Epigraph

“True dreams are one of the forty-sixth part of prophethood.” Prophet Muhammad

Written and collected by Zia H Shah MD, Chief Editor of the Muslim Times

Human history is rich with examples of groundbreaking ideas that emerged not in the laboratory or library, but in the mysterious theater of dreams. Beyond mere flights of fancy, dreams and subconscious “aha” moments have contributed to serious advances in science, mathematics, philosophy, literature, and the arts. Pioneering scientists have solved problems after a good night’s sleep, writers have woken with stories that changed literature, and composers have literally heard melodies in their dreams. This article explores how the subconscious mind – through dreams or relaxed reverie – has sparked creative insights in these fields, excluding overtly mystical or religious visions. Instead, we focus on secular dream inspirations: the real-life cases where sleeping brains solved waking problems, and what that means for human knowledge and creativity.

Science and Mathematics: Discoveries Dreamed into Being

Throughout the history of science, there are startling cases of eureka moments arising from dreams or subconscious visions. Puzzling over complex problems by day, scientists and mathematicians have sometimes found that a solution presented itself after their minds wandered or slept. Modern psychology suggests this is no coincidence – sleep and the unconscious mind can forge novel connections between ideas. As sleep researcher Matthew Walker explains, “Sleep seems to stimulate your mind to make non-obvious connections… This is the basis of creativity – connecting ideas, events and memories that wouldn’t normally fit together.”

In the REM stage of sleep (when vivid dreams occur), our brains are highly active in reorganizing information, which is why we sometimes wake up with new insights. Here are a few famous examples of scientific and mathematical insights that literally came in dreams:

- Albert Einstein’s Relativity: As a teenager, Albert Einstein had a vivid dream that he was sledding down a steep hill at night, going faster and faster until he nearly reached the speed of light. In the dream, the stars above him changed appearance as his speed approached light-speed, “being refracted into colors I had never seen before,” he later recalled. Waking from this exhilarating vision, Einstein felt “awe” and sensed “he was looking at the most important meaning in his life.”. He would later cite this dream as an early inspiration for his theory of Special Relativity, saying his “entire scientific career was a meditation on this dream.” It was not a mystical prophecy but Einstein’s subconscious mind grappling with physics. The dream’s image of racing light beams helped the young Einstein conceptualize what it would mean to travel at light-speed, seeding ideas that blossomed years later into relativity theory.

- Friedrich Kekulé and the Benzene Ring: The German chemist August Kekulé struggled in the 1860s to determine the structure of the benzene molecule, a mystery confounding chemists at the time. The breakthrough came to him in a reverie (some say a dream) of a snake seizing its own tail – the ancient ouroboros symbol. Kekulé realized the image implied a ring structure. He famously announced that he “discovered the ring shape of the benzene molecule after having a reverie or day-dream of a snake eating its own tail.” This intuitive vision gave Kekulé the idea that benzene’s six carbon atoms form a closed ring, solving the chemical puzzle. His dreamlike insight into cyclic structures revolutionized organic chemistry.

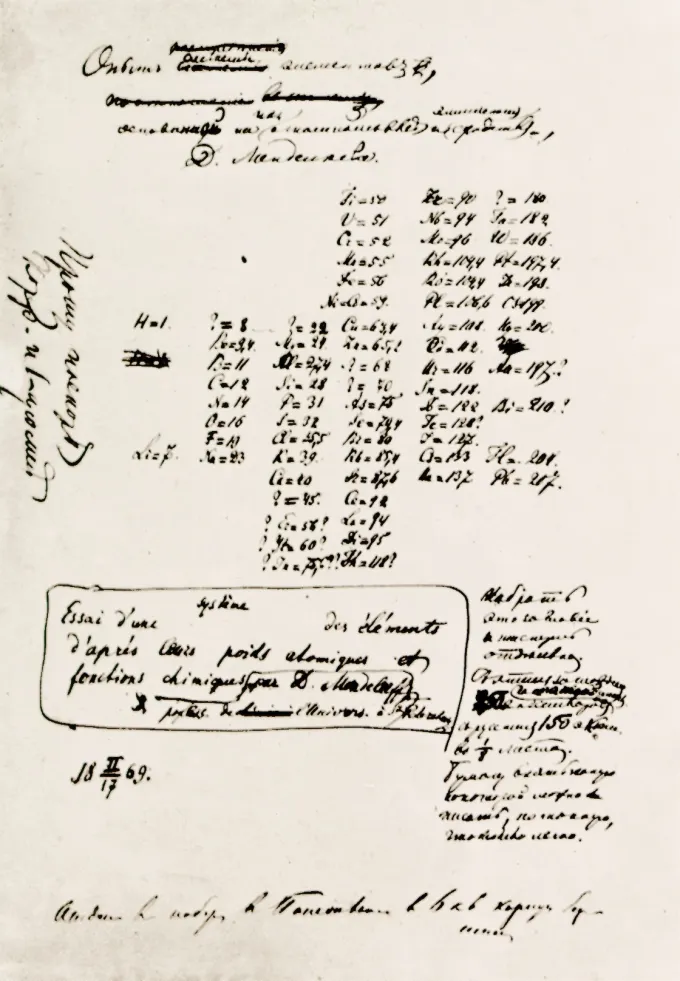

- Dmitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table: In 1869, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev had been laboring to organize the 56 known elements into a logical table, without success. Exhausted, he fell asleep at his desk – and dreamed the complete periodic table. “I saw in a dream a table where all the elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper,” Mendeleev recounted. His dream revealed the correct periodic arrangement of elements by atomic weight and properties. Upon waking he scribbled down the table (needing only one minor correction). That dream-born table was the basis of the periodic table we use today – a cornerstone of chemistry that Mendeleev likely wouldn’t have cracked as quickly without his unconscious mind’s nocturnal help.

Mendeleev’s 1869 handwritten draft of the periodic table, reportedly inspired by his dream of the elements falling into place.

- Srinivasa Ramanujan’s Mathematical Visions: The brilliant Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920) often said that his profound formulas were gifted to him in dreams. A deeply spiritual man, Ramanujan believed that the Hindu goddess Namagiri would show him complex mathematical formulas in his sleep – sometimes unfurling before him as scrolls of equations or writing on a red screen of blood. “While asleep, I had an unusual experience…Suddenly a hand began to write on the [blood-red] screen… a number of elliptic integrals. They stuck to my mind. As soon as I woke up, I committed them to writing,” Ramanujan described of one such dream. Though he attributed these revelations to divine influence, one can also view it as his subconscious genius at work. By day Ramanujan was intensely engaged with equations, and by night his brain continued solving problems, presenting him with novel theta function formulas and continued fraction results that he would verify upon waking. Many of the dream-born theorems Ramanujan recorded turned out to be true and highly original. His case exemplifies how the sleeping mind can marshal deep intuition to yield mathematical breakthroughs that conscious thought alone might not produce.

These are just a few of the best-known instances. There are other remarkable examples: Niels Bohr dreamed of electrons spinning around an atom’s nucleus like planets orbiting a sun – a vision that inspired his model of the atom’s structure. Otto Loewi, in 1921, dreamed of an experiment proving how nerves transmit signals chemically; waking up, he carried it out and discovered neurotransmitters, earning a Nobel Prize. In each story, the person had immersed themselves in a problem, hit a wall consciously, and then the subconscious mind continued working in the background. The dream or half-dream provided a creative insight or metaphor that solved the puzzle. As one science writer put it, sleeping, the brain “synthesizes and organizes recent observations… conceptualizes a problem in a more holistic way… and can provide the basis for the solution.” In short, science has occasionally advanced because a researcher quite literally “dreamed up” the answer.

Philosophy and Intellectual Thought: Dreamy Origins of Big Ideas

Philosophers are in the business of pondering reality, knowledge, and existence – and even they have not been immune to insights from dreams. While philosophical breakthroughs more often come from reasoned thought, there are notable cases where dreams influenced a thinker’s direction or illustrated a profound idea:

- René Descartes’ Three Dreams: The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) described a life-changing night of dreams in November 1619 that shaped his entire intellectual mission. “On the night of 10 November 1619, he had three dreams that seemed to provide him with a mission in life,” according to one biographical account. The dreams were strange and symbolic (he interpreted one as an angel or “divine spirit” whispering to him), but Descartes took from them the message that he should “set out to reform all knowledge.” He felt called to unify mathematics, science, and philosophy – which led him to develop analytic geometry and his method of systematic doubt in philosophy. Descartes later wrote that these dream-visions revealed to him “a new philosophy” and showed “all truths [are] linked to one another.” While he may have seen a divine hand in the dreams, the content essentially galvanized Descartes’ rationalist project and the famous conclusion “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”). His case shows a dream igniting an epistemological quest – using intuition to set the agenda for logical inquiry.

- Zhuangzi’s Butterfly Dream: Over two millennia earlier, a Chinese philosopher posed a profound question about reality based on a dream. Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu, 4th century BC), a Taoist thinker, wrote of a dream in which he was a carefree butterfly. Upon waking as himself again, Zhuangzi wondered: “Now I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man.” This simple butterfly dream metaphor carries deep philosophical implications in epistemology and metaphysics: it challenges our ability to distinguish reality from illusion. Zhuangzi’s dream thought-experiment anticipates questions of consciousness and reality that philosophers still discuss (e.g. Descartes’ Meditations considers whether life could be a dream or deception by an “evil demon”). In Zhuangzi’s case, an actual dream experience directly inspired a famous parable about the fluid boundary between dream and waking – urging humility about what we claim as “real.”

- Dreams as Thought Experiments: Beyond these two, dreams have occasionally influenced other intellectuals. Historically, dream arguments have been used by philosophers to illustrate skepticism (Descartes, as mentioned, used the possibility that he might be dreaming to doubt the reliability of senses). The Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant spoke metaphorically of being “awoken from dogmatic slumber” by reading David Hume – using a dream metaphor to describe a philosophical awakening. In a more psychological vein, Carl Jung (1875–1961) derived some of his theories about archetypes and the collective unconscious from intense dream imagery (though his work bridges psychology and mysticism). While these are not direct discoveries from dreams in the way scientific cases are, they underscore that dreams have long been food for thought in philosophy. They can reveal to a thinker, in a visceral way, the perplexing nature of reality, self, and knowledge, spurring new lines of reasoning about mind and world.

In sum, dreams have provided philosophical insight both as inspirational episodes that set thinkers on new paths (as with Descartes) and as illustrative anecdotes encapsulating abstract ideas (as with Zhuangzi’s butterfly). They remind us that behind great rational systems there are often very human moments of intuition, imagination – and occasionally, dreamlike wonder.

Poetry and Literature: The Dream as Creative Spark

Literature and poetry thrive on imagination, so it’s no surprise that many writers have drawn direct inspiration from dreams and nightmares. The line between dreams and storytelling is often thin; a compelling dream can feel like a ready-made poem or narrative delivered to the author’s mind. Some iconic works in English literature, in fact, owe their existence to the author’s dream-life:

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan: One of the most famous dream-inspired poems is Coleridge’s Kubla Khan. As Coleridge himself explained in a preface, the poem came to him in an opium-influenced sleep in 1797. He had been reading about the exotic palace of Kubla Khan in Xanadu when he drifted into a deep dream, in which he “perceived the entire course of the poem.” Upon awakening, Coleridge began furiously writing down the “vision in a dream” of “Kubla Khan”, but was unfortunately interrupted by a visitor (“a person on business from Porlock”) partway through. This interruption caused him to forget the rest of the lines he had composed in his dream. The fragment he managed to record – 54 lines describing the mythical pleasure-dome of Xanadu – was later published in 1816, exactly as he remembered from the dream. Kubla Khan’s vivid imagery and surreal atmosphere make it a quintessential dream-poem. Coleridge’s experience illustrates how dreams can deliver creative content in a flash; he effectively transcribed a subconscious vision into art. The poem’s subtitle “A Vision in a Dream” and its unfinished state are testaments to its dream-born nature.

- Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: In 1816, 18-year-old Mary Shelley famously conceived the idea for her novel Frankenstein from a nightmare. She was staying at Lake Geneva with Percy Shelley and Lord Byron during a stormy summer, and the group challenged each other to write ghost stories. Mary felt pressure to come up with a scary tale, and one night she had a “waking dream” (as she later described) that provided the spark. In this vision, she saw “a pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together,” and then beholding the horrifying result of his experiment – “the hideous phantasm of a man” coming to life with dull yellow eyes. She awoke trembling, realizing she had found her story. The next morning Mary Shelley began writing Frankenstein, starting with the memorable line “It was on a dreary night of November…” which describes Dr. Frankenstein’s act of animating the creature. Thus, a nightmare directly morphed into one of the first science-fiction novels and a gothic classic. Shelley later noted that the novel was merely a “transcript” of the “grim terrors” of her waking dream. The enduring power of Frankenstein – its exploration of creation and responsibility – began with that one potent dream image.

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde: Another 19th-century classic literally came in a nightmare. Robert Louis Stevenson had been searching for a storyline about dual personality when he dreamt a scenario that thrilled and terrified him. In 1885, Stevenson’s wife Fanny recounted being awoken by his cries of horror during the night – she roused him, fearing a nightmare, only to have him complain, “Why did you wake me? I was dreaming a fine bogey tale.” He had been dreaming the scene of Dr. Jekyll’s first transformation into the evil Mr. Hyde, and was angry to have lost the climax! Stevenson immediately set to work turning this “fine bogey tale” from his dream into a written story. In just a few days, he drafted Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. He later confirmed in an essay that the plot resolution “was made plain to me in a dream”, crediting his subconscious for providing the key scenes. The novella, published 1886, became famous for its depiction of split personality and the duality of human nature. Had Stevenson not dreamt that visceral transformation scene, the story of Jekyll and Hyde might never have fully materialized.

Many other writers have taken inspiration from dreams. For example, Edgar Allan Poe often drew on his feverish dreams and nightmares for story ideas; H.P. Lovecraft said certain of his horror tales came directly from dreams. More recently, Stephen King noted that the idea for his novel Misery struck him in a dream, and Stephanie Meyer’s blockbuster Twilight was inspired by a dream image as well (the author dreamt of a human girl and a vampire boy in a meadow, which became a scene in the book). In poetry, too, the boundary between dream and creation is porous – Poe’s poem “A Dream Within a Dream” explores that very theme, and dreams have provided motifs for countless poets.

What’s notable is how immediate and intact some of these dream inspirations are: Coleridge experienced his poem fully formed (only external interruption stopped it); Shelley effectively watched a horror scene like a movie in her mind; Stevenson literally saw his story play out while asleep. These examples highlight the creative potential of the dreaming mind, which can serve as an imaginative collaborator. Of course, turning a dream into a coherent literary work still requires skill and effort from the author when awake – but the initial spark, the mood, the central image or concept, arrived as a gift from the subconscious. Dreams, it seems, can be nature’s way of workshopping a story or poem in the theatre of the mind before it’s set to paper.

Music and the Arts: Composing and Creating in Sleep

Musicians and artists have also reported that some of their most inspired work came to them in dreams or moments of semi-conscious creativity. It’s one thing to intellectually compose a melody or design – it’s another when a fully formed tune simply pops into your head from nowhere, often at 3 AM. Yet this happens more often than one might think, even to the greats. Here are a few striking cases where dreams influenced music and art:

- Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday”: The Beatles’ legendary ballad “Yesterday” (1965) literally came to Paul McCartney in a dream. McCartney has explained that one morning he woke up with a beautiful melody in his head – so complete that he was sure he must be remembering an existing song. “I woke up with a lovely tune in my head,” McCartney said, and he rushed to a piano by his bed to work out the chords before it faded. The melody was indeed original, a gift from his dreaming mind. For weeks, McCartney went around asking people if they’d heard that tune before, convinced he must have unconsciously plagiarized it. Only when no one claimed it did he accept that it was new and finish the song (with placeholder lyrics jokingly titled “Scrambled Eggs” until he found the real words). That dream-born song, “Yesterday,” became one of the most recorded and beloved songs in pop music history. Its gentle tune and melancholic lyrics certainly feel like they bubbled up from deep in the soul. McCartney’s experience shows the subconscious mind’s prowess in music – composing a complete melody without any awake effort. His only job upon waking was to catch it and write it down.

- Keith Richards’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” Riff: In another rock music anecdote, Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards dreamed the famous guitar riff of “Satisfaction.” In May 1965, Richards awoke from sleep with a three-note riff in his head (and the phrase “I can’t get no satisfaction”). He grabbed a bedside cassette recorder, played the riff once, mumbled a lyric line, and fell back asleep. The next morning, he discovered he’d recorded a rough version of what would become the Stones’ biggest hit. “I had no idea I’d written it,” Richards later said, noting that after the riff there were forty minutes of him snoring on the tape! The song, born from that hazy early-morning moment, features one of the most iconic riffs in rock history. If Richards hadn’t woken and hit “record” in that instant, the riff might have been lost. This story underscores how ephemeral yet crucial these dream inspirations can be in music – the brain can compose in sleep, but the artist must act quickly to capture the tune upon waking.

- Classical Composers and Dream Music: Dream inspiration is not limited to pop/rock – classical composers have a long history of it too. A dramatic example comes from the 18th century: Giuseppe Tartini dreamed that the Devil came and played violin at the foot of his bed. In this 1713 dream (a kind of infernal jam session), Tartini was astonished as Satan played the most beautiful, complex piece of music he had ever heard. He awoke and frantically tried to scribble down the music from memory. The result was the “Devil’s Trill Sonata”, a fiendishly difficult violin sonata. Tartini admitted that while the sonata he wrote was the best he ever composed, it was still a pale shadow of what he’d heard in the dream! Nonetheless, Devil’s Trill Sonata stands as a masterpiece of the violin repertoire – all thanks to a vivid dream. Similarly, Mozart was known to “hear” complete passages of music in his mind (though in his case during wakeful daydreaming) and often said compositions would come to him fully formed as if by intuition. Beethoven reportedly kept a notebook by his bed for musical ideas that struck in the night. In the realm of visual art, Salvador Dalí famously cultivated hypnagogic half-dream states to generate the surreal images for his paintings – he would nap briefly and catch the odd visions that surfaced in his relaxed mind, calling this method “slumber with a key.” In all these cases, the artists tapped into the subconscious creative wellspring.

Modern neuroscience suggests why music, in particular, might come in dreams: musical memory and creativity are often deeply ingrained, and during REM sleep the brain can blend memory, emotion, and random neural firing into new melodies. Many songwriters have described waking up with a melody or hearing music in dreams; it’s as if the brain continues “composing” off-line. The challenge is translating that ephemeral gift into waking reality. McCartney succeeded; so did composers like Tartini. Countless others have felt a brilliant idea slip away with the alarm clock. Those who capture their dream inspirations contribute enormously to culture – giving us songs and compositions that feel otherworldly in their genius.

The Subconscious Mind and the Creative Process: Implications of Dream Inspiration

What do these examples tell us about human creativity and knowledge? First, they highlight the remarkable power of the subconscious mind. Dreams (and related states like daydreaming or hypnagogic half-sleep) allow the brain to approach problems and ideas in a looser, more associative way than conscious, focused thought. This often leads to “non-obvious connections” – the very definition of creativity. While awake, we might be limited by logic, habit, or mental blocks; in dreams, the mind roams freely through memories and concepts, occasionally stumbling on gold. Psychologists describe this phenomenon in terms of incubation and insight: when you “sleep on” a problem, you literally give your brain time to subconsciously work through it. No wonder the old adage advises that when faced with a tough dilemma, get a good night’s sleep – by morning, the solution might present itself.

Moreover, these stories debunk the notion that creativity is only the product of conscious genius or supernatural intervention. There is nothing mystical (in the paranormal sense) about dream inspiration. It’s our own mind at work – but on a level that feels almost magical because it’s hidden from our direct view. Albert Einstein processing the thought-experiment of riding a light beam, Mendeleev’s brain sorting chemical properties into a table, Mary Shelley’s imagination conjuring a gothic scene – all of that thinking was likely percolating subconsciously due to intense conscious engagement during the day. When the solution or idea finally surfaces in a dream, it feels like an external revelation, yet it was generated by the person’s own cognitive resources. As one sleep researcher noted, “during sleep we also begin making new connections with the information we collect… our brains allow the default mode network to do its thing: make new, unexpected connections.” REM sleep, in particular, is linked to creative insight – studies have found that people are more likely to solve a puzzle after REM sleep than after non-REM sleep or quiet rest, because REM fosters abstract associative thinking.

The broader implication is that creativity and problem-solving are not always linear processes. Allowing the mind to relax – whether through literal sleep or through activities that engage the “default mode network” (like taking a walk, meditating, or yes, dreaming) – can yield breakthroughs as important as those achieved by grinding away awake. Many Nobel prizes, artistic masterpieces, and profound ideas might never have materialized if their creators hadn’t benefited from a crucial dream or intuitive flash. It suggests that cultivating our subconscious (by getting adequate sleep, paying attention to dreams, or practicing techniques like dream journaling) could be a practical tool for innovation. In fact, some modern artists and scientists actively try to “incubate” dreams about specific problems – a technique known as dream incubation, following in the footsteps of people like Kekulé or Loewi.

Culturally, the tales of dream-born creations also remind us of the mysterious, almost poetic aspect of discovery. They add a humanizing narrative to achievements in logic or art. Knowing that Frankenstein was sparked by a nightmare or that the idea of the periodic table literally came in a dream makes these achievements feel more accessible and marvelously serendipitous. It’s as if the universe of ideas has a will of its own, whispering to receptive minds in the quiet of the night. In truth, it’s our own minds whispering to ourselves, but the effect is much the same.

In conclusion, from Einstein’s theory of relativity to McCartney’s “Yesterday,” human knowledge and culture have been enriched by those willing to listen to their dreams. These accounts are not about effortless genius – the dreamers still had to do the hard work of verification, elaboration, and execution when awake – but they show that breakthroughs can come in moments of surrender rather than effort. Science, philosophy, literature, and music have all been advanced by a partnership between the conscious and unconscious parts of our mind. The “creative spark” might ignite at 2 AM when a solution presents itself in a dream, or when a melody drifts into one’s head upon waking. By embracing the contributions of our dreaming brains, we embrace the full spectrum of human creativity. After all, as the poet Edgar Allan Poe wrote, “Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.” The heroes of our stories did both – they dreamed by night, and then harnessed those visions in the light of day, leaving a lasting legacy on human thought.

Leave a comment