Epigraph

إِنَّ فِي خَلْقِ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ وَاخْتِلَافِ اللَّيْلِ وَالنَّهَارِ لَآيَاتٍ لِّأُولِي الْأَلْبَابِ

لَّذِينَ يَذْكُرُونَ اللَّهَ قِيَامًا وَقُعُودًا وَعَلَىٰ جُنُوبِهِمْ وَيَتَفَكَّرُونَ فِي خَلْقِ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ رَبَّنَا مَا خَلَقْتَ هَٰذَا بَاطِلًا سُبْحَانَكَ

There truly are signs in the creation of the heavens and earth, and in the alternation of night and day, for those with understanding, who remember God standing, sitting, and lying down, who reflect on the creation of the heavens and earth: ‘Our Lord! You have not created all this without purpose –– You are far above that! (Al Quran 3:190-191)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Robert Lawrence Kuhn is a prominent public intellectual, international corporate strategist, investment banker, and author, known for his expertise in China and his creation and hosting of the public television series “Closer to Truth,” which explores fundamental questions about science, philosophy, and the meaning of existence.

According to him in the above video, as he often pontificates at the end of the episodes, there are only three ways to look at the design in our universe that seems to be fairly obvious to all human observers, but some call it apparent:

- Brute fact or necessity

- Chance

- Design

Presenting these three choices I think he has cleared the smog a lot. The rest should clear, Inshallah: God willing, as I present a series of articles on this theme.

He has made several videos on the theme of argument from design. His tyle is to present 5-6 interviewees in each episode and alternate between for and against. He would generally interview a theist followed by an atheist or an agnostic.

If I were to expand and embellish the theists picked by him and refute the atheists of his choice, I should be able to cover all aspects of the argument and I want to sprinkle this approach with the Quranic verses and insights sometimes as only epigraph and on other occasions expand on them.

So, in this first post in this series focusing on one of the interviewees, William Dembski who is one of the pioneers of Intelligent Design movement.

Firstly, what is wrong with Intelligent Design Movement:

Intelligent Design vs. Methodological Naturalism: A Critical Analysis

Definition of Methodological Naturalism

Methodological naturalism is the guiding principle that scientific inquiry must explain phenomena using only natural causes and processes, without recourse to supernatural intervention. In practice, this means scientists seek explanations that can be observed, tested, replicated, and verified through empirical evidence. This self-imposed limitation has been a core tenet of science since the 17th-century scientific revolution, when appeals to divine authority or miracles were set aside in favor of testability and evidence. Crucially, methodological naturalism is a methodological stance, not necessarily a metaphysical one: it makes no claim that the supernatural does not exist, only that science restricts itself to natural explanations as a matter of process. By doing so, science avoids unresolvable “God-of-the-gaps” dead-ends – where gaps in knowledge are hastily attributed to supernatural causes – and instead presses forward with investigations that yield predictive, falsifiable insights into the natural world. Major scientific bodies emphasize this principle; for example, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences states that science is limited to explanations that can be confirmed by observable and measurable evidence, and that explanations not based on empirical evidence are not part of science. In sum, methodological naturalism undergirds the integrity and progress of science, ensuring that every scientific claim can be scrutinized and tested using natural evidence.

Intelligent Design’s Departure from Methodological Naturalism

The Intelligent Design (ID) movement pointedly departs from methodological naturalism by introducing a supernatural agent as an explanatory cause. ID proponents argue that certain features of the universe and living things are best explained by an intelligent cause (a designer) rather than by unguided natural processes. While they often avoid naming the designer, the implication is a supernatural creator. This violates the basic “ground rule” of science: as one court put it, science by definition requires natural explanations for observed phenomena. In the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover trial (the first legal test of ID in schools), philosophy professor Robert Pennock and biologist Ken Miller explained that science’s methodology cannot accommodate supernatural causes without ceasing to be science. Judge John E. Jones III agreed, noting that ID’s core assertion of an immeasurable designer amounts to an “impermissible supernatural causation” in science. Mainstream scientists overwhelmingly regard ID not as a new scientific theory but as rebranded creationism. They criticize ID for attempting to overturn the rules of science itself rather than working within them. Notably, during the Dover trial, even ID proponents conceded that for ID to be considered science, the definition of science would have to be broadened to allow supernatural forces, a change that would also “embrace astrology” as scienc. In other words, ID’s approach undermines the methodological naturalism boundary that separates science from pseudoscience. By invoking an untestable designer whenever a natural explanation is not immediately obvious, ID creates a science stopper: once a phenomenon is attributed to supernatural design, there is no incentive to investigate further. This abandonment of naturalistic methodology is the chief reason why ID is deemed unscientific by the scientific community.

Scientific Criticism of Intelligent Design

Mainstream scientists have extensively criticized Intelligent Design on scientific grounds, pointing out that its claims conflict with well-established theories in biology, cosmology, and other fields. A hallmark example is ID’s argument from irreducible complexity in biology:

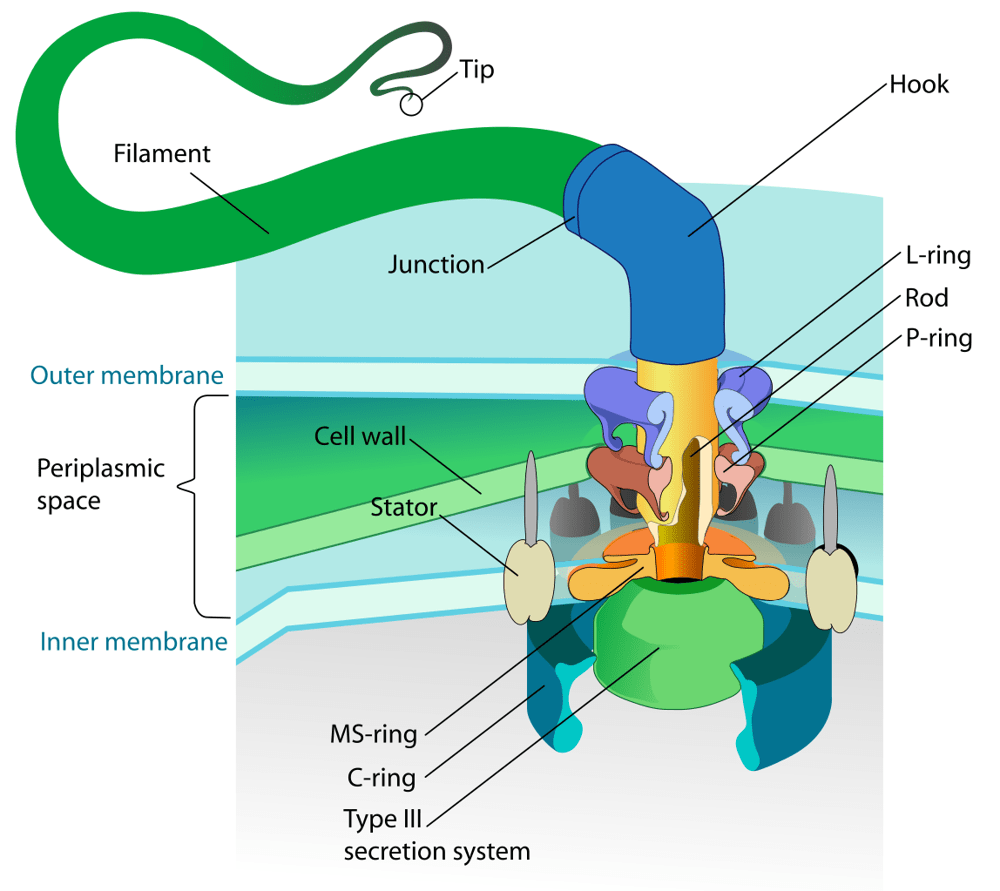

- Biology (Evolution): ID proponents like biochemist Michael Behe claim that certain biological structures (such as the bacterial flagellum, the vertebrate eye, or the blood-clotting cascade) are “irreducibly complex,” meaning they supposedly could not function if any part is removed and therefore could not have evolved step by step. This is essentially a negative argument against evolution, coupled with an assertion that the only alternative is an intelligent designer arranging the parts. However, evolutionary biologists have published numerous rebuttals showing how such systems can evolve through gradual modifications, co-option of parts, and changes of function over time. In fact, during the Dover trial the court examined Behe’s claims and concluded that “Professor Behe’s claim for irreducible complexity has been refuted in peer-reviewed research papers and rejected by the scientific community at large.” For example, structures like the flagellum are now understood to have evolutionary precursors (e.g. the Type-III secretory system in bacteria) that could serve as functional subcomponents on the way to the modern flagellum, rebutting the idea that all parts had to appear at once. In short, ID’s iconic biological examples collapse under scientific scrutiny, and evolutionary theory continues to robustly explain the emergence of complexity.

- Cosmology: In cosmology, ID advocates often gesture to the “fine-tuning” of the universe’s physical constants as evidence of a cosmic designer. It is true that life as we know it would be impossible if fundamental constants (like the strength of gravity or charge of the electron) were even slightly different. But cosmologists do not resort to the supernatural to explain this. Instead, they propose naturalistic frameworks such as the anthropic principle – the idea that we observe these particular constants because only a universe with life-supporting values could produce observers like us – and hypothesize a possible multiverse in which many universes exist with varied constants. These scientific approaches treat fine-tuning as a puzzle to explore with physics and probability, not as proof of divine intervention. Notably, the fine-tuning argument itself isn’t a testable scientific theory; it’s a philosophical inference drawn from science. By contrast, cosmology as a science remains firmly grounded in methodological naturalism, investigating questions like the big bang, cosmic inflation, and particle physics without invoking a supernatural hand. In this way, even in the face of “cosmic design” arguments, scientists prefer hypotheses that can be evaluated empirically, whereas ID leaps straight to an untestable conclusion.

- Other Fields: Similar patterns occur in other scientific domains. For instance, ID proponents question the natural origin of life, arguing that the information in DNA or the complexity of cellular machinery could only come from an intelligent mind. Yet origin-of-life researchers have made progress showing how chemical processes can increase complexity and how natural selection can operate even at the molecular level. While the origin of life is still an open scientific question, proposing a miracle by a designer adds nothing to predictive research—it lacks empirical testability and explanatory detail. Across the board, ID offers “scattered and questionable critiques” of mainstream science without providing a coherent substitute. It fails to generate testable hypotheses or predictions about what we should observe if a designer intervened. For example, ID does not specify when, how, or where an intelligent agent acted in natural history, making it impossible to devise experiments to confirm or falsify its claims. This stands in stark contrast to evolutionary theory, which has successfully predicted discoveries such as transitional fossils and genetic homologies. Tellingly, the ID movement has produced no substantive research program. It has virtually no presence in peer-reviewed scientific literature and has not yielded new data or discoveries. By lacking predictive power, falsifiability, and productivity, ID fails basic criteria of science. In the eyes of critics, it is not a genuine scientific theory but a set of apologetic assertions attempting to cast doubt on evolution. As a result, the scientific consensus rejects intelligent design as pseudoscience.

Comparison with Other Teleological Arguments

The idea that nature shows evidence of purpose or design (teleology) is not new. However, Intelligent Design’s approach differs sharply from other teleological arguments in how it engages with science. To understand why some design arguments are seen as compatible with science (or at least not overtly anti-scientific) while ID is not, it’s useful to contrast ID with two examples: Paley’s classic watchmaker analogy and modern fine-tuning arguments in cosmology.

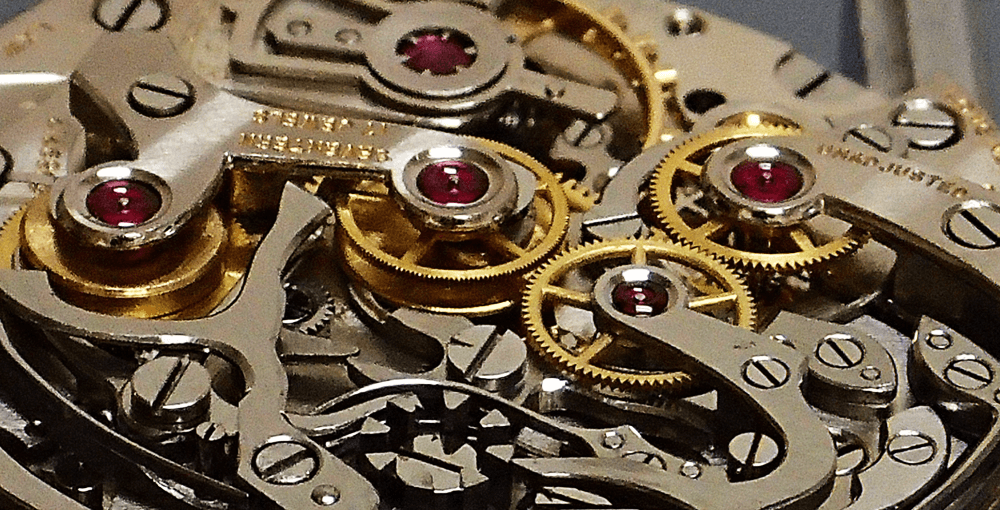

- Paley’s Watchmaker vs. ID: In 1802, theologian William Paley famously argued that if one finds a watch, with its intricate gears working in unison, one reasonably infers a watchmaker. By analogy, the complex adaptation of living organisms implies a divine Designer. This watchmaker analogy was part of Paley’s Natural Theology and essentially a philosophical argument from design. Importantly, Paley presented this argument before the advent of modern evolutionary theory; he lacked a natural mechanism to explain biological complexity, so inferring a designer seemed plausible at the time. Paley’s approach, despite being a religious argument, involved careful observation of nature and largely accepted the scientific knowledge of his day – he was trying to expand understanding by adding a layer of meaning, not contradict the empirical facts available. In practice, Paley’s work “shared more with modern science than with the professional creationists” of today. Now consider Intelligent Design: it arose after Darwin, in a world where evolution by natural selection had provided a robust natural explanation for the complexity Paley marveled at. Rather than incorporating new evidence, ID attempts to turn back the clock. It resurrects Paley’s conclusion (“life is designed”) but ignores the mechanism Darwin and others uncovered. Unlike Paley’s genuine inquiry in an era of ignorance, ID is viewed by critics as a cynical repackaging of discredited ideas “resurrected in a debased form” as part of a culture-war strategy (the ID movement’s own “Wedge Strategy”). Moreover, Paley never claimed his analogy was a scientific theory to be taught in biology class – it was clearly theology/philosophy. ID, by contrast, insists its design inference is science, seeking equal time with evolution. This is a crucial difference: one can appreciate Paley’s argument as a theological interpretation compatible with an acceptance of natural processes (indeed, many theistic evolutionists today see God as the ultimate designer who works through evolution). But ID positions the design argument in opposition to the scientific explanation, urging that supernatural agency replace or override the normal scientific account. In doing so, ID runs afoul of methodological naturalism, whereas Paley’s traditional argument did not violate the scientific method of his time – it merely ventured an explanatory layer beyond it.

- Fine-Tuning Arguments vs. ID: As discussed, the fine-tuned universe argument observes that the constants and initial conditions of the cosmos appear exquisitely balanced to allow life, and infers that an intelligent agent set those parameters on purpose. Like Paley’s, this is a teleological argument, but it operates at the level of cosmic physics rather than biology. Importantly, most proponents of the fine-tuning argument do not claim it as an alternative scientific theory; rather, it’s typically presented as a metaphysical or philosophical explanation for why the laws of nature are as they are. The scientific community can discuss fine-tuning without invoking God: researchers explore natural explanations (e.g. multiple universes or deep principles of physics that necessitate the values we see) and employ the anthropic principle to reason about observer bias. Fine-tuning advocates who favor a designer interpretation generally accept the scientific findings (they don’t dispute the measurements of constants or the astrophysical history of the universe) – they simply argue those findings have deeper intentional significance. This stance does not interfere with the practice of science. A cosmologist can fully engage in research while personally believing that a divine Creator set the laws; that belief does not change how she calculates stellar nucleosynthesis or models cosmic expansion. In contrast, Intelligent Design’s interventionist claims do interfere with science, because ID argues certain natural phenomena (like species origins) cannot be explained by natural law and require direct divine action in their causal history. Fine-tuning arguments may coexist with methodological naturalism (scientists continue investigating natural causes for the universe’s properties, and fine-tuning remains a matter of interpretation). But ID demands violating methodological naturalism within scientific explanations (declaring, for instance, that an intelligent cause must be inserted into biological theory). Another way to put it: teleological arguments like fine-tuning or the watchmaker analogy can be seen as philosophical overlays on top of science – they address the “why” behind scientifically described “how” processes – whereas ID seeks to replace the “how” in science with a miracle. That is why one can often find dialogue between science and religion regarding fine-tuning (it’s a topic at the boundary of science, often discussed in philosophy of physics or theology), but one finds outright conflict when it comes to ID in biology. ID’s approach simply does not meet the standards of scientific methodology, whereas other teleological ideas either operate outside the realm of strict scientific inquiry or alongside it without challenging the naturalistic methods of science.

Legal and Educational Ramifications

Courtroom Verdict: Attempts to introduce Intelligent Design into public school science classes have been struck down in U.S. courts as violations of the separation of church and state. In the landmark case Kitzmiller v. Dover (2005), a U.S. federal court examined whether ID could be taught as science in a public high school. After a six-week trial featuring extensive expert testimony, Judge Jones III issued a 139-page ruling concluding that “Intelligent design is a religious view, not a scientific theory.”

The court found that ID was essentially creationism in disguise, noting that early drafts of the ID textbook Of Pandas and People simply replaced the word “creationism” with “intelligent design” after courts had outlawed teaching creationism. Because the U.S. Constitution’s Establishment Clause forbids the government from endorsing a particular religion, the Dover policy of presenting ID as an alternative to evolution in science class was ruled unconstitutional. Kitzmiller v. Dover built upon precedent set by the Supreme Court in Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), which struck down “creation science” in public schools. In Edwards, the Court held that requiring creationism alongside evolution “attempts to advance a particular religion,” and thus violated the First Amendment. Together, these cases draw a clear line: public school science education must remain secular and scientific, adhering to methodological naturalism.

The legal defeats of ID have had a powerful impact on education. In the wake of the Dover decision, school boards across the United States grew wary of inserting ID into curricula, understanding that doing so could lead to costly lawsuits they would likely lose. No other school district has formally adopted an ID policy since. Instead, some anti-evolution activists shifted tactics to promoting vague “teach the controversy” or “academic freedom” bills (encouraging teachers to critique evolution’s “strengths and weaknesses”), but ID itself has been largely kept out of classrooms by the chilling effect of the Kitzmiller ruling. The Dover trial also had an educational silver lining: it became an opportunity for the public to learn why ID is not considered science. The court’s opinion went into detail about what science is and isn’t, explaining the importance of methodological naturalism and testability in defining science. By affirming that evolution is science and ID is not, the ruling reinforced that topics like evolution must be taught as mainstream science in biology classes, whereas religiously motivated ideas cannot be presented as scientific alternatives.

From a broader perspective, these legal cases underscore the necessity of keeping science education free from sectarian influence. They uphold the principle that students should learn established scientific knowledge and the scientific method in school, without sectarian agendas confusing the picture. Students are of course free to discuss philosophy or religion in appropriate contexts (e.g. social studies or philosophy classes), but when it comes to science class, courts have insisted that methodological naturalism remains the operative framework. This ensures that future generations understand evolution, genetics, geology, and cosmology as the sciences present them – as products of natural processes – while leaving any question of ultimate purpose to personal belief. In summary, the courtroom battles culminating in Kitzmiller v. Dover have decisively determined that Intelligent Design may not masquerade as science in public education. Those decisions have helped safeguard the integrity of science curricula, ensuring that evolution continues to be taught on its scientific merits and that students are not misled into thinking a religious doctrine is a scientific theory. The legal and educational legacy of the ID debate thus reaffirms a fundamental lesson: science and science education thrive when they adhere to methodological naturalism, following evidence wherever it leads and shunning supernatural shortcuts.

Intelligent Design: A Modern Expression of the Argument from Design

Intelligent Design is not science or at least not good science, but that does not prevent it from being a good philosophical argument.

The argument from design (or teleological argument) is a longstanding reasoning for God’s existence that infers an intelligent cause from the apparent order and purpose in nature. Classical philosophers and theologians articulated this idea in different ways. Thomas Aquinas, for example, included a “Fifth Way” in his Summa Theologiae which observes that non-intelligent things in nature consistently act toward beneficial ends. Aquinas concluded that, since these natural objects lack awareness, their goal-directed behavior must be directed by some intelligent being – just as an arrow is directed by an archer. In his words, “things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end… not fortuitously, but designedly… [Therefore] some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.” This highlights the core teleological insight: regularity and purpose in the world point to a guiding intelligence.

A more famous formulation came from William Paley in 1802, using the now-classic watchmaker analogy. Paley invited readers to imagine finding a watch on the ground and considering its origin. The intricate arrangement of gears serving the function of telling time could not reasonably be attributed to mere chance or eternal existence; rather, its functional complexity implies it was contrived by a watchmaker. Paley then argued that likewise “every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature” – only to an immensely greater degree of complexity and perfection. The natural world is filled with parts (like the eye or the joints of animals) that resemble engineered mechanisms serving a purpose. Just as a watch’s purposeful order signifies a craftsman, the complex and adaptive order of living organisms signifies an intelligent Designer of nature. Paley’s analogy powerfully conveyed the intuitive logic that “design implies a designer”, reinforcing the argument that the best explanation for nature’s functional order is a supernatural intelligence.

These classical versions of the design argument share a common core: the observable teleology (goal-oriented structure or order) in the world is best explained by an intelligent cause rather than blind chance. Whether pointing to cosmic order or biological complexity, thinkers like Aquinas and Paley saw the fingerprints of design in nature. Over time, however, such arguments faced serious critiques – most notably David Hume’s contention that the analogy between man-made artifacts and the universe is weak and that one cannot assume the designer has the divine attributes (infinite power, goodness, etc.) simply from the world’s design. Later, Charles Darwin provided a naturalistic explanation for the complexity of organisms (evolution by natural selection), offering an alternative to Paley’s inference of a divine watchmaker. By the late 19th and 20th centuries, the classical argument from design was often deemed weakened or refuted in light of evolutionary theory and philosophical objections. Yet, the intuition that nature’s order signifies mind did not disappear. In fact, it resurfaced in new form at the end of the 20th century with the rise of the Intelligent Design movement.

Intelligent Design as a Contemporary Teleological Argument

Intelligent Design (ID) revives the design argument in a modern context, incorporating contemporary scientific findings into a teleological framework. Emerging in the late 20th century, the ID movement builds on the classical intuition that life and the universe are not products of unguided processes but of purposeful intelligence. Proponents of ID explicitly position it as a successor to traditional design arguments, adapted to “various contemporary scientific developments (primarily in biology, biochemistry, and cosmology).”

In their view, new discoveries have revealed complexities in nature that undirected natural mechanisms (like Darwinian evolution or physical laws alone) allegedly cannot adequately explain, thereby reopening the case for an intelligent cause. While Paley used a watch to illustrate design, ID advocates point to biochemical machines, digital information in DNA, and the precise tuning of cosmic forces, arguing these features go beyond what classical analogies envisioned and demand a guiding mind.

Three core claims characterize Intelligent Design as a modern teleological argument:

- Irreducible Complexity (IC) – Certain biological systems are so complex and interdependent that they could not function with any part missing, and thus could not have evolved through gradual, stepwise adaptations. This idea, popularized by biochemist Michael Behe, asserts that systems like the bacterial flagellum, blood clotting cascade, or cellular “machines” require all their parts to be present simultaneously to work. If no simpler functional precursor could exist, then incremental evolutionary paths fail, and intentional design is posited as the better explanation. (Behe famously analogized an irreducibly complex system to a mousetrap – remove one piece and the mousetrap ceases to function.) ID proponents have identified various micro-level structures – e.g. the rotary motor of a bacterial flagellum – as “molecular machines” exhibiting irreducible complexity that “would have to arise as an integrated unit” rather than by Darwinian accumulation of parts.

- Specified (Complex) Information – The idea (chiefly advanced by mathematician William Dembski and others like Stephen Meyer) that nature contains information-rich patterns that are both highly complex (improbable) and specified (match an independent pattern or function) in a way that undirected processes cannot produce. For instance, the DNA code carries specified information: the precise sequencing of nucleotides in DNA functions like a language or software program that guides life’s operations. ID theorists argue that such information is best explained by an intelligent mind, since “an independently given pattern” found in an exceedingly improbable sequence is a reliable marker of design. Dembski formalized this with an “explanatory filter” logic: if a phenomenon cannot be due to regular law and is astronomically unlikely by chance and conforms to a meaningful pattern, then design is the inferred cause. In simple terms, complex specified information (CSI) in biological systems (like the code in DNA or the intricate coordination of cell processes) signals an intelligent source, just as a meaningful encoded message would.

- Fine-Tuning of the Cosmos – ID advocates often incorporate the fine-tuning argument from cosmology, noting that the fundamental constants and initial conditions of the universe are extraordinarily calibrated to permit life. Science has found that if dozens of physical parameters (such as the strength of gravity, the cosmological constant, or the charge of the electron) were even slightly different, a life-permitting universe could not exist. For example, if the force of the Big Bang’s expansion had varied by one part in 10^60, the universe would have either recollapsed or expanded too fast for stars to form – in either case, life would be impossible. Such examples make the universe appear “fine-tuned” for life, leading to the intuition that mere chance cannot credibly account for this coincidence. ID writers argue that the best explanation for hitting all the “cosmic lottery” numbers necessary for life is that a cosmic Designer set the parameters on purpose. In other words, the universe looks “rigged” in our favor, pointing to intentional calibration rather than random accident.

By emphasizing these points, the Intelligent Design movement presents itself as an updated teleological argument. It consciously moves beyond the simplistic analogies of Paley’s era, instead leveraging contemporary scientific findings as evidence of design. For instance, Paley could marvel at the anatomy of the eye, but ID theorists have electron microscopes and molecular genetics – allowing them to point to the bacterial flagellum’s rotary engine or the digital code in DNA as 21st-century “watches” far more intricate than anything Paley knew. The basic logic is still teleological: these complex, purpose-driven structures and cosmic coincidences are argued to make sense only if nature is the product of mind. ID thus frames itself as a modern form of the design argument, translating classical ideas into the language of microbiology, information theory, and cosmology. It contends that new science has only magnified the impression of design in nature, reinforcing rather than undercutting the case for an intelligent Designer.

It should be noted that ID, as presented by its advocates, is intended not merely as a restatement of theology but as an empirical argument that infers design as the most plausible explanation of certain features of the natural world. In principle, this is framed as a form of abductive reasoning (inference to the best explanation) using scientific observations. While classical teleological arguments were often straightforward analogies or general observations about order, ID proponents attempt to make a more rigorous, evidence-based case that “if certain complex features of life and the universe cannot be adequately explained by undirected causes, then intelligent cause remains as the best explanation.” In this way, Intelligent Design positions itself as a contemporary teleological argument, carrying the design inference into modern scientific debates and claiming to avoid the pitfalls that earlier versions encountered.

Philosophical Justifications for ID’s Design Inference

Beyond the scientific veneer, Intelligent Design offers a philosophical argument grounded in notions of probability, complexity, and information. ID theorists seek to show that inferring an intelligent cause is a rational move when confronted with certain types of phenomena. They draw on concepts from probability theory and information science to formalize what classical proponents treated more intuitively.

1. Probability and “Design Detection”: A key justification for ID’s reasoning is the idea that we routinely infer design in everyday contexts when chance is an implausible explanation. William Dembski emphasizes that in many fields (forensics, archaeology, cryptography, SETI, etc.), investigators distinguish events due to law, chance, or design by considering probabilities. ID applies this logic to nature at large. Dembski’s “explanatory filter” argues that if a natural phenomenon is not mandated by physical law (regularity) and is so statistically unlikely that random chance is not a sufficient explanation, we should consider design. The crucial addition is specification: the unlikely outcome must also match some independent pattern or purpose. For example, a random sequence of 1000 coin flips will always be astronomically improbable, but if those flips specifically encode a meaningful message in Morse code, we rightly suspect an intelligent agent rather than luck. Similarly, ID contends that biological sequences and cosmic constants are not only complex but also specifically suitable for life or function, marking them as products of mind rather than accident. In formal terms, specified complexity (also called complex specified information) is offered as a reliable indicator of intelligent design. This approach attempts to put the inference from design on a more rigorous footing: rather than a vague intuition, it’s a probabilistic argument that the features in question are so unlikely under unguided processes that design becomes the best explanation. Philosophically, this aligns with an inference to the best explanation framework—ID proponents argue that when faced with “very small probabilities” versus “an intelligent cause” as competing explanations, it is rational to choose design as the superior explanation for certain phenomena.

2. Complexity and Irreducibility: ID also justifies its conclusions by analyzing the qualitative nature of complexity in biological systems. Michael Behe’s concept of irreducible complexity is not only a biological claim but also a philosophical point about causal adequacy. If a system cannot function at all unless all parts are present (i.e. it has “several interrelated parts so that removing even one part completely destroys the system’s function”), then gradualist explanations seem causally insufficient, since any precursor would lack a necessary part and thus confer no survival advantage. The argument is that unguided evolution would have no way to “select” or preserve the intermediate stages of such a system, because the intermediate would be non-functional. By process of elimination, if step-by-step natural causes can’t construct it, an intelligent designer is posited as the cause who can purposefully arrange all the parts at once. ID theorists often appeal to our experience of engineered systems: we know certain complex contrivances (like an elaborate machine) require a planning mind to assemble multiple components with a unified purpose. When biology presents us with a microscopic machine (such as the bacterial flagellar motor with its dozens of precisely fitted protein parts), ID argues it’s philosophically justified to extend our reasoning about machines to this natural analog, concluding that a mind engineered it. This is essentially Paley’s logic in a modern key – but bolstered with biochemistry. It also resonates with the intuition noted by thinkers like Thomas Reid that certain kinds of order (“marks of design”) are immediately recognizable as products of intelligence. ID tries to codify those “marks” in terms of irreducible complexity and specified information so that the inference to a designer is not merely subjective but grounded in defined criteria.

3. Information Theory and Analogy to Mind: Another justification comes from viewing biological information through the lens of language and technology. The DNA molecule, with its sequences of nucleotides (A, T, C, G), carries instructions for building proteins, much like a software program carries out functions on a computer. Proponents like Stephen C. Meyer highlight this analogy: “just as the letters in the alphabet of a written language may convey a particular message depending on their sequence, so too do the sequences of nucleotides in the DNA molecule convey precise biochemical instructions” inside the cell. This is a philosophically loaded observation – it invites us to see DNA not as random chemical scrawl, but as encoded information. And as our uniform experience suggests, meaningful information (whether in a book, a computer code, or a message) always comes from an intelligent source. ID argues that it is rational to extend this inference to biological information: if we would never attribute a novel’s text or a functioning computer program to unguided forces, why should we attribute the far more complex genetic code to mere chemistry? By using concepts from information theory (such as the improbability of specified sequences arising by chance, and the lack of a physical law that necessitates the specific sequence), ID proponents claim to ground the design inference in the same reasoning we use to distinguish random gibberish from intentionally arranged information. In effect, the cell is likened to an information-processing system designed by an intelligent agent. This bridges science and philosophy: scientifically we observe the information content in DNA; philosophically we argue that such content is evidence of mind.

Comparing ID’s reasoning with that of classical theistic thinkers reveals both continuity and innovation. Like Paley and earlier design proponents, ID relies on an underlying analogy between natural order and human artifacts, but ID attempts to make that analogy more rigorous. Paley saw “functional complexity” (a term akin to specified complexity) as the hallmark of design in both a watch and an eye. ID simply gives this a probabilistic and information-theoretic framing. In a sense, ID’s arguments are conceptually extensions of Paley’s insight: Paley noted that a watch’s ability to perform a valuable function (timekeeping) due to the precise arrangement of its parts is what indicates design. ID’s notion of specified complexity formalizes exactly that idea – a thing performing a function (specified end) via intricate arrangement (complexity) suggests design. The difference is that Paley’s case was a largely qualitative analogy, whereas ID aspires to be a quantitative argument (with probability bounds and complexity metrics). Meanwhile, Aquinas’s version of the teleological argument was less about complex structure and more about goal-directed behavior in nature; in that respect, ID is actually closer to Paley’s empirical approach than to Aquinas’s metaphysical teleology. What ID adds philosophically is an engagement with modern knowledge: it uses the findings of molecular biology and cosmology as new premises for the old conclusion. It also adds a discussion of method – borrowing tools from probability theory to argue that design inferences can be made in a principled way, not merely as a matter of feeling or analogy. Whether this succeeds is debated, but it represents an effort to update the teleological argument to meet contemporary standards of reasoning, in dialogue with science and analytic philosophy. ID advocates often note that detecting design is a common and reasonable practice (as when we infer archaeologically that tool artifacts were made by humans, or when SETI researchers would infer extraterrestrial intelligence from a patterned radio signal). Thus, they argue, recognizing design in biology or cosmology is philosophically on par with other design inferences, just applied to a larger scale. In summary, ID’s justification is that it is using sound inductive practices and modern concepts to bolster what classical thinkers claimed: that purposeful complexity in nature points to an intelligent cause.

Critiques and Counterarguments

Despite its modern repackaging, Intelligent Design has faced numerous philosophical critiques, many of which mirror the historical objections to the design argument. Critics argue that ID does not, in fact, escape the traditional challenges that beset earlier teleological arguments; in some respects it simply rephrases old difficulties in new terminology. Key critiques and counterarguments include:

- “God of the Gaps” Reasoning: One of the most frequent charges is that ID relies on a gap in current scientific knowledge as evidence of design, an approach often dubbed the “God-of-the-gaps.” Essentially, if science cannot (yet) fully explain some complex feature, ID seizes upon that gap and inserts an intelligent designer as the explanation. For example, Behe argued that because we presently don’t see a stepwise Darwinian path to the flagellum or blood clotting system, design must be the answer. Critics respond that this is an argument from ignorance: our inability to conceive a natural process is not positive proof of an intelligent cause. Historically, many natural phenomena once attributed to direct design (or divine intervention) were later explained by natural processes, so claiming “design by default” risks retreat as science advances. Philosophers also point out that a lack of a known mechanism is a precarious foundation for an inference – it essentially says “we can’t explain this by natural means, therefore it was designed”, which is not logically demonstrative. ID proponents counter that their argument is not mere ignorance but based on what we do know (the specified complexity and tight functional integration), and that known natural mechanisms have known limits. Still, the criticism remains that ID’s structure is largely negative, ruling out evolution or chance and then asserting design as the only alternative. This leaves it vulnerable to any future finding of a natural explanation (which would plug the “gap”) and does not independently confirm a designer’s action beyond the absence of alternatives.

- Not Conceptually New – Parallels to Paley: Another critique is that ID’s concepts of irreducible complexity and specified information are not fundamentally novel, but rather new names for the same features Paley and others already discussed. William Paley noted that a watch’s parts are precisely adapted such that changing any one would ruin its function – essentially describing irreducible coordination. In that sense, Behe’s irreducible complexity is Paley’s argument applied to molecular biology (Paley even anticipated this reasoning by observing that if the watch could reproduce, its complex form would still require a designer). Likewise, the idea of specified complexity – that meaningful improbable order implies design – can be traced to earlier thinkers like Leslie Orgel or even pre-Darwin natural theologians who distinguished between random jumble and organized complexity. ID’s “specified complex information” is often seen as a restatement of the old argument that the informative order in nature (like the complex arrangement of the eye for seeing) bespeaks a mind. Philosophers note that reformulating an argument in technical language doesn’t by itself answer the classic criticisms. Hume’s critique, for example, was that even if we grant design, the cause inferred might be very different from the God of classical theism – it could be a finite or even morally ambivalent designer, or many designers, etc. ID generally leaves the “identity” of the designer open (sometimes saying it could be an extraterrestrial intelligence or a supernatural agent), but that move, meant to sidestep religious questions, also underscores a philosophical weakness: from the inference alone, one cannot conclude omnipotence, omniscience, benevolence, or unity of the designer. In that regard, ID achieves no more than Paley did – it posits a designer, but it doesn’t bridge the gap to the full concept of God without additional theological arguments. Some argue it does even less, since by avoiding naming the designer, it stays silent on the ultimate explanation’s nature, whereas classical design arguments at least intended to support belief in God.

- Existence of Natural Explanations: A direct counterargument to ID’s claims is that the supposed examples of irreducible complexity are not beyond the reach of natural processes. Evolutionary biologists have published detailed rebuttals to Behe, demonstrating plausible stepwise pathways or indirect routes (exaptations) for systems like the flagellum and blood clotting. They point out that “irreducible” systems can sometimes evolve by co-opting parts from other systems or by initially having a different function. For instance, the bacterial flagellum shares components with a simpler secretion system, suggesting an evolutionary precursor that provided a base for the motor to develop. If indeed such natural pathways exist (even if not fully confirmed, the mere feasibility weakens the force of the design inference), then ID’s eliminative argument (“evolution can’t do it”) collapses for those cases. Similarly, the origin of biological information, while not fully understood, is an active field of research (prebiotic chemistry, RNA world scenarios, etc.), and critics say ID prematurely declares it insoluble by natural law. From a philosophical perspective, ID may be committing a false dichotomy: it often frames the explanation as either random chance or intelligent design, ignoring the power of natural selection and self-organization (which are neither pure chance nor conscious design, but natural processes that increase order). Paley’s argument was historically refuted in the eyes of many by Darwin showing a third option (evolution) besides chance and design, and ID is seen as downplaying or dismissing the sufficiency of that third option without convincing justification. Thus, a skeptic would say ID hasn’t truly answered Darwin’s challenge; it has asserted that some things couldn’t evolve, but the scientific rebuttals suggest that ID underestimates nature’s capacity for generating complexity. Insofar as ID’s inference depends on “no known natural cause could produce X,” it remains tentative and subject to revision if a natural cause is found.

- Scientific Legitimacy and Philosophical Value: Philosophers of science also debate whether ID constitutes a scientifically meaningful hypothesis or remains a philosophical/theological claim. The consensus in the scientific community is that Intelligent Design is not supported by empirical research and amounts to pseudoscience or creationism in disguise. While this is a scientific judgment, it carries philosophical implications. One could argue that if ID cannot be formulated in a testable, predictive way, then as an explanation it lacks the robustness that we expect of causal accounts. It might then function only as an argument to the best explanation within a broader metaphysical view (i.e. within a theistic framework, one finds design more plausible, but outside it, one does not). In philosophical discussions, critics like Elliott Sober have contended that design arguments often violate principles of confirmation theory – for example, one needs independent reason to think a designer is likely before using the observations as evidence, otherwise one may be imposing a high prior belief in design on the data. Additionally, the avoidance of specifying the designer can be seen as a strategic philosophical omission: it attempts to make the argument more palatable in a secular context, but it also means ID avoids many hard questions (e.g., who designed the designer? what is the nature of this intelligence? etc.). Classical design arguments, being part of natural theology, readily engaged with the idea that the designer is God (and then faced questions like the problem of evil in design). ID tries to bracket those issues by staying scientifically focused, but philosophers note that a complete argument from design inevitably raises theological questions. If ID sidesteps them, it may leave a truncated argument – one that suggests an intelligent cause but can’t venture any further analysis of that cause. Thus, some philosophers find ID less intellectually satisfying than older design arguments, because it stops short of drawing the full connection to theology, yet also doesn’t provide a new explanatory mechanism (it essentially says “an intelligence did it” without detailing how).

In sum, the counterarguments maintain that Intelligent Design, as a modern argument from design, struggles with many of the same conceptual issues as its predecessors. It has not achieved consensus that irreducible complexity or specified information are qualitatively different from the complexity Paley noted – they may just be more detailed examples. And unless ID can avoid relying on gaps in current science, it remains hostage to future scientific developments. Its supporters see it as a robust inference to the best explanation, while detractors see it as a retreat from the standards of explanatory adequacy and a rebranding of an old inference that was already challenged by philosophers like Hume and scientists like Darwin. The debate, therefore, is not only about biology or physics, but about what counts as a good explanation. ID proponents argue that agency is a perfectly legitimate explanatory category (one we use in everyday reasoning) and that recognizing design in nature is following the evidence. Critics argue that ID has not provided positive evidence of a designer’s activity, only assertions that natural causes fail, making it a philosophically weak argument that doesn’t substantially add to the long history of teleological reasoning.

Conclusion: ID’s Place in the Design Argument Tradition

Intelligent Design undoubtedly functions as a form of the argument from design – it is teleological at its core, reasoning from the perceived purposefulness and complexity in the world to an intelligent cause. As a modern expression of this argument, ID has re-energized discussions about design in both philosophy and public discourse. It has introduced new terminology and drawn attention to intricate scientific details that Paley or Aquinas could never have imagined, thus enriching the conversation with microbiological and cosmological examples. In that sense, ID adds illustrative and methodological richness to the teleological argument: it invites us to consider digital code in cells and the fine-tuning of physical constants, and it attempts a more formal design-detection method using probability and information theory.

However, whether ID adds true philosophical value beyond classical teleological arguments remains contentious. Many analysts conclude that ID’s novelty is more in presentation than in substance. The basic logical structure – order/complexity that is not well explained by chance or physical law implies an intelligent designer – is the same structure the argument from design has always had. ID refines the premise by saying “specified complexity” or “irreducible complexity” are the relevant forms of order, but this is arguably just putting old wine in new wineskins. The strengths and weaknesses of the argument from design therefore largely carry over to ID. On the one hand, the design inference appeals to common sense and the powerful intuition that purposeful arrangements require a purposer; ID capitalizes on this by pointing to very stark examples of apparent contrivance in nature. On the other hand, the inference remains inductive and not deductively certain, and it is only as strong as the exclusion of competing explanations. If one is convinced that natural processes (like evolution or multiverse cosmology) cannot account for the phenomena in question, then ID’s conclusion of a designer will seem compelling. If instead one finds the natural explanations at least reasonably possible, then ID’s leap to a designer will seem premature or unwarranted. In that regard, ID has not silenced the traditional critiques of the design argument; it has merely shifted the battleground to new data.

Philosophically, perhaps ID’s most significant contribution is that it revived interest in teleological reasoning in an era when it was often dismissed. By framing design arguments in the context of contemporary science, ID forced both proponents and critics to grapple again with questions about probability, complexity, and how we infer the unseen from empirical facts. It also highlights a meta-issue: what constitutes a scientific versus a philosophical explanation, and where the boundaries lie. Even if one ultimately agrees with the scientific consensus rejecting ID as biology, one may still ponder the underlying philosophical intuition that the world “feels” designed. The durability of design arguments (from ancient philosophy, through Aquinas and Paley, to modern ID) suggests that they address a basic human inclination to find meaning and purpose in the structures of reality. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy observes, the “perception and appreciation of the incredible intricacy and beauty of things in nature… has certainly inclined many toward thoughts of purpose and design,” and this tendency means design arguments are unlikely to disappear despite critiques. Intelligent Design is a contemporary manifestation of this enduring inclination.

In conclusion, Intelligent Design can be seen as a valid form of the argument from design in that it raises relevant questions about whether chance and necessity are sufficient to account for the world’s order. It carries forward the teleological tradition under the banner of scientific examination. Whether it truly advances that tradition is debatable. Supporters say it strengthens the argument with new evidence and analytical rigor; detractors say it’s essentially the same argument repackaged, adding little beyond a veneer of science. What is clear is that ID has reignited philosophical discussion on teleology: it compels us to ask what the hallmarks of design are and how we should weigh explanations for the phenomena we observe. Even if one ultimately rejects Intelligent Design’s claims, engaging with them can deepen one’s understanding of the classical design argument’s appeal and challenges. In that respect, ID’s resurgence of the argument from design has been philosophically fruitful – it reminds us why the question of design versus accident in the universe is so profound, and why, in one form or another, the teleological argument continues to attract both advocates and critics in the search for understanding our existence. The Intelligent Design movement, standing on the shoulders of Paley and Aquinas, has ensured that the conversation about purpose in nature remains a lively one in modern philosophy of religion.

Leave a reply to Augmenting Javed Ghamidi’s Presentation of Theism to Atheists – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply