Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

If you want to tackle the issue only from the perspective of the Quran and Hadith, you can do that: Dr. Shabir Ally Acknowledges that It is the Religious Who Get Possessed by Jinn And Offers Good Practical Advice.

If you want to settle the mystery holistically once for all then you will be well served reading the scientific perspective.

Belief in demons (malevolent spirits in many cultures) and jinns (supernatural beings in Islamic tradition) has persisted for millennia. Many people once attributed mental illness, misfortune, and unexplained phenomena to these unseen entities. Today, medical science, psychology, and other fields provide natural explanations for experiences historically labeled as “demonic.” This article examines the evidence from neurology, psychology, sociology, history, and science to show that demons and jinns are cultural myths rather than objective realities. We will see how seizures and hallucinations emerge from brain processes – not possession; how cultural beliefs and biases can foster supernatural interpretations; how ancient societies filled gaps in knowledge with spirits; and why modern physics and biology find no empirical evidence for such beings. Throughout, we compare religious folklore about demons and jinns with the findings of science, in an accessible yet rigorous analysis.

Medical and Neurological Explanations

For much of history, bizarre or uncontrollable behavior was often blamed on demon or jinn possession. With the advent of modern medicine, we now recognize many natural neurological or medical conditions that were once misinterpreted as supernatural. Key examples include:

- Epileptic Seizures: For centuries epilepsy was considered a “sacred” or demonic affliction – evil spirits were thought to cause the convulsions. Ancient Mesopotamians described seizures as the work of a demon and tried exorcisms as treatment. In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates boldly argued that epilepsy (“the Sacred Disease”) was no more divine than other illnesses, pointing to the brain as its origin. This early medical insight was largely ignored, and well into the medieval era seizures still drew fear and stigma as signs of possession. It wasn’t until the 17th–18th centuries that Western physicians like Samuel Tissot and others revived the view of epilepsy as a neurological disorder rather than a demonic curse.

- Schizophrenia and Psychosis: Symptoms such as hearing voices, seeing visions, or having paranoid delusions are common in schizophrenia and certain psychotic disorders. Before psychiatry, these experiences were often attributed to demons speaking or acting through the afflicted person. In fact, visual or auditory hallucinations – e.g. seeing a ghostly figure or hearing malign voices – fit the definition of hallucinations in a medical sense and are strongly correlated with psychotic disorders like schizophrenia. Historically, a person with schizophrenia might be taken to a priest instead of a doctor. Even today, studies find that a significant portion of patients initially interpret their hallucinations as demonic possession due to cultural beliefs. Modern neuroscience, however, shows that such hallucinations stem from dysfunctions in brain perception circuits, not external spirits. For example, one study found that hallucinating patients have difficulty distinguishing internal neural stimuli from real sensory input – the brain effectively tricks itself, a problem of misidentifying one’s own thoughts as an outside voice.

- Sleep Paralysis: This benign sleep phenomenon is now well-understood biologically, yet in folklore it’s often described as a night demon or evil jinn oppressing a person in bed. Sleep paralysis occurs when a person wakes up from REM sleep but remains temporarily unable to move. In this state, people frequently sense a hostile “presence” in the room, feel pressure on their chest, and may see shadowy figures – classic features of so-called “incubus” or “night demon” attacks across cultures. Neurologists explain that during REM sleep, the brain is highly active and the body is paralyzed to prevent acting out dreams. If the brain awakens before the paralysis resolves, the person becomes aware of their immobility and any lingering dream imagery can intrude into waking vision, causing vivid hallucinations. In essence, the mind is partially in a dream state while awake, projecting scary figures or sensations into the bedroom. Many cultures have named this frightening experience (the “Old Hag” in Europe, “kanashibari” in Japan, “jinn” in parts of the Middle East), but science shows it’s due to disrupted sleep cycles rather than any real demon. As Dr. Alicia Roth explains, history and culture shaped the interpretation of these events as “demons,” but in reality “it is a completely benign condition” arising from a REM/wakefulness overlap.

- Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID): Previously known as multiple personality disorder, DID involves a person exhibiting two or more distinct identities or personality states, often as a coping mechanism after severe childhood trauma. Before modern psychology, a person behaving as if “inhabited” by different personas could easily be seen as possessed by spirits. In fact, the symptoms – memory gaps, speaking in different voices, unusual knowledge or accents in one identity – mirror what many assume to be demonic possession. Mental health professionals have noted that DID is frequently mistaken for possession. One psychotherapist recounts a DID patient who believed she had a demon inside her; in therapy, this “demon” turned out to be a dissociated part of her psyche carrying the pain of abuse. The patient had been told by others she was literally demonic, reinforcing her false belief. Cases like this highlight that what might seem like an evil entity is actually a fragment of the person’s own mind, split off by psychological trauma. Recognizing DID for what it is (a treatable mental disorder) is crucial – attempts at exorcism can actually worsen these patients by validating their delusions instead of integrating their identities.

Neurology Confirms Natural Causes: In recent years, neuroscience has directly linked some “possession” episodes to identifiable brain conditions. For example, a 2016 case report of a man claiming demonic possession found an abnormal lesion in his basal ganglia, and during his episodes there was reduced blood flow in his temporal lobe. Temporal lobe epilepsy has long been suggested as one cause of religious visions or trance-like states; indeed, the famous “exorcism” case of Anneliese Michel in the 1970s is now widely believed to have been epilepsy and psychosis, not a literal demon. These neurological findings reinforce that strange behaviors (e.g. convulsions, voices, trance states) have biological explanations. Electrical discharges, neurotransmitter imbalances, or brain lesions can produce intense subjective experiences – from hearing commanding voices to sensing a “presence” – all without any external spirit. In short, medical science has demystified many conditions once attributed to demonic forces, showing they originate in the human brain and body. As one review notes, even though demonic explanations persisted for centuries, epilepsy and other disorders were gradually understood in natural terms once the scientific method took hold. This transition from demonology to neurology stands as one of the triumphs of medicine over superstition.

Psychological and Sociological Factors

While medical conditions explain the proximate cause of many “possession” experiences, psychology and sociology help us understand why people interpret those experiences as demons or jinns in the first place. Human perception and belief are highly susceptible to context. Several key factors make supernatural explanations compelling to many:

- Cultural Conditioning: From childhood, people absorb the beliefs of their culture about the supernatural. If you grow up in a society where everyone accepts that invisible spirits cause illness or misfortune, you are far more likely to interpret any strange event as the work of those spirits. These beliefs become a mental lens. One cross-cultural study noted that ghostly or demonic encounters are “interpreted in different ways across various cultures”, even though the underlying human experience may be universal. In other words, people everywhere might feel like they’ve encountered an unexplained presence, but a Christian might call it a demon, a Muslim might call it a jinn, a Hindu might call it a bhūt (ghost), and a skeptic might call it an illusion – each defaulting to the explanation their culture has primed them with. Anthropologists observing spirit possession rituals around the world have found that the behaviors exhibited often follow scripts that the culture expects, suggesting people learn how to perform a possession according to local tradition (whether consciously or subconsciously). Social reinforcement also plays a role: in communities with strong belief in possession, showing symptoms can bring attention or authority (e.g. an oracle or shaman figure), which may encourage certain individuals to enter trance states that are then interpreted as spirit possession.

- Cognitive Biases and the Brain’s “Agency Detector”: Humans evolved to be very sensitive to other living agents (like people or predators) in our environment – it’s safer to assume that movement in the shadows is a living threat than to dismiss it. This hyper-vigilant awareness is sometimes called the agency detection bias. It means we tend to attribute unexplained sounds, sights, or events to an “agent” even when none is present. For example, hearing a sudden whisper when you’re alone might reflexively feel like a spirit is nearby, when it could just be the wind. Our brains also constantly seek patterns and meanings, even in randomness. Neuroscientists point out that the mind is “always searching for patterns, making signals out of static, and viewing those signals through a distorted personal lens of culture and experience.” If that lens is full of demons and jinns, it’s no wonder that a creaking floorboard at night is perceived as a ghost. This propensity to find intentional agents behind events (termed pareidolia when seeing faces/figures, or apophenia when linking unrelated events) can produce strong convictions of a supernatural presence. Many “haunting” experiences – a feeling of being watched, a fleeting shadow figure – arise from these cognitive tendencies combined with environmental cues. Psychologists note that confirmation bias then kicks in: people remember the times something weird happened after they watched a scary movie about demons, reinforcing their belief, while they ignore the times nothing happened. Over time, a collection of biased memories can harden into unshakeable faith in the supernatural.

- Stress, Suggestion, and Mass Hysteria: Psychological distress and environmental stressors can trigger episodes that mimic the supernatural. In times of high anxiety, people are more likely to have nightmares, irrational thoughts, or psychosomatic symptoms. If the prevailing belief is demonic influence, these psychological disturbances get labeled accordingly. History provides dramatic examples of mass psychogenic illness (mass hysteria) where groups of people simultaneously exhibited bizarre behaviors with no physical cause, often attributed to demons or witchcraft. A classic case is the Salem witch trials of 1692: a group of young girls in Salem Village began convulsing and accusing townsfolk of bewitching them. The community, steeped in Puritan demonology, truly believed the Devil was at work. In hindsight, historians suggest the girls’ symptoms could have been psychogenic or caused by ergot fungus poisoning (which can induce hallucinations). Regardless, the incident shows how social panic fed on itself – the more people believed witches were possessing children, the more new cases of affliction arose. Sociologist Robert Bartholomew notes that “mass hysterias and social panics are barometers of the time and reflect our collective fears.” In medieval Europe, collective fears of the Devil’s influence led to phenomena like the Dancing Plague of 1518, where hundreds danced uncontrollably, possibly due to stress and suggestion. In modern times, there have been outbreaks of “demonic possession” in schools or villages, often in religious communities, which epidemiologists classify as mass psychogenic events. These tend to happen in culturally homogeneous groups under stress, and the symptoms spread by suggestion and mimicry. Essentially, belief can be contagious – if everyone around you insists demons are real and you start feeling odd, you might display the expected “possessed” behavior too (whether intentionally or not). This is a psychological phenomenon, not a demonic one.

- Role of the Exorcist and Suggestion: The practice of exorcism itself can psychologically reinforce the belief in possession. When a person who believes they are possessed meets a priest or healer who also believes it (or at least performs the ritual), it sets up a powerful expectancy effect. The ritual – incantations, holy water, commanding the demon – provides drama and attention, which can lead the person to act out the role of the possessed (screaming, convulsing, responding to the exorcist’s prompts). In some cases, this serves as a catharsis for the individual’s psychological issues; afterwards they may feel relief and interpret it as the demon being expelled. This is essentially a placebo effect or power of suggestion. However, not all outcomes are harmless. There have been tragic instances where assumed possession was actually untreated medical illness and exorcism led to injury or death. A notorious example is the case of Anneliese Michel in the 1970s: a young German woman with temporal lobe epilepsy and psychosis underwent dozens of Catholic exorcisms. She died of malnutrition and exhaustion, and her parents and priests were later convicted of negligent homicide. In hindsight, her seizures and voices could have been managed by medical treatment, but the overpowering belief in demons led to a fatal outcome. This and similar cases underscore that faith in demons without evidence can have real, devastating effects. Even short of such extremes, psychiatrists observe that focusing on demonic explanations often delays proper psychiatric care. One case study of a woman who had undergone repeated exorcisms for her problems found that receiving a possession diagnosis only reinforced her belief in a supernatural cause and discouraged her from seeking medical help. It was only when she finally got psychiatric treatment (for what turned out to be a dissociative disorder with trauma) that she improved. Thus, psychology teaches us that many purported possessions are manifestations of the mind, often shaped by expectancy and social context, and that treating them as medical issues usually leads to better outcomes than treating them as literal demons.

History shows a clear pattern: when natural phenomena or illnesses were not understood, societies turned to supernatural explanations. Demons, spirits, and gods filled in as causes for everything from bad weather to plagues to mental illness. An anthropological view reveals that these beliefs often served a social or psychological purpose, even though they were factually incorrect. Let’s explore how different eras explained the unexplainable, and how scientific progress gradually replaced these explanations with evidence-based understanding:

- Mental Illness as “Supernatural” in Antiquity: In ancient Mesopotamia and other early civilizations, unusual behavior was almost automatically attributed to spirits. Babylonian cuneiform tablets from ~2000 BCE describe epilepsy and note that the person has been seized by a demon, requiring an exorcism ritual. Similarly, ancient Hebrew texts (and later the New Testament) reference Jesus casting out demons, which many scholars interpret as likely cases of epilepsy or mental illness described in the language of the time. Across the ancient world, there was often no distinction between mental and physical afflictions – both could be seen as the result of spiritual forces. Notably, ancient Egyptian and Greco-Roman medicine started to challenge these ideas. The Egyptians documented a case of traumatic brain injury causing seizures, implying a physical cause. Greek physician Hippocrates not only rejected divine causes of epilepsy, but also theorized that hysteria (a catch-all term for emotional disorders) had natural causes. However, these views were overshadowed for centuries by mysticism. In early Islamic culture, the concept of jinn (invisible beings made of “smokeless fire”) was integrated into explanations of disease and insanity – a person acting irrationally might be literally “majnoon” (Arabic: jinn-affected). The Islamic Golden Age physicians did produce advanced medical texts that often favored clinical explanations over jinn, yet belief in jinn possession at the folk level remained strong (as it still does in many communities). Anthropologist I.M. Lewis noted that spirit possession beliefs are widespread in Africa and Asia, often coexisting with herbal medicine and other remedies.

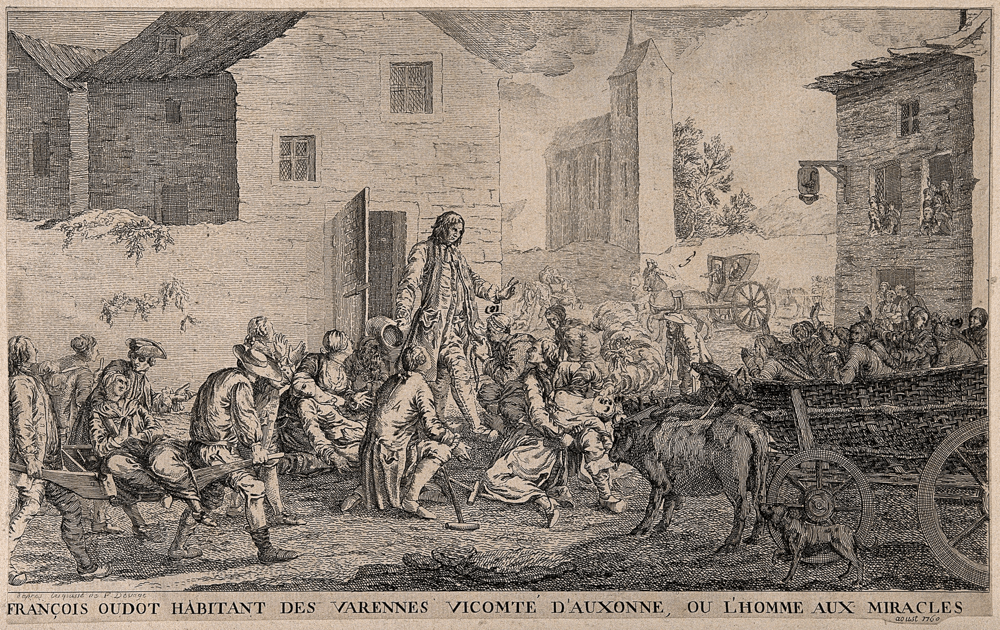

- Medieval and Early Modern Europe: During the Middle Ages in Europe, Christianity dominated worldview, and demonology became a formal study. Behaviors we now recognize as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or even migraines were frequently explained as demonic possession or influence. The Church conducted exorcisms, and witch hunts targeted those (often women) who were thought to consort with demons. Notably, by the late medieval period, some more “natural” theories began to re-emerge. Around the 14th century, learned Europeans started attributing mental illness to imbalanced humors (blood, bile, etc.) rather than just demons. Still, belief in demons causing illness persisted among the populace. Historical records show a gradual narrowing of conditions blamed on possession: one review found that from medieval to modern times, as medical knowledge grew, fewer types of disorders were attributed to demons. For instance, by the 1700s, epilepsy was generally seen as a neurological disorder in medical circles (thanks to figures like Dr. Robert Whytt and others), even if rural communities might still whisper of curses. Exorcism manuals from the 16th–17th centuries reveal an interesting mix of discernment and superstition – some clergy noted that the mentally ill should be cared for, not exorcised, while others doubled down on demonology. A famous case is that of Johann Joseph Gassner, an 18th-century Catholic priest who performed hundreds of exorcisms in Austria–Bavaria; some Enlightenment physicians like Franz Anton Mesmer attended these and concluded that many patients were hypnotized by suggestion rather than actually possessed. The clash between spiritual and scientific explanations was coming to a head.

- Supernatural Phenomena Replaced by Science: As science advanced, one domain after another was pulled out of the supernatural realm into the natural. A few illustrative examples:

- Weather and Astronomy: Thunder and lightning were long thought to be the wrath of gods – Zeus hurling bolts or Thor striking with his hammer. In Indo-European mythologies, the thunderbolt was a symbol of divine power from the sky. Solar eclipses were interpreted as dragons or demons devouring the sun in Chinese, Viking, and Hindu traditions. These interpretations persisted until scientific inquiry provided natural explanations. By the 18th century, Benjamin Franklin demonstrated that lightning is electricity, a natural physical phenomenon, not a weapon of the gods. Similarly, astronomers from Aristarchus to Kepler to Newton showed that eclipses and planetary motions follow predictable laws of physics, not the whims of supernatural beings. These discoveries transformed lightning from a feared omen to a manageable risk (leading to inventions like the lightning rod), and turned eclipses from terrifying omens into tourist attractions.

- Disease and Health: In many cultures, disease was blamed on demonic forces or divine punishment. Medieval Europeans believed the Black Plague was God’s wrath or caused by evil spirits – in some towns, individuals called “plague-spreaders” were even accused of witchcraft. Likewise, illnesses like rabies (which causes agitation and fear of water) were thought to be demonic possession. Over time, the germ theory of disease and advances in medicine eliminated the need for such explanations. For example, epilepsy (once treated by exorcism, as discussed) is now treated with anticonvulsant drugs targeting neural activity. The idea of a “demon” causing fever was replaced by understanding of bacteria and viruses. Even in Islamic tradition, where jinn could be blamed for illness, the great physician Avicenna wrote extensively on natural causes of diseases, laying groundwork for the rejection of supernatural etiologies. By the late 19th century, Pasteur and others conclusively showed microbes cause infection, not evil spirits – a paradigm shift that saved countless lives. Today, exorcism as a cure for illness has virtually vanished from mainstream medicine because science provides far more reliable cures.

- Natural Disasters: Earthquakes, droughts, and other disasters were routinely credited to angry gods or malevolent spirits in pre-scientific cultures. For instance, ancient Japanese lore blamed catfish spirits for earthquakes; Europe in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake saw clergymen preach that it was punishment for sin. However, the development of geology and meteorology offered physical explanations: plate tectonics for quakes, atmospheric pressure systems for storms, etc. One historical turning point was after lightning rods became common – some clergy initially opposed them (arguing that preventing lightning strikes interfered with divine will), but when rods proved effective, the “divine wrath” argument lost credibility. In general, as empirical evidence grew, the space for demons and angry spirits in explaining the world shrank. A telling quote from a historian is, “No one in our ordinary life talks about demons when the language of science explains what we used to call demonic.” We now understand crop failure comes from pests or weather, not a demon blighting the field; and personal misfortune comes from known causes or chance, not a curse.

Anthropologists studying religion and possession observe that these beliefs often served social functions. In societies without scientific knowledge, blaming an unseen spirit could paradoxically be comforting – it offered an explanation (however incorrect) and often a remedy (ritual or prayer) that gave people a sense of control. For example, if a woman in a traditional society began acting erratically (perhaps due to schizophrenia), labeling her as “possessed by a spirit” might actually lead the community to support her via rituals, whereas otherwise they might ostracize or harm her. In this way, spirit possession was a cultural script to handle deviant behavior. As one researcher put it, “the social institution of spirit possession had been preserving the intentionality of socially deviant behaviour” – rather than seeing the person as merely “broken” (a malfunctioning mechanism), the spirit explanation allowed everyone to treat the situation as something meaningful (a battle between good and evil) that could be resolved. However, once scientific understanding is available, these same beliefs persist mostly out of tradition and fear of the unknown. History shows that when a robust natural explanation appears, the supernatural one tends to fade. Lightning is now understood in terms of electric charge, yet the symbol of Zeus’s thunderbolt remains as a cultural memory. Likewise, the idea of demonic possession has drastically retreated over the last century in the face of psychiatry – though it hasn’t disappeared entirely, as we’ll see next.

Physics and Biological Perspectives

Beyond medical and mental health causes, many environmental and biological factors can produce sensations or events that people once attributed to demons, jinns, or ghosts. Modern science has investigated haunted houses, “cursed” places, and ghostly encounters, and often found natural (if sometimes surprising) explanations. Crucially, despite extensive investigation, science has never found concrete evidence of any actual supernatural entities. Here we discuss a few scientific insights that explain why people might experience what they interpret as demons/jinns, and how physics/biology fill in the blanks:

- Infrasound and Electromagnetism – The “Haunted House” Effects: Certain physical stimuli can fool our senses. One famous example is infrasound – sound waves below the range of human hearing (~<20 Hz). Though inaudible, low-frequency vibrations can cause discomfort, anxiety, and even mild hallucinations. Engineers have discovered that a 17–19 Hz sound can vibrate the human eyeball just enough to create optical illusions, making people see hazy figures in peripheral vision. In the 1980s, researcher Vic Tandy investigated a “haunted” laboratory where people felt dread and saw a gray apparition; he traced it to a standing fan emitting a 19 Hz tone that produced those sensations. Once the fan was off, the ghost disappeared – literally a case of vibrations mistaken for spirits. Similarly, strong electromagnetic fields (EMF) near our head can induce odd sensations. Some ghost hunters suspect that old wiring or natural geologic EMFs in “haunted” locations may be influencing the brain’s temporal lobe, which is involved in perception of presence. While research is ongoing, the lesson is that human sensory systems can be fooled by environmental physics. A person might walk into a certain room and suddenly feel cold chills, pressure, and terror – classic signs of a demonic presence – when in fact a barely perceptible infrasound or magnetic field is triggering their brain into panic mode.

- Toxic Substances Causing Hallucinations: Another prosaic explanation for “demonic” experiences comes from chemistry. Poisoning by substances like carbon monoxide (CO), mold spores, or other toxins can induce symptoms eerily similar to a haunting or possession. Chronic CO poisoning (from a faulty furnace, for example) leads to headaches, dizziness, auditory hallucinations (like hearing voices or footsteps), visual hallucinations, a sense of pressure on the chest, and feelings of dread. It’s easy to see why, before modern detectors, a family in a CO-filled house might conclude an evil entity was tormenting them. In fact, many supposed haunted house cases have been solved by finding high CO levels. A recent analysis by a toxicologist noted that carbon monoxide and other poisonings could explain a surge in hauntings and ghost stories during the Victorian era – in those times, coal furnaces, gas lamps, and poor ventilation meant mild poisoning was not uncommon. People literally were being “haunted” by gas leaks. Similarly, certain black molds can cause neurological effects, and consuming ergot-contaminated grain (a fungus) can cause hallucinations (as may have happened in Salem). Before biology was understood, it’s clear how any of these situations would be attributed to malicious spirits. Today, the prudent course is to check the carbon monoxide detector, not call an exorcist, when you sense a “malevolent presence” in your home.

- Pareidolia and Photos: The physics of light and the quirks of our visual system can generate illusions of supernatural figures. Many “ghost photos” or demon sightings have turned out to be tricks of light. Low-light conditions, long exposures, or infrared camera artifacts can create images that appear to show transparent figures or glowing orbs – but these have mundane explanations (dust near the camera flash reflecting light as “orbs,” pareidolia making a smudge look like a face, etc.). Our brains are wired to recognize faces and human-like forms, so even random patterns can look like a demon if we are expecting to see one. This is why ghost hunters often capture what they believe is an apparition in photographs or recordings, yet when examined closely by experts, there is always a physical explanation (lens flare, noise, or even outright hoaxes). No photographic or video evidence of demons or jinns has stood up to rigorous scrutiny – they either show explainable phenomena or cannot be verified. Despite the explosion of cameras and sensors in the modern world, we do not have a single clear, verifiable recording of a supernatural entity, which strongly suggests these things exist only in our perceptions, not in objective reality.

- Lack of Empirical Evidence: Perhaps the most telling scientific perspective is the absence of evidence for demons/jinns when we would expect to find some if they were real. Over the years, researchers and skeptics have tested claims of the paranormal in controlled conditions. Alleged demon-possessed individuals have been evaluated, and invariably a natural diagnosis (like epilepsy or dissociation) is confirmed. Parapsychologists have attempted to detect physical effects of spirits (such as changes in temperature, EMF, etc.) and have come up empty or with inconsistent results. No mysterious “demonic energy” has ever been captured in a lab. As one science writer bluntly put it, “There is no good, verifiable evidence of the existence of an eternal soul or an afterlife of any kind – a prerequisite for the existence of visiting spirits.” If we have no evidence of souls that survive death, it becomes implausible that entities like demons (often considered fallen souls or spirits) exist. Psychologist Steven Novella points out that all the phenomena attributed to demons are subjective, occurring in individual experiences, and never produce objective effects that can be measured independently. They leave no trace – unlike, say, bacteria, which we can culture, or electrical phenomena, which we can detect with instruments. From the standpoint of physics and biology, there is nothing that violates natural laws in a way that would indicate a supernatural being. The conservation of energy, for instance, isn’t broken by objects flying around in exorcisms – because no object truly moves on its own except by trickery or human action. In every well-documented case of supposed paranormal activity, a conventional explanation eventually emerges or the data are too unreliable to conclude anything. The consistent pattern of negative results leads the scientific community to a simple conclusion: extraordinary claims of demons and spiritual entities have not met the burden of proof. Until solid evidence appears (and after centuries, none has), science operates under the null hypothesis that such entities do not exist. This is not a dogmatic dismissal, but an evidence-based position – the same stance we take on fairies, unicorns, or any unfalsifiable concept.

Comparison with Religious and Mythological Views

Different cultures and religions have painted vivid portraits of demons, jinns, and similar supernatural creatures. These beliefs, while culturally important, are products of the human imagination and serve as mythological frameworks for understanding evil or misfortune. Let’s briefly compare some of these traditional views with what science tells us, and see how modernity has challenged age-old beliefs:

- Jinns in Islamic Tradition vs. Science: In Islam, jinn are considered a real creation of God, made of smokeless fire, existing parallel to humans. They are mentioned in the Qur’an and Hadith, and are believed capable of interacting with the physical world and human minds – including “possession” of humans. Many Muslims around the world attribute certain mental illnesses or unexplained events to jinn influence. However, from a scientific perspective, everything attributed to jinns has an alternative explanation. For example, a person “afflicted by jinn” may actually be having a psychotic episode or seizures. In a medical study in the UK, cases of supposed jinn possession were seen only among patients from cultures where that belief is prevalent, highlighting its nature as a culture-bound syndrome. When those patients were treated with psychotherapy or medication, their “jinn” symptoms resolved, further indicating no literal jinn was ever present. Some Islamic scholars even advise seeking medical treatment first, acknowledging that many cases are not true possession. Science would go a step further and say all cases so far can be explained naturally, so invoking a jinn is unnecessary. It’s interesting to note that belief in jinn has declined in regions with higher scientific education, though it remains robust in others. This mirrors how belief in demons has waned in much of the Christian-influenced world.

- Demons in Christianity and Other Cultures: In Christian demonology, demons are typically fallen angels that rebelled against God. They are often blamed for tempting humans into sin or attacking them spiritually. Throughout the medieval period, the Church’s explanation for a wide range of phenomena was demonic activity, and exorcism was an accepted practice. Today, mainstream Christian denominations are more cautious. The Catholic Church, for instance, has very specific criteria and requires ruling out mental illness before performing an exorcism. This itself is an implicit recognition that most cases have natural causes. Only very rarely does the Church declare an event “inexplicable” and proceed with exorcism – and even then, the reported “success” could be due to psychological suggestion. Other religions have their own versions of demons: Hinduism speaks of bhutas and pretas (spirits of the dead who can trouble the living), Buddhism has mara and hungry ghosts, etc. In nearly all cases, these concepts arose in eras when supernaturalism was the default way to explain inner experiences and outer events. Modern scientific progress directly challenges these beliefs. The more we learn about brain chemistry, the less room there is for an external demon to be the source of, say, anger or addiction (which older religions might have personified as a demon of wrath or gluttony). Indeed, surveys show that in many developed countries, belief in literal demons has dropped significantly in the last century. On the other hand, a large percentage of the global population still believes in possession – roughly 40–50% of people in the U.S. profess belief in demonic possession. This indicates that cultural and religious narratives are slow to change, even in the face of scientific evidence. Many find comfort or meaning in these narratives, which science as a dry discipline does not provide. However, holding such beliefs can become harmful if it causes someone to refuse medical care or scapegoat others (e.g. accusing innocent people of witchcraft).

- Mythology as Metaphor: It’s worth noting that in contemporary discourse, even religious individuals often interpret demons and jinns metaphorically rather than literally. For example, someone might say they are wrestling with their “inner demons,” meaning psychological struggles. In literature and art, demons and jinns serve as rich symbols for human vices, fears, and desires. This metaphorical use aligns well with the scientific view: we can talk about “demons” as a poetic way to describe trauma or mental illness, while understanding that no horned creature is actually involved. The danger only comes when metaphor is mistaken for reality. Historically, every time scientific knowledge encroached on what was once thought to be the domain of spirits, it forced religions to adapt. Just as the discovery that mental illness has biochemical roots forces a reinterpretation of demonic possession, so did the discovery of germ theory force a reinterpretation of “demonic contagion,” and so on. Over time, the trend is that science relegates supernatural beings to the margins – either as metaphor, myth, or a matter of “faith” that is compartmentalized away from testable phenomena.

In summary, across cultures demons and jinns have been imagined in various forms – terrifying, capricious beings that explain the random cruelties of life. But as our global knowledge base has grown, these beings have retreated into the shadows of belief. A thunderstorm is no longer seen as a battleground of sky-gods by most people; it’s a low-pressure system. Likewise, a seizure is electrical misfiring in neurons, not an invading devil. Different religions may describe their demons differently, yet none provide evidence that holds up under scientific investigation. Thus, while respecting the cultural significance of these myths, we must conclude that they remain unsubstantiated by evidence and unnecessary for explaining the world around us.

Conclusion

The idea of sinister otherworldly beings – demons, jinns, evil spirits – has captivated human minds for ages. They have populated our stories and our nightmares, offering ready answers for the unknown. However, the march of science and medicine has continually eroded the need for such beings. Neurology explains demonic “possession” as brain dysfunction, not an invading spirit. Psychology shows that our own minds can conjure illusions of demons, especially when primed by culture and fear. History teaches that many phenomena once attributed to devils or jinns are now understood in natural terms. And critically, despite extensive inquiry, no empirical evidence has ever confirmed the existence of supernatural entities. The weight of evidence tells us that demons and jinns are products of human belief, not objective reality.

This is not merely a dry academic point – it has real importance for how we treat those who suffer unexplained experiences. By rejecting the demonic model, we encourage compassionate medical and psychological care for individuals in distress, rather than potentially harmful exorcism or ostracization. It also empowers us to investigate strange occurrences rationally (checking environmental factors like carbon monoxide, for instance) instead of jumping to paranormal conclusions. Embracing a scientific worldview does not cheapen the wonders of the world; rather, it replaces dark superstition with awe at the intricate natural causes behind mental and physical events. As one science communicator quipped, “It’s very likely that ghosts do not exist, but it’s absolutely true that we have ghostly experiences – and the only way that makes sense is if the calls are coming from inside the house.”

In other words, the “demons” we perceive are generated by our brains.

In the end, demons and jinns tell us more about the human imagination and psyche than about the universe. They were our ancestors’ early attempts to grapple with questions of evil, illness, and misfortune. Today, we have better answers to those questions – answers grounded in evidence and reason. While myth and metaphor will always have a place in culture, when it comes to objective claims about reality, we must side with science. And science finds no monsters in the closet. The next time someone fears they are haunted or possessed, we should support them not with ancient rites but with understanding, diagnostics, and treatment. The true wonders of the brain and the natural world are far more fascinating and reassuring than any demon lurking in the dark.

In sum, the overwhelming evidence from the sources covered above converges on one conclusion: the non-existence of demons and jinns as literal supernatural beings. They exist only in our minds and cultures – and that is where we must let them rest.

Additional reading

Birth of Modern Medicine: Jean-Martin Charcot’s Analysis of Shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes

Leave a comment