Epigraph

Everything in the heavens and earth glorifies God––He is the Almighty, the Wise. Control of the heavens and earth belongs to Him; He gives life and death; He has power over all things. He is the First and the Last;a the Outer and the Inner; He has knowledge of all things. It was He who created the heavens and earth in six Days and then established Himself on the throne. He knows what enters the earth and what comes out of it; what descends from the sky and what ascends to it. He is with you wherever you are; He sees all that you do; control of the heavens and earth belongs to Him. Everything is brought back to God. He makes night merge into day and day into night. He knows what is in every heart. (Al Quran 57:1-6)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

The devout believers in Abrahamic faiths believe that God hears their prayers and if they are well versed in biology and know that common ancestry of all life forms on planet earth cannot be denied without exposing their ignorance, they believe in guided evolution that God influenced evolution according to His plan to achieve the planned results that led to Homo sapiens. They also believe that God can reveal to them through true dreams and indeed blessed saints and prophets with more profound revelations. If all this be true, how does God influence the universe? At the macroscopic level the Newtonian physics applies and it has always been considered to be complete and deterministic. At this macroscopic level the universe seems to be a closed system.

But, do not forget that in 1920s we had a revolution in physics and quantum mechanics came to be and to deny its nondeterminism, Einstein said that “God does not play dice,” and later to deny quantum entanglement he labeled it as, “spooky action at a distance,” but time has proven him wrong on both counts.

Is quantum mechanics the interface where finite meets the Infinite God, a Wise Creator, who has chosen not be a Deist absent Lord, rather a Merciful, Gracious God, who intends to be intimately involved with the beings that He has given the gift of free will?

Introduction to Quantum Mechanics and Theological Inquiry

Quantum mechanics is a branch of physics known for its counterintuitive principles and startling discoveries about nature at the smallest scales. Unlike classical physics—where objects have definite states and deterministic trajectories—quantum physics reveals a world of probabilities, superpositions, and entanglement. Particles can exist in multiple states at once and seem to decide on a particular state only when observed. For example, an electron might behave like a wave spread out in space, yet when we measure it we always find it at a single location. This inherently probabilistic behavior baffled early scientists like Albert Einstein, who famously remarked that “God doesn’t play dice” with the universe. Indeed, quantum mechanics challenges the neat certainty of classical laws, indicating that at a fundamental level, nature has an element of unpredictability and ambiguity.

Such quantum strangeness has opened new conversations about how divine action might be understood in a scientific context. In the classical Newtonian view, the universe was often seen as a clockwork mechanism where the future is strictly determined by the past – a picture that left little room for God to act without suspending or “breaking” the laws of physics. Quantum mechanics, by contrast, introduces genuine uncertainty and openness in physical processes. Instead of a universe where every event is locked in by prior conditions, we have a universe that chooses among possibilities, as if leaving room for subtle influence or guidance. Some theologians and scientists have seized on this idea, suggesting that God could work within the framework of quantum indeterminacy to influence outcomes without violating natural law. In other words, if physical events are not pre-determined but can fall into different outcomes according to probabilities, perhaps God’s will might tip the scales in one direction or another in a way that is undetectable to science yet significant to the course of events. This line of inquiry brings theological perspective into dialogue with quantum physics, asking profound questions: Could quantum mechanics be one of the means by which a transcendent God interacts with the created world? Can the unpredictable behavior of subatomic particles be reconciled with the purposeful agency of the divine? By exploring such questions, we delve into an interdisciplinary adventure at the intersection of modern science and the Abrahamic faith traditions.

In what follows, we will survey key quantum phenomena and examine how each might serve as a window into understanding divine action. We will integrate insights from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, seeing how each tradition’s philosophical perspectives resonate with (or challenge) the quantum picture of reality. Throughout, the goal is to remain scientifically grounded while venturing into metaphysical and theological interpretations. The mystery at the heart of quantum theory – its blurring of the lines between the possible and the actual, the here and the everywhere, the observer and the observed – provides a rich metaphorical landscape for thinking about how an omnipotent and omniscient God could influence the universe. At the same time, we must approach this topic with humility and balance, recognizing both the allure and the limits of drawing connections between quantum mechanics and theology.

Key Quantum Phenomena and Divine Action

Modern quantum physics presents several famous phenomena that challenge our normal intuitions: the sudden collapse of a particle’s wave function upon measurement, the uncanny entanglement of particles across vast distances, the observer effect where the act of observation disturbs a system, and the pervasive indeterminacy or unpredictability in outcomes. Each of these phenomena has sparked not only scientific research but also philosophical reflection. Many have wondered: could these strange features of the quantum world be the channels through which divine will or presence operates within creation? In this section, we explore each quantum concept in turn and consider analogous ideas from theological thought:

Wave Function Collapse and Divine Will

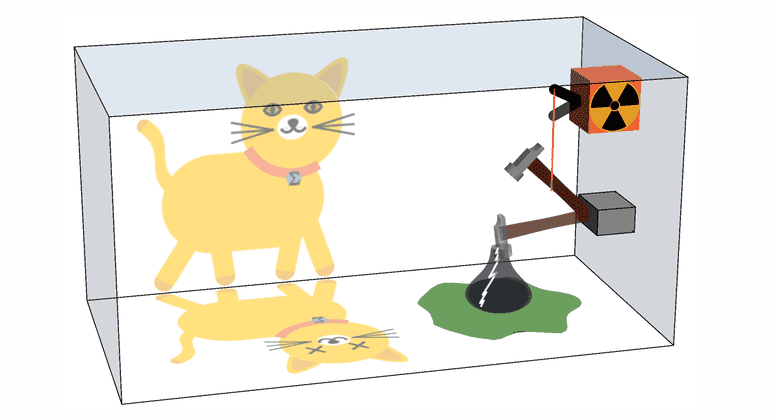

In quantum mechanics, before a measurement is made, a system is described by a wave function representing a mix (superposition) of all possible states. When a measurement or observation occurs, the wave function collapses and the system is found in one definite state (the cat is either definitely alive or definitely dead, in Schrödinger’s famous example). This collapse from multiple potential outcomes to one actual result has invited comparisons to the idea of a choice or decision being made at the fundamental level of nature. Theologically, one might ask: Who or what “chooses” the outcome when a quantum system collapses?

Some thinkers have proposed that divine will could be behind these quantum choices. In this view, God could determine which possibility becomes reality at the moment of wave function collapse, effectively selecting among the quantum options according to a purpose. For instance, if an electron’s spin could end up as either “up” or “down” with equal probability, God’s will might be what decides “up” in a particular instance. Importantly, this would not override the statistical laws of physics. The probabilities predicted by quantum theory would still hold true over many events, but each individual event’s outcome could be guided by God without any observable violation of physical law. This idea has been described as non-interventionist divine action – God acting within the natural probabilities of quantum mechanics, rather than suspending nature’s laws. As one analysis explains, God would not need to “ignore” or break the usual probability distribution; He could choose freely among the possible outcomes in a way that appears random to us but is purposeful from a divine perspective. In this manner, God’s guidance could be exerted “behind the scenes” at the quantum level, with cumulative effects on the larger world (since many microscopic events can influence macroscopic outcomes).

This concept resonates with the religious notion of divine providence – that God oversees and governs the unfolding of events. Wave function collapse presents a natural analogy: just as a myriad of potential paths collapses to a single actual event, one might say God’s will ensures that, out of many conceivable possibilities, the ordained path is realized. It’s a way to imagine God’s sovereignty working in tandem with quantum randomness. Admittedly, this interpretation ventures beyond science into the realm of metaphysics – quantum physics itself does not say a mind is choosing the outcome. Yet it’s a striking image: the quantum world as an open-ended canvas on which divine will “paints” reality moment by moment.

Quantum Entanglement and Omnipresence

One of the most astonishing aspects of quantum mechanics is entanglement. When particles become entangled, they behave like a unified system such that the state of one instantly influences the state of another, even if they are separated by enormous distances. In technical terms, their properties are correlated in a way that defies classical intuitions of locality. Einstein famously called this “spooky action at a distance,” because measuring one particle seems to immediately affect its entangled partner, as if some invisible thread connects them across space. Experiments have confirmed that entanglement is real: entangled particles coordinate their behaviors faster than any signal could travel between them, suggesting a deep interconnection built into the fabric of reality.

For people of faith, it is hard not to see a parallel between entanglement and the theological concept of an omnipresent God. In Abrahamic traditions, God is understood to be fully present everywhere at once – not spread thin, but wholly accessible in every place and moment. This divine omnipresence means that distance poses no barrier to God’s knowledge or action. Quantum entanglement offers a model (or at least a metaphor) of how an influence can be exerted across any separation instantaneously. Just as two entangled particles are never truly isolated from each other, one might say that all of creation is continually connected to its Creator in a kind of “entangled” relationship beyond physical space and time. Some writers have explicitly drawn this analogy, suggesting that God’s interaction with the world could be thought of in terms of a non-local connection, akin to entanglement, that links every particle and every person to the divine. In this view, God does not need to “travel” to intervene at a distant galaxy or to hear a prayer from across the earth – like an entangled particle, the connection is immediate and always active.

Entanglement also hints at a holistic underlying reality: the universe might be deeply relational, with parts existing in meaningful unity with other parts. This dovetails with theological perspectives that emphasize the unity of creation under one God. In Jewish mysticism and Sufi Islamic thought, for example, the interconnectedness of all things is a recurring theme – an idea that the multiplicity of the world is ultimately rooted in the One. Quantum entanglement provides a striking physical illustration of how separate entities can in some sense be one. While scientific discussions of entanglement don’t invoke God, they do suggest that our classical idea of objects being entirely independent is incomplete. Reality is more networked and relational than we once assumed. For believers, it’s a short leap to say this interconnected reality is sustained by the One who is the source of all being. In sum, entanglement may serve as a scientific analogy for God’s intimate linkage with the universe: just as entangled particles respond to each other across any divide, God could be continuously present with each part of creation, holding all in a single, divine frame of reference beyond the normal limits of space and time. It is a poetic way to visualize omnipresence in light of modern physics – not as a vague spiritual idea, but as something almost technically mirrored in the physical world’s deepest structure.

The Observer Effect and Divine Awareness

Another famous feature of quantum mechanics is the role of the observer. In everyday life, observing something doesn’t usually create or change it – if you look at a tree, it continues being a tree just the same. But in the quantum realm, the act of observation is more intrusive. To detect a subatomic particle, one often has to interact with it (for instance, by bouncing a photon off of it), and this interaction disturbs the particle’s state. Thus, observing a quantum system “forces” it into a definite state and in doing so, alters it. This phenomenon is popularly known as the observer effect. It’s as if nature is actively watching for measurements, and only when a measurement occurs does it “decide” on an outcome. This has led to provocative (and controversial) interpretations that consciousness or an observer’s knowledge might be fundamental in the way reality unfolds. While mainstream science interprets the observer effect in terms of physical measurement interactions (not requiring a conscious human observer), the language of “observation” inevitably invites philosophical questions about the nature of awareness in the cosmos.

For theologians, the observer effect raises an interesting possibility: if God is the ultimate observer, does God’s constant observation of the universe ensure that quantum possibilities are continually realized in an orderly way? An old philosophical anecdote captures a similar idea: Does a tree falling in a forest make a sound if no one is around to hear it? Bishop Berkeley’s idealism answered that God is always present as the universal observer, so nothing ever truly goes unwitnessed. In a quantum twist on this idea, some have mused that God’s omniscient gaze could be what “collapses” the wave functions of the world. The act of divine observation would guarantee a definite reality. In a humorous pair of limericks cited by a commentator, a skeptic wonders if a tree remains when no one’s around to see it, and the reply is that God’s always in the quad watching, “Yours faithfully, God,” ensuring the tree continues to be. In other words, God’s awareness could play the role of the measuring apparatus for the entire universe, maintaining consistency and actuality.

However, this idea comes with challenges. If God observes everything all the time, why do we still observe indeterminacy in quantum experiments? One would think that if an omnipresent divine observer is constantly “measuring” the world, quantum systems would always be in definite states (collapsed) rather than in fragile superpositions. Yet we do see interference patterns and other phenomena that imply superpositions persist until measured by us. This has led some to argue that using God as the solution to the measurement problem “proves too much” – it would wipe out the very quantum effects we set out to explain. Perhaps, one might speculate, God chooses to allow the physical world to operate according to quantum principles unless a conscious creature is doing the observing, essentially letting creation run on its own quantum rules except when interacting with conscious minds. Another explanation could be that God’s mode of observation is utterly unlike a physical measurement and doesn’t trigger collapse in the way our instruments do. Theologically, one could say God knows the outcome of every quantum event in advance (or beyond time), so God doesn’t need to perform an observation in the sense of “finding something out” – thus, divine knowledge doesn’t interfere with the natural quantum process.

In any case, the correspondence between the observer effect and God’s knowledge is evocative. It reinforces the idea that knowledge and reality are strangely intertwined. In scripture, it is often affirmed that nothing is hidden from God’s sight. Quantum physics adds a scientific dimension to the notion that the act of knowing is powerful. Even if we set aside the strict technicalities (since quantum observers need not be conscious), we find a poetic parallel: just as a quantum event isn’t settled until observed, perhaps the unfolding of our lives isn’t “settled” without the intimate awareness of God. Believers often find comfort in the idea that God “sees” them at every moment – a divine observer who values and responds to each outcome. The quantum observer effect can serve as a modern parable: reality, at its deepest level, is participatory and responsive, not a mere clockwork that ticks on independently. This can be seen as reflecting a universe in which divine awareness is always at work, subtly upholding the distinction between the possible and the actual.

Quantum Indeterminacy and Free Will

One of the earliest philosophical questions raised by quantum mechanics was what its built-in indeterminacy means for the debate over free will and determinism. In classical physics, if we knew all the positions and velocities of particles (and had infinite calculating power), we could predict everything that would ever happen – a view exemplified by Laplace’s hypothetical super-intelligent demon. Such strict determinism troubled many thinkers because it seemed to leave no room for genuine human choice; every decision would ultimately be the result of prior mechanical causes. Quantum mechanics dramatically changed that picture. The laws of quantum physics are probabilistic, not deterministic. Even with complete knowledge of a system, we cannot predict a single event with certainty – we can only assign probabilities to the various outcomes. There is a fundamental uncertainty in nature (famously quantified by Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle) that is not due to ignorance, but seems to be inherent in the way things are.

This physical indeterminacy has often been seen as a potential “opening” for free will. The logic is that if the physical brain has processes that are not pre-determined but can go one way or another, perhaps the conscious mind or soul could influence those processes. At the very least, the “lockstep” chain of cause and effect is broken at the micro-level, which might allow our mental choices to not be completely governed by prior material conditions. From a theological perspective, this aligns with the long-held belief that humans have been granted a degree of freedom by God. The randomness in quantum events can be viewed as analogous to the freedom in human decision-making: in both cases, the future is not wholly fixed by the past. Some Christian philosophers (like Alvin Plantinga) have noted that a quantum-indeterminate world is much more hospitable to the idea of God granting significant freedom to creatures, without God having to constantly override deterministic laws. In a sense, quantum randomness provides a natural mechanism through which free will might operate or through which God might nudge events while still allowing creatures to make genuine choices.

That said, randomness alone is not the same as free will. Critics point out that simply inserting quantum uncertainty doesn’t magically give humans control over their actions; random brain events are not the same as willed actions. Free will implies intentionality and agency, not mere unpredictability. If our decisions were completely random, that would hardly be free or responsible. So theologians and philosophers refine the idea: perhaps the soul or mind can influence certain quantum outcomes in the neurons of the brain, introducing a bias that correlates with our intentions. Alternatively, some propose that God, in granting the soul a non-physical aspect, made the brain just uncertain enough that the soul (or consciousness) can tip the balance without violating physical laws. These ideas remain speculative, on the frontier of science and metaphysics.

Meanwhile, regarding divine foreknowledge, quantum indeterminacy also offers interesting food for thought. If even God has chosen to let parts of the universe be genuinely indeterminate (as a way to grant creation its own freedom), how does God’s omniscience work? One traditional resolution in Christian theology comes from the concept of God’s “middle knowledge” (as in Molinism). This is the idea that God knows not only everything that will happen, but also everything that could happen under any hypothetical circumstance. In that vein, some have suggested that God infallibly knows the outcome of every quantum event without necessarily determining it by force – essentially, God knows all the counterfactuals of quantum outcomes. For example, God knows that if particle A were in situation X, it would decay at time t (even if, left to its natural indeterminate course, there were a 50% chance of decaying at t and 50% at t’). This kind of knowledge would allow God to accomplish providential plans in a world with genuine randomness: He is never surprised by a quantum outcome, and can orchestrate events knowing in advance how any indeterminate process will resolve. In this way, divine omniscience and providence can be reconciled with a nondeterministic universe. God’s sovereignty isn’t undermined by quantum chance, because what looks like chance to us can still be part of a story known and used by God.

In the Abrahamic traditions, God’s foreknowledge has always been a mystery in relation to our free will. Quantum mechanics doesn’t resolve that mystery, but it provides a fresh metaphor and perhaps a model for thinking about it. It tells us that unpredictability is built into creation, which suggests that a scripted, fatalistic determinism is not the whole story of reality. This inspires a view of the cosmos as a kind of unfolding drama with real choices, rather than a pre-recorded tape. Believers may find it uplifting that physics itself hints at an openness in nature: the future is not wholly written by the past, which harmonizes with the idea that God invites creatures to co-create their destiny to some extent. In summary, quantum indeterminacy adds scientific weight to the intuition that freedom is real. It doesn’t prove humans have free will (that question goes beyond physics), but it removes the old deterministic objection against free will. And if one believes in a God who values love and freely given obedience, it’s fitting that the universe at its core is not a deterministic machine but a theater of possibility, where genuine novelty can happen.

Philosophical and Theological Perspectives

The dialogue between quantum mechanics and theology is enriched by the diverse perspectives of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Each of these Abrahamic faiths brings its own historical reflections on God’s interaction with the world, and each can both contribute to and draw lessons from quantum insights. In this section, we look at how these religious traditions might interpret the quantum phenomena we discussed, and how quantum mechanics, in turn, might illuminate traditional doctrines about divine action.

Judaism: Kabbalistic and Philosophical Insights

In Jewish thought, the interplay between divine providence and the natural order has been a subject of contemplation for millennia. Medieval Jewish philosophers like Maimonides wrestled with questions of how God could be all-powerful and all-knowing and yet humans have free will, or how miracles can happen in a world that normally follows natural law. But perhaps the most intriguing resonance with quantum ideas comes from Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition. Kabbalistic teachings, especially those of the Lurianic Kabbalah, introduce concepts like tzimtzum (divine self-contraction) and sefirot (emanations of divine attributes) to explain how an infinite, omnipresent God interacts with a finite world without overwhelming it. Tzimtzum is the idea that God “withdrew” or concealed His infinite light to create a conceptual “space” for the material universe to exist. This doctrine has surprising parallels with some modern scientific ideas. In fact, some writers have noted that Kabbalah’s depiction of a hidden God sustaining reality foreshadowed certain radical concepts in modern physics, “including the quantum-mechanical collapse of the wave function.” As one analysis puts it, the mystical doctrine of tzimtzum “may have foreshadowed some of the most radical concepts in modern physics.”

The notion that God’s act of making space for creation could be analogous to the reduction of quantum possibilities into a single outcome is a thought-provoking comparison. Both involve a transition from the infinite or many potential states into a single concrete reality.

Judaism also has a strong idea of hashgacha pratit, or divine particular providence, which holds that God’s care extends to every detail of the world. Some classical Jewish texts even suggest that every leaf that falls or every raindrop is guided by divine decree. Such views, common in Chassidic teachings, imply a world where what appears as chance is actually under continual divine supervision. Quantum events, from this perspective, would be no exception – the flip of a subatomic spin could be seen as willed by God, not just a 50/50 coin toss of nature. While a scientist might say “the atom decayed by chance,” a devout Jew might add “– because that was the Creator’s will at that moment.” Interestingly, this does not contradict quantum mechanics, because as discussed, an event can lack a physical cause and yet have a metaphysical reason behind it.

Furthermore, the end of the deterministic Newtonian universe was welcomed by some Jewish thinkers as vindicating a worldview more compatible with Torah. One contemporary Rabbi (the late Menachem M. Schneerson, known as the Lubavitcher Rebbe) noted that the Newtonian clockwork view of reality had been at odds with the classic Jewish understanding, which always made room for miracles and free will. The advent of quantum physics, with its weird and less rigid reality, appeared to restore scientific openness to those spiritual concepts. As one Jewish commentator observed: the “old determinist view of reality accepted by Newtonian mechanics was certainly at odds with the classic Jewish worldview.” Now, however, quantum mechanics allows again for a world of “divine providence, miracles and free choice”, a world in which creatures can interact meaningfully with their Creator. This alignment of modern physics with ancient faith is seen by some as deeply providential: what was once a matter of pure belief (that nature is not the whole story and God can guide events) now finds support in the empirical model of the universe. Of course, others caution that one should not oversimplify; quantum theory doesn’t automatically prove Jewish theology, and Jewish theology is not dependent on any scientific theory. But the consonance between the two – the idea that reality’s ultimate fabric might be “open” and responsive to the divine – is a source of fascination and renewed philosophical vigor in Jewish thought.

In summary, Judaism offers conceptual tools and narratives (from the omnipresence and omnipotence of God in Tanakh, to philosophical ideas of continuous creation, to mystical models of divine hiddenness) that resonate strongly with quantum phenomena. Whether it’s the paradox of Schrödinger’s cat and the paradoxes in the Talmud, or the entanglement of particles and the Jewish sense of spiritual interconnectedness (everyone is responsible for one another), one can find many creative parallels. The key contribution of Judaism here is an emphasis on continuous divine involvement. The world exists because God is constantly saying “Let there be light” in an ongoing act of creation. That poetic notion finds a friendly echo in a quantum universe where outcomes are not fixed until the moment they happen – as if creation is indeed an ongoing process. Judaism encourages us to see the divine not apart from nature, but within it, in the here-and-now sustaining every atom. Quantum physics, in revealing a shadowy sub-reality beneath stable appearances, likewise invites us to wonder if that is where the Shechinah (divine presence) lurks, upholding existence in each quantum jump.

Christianity: Divine Action in a Quantum World

Christianity has a long history of engaging with the science of the day, from the Scholastics who harmonized with Aristotle’s physics to contemporary theologians engaging with relativity and quantum theory. A central concern in Christian theology is how God interacts with the world – how to understand miracles, providence, and answers to prayer in light of natural laws. In the 20th and 21st centuries, many Christian theologians and scientists (often working together in the science-and-religion field) have turned to quantum mechanics as a promising context for God’s action. The attraction is that quantum physics, as we’ve described, softens the strictures of determinism. It creates a loophole of uncertainty where, potentially, God could act undetectably. The idea is not to reduce God to a mere quantum force, but to propose that God’s modus operandi for subtle governance of nature might be through selecting quantum outcomes (as discussed earlier) or influencing quantum fluctuations in just the right way to accomplish divine purposes. This has been articulated in what is called “non-interventionist objective divine action” (NIODA) by theologian Robert John Russell, among others. The term sounds technical, but it reflects exactly what we’ve noted: God acting objectively in the world (really causing events to happen), but in a non-interventionist manner (not suspending or breaking the regular patterns of physical law). Quantum events, being probabilistic, allow for this kind of action because an “intervention” at that level need not announce itself by violating any natural regularity – it would just look like one of the many random outcomes allowed by quantum physics.

Physicist-theologian John Polkinghorne, a former Cambridge particle physicist who became an Anglican priest, was a pioneering voice in this area. He argued that science presents us not with a clockwork universe, but with one that is “open” at the edges, and that divine providence could operate through those open edges. Not only quantum uncertainty, but also chaos theory (sensitive dependence on initial conditions) and other forms of openness in nature could be vehicles for God’s subtle guidance. Polkinghorne suggested that God does not micromanage in a way that violates physics, but rather gently influences outcomes within the latitude that physics affords. Thus, miracles in the biblical sense (like the Resurrection) are still seen as special cases of God’s action (perhaps unique acts of new creation), but God’s ordinary interaction – guiding history, responding to prayers, sustaining creation – could be continuous and unseen, partly via quantum processes.

Another Christian philosopher, Alvin Plantinga, tackled the false dichotomy that either God never does miracles or miracles require breaking inviolable physical laws. Plantinga pointed out that if quantum theory is correct, the physical “laws” are statistical and permit a range of outcomes. Thus, if God causes a highly unlikely event to occur, it’s not a violation of the law – it’s just selecting one of the permitted outcomes that might have had low probability. From the standpoint of physics, such an event is not impossible; it’s just rare. But from the standpoint of purpose, God could have reason to make that rare event happen at a specific time (for instance, a spontaneous remission of cancer, which involves many molecular events that are statistically improbable, could – a believer might say – be guided by God’s hand ensuring those improbable events occur together). In Plantinga’s words, an event like someone rising from the dead doesn’t violate quantum laws, because those laws don’t determine exact outcomes – they only give a distribution, and something extremely unlikely can still happen. This line of reasoning provides a conceptual framework in which classical miracles and everyday providence alike can be understood in light of modern physics. Rather than overthrowing natural law, God can work through the flexibility built into nature.

Christian theology also brings in the concept of the Incarnation – God entering the physical world in the person of Jesus – which adds a unique dimension to discussions of matter and spirit. Some theologians have mused whether the information-like nature of quantum states could enrich our understanding of how spirit relates to matter. For example, if consciousness (like some interpretations of quantum mechanics suggest) has a role in the behavior of matter, then one could see Christ’s miraculous works as an exercise of a divine consciousness with unique authority over matter (“Who is this, that even the winds and waves obey him?” the apostles asked). Such musings are speculative, but they illustrate the creative ways Christians are exploring quantum analogies.

One notable interdisciplinary project in the late 20th century was the Vatican Observatory/CTNS series on “Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action,” which produced a volume specifically on Quantum Mechanics. Scholars from various denominations contributed to these discussions, indicating a broad Christian interest in the subject. The common theme was that quantum mechanics seems to allow causal gaps or indeterminate zones where God’s action can be “fit in” without contradiction. However, Christian thinkers also caution against a simplistic “God of the gaps” approach (where God is only invoked to explain what science currently cannot). Instead, they propose that it’s about a confluence of truths: if the physical world truly has indeterminism, and if God truly acts with sovereignty, then logically God could be active in those indeterminate processes – and this would be continuously true, not just a patch for currently unexplained phenomena.

Moreover, Christianity’s view of God is not only of a transcendent lawgiver but also an immanent sustainer (in the New Testament, “in Him all things hold together”). Some have poetically likened this sustaining action to the stability that emerges from countless quantum events. Just as atoms are stable only as an average of zillions of quantum interactions, one might say the world’s order is the result of God’s constant sustaining involvement at the minute level. It’s a way of seeing the familiar order (like the sun rising every day) not as contrary to God’s action but as because of God’s faithful action through nature. Quantum mechanics adds detail to that picture – showing that underneath the smooth sunrise is a frenetic quantum dance that God is master of.

In summary, Christianity engages quantum mechanics with an eye toward understanding divine action in a scientifically literate way. It brings to the table a rich conceptual vocabulary: miracle, providence, Incarnation, sacramentality (the idea that material things can convey spiritual grace), and so on. Quantum theory doesn’t override these concepts but provides a new lens to examine them. Many Christian thinkers find that this science deepens the sense of mystery and awe for God’s creation, aligning well with the idea that creation is “fearfully and wonderfully made.” By embracing quantum indeterminacy, Christians are framing a view of God’s action that is both transcendent (God as the ground of being who gives reality its existence) and immanent (God as subtly present in every quantum event that forms the tapestry of the world). This dynamic and sometimes paradoxical view mirrors the paradoxes within quantum physics itself – wave and particle, freedom and law, chance and cause – making the dialogue between the two all the more intriguing.

Islam: Causality, Qadar, and Quantum Possibilities

Islamic theology offers yet another perspective on divine action, one that historically emphasizes God’s absolute sovereignty (omnipotence) and the contingency of the created world. A prominent school of thought in Sunni Islam, represented by theologians like Al-Ghazali and the Ash’ari tradition, advocated for occasionalism – the belief that created things have no inherent power to cause events; rather, God directly causes every occurrence in every moment. In this view, what we call “natural laws” are simply the habitual patterns of how God usually orders phenomena, and He is free to depart from these patterns at any time (which would be experienced as a miracle). The classical Islamic occasionalist view holds that the world is re-created anew at each instant, with atoms and their properties (colors, motions, etc.) being continuously brought into being by God. If fire burns cotton, it is not because of the fire’s independent power, but because God creates the burning when fire and cotton come together. This perspective has an uncanny resonance with a quantum picture of reality. In a sense, quantum events happening each moment – unpredictable, without a determined cause from the prior moment – sound like a physical echo of the idea that God is choosing the state of the world moment by moment. Quantum indeterminacy, which says an outcome cannot be attributed to any prior physical cause with certainty, fits comfortably with the notion that the only true cause is God’s will. As one might put it: from an Islamic occasionalist standpoint, every collapse of a wave function is simply God deciding the outcome, since nothing in creation decides itself.

Historically, not all Islamic thinkers were strict occasionalists. The Mu’tazilite theologians, for example, believed that humans have genuine agency (to preserve moral responsibility) and that God allows created things some degree of causal efficacy. Nevertheless, all agreed that God’s power and knowledge encompass all events, whether directly caused or allowed. A relevant Islamic concept here is qadar (divine decree or destiny). Muslims believe that nothing happens except by God’s will, yet humans are accountable for their choices – a stance that implies a balance between divine control and human free will. Some reconciled this by suggesting that God creates the human acts according to our choices (a theory called “acquisition” or kasb in Ash’ari theology). If we translate this into quantum terms: one might say God creates the outcome of a person’s decision at the quantum level in the brain, corresponding to the choice that the person (by God’s grace) made. The randomness of quantum physics could be viewed in Islam as the mechanism by which God’s specific decrees play out without a detectable mechanical cause.

Modern Muslim thinkers have started to engage with these ideas in light of contemporary science. Some, such as physicist Basil Altaie and others, see quantum physics as an opportunity to revive the understanding of tajdid al-khalq (continuous creation) using scientific language. If the universe is not a causal closed box, then materialism’s argument against God’s governance is weakened. Additionally, the Qur’an speaks of phenomena that one could compare with a multi-world or at least multi-dimensional reality (for instance, references to seven heavens, or different planes of existence, which imaginative writers have likened to parallel worlds conceptually). While it’s a stretch to link those directly to the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics, it shows an Islamic openness to worlds beyond our observable one.

Another interesting parallel is the phenomenon of quantum entanglement with the Islamic concept of tawhid (the unity of God and, by extension, the unity of His creation under His command). Entangled particles behave as one system. Similarly, Islamic theology asserts that the entire cosmos is under one unified sovereignty – nothing is independent of God. Some Sufi metaphysics even posited that all minds and all things are interconnected as reflections of the One. The instantaneous communication in entanglement can be seen as a sign that the universe at its root is a unified whole, which complements the Islamic view of a universe unified by God’s will (often expressed by the phrase “Kun fa-yakun”, “Be, and it is” – implying an immediate execution of divine command throughout creation).

Moreover, in Islamic thought, miracles (mu’jizat) are seen not as violations of natural law, but as occurrences that God has always had the power to do and simply does at a chosen time to support a prophet or serve a divine purpose. For an omnipotent God, making a miraculous event happen is no harder than making a mundane event happen – both are acts of will. In a quantum universe, one might say the difference between a “miraculous” event and an “ordinary” one is just in how statistically surprising it is to us. To God, who authors all events, parting the sea is as effortless as causing the sun to rise. Interestingly, if we imagine God normally lets the world run on the most probable course (so miracles are rare), that aligns with the idea that He usually acts in concord with the patterns He set (the Sunnat Allah, or God’s customary way), but occasionally He decrees an outcome that we find astonishing (a low-probability quantum outcome on a grand scale, we might say).

Islamic scholars today sometimes point out that science’s move away from absolute determinism vindicates Islamic teachings about dependency on God. The famous phrase “Insha’Allah” (if God wills) accompanies any statement about the future in Muslim piety – acknowledging that ultimately, what happens is up to God’s will, not just our effort or prediction. Quantum mechanics, with its intrinsic unpredictability, echoes this sentiment: no matter how advanced our science, there is a level at which we must say “if God wills, this will happen,” because we cannot predict with certainty. In this way, quantum physics can actually foster a mindset of reliance on God rather than on human certainty, bringing a scientific validation (or at least a poignant analogy) to a spiritual truth.

In conclusion, Islamic thought – especially through occasionalism and the doctrine of continuous creation – provides a framework that readily embraces a quantum description of nature. The emphasis on God’s continuous involvement resonates with the idea of continuous quantum fluctuations and interventions at the smallest scales. Rather than seeing quantum indeterminacy as a challenge, Islam sees all indeterminacy as only apparent – behind it is a Determiner. To a believer, saying an event had no observable cause is not to say it had no cause, but that its cause might be the direct will of God. Thus, Islam invites us to view the quantum world as a theater of divine creativity, happening at fantastically high speed, with every flicker of existence carrying the command “Be!” from moment to moment. It is a perspective in which science and faith don’t collide but rather converge on a single point: the profound contingency of the universe on something beyond itself.

Challenges and Criticisms

While the exploration of quantum mechanics in connection with divine action is fascinating and illuminating, it is not without significant challenges and criticisms. Both scientists and theologians raise important cautions about how much we should read into quantum phenomena in terms of God’s activity. Here we address a few of these concerns to maintain a balanced view.

Scientific Skepticism: Many scientists, while appreciating the philosophical implications of quantum theory, are quick to point out that quantum mechanics itself makes no reference to God or purpose. The theory works with mathematical equations and experimental observations, and it does not necessitate any divine agency to function. From a strict scientific perspective, invoking God in quantum processes could be seen as an extraneous addition – not needed to explain the data, and not something that can be tested or falsified. In fact, quantum mechanics provides multiple interpretations (Copenhagen, Many-Worlds, pilot-wave, etc.), some of which (like the Many-Worlds Interpretation) eliminate indeterminacy by suggesting that all outcomes happen in branching universes. If one of those interpretations is correct, the idea of God choosing one outcome over another becomes more complex or even moot. Moreover, even within the standard interpretation, saying “God collapses the wave function” is not a scientific explanation; it’s a metaphysical overlay on the process. Scientists might also worry that attributing quantum uncertainty to God’s action is akin to earlier epochs where people attributed lightning or disease to direct divine action – a kind of “God of the gaps” approach that plugs God into the holes of current scientific knowledge. Historically, many such gaps have closed with further research, and the divine explanation was pushed out (e.g., we now explain lightning with electromagnetic theory). Could the same happen with quantum collapse or indeterminacy? Perhaps future discoveries (say, hidden variables or a deeper theory) will explain what currently looks probabilistic, and then where would the room for God be? Proponents of the quantum-divine action view respond that their argument is not based on a lack of knowledge (an epistemic gap) but on the way quantum theory describes nature positively as indeterministic. In other words, they’re not invoking God due to ignorance of the mechanism; they’re saying the mechanism has an inherent openness that is fully accepted by physics, and that openness is where one can logically posit divine guidance. This is a subtle distinction, but it’s an important one to avoid a lazy form of god-of-the-gaps. Still, the scientific critique remains: any talk of God’s influence in quantum events goes beyond what physics itself can ascertain. It ventures into metaphysics or theology, which is fine as long as we acknowledge it’s no longer physics.

Philosophical and Theological Concerns: On the theological side, not everyone is comfortable with the idea of God acting in “hidden” ways in quantum events. Some argue it might conflict with the belief in God’s consistent nature – would God really be flipping coins at the micro level, so to speak? Or, if God is determining those outcomes, then are they truly random? It raises questions about how to understand chance: is “chance” just a word we use for ignorance of God’s action? Traditional Christian theology, for example, affirms that divine providence governs all things – “Not a sparrow falls to the ground outside your Father’s care,” as Jesus said – which implies God is intimately involved in even seemingly random occurrences. The quantum proposal is in one sense just reiterating that, but by focusing on the mechanism, it could unintentionally give the impression that God is a kind of technician operating at the quantum level, which might strike some as a reduction of God’s majesty. There’s also the question of miracles: if God only ever acts through quantum probabilities, can miracles that blatantly override normal experience happen? Some theologians, like Nancey Murphy, caution against defining miracles as “violations” of natural law, preferring to see them as uncommon events that science might not predict but that don’t necessarily break any true law. If the laws of nature are probabilistic, then miracles could be those extremely low-probability events that God brings about for a purpose – which again fits the quantum framework. But others worry this might diminish the awe of miracles, making them sound too mechanistic.

Another philosophical challenge is the mind-body or soul-body interaction problem. If one suggests that the mind influences quantum processes in the brain to allow free will (a theory some have called “quantum consciousness”), this raises debates in philosophy of mind about dualism and the efficacy of mental causation. It’s an ongoing area of speculation with no consensus. Some cognitive scientists dismiss it as unnecessary – they seek purely neurobiological accounts of consciousness that don’t need quantum magic. On the flip side, a few physicists like Roger Penrose have speculated that quantum effects might indeed be part of consciousness. But these ideas remain unproven, and tying them to theology adds another layer of complexity.

Interpretative Stretch: A more general concern is that we might be stretching analogies too far. Quantum mechanics is notoriously weird, and it’s tempting to equate its mysteries with spiritual mysteries. But sometimes the equivalences drawn are superficial. For instance, saying “entanglement is like omnipresence” is a metaphorical comparison – entanglement links specific particles, whereas omnipresence refers to God being fully present everywhere. The mechanism (if any) of God’s omnipresence is a mystery beyond physics. We should be careful not to conflate imagery with identity. Similarly, using uncertainty as a metaphor for free will doesn’t resolve the philosophical intricacies of free will. Randomness is not freedom, though it may be a necessary condition for freedom. The point is that these quantum analogies are intriguing and can spur deeper thinking, but they are not iron-clad models. They carry a speculative element that should be acknowledged. It’s possible to appreciate them as heuristic tools – ways of sparking insight – without insisting that, say, “quantum theory proves free will” or “entanglement proves God exists everywhere.” They prove no such thing; they illustrate and enrich our imagination.

Pluralism of Perspectives: Within the faith traditions, not everyone will agree on employing quantum mechanics in theology. Some may see it as an exciting integration, while others may prefer more classical approaches (e.g., Thomistic philosophy might lean towards Aristotelian concepts of act and potency rather than modern physics analogies). There is also the risk of tying theology too closely to a current scientific paradigm – science evolves, and tomorrow’s physics might have a different view of reality. The history of science-religion dialogue has examples of theologians embracing scientific ideas that later changed, forcing reinterpretations. For instance, process theologians in the mid-20th century were very taken with quantum indeterminacy and chaos theory, but if someday a theory of everything returned a form of determinism, their models would face challenges. The takeaway is that any theology engaging science must do so with both enthusiasm and tentativeness, holding its insights with an open hand.

In light of these challenges, many scholars adopt a humble stance: quantum mechanics provides possibilities and analogies for thinking about God’s action, but it doesn’t give definitive answers. Whether one is more scientifically minded or more traditionally religious, it’s important not to oversimplify the narrative. The conversation between quantum physics and theology is less about finding proof of one in the other, and more about an ongoing, enriching dialogue where each can inform the horizons of the other. By recognizing the limits of our knowledge – scientific and theological – we keep the dialogue honest and avoid the twin pitfalls of naive scientism and naive fideism.

Conclusion and Implications

In the words of Sir Charles Darwin, as he quoted Francis Bacon from his book, Advancement of learning, in the later editions of Origin of Species to establish the proper relationship between religion and natural science:

To conclude, therefore, let no man out of weak conceit of sobriety, or an ill-applied moderation, think or maintain, that a man can search too far or be too well-studied in the book of God’s word, or in the book of God’s works; divinity or philosophy; but rather let men endeavor an endless progress or proficiency in both.

The journey through quantum mechanics and theological thought reveals a surprising and beautiful congruence: both the physical world, as unveiled by modern science, and the spiritual understanding of the Abrahamic faiths, as developed over centuries, point to a reality that is deeper and more nuanced than our everyday perceptions. Quantum mechanics has revolutionized how we view the universe – no longer as a passive machine but as a dynamic tapestry of probabilities, connections, and participatory events. In a similar way, theological reflection portrays the cosmos as a creation – something contingent on a Creator, full of purpose and meaning, and open to the ongoing involvement of that Creator. By integrating these perspectives, we gain a richer narrative about the universe and God’s relationship to it.

We have seen how key quantum concepts can serve as springboards for theological insight. The abrupt collapse of quantum possibilities into one actuality invites us to ponder the role of divine will in shaping the course of events, suggesting that what physics calls a random choice might be, at another level, an intentional act of God. The phenomenon of entanglement, wherein distant objects behave as one, provides a vivid analogy for divine omnipresence and unity, illustrating how the created order could be pervaded by an immediate divine connection that transcends physical distance. The observer effect, which highlights the interplay between knowledge and reality, parallels the idea that God’s knowledge of the world is not passive but rather upholds and actualizes reality – as scripture says, God’s Word sustains creation at every moment. And the pervasive indeterminacy in quantum events resonates with the theological concepts of free will and an open future, demonstrating that a non-deterministic universe is not only scientifically credible but theologically fitting for a world where moral choices and responsive relationships with God truly matter.

The implications of this interdisciplinary exploration are significant. For science, it shows that engaging with theology can provide fruitful ways of interpreting the meaning of scientific findings. It reminds scientists that their work, while focused on empirical and mathematical description, occurs within a broader quest for understanding reality – a quest that humans have always pursued through both rational inquiry and spiritual insight. For theology, the integration with quantum physics offers a way to articulate ancient truths in new language, addressing modern people who are often more conversant with scientific concepts than classical philosophical terms. It provides a fresh apologetic angle: rather than science and faith being at odds, the cutting edge of science is in many ways echoing themes that faith has long affirmed (mystery, interconnectedness, contingency, deeper causality). This can inspire a sense of harmony between our understanding of the world and our devotion to God.

Moreover, this dialogue encourages humility and awe. Both the quantum world and the divine nature elude complete comprehension – they stretch our minds and break our neat categories. As Bryce DeWitt said about quantum physics, physicists “have lost their grip on reality;” in theology, one might similarly say that God ultimately surpasses our full grasp (“His ways are higher than our ways”). And yet, instead of despairing at the inscrutability, we can stand in wonder. We find ourselves participants in a reality that is veiled in mystery at its foundations, suggesting that existence is not a trivial accident but something more profound. Whether one views that profundity as impersonal (as a secular scientist might) or as the personal presence of a Creator (as a person of faith would), the conversation itself elevates our appreciation for the depth of the world.

Looking forward, there are many avenues for future research and dialogue. Interdisciplinary scholars could, for instance, explore the ethical and existential implications of a quantum-connected world: does entanglement have anything to say about the concept of a soul or communal consciousness? Can the probabilistic nature of reality inform theological models of petitionary prayer (perhaps prayer could be seen as influencing which potential outcomes come to pass, in cooperation with God)? How might insights from quantum information theory – where information is fundamental – intersect with religious ideas about the divine Logos (Word) as the information sustaining creation? These are speculative questions, but they indicate the fertile ground at the intersection of quantum physics, philosophy, and theology. We are only at the beginning of understanding how these pieces fit together, and interdisciplinary engagement will be key. Already, we see collaborations between scientists, theologians, and philosophers in conferences and publications dedicated to topics like “quantum physics and the nature of God’s action.” This is an exciting frontier where no one discipline has all the answers, but each can contribute pieces to the puzzle.

In conclusion, quantum mechanics, with its astonishing phenomena, does more than expand our scientific knowledge – it expands our metaphorical language and conceptual repertoire for talking about God’s relationship with the universe. It challenges us to move beyond a simplistic, mechanical worldview to one that accommodates wonder, complexity, and purposeful indeterminacy. The Abrahamic faiths, each in their own way, provide profound frameworks for making sense of a world that is at once law-abiding and yet free, predictable in large scale and yet full of surprises in detail. By viewing quantum reality through the lens of faith, we do not diminish the science – we enrich its significance. And by viewing faith in the light of quantum reality, we do not dilute theology – we sharpen its engagement with the truth of the created order.

Ultimately, both science and theology seek truth and understanding. When they engage in respectful dialogue, as we have attempted here, they can correct, refine, and elevate each other. The result is a more unified vision of truth. We end not with a tidy answer to how exactly God influences the universe (for that remains a mystery beyond full human scrutiny), but with a deeper appreciation that such influence is not only conceivable but perhaps woven into the very fabric of the cosmos. The world, seen through quantum mechanics and eyes of faith, is a world alive with possibility and imbued with the presence of the Creator – a universe that is, in a word, sacramental: ordinary in appearance, quantum in structure, and divine in origin.

Sources:

- Southgate, Christopher. God, Humanity and the Cosmos. Quote on the idea of a transcendent world-observer collapsing wave functions counterbalance.orgcounterbalance.org.

- “The Dartmouth Apologia” (Winter 2011). Article on divine action and quantum mechanics, discussing how God might determine quantum events within allowed probabilities newdualism.orgnewdualism.orgnewdualism.org.

- SermonDownload.net – “Does Quantum Entanglement Explain God’s Omnipresence?” Explanation of entanglement and analogy to omnipresence sermondownload.net.

- Patheos, Dave Armstrong – “Quantum Entanglement & the ‘Upholding’ Power of God”. Discussion of entanglement’s mystery and Einstein’s “spooky action” quote patheos.compatheos.com.

- Wikipedia – “Observer effect (physics)”. Notes on measurement disturbing quantum systems and clarifying it’s not about conscious observers en.wikipedia.org.

- Plantinga, Alvin (Biola University Center for Christian Thought). Transcript where he notes quantum laws are probabilistic, not deterministic cct.biola.edu, and that miracles wouldn’t violate these laws cct.biola.edu.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Causation in Arabic and Islamic Thought”. Summary of Ash‘ari occasionalism: God as immediate cause of every change plato.stanford.edu.

- Times of Israel (A. Poltorak) – “Physics of Tzimtzum I: The Quantum Leap”. Suggests Kabbalistic tzimtzum anticipated ideas like wave function collapse blogs.timesofisrael.com.

- Chabad.org (T. Freeman) – “Quantum Reality & Ancient Wisdom”. Remarks on how Newtonian determinism conflicted with Jewish worldview, whereas quantum allows providence and free will chabad.org.

- Russell, Robert John (et al.), Quantum Mechanics: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action. Discussion distinguishing divine action in quantum from “God of the gaps” newdualism.orgnewdualism.org.

Leave a comment