Epigraph

God takes the souls of the dead and the souls of the living while they sleep –– He keeps hold of those whose death He has ordained and sends the others back until their appointed time –– there truly are signs in this for those who reflect. Yet they take intercessors besides God! Say, ‘Even though these have no power or understanding?’ (Al Quran 39:42-43)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

The verses quoted as epigraphs use the metaphor of sleep and death to explain each other. As sleep is reversible, so is death in the sense of the Afterlife. We are not our own creators; God, who has created us with our sleep cycles, also guarantees life after death. If He has created mechanisms to restore our consciousness from sleep, He would have provided to back up our consciousness that would survive the physical death of our bodies and to restore our first-person consciousness in another body of His choosing in Afterlife. What can we learn from sleep in what is to come?

Sleep is a dynamically regulated state of reduced consciousness that remains distinct from pathological unconsciousness (coma) or extreme metabolic depression (hibernation). Multiple overlapping mechanisms in the nervous system and body ensure that normal sleep does not “deepen” uncontrollably into life-threatening inactivity. This article explores how the brain’s arousal centers, metabolic limits, and reflexes maintain sleep within safe bounds, and how sleep differs fundamentally from hibernation and coma.

Neurological Regulation: Balancing Wakefulness and Sleep

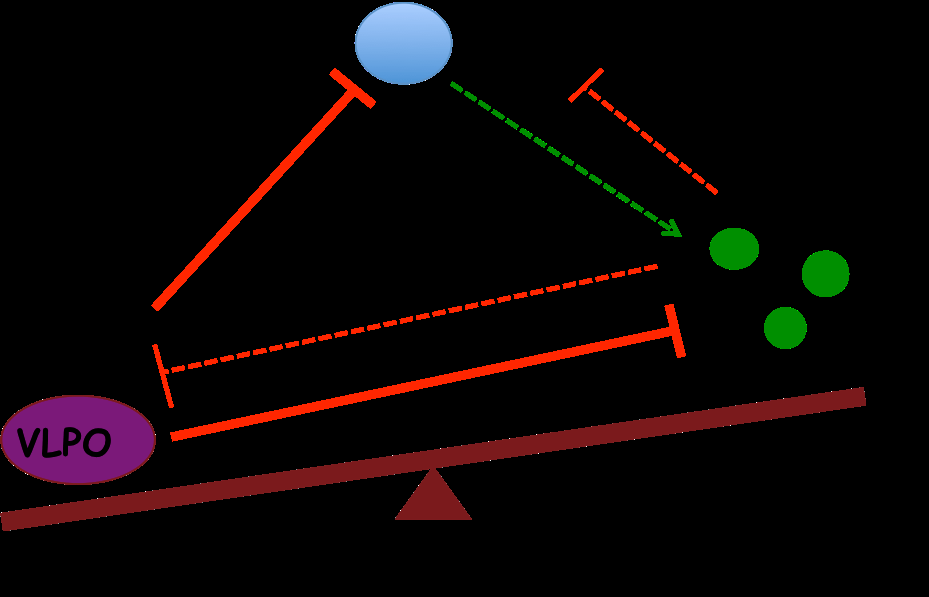

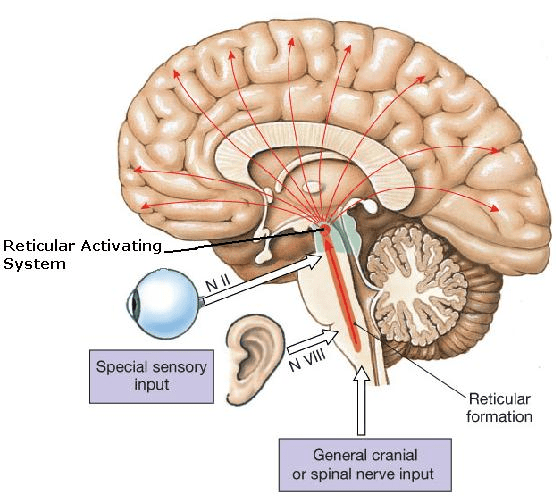

Brainstem and Hypothalamus Control: Deep in the brain, structures like the brainstem and hypothalamus act as command centers that toggle between wakefulness and sleep. The brainstem’s reticular activating system (RAS) sends ascending signals that keep the cortex aroused and conscious. Conversely, a sleep-promoting region in the anterior hypothalamus (the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, VLPO) can suppress these arousal signals. Under normal conditions, these areas work in a push-pull manner, ensuring the brain cycles through wake, non-REM, and REM sleep in a controlled fashion.

Wakefulness is maintained by neurons in the pons, midbrain, and posterior hypothalamus that release excitatory neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, histamine, and orexin) to activate the cortex.

As we fall asleep, VLPO neurons (which release the inhibitory transmitter GABA) shut down these arousal centers, allowing non-REM (NREM) sleep to deepen. Later, specialized neurons in the pons take over to generate REM sleep, a stage in which the EEG resembles wakefulness but the body is paralyzed. Importantly, the transitions between states are abrupt and tightly regulated – a “flip-flop” switch mechanism – rather than a slow drift into unconsciousness.

Wake-Promoting Neurotransmitters: Several brain chemicals actively prevent sleep from becoming too deep. For example, neurons of the locus coeruleus secrete norepinephrine and those of the dorsal raphe nucleus secrete serotonin; these are highly active during wakefulness, fall silent in deep sleep, and help terminate REM sleep.

Orexin (hypocretin), a neuropeptide from the lateral hypothalamus, plays a critical stabilizing role. Orexin neurons fire during wakefulness and excite the other arousal centers (like the locus coeruleus and raphe), helping maintain an alert state. By activating these key centers, orexin prevents unwanted transitions into sleep. In essence, orexin acts as a “guard” against sleep becoming too deep or occurring at the wrong time. This is evident in narcolepsy, a disorder where loss of orexin leads to sudden sleep attacks – showing how crucial orexin normally is in keeping sleep/wake balance (discussed more later). Other transmitters like acetylcholine (from the basal forebrain and pons) become especially active during REM sleep to activate the cortex, ensuring that even in sleep, the brain never shuts down completely. Overall, the reciprocal inhibition between wake-promoting neurons (brainstem/hypothalamus) and sleep-promoting neurons (VLPO) creates a stable toggle – you are either awake or asleep, but not in an indeterminate deepening state. This neurocircuit design prevents a gradual slide from normal sleep into coma.

Metabolic and Physiological Limits on Sleep Depth

Sleep is not just a brain state; it also involves whole-body changes in metabolism, temperature, and breathing. However, these changes are limited in magnitude – the body’s physiology resists any drift toward the extreme slowing seen in hibernation.

Thermoregulation: Humans maintain a nearly constant core temperature around 36–37°C, even during sleep. In fact, as we enter deep (slow-wave) sleep, our body temperature drops slightly – usually by only 1–2°C at most. This mild cooling is part of normal sleep and is linked to a slight lowering of metabolic rate. Crucially, the brain’s temperature control in the hypothalamus stays active during sleep. If the body cools too much, mechanisms like shivering or increased thyroid activity kick in; if it overheats, sweating or blood vessel dilation occur. This means the sleeper will not continue cooling indefinitely. In stark contrast, hibernating animals deliberately allow their body temperature to plunge dramatically to conserve energy. During hibernation, core temperatures can fall near freezing – for example, some small mammals may drop to −3°C, reducing energy use by up to 90%. Human physiology does not permit such extreme hypothermia during sleep. If a person’s environment causes dangerous cooling, they will either wake up feeling cold or the body will initiate autonomic responses to generate heat. Our built-in thermoregulatory responses thus prevent normal sleep from sliding into a torpid, hibernation-like state.

Energy Metabolism and Oxygen Supply: In sleep, the body’s metabolism slows only moderately. During deep NREM sleep, brain energy use may decline by roughly 20–30% compared to wakefulness, and overall calorie burning drops by only about 5–10% during the night. Breathing and heart rate become slower and more regular, which saves some energy, but critical oxygen delivery continues at a sufficient rate. The sleeping brain and organs still require a steady supply of oxygen and glucose – if these fall too low, protective mechanisms are triggered (as discussed next). Hibernation, again, is an extreme contrast: hibernating animals can survive on minimal oxygen consumption and vastly reduced circulation for days or weeks at a time. Humans cannot do this naturally; our neurons are too active and would be injured by prolonged oxygen deprivation or nutrient lack. For instance, in normal sleep, blood oxygen and carbon dioxide levels are tightly regulated by the brainstem respiratory centers. If CO₂ rises or O₂ drops beyond a threshold, the body will reflexively increase breathing or cause micro-arousals to prevent suffocation. This ensures that sleep does not deepen to the point where breathing is inadequate. Similarly, blood pressure typically falls at night, but not below safe levels – if it does, baroreceptor reflexes stimulate the heart to beat faster or release adrenaline to raise pressure. In short, human sleep occurs within a narrow homeostatic envelope. We have physiological floor limits on how slow and low our vital processes can go in sleep. Beyond those limits, the body will intervene by adjusting autonomic outputs or awakening us. These limits keep human sleep far above the level of metabolic suppression seen in true hibernation.

Human Sleep vs. Hibernation Cycles: Another key difference is duration and cycling. Human sleep is a nightly occurrence lasting hours, not an entire season. We cycle through NREM and REM stages roughly every 90 minutes. In contrast, animals in winter hibernation enter a prolonged multi-day torpor without REM (some hibernators do experience brief arousals between torpor bouts, possibly to achieve REM sleep and reset physiology). The fact that our brains insist on REM sleep and regular cycling is itself a protective mechanism – it periodically raises the level of brain activity and autonomic function during the night, rather than allowing a continuous deepening. REM sleep features higher heart rate variability, almost no thermoregulation, and active dreaming; this prevents the body from ever staying in monotonously deep slow-wave sleep for too long. By morning, rising circadian signals (e.g. cortisol, light exposure) actively reverse the metabolic slowing of night, bringing us back to wakefulness. Evolution tuned our metabolism for daily activity and rest, not extended torpor. Thus, normal sleep has in-built time limits: after about 8 hours, homeostatic sleep pressure is largely dissipated and sleep naturally lightens. We do not simply keep descending into deeper unconsciousness – we either enter REM or wake up.

Protective Reflexes and Arousal Systems During Sleep

Even when we are asleep, the body and brain remain alert to potential danger or internal distress. A network of protective reflexes and arousal systems stands guard to keep sleep from becoming too deep or unresponsive.

Autonomic Arousals: The autonomic nervous system (ANS) continuously monitors critical physiological parameters during sleep and can trigger arousals (shifts to lighter sleep or brief awakening) if something deviates from normal. For example, if you experience an airway obstruction or pause in breathing (as in sleep apnea), CO₂ levels will rise in your blood. Specialized chemoreceptor neurons in the brainstem (in the medulla’s retrotrapezoid nucleus and elsewhere) sense this change and initiate a powerful arousal response. The sleeper will subconsciously breathe harder or wake up gasping, restoring normal oxygen. This CO₂-induced arousal reflex is literally life-saving – it prevents suffocation by ensuring you don’t remain in deep sleep without breathin. Similarly, if blood pressure falls too low, baroreceptors in arteries signal the brainstem to increase sympathetic activity, which can momentarily lighten sleep as heart rate increases. These reflexive responses keep vital signs within survivable limits. In fact, many of the micro-awakenings we experience each night (often without remembering them) are due to such protective autonomic triggers. While they may fragment sleep slightly, they serve to prevent “pathologically” deep sleep that would threaten homeostasis.

Sensitivity to External Stimuli: Unlike coma patients, sleeping people still respond to the outside world to some degree. Our sensory organs continue to sample the environment, and the brain’s RAS remains poised to react. Strong or significant stimuli will cause the RAS to lift the brain out of deep sleep. For instance, a sudden loud noise or a touch will often jolt a person into lighter sleep or full wakefulness. Even sleepers in slow-wave (deep) sleep can be awakened by sufficiently intense sound or pain – it is harder, but possible, which is why deep sleep is reversible. External triggers that commonly interrupt sleep include:

- Noise: Unexpected loud sounds (an alarm clock, a baby crying, a door slam) are detected by the ears and relayed to the brainstem, quickly activating arousal pathways. The sleeping brain can filter out some benign background noise, but will react to loud or meaningful sounds (like hearing one’s name called).

- Light: Changes in light, especially bright light, can penetrate the eyelids or be sensed by photosensitive retinal cells. Light signals reach the hypothalamus (suprachiasmatic nucleus) and suppress melatonin. This can cause early-morning awakening – an evolutionary trait to wake at sunrise. A sudden light (turning on the room light) often wakes someone because the brain interprets it as daytime.

- Temperature Change: If the environment becomes uncomfortably hot or cold, the skin and hypothalamus sense it. Excess heat can cause sweating and restlessness that disrupt sleep, whereas cold triggers shivering or discomfort that may arouse the person to add blankets or move. These reactions prevent the body from drifting into dangerously low or high body temperatures during sleep.

- Pain or Discomfort: Any internal discomfort – a full bladder, muscle cramps, indigestion, or pain from an injury – will tend to wake the brain. For example, a sleeper will often awaken to use the bathroom, or toss and turn to relieve pressure on a sore shoulder. This is a protective mechanism to address bodily needs rather than remaining unconscious through them.

- Touch: Light touch might be incorporated into dreams, but a vigorous shake or something crawling on the skin will usually wake a person. This reflex likely evolved to alert us to insects or threats even while asleep.

Arousal Thresholds: The threshold for awakening varies with sleep stage – it’s highest in stage N3 (deep NREM) and lowest in lighter stages. But even in the deepest NREM, the brain will awaken if stimuli are strong enough (or if the stimulus is interpreted as dangerous). We’ve all experienced momentary awakenings due to a thunderclap or an alarm during deep sleep. These built-in arousal systems stop sleep from ever becoming so deep that the brain disconnects completely. In fact, researchers define sleep (as opposed to coma) by this very responsiveness: sleep can be interrupted by external stimuli, whereas coma cannot. Thus, our evolutionary wiring keeps us attuned to the environment: a sleeping animal can be roused to flee from a predator or attend to a baby’s cry. This responsiveness is a crucial protective factor that prevents normal sleep from resembling the unresponsive oblivion of coma or brain death.

Differences Between Sleep, Hibernation, and Coma

To appreciate how sleep is kept from deteriorating into a pathologically deep state, it’s useful to compare the characteristics of sleep vs. hibernation vs. coma. Each state has distinct patterns of brain activity, metabolism, and reversibility:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) Patterns: Normal sleep has a highly organized EEG profile, cycling through predictable stages. Early in the night, NREM sleep shows progressively slower, higher-amplitude brain waves (delta waves in stage N3). Later, REM sleep has fast, low-amplitude EEG activity resembling wakefulness. In a coma, by contrast, these sleep-specific patterns disappear. Comatose patients usually exhibit diffusely slowed, steady EEG activity or even flat traces in severe cases. They do not cycle through REM/NREM stages. Some comas (e.g. “alpha coma” or “spindle coma”) can show patterns that superficially resemble certain sleep stages (like alpha waves or even sleep spindles), but these do not progress in the normal sequence. Crucially, REM sleep is absent in deep coma. Hibernation is a unique case: during torpor, brain waves often become very slow and of low amplitude, somewhat like deep NREM sleep, and EEG overall is greatly suppressed. However, hibernating animals do show periods of “sleep-like” EEG when they periodically warm up – they may even exhibit some NREM sleep during torpor, but typically no normal REM until arousals occur. Overall, sleep EEG is cyclic and responsive, whereas coma EEG is static and unresponsive, and hibernation EEG is profoundly slowed for long durations.

- Level of Consciousness and Responsiveness: By definition, sleep is readily reversible – a sleeper can be awakened by stimuli or will self-awaken after a few hours. In sleep, the brain still processes some external information (we might incorporate noises into dreams or respond to our name). In a coma, consciousness is abolished and cannot be aroused by any stimulus, not even painful ones. A comatose brain has either severely depressed activity or is functionally disconnected from sensory input. The absence of wake-up capability is a fundamental difference. Hibernation might seem similar to coma in that the animal is extremely unresponsive, but it is actually a controlled, reversible state orchestrated by the animal’s brain. Hibernating animals do occasionally rouse (often slowly, over hours) to lighter torpor or brief wakefulness before resuming torpor. Importantly, coma is pathological – caused by injury, drugs, or illness – whereas hibernation is an adaptive physiological state. A hibernating animal can eventually wake up on its own when internal signals say it’s time (e.g. when spring arrives), but a comatose patient cannot wake without recovery of brain function. In summary: sleeping persons can be awakened; comatose patients cannot; hibernating animals will awaken only after prolonged torpor or with specific triggers (like ambient temperature changes).

- Metabolic Rate and Physiological Functions: In sleep, as noted, metabolism dips modestly. Heart rate and breathing slow but remain in a normal range, and the sleeper cycles between deeper and lighter phases. In hibernation, metabolism is in an extreme low-power mode – heart rate may drop to just a few beats per minute, and breathing can pause for minutes or hours. Yet the hibernator’s brain orchestrates this safely by drastically lowering energy needs and preventing waste buildup. Humans cannot achieve this metabolic suspension naturally. In a coma, metabolic activity of the brain is usually below normal sleep levels (because parts of the brain are damaged or suppressed). For example, PET scans show brain glucose use in coma can be 50% of normal wakefulness or less – comparable to or even lower than deep NREM sleep, which is about 60% of wake metabolism. However, unlike hibernation, in coma this low metabolism is not well-regulated or beneficial; it’s a result of dysfunction. Also, many autonomic functions in coma are impaired – e.g. coma patients often need medical support for breathing or blood pressure, whereas a sleeper’s body self-regulates perfectly well. Brain death, the extreme end of the spectrum, means zero brain activity (flat EEG) and no brain-driven respiration or reflexes. Normal sleep never even approaches that condition – the brainstem in sleep remains fully functional, driving respiration and reflexes. Indeed, the capacity for reflexes (like coughing, swallowing, reacting to acid in the blood) is maintained during sleep but lost in deep coma or brain death.

- Arousal Mechanisms: Sleep and coma differ in what it takes to transition back to wake. A sleeper can be awakened by sufficient stimulation or simply by the brain’s internal clock and homeostatic drive once the need for sleep is satisfied. Sleep has an internal limit – after a certain amount of deep sleep, the pressure for it dissipates and REM or wake ensues. In coma, the arousal systems are either non-functional or actively inhibited by damage, so there is no clear trigger to “exit” the state (recovery, if it occurs, happens gradually as the brain heals). Hibernation has a built-in arousal process: e.g. hormonal changes and hypothalamic signals will periodically bring the animal out of torpor (often into a lighter sleep or short awake period) before it goes back under. In humans, the reticular activating system ensures that even during deep NREM sleep, there is a baseline level of reticular formation activity that can quickly ramp up. This prevents the brain’s activity from ever flatlining as it would in a coma. As one source succinctly puts it: “Sleep is a state that is relatively easy to reverse (this distinguishes sleep from other states of reduced consciousness, such as hibernation and coma).” Our neurobiology guarantees that sleep stays on the safe side of the line separating it from coma.

In summary, sleep is an actively managed, cyclic state with moderate metabolic depression and maintained reflexes, whereas coma is an unregulated pathological suppression of brain function, and hibernation is a profound but controlled metabolic downshift that humans did not evolve to enter. The brain’s safeguards (both neural and physiological) keep normal sleep within a reversible, homeostatic range, never approaching the point of no return that characterizes coma or brain death.

Medical and Evolutionary Insights

Why Humans Don’t Hibernate: From an evolutionary perspective, humans (and most large primates) lost any ability to hibernate long ago, likely because it conferred no survival advantage in our ancestral environment. Early humans lived in climates and circumstances where food could be gathered year-round or they could migrate to avoid the worst shortages, so entering a months-long torpor was not necessary. In fact, extended hibernation would have serious downsides for a human. Consider that while in torpor or hibernation an animal cannot eat, move, or defend itself. For humans (a social, big-brained animal), such a state would interfere with survival and reproduction. Key evolutionary reasons why natural human hibernation was selected against include:

- Reproductive Disadvantage: A hibernating human would not be bearing or raising children for that entire period. If an individual spent many months in torpor, they would miss opportunities to mate and care for offspring. Competing humans who remained active year-round could out-reproduce those in long sleep, eventually outnumbering them.

- Predation and Safety: While hibernating in a helpless state, a human would be extremely vulnerable to predators or hostile humans. Unlike small burrowing animals, early humans couldn’t easily hide for months without detection. Being unable to respond or escape would be fatal in many cases. Only species with safe hiding spots (like caves or deep burrows) and smaller nutrient needs evolved true hibernation.

- Energy Trade-offs: Humans have large brains that consume a lot of energy even at rest. There is speculation that ancient human ancestors might have had some torpor ability, but maintaining brain health during a long hibernation is challenging. Warming up periodically to sleep (as hibernators do) would incur energy costs that might negate the benefits for a human-sized animal. It likely proved more efficient for humans to stay active and forage or store food than to undergo prolonged torpor. In evolutionary terms, any genes enabling hibernation may have been lost because individuals who didn’t hibernate thrived better.

That said, scientists are studying induced torpor in humans for medical or space travel purposes. We do have the basic metabolic pathways to lower body temperature and metabolism (e.g. doctors use therapeutic hypothermia in cardiac arrest patients to protect the brain). But naturally, our species sticks to the sleep-wake cycle instead of hibernation. Sleep gives us restorative benefits overnight without the severe risks and trade-offs of torpor.

Sleep Disorders and the Edge of Pathology: Studying certain sleep disorders can illuminate how the body normally protects against overly deep or prolonged sleep. Narcolepsy is one example mentioned earlier – it results from loss of orexin neurons and leads to an unstable flip-flop switch. Patients inadvertently fall straight into REM sleep from wakefulness and have trouble maintaining long, consolidated wake periods. Despite this, narcoleptics do not “sleep to death” or anything of that sort; other arousal systems (like adrenaline during strong emotions, or sensory input) can still wake them. What narcolepsy shows is how orexin normally prevents inappropriate or excessive sleepiness – without it, the brain can slip toward sleep at the wrong times. Treatments for narcolepsy often include stimulants or recently, orexin-receptor agonists, aiming to reinforce those arousal pathways.

Another condition, idiopathic hypersomnia, is characterized by an inability to stay awake and a propensity for very long sleep episodes. Research suggests that people with this disorder may have an overactive inhibitory system in the brain (possibly too much GABA signaling). In essence, their brain’s brakes (sleep-promoting signals) are too strong. Yet even in severe hypersomnia, patients still wake up eventually to eat, drink, and so on – the fundamental homeostatic triggers remain intact. This indicates that multiple layers of regulation (hormonal, neural, metabolic) need to fail for sleep to deepen to dangerous levels. In encephalitis lethargica (a historical illness that caused extreme sleepiness), patients would sleep 20+ hours a day, but again they could be awakened and their vital functions continued under oversight. Only when vital brainstem centers are damaged (as in certain stroke or brain injury) do we see sleep crossing into coma territory.

Conversely, there are disorders that reduce the ability to sleep deeply – for example, fatal familial insomnia (FFI), where damage to the thalamus prevents normal sleep and leads to death from sleep deprivation. This illustrates the opposite danger: without the ability to obtain deep sleep, the body and mind break down. Thus, the brain must maintain a goldilocks zone – not too little sleep, but also not too deep or long. The balance is normally struck via robust feedback loops. If one system falters, others compensate. For instance, if the monoamine (NE/5-HT) arousal systems are suppressed (say by sedative drugs), the buildup of CO₂ will still trigger breathing arousal, or external stimuli can penetrate if loud enough. It usually takes potent anesthetics or severe injury to override all arousal pathways and induce a coma-like state.

Epilogue

In summary, human sleep is kept in check by an interplay of neurological, physiological, and environmental factors honed by evolution. Our brain’s arousal centers continuously oppose the sleep centers to prevent overshooting into coma. Our metabolism and autonomic reflexes impose floor limits that stop sleep from becoming hibernation. And our senses and reflexes stand by to wake us if something goes awry. These mechanisms ensure that sleep remains a reversible, safe, and daily phase of reduced consciousness – one that provides rest and recovery, but from which we can reliably emerge each morning, ready to resume consciousness. Sleep is thus a tightly regulated state, distinct from the prolonged oblivion of hibernation or the pathological silence of coma, by design of nature and necessity for survival.

God who has provided such detailed and complex mechanisms and checks and balances for sleep and hibernation would have also provided back up mechanisms for our consciousness to be restored in Afterlife. Science does know of these mechanisms yet but can at least speculate about in terms of extra dimensions of the string theory.

Sources:

- España, R.A., & Scammell, T.E. (2011). Sleep Neurobiology from a Clinical Perspective. Sleep, 34(7): 845-858. periodicos.capes.gov.brperiodicos.capes.gov.br

- Social Sci LibreTexts. 10.3: Stages of Sleep. (n.d.). socialsci.libretexts.orgsocialsci.libretexts.org

- Neurolaunch (2024). Coma vs. Normal Sleep: Key Differences. neurolaunch.comneurolaunch.com

- Harvard Medical School – Sleep Health Education Program. Characteristics of Sleep. (n.d.). sleep.hms.harvard.edu

- Healthline (2022). Can Humans Hibernate? healthline.comhealthline.com

- Neurolaunch (2024). Orexin and Sleep-Wake Stability. neurolaunch.comneurolaunch.com

- SleepSnippets Blog (2015). The Flip-Flop Switch. sleepsnippets.wordpress.com

- Neurolaunch (2024). Sleep Arousal Causes and Mechanisms. neurolaunch.com

- J Neurosci (2018). Smith et al. CO₂-Induced Arousal from Sleep. jneurosci.org

- Noirhomme, Q. et al. (2009). Sleep vs. Coma. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 3(3): 401-407. orbi.uliege.beorbi.uliege.be

- Hypersomnia Foundation (2020). GABA-A and Idiopathic Hypersomnia. sleepfoundation.org

- Healthline (2020). Why Humans Don’t Hibernate – Evolutionary Perspective. healthline.comhealthline.com

Leave a comment