Epigraph

What is the matter with you? Why will you not fear God’s majesty, when He has created you stage by stage? Have you ever wondered how God created seven heavens, one above the other, placed the moon as a light in them and the sun as a lamp, how God made you spring forth from the earth like a plant, how He will return you into it and then bring you out again, and how He has spread the Earth out for you to walk along its spacious paths? (Al Quran 71:13-20)

I call to witness the post-sunset glow, and the night and all that it envelops, and the moon when it becomes full, that you shall assuredly ascend from stage to stage. So what ails them that they believe not, and when the Quran is recited to them, they do not submit? (Al Quran 84:16-20)

Man, what has emboldened you against your Gracious Lord, who created you, then perfected you, then proportioned you right? He fashioned you in whatever form He pleased. (Al Quran 82:6-8)

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Opening up to the truth in evolution may lead us to a new and progressive understanding of the Glorious Quran.

For over a century, scientists have gathered molecular evidence that overwhelmingly confirms the theory of evolution. In the era of DNA sequencing and molecular biology, we can literally read the genetic code of different organisms and see the marks of their shared history. From DNA comparisons and protein structures to ancient genetic “fossils” within our genome, every level of molecular biology provides evidence that all life on Earth shares common ancestors. In this article, we’ll explore several key lines of molecular evidence in clear, everyday terms:

- Comparative Genomics: the genetic similarities between different species and what they tell us about common ancestry.

- Molecular Phylogenetics: how comparing DNA sequences allows us to build evolutionary family trees.

- Protein Homology: the striking resemblance of protein molecules across species.

- Endogenous Retroviruses (ERVs) & Junk DNA: “genetic scars” and leftover DNA that confirm shared descent.

- Mutation and Genetic Variation: how observable changes in DNA drive evolutionary change by natural selection.

- Molecular Fossils (Ancient DNA): actual DNA recovered from ancient remains that shows evolutionary transitions.

- Hox Genes & Developmental Biology: conserved developmental genes (like Hox genes) that reveal a common genetic toolkit across the animal kingdom.

Each section below will explain one of these concepts with examples, showing how modern molecular biology powerfully supports the fact of evolution. By the end, you’ll see why scientists say the evidence from DNA is even more conclusive than the fossil record in demonstrating how all organisms are related.

Comparative Genomics: Shared DNA Reflects Shared Ancestry

One of the most direct ways to see evolution is to compare the genomes (the complete DNA) of different living things. If two species evolved from a recent common ancestor, their DNA sequences should be very similar – much like two editions of the same book with only minor edits. On the other hand, species that are only distantly related (their last common ancestor lived eons ago) should have more DNA differences, as more time passed for mutations to accumulate. This is exactly what we observe. The more closely related two species are, the more alike their DNA is. In fact, DNA comparisons allow scientists to quantitatively measure how closely related organisms are.

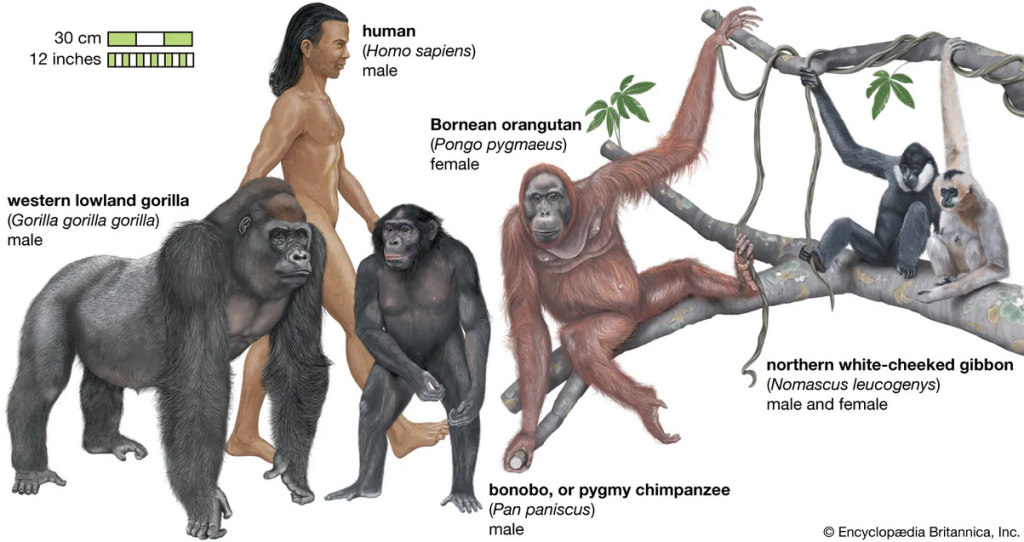

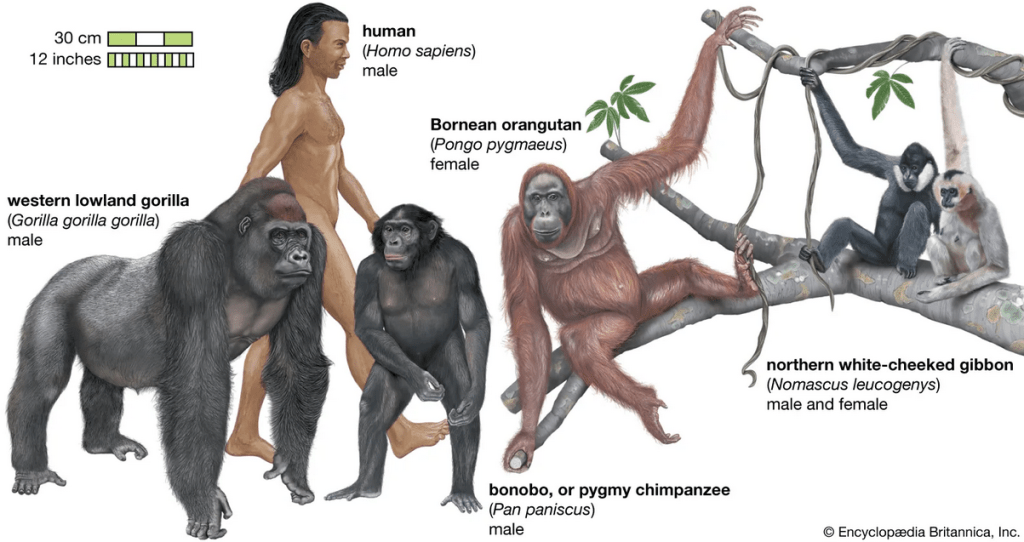

For example, consider the DNA of humans compared to some other animals:

- Humans and chimpanzees: Our closest living relatives, chimps (and their cousins bonobos), have DNA about 98–99% identical to human DNA. Only roughly a 1.2% difference in the DNA code separates us from chimps. This tiny difference is one reason chimps and humans have so many similar features.

- Humans and other mammals: We share about 85% of our DNA with a mouse (a fellow mammal). We even share about 90% with cats! Many genes in mice or cats have direct counterparts in our own genome.

- Humans and very distant organisms: Amazingly, even a fruit fly shares about 60% of its genes with humans, and even plants have many familiar genes – about 60% of human genes have an equivalent in the banana plant genome. In other words, over half of our genes are recognizably similar to genes in a banana.

Why would this be? The simplest explanation is that all these organisms inherited the core of their genomes from a far distant common ancestor. Basic cellular functions (like copying DNA or making energy) are so fundamental that the genes encoding them have been “conserved” (kept the same) over billions of years of evolution. A human cell, a mouse cell, a fly cell, and a plant cell all use many of the same molecular machinery – coded by the same or very similar genes – because they descend from an ancient single-celled ancestor that first evolved those genes. The strong similarity between humans and other great apes led Charles Darwin to predict we shared a recent ancestor; today, DNA comparisons have spectacularly confirmed that the human evolutionary tree is firmly embedded within the great apes

In fact, genetic data show humans, chimps, and bonobos form a cluster (more closely related to each other than to any other primates), and those three in turn share a slightly more distant ancestor with gorillas. This mirrors the classic “family tree” of primates that scientists had deduced from anatomy and fossils – but now supported by hard DNA evidence.

Another fascinating genomic evidence for common ancestry is how certain structural features of our chromosomes line up with those of other apes. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, whereas other great apes have 24 pairs. Why the difference? It turns out that human chromosome #2 is actually the product of an ancient end-to-end fusion of two smaller chromosomes that our ape relatives still have separately. Researchers discovered that human chromosome 2 has tell-tale extra DNA sequences in the middle of it: it contains unused centromere remnants and DNA sequences normally found only at chromosome ends (telomeres), but oddly located internally. This makes perfect sense if an ancestor of humans had two ape-like chromosomes that fused into one. Indeed, the banding and gene order of human chromosome 2 correspond almost exactly to two chimp chromosomes stuck together. The presence of those vestigial telomere and centromere sequences inside human chromosome 2 is like a molecular scar of the fusion event. It’s powerful evidence that humans and other apes once shared an ancestor with 24 chromosome pairs, and along the human line two of them joined – a prediction made by evolution and confirmed by genomic analysis. No other explanation predicts why a human chromosome would have such a peculiar structure.

In short, comparative genomics has fulfilled one of evolution’s key predictions: species that are closely related by evolution have genomes that are closely matched, down to unique DNA insertions and chromosomal structures. The more divergent the species, the more differences in their DNA – yet even those differences are consistent with the gradual change of an evolving lineage. Our genes and genomes are literally historical documents, recording the branching pattern of life’s family tree in their sequences.

Molecular Phylogenetics: Reconstructing the Family Tree from DNA

Comparative genomics doesn’t just tell us that species are related – it allows us to map out the family tree that connects all life. The field of molecular phylogenetics uses DNA and protein sequence data to deduce evolutionary relationships. The principle is straightforward: if genomes evolve by accumulating mutations over time, then the number of differences between the DNA sequences of two species indicates how long ago they shared a common ancestor. Close relatives have very few differences in their DNA, whereas distant relatives have many differences. By comparing many species’ DNA, scientists can cluster organisms by similarity and infer the branching order of their lineages – effectively building an evolutionary tree from molecular data.

Genetic analysis allows scientists to construct evolutionary trees. This diagram shows the primate family tree, based on DNA evidence, indicating how humans and other apes share recent common ancestors. For example, humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos branch from a common ancestor that lived ~6–8 million years ago, while all great apes share a more distant ancestor (~25 million years ago) that sets them apart from monkeys.

The power of molecular phylogenetics is that it provides an independent test of evolutionary relationships. Even if we had no fossils or knowledge of anatomy, DNA alone could reveal the pattern of descent. For instance, DNA comparisons long ago confirmed that whales are most closely related to mammals like hippos and deer (not to fish), even before transitional fossils were found to support that relationship. Similarly, genetic trees have clarified relationships that were murky from anatomy alone – such as the exact branching order of bird groups and the connections between extinct human species and modern humans. In case after case, the “family tree” calculated from molecular data aligns with what we’ve gathered from the fossil record and other evidence, boosting our confidence that both are reflecting the same historical reality.

Importantly, molecular phylogenetics also gives a way to estimate when species diverged. By using genes that mutate at a relatively steady rate as a “molecular clock,” scientists can date evolutionary events. For example, by measuring the small DNA differences between humans and chimps and knowing the typical mutation rate, researchers estimated our last common ancestor lived roughly 6–7 million years ago – which matches the ages of the earliest hominin fossils. These techniques make evolution measurable on the molecular scale. The evolutionary tree of life, once only sketched from comparative anatomy, can now be drawn in detail using genetic data. The fact that we can independently derive the same tree from completely different datasets (genes vs. anatomy vs. fossils) is a testament to the robustness of evolutionary theory. Different lines of evidence converge on the same story: a tree of life with branching lineages, quantifiable in DNA.

Protein Homology: The Same Molecules in All Forms of Life

DNA is not the only molecular evidence of evolution – the proteins encoded by that DNA also tell the tale of common ancestry. Proteins are the working molecules of cells (for example, enzymes and structural proteins), and when we compare essential proteins across different species, we often find remarkable similarities. Biologists call these “homologous proteins” – proteins in different organisms that have similar amino acid sequences or 3D structures because they were inherited from a common ancestor.

One classic example is the protein cytochrome c, which is involved in cellular respiration (energy production in the mitochondria). Cytochrome c is found in virtually all eukaryotic organisms, from yeasts to humans, because it’s vital for life. When scientists sequenced the amino acids of cytochrome c from a variety of species, they noticed a pattern: the sequence is identical or nearly identical in very closely related species, and gradually more different in more distant species, in proportion to evolutionary distance. For instance, the cytochrome c of humans and chimpanzees (and other primates) is exactly the same – no differences in the 104 amino acids. Compared to a horse’s cytochrome c, the human version has 5 amino acids that differ. Compared to a chicken’s version, about 6 differences are present. A frog’s cytochrome c differs by 8 amino acids from the human one, and a shark’s by 13 amino acids . In general, the number of amino acid differences in this protein corresponds to how far apart the species are on the evolutionary tree (with monkeys differing by only 1 amino acid, and non-mammals differing by more). Such detailed molecular comparisons serve as an independent check on evolutionary relationships – even at the level of single molecules, we see the signature of descent with modification.

Another striking case is the hormone insulin. Human insulin is a protein of 51 amino acids, and when we compare it to insulin from other animals, it’s nearly unchanged. Bovine (cow) insulin differs from human insulin by only 3 amino acids, and pig insulin by just 1 amino acid. In fact, pig insulin works so similarly to ours that for many years diabetic patients were treated with pig insulin to regulate their blood sugar – a pig’s insulin could function in a human body because the molecule is essentially the same. Even some fish insulin is similar enough to human insulin to have effects in our bodies. The strong conservation of insulin’s sequence across vertebrates (and even beyond) indicates that this protein has been doing the same job in organisms for a very long time, inherited from a common ancestor of all those animals. When a protein is crucial to basic biology, evolution tends to retain its structure – any major change might be lethal, so only small tweaks accumulate over time. Thus, we find that many proteins are like molecular “living fossils”, remaining recognizable in vastly different creatures.

It’s not only the sequences but also the three-dimensional structures of proteins that often carry an evolutionary stamp. Proteins that perform similar functions in different species frequently fold into very similar shapes, even if their DNA sequences have diverged. For example, the hemoglobin protein that carries oxygen in our blood has a very similar structure in all mammals (and birds), with only minor sequence variations between species. Drug companies exploit this fact – they can study a human protein’s structure by using an easier-to-obtain version from rats or pigs because the homology (similarity due to shared ancestry) is so high. Overall, protein homology provides molecular testimony of common ancestry: if evolution were not true, there is no reason two different organisms would use nearly identical complex proteins for the same task – yet they do, everywhere we look. The simplest explanation is that they inherited those protein blueprints from a common ancestor and gradual evolution modified them to the needs of each species.

Endogenous Retroviruses and “Junk DNA”: Genetic Remnants of Evolution

Not all evidence for evolution comes from functional genes and proteins. Some of the most compelling clues come from the portions of the genome that don’t code for proteins at all – sometimes called “junk DNA” (though not all of it is truly junk). In particular, genomes contain lots of repetitive, inactive sequences that are essentially molecular fossils: they are left-over remnants of things like ancient viruses or broken genes. One category of these is endogenous retroviruses (ERVs). These are DNA sequences in our genome that originated from retroviruses inserting their genetic material into the germline (sperm or egg cells) of an ancestor. If a virus infects a sperm or egg cell and embeds its DNA, it can sometimes get passed on to the next generation as a permanent part of the genome – that virus has effectively become endogenous. Over millions of years, such viral inserts accumulate (most losing their ability to cause disease), and today about 8% of the human genome consists of virus-derived DNA from ancient retroviral infections. In other words, a big chunk of what was once considered “junk” DNA in our genome is actually the scar tissue of old viruses that infected our ancestors.

So how do ERVs demonstrate evolution? The key is to realize that the chance of a retrovirus inserting itself at exactly the same location in the genomes of two unrelated species is astronomically small. It would be like two people randomly flipping open a massive book and inserting the same unique string of letters at the exact same page and line by pure coincidence. Thus, if we find identical viral DNA inserts at the same genomic positions in different species, the most logical explanation is that they inherited this insert from a common ancestor (the original infection happened before the species split, so both descendant lineages carry it). And in fact, this is exactly what we see: humans and other primates share many of the same ERV sequences in the same chromosomal locations, conclusively indicating common descent. For example, researchers have identified dozens of instances of endogenous retrovirus insertions that humans, chimpanzees, and other apes all share at corresponding sites – insertions that are absent in more distantly related mammals. The odds of this pattern happening by independent insertions are effectively zero. As one genetics expert explained, “when you see hundreds of thousands of retroviral insertions at the same place in two different genomes, you know they had to be inherited from a common ancestor, because there is no plausible way that many independent insertions would happen at the exact same base [position].” The shared ERVs are like molecular fingerprints linking species to a common forebear.

ERVs are a dramatic example, but there are other types of non-functional or semi-functional DNA elements that also serve as evolutionary evidence. Pseudogenes, for instance, are genes that have been inactivated by mutations. Often, a pseudogene in one species has the same disabling mutation as the corresponding pseudogene in a related species – meaning it likely became defunct in their common ancestor. A famous case is the gene for making vitamin C: most mammals can synthesize their own vitamin C, but primates (including humans) cannot, because we all have the same broken gene (called GULO) that no longer works. The human GULO gene is a fragmentary pseudogene – and chimpanzees and gorillas have an almost identical broken version, with matching mutations that prevent it from functioning. It’s highly unlikely that three different species would acquire the same disabling mutations by chance; instead, it’s clear evidence that this gene was already broken in a common ancestor (so all descendants inherited the defect). Our inability to make vitamin C is an evolutionary legacy of our fruit-eating primate ancestors who didn’t need the gene, and it mutated away. Dozens of such shared pseudogenes have been documented among related species, reinforcing their evolutionary relationships.

Scientists no longer like to use the term “junk DNA” too broadly, because we’re learning that some of these once-mysterious sequences have minor functions. But whether functional or not, the patterns of these DNA elements across species make sense only in light of evolution. The human genome is a patchwork quilt of not just genes, but also ancient viral inserts, duplicated sequences, and mutated genes – and by comparing with other genomes, we can trace how each piece got there. The fact that the very same genomic oddities appear in multiple species is like finding the same typo in several photocopies of a document – it strongly implies they’re copies of the same original source. ERVs and shared pseudogenes provide that kind of smoking-gun evidence for common ancestry. They are genetic markers carried silently in our DNA, patiently waiting millions of years to tell their story – a story of evolution.

Mutation and Genetic Variation: Evolution in Real Time

We’ve been discussing how genomes record ancient evolutionary events. But we can also observe evolution happening on the molecular level in real time, through mutations and genetic variation in populations. A mutation is simply a change in the DNA sequence – it could be as small as a single letter (base) change, or as large as a deletion or duplication of many genes. Mutations occur naturally all the time as DNA is replicated; most are harmless or neutral, a few are harmful, and occasionally one might improve an organism’s chances of survival or reproduction. These mutations are the raw material for evolution – without them, there would be no new traits for natural selection to act upon. As scientists often say, “mutations are the raw material of evolution.” They create the heritable differences between individuals that Darwin realized were necessary for natural selection to produce change. In modern terms, evolution can be defined as a change in the genetic makeup of a population over generations – and mutations are what introduce those genetic changes in the first place.

We have directly measured and observed genetic mutation and evolution in action. For example, biologists have performed long-term experiments with bacteria (which reproduce rapidly) and documented how random mutations that arise can spread through the population when they confer an advantage. In one famous experiment, E. coli bacteria evolved the ability to eat a new food (citrate) after tens of thousands of generations – a feat that was traced to specific DNA mutations that researchers pinpointed. In nature, we also see plenty of real-world evolution driven by mutations. A striking case is the development of resistance to antibiotics or pesticides. When a new antibiotic drug is widely used, at first it wipes out almost all targeted bacteria – but usually a few microbes happen to have a mutation that makes them a bit less vulnerable. Those few survive and multiply, and soon the entire bacterial population becomes resistant to the drug. This can happen very fast. In fact, scientists have found that even within a few years, pests or germs can evolve resistance thanks to rare mutations spreading under selection pressure. For instance, in a large population of weeds sprayed with a herbicide, by chance a tiny fraction of plants may carry a mutation that helps them survive the poison. Those mutant weeds are the ones left to reproduce, so the next generation is full of herbicide-resistant weeds. This is evolution happening on a human time scale – essentially, natural selection filtering out the susceptible genes and enriching the resistant genes. The same process has been observed in insects gaining resistance to insecticides, and even in viruses like HIV evolving resistance to antiviral medications.

The fact that we directly see mutations giving rise to new adaptations is a strong affirmation of the evolutionary process. At the DNA level, we can sequence the genomes of organisms before and after an experimental evolution trial (or before and after developing drug resistance) and literally spot the new mutations that appeared. We’ve gone from Darwin’s era – when variation was observed but its molecular basis unknown – to an era where we can pinpoint “this single-letter change in the DNA made this bacterium resistant to penicillin.” This demonstrates that genetic variation + selection = evolutionary change. Over longer time frames and in larger, sexual populations, the same principles apply: mutations create variation in traits, and the environment/natural selection decides which variants get passed on more. Given enough generations, these small genetic changes can accumulate to big differences – ultimately generating the diversity of life forms we see. In short, molecular genetics has validated the mechanism of evolution on the smallest scale, showing that mutations (random changes in DNA) fuel adaptation and divergence. It’s evolution caught in the act, down to the letter of the genetic code.

Molecular Fossils: Ancient DNA as Direct Evidence of Evolutionary Transitions

For a long time, fossils (the preserved remains of ancient organisms) were the only window into evolutionary history. Now, thanks to advances in technology, scientists can sometimes extract and analyze actual DNA from fossilized or preserved remains – in effect, retrieving genetic information from organisms that died tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years ago. These ancient DNA sequences are like “molecular fossils,” and they provide direct evidence of evolutionary change and lineage splits. Perhaps the best-known example is the DNA sequencing of Neanderthals and other archaic humans. Neanderthals are an extinct hominid species that lived alongside early Homo sapiens. In 2010, scientists successfully sequenced the Neanderthal genome from >40,000-year-old bones. The results were eye-opening: Neanderthal DNA was found to be 99.7% identical to modern human DNA, only slightly more divergent than any two present-day humans are from each other. (For context, humans and chimps are about 98.8% identical, so humans and Neanderthals at 99.7% are extremely close kin.) This provided dramatic confirmation that Neanderthals were our close evolutionary cousins – closer than any other creature on Earth. In fact, the genetic data showed that our lineages split roughly 400,000 years ago, matching what paleoanthropologists suspected from fossils. Moreover, portions of the Neanderthal genome are more similar to those of people in Europe and Asia than to those of people in Africa, leading to the discovery that early modern humans interbred with Neanderthals. As a result, about 1–2% of the DNA in today’s non-African humans is inherited from Neanderthal ancestors. This finding – a literal genetic contribution from an extinct species – is direct evidence of evolution as a branching and blending process, and it could only have been revealed by molecular analysis.

And Neanderthals aren’t the only case. Scientists have sequenced DNA from other extinct forms like the Denisovans (another ancient hominin), the woolly mammoth (to compare with living elephants), an ancient horse from ~700,000 years ago, and even fragments of DNA from much older species in permafrost cores. Each time, the ancient DNA slots into an evolutionary tree exactly where expected. For example, mammoth DNA shows that mammoths were slightly more distant relatives to Asian elephants than African elephants are – confirming the relationships inferred from anatomy. Ancient plant and animal DNA also lets us see evolutionary change unfolding: a sequence from a fossil polar bear showed how recently they diverged from brown bears, and DNA from ancient maize (corn) samples illustrates how humans domesticated and changed that plant over time. These are instances of transitional forms captured in genetic code. Instead of guessing how one species gave rise to another, we can sometimes directly sample the DNA of an intermediate population and see the mixture of traits.

What’s especially powerful about ancient DNA is that it connects genotype to phenotype in the past. For instance, researchers have identified mutations in Neanderthal DNA that likely affected their skin and hair, giving hints about Neanderthal appearance. We can also detect signs of natural selection in ancient genomes by seeing which gene variants became more common over time. Ancient DNA has even allowed scientists to resurrect molecular functions of long-lost proteins – for example, reconstructing ancestral hormone receptors to study how their specificity evolved over hundreds of millions of years. These kinds of studies form a field sometimes called “paleogenomics.” They enable tests of evolutionary hypotheses that were purely speculative before. The successful sequencing of ancient genomes stands as one of the most compelling achievements in modern biology, effectively watching evolution in retrospective, and it invariably reinforces the evolutionary connections among species. If evolution were not true, it’s hard to imagine why the DNA from a fossilized bone would neatly fit the pattern of a family tree linking it with living species. Yet that is exactly what happens, time and again.

Hox Genes and Development: A Shared Genetic Toolkit for Body Plans

One of the most fascinating molecular evidences for evolution comes from evolutionary developmental biology (“evo-devo”), particularly the study of Hox genes. Hox genes are a group of master regulator genes that act like architects during embryonic development, telling cells what to become and where. They are responsible for the basic body layout (head-to-tail organization) in animals. What’s astonishing is that very different animals – from fruit flies to mice to humans – all possess Hox genes, and these genes are incredibly similar across these species. In fact, many Hox genes in a fruit fly have clear counterparts in a human, and if you swap them, often they can still function. This points to a shared evolutionary origin of the entire genetic program for building bodies.

A fruit fly with a homeotic mutation (the Ultrabithorax Hox gene disabled) grows a second pair of wings in place of the small balancing organs normally on its rear segment. The normal fruit fly (left) has one pair of large wings and two tiny halteres (balancers) behind them; the mutant fly (right) has two pairs of full wings. This dramatic change occurs from a single gene tweak, showing how Hox genes direct body plans. Importantly, the presence and function of Hox genes are the same in all animals – the genes that pattern a fly’s body are closely similar to those that pattern a human’s body.

Hox genes contain a special DNA sequence called the “homeobox,” and they arose early in animal evolution. They have been highly conserved (kept with little change) for over half a billion years. As a result, the role Hox genes play is fundamentally the same in every animal: they produce proteins that are transcription factors (DNA switches) which turn other genes on and off, thereby mapping out the body’s regions during development. Whether you’re a tiny insect or a large mammal, Hox genes are active in the embryo, instructing a cell on whether it’s in the head region, the middle, or the tail end of the organism. This is a beautiful example of a deep homology – a shared ancestral genetic toolkit. It also explains why, for example, both flies and humans have a segmented body plan (head, thorax/abdomen for the fly; head, thorax, abdomen in humans if you consider vertebrae and limb regions) arranged by similar genetic signals. As evolutionary biologist Sean Carroll famously said, “worms, flies, and humans are built using variations on the same ancient genetic themes.”

The conservation is so strong that scientists have done cross-species experiments: In a now-classic experiment, researchers inserted a Hox gene from a mouse into a fruit fly that was missing its version of that gene – and the mouse gene was able to direct normal development in the fly!

Despite the immense evolutionary distance between flies and mice, the basic language of that developmental gene was understood by the fly’s cells. Likewise, the gene that controls eye development (called Pax6) is so conserved that a squid’s version can trigger eye formation in a fly, and a mouse’s version can do so as well. These experiments dramatically demonstrate that the genetic “instructions” for building bodies and body parts originated in a common ancestor and have been repurposed and modified over evolutionary time, but not fundamentally rewritten. A human and a fly parted ways in evolution over 600 million years ago, yet we still share these master genes.

The example of the four-winged fruit fly (pictured above) is also illustrative. Normally, fruit flies have one pair of wings and a pair of halteres (small knob-like organs) as balance sensors. A mutation in a Hox gene (Ubx) can cause the halteres to turn into an extra pair of wings. This is a big change, but it’s not the invention of a new wing out of thin air – it’s actually the mis-expression of an existing program (the second segment’s wing program is repeated in the third segment). This shows how relatively simple genetic changes can yield large anatomical changes, which is how evolutionary transitions in body plans can occur. In the fossil record we see, for instance, insects in the Paleozoic era with multiple pairs of wings, and evolutionary reduction to fewer wing pairs later – changes in Hox gene regulation are a plausible mechanism.

The key takeaway is that the unity of developmental genes across animal phyla is overwhelming evidence of common descent. It’s improbable in the extreme that such specific and complex genes (organized in clusters, expressed in sequence along the body axis) would independently arise in each lineage. Instead, the best explanation is that the last common ancestor of all bilaterian animals (creatures with a head-tail axis, probably around 600 million years ago) already had a set of Hox genes, and all its descendants – from flies to fish to us – inherited that set. Evolution then tweaks the usage of these genes to create the diversity of forms. But underneath, the genetic toolkit remains recognizable. As one research article put it, Hox proteins are a “deeply conserved” group of body-patterning factors, using the same mechanism in all animals. This again highlights a theme in molecular evidence: fundamental biological systems (genetic codes, core metabolic pathways, key developmental genes) are universal or widely shared, which is exactly what we expect if life evolved from common ancestors rather than appearing independently.

Conclusion: The Molecules Speak – Evolution Is Unmistakable

From the DNA in our chromosomes to the proteins that execute life’s processes, the molecular world is filled with evidence for evolution. Comparative genomics shows a continuum of genetic similarity that only evolutionary relationships can explain. Molecular phylogenetics reconstructs the same family tree of life that other methods indicate, confirming Darwin’s theory with quantitative precision. The homology of proteins across species reveals that life has innovated by modifying existing parts, not by creating wholly new ones from scratch for each species. The remnants of viral infections and broken genes in our “junk DNA” act as genomic fossils, pointing to specific common ancestors and events in evolutionary history. We can watch mutations introduce new genetic variation and see natural selection spread those changes through populations – evolution happening on a small scale that, given time, leads to the large-scale differences among species. And the ancient DNA pulled from long-dead organisms, as well as the conserved developmental genes like Hox, allow us to time-travel and directly witness evolution’s handiwork, confirming lineages and ancestral traits.

What’s truly elegant is how all these diverse lines of evidence converge. They each offer insight from a different angle, but they paint the same picture: a picture of relatedness, divergence, and descent with modification. No longer is evolution inferred only from bones and morphology; we now read it in the four-letter alphabet of DNA and the thirty-letter alphabet of amino acids. As one NIH report stated about the Neanderthal genome, “the genomic calculations showed good correlation with the fossil record” – in other words, the DNA evidence independently matches what we expect if evolution is true. It is hard to imagine a more powerful scientific vindication.

Crucially, this molecular evidence is accessible and intuitive. One doesn’t need to be a geneticist to grasp that if two books have whole paragraphs of identical text, they probably weren’t written independently – one likely descended from the other or from a common source. Genomes work the same way. Our genome and a chimp’s genome share too many specific similarities for it to be coincidence; common ancestry is the logical explanation. And the deeper we delve – examining endogenous retroviruses, shared pseudogenes, or conserved protein sequences – the more detailed the story becomes, down to individual mutations that our distant forebears carried. In a sense, every cell of every organism contains the narrative of evolution, written in code. Molecular biology has provided us the key to read that narrative, and it overwhelmingly confirms what Darwin and others hypothesized: all life is related. Evolution is not just an abstract theory; it’s inscribed in our DNA. The molecules speak, and they say: Evolution is true.

Leave a reply to Both Agreeing and Disagreeing With Javed Ahmed Ghamidi – The Glorious Quran and Science Cancel reply