Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832), the most celebrated philosopher of Germany, once said: “As often as we approach the Quran, it always proves repulsive anew; gradually, however, it attracts, it astonishes, and, in the end forces admiration.” What happened to Goethe is experienced by many others as well because the Quran is not a typical literature genre that we are used to. Sometimes the critics highlight that they find so many repetitions in the Quran. They fail to appreciate the profound purpose behind the repetitions. One common theme in the Quran is that God draws attention of the reader to something that he or she can perceive by sight or in that sense is tangible and from that He argues for the intangible, His creativity, His divinity or imparts some intellectual, moral or spiritual message.

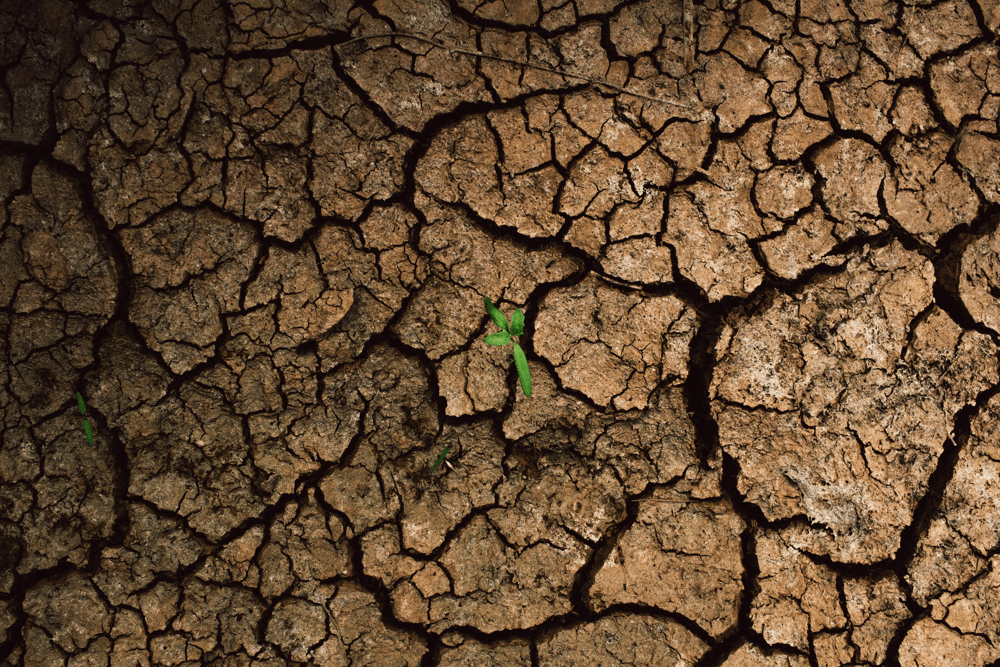

The Glorious Quran frequently speaks of dry land and how after rain it yields greenery, foliage, flowers and fruits and from this tangible observation takes us to intangible inferences as you will see in the passages below.

Introduction

The Quran often invites people to reflect on the natural world as a testament to Allah’s existence and greatness. Ordinary phenomena like the cycle of day and night, the stars, and the rain are described as ayat (signs) that point beyond themselves to the Creator. Among these, the burst of greenery and plant life after rainfall is a particularly vivid metaphor. In the Quran’s discourse, the transformation of a dry, “dead” earth into a lush carpet of life is not only evidence of Allah’s power to create and sustain, but also a lesson imbued with spiritual and moral insight. As one verse states: “And Allah has sent down rain from the sky and given life thereby to the earth after its lifelessness. Indeed in that is a sign for a people who listen.” In a single image, the Quran directs our minds from the refreshment of parched soil to the reality of a Merciful Provider behind it all.

The significance of rain and greenery in the Quran goes far beyond mere physical rejuvenation of the land. Deserts blooming after showers or fields ripening with crops are presented as reminders of Allah’s mercy and creative power, “signs for those who use reason.” The sudden bloom of life in a once-arid land stirs a sense of wonder – exactly the response the Quran seeks to cultivate as it links natural revival to profound truths. These natural signs function as parables: they hint at Allah’s ability to resurrect the dead, they illustrate the transient beauty of worldly life, and they inspire gratitude and humility in the observer. This article will explore key Quranic verses that highlight greenery after rain, unpack their theological lessons, examine classical and modern interpretations, analyze the original Arabic expressions, and consider scientific insights that further illuminate how plant growth serves as a metaphor for resurrection, morality, and divine wisdom.

Quranic Verses on Greenery and Growth After Rain

The Quran contains numerous verses where Allah draws human attention to the rain and the ensuing plant life. These verses are often vivid and poetic, yet clear in their message. Below is a collection of key Quranic quotes (in translation) that highlight how rainfall brings forth greenery and what lessons we are meant to draw from this phenomenon:

- Surah Al-Hajj 22:63 – “Do you not see that Allah sends down rain from the sky, then the earth becomes green? Surely Allah is Most Subtle, All-Aware.” This verse points to the almost miraculous greening of the earth as a direct result of Allah’s sending of rain, emphasizing His intimate knowledge and gentle power in nurturing life.

- Surah Ar-Rum 30:50 – “So observe the effects of the mercy of Allah – how He gives life to the earth after its death. Indeed, that [same One] will give life to the dead, for He is over all things competent.” Here “the mercy of Allah” refers to rain. The verse explicitly makes the analogy between reviving dead land and resurrecting dead people, urging observers to see a preview of resurrection in every rainfall.

- Surah Fussilat 41:39 – “And of His signs is that you see the earth stilled (bare); but when We send down upon it water, it quivers and grows. Indeed, He who has given it life is the Giver of life to the dead. Indeed, He is over all things competent.” This verse uses striking imagery – the quaking and swelling of soil – to describe the earth coming alive. It then draws the logical conclusion: the One who revives the land can surely revive dead humans.

- Surah Az-Zukhruf 43:11 – “And He is the One who sends down rain from the sky in perfect measure, with which We give life to a dead land. Similarly, you will be brought forth (from the dead).” This verse highlights the precision (“in perfect measure”) of the rainfall and ties the scene of a once-dead land now teeming with life directly to human resurrection in the hereafter.

- Surah Yunus 10:24 – “The example of the life of this world is like rain which We send down from the sky. The earth’s vegetation absorbs it, then it becomes lush and green, then (after a time) it dries up and breaks into pieces, scattered by the winds. And Allah is fully capable of all things.” This verse presents a parable: our worldly life, with its growth and decay, is likened to the brief blooming of plants after rain before they wither. It’s a cautionary image about the temporary nature of worldly splendor.

- Surah Al-Hadid 57:20 – “Know that the life of this world is but play and amusement, adornment and mutual boasting among you, and competition in wealth and children – like the example of rain that produces vegetation which pleases the farmers; then it dries so that you see it turn yellow, then it becomes chaff. And in the Hereafter is severe punishment (for the heedless) and forgiveness from Allah and His pleasure (for the righteous). For the life of this world is nothing but a deceiving enjoyment.” This verse explicitly uses the rain/plant growth cycle as a metaphor to contrast short-lived worldly beauty with the enduring consequences of the Hereafter, urging us not to be misled by life’s temporary charms.

These verses (and many others in the Quran) weave a consistent tapestry of meaning: rainfall is a mercy from Allah that brings forth life, and this natural revival is set forth as evidence of divine power and wisdom. The imagery of greening earth appears in contexts affirming faith in Allah’s lordship and the coming Resurrection, as well as in contexts imparting moral lessons about gratitude and perspective. In the next sections, we will delve deeper into what theological and spiritual lessons Muslims have derived from these verses, how classical and contemporary scholars have interpreted them, the nuances of the original Arabic wording, and how modern science resonates with these timeless metaphors.

Theological and Spiritual Lessons

The motif of rain and vegetation in the Quran is rich in theological significance. First and foremost, these verses affirm core attributes of Allah: His existence, creative power, and mercy. No one but an all-powerful God could send life-giving rain from the sky and orchestrate the intricate process by which a barren land blooms. Thus, when the Quran says “look at the results of Allah’s mercy” in the revived earth, it is inviting us to recognize that this natural phenomenon is not automatic or random – it is an act of divine mercy. The timely coming of rain and the revival of crops testify to Allah’s providence (He is ar-Razzāq, the Provider) and His compassion toward His creatures. People instinctively rejoice at rain after a drought, and the Quran reminds us that this joy should translate into remembering and thanking the One who sent it.

A central theological lesson drawn explicitly in the Quran is the link between natural revival and resurrection of human beings. Those who doubt life after death are directed to observe the “dead” earth brought back to life: “He Who gives life to the dead earth can surely give life to the dead (humans).” Classical scholars like Ibn Kathir explain that Allah uses the example of reviving the land to “draw attention to the revival of people’s bodies after they have disintegrated.” Indeed, Ibn Kathir and others quote the Quran’s refrain: “Similarly, We shall raise up the dead.” In his commentary on this theme, Ibn Kathir writes: “Similarly, We shall raise up the dead – meaning, just as We bring life to dead land, We shall raise up the dead on the Day of Resurrection, after they have disintegrated.”

He even notes a report that Allah will send down rain in the Hereafter and human bodies will sprout from the earth like plants. Such commentary underscores how firmly the resurrection analogy was understood in Islamic tradition. The message is clear: the One who revives gardens from dust can just as easily revive human beings from their graves. Every rainstorm, then, is a reminder of the coming Resurrection and a call to prepare for it.

Beyond proving Allah’s power, these verses carry moral and spiritual lessons for our daily lives. One lesson is the temporary nature of worldly life. The Quran repeatedly uses the growth-then-decay cycle of plants to illustrate that the beauty and vigor we enjoy now will inevitably fade. Just as a field of wildflowers blooms after spring rain only to dry up by summer’s end, our youth, beauty, and worldly assets are transient. “The life of this world is like the rain…then it dries up and turns yellow…”

This parable urges us not to become enamored by material success or pleasures – they are as fleeting as spring greenery. Instead, the believer should focus on that which is everlasting (the afterlife, and Allah’s pleasure). By reflecting on the fate of plants, we learn humility and avoid arrogance about our own short-lived achievements.

Another key lesson is the need for gratitude and remembrance of Allah. Rain is described as a gift that revives the earth for our sustenance. Crops, fruits, and pastures emerge that feed humans and animals. The Quran says, “Out of it (the rain) We bring forth growth of every kind – produce and green foliage and clustered grain and fruits…”

All of this is given as “provision for Our servants.” The moral implication is that we should be thankful to Allah for these blessings of food and life. In Surah Ya-Sin, after mentioning how humans eat from what Allah causes the earth to grow, the Quran asks, “Will they not then give thanks?” (36:33-35). Failing to acknowledge the Provider behind our nourishment is a spiritual blindness the Quran warns against. Thus, every meal and every green blade of grass is meant to remind us of Allah’s generosity, prompting us to remember Him (through prayers and praise) and not take His sustenance for granted.

Rain and greenery also provide a lesson in hope and the possibility of spiritual renewal. Just as the earth can appear utterly dry and lifeless – cracked soil with nothing growing – yet can suddenly be softened and revived by a downpour, so too can a human heart that has grown hard or a community that has fallen into spiritual drought be revived by Allah’s guidance. The Quran subtly makes this connection. In Surah Al-Hadid, Allah asks rhetorically if the time hasn’t come for believers’ hearts to soften to the truth, warning against hardening of hearts. Immediately after, in the same context, it says: “Know that Allah gives life to the earth after its lifelessness – We have made the signs clear for you, so perhaps you will understand.” (57:16-17). The juxtaposition is striking. Classical commentators note that this is an allusion to hearts becoming soft and alive with faith after being hard and “dead.” A modern writer draws the analogy clearly: “Just like rain can soften dead earth, the Quran can soften dead hearts.”

In other words, divine revelation is to the soul what rain is to the soil – a source of life. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) also used this analogy in a famous hadith, comparing the guidance he brought to rain that falls on different types of ground (some fertile, absorbing water and bringing forth abundant vegetation, and some barren, yielding nothing). The implication for us is inspiring: no matter how spiritually barren one’s heart may feel, it can be revived. Just as seemingly dead seeds sprout with a bit of water, a heart can sprout faith with a drop of Allah’s mercy. This gives the believer hope in Allah’s forgiveness and the potential for personal reform. It also teaches us to be patient and optimistic when we do good or share guidance with others – the “rain” of guidance may take time to show results, but the bloom will come.

Finally, these verses inspire an attitude of awe and mindfulness. Witnessing the marvel of nature’s rebirth is meant to make us “mindful” (Quran 7:57 ends with “Perhaps you will remember/ take heed”). When a believer sees dark clouds roll in after a long dry spell, or green shoots pushing up after rain, it should trigger remembrance of Allah and an acute awareness of one’s dependence on Him. The Quranic description of joyful farmers and herders after rain is essentially an invitation for all of us to feel and express that joy toward Allah. Spiritually, this fosters tawakkul (trust in Allah). We learn that just as Allah can send rain to rescue a withering land, He can send relief for any problem in our lives. The earth’s revival is almost a metaphor for Allah’s intervention and sustenance in all things – a reason to trust and not despair.

In summary, the greening of the earth after rain, as portrayed in the Quran, is packed with lessons: it confirms Allah’s power over life and death, it prefigures our resurrection, it relativizes the glitter of this world, it calls for gratitude and humility, and it offers hope that Allah’s grace can revive hearts and communities. It is little wonder that classical Muslim scholars eagerly expounded these themes, and that believers to this day draw spiritual strength from the simple act of watching rain fall on the earth.

Classical and Modern Interpretations

Given the rich meanings outlined above, Quranic commentators of both the past and present have not overlooked the motif of rain and vegetation. Classical tafsir (exegesis) works devote attention to these verses, often highlighting the resurrection parallel and expanding on the imagery, while modern reflections sometimes bring new angles, such as environmental awareness or scientific awe. Let’s explore how scholars like Ibn Kathir, Al-Tabari, and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi understood these verses, and how contemporary writers relate them to today’s context.

Classical scholars unanimously see the revival of dead land as one of the timeless proofs of Resurrection. In the 14th-century commentary of Ibn Kathir, for example, the verse “Look at the effects of Allah’s mercy, how He gives life to the earth after its death” (30:50) is cited and then Ibn Kathir comments: “Verily, He who revives it (the earth) is the One who shall indeed raise the dead, for He is Able to do all things.”

Likewise, for Quran 7:57 (“We drive [the clouds] to a dead land and bring forth with it vegetation… Thus We will bring forth the dead”), Ibn Kathir explicitly writes: “Just as We bring life to dead land, We shall raise up the dead on the Day of Resurrection, after they have disintegrated.”

Al-Tabari (9th-century) before him had made similar remarks, emphasizing that Allah “gives life” to hearts and people just as He does to soil. In his tafsir, Tabari often points out the logical syllogism presented by these verses: if Allah can do X (a phenomenon you witness), then surely He can do Y (which you doubt). The early Muslims took this argument very seriously, considering it a decisive reply to those who denied resurrection. In fact, Quran 29:63 notes that even the pagan Meccans would acknowledge Allah sends down rain and revives the earth, yet the Quran asks how they can then deny His power to revive them after death.

Another aspect classical commentators address is Allah’s wisdom and mercy in the process of sending rain. They sometimes give almost scientific details in the tafsir, derived from observation and reports. For instance, commenting on verses like 30:48 (which describes winds driving clouds), Ibn Kathir describes how winds carry vapors, clouds form and are guided to a land, and then rain falls by Allah’s command. He notes the joy of people when rain finally arrives after despair, an experience desert-dwelling audiences knew well. Such observations in classical tafsirs show that Muslim scholars saw no conflict between explaining the natural mechanism and extolling Allah’s hand in it – the mechanism itself was a sign of divine design. Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (12th-century) in his Mafatih al-Ghayb (Keys to the Unseen) often philosophizes about these signs. While we don’t have a direct quote here, Razi was known to delve into questions like: Why does the Quran mention certain stages of rain formation? What is the deeper hikmah (wisdom)? He and others note the precise wording – for example, Allah sends rain “in due measure,” which preempts floods and damage, and this reflects Allah’s Qadar (Measure) and mercy. They also take the greening of the earth as an illustration of Allah’s attribute Al-Muhyi (The Giver of Life).

Classical tafsirs frequently draw additional moral analogies. As seen above, Ibn Kathir connects these verses to the famous hadith likening guidance to rain – thereby reinforcing that a “good heart” is like fertile soil, absorbing wisdom and producing righteous deeds. Some exegetes like Al-Qurtubi also highlight the aspect of gratitude: when Quran 16:65 says “indeed in that is a sign for those who listen,” “listening” is interpreted as heeding the call to thank Allah for His sustenance. The classical scholar Al-Razi adds a linguistic insight: the verse says it is a sign for “those who listen,” implying that merely hearing these words and reflecting should stir a response, unlike the deaf-hearted who ignore such signs.

Moving to modern interpretations, we find that contemporary scholars and writers often reinforce the classical lessons but also relate these verses to current issues and sensibilities. For example, modern Islamic teachers emphasize an environmental consciousness gleaned from these verses. They argue that since Allah repeatedly directs our gaze to the wonders of nature – rain, plants, fruits, bees, and so on – a Muslim should develop a deep appreciation and respect for the natural world. The logic is that nature is a living sign of Allah, so caring for it (preventing pollution, wastage, and environmental destruction) is akin to respecting Allah’s signs. Some even point to the Quran’s subtle ecological balance: rain comes “in due measure,” and the earth produces its provision, suggesting that humans too should maintain balance and not upset the harmony. In an era of climate concern, these Quranic reminders carry fresh relevance. A Muslim environmentalist might quote, “Corruption has appeared on land and sea by what people’s hands have wrought” (30:41) right alongside the verses of Allah’s nurturing of the earth, to advocate for responsible stewardship.

Modern writers also use these verses to inspire spiritual reflection in a fast-paced world. A contemporary article might encourage readers to take a break from technology and observe a garden after rain, linking it to Quranic verses to rejuvenate one’s faith. The idea of tadabbur (deep contemplation) on nature as a means of reconnecting with the Quran is gaining traction. For instance, one writer describes watching a landscape turn green after rainfall as an “iman-boosting experience” that reaffirms closeness to Allah. Such reflections show how the Quran’s imagery remains powerful today – anyone who has seen a parched lawn spring back to life after rain has essentially witnessed an ayah (sign) in real time.

Another modern angle is to highlight the diversity and beauty of life that rain produces as a sign of Allah’s artistry. As one author notes, from the same water Allah brings out an endless variety of plants: the cereals, fruits, vegetables and flowers that enrich our world. This invites a sense of wonder at biodiversity. Each species has its own color, fragrance, and purpose, yet all are sustained by the same simple rainwater. This diversity, modern commentators say, reflects Allah’s wisdom in creation – and it can foster a greater appreciation for conserving the varied forms of life on earth (tying back to environmental ethics).

Modern scientific-minded commentators often remark on how these Quranic verses “anticipated” or align with scientific knowledge. For example, the description in Surah Rum 30:48-50 of the water cycle (winds driving clouds, fragmented clouds yielding rain) is noted for its accuracy. In the past, people had various myths about rain, but the Quran set forth a clear, orderly description that today’s meteorology confirms. This has been highlighted in works like Maurice Bucaille’s The Bible, The Qur’an and Science and other Islamic literature, not to claim the Quran as a science textbook, but to argue that its information is perfectly compatible with scientific truth and thus divinely inspired. A contemporary scholar might say: “Allah’s description of how He ‘spreads’ the clouds and makes rain fall matches what we see on satellite images – an eloquent convergence of revelation and reality.”

In summary, classical interpretations of the rain and greenery verses center on theological proofs (especially Resurrection) and moral guidance (gratitude, faith, humility), often enriched with linguistic and prophetic anecdotes. Modern interpretations uphold those views and additionally connect these verses to broader themes like environmental stewardship, interfaith understanding of religion and science, and personal spiritual growth in the modern context. Both classical and modern perspectives together show the remarkable depth of these short Quranic references – they speak to the intellect, the soul, and even to our role as custodians of Earth.

Linguistic Analysis of Key Terms and Imagery

To fully appreciate the impact of these Quranic verses, it helps to examine some of the key Arabic terms and the rhetorical devices employed. The original Arabic is rich and layered, often packing multiple shades of meaning into a single word. Let’s look at a few important terms and phrases: ihyā’ (revival), samāwāt (heavens/skies), barakah (blessing/abundance), and some of the descriptive imagery words used for the earth’s revival.

- “Ihyā’” (إحياء) – This noun (and its corresponding verb yuhyi, “He gives life”) comes from the root ḥ-y-ā which means life. In the verses, we see phrases like ahyaynāhā (We gave it life) in reference to the earth. For example, “fa-aḥyaynā bihi l-arḍa ba‘da mawtihā” – “then We give life thereby to the earth after its death.” The choice of the word life (instead of, say, “We make it wet” or “We cause plants to grow”) is deliberate and powerful. It essentially personifies the earth as something that dies and lives. Theologically, this underscores that life itself is a gift from Allah – whether it’s the life of a plant or a human. The recurrence of ihyā’ ties the theme of botanic growth to the concept of resurrection (literally “re-lifing” the dead). Arabic linguists point out that using mawt (death) and ḥayāt (life) for land is a vivid metaphor; it makes the lesson of resurrection more concrete, as if the soil itself experiences a tiny “resurrection” with each rain. The term al-Muḥyi (The Giver of Life) is one of Allah’s divine names, and these verses display that attribute in action. Interestingly, ihyā’ is also used in Quran 2:56 when Allah “gave life” to people who had died, and in many other places about raising the dead – strengthening the conceptual link across the Quran.

- “Samā’ / Samāwāt” (سماء / سماوات) – These words mean “sky, heaven.” As-samā’ in singular often refers to the sky above us (or rainclouds by extension), while as-samāwāt in plural is typically “the heavens” (which in Islamic cosmology are seven layers high). In the verses about rain, the singular is commonly used: “Allah sends down water from the sky*” (اللَّهُ أنزلَ مِنَ السَّماءِ ماءً). The use of samā’ is interesting because in ancient Arabian understanding, the sky/heaven was seen as the source of rain – literally water falling from the heaven. By saying Allah sends water from samā’, the Quran is asserting Allah’s control over the cosmic domain above as well as the earth below. The word samā’ also carries a sense of loftiness and grandeur (its root relates to “being high”). So rain is depicted as something that comes from a high, divine realm down to the lowly earth. This reinforces the idea of rain as a gracious gift from above, not a mundane occurrence. In several verses, the phrase min as-samā’ (from the sky) is paired with rizq (provision) or barakah (blessing), emphasizing that sustenance is decreed by Allah from the heavens. Another subtlety: in 30:48, mentioned earlier, the verse says Allah “spreads [the clouds] in the sky (as-samā’) as He wills”. Here as-samā’ could mean the atmospheric expanse. Linguistically, the plural samāwāt (heavens) in other contexts reminds believers that there are entire realms of creation above – so the rain coming from the samā’ hints at a vast unseen system Allah controls. In summary, samā’ in these verses isn’t just “sky” in a banal sense; it connotes the higher agency of Allah delivering mercy from on high.

- “Barakah / Mubārak” (بركة / مبارك) – Barakah means blessing, abundance, or an increase of goodness. In the context of rain and plants, the Quran uses the adjective mubārak (blessed) to describe water. Surah Qāf 50:9 is an example: “We sent down blessed water (mā’an mubārakan) from the sky, and with it produced gardens and grain for harvest.” Describing rainwater as “blessed” indicates that it is filled with khayr (goodness) and produces plentiful benefits. The concept of barakah carries the idea of something small yielding far more than expected. Indeed, a few millimeters of rain can transform miles of desert – a small cause with a disproportionately large effect, which is exactly what barakah implies. In Arabic, barakah can also mean a stable, continuing goodness (its root is related to the idea of something that remains in place, like how a camel kneels and stays). Rain is “blessed” because it leaves lasting effects: filling aquifers, sprouting seeds that may become a years-long orchard, etc. By calling water mubārak, the Quranic text subtly teaches that this is not a trivial thing but a vehicle of divine grace. Classical commentators often say mubārak here means “containing abundant benefit.” There is also a linguistic beauty: the sound of mubārak might evoke birka, a pool – hinting at the pooled water of rain that collects as a blessing (though this is more a mnemonic than etymology). In any case, every drop of rain is depicted as carrying barakah, which should instill a sense of appreciation and even sanctity for water in the believer’s heart.

- Imagery of the Earth’s Revival – The Quran doesn’t limit itself to abstract terms; it paints pictures with words. Two verbs in particular stand out: “ih’tazzat” (اهتزت) and “rabat” (ربت). These appear, for example, in Surah Al-Hajj 22:5: “…you see the earth ihtazzat wa rabat (trembling/quivering and swelling), and it produces every lovely kind of growth.” Similar wording is in 41:39 and 16:65 (with slight variations). The verb ih’tazza means to shake, stir, or quiver. It conjures the image of the ground stirring to life – as if the soil itself shivers with excitement at the falling rain. Some classical scholars explained this as the land’s response when rain penetrates it – perhaps referring to how soil particles separate or how sprouts break through, causing the surface to shift. The verb rabat means to swell, rise, or grow. After soaking up water, the earth “puffs up” as seeds germinate beneath and push upward. Modern translators render these as the earth “thrills and swells,” or “stirs and swells.” The choice of these words is highly poetic and emotive. It gives life to the scene and allows the reader/listener to almost feel the motion of growth. In Arabic, the phonetic quality of ih’tazzat – those two emphatic “T” sounds – can even mimic a staccato vibration, while rabat with its drawn “a” sound feels like an expansion. Thus the Quran employs onomatopoeic and descriptive language to capture the miracle of growth. This imagery not only makes the verses memorable, but it reinforces the theme: the “dead” earth is truly coming alive, moving and changing, by Allah’s command. It adds weight to the argument that resurrection of human life is analogous – just as the seemingly inert ground can move and produce life, so can decomposed human remains be made to live and move again. Furthermore, the phrase “of every beautiful kind” (min kulli zawj bahīj) follows these verbs. Bahīj means splendid, delightful, cheerful in appearance – indicating the vibrant colors and pleasing nature of the plants that grow. The Quran is drawing not just on the fact of growth but the aesthetics of it. The greening earth isn’t just useful, it’s beautiful, reflecting Allah’s attribute of al-Jamīl (The Beautiful) who loves beauty. Linguistically, zawj (kind/pair) here can also remind the reader that plants reproduce in pairs or that there are many species – a hint of the botanical diversity created from the one rain.

- “Zahrat al-ḥayāt al-dunyā” (زهرة الحياة الدنيا) – While not in the verses quoted above, this phrase appears in Quran 20:131 meaning “the flower (bloom) of the worldly life”. It uses zahra (flower) as a metaphor for the fleeting beauty of dunya (world). It resonates with the rain motif: our worldly enjoyments are like a flower – they blossom brightly but briefly. The use of zahra underscores how something can be gorgeous but short-lived. It’s linguistically related to zuhr (noon) – the brightest time of day that soon declines. So, when the Quran talks about plant life, it often chooses terms that double as metaphors for ephemerality and splendor.

In examining these terms, we see how the linguistic choices amplify the message. Ihyā’ makes the analogy to resurrection explicit; samā’ raises our eyes heavenward to recognize the source of mercy; mubārak casts rain as a sacred bounty rather than a mundane event; ih’tazzat wa rabat animate the soil in our imagination, making the lesson visceral; bahīj and zahra emphasize beauty laced with transience. The Quran’s eloquence lies in such details – a few well-chosen words evoke entire concepts and sensations. This is why classical scholars like Razi would sometimes spend pages on a single word, unpacking its implications. The net effect on a receptive heart is that reading these verses is not a dry experience; it’s almost as if you can smell the damp soil, see the green shoots, and feel the moral it conveys. The language itself thus serves the spiritual purposes of the verses, engaging both mind and soul.

Scientific Insights on Plant Growth as a Metaphor

One of the remarkable aspects of the Quran’s references to nature is how accurately and timelessly they describe phenomena that we can now examine through science. The cycle of rain and plant growth is no exception. Modern scientific insights not only confirm the Quran’s descriptions but also deepen our appreciation for the metaphor of revival and the wisdom behind it. Let’s explore a few scientific angles: the water cycle and rainfall, the germination of seeds and revival of ecosystems, and how these can analogously strengthen the plausibility of resurrection and the moral themes the Quran draws.

Rainfall and the Water Cycle: Today, we understand that water on earth goes through a continuous cycle – evaporation from oceans and land, formation of clouds, and precipitation (rain/snow) falling back to earth. The Quran alludes to key stages of this process. Surah Ar-Rum 30:48, for example, describes how winds drive clouds, then they are spread out and fragmented, and then rain falls – which is a succinct summary of cloud formation and rainfall distribution. Verses like “He sends the winds as heralds of His mercy” (7:57) match the scientific fact that wind patterns often precede weather changes and carry moisture. The idea of “rain in due measure” reflects how precipitation is constrained by atmospheric conditions – too heavy and it would destroy, too light and it would not suffice, but Allah balances it. Science has quantified these measures: for instance, there is an average annual rainfall globally, and even slight shifts can cause floods or droughts. The Quran’s wording hints at this fine-tuning.

From a scientific perspective, we also marvel at how rainwater is ideally suited to its life-giving role. Pure rainwater (especially after condensation) is free of the high mineral content that might inhibit plant growth; it’s often slightly acidic which helps release nutrients in the soil. The Quran says “We send down pure water from the sky” (25:48). Modern meteorology explains that rain forms around tiny particles (aerosols) in clouds, and by the time it falls, it has a purity and softness that truly rejuvenates soil life. These nuances might not be explicitly stated in the Quran, but they underline the title “mercy” given to rain. Scientists also note how rain is part of a larger climate system that maintains life on Earth by cycling water. Without this cycle, nutrients wouldn’t be distributed, temperatures would soar, and life would be scarce. The Quran’s concise references manage to capture the essence: wind, cloud, rain, growth – it is scientifically spot-on and complete in cycle, which many a believer sees as yet another sign that the Author of the Quran is the Creator of nature itself.

Seed Germination and Ecosystem Revival: Perhaps the most striking scientific insight relative to our discussion is how seeds and ecosystems can lay dormant and then rapidly come to life with rain. In deserts like the Atacama or arid regions of Arabia, it is observed that after a significant rain, an explosion of wildflowers and plants occurs within days. Botanists explain that many desert plant seeds have dormancy mechanisms – tough shells or special hormones – that prevent them from germinating until sufficient water is available. They can literally survive in dry soil for years. When rain finally saturates the ground, it triggers a process called imbibition, where seeds absorb water. Scientifically, this causes the seed to swell, the seed coat to soften or crack, and activates enzymes that kickstart metabolism. The embryo inside the seed then begins to grow, using stored food to push out a root and a shoot. This is precisely when “the earth quivers and swells” as the Quran describes. The pressure of emerging roots can shift soil particles; one could say the ground “moves.” Even on a microscopic level, soil rich with dormant microorganisms becomes active – bacteria and fungi start processing nutrients once water is present, releasing gases that can make the soil literally heave slightly. The term ih’tazzat (quiver) captures this dynamic well. Science has given imagery to this: time-lapse photography of seedlings shows the soil bulging and little clods upheaved as the sprout ascends.

The speed and abundance of plant growth after rain can be astonishing. A modern example: Chile’s Atacama Desert, known as the driest place on earth, occasionally experiences a “super bloom” when higher-than-usual rain falls. In 2017, after unexpected rain, scientists documented the desert floor carpeted with thousands of flowers of various colors. Locals call it desierto florido – the flowering desert. Similarly, in the Arabian deserts, pastoral nomads historically moved and rejoiced when rains brought up pastures for their camels and sheep almost out of nowhere. This real phenomenon backs the Quran’s repeated reference to how quickly and lavishly life springs forth by Allah’s command.

From an ecological standpoint, rain doesn’t just grow isolated plants; it restarts entire food chains. Grass grows, which allows herbivores to graze, which feeds predators, etc. Buried eggs of insects might hatch when rain moistens the ground, adding to the burst of life. Puddles become breeding grounds for frogs. The whole ecosystem “resurrects.” Scientists see this as adaptations to periodic rainfall. Believers see, in addition, the wisdom of a Creator who made life resilient and hope ever-present. Even when an environment looks utterly devoid of life, Allah has implanted potential life (in seeds, spores, eggs) waiting for the right moment to shine. This power of resurgence reinforces the Quranic analogy: if Allah has packed the earth with hidden potentials that revive with a bit of water, what about the human body and soul? Could He not make hidden potentials in our dust that will respond and revive when He commands “Be” on Judgment Day? From a biological view, human resurrection is beyond current scientific explanation, but these analogies make it conceptually easier to grasp. A seed far beneath a rock can sprout after years – a human soul, in Allah’s care, can certainly be given a new body after centuries. The Quran asks us to use reason in this way, and science provides plenty of analogies of things that seemed dead but were not irreversibly so.

Alignment with Modern Science and Reinforcement of Quranic Themes: Modern soil science also tells us that when rain falls, it triggers chemical and physical processes that rejuvenate the earth. Dry, compacted soil absorbs moisture and becomes looser (swells), allowing air to penetrate; nutrients that were crystallized in dry heat dissolve into forms plants can uptake. It’s a comprehensive renewal. The Quran’s choice of calling rain “rahmah” (mercy) is thus perfectly apt – without it, lands turn literally unmerciful (famine, dust storms, etc.), but with it, there is mercy for all creatures. We might also consider the role of “measured rain” from a scientific angle: If all the year’s rain fell at once, it would cause chaos. Instead, Allah distributes it over seasons and places. The Quran in Surah Al-Mu’minun 23:18 says, “We send down water from the sky according to [due] measure, and We cause it to soak in the earth – and indeed, We are able to take it away.” This resonates with today’s knowledge of how freshwater resources are limited and how delicate the balance is. It’s a sober reminder in an age of climate change that if rainfall patterns shift drastically, no technology can fully avert disaster – we remain at Allah’s mercy, as do our crops. Scientists, while secular in approach, indirectly echo this by highlighting how dependent civilization is on stable rainfall and how powerless we are to create rain on our own (cloud seeding has limited effect and carries risks). Ultimately, rain is a gift we cannot replace.

Science has also illuminated how plants “know” to die and regrow in cycles, which underscores the Quranic moral of worldly life’s ephemerality. Annual plants have genetic programming to sprout, bloom, seed, and then die within a season – leaving seeds for the next generation. It’s as if they are designed to demonstrate the cycle of life, death, and rebirth yearly. Perennial plants may wither their leaves in drought and appear dead, but the moment they get water, they flush green again – like certain acacia trees in the desert. This could be seen as a natural parable. Scientists might explain it as evolutionary adaptation, but a person of faith can see the hand of Allah making the life cycle itself a teaching tool. As the Quran notes, “there is a sign in that for those who reflect.”

Scientific Reflection as Worship: Many Muslim thinkers today encourage exploring these scientific details as a form of appreciating Allah’s workmanship. When we learn, for example, about the process of imbibition in seeds – how water activates enzymes that were inactive – we can parallel that to how Allah’s commands activate what is dormant. When we observe how a tiny seed contains all the information (in its DNA) to become a complex plant when conditions are right, it’s not a stretch to believe that the “information” (or soul, or blueprint) of a human is preserved with Allah, ready to be enacted in a new creation at Resurrection. Thus, science doesn’t detract from the Quranic message; it can amplify our awe. The 9th century scholar Al-Jahiz once marveled at how even the instinct of a chick pecking its way out of the egg is given by Allah – today a biologist might frame it in genetics, but to a believer, knowing the mechanism only deepens admiration for the divine Originator.

In a tangible sense, scientific insights reinforce Quranic themes of divine order and sustenance. We learn that not only does rain bring life, but it does so through a highly ordered set of laws of physics and biology that if tweaked slightly, could fail. This fine-tuning points to wisdom (hikmah). Our study of ecology reveals how everything is interdependent – water, soil, plants, animals – much like the Quran indicates that all creation is by design (“He has set measure for everything”). And every discovery in botany or hydrology can become, for a person of faith, another occasion to say SubhanAllah (Glory be to God). Where an unbelieving scientist sees a marvelous natural process, a believer sees an Ayah in the truest sense: a signpost to the Creator’s majesty.

To conclude this section, modern science has in many ways caught up to the wisdom encapsulated in the Quran’s ancient verses. We now understand better the chain of causes Allah put in place to make rain and greenery possible, and this understanding can make our faith more profound. The metaphor of reviving the dead earth stands strong: every dormant seed that awakens is a mini-resurrection. The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) reportedly said, “The similarity of how Allah will bring the dead to life is like the similarity of a land which is dead, then Allah brings it to life by rain.” Today, watching time-lapse videos of seeds sprouting or satellite images of greening regions provides a visual affirmation of this analogy. Science thus becomes not an adversary but an ally to belief, when approached with the consciousness that these natural laws are signs of Allah’s wisdom. In Islam, there is no fundamental dichotomy between appreciating the how and the why – understanding the how (science) can be an act of worship if it leads one to glorify the Maker and to care for His creation with the trust (amanah) we’ve been given.

Conclusion

The Quran’s verses on rain and the revival of the earth form a beautiful convergence of spiritual teaching and reflective observation. They encourage us to look at something as simple as raindrops on soil and see, not just a natural event, but a message about life, death, and rebirth; about our dependence on Allah and His compassion toward us; about the fleeting nature of worldly adornments; and about the hope of renewal materially and spiritually. We have seen how classical scholars unpacked these verses to affirm core tenets like Resurrection and divine mercy, and how modern insights – both scholarly and scientific – continue to find relevance and inspiration in them.

By pondering the exact Quranic wording and modern scientific findings, we gain a multi-layered appreciation of these signs. On one level, the verses remind us to strengthen our faith in Allah’s power: the One who sends life-giving rain can surely give life to the dead – “indeed, He is over all things competent.”

On another level, they impart a moral worldview: don’t be deluded by life’s greenery when it’s fresh, because it can yellow overnight; instead, strive for the harvest of the Hereafter. They also cultivate gratitude and patience: just as farmers wait for rain and then rejoice, we should be thankful for blessings and patient through dry times, trusting Allah’s timing. And as we have noted, they subtly urge us to soften our hearts – to let the “rain” of the Quran itself penetrate and rejuvenate our spiritual soil, lest we become like barren rock.

In our daily lives, we can integrate this Quranic wisdom in simple yet meaningful ways. For example, developing an environmental conscience becomes almost a form of worship – planting a tree or conserving water isn’t just a good deed socially, but aligning with appreciating Allah’s signs and blessings. When we see news of drought or famine, these verses remind us how dependent all life is on Allah’s provision, instilling empathy and prompting us to prayer (istisqa’, prayer for rain, is a prophetic practice in hard times). When we enjoy a meal of fruits and grains, we can recall the verse that asked “Look at its fruit as it yields and ripens. In that are signs for those who believe.” (6:99) – cultivating shukr (gratitude) as a constant state.

On a spiritual note, whenever one feels one’s heart has become arid – devoid of humility or faith – one can take heart from the metaphor that Allah “can revive the earth after its death.” Hearts are in His hand, and a single shower of guidance could revive a seemingly dead heart. This perspective encourages us never to lose hope in others or ourselves. Just as a landscape can surprise us with flowers after rain, a person’s inner landscape can bloom with the light of iman (faith) after seemingly being lost. Our job is perhaps to prepare the ground (like removing weeds or hard stones of bad habits) and to seek the rain (Allah’s mercy through prayer, Quran, good company) – Allah does the rest.

In moments of contemplation, Muslims are encouraged to observe nature and remember Allah. The next time you step outside after a rainfall and inhale the musky fragrance of wet earth or see a dry patch of grass turning green, consider reciting or recalling these very verses. It can turn a routine moment into an act of dhikr (remembrance of God). As the clouds part and the sun shines on a refreshed earth, it’s as if the earth itself is praising Allah by its revival. We too can join that praise by saying “Alhamdulillah” (All praise is to Allah) for the rain, and “SubhanAllah” (Glory be to Allah) for the incredible cycle of life.

In closing, the Quran’s use of greenery after rain as a sign is a profound example of tafakkur (reflection) encouraged by Islam. It bridges the outer world and the inner world, the seen and the unseen. It shows that faith is not meant to be divorced from the reality around us, but rather that every aspect of creation is intertwined with lessons about the Creator. By studying and embracing these signs, we not only affirm our belief in Allah’s existence and power, but also enrich our understanding of how to live morally (with humility, gratitude, and awareness of the hereafter) and how to steward the earth responsibly.

Ultimately, these verses teach us to see with two eyes: one eye on the material causes (the rain, the seeds, the sunlight) and one eye on the divine cause behind them. With that dual vision, a believer walks the earth neither blinded by nature’s beauty nor oblivious to it, but enlightened by it. As the Qur’an so eloquently puts it: “Indeed, in the creation of the heavens and earth, and the alternation of night and day, and the rain which Allah sends down from the sky – giving life thereby to the earth after its death… are signs for those who use their intellect.” (45:5). May we be among those who observe, understand, and believe – and may our hearts ever revive with the remembrance of Allah, just as the earth revives with the rain.

Leave a comment