Epigraph

When God says, ‘Jesus, son of Mary, did you say to people, “Take me and my mother as two gods alongside God”?’ he will say, ‘May You be exalted! I would never say what I had no right to say –– if I had said such a thing You would have known it: You know all that is within me, though I do not know what is within You, You alone have full knowledge of things unseen –– I told them only what You commanded me to: “Worship God, my Lord and your Lord.” I was a witness over them during my time among them. Ever since You took my soul, You alone have been the watcher over them: You are witness to all things and if You punish them, they are Your servants; if You forgive them, You are the Almighty, the Wise.’ God will say, ‘This is a Day when the truthful will benefit from their truthfulness. They will have Gardens graced with flowing streams, there to remain for ever. God is pleased with them and they with Him: that is the supreme triumph.’ Control of the heavens and earth and everything in them belongs to God: He has power over all things. (Al Quran 5:116-120)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

The Christian claim that Jesus Christ is both a perfect man and fully divine has long been a subject of intense debate. On the surface it presents a paradox: how can one individual simultaneously possess all the limitations of humanity and all the unlimited attributes of divinity? This article analyzes this question from multiple angles. We will examine the philosophical challenges (logical contradictions and metaphysical concerns about essence and identity), consider scientific perspectives (cognitive, physical, and biological constraints), and review comparative theology (how different Christian traditions and historical positions handle the doctrine of Jesus’ dual nature). Throughout, we will see why many argue that being “fully human and fully God” at the same time is problematic, if not impossible, without inviting mystery or contradiction.

The belief that Jesus Christ is both fully divine and fully human is a foundational tenet across many Christian denominations. This doctrine, known as the hypostatic union, asserts that Jesus possesses two distinct natures—divine and human—united in one person. While this belief is widely upheld, various denominations articulate and emphasize it differently.

The Catholic Church firmly upholds the doctrine of the hypostatic union. This belief is encapsulated in the teachings of the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD), which declared that Jesus is “truly God and truly man,” possessing two natures without confusion or division. Catholic theology teaches that Jesus’ divine nature is consubstantial (of the same substance) with the Father, while his human nature is consubstantial with humanity, yet without sin.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity also adheres to the Chalcedonian Definition, emphasizing the mystery of the incarnation. Orthodox theology teaches that Jesus’ two natures are united without confusion, change, division, or separation. This union is viewed as a profound mystery that safeguards the fullness of both his divinity and humanity.

Most Protestant denominations, including Lutherans, Anglicans, and Reformed traditions, accept the Chalcedonian Definition. They affirm that Jesus is both fully God and fully man, a belief reflected in historic confessions and catechisms. For example, the Westminster Confession of Faith states that Jesus, “the Son of God, became man, and so was, and continueth to be, God and man, in two distinct natures, and one person, forever.”

Some Christian traditions, such as the Oriental Orthodox Churches (including the Coptic, Armenian, and Syrian Orthodox Churches), reject the Chalcedonian Definition. Instead, they adhere to miaphysitism, teaching that Jesus has one united nature out of two—divine and human—without mingling, confusion, or alteration. This perspective emphasizes the unity of Jesus’ nature while acknowledging both his divinity and humanity.

Throughout history, various heresies have challenged the doctrine of Jesus’ dual nature. For instance, Arianism denied his full divinity, while Docetism denied his full humanity. The Church addressed these controversies through ecumenical councils, formulating creeds and definitions to clarify orthodox Christology.

The term “non-Chalcedonian churches” typically refers to the Oriental Orthodox Churches, which rejected the Council of Chalcedon’s definitions in 451 AD. As of 2019, these churches collectively have approximately 62 million members worldwide.

The major Oriental Orthodox Churches and their estimated memberships are:

• Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church: Estimates range from 36 million to 51 million adherents within Ethiopia.

• Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria: Approximately 10 million members, primarily in Egypt.

• Armenian Apostolic Church: Around 9 million members globally.

• Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church: Approximately 2.5 million adherents.

• Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch: Roughly 1 million members.

• Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church: Approximately 1 million adherents, mainly in India.

Philosophical Analysis of Both A Perfect Man and Fully Divine

The Law of Non-Contradiction and the Dual Nature Dilemma

At the heart of the issue is a logical problem: the law of non-contradiction states that something cannot be A and not A in the same respect at the same time. Yet the orthodox Chalcedonian Christian claim is that Jesus is both fully God and fully man at once. This seems to violate non-contradiction if “God” entails properties that “man” by definition lacks (infinite vs. finite, creator vs. creature, etc.). Philosophers often formalize the contradiction as follows:

- Premise 1: For any being to be fully God (infinite) and fully man (finite) at the same time is a contradiction.

- Premise 2: The Christian doctrine (Chalcedonian Creed) asserts that Christ is both fully God (infinite) and fully man (finite) at the same time.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the claim that Christ is both fully God and fully man at the same time is a contradiction (analogous to claiming a shape is a square circle).

In other words, saying “Jesus is 100% God and 100% human” can sound like saying “X is 100% A and 100% not-A”, an apparent logical impossibility. For example, God by definition is omnipotent (all-powerful) and omniscient (all-knowing), but a human by nature is neither all-powerful nor all-knowing. How can Jesus have unlimited knowledge and power and at the same time experience limited human knowledge and weakness? If we clearly define “God” and “human,” it seems their essential properties exclude one another as starkly as the properties of a square vs. a circle. One philosopher quipped that applying even a bit of logic to the doctrine “starts to sound like gibberish” when we realize that if Jesus had all divine properties (omniscience, omnipotence, incapability of death, etc.), it clashes with the Gospel portrait of Jesus who “grew in wisdom” and could suffer and die. In fact, the New Testament describes Jesus experiencing ignorance of certain facts (e.g. not knowing the exact hour of the end of days) and undergoing growth in knowledge, which seems incompatible with possessing total omniscience. The logical tension is apparent: “How could Jesus be both omniscient God and non-omniscient human?” as one theologian puts it; “When Jesus was a little zygote in the womb of Mary, did he also know what was happening on some planet at the other end of the universe?”

The same person would have to both know everything and yet not know many things – a direct violation of non-contradiction if knowledge is attributed to the same mind in the same way.

Christian philosophers aware of this challenge often stress that the two natures of Christ are held “without confusion” – meaning Jesus is one person in whom a divine nature and a human nature are united but not mixed. They argue the apparent contradiction can be avoided by specifying that Jesus is not “God and not-God” in the same nature or respect. Instead, he is God in his divine nature and human in his human nature. This distinction is intended to satisfy logic: the divine nature retains divine properties, the human nature retains human properties, and they coexist in one person. However, critics note that even with this caveat, it’s unclear if this truly resolves the contradiction or merely restates it in a more mysterious form. After all, one person (“the same Christ,” as Chalcedon says) is being predicated of two radically different sets of attributes. Leibniz’s law of identity in philosophy holds that if one entity has even one property that another lacks at the same time, they cannot be identical. Applying this: if God (as such) cannot die or be ignorant, but Jesus did die and at times lacked knowledge, then strictly speaking Jesus cannot be identical with God – they would not share all the same properties. Defenders respond that Jesus’ divine nature did not die or become ignorant, only his human nature experienced these things. But since persons, not abstract natures, are the subjects who live, know, and die, the puzzle remains: Did God die on the cross or not? If yes, we’ve asserted the immortal died – a contradiction. If no (only the human nature died), then was it truly God who was incarnate and sacrificed? The identity of the person seems split between two sets of experiences, which starts to resemble two persons more than two natures of one person. This leads to deep questions of personal identity: Can one conscious self have two minds or two centers of consciousness – one omniscient, one limited? If so, in what sense is it a single self? These philosophical quandaries show why many see the dual nature of Christ as a genuine logical paradox.

Essence, Existence, and Metaphysical Tensions (Finite vs. Infinite)

Beyond formal logic, there are metaphysical concerns about how one being could unite both a finite nature and an infinite nature. By definition, God’s essence is infinite, eternal, and necessary (the Source of all existence), whereas a human’s essence is finite, temporal, and contingent (a created being). In classical philosophy (e.g. Aquinas), God’s essence is existence itself and is utterly simple (not composed of parts), while human beings have a composite essence (body and soul, attributes, etc.) and are caused to exist. How then could a single individual encompass both modes of being? Can something be both uncreated and created, both infinite and finite? Such a union of opposites seems to challenge the very notion of what a single “essence” or nature can be.

Christian theology asserts that in Jesus, the divine Son assumed a human nature without ceasing to be divine. But some argue this may compromise the doctrine of divine simplicity and immutability. If God is simple (without parts or change), adding a human nature to the divine person of the Son appears to introduce a new composite state. The Second Person of the Trinity would go from having only the divine nature from eternity to having an additional human nature in time – which is a change. Does this mean God changed? Traditional theology says the divine nature didn’t change; rather, the Son united himself with a human nature. Still, the person of the Son now has two natures, which seems like a composite being (the God-Man) whereas before the Incarnation that person was not composite. This raises a subtle metaphysical issue: if Jesus Christ is one person with two natures, is that one person a single being or a compound of two beings? Normally, one person corresponds to one nature (one “what” per “who”), but in Christ there is one “who” with two “whats.” Some thinkers worry this concept is incoherent unless one of the natures is somehow diminished. Historically, heresies arose when philosophers or theologians tried to resolve this tension by effectively dropping or altering one side of the equation (more on this in Comparative Theology below).

Another angle is the problem of identity over time. If Jesus is God, and God by nature is eternal and immutable, how could Jesus experience processes like growth, learning, or aging? Change and time are features of creaturely existence, not the divine. To say “Jesus is God” and “Jesus is a man” might secretly equivocate on the time or aspect. Perhaps Jesus was God timelessly in his divine aspect, but in time he was man? Yet orthodox doctrine insists at the same time Jesus walked the earth, he was fully God as well. The eternal entered time. To philosophers like Kierkegaard, this was the “Absolute Paradox” – the eternal infinite God in a temporal finite man defies all rational comprehension.

Theological Philosophy: Dual Natures and Divine Identity

In theological terms, the doctrine of the Hypostatic Union (the union of two natures in one hypostasis or person) is meant to safeguard both Jesus’ true divinity and true humanity. The Council of Chalcedon (451 AD) formulated that the two natures are united in one person “without confusion, change, division, or separation”. This carefully balanced statement aims to avoid saying the natures blend into a hybrid (which would be Monophysitism, a heresy) or that they are so apart that Christ becomes two persons (which would be Nestorianism, another heresy). Despite the creed’s careful wording, philosophical questions persist: How can the “properties of each nature be preserved” in one person without that person experiencing an internal contradiction? If Jesus is one person, then when we predicate something of Jesus, we are speaking of that person. Can we say “Jesus knows all things” and also “Jesus does not know some things” and attribute both to the same subject without contradiction? Chalcedon would have us append “…according to his divine nature” for the first statement and “…according to his human nature” for the second. But from a logical point of view, attaching “according to nature X” can seem like special pleading if in reality the same person cannot have mutually exclusive attributes. It raises the question: does Jesus have two minds or two consciousnesses, one corresponding to each nature? Some theologians (e.g. in the “two minds Christology”) have suggested exactly that – Jesus had a divine mind that was omniscient and a human mind that was limited. However, as philosopher Greg Boyd admits, it’s hard to render this coherent; it edges toward seeing Jesus almost as two subjects in one body. If the divine mind is somehow “subconscious” and the human mind is the conscious part, Jesus’ human experience might be genuine, but then is the person fully aware of his divinity? Alternatively, the Kenotic theory (from kenosis, “emptying”) says the Son of God voluntarily emptied himself of some divine attributes (omniscience, omnipotence, omnipresence) in order to become fully human. This makes Jesus’ earthly life more coherent (he truly had limited knowledge, power, presence, etc.), but it means that during the Incarnation, Jesus was not exercising the full divine qualities, raising the question of whether he was still “fully” divine or had temporarily set aside the use of divine prerogatives. Kenotic thinkers argue God can limit himself without ceasing to be God (analogous to an omnipotent being voluntarily not using his power), but more traditional theologians worry this compromises God’s immutability and aseity.

In summary, philosophically one faces a trilemma: affirming both natures leads to apparent contradiction; resolving the contradiction by emphasizing one nature or the other leads to heresy (denying either Christ’s true divinity or true humanity); and appealing to mystery means accepting a proposition that seems to violate basic logical intuition. The logical and metaphysical tension in claiming Jesus is simultaneously finite and infinite, temporal and eternal, omnipotent and vulnerable, is the core of why many say one cannot straightforwardly be a “perfect man and fully God” in the same sense at the same time without breaking the normal rules of identity and non-contradiction.

Scientific Analysis

From a scientific and empirical perspective, the claim of a dual human-divine nature faces additional challenges. While science does not typically evaluate theological doctrines, we can use scientific understanding of human cognition, physical law, and biology to highlight the practical incompatibilities between being fully human and fully divine. Below we examine the issues of mind and knowledge, space and physical limits, and biology and mortality.

Cognitive Science: Human Mental Limitations vs. Divine Omniscience

Human beings have finite brains and minds. Cognitive science and neuroscience inform us about the limits of human memory, learning, and consciousness. A normal human mind must develop from infancy, learn language, accumulate knowledge gradually, and cannot know everything. By contrast, a divine mind (as conceived in monotheistic traditions) would possess omniscience – unlimited knowledge of all facts, all at once. The contrast is stark: an infant human starts with virtually no knowledge and limited cognitive capacity, whereas an omniscient deity knows the position of every particle in the universe and the thoughts of every creature, effortlessly. It seems impossible for one mind to be both of these things. We can illustrate this with the earlier pointed question: Did baby Jesus know about galaxies on the other side of the cosmos while he lay in the manger? If he was fully divine, one might say yes, but that contradicts the observable reality of any baby’s mind. On the other hand, if baby Jesus did not know such things (which is more plausible from a human development standpoint), then was he still omniscient God at that moment? The usual explanation is that Jesus’ divine nature had the knowledge, but his human consciousness did not. However, in scientific terms this suggests a dual consciousness or a partitioned mind. There is no precedent in psychology for a healthy single person having two independent centers of consciousness with such an information gap between them (aside from pathological cases of split-brain patients or dissociative identity disorder, which are impairments rather than a “perfect” state). If Jesus had a normal human brain, that brain’s neural capacity would be insufficient to store and process infinite information. An omniscient mind would presumably overwhelm any finite brain substrate. One would have to propose that Jesus’ divine knowledge resided in a non-physical divine intellect, while his human brain handled day-to-day thinking. But then the human brain would effectively be ignorant of the divine intellect’s contents. Jesus the person might sometimes draw on his divine knowledge (e.g. display supernatural insight) but other times be limited. This is how some explain episodes in the Gospels – e.g., Jesus miraculously knowing someone’s thoughts vs. confessing ignorance about the timing of the end. Still, from a cognitive science view, this is unlike any known human cognitive experience. It makes Jesus’ psychology sui generis (absolutely unique), which places it outside what science can analyze. To put it plainly, divine omniscience does not fit into a human brain. A perfect human mind, even if free of sin, is still a finite mind – it gains knowledge through experience, uses a brain of ~1300 cubic cm, and has to function in one place at a time. The experience of consciousness for an omniscient being (who simultaneously knows every event in the universe) is utterly inconceivable for a human organism. Thus, from the standpoint of cognitive science, being fully human (with a normal human range of cognition) is incompatible with being omniscient. One or the other must be limited: either the divine omniscience is self-limited (as in kenosis, giving up the use of full knowledge), or the human mind is not truly like ours (Docetism would imply Jesus’ “mind” was basically divine wearing a mask of humanity). Both options essentially concede an incompatibility between real human mental life and divine intellect – you cannot have a genuinely human consciousness that is at the same time the all-seeing mind of God without contradiction or a miraculous suspension of how minds work.

Physics and Space: Omnipresence vs. Physical Localization

Classical theology teaches that God is omnipresent – present everywhere in space (and transcending space). A human body, however, is localized to a single place at a time and constrained by physical movement. Jesus of Nazareth, during his life on Earth, occupied a specific region of space (living in Galilee, walking from village to village). The physical laws governing human bodies mean Jesus could not, say, be in Nazareth and Jerusalem simultaneously with his human body. But if he was fully divine, one might expect that as God he is present everywhere in the universe. Was Jesus simultaneously occupying all space even as his human nature was confined to one location? Some theologians say yes – that in his divine nature he continued to fill heaven and earth, even while his human nature was limited. This effectively means that the Person of Jesus had two modes of presence: universal (as God) and local (as man). But can one person have two different locations or extensions in space? This again is hard to imagine. It might be analogous to someone operating an avatar: the divine Person still exists everywhere but is operating within the “avatar” of a human body. If so, is that one person or are we back to two personas? Physically, an infinite omnipresent being concentrating itself in one point goes against what we know about spatial existence. Physics tells us that material bodies cannot bilocate or be infinite in extent. If Jesus at point X on earth is fully human, his body’s presence is only at X. Claiming he is also “fully present” at all other points in the cosmos is a statement no physicist could make sense of – it defies the notion of a localized incarnation.

Related to omnipresence is omnipotence (unlimited power). If Jesus is God, he has the power to uphold the universe itself. Yet as a man, Jesus experienced fatigue, hunger, and physical weakness. The gospels recount him falling while carrying the cross, for example. A human body can only exert so much force and needs rest; it certainly cannot juggle planets or wield infinite energy by itself. Christian doctrine holds that Jesus still had access to divine power (hence the miracles), but notice that even in the Gospels, he isn’t constantly using omnipotence for his own comfort – he still sits, walks, sleeps, and indeed suffers. If his divine nature was always fully activated, one might wonder why he would ever be tired or allow himself to be injured. The reconciliation offered is that Jesus chose not to use his infinite power for self-benefit (and only used it for specific miracles as part of his mission). That may preserve the idea of omnipotence in principle, but effectively it means for most of his life Jesus functioned as a normal human, subject to the same physics as we are. This is indistinguishable from not actually having the infinite power in any manifest way. From a scientific perspective, a being that never uses certain supposed capacities might be functionally equivalent to not having them (during that period).

In summary, physics imposes finitude: a human body occupies a finite volume and can only do finite work. The attribute of filling all space (omnipresence) or exerting infinite force (omnipotence) cannot be realized within a single human organism. If Jesus remained omnipresent and omnipotent as God, then the “Jesus” walking in Palestine was not the totality of his person (part of him would be “elsewhere” doing God things). If he relinquished omni-presence/potence while on earth, then at that time he wasn’t exercising the full divine attributes. Either scenario underscores that fully human life and fully divine ability do not neatly coincide. In physical terms, you cannot fit an infinite presence into a six-foot tall human frame – one has to concede a limitation or a duplicity of presence that is beyond any scientific paradigm.

Biology and Mortality: Human Frailty vs. Divine Immortality

A key difference between humanity and divinity is mortality. Humans (as biological organisms) are subject to death – their bodies can cease to function and decay. God, on the other hand, is typically defined as immortal and eternal, not subject to death or corruption. The Christian story itself hinges on Jesus’ death on the cross and subsequent resurrection. But here is a stark paradox: Can God die? If Jesus is fully God, one would say God died on the cross in 33 AD. Yet many theologians balk at the statement “God died,” because God as an eternal being cannot cease to exist or be extinguished. Usually they clarify that the human nature of Jesus experienced death, not the divine nature. However, death in a human means a separation of the soul from the body and the cessation of bodily life. If we say “Jesus died,” we are saying that person underwent death. If that person is God, we have the puzzle of an immortal being undergoing a mortal experience. As one philosopher pointed out using Leibniz’s law: if at time t0 Jesus died, but at time t0 God (in his divine nature) did not die, then by that time-indexed property Jesus is not identical to God. One entity has the property “died at t0” and the other does not, meaning we are talking about two different subjects unless we allow an “exception” to identity law. Theologically, the church tried to allow this exception by distinguishing nature: the person of the Son died in respect of his humanity. But again, only a fraction of what Jesus is (his human aspect) was subject to death, while another aspect (divine) was immune. It’s hard to call that one being; it sounds like two acting in concert.

From a biological perspective, Jesus’ human body was like ours – it had cells, blood, a beating heart, etc. That body could be injured (he bled), it needed food and water, and ultimately it expired on the cross (the heart stopped, cells stopped metabolism). Divine nature, however, if we think analogically, doesn’t have cells or a heart to stop. An immortal, infinite being has no literal life signs to lose. Thus for Jesus to be fully human, his body had to be truly killable; and indeed it died. To be fully divine, somehow the same Jesus must also be truly unkillable. Reconciling this, as with other points, required saying the body (human nature) died but the divine Logos did not die – instead, perhaps the Logos was temporarily “separated” from the body until the resurrection. If so, then at death the two natures actually came apart (even if only for three days), which Chalcedon says should not happen “without separation.” This shows the internal strain in the concept: being both mortal and immortal is as straightforward a contradiction as one can get. Biologically, either the organism is mortal or it isn’t. There is no natural way for an organism to be partially mortal.

Another biological consideration is human needs and weaknesses. As a man, Jesus got hungry, thirsty, felt pain, and experienced emotions like anguish. God (in classical theology) does not experience hunger or pain; God is typically seen as self-sufficient and even impassible (not overcome by pain or involuntary suffering). Jesus sweating blood in Gethsemane or crying out in agony on the cross does not align with an image of impassible deity. If one says “that was only the human nature feeling pain,” it circles back to a split in experience between the natures. A fully divine Christ would feel no pain and need no sustenance, while a fully human Christ would. So to be both, again one nature’s experiences must be compartmentalized away from the other’s. Scientifically, a being that needs oxygen to survive (like any human) cannot at the same time be a being that has no such dependency (as God would have no biological needs).

In summary, human biology is finite and fragile, while divine life is infinite and invulnerable. The Incarnation claims these two were united, but analyzing it, we find that many attributes of humanity (ability to suffer, die, change) directly conflict with attributes of divinity (impassible, immortal, immutable). From a biological and physical standpoint, one entity cannot simultaneously be both without essentially segmenting the attributes. The incarnation thus either requires accepting a miraculous suspension of normal rules (a mystery beyond science) or acknowledging that Jesus’ experience was effectively one nature at a time – which undermines the claim of “fully both at once.” Science would say a creature either has a certain property or not at a given time; the God-man doctrine asks us to accept a unique case where an entity had all human properties and all divine properties concurrently, something which has no analogy or experimental support in any natural phenomenon.

To crystallize the scientific perspective, consider the following incompatible pairs of attributes that Jesus is claimed to have:

- Knowledge: A human mind that learns and has limited knowledge vs. an omniscient mind that knows all things.

- Spatial Presence: Being located in one place with a physical body vs. being omnipresent (present everywhere in space).

- Power: Living with normal human physical limits (fatigue, needing food, not moving mountains at will) vs. possessing omnipotence (unlimited power over nature).

- Mortality: Having a perishable human body that can suffer and die vs. being immortal and impassible, incapable of death or suffering.

- Mutability: Experiencing change and growth (baby to adult, learning, feeling emotions) vs. immutable divine nature that cannot change.

Each of these contrasts highlights why, from a logical scientific viewpoint, full humanity and full divinity are radically different states. No known entity could embody both sets of characteristics at once. Attempts to solve the conflict invariably limit or compartmentalize one side or the other (e.g. “Jesus didn’t use his omnipotence” or “Jesus’ human mind didn’t access his omniscience”). Those solutions imply that Jesus was not actively functioning with both natures fully operational in the same moment – effectively conceding the incompatibility in practice. Thus, a rigorous analysis suggests that Jesus cannot be literally “fully human and fully God” in the same moment without some form of logical or scientific violation. It remains, as believers say, a mystery of faith rather than a condition that one could model within our philosophical or scientific frameworks.

Comparative Theology

How have various Christian traditions and theologians dealt with this paradox? Contemporary orthodox Christianity (including Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Orthodox branches) affirms the Hypostatic Union as a non-negotiable mystery of faith: Jesus Christ is one person with two natures, truly God and truly man. Throughout history, however, there have been different interpretations and challenges to this doctrine. Some early Christian sects found the dual-nature concept so perplexing that they tilted to one side, either denying Christ’s full divinity (to preserve God’s transcendence) or denying his full humanity (to preserve his deity). These were deemed heresies by the early Church Councils. Understanding these differing perspectives – both orthodox and heterodox – will shed light on why the incarnation doctrine developed as it did and how it continues to spark theological debate.

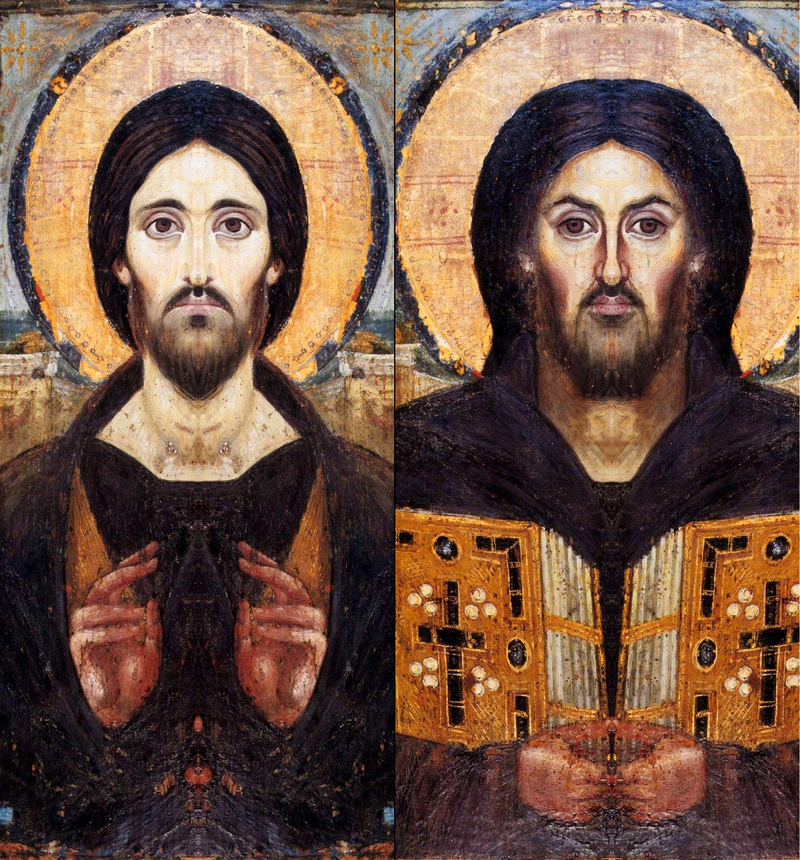

This ancient artwork reflects the Chalcedonian faith that Jesus is at once fully human and fully divine. The Catholic, Orthodox, and historic Protestant churches all embrace this view. They teach that “Jesus Christ is true God and true man”, one person in two natures. For example, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states that “He became truly man while remaining truly God. Jesus Christ is true God and true man”. Eastern Orthodox liturgy and icons (like the one above) constantly affirm this mystery. Classical Protestant confessions (e.g. the Westminster Confession) likewise uphold that Christ, the Son of God, “who is very and eternal God… did take upon him man’s nature.” In essence, all major branches stemming from the early Church councils agree on this Chalcedonian formula. They consider it a profound mystery but essential for Christian salvation: Jesus had to be fully human to represent us and experience death, and fully God for that death to have infinite worth and to overcome sin and death. This unified teaching is often summed up in the term “Hypostatic Union”, and it underpins doctrines like the atonement (God redeeming humanity by entering into it) and the Trinity (the Son is God become man).

Despite this consensus in official doctrine, historical theological positions have varied, especially in the early centuries. Two notable heresies that arose (partly in attempt to solve the paradox) were Arianism and Docetism, which took opposite tacks: one denied Christ’s full divinity, the other denied his full humanity.

Arianism: Denying Full Divinity to Solve the Paradox

Arianism was a 4th-century Christological heresy associated with Arius, a priest from Alexandria. Arius taught that the Son of God was not co-eternal with the Father and not of the same substance. In effect, Jesus (the Son) was a heavenly creature – exalted above humans, but still created by God and subordinate to the Father. Arians believed “there was a time when the Son was not”, meaning the Son had a beginning. This implies Jesus is not infinite or eternal by nature. He could be called “divine” in a honorific sense, but not God in the fullest sense – more like a semi-divine hero or demigod. By denying the Son’s co-equal divinity, Arius effectively eliminated the infinite-infinite contradiction: Jesus was not literally God Almighty incarnate, but a lesser being who became human. If Jesus isn’t fully God, the logical contradictions (omniscience vs ignorance, etc.) are softened because Jesus never had all those divine attributes to begin with (according to Arians). In Arianism, Christ could still be seen as “perfect man,” but his “divinity” was of a different kind – derived and not absolute.

The orthodox church rejected Arianism vehemently at the Council of Nicaea (325 AD). From the orthodox perspective, Arianism solved the philosophical problem at too great a theological cost. It “struck at the foundations of Christianity”, because if Christ is not truly God, then God did not truly unite with humanity. The incarnation would be just figurative – a great prophet or angelic being took on flesh, but not God Himself. The core Christian idea that “God became man so that man might be united with God” (as Church Fathers like Athanasius argued) would collapse. Also, only God has the power to save in the fullest sense; a creature, no matter how exalted, could not accomplish the redemption of all humanity. Thus, while Arianism made Jesus more logically palatable (avoiding a God-man contradiction by making him a kind of super-creature-man), it was declared a heresy because it denied Jesus’ full divinity and undermined the very idea of God’s incarnation and the Trinity.

Interestingly, Arian-like thinking does reappear in various forms even in modern times (e.g. Jehovah’s Witnesses have a Christology similar to Arianism, considering Jesus an archangelic being, not equal to Jehovah). Such views often arise from the difficulty of the orthodox position – they choose coherence over mystery, but in doing so depart from the mainstream Christian confession that Jesus is fully God.

Docetism: Denying Full Humanity to Solve the Paradox

On the flip side, Docetism (from Greek dokein, “to seem”) was an early heresy (emerging in the 1st–2nd centuries, often associated with Gnostic sects) that denied the real humanity of Jesus. Docetists taught that Christ only appeared to have a physical body and to suffer, but in reality he was purely divine or spirit. They viewed matter and flesh as either illusory or unworthy of the divine, so the Son of God would not truly subject himself to the limitations of a human body. According to Docetism, “Jesus Christ only seemed to be human.”

For example, some said that during the crucifixion, Christ did not actually feel pain or truly die; it was like an apparition or a phantasmal projection that people saw. In essence, Docetism solved the Incarnation paradox by discarding the full reality of the Incarnation – Jesus’ “humanity” was a mirage. If Jesus wasn’t really human, then there is no contradiction in him being fully divine, because the messy human attributes were never truly applied to him. He was God walking the earth in disguise, not actually taking on human weakness.

The Church also roundly condemned Docetism. It contradicted the apostolic teaching that “the Word became flesh” (John 1:14) and the insistence in 1 John 4:2 that “Jesus Christ has come in the flesh” (which directly combats an early docetic tendency). Orthodox theology insisted Jesus had a real human body and a rational human soul – in every way human except sin. Early critics like Ignatius of Antioch (2nd century) attacked the Docetists, emphasizing that Jesus truly hungered, suffered, and died. The rationale for rejecting Docetism is clear: if Christ was not truly human, then he did not truly unite himself to our condition, and thus our humanity is not healed or saved. The sufferings of Christ would be meaningless pantomime if he didn’t actually experience pain or death. In Christian doctrine, to save humans, Christ had to assume what is ours – including the ability to suffer and die – and then overcome it in the resurrection. A merely divine apparition cannot truly die or rise, and therefore cannot truly conquer death on our behalf. Additionally, the moral example of Jesus and his empathy as High Priest (as described in the New Testament) rely on him genuinely partaking in human struggles. Docetism, by denying Jesus’ humanity, empties the incarnation of its love and solidarity – it makes God a deceiver who pretends to be human but isn’t really with us.

Thus, while Docetism dodged the “how can God suffer or not know things?” question by saying “Jesus’ humanity wasn’t real,” it was rejected for undermining the Gospel at its core. Orthodox Christianity chose to tolerate unresolved paradox (God suffering in Christ, God dying in Christ) rather than give up the reality of either nature.

Other Christological Views and Ongoing Debates

Between these two extremes, other historical positions tried to explain the God-man union in different ways – each with its own implications:

- Nestorianism: Emphasized the separation of natures so much that it spoke almost of two persons (the divine Logos and the human Jesus of Nazareth loosely united). Nestorius wanted to safeguard that God cannot have a mother or suffer, so he taught that Mary birthed the man Jesus, and then the Logos indwelt him like a temple. This was condemned for splitting Christ – orthodoxy insisted Mary is Theotokos (God-bearer) because the one person she bore is God incarnate, not just a man with God alongside. Nestorian logic reduces the contradiction by making the union more like a partnership, but it fails to affirm that one person is both God and man.

- Monophysitism (Eutychianism): Went the opposite direction, saying after the union, Christ really had one nature – the divine and human fused into a single new nature (often described as the human being absorbed like a drop in the ocean of divinity). This solves contradiction by effectively eliminating the full distinction of the human: Jesus becomes a hybrid, mostly divine. The Church rejected this too at Chalcedon, insisting the natures remain distinct. If Christ isn’t fully and distinctly human, then he isn’t a true representative of humanity.

- Miaphysitism: (Held by Oriental Orthodox churches like the Coptic and Syrian, stemming from St. Cyril’s theology) – they speak of one united nature “from two” – fully divine and fully human but united. They differ semantically from Chalcedon but still reject either/or extremes. They emphasize the unity more, Chalcedon emphasizes the duality within unity. These nuances show how delicate the balancing act was and is.

In modern theology, the mystery of the incarnation is still discussed and debated. Kenotic Christology, as mentioned, is one modern approach where theologians propose that the Son voluntarily laid aside the exercise of certain divine attributes in order to live a genuinely human life. This allows Jesus to be fully human in experience (solving some logical issues) at the cost of saying, during that period, the Son wasn’t manifesting full omnipotence, omniscience, etc. Classical theists, however, often reject kenosis as incompatible with God’s unchangeable nature. They prefer to stress that the incarnation is a mystery – rationally inexplicable but true. Some argue that human logic and science simply cannot comprehend God’s mode of being, so what appears contradictory to us might be resolved at a higher order of reality. This appeal to mystery is essentially an admission that the union of infinite and finite breaks our categories, and thus one must accept it on faith rather than clear reasoning.

The implications for Christian doctrine of how one views this issue are huge. If one abandons the full dual nature (like Arianism or Docetism did), then key doctrines like the Trinity, Atonement, Resurrection, and Salvation change drastically. Christianity built its theology on the paradox: “Remaining what he was, he became what he was not,” as an old formula says. The early church determined that only by affirming both could the fullness of Christ’s work be preserved – even if it led to an apparent contradiction. This has led to an enduring tension between faith and reason in Christianity: Reason might say “this cannot be,” but faith says “with God all things are possible, even an astounding union of opposites.”

Modern debates sometimes revisit these questions: Could Jesus have been mistaken about something (human ignorance)? Did he have two wills (the church later said yes, a human will and a divine will – another duality)? How do we understand Jesus’ cry of abandonment on the cross (“My God, why have you forsaken me?”) – is it God forsaking God? Such issues show that the conversation is not merely academic; it affects how believers relate to Jesus. If he is not truly human, can he really sympathize with our weaknesses? If he is not truly God, can he truly save and be an object of worship? Christianity’s answer has been to embrace the hypostatic union as a holy mystery, even if it transcends rational analysis.

Conclusion

Analyzing the proposition that “Jesus is both a perfect man and fully divine” from philosophical and scientific perspectives reveals why it is often deemed an incoherent or paradoxical claim. Philosophically, it runs up against the law of non-contradiction – requiring one entity to have two sets of attributes that logically cannot coincide (finite/infinite, temporal/eternal, mutable/immutable, etc.). Metaphysically, it challenges our understanding of essence and personhood, positing a unique case that defies the normal one-to-one relationship between a person and a nature. Scientifically, when we consider the incarnation through the lenses of cognitive science, physics, and biology, we find numerous practical incompatibilities: a single person with two minds, a body bound by space and a presence that is everywhere, a living organism that can die yet supposedly cannot die – all these are contradictions if taken at face value.

The historical theological journey underscores that Christians themselves recognized the tension – the early heresies were, in a sense, attempts to make sense of the senseless (to rationalize the incarnation by eliminating one pole). The ultimate orthodox stance was to refuse to surrender either truth, holding them together in tension. This has led to the incarnation being labeled a “mystery” or “paradox” rather than a tidy logical proposition.

For a reader interested in philosophy, science, and theology, the incarnation of Christ presents a fascinating case study where the limits of human reason collide with the assertions of faith. Philosophically and scientifically, one is pressed to conclude that a being cannot be both fully God and fully man in the same sense at the same time – the concepts are just too opposite. And yet, Christian doctrine unabashedly affirms this very conjunction. This has forced thinkers either to embrace a degree of logical dissonance (calling it a divine mystery beyond comprehension) or to redefine the terms in hopes of resolving the contradiction (with varying results, often deemed heretical or heterodox by the mainstream).

In the end, whether Jesus can or cannot be both perfect man and fully divine boils down to one’s epistemology and perspective. From the standpoint of human philosophy and science alone, the answer leans toward “cannot” – it is an untenable union by our standards of coherence. As one analysis put it, asserting a being with such dual nature without contradiction is as problematic as claiming a shape that is a square and a circle at once. However, within Christian theology, the answer is that he is, despite the contradiction – and this is embraced as a profound truth that surpasses ordinary reason. This tension has not been “solved” in any satisfactory logical way; it remains a point where, as the early church might say, reason bows to mystery. For critical inquiry, this means the incarnation will continue to be a topic of analysis and debate, illustrating the broader challenge of reconciling faith claims with philosophical and scientific scrutiny. Each reader must consider how much paradox one is willing to tolerate, and whether truth can transcend the constraints of Aristotelian logic and scientific law in this unique case of the God-Man.

The Quranic wisdom as quoted in the verses as epigraph is an emphatic “no.” According to the Glorious Quran Jesus is human, an honored prophet, but not divine.

Sources:

The logical formulation of the contradiction is adapted from common critiques of the incarnation krisispraxis.com, and philosophers like Stephen Law have highlighted the incompatible properties (e.g. omniscience vs learning, immortality vs death) in sharp terms stephenlaw.blogspot.com. The cognitive and physics issues draw on theological discussions of Jesus’ knowledge and presence reknew.org. Definitions of heresies are based on historical summaries – Arianism denied Christ’s full divinity hardonsj.org, while Docetism denied his real humanity thirdmill.org – both deemed insufficient by orthodox Christianity thirdmill.org. The Chalcedonian position of two natures united in one person is stated in the creed and upheld across Christian traditions britannica.com, even as it is recognized as a mystery that defies full human understanding stephenlaw.blogspot.com.

Leave a comment