid out the laws of sines and cosines for plane and spherical triangles. He and earlier scholars like Abu’l-Wafā’ and Al-Bīrūnī established all six trigonometric functions and compiled tables of their values to high precision. Al-Tusi’s trigonometry was indispensable for accurate astronomy, but it also became a foundation for surveying and architecture – areas valued in Islamic societies (for example, to calculate the exact orientation of mosque foundations toward Mecca). “Some of the greatest astronomers, including Johannes Kepler, were also astrologers… important advances in mathematics came directly out of astronomy. By looking at the heavens, mathematicians were able to pick out patterns in much purer form,” notes science historian David Bressoud. Indeed, Al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) demonstrates this interplay: he used trigonometry extensively to map the globe and even measured the Earth’s radius by observing mountain heights and applying geometric formulas. His works discuss “the sine theorem in the plane, and solving spherical triangles,” topics at the heart of advanced trigonometry. Al-Bīrūnī’s calculations enabled him to determine geographic coordinates of many cities and the direction and distance to Mecca from each – a clear example of religious inspiration (accurate qibla determination) driving mathematical innovation. By the 10th century, Muslim mathematicians had also adopted the Hindu concept of the sine (jiba) in place of the Greek chord, making trigonometric computation far more efficient and setting the stage for later use of trigonometry in physics and engineering.

Islamic advances in optics and geometry were likewise stimulated by a desire to understand the natural signs described in the Quran – particularly the phenomena of light and vision. The Quran uses light as a symbol of divine knowledge (“Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth…” Quran 24:35) and discusses eyes and sight, prompting curiosity about how vision works. The 11th-century scholar Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) took up this challenge and founded the science of optical physics. In his monumental Kitāb al-Manāẓir (Book of Optics), Ibn al-Haytham combined empirical experimentation with geometric analysis to explain light rays, reflection, refraction, and the anatomy of the eye. He was deeply motivated by a rationalist outlook that harmonized with Quranic thought – that truth in nature is best discovered through observation and reason. He famously corrected the Greek idea that “we see by rays from the eyes” and proved instead that vision occurs when light rays enter the eye from external sources, using geometric optics to demonstrate how images form on the retina.

This breakthrough laid the groundwork for the later development of lenses and cameras. While Ibn al-Haytham’s work was not overtly a Quranic exegesis, it flourished in a culture where the study of light was seen as almost a spiritual pursuit (given the Quran’s reverence of light). His precise use of geometry to analyze natural phenomena epitomizes the Quranic insistence on burhān (clear proof) in understanding God’s creation. Importantly, Ibn al-Haytham’s method – combining mathematical modeling with experiments – influenced scientific methodology in general. European scientists like Kepler, who expanded on optical theory, and later Newton, who studied light’s spectrum, were directly inspired by Alhazen’s work. Thus, the mathematical approach to optics initiated by a Muslim scholar became a stepping stone to modern physics.

Moreover, the Quran’s numerical content and structure intrigued Muslim intellectuals and inspired a philosophy of numbers and harmony in nature. Scholars noted, for instance, that the Quran uses certain numbers symbolically (seven heavens, twelve months, etc.) and even observed subtle numeric patterns: the word for “day” in Arabic (yawm) appears 365 times in the Quran, and “month” (shahr) 12 times, paralleling the length of a solar year and number of months. Whether coincidental or not, such patterns reinforced the idea that numbers underlie the cosmos. Islamic civilization developed a fascination with numeric symmetry and proportions – visible in its art and architecture (geometric patterns, arabesques, the use of the golden ratio in design) and in mystical studies like Ilm-al-Jafr (numerology). Mathematicians like Thābit ibn Qurra not only translated and expanded Greek number theory but also delved into numeric puzzles and harmonic ratios, seeing mathematics as the language of creation. The Quran’s mention of precise measures – e.g. “Everything We have created is by measure” (Quran 54:49) – gave philosophical backing to the idea that natural phenomena have mathematical relationships. This inspired Muslim thinkers to search for mathematical harmonies in music (Al-Kindī explored the connection of music intervals to cosmic order) and in astronomy (the idea of an elegant geometric model for planetary motions was as much an aesthetic goal as a scientific one). Even al-Khwarizmi’s work on arithmetic (he popularized the Hindu-Arabic numerals and decimal system in the Muslim world) was called Kitāb al-ḥisāb (Book of Calculation), reflecting a culture that celebrated calculation. By introducing the zero and place-value system to the West, Muslim mathematicians enabled more complex calculations and the concept of algorithmic repetition – the very word “algorithm” is derived from al-Khwarizmi’s name. This facilitated everything from bookkeeping to astronomical computation and is a cornerstone of modern computing as well.

In summary, the Quran’s influence on Islamic mathematics was multifaceted: it directly motivated the formulation of algebra to solve Quranic legal requirements; it fostered the development of trigonometry to fulfill religious duties like determining prayer times and qibla; it nourished a mindset that sought logical and geometric explanations for natural phenomena, leading to advances in optics and mechanics; and it imbued scholars with a reverence for number and order that made mathematics “the metaphor against which all other sciences are checked.”

By treating the natural world as an interconnected system subject to calculation, Islamic mathematicians laid critical groundwork for later scientific revolutions.

4. How Islamic Astronomy and Mathematics Advanced Civilization

The achievements in astronomy and mathematics during the Islamic Golden Age had lasting impacts on civilization, both within the Muslim world and beyond. Practically, they revolutionized navigation, timekeeping, and calendar systems, and intellectually, they seeded developments that the European Renaissance and Scientific Revolution would later harvest.

One of the most immediate applications was in navigation and geography. Muslim explorers and traders, sailing vast distances from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean, relied on the stars for navigation. The refinement of astronomical tables and instruments underpinned this seafaring expertise. Islamic astronomers produced detailed star catalogs, many of which were translated or adopted by Europeans – it is telling that a significant number of stars in the night sky still bear Arabic names (e.g. Aldebaran, Altair, Deneb) and astronomical terms like zenith, azimuth, and nadir are of Arabic origin. These names entered European vocabularies through Latin translations of works like Al-Sufi’s Book of Fixed Stars and other zijes. With tools like the astrolabe and later the Mariner’s astrolabe (a navigational adaptation pioneered by Portuguese mariners but based on Islamic designs), navigators could determine latitude by the height of the Pole Star or Sun. The improved knowledge of the Earth’s circumference (thanks to measurements by Al-Ma’mun’s astronomers and later Al-Biruni) and the use of gridded coordinates in maps (Al-Khwārizmī’s geographic tables gave latitude/longitude of hundreds of places) enabled more accurate cartography. This geodesic foundation was crucial for the age of exploration; for instance, Christopher Columbus and other European explorers used maps and data partly derived from earlier Muslim geographers. In a very real sense, the Islamic preservation and enhancement of Ptolemaic geography and spherical astronomy set the stage for global navigation.

Advances in timekeeping were another civilizational contribution. The daily rhythm of Islamic life – the five prayers – and the lunar Hijri calendar (for rituals like Ramadan and Hajj) required precise determination of time. Muslim astronomers devised astrolabes with engraved prayer lines and sine quadrants to quickly find the times of the five prayers from the sun’s altitude. They also built elaborate water clocks and sundials; for example, the giant sundial of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and the timekeeping devices described by Al-Jazarī (13th century) were marvels of engineering. The role of astronomy in determining the prayer schedule and the religious calendar meant astronomers held important positions (Ibn al-Shātir was the timekeeper of the Damascus mosque). The need to calculate the lunar months (which begin with the sighting of the new crescent) led to accurate models of lunar motion and conjoined lunar-solar calendars. In the Ninth century, Muslim scholars developed algorithms to predict the visibility of the new moon – a challenging problem involving both astronomy and local atmospheric conditions. Over time, Muslim cities could rely on calculated calendars that were then confirmed by observation, increasing the efficiency of calendar administration.

Crucially, Islamic astronomers’ work on calendar and time finding directly informed calendar reforms in other cultures. The Jalali calendar reformed by Omar Khayyam was noted by later scholars for its accuracy, and it influenced the development of the Persian Solar Hijri calendar still used in Iran and Afghanistan today. When Europe faced the inaccuracies of the Julian calendar, the extensive astronomical knowledge preserved in Arabic (such as more precise tropical year lengths) was part of the discourse that led to the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582. Meanwhile, in East Asia, Islamic astronomy also made inroads: Muslim astronomers in China (e.g. at the Yuan Dynasty’s Islamic Astronomical Bureau in Beijing) introduced methods for calendar computation and planetary tracking that improved Chinese calendars.

The influence of Islamic astronomy and mathematics on Renaissance Europe was profound. By the 12th century, a massive translation movement in Spain and Sicily had transferred Arabic scientific knowledge into Latin. Works of Al-Khwārizmī (as Algoritmi), Al-Farghānī (Alfraganus), Al-Battānī (Albategnius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), and many others became available to European scholars. These translations reintroduced lost Greek knowledge and the original contributions of Muslims. For example, Al-Khwārizmī’s algebra became the standard textbook in Europe (his book was translated by Robert of Chester in 1145), teaching Europeans how to solve equations systematically. The Hindu-Arabic numerals and decimal system replaced cumbersome Roman numerals in Europe largely due to Latin translations of works like Al-Khwārizmī’s On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals. By the 13th century, Leonardo Fibonacci championed these “Arabic numerals” in Italy after learning of them from North African teachers, and their adoption revolutionized commerce and science in the West. With this new numeric system, Europeans could perform calculations with an ease and scope previously impossible, paving the way for advances in engineering, bookkeeping, and later, calculus.

In astronomy, the impact is even more direct. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), who ushered in the heliocentric model, acknowledged his debt to Muslim astronomers. In his major work De revolutionibus, Copernicus cites Al-Battani by name at least two dozen times, referencing Al-Battani’s precise observations of planetary positions and solar motion. He also mentions other Islamic scholars like Thābit ibn Qurra, Al-Zarqālī (Arzachel), and Al-Bitrūjī (Alpetragius). Al-Zarqālī’s tables of solar motion and his invention of the astrolabic quadrant influenced Copernicus’s own calculations of planetary orbits. Furthermore, modern historians have found that Copernicus’s mathematical techniques in modeling planetary orbits – for instance, his solution to replace the Ptolemaic equant – bear a striking similarity to those developed by the Maragha school (Al-Tusi and his student Qutb al-Din al-Shīrāzī) and by Ibn al-Shātir in Damascus. Copernicus used combinations of epicycles that mirror the Ibn al-Shātir models for Mercury and the Moon, suggesting that he (or intermediary sources) had access to or was inspired by those Islamic models. While it’s debated how directly this knowledge was transmitted, the parallels indicate that the Islamic critique and refinement of Ptolemaic astronomy significantly smoothed the path for the Copernican revolution.

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), who formulated the laws of planetary motion, also benefited from Islamic precedents. Kepler’s work was built upon the accurate astronomical data of Tycho Brahe – data which in turn was the culmination of observation techniques honed over centuries, starting with the meticulous star catalogs of Ulugh Beg (15th-century Samarkand) which surpassed those of the ancient Greeks in accuracy. Additionally, Kepler’s investigations into optics (e.g. the inverse-square law of light) cite the legacy of Ibn al-Haytham’s optical research. More indirectly, Kepler’s fascination with geometric harmony in planetary orbits (his Mysterium Cosmographicum) can be seen as part of a long tradition of seeking mathematical harmony in the heavens – a tradition kept alive by Muslim astronomers who strove to reconcile Plato, Ptolemy, and the Quran’s view of an orderly cosmos.

Finally, in mathematics, the contributions of Islamic scholars were indispensable to the later development of calculus by Newton and Leibniz in the 17th century. Newton and Leibniz’s genius lay in synthesizing earlier mathematical ideas (algebra, geometry, and the concept of infinitesimals) into the formalism of calculus. Those earlier ideas were significantly shaped by medieval Islamic mathematics. The very algebraic symbolism and algorithms (Cartesian algebra) that Newton and Leibniz used to express calculus had its roots in Al-Khwārizmī’s algebra and Al-Karajī’s theory of polynomials. As Britannica notes, “The essential insight of Newton and Leibniz was to use Cartesian algebra to synthesize earlier results and develop algorithms…” – and those earlier results included the decimal arithmetic and algebraic methods transmitted from the Islamic world. Muslim mathematicians also made some early forays into infinitesimal techniques: in the 10th century, Abū’l-Hasan al-Uqlīdisī and later Jamshīd al-Kāshī (15th c.) explored decimal fractions and iterative methods that foreshadow numerical integration; and as early as the 11th century, Ibn al-Haytham summing powers of integers (to find formulas for sums of squares and cubes) was effectively doing an early form of integration. Thābit ibn Qurra had even worked on what we might call an early calculus problem – determining the volume of a paraboloid by summing infinitesimal slices – a method that would much later resemble Cavalieri’s principle. It’s striking that “Muslim scientists such as Thābit ibn Qurra and Ibn al-Haytham wrote about calculus” long before Newton. While their efforts were not unified into a general theory, they provided important building blocks. Additionally, in physics, ideas of inertia and momentum from Islamic polymaths like Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) and al-Baghdādī were precursors to Newton’s laws of motion. Thus, Islamic thought created an undercurrent of mathematical and physical knowledge that the architects of modern science could draw from. Newton’s famous quote “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” is apt – among those giants were the likes of Al-Khwārizmī, Al-Tusi, and Ibn al-Haytham.

In conclusion, the Islamic Golden Age’s integrative approach – taking inspiration from Quranic verses and values to pursue scientific knowledge – led to remarkable advances in astronomy and mathematics. These advances were not only crucial for the Islamic civilization’s own needs (such as worship, navigation, and timekeeping) but also formed a conduit through which classical knowledge was preserved and enhanced, then passed on to others. The Quran acted as an intellectual spark, instilling in scholars a sense of purpose and confidence that the universe was intelligible and harmonious. As a result, medieval Muslim scholars achieved a synthesis of faith and reason, producing scientific works that would illuminate the world. Their legacy in astronomy and mathematics dramatically advanced human civilization – from enabling accurate calendars and navigation to laying foundations for Renaissance astronomy and even the eventual emergence of calculus and modern science. The story of Islamic science is thus a prime example of how religious ideas about order and knowledge can fuel a Golden Age of discovery, echoing down to our present day in the very way we chart the heavens and calculate our world.

Sources:

Wikipedia, “Astronomy in the Islamic World” (European influence)en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

The Glorious Quran – Surah Yunus 10:5, Surah Ar-Rahman 55:5, Surah Al-Anbiya 21:33, etc., translation and commentary thequran.love.

Ziauddin Sardar, The Quranic Verses about Math and Astronomy thequran.love.

Zakaria Virk, “Muslim Contributions to Mathematics and Astronomy” – Review of Religions reviewofreligions.org.

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science – Algebra and Mathematics in Medieval Islam en.wikipedia.org.

Astronomy in the Medieval Islamic World – Wikipedia en.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org.

Library of Congress, Islamic Astronomy exhibit thequran.love.

Wikipedia, “Nasir al-Din al-Tusi” en.wikipedia.org, “Qibla”en.wikipedia.org, “Al-Khwarizmi” islamic-study.org.

Teach Mideast, Islamic Science: The Astrolabe (on Quranic inscriptions and uses of astrolabes) metmuseum.org teachmideast.org.

The Muslim Contribution to Optics – Fountain Magazinefountainmagazine.compmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

The Muslim Vibe, “Influence on Newton’s Scientific Breakthrough”themuslimvibe.com.

Britannica, “Mathematics: Newton and Leibniz” britannica.com.

Leave a reply to Can Javed Ghamidi Supplement My Work and Can I Return the Favor: You be Judge? – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply