Epigraph

“Allah! There is no god ˹worthy of worship˺ except Him, the Ever-Living, All-Sustaining. Neither drowsiness nor sleep overtakes Him. To Him belongs whatever is in the heavens and whatever is on the earth. Who could possibly intercede with Him without His permission? He fully knows what is ahead of them and what is behind them, yet they encompass nothing of His knowledge except what He wills. His Throne (Kursī) extends over the heavens and the earth, and the preservation of both does not tire Him. For He is the Most High, the Supreme.” – Quran 2:255

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

We all see the world through a certain prism made of our ideology or prior set of ideas. Most prominent scientists, mathematicians and philosophers these days are atheist and see the world through a lens or prism of not only methodological naturalism but also ontological naturalism and so no matter what they may observe their lack of belief in God never changes.

But, if we see the quantum mechanics and especially quantum entanglement through the prism of God of Kaaba, God of the Quran then these latest discoveries confirm a very different reality.

This article examines how quantum entanglement and the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics support Al-Ghazali’s doctrine of occasionalism and the concept of God as the continuous sustainer of the universe. This will include comparisons with classical views on causality, an analysis of quantum nonlocality and Bell’s theorem, and discussions on modern theological interpretations of occasionalism and quantum mechanics.

Introduction

Quantum entanglement is a fundamental phenomenon in quantum mechanics where two or more particles become interconnected such that the state of one particle instantaneously influences the state of another, regardless of the distance separating them. This concept challenges classical notions of locality and has been a subject of extensive research and experimentation.

The reality of quantum entanglement has been substantiated through numerous experiments over the past several decades. One of the pioneering figures in this field, physicist Alain Aspect, conducted experiments in the early 1980s that provided strong evidence supporting the existence of entanglement. These experiments demonstrated correlations between entangled particles that could not be explained by classical physics alone.

In 2022, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger for their groundbreaking experiments with entangled photons. Their work established the violation of Bell inequalities, reinforcing the non-local characteristics of quantum mechanics and providing robust evidence for the phenomenon of entanglement. Recent studies have continued to validate and explore the implications of quantum entanglement. For instance, researchers have observed entanglement in top quark pairs produced in high-energy proton-proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider. This observation extends the evidence of entanglement to fundamental particles at unprecedented energy scales.

Additionally, experiments have demonstrated quantum interference between light sources separated by vast distances, such as 150 million kilometers. These studies highlight the non-local nature of entanglement and its potential applications in quantum communication and computing.

The confirmation of quantum entanglement has profound implications for various fields, including quantum computing, cryptography, and fundamental physics. Entanglement enables the development of quantum networks and has been utilized in experiments involving quantum teleportation, where the state of a particle is transferred instantaneously to another distant particle. These advancements pave the way for the realization of a quantum internet and more secure communication systems. In summary, extensive experimental evidence has firmly established quantum entanglement as a real and fundamental aspect of nature. Ongoing research continues to uncover its complexities and potential applications, marking a significant milestone in our understanding of the quantum world.

Quantum physics has upended traditional notions of cause and effect, in ways that intriguingly resonate with medieval theological ideas. The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics honored experiments on quantum entanglement that defy classical “local realism,” showing that particles can influence each other instantaneously across vast distances. Centuries earlier, the Islamic theologian Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058–1111) advanced occasionalism – the doctrine that no events have inherent natural causes, and that God directly sustains every occurrence in the universe. This article explores how entanglement research, which rejects strict local causality, echoes al-Ghazali’s ideas. We will summarize the Nobel-winning findings on entanglement and Bell’s theorem, compare classical views of causality (Aristotelian, Newtonian, and Islamic philosophical) with occasionalism, and examine how quantum nonlocality and indeterminacy reinforce the notion of a continuously upheld reality. Modern theological perspectives – within Islam and beyond – shed further light on occasionalism in the age of contemporary physics.

Entanglement and the 2022 Nobel Prize: Rejecting Local Realism

Quantum Entanglement describes a mysterious linkage between particles: what happens to one instantaneously affects the other, no matter how far apart they are. Einstein skeptically called this “spooky action at a distance,” as it seemed impossible under his relativity principle that nothing travels faster than light. For decades, scientists debated whether entanglement was real or just an illusion caused by unseen hidden variables carrying pre-set instructions. In 1964, physicist John Bell devised a theoretical test (Bell’s theorem) to settle this: he derived an inequality that any local hidden-variable theory must obey, limiting how strongly two particles’ measurement results can correlate. Quantum mechanics, however, predicted those correlations could exceed Bell’s limit in certain experiments, violating his inequality. In other words, if entangled particles truly have no definite states until measured, their coordinated outcomes would be too well-aligned to be explained by any local realist model.

Beginning in the 1970s, John Clauser and colleagues performed the first experiments to test Bell’s inequality. By generating entangled photon pairs and measuring their polarizations, Clauser showed the correlations did violate Bell’s bound, supporting quantum mechanics and ruling out local hidden variables. Some physicists remained cautious, noting potential “loopholes” – for instance, maybe the experimental setup inadvertently selected special subsets of photons. In the 1980s, Alain Aspect improved these tests by switching the detector settings after the entangled photons were emitted, so no information about the settings could be known in advance. Aspect’s refined experiments conclusively closed the major loopholes and again found clear violations of Bell’s inequality, confirming that nature does not obey local realism. In the 1990s and 2000s, Anton Zeilinger pushed these tests further – entangling photons across long distances (even via satellites) and using random number generators or distant starlight to set detector angles – always with results upholding quantum theory’s nonlocal predictions.

The Nobel Committee in 2022 recognized Aspect, Clauser, and Zeilinger “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities”. Their combined work definitively showed that the universe is not locally real – entangled particles do not have independent properties determined ahead of time, and no signal constrained by lightspeed connects them. This has profound implications: it suggests that at a fundamental level, events can be correlated without any direct physical interaction. Such quantum nonlocality, once a theoretical curiosity, is now an experimental fact and even the basis for emerging technologies in quantum computing and cryptography. The classical worldview, in which objects have definite states and influence each other only through local contact or fields, turns out to be incomplete. Interestingly, this radical revision of causality offers a new lens to examine age-old philosophical and theological debates about how and by whom the world’s events are governed.

Classical Causality: Aristotle, Newton, and Islamic Philosophers

Aristotle’s view of causality (taken up by later Islamic peripatetic philosophers like Ibn Sina/Avicenna and Ibn Rushd/Averroes) held that events in nature have intrinsic causes. Aristotle famously described four types of causes (material, formal, efficient, final); for physical events, an efficient cause produces its effect by actualizing a potential. In this classical picture, when the conditions for a cause are present, its effect follows by necessity – for example, a spark igniting gunpowder will necessarily cause an explosion if all requisites are met. Medieval Aristotelians believed God created the world with an intelligible order, but they saw secondary causes (natural causes) as real and reliable. Avicenna taught that once God grants existence to entities with certain natures, those natures will behave regularly – fire will burn cotton when in contact – unless God miraculously intervenes. Such views allowed for scientific knowledge: by observing cause and effect, one discovers the rules (ultimately given by the First Cause, God) that govern nature.

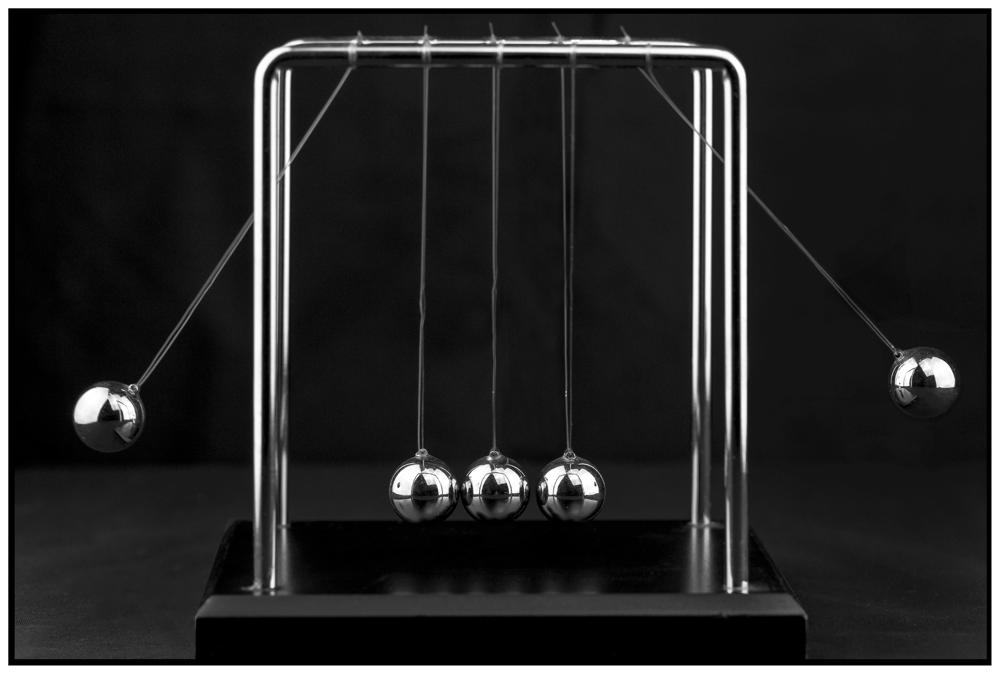

The Newtonian outlook further solidified belief in a lawful, deterministic causality. Sir Isaac Newton’s laws of motion (1687) and the classical physics that followed portrayed the universe as a vast clockwork. Every effect had a precise cause, and given complete information about the present, one could (in principle) calculate future outcomes exactly. Later thinkers like Pierre-Simon Laplace argued that an omniscient intellect could predict every future event from the laws of physics and initial conditions – a view known as determinism. In Newton’s own theology, God was the grand designer of the laws of nature and set the universe in motion, occasionally intervening with miracles, but mostly not needed for day-to-day running of the cosmic machine. This corresponds to concurrentist ideas in theology: God sustains the existence of creatures and concurs with their actions, but allows created things to have genuine causal powers. For example, a billiard ball striking another transfers momentum and causes the second to move – a straightforward chain of cause and effect that does not require direct divine intervention at each collision. The iconic Newton’s cradle device (a series of swinging spheres transferring impact) visually demonstrates this classical causality: each ball’s motion is entirely caused by contact with another, in line with conservation laws, needing no “extra” agency outside the system.

Within the Islamic intellectual tradition, there were divergent views on causality. The theologians of the Muʿtazilite school (8th–10th centuries) affirmed human free will and some level of natural causation – they held that God created substances with particular attributes, and those attributes could serve as causes for effects. For instance, fire has the attribute of burning; if God creates a situation where fire touches cotton, the cotton usually burns by the nature God gave to fire. However, the Muʿtazilites still maintained that God is omnipotent and could override natural causes with miracles when He wills. In contrast, the Ashʿarite theologians (notably al-Ashʿari and his followers) were uneasy with granting any real causal power to creatures, fearing it would diminish God’s absolute sovereignty. They developed a theory of acquisition (kasb) and occasionalism: God creates in the human the “power” to act at the moment of action, but God alone creates the actual effect.

By the 11th century, al-Ghazali – influenced by Ashʿarite thought – became the most famous proponent of occasionalism in the Islamic world. In his work Tahafut al-Falasifa (The Incoherence of the Philosophers), al-Ghazali attacked the Avicennian philosophers for claiming that causes necessitate their effects. He argued that if that were true, miracles would be impossible and God’s power would be limited. For al-Ghazali, only God is a true efficient cause; what we call “causes” in nature are merely occasions for God’s will to manifest an event. He gives the example of fire burning cotton: to common sense, fire causes burning. But al-Ghazali says the fire has no inherent power to burn at all – rather, each time fire contacts cotton, God directly creates the burning of the cotton. He is not denying the observed regularity (usually fire does precede burning); he is denying any necessary connection or intrinsic power in the fire itself. God has simply established a habit or customary sequence in nature, which we misinterpret as causality. At any moment, God could will a different outcome – like a miracle where a fire does not burn a prophet thrown into it. In al-Ghazali’s view, nature’s laws are descriptive, not prescriptive: they describe God’s usual practice, but do not bind Him.

This strict occasionalism was controversial. Ibn Rushd (Averroes), a 12th-century Aristotelian, criticized al-Ghazali strongly. He warned that if we deny all secondary causation, science and knowledge become impossible, since we rely on stable cause-effect relationships to learn how the world works. How could one have certainty that bread will nourish or medicine will heal, if “anything is possible” at any time except that God usually does the same thing? Al-Ghazali responded that one can have practical expectations of regularity, since God’s habits are consistent – but those habits themselves depend on His ongoing choice. Thus, reality is fundamentally contingent on God’s will at every moment, a concept sometimes called “continuous creation.” Al-Ghazali maintained that this does not undermine rational investigation; rather, it puts it in proper perspective. We can study how God usually orders phenomena, but we must not be deluded that the phenomena are operating autonomously. Occasionalism thus elevates God’s role from a mere first cause or remote architect to the immediate cause of every event, continually sustaining the existence and interaction of all things.

Quantum Nonlocality Meets Occasionalism

Quantum entanglement, as demonstrated by Aspect, Clauser, and Zeilinger, calls into question the classical idea of local causation – the notion that physical influences propagate outwards in space and time in a continuous chain. In an entangled pair of particles, measuring one seems to instantaneously “set” the state of the other, without any exchange of signals. From a classical perspective, this looks as if the second particle somehow “knew” the first was measured – which should be impossible if the only allowed cause is a normal signal traveling between them (limited by the speed of light). Bell’s theorem and the experimental violations of Bell’s inequality show that no story of local hidden variables can explain the observed correlations. In other words, the correlation has no local cause that we can pinpoint; it just happens when both are measured. This is a striking scientific result – and it sounds philosophically akin to al-Ghazali’s insistence that what we think of as “cause and effect” in nature is ultimately not due to any power in the objects themselves.

How might we compare these ideas? In occasionalism, when fire burns cotton, there is no physical necessity connecting the two – God directly causes the cotton to burn at the moment of contact. In entanglement, when photon A is measured and photon B’s state is instantly determined, there is no physical signal or force travelling from A to B – the link between them seems to transcend space. One could whimsically say it’s “as if God privately coordinated their outcomes.” In fact, some thinkers do view quantum nonlocality as providing room for a hidden global cause. While physics as a discipline avoids invoking God, it’s noteworthy that entanglement shows the universe behaving in one interconnected whole, rather than as a collection of isolated parts bumping into each other. Occasionalism similarly asserts that the universe’s events are unified by coming from one agency – God – rather than each object having independent causal efficacy.

Even the terminology overlaps: physicists speak of entangled particles forming one inseparable state until measured. Occasionalist theologians speak of the world being maintained by one will at every instant. Both perspectives reject a strict independence of parts. As Karen Harding observed, both the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and al-Ghazali’s metaphysics view objects as having “no inherent properties and no independent existence” apart from the act of measurement or divine causation. In quantum physics, an electron doesn’t have a definite position or spin until it is measured – before that, it’s described by a spread-out wavefunction, a set of potentials. In occasionalism, a piece of cotton doesn’t inherently have the power to burn (or not burn) – it only does what it does when God creates its action in that moment. Both frameworks replace autonomous, localized causation with something more enigmatic – an unseen order in which outcomes manifest when certain conditions are met, but not due to the conditions alone.

It’s important to stress that quantum mechanics does not prove theological occasionalism. What it shows is that nature at the quantum level defies classical causality. The “spooky action” of entanglement could be interpreted in purely scientific ways (e.g. that the universe has nonlocal hidden connections or a holistic state, as some interpretations like pilot-wave theory or many-worlds consider). However, for philosophers and theologians, quantum nonlocality resonates with the idea that the chain of physical causation is not the whole story. If measuring one photon instantly tells us about its distant partner, some deeper explanation is needed beyond classical locality. An occasionalist might suggest: just as God coordinates fire and burning cotton without a physical mechanism, perhaps God (or generally, a unitary underlying reality) coordinates entangled particles without a signal. In both cases, what we perceive as separate entities are linked by an invisible common cause.

God’s Continuous Sustenance and Quantum Indeterminacy

Al-Ghazali’s doctrine of God as the continuous sustainer of the universe means that not only did God create everything at the beginning, but at each moment, every object persists and every event occurs only because God is actively willing it. This “continuous creation” or sustenance is a core idea in occasionalism. It aligns with the Quranic name of God as “Rabb al-‘alamin,” often translated “Lord (Sustainer) of the worlds.” The implication is that without the divine presence, the world would cease to be from moment to moment. Reality is like a lightbulb that needs a steady current of electricity (divine power) to keep shining, rather than something that can glow on its own once switched on.

Quantum indeterminacy – the idea that outcomes of certain events are not fixed until observed – provides a potential physical echo of this theological concept. In classical physics, if you know the present state exactly, the future is determined; the universe could run on its own like a wound-up clock. But in quantum physics, even if you have total knowledge of a system’s wavefunction, you can only predict probabilities for different outcomes when you measure it. There is a fundamental uncertainty or openness about what will happen. For example, a radioactive atom might decay in the next hour or it might not – there is no hidden clock inside it (as far as we know) that says “decay at exactly 43 minutes.” Until it happens, the event is indeterminate. This is very different from classical thinking. Philosophers have noticed that if one were inclined, one could see in this indeterminacy an opportunity for divine input. Since the physics doesn’t dictate a single outcome, could it be that something outside physics “chooses” the outcome each time? This is speculative, but it has been discussed in the realm of theology-and-science dialogue. Some theologians (e.g. Robert John Russell, John Polkinghorne) have proposed that God might subtly influence which way a quantum event goes, without violating physical laws, since the laws only give probabilities. Such ideas are part of a broader discussion of “divine action in a quantum world.”

From an occasionalist perspective, one might go further to say: God doesn’t just nudge a few quantum events; God determines every event – effectively collapsing every wavefunction according to His will. In a strong form, we could dub this “quantum occasionalism.” In fact, the concept has been explicitly raised by scholars. As one research paper put it, “Indeterminism in quantum mechanics can be interpreted as a form of occasionalism.” The resemblance between modern physics and occasionalism has been noted by multiple authors. They draw parallels between the idea of God’s continuous creation and the way quantum theory suggests an ongoing “resolution” of indeterminate states into definite outcomes. If every quantum event – every time an electron’s position becomes real or a photon is detected – is an instance of “potential” becoming “actual,” one could philosophically imagine God as the one actualizing those potentials in conformity with the observed probabilities (or according to a divine pattern we interpret as probabilities).

Another link is the holistic nature of reality in both views. Occasionalism effectively says the universe is one giant system acted upon by God, rather than a bunch of independent systems. Certain interpretations of quantum mechanics, like ontological holism or wavefunction realism, similarly suggest that at root the universe might be a single, inseparable quantum state. The entanglement of particles across cosmic distances hints that space and separateness are secondary, and underlying reality might be “non-separable.” In theological terms, one might say creation is a unified whole held together by the One. Al-Ghazali’s insistence that no event is outside divine power dovetails with a picture of nature where everything is subtly interconnected and nothing happens in isolation.

It is worth noting, however, that quantum physicists typically do not invoke God in their explanations. The scientific process stops at describing the correlations and developing probabilistic rules. From that standpoint, quantum theory invites us to humility – recognizing that the classical certainties of causation have given way to mystery and probability. Al-Ghazali would appreciate this humility; he believed that relying purely on human reason to derive necessities in nature was hubris, since only God’s knowledge encompasses why things truly happen. In a sense, quantum physics has made science more humble about causality. We accept that at a fundamental level, we deal with probabilistic knowledge and cannot always say why this photon went left and the other went right – only that it fits a statistical pattern. Theologically, one might say this opens room for God’s sovereignty behind the statistics, much as al-Ghazali posited a divine will behind the habitual patterns of nature.

Modern Perspectives: Occasionalism Revisited in Light of Physics

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism was long regarded by many Western philosophers as a curious or even counter-intuitive doctrine. After the Enlightenment, thinkers like David Hume (who independently doubted necessary causation) and later Immanuel Kant engaged with occasionalist ideas, but mainstream science operated with an assumption of natural causality. In recent decades, however, interest in occasionalism has revived in niche discussions, partly due to the advent of quantum physics and other indeterministic or holistic scientific theories.

Within Islamic discourse, modern scholars approach occasionalism with nuance. Some see it as vindicated to a degree: the failure of strict determinism in physics and the discovery of “spooky” quantum connections make the universe seem less like a self-sufficient mechanism and more open to the Absolute. They point out that al-Ghazali’s insistence on contingency is compatible with a universe where chance and probability reign at the micro-level – a universe that needs a sustainer to choose outcomes or at least to maintain consistent order. Others caution that one should not rush to Islamize quantum theory; the physics doesn’t automatically confirm theological doctrines. Rather, it echoes them in suggestive ways. For example, the noted Pakistani physicist and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal in the 20th century praised al-Ghazali for emphasizing God’s presence, but he himself favored a view of God guiding evolution and natural law more subtly (a form of concurrentism rather than full occasionalism). The debate between seeing secondary causes as real (but dependent on God) versus seeing them as mere illusions sustained by God continues in modern Islamic theology. What quantum mechanics has done is make it intellectually respectable to question whether “cause and effect” is always a local material process – clearly, it isn’t, at least not at the quantum scale.

In the broader philosophical community, occasionalism also gets attention through comparisons of metaphysics and science. The concept of “quantum occasionalism” has been discussed by authors like Karen Harding (1993), Graham Harman (2016), and Simone Weir (2020). Harman, for instance, a proponent of Object-Oriented Ontology, used “new occasionalism” to describe how objects might interact only via a deeper reality (in his context not explicitly God, but it harkens back to occasionalist themes). Some Christian theologians draw parallels between occasionalism and the idea that God is the ground of being who lets creatures act – except at quantum junctures where He might directly steer outcomes. This is a kind of hybrid view: for macroscopic events they accept scientific causality, but they see God’s providence working at the indeterminate margins (a concept known as non-interventionist objective divine action in theology of science).

However, many philosophers of science would argue that we don’t need to invoke God to explain quantum phenomena – randomness may just be how nature is. The principle of parsimony leads most to not posit additional metaphysical entities if the theory works without them. Indeed, occasionalism is still a minority position in theology because it can be seen as making God responsible for everything (including bad events) and because it challenges the notion that creatures have any genuine agency – a notion precious to many religious and secular thinkers alike. A middle ground in classical theology is divine concurrence, which asserts that natural causes are real but God cooperates in every action. For example, when fire burns cotton, concurrence would say: the fire truly causes burning by virtue of the nature God has given it, and God concurrently wills the effect (sustaining the fire’s being and its causal power at that moment). This was the view of theologians like Thomas Aquinas. Occasionalism would strip away the fire’s causal role entirely. Now, does quantum physics favor concurrence or occasionalism? One might say it tilts a bit toward occasionalism only insofar as it underscores the insufficiency of a purely mechanical chain of causation. But one could also adapt concurrence: perhaps God concurs not just generally, but by inputting specific outcomes within the allowances of quantum laws.

From a faith perspective, the entanglement experiments of 2022 serve as a reminder that reality is profoundly interconnected and in some ways inscrutable. For a Muslim theologian reflecting on them, it might reinforce the Quranic message that God is “closer to you than your jugular vein” and “not a leaf falls but He knows it” – suggesting intimate involvement in the world. Al-Ghazali’s worldview, which puts God at the center of every event, suddenly doesn’t seem as irrational when even science tells us that particles a galaxy apart appear to coordinate without communication. It encourages a dialogue between modern physics and classical theology: not to crudely use one to prove the other, but to enrich our understanding of both. The strangeness of quantum mechanics can act as a bridge to discussing metaphysical questions in a fresh way. As one scholar noted, it’s “no coincidence” that the quantum revolution has led some to revisit the idea of “a sort of continuous creation of the world by God.”.

Conclusion

Quantum entanglement and the overthrow of local realism have highlighted that the universe does not always operate on the simple cause-effect principles imagined by classical physics. While scientists continue to interpret these phenomena within a scientific framework, the conceptual shockwaves extend into philosophy and theology. Al-Ghazali’s doctrine of occasionalism – the radical idea that only God is the true cause and sustainer of every event – finds a fascinating parallel in a quantum world where separate parts of reality appear eerily coordinated and outcomes are undetermined until observed. Both perspectives invite us to view reality as deeply unified and contingent. The Nobel-winning experiments of Aspect, Clauser, and Zeilinger show empirically that our world allows “spooky” connections, undermining the idea of self-sufficient local causation. Al-Ghazali provides a possible metaphysical explanation: a singular, unitary cause behind all apparent causes – in his terms, the will of God.

Of course, science and theology ask different questions. Physics won’t pronounce on God, and theology is not ultimately dependent on physics. Yet, the dialogue between them can be enriching. The occasionalist lens offers one way to interpret the quantum enigma: as a sign of a reality upheld at every instant by something beyond it. Even for those who do not embrace occasionalism, the comparison helps illuminate the limits of human understanding of causality. It underscores what the philosopher of science Ian Barbour called “critical realism” – that our scientific models are accurate but not exhaustive descriptions of an independently existing world, a world that might have more in store than billiard-ball causality. In an accessible sense, we might say quantum physics teaches us that mystery is woven into the fabric of the cosmos. Al-Ghazali would be unsurprised; he would perhaps smile and say this is exactly why one must trust in the constant grace of the Divine Reality underpinning all things.

In summary, quantum entanglement’s discovery that nature permits nonlocal, acausal-seeming connections provides a striking parallel to al-Ghazali’s occasionalist contention that natural causation is ultimately an illusion – a pattern sustained by God’s continuous action. Both point to a universe where what happens cannot be fully explained by the material pieces alone. The idea of God as the continuous sustainer of the universe finds an unexpected ally in modern physics’ most counterintuitive findings. This does not “prove” religious doctrine, but it beautifully illustrates how science and theology, each in its own language, can converge on a sense of wonder about a reality that is at once lawful and profoundly dependent on something deeper. Such integrated discussions, bridging entanglement and occasionalism, enrich our understanding by showing that mystery – whether we name it quantum nonlocality or divine will – lies at the heart of existence, inviting both awe and inquiry in equal measure.

Sources:

- Nobel Prize in Physics 2022 – Popular Information

- Nobel Prize in Physics 2022 – Press Release

- Scientific American – “Entangled particles and local realism”

- Al-Ghazali, Tahafut al-Falasifa (Discussion on Causality) – analysis by Adamson

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Causation in Islamic Thought”

- The Quran and Science Blog – “Nobel in Physics 2022 also goes to Al-Ghazali”

- Karen Harding (1993) – “Causality Then and Now: Al-Ghazali and Quantum Theory” (as cited in)

- Damiano Bondi (2024) – Religions Journal: “Humility and Realism in Quantum Physics and Metaphysics”

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – “Occasionalism” (European context)

- Averroes (Ibn Rushd) – Tahafut al-Tahafut (Incoherence of the Incoherence), critique of occasionalism

Leave a reply to Paul Davies, A Pantheist, Has Convinced Me of Al Ghazali – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply