Presented by Zia H Shah MD as is from Gemini 3, please confirm details for yourself

Abstract

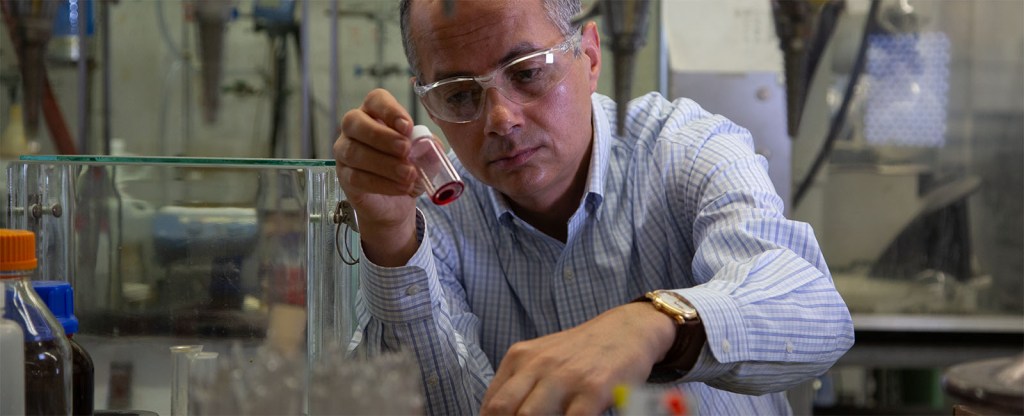

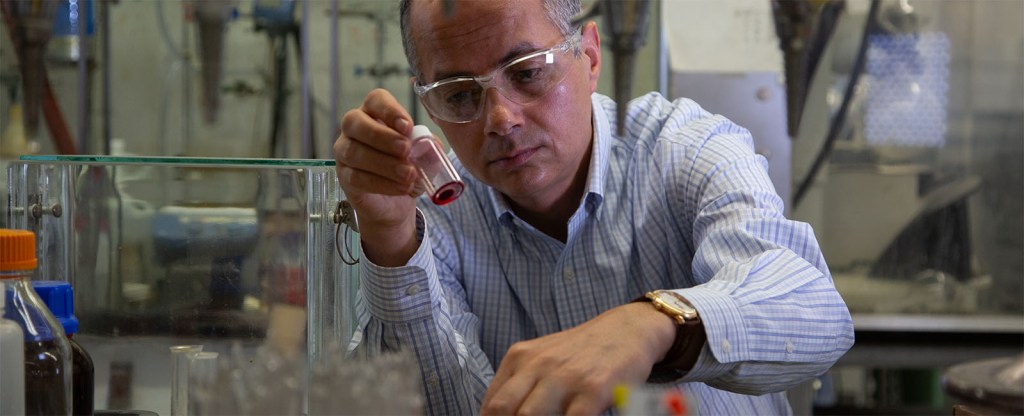

The career of Omar M. Yaghi represents a singular narrative in the annals of modern chemistry, tracing a trajectory from the stark material scarcity of a Jordanian refugee camp to the receipt of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This report provides an exhaustive biographical analysis of Yaghi’s life and scientific contributions, beginning with his early childhood in Amman as the son of Palestinian refugees and his formative education shaped by environmental stressors such as water scarcity. It examines his academic migration to the United States at age fifteen, his rigorous doctoral training under Walter Klemperer at the University of Illinois, and his postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard under Richard Holm. Central to this narrative is Yaghi’s invention of reticular chemistry—a field defined by the rational assembly of molecular building blocks into extended crystalline frameworks via strong bonds. The report details the landmark discoveries of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), and Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs), alongside their revolutionary applications in atmospheric water harvesting, carbon sequestration, and clean energy storage. Finally, it reflects on Yaghi’s dual role as a global mentor through the Berkeley Global Science Institute and his 2025 Nobel Prize recognition, which stands as a watershed moment for scientific achievement in the Arab world.

The Foundations of Displacement: Childhood in Amman

The life of Omar Mwannes Yaghi began amidst the geopolitical and humanitarian turbulence of the mid-twentieth century Middle East. Born on February 9, 1965, in Amman, Jordan, Yaghi was the child of Palestinian refugees who had been displaced from their ancestral village of Al-Masmiyya during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Al-Masmiyya, situated between Jaffa and Jerusalem, was lost during the Nakba, forcing his family to seek sanctuary in Jordan, where they eventually settled in a refugee camp environment. This heritage of displacement and the resultant socioeconomic marginalization formed the backdrop of Yaghi’s early developmental years.

Yaghi’s childhood home in Amman was characterized by extreme austerity and high population density. The family, which eventually included ten or twelve children, lived in a single shared room. This modest dwelling functioned as a multi-purpose space, lacking basic infrastructure such as electricity and reliable running water. To support the family, Yaghi’s father operated a butcher shop and raised cattle within the same confined living space. The presence of livestock in the domestic environment was not merely a logistical challenge but a constant reminder of the family’s proximity to their means of survival.

The environmental conditions of Jordan, particularly the perennial issue of water scarcity, exerted a profound influence on Yaghi’s psyche and future research interests. In Amman, water was a commodity of extreme stress; the municipal supply was often only available for a few hours every one to two weeks. As a young boy, Yaghi was tasked with the critical responsibility of managing the family’s water stores. He spent hours queuing at public taps, acutely aware that the volume captured during these brief windows dictated the family’s health and hygiene for the subsequent fortnight. This early exposure to resource fragility instilled in him a lifelong appreciation for the stresses caused by water scarcity, which he later identified as a primary driver for his scientific focus on atmospheric water harvesting.

Summary of Early Biographical Markers

| Parameter | Detail |

| Date of Birth | February 9, 1965 |

| Place of Birth | Amman, Jordan |

| Family Origins | Al-Masmiyya, Palestine |

| Socioeconomic Status | Refugee; modest upbringing in a one-room home |

| Domestic Amenities | No electricity, no running water, shared space with cattle |

| Parental Education | Father: 6th grade; Mother: Illiterate |

Despite their lack of formal education, Yaghi’s parents were unwavering in their support of their children’s intellectual advancement. His father, recognizing the limitations of the refugee camp environment, consistently urged Omar to think independently and use education as a vehicle for transcendence. His mother, though unable to read or write, provided a nurturing environment that allowed Yaghi’s independent personality to develop through the observation of the world.

The Latent Scientist: Formative Intellectual Awakening

Yaghi’s induction into the world of science was neither formal nor conventional. At the age of ten, he discovered a sanctuary in the school library, a facility that was frequently locked and required clandestine entry. It was during one of these unauthorized visits that he encountered a book containing molecular illustrations—specifically ball-and-stick models representing chemical structures. At the time, he did not possess the vocabulary to identify these drawings as molecules; however, he was profoundly moved by their symmetry, complexity, and aesthetic beauty. He later reflected that this visual encounter with the “hidden world” of chemistry served as his calling, establishing an early desire to become a chemist even before he understood the mathematical or physical principles underpinning the discipline.

By the time he reached mid-adolescence, the discrepancy between his intellectual potential and the opportunities available in Jordan became increasingly apparent to his father. In 1980, at the age of fifteen, his father insisted that Omar emigrate to the United States to pursue his education. This decision was both a sacrifice and a strategic investment in Omar’s future, requiring the young teenager to navigate the complexities of international migration, language acquisition, and financial self-sufficiency entirely on his own.

The American Frontier: Troy and the Path through Albany

Upon arriving in Troy, New York, in 1980, Yaghi faced immediate challenges related to cultural assimilation and linguistic barriers. With a very limited grasp of the English language, he initially struggled to communicate effectively, yet he remained focused on his educational objectives. He enrolled at Hudson Valley Community College (HVCC), where he began a curriculum focused on English, mathematics, and science. To fund his education and living expenses, he worked various service-sector jobs, including bagging groceries and mopping floors. These early years in the United States were characterized by a relentless work ethic, as he balanced the rigors of community college with the physical demands of manual labor.

Yaghi’s time at HVCC was brief but foundational. In 1983, he earned an Associate of Science degree in Mathematics and Science, a milestone that facilitated his transfer to the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany. It was at Albany that Yaghi’s fascination with molecular drawings evolved into a sophisticated understanding of chemical reactivity and synthesis. He flourished in the laboratory environment, finding that the practical application of chemistry provided a sense of clarity and purpose that lecture halls alone could not offer. A defining moment occurred when he observed the crystallization of benzoic acid; the transformation of a liquid into a beautiful, structured solid crystal was a sensory experience that cemented his devotion to the field.

He graduated cum laude from the University at Albany in 1985 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry. His performance at Albany not only demonstrated his academic caliber but also positioned him to enter one of the premier graduate programs in the United States.

The Dialectics of Discovery: Graduate Studies at UIUC

In the fall of 1985, Yaghi began his graduate studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), a period that would fundamentally reshape his scientific methodology. He joined the research group of Professor Walter G. Klemperer, an inorganic chemist known for his technical rigor and demanding standards.

Klemperer’s mentorship was characterized by a philosophical commitment to the idea that “science starts with doubt”. He pushed Yaghi to move beyond the replication of existing knowledge and instead focus on the creation of entirely new chemical species and paradigms. Under Klemperer, Yaghi learned the importance of rigorous data analysis and the necessity of questioning every experimental outcome until it could be verified with absolute certainty.

Doctoral Research and Inorganic Cavitands

Yaghi’s doctoral research centered on the synthesis of complex polyoxometalate clusters, specifically polyoxovanadates. This work required an exceptional degree of patience and technical skill; one particular deprotonation reaction involving H3V10O283− took an entire year of failed experiments before a successful synthesis was achieved. This perseverance eventually led to the discovery of bowl-shaped inorganic molecules that could act as hosts for guest molecules like acetonitrile. These “inorganic cavitands” represented a significant advancement in host-guest chemistry, demonstrating that discrete inorganic clusters could possess well-defined cavities for molecular recognition.

Despite his success, Yaghi found the traditional approach to creating extended materials—often described as “building them up to tear them apart”—to be intellectually unsatisfactory. He noticed that while organic chemists could design complex molecules with atomic-level precision, materials scientists often relied on trial-and-error, high-temperature methods that lacked rational design rules. It was during this period at UIUC that he began to conceive of a new approach: constructing extended 2D and 3D frameworks using molecular building blocks held together by strong bonds.

In 1990, Yaghi completed his PhD, receiving the Theron Standish Piper Award for an outstanding doctoral thesis in inorganic chemistry. His graduation from UIUC marked the transition from a student of chemistry to a potential pioneer of a new field.

Milestone Education Summary

| Institution | Degree | Year | Academic Honors |

| Hudson Valley Community College | Associate of Science | 1983 | |

| University at Albany, SUNY | Bachelor of Science | 1985 | Cum Laude |

| University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign | PhD in Inorganic Chemistry | 1990 | Theron Standish Piper Award |

| Harvard University | Postdoctoral Fellowship | 1992 | NSF Postdoctoral Fellow |

Synthesizing Paradigms: The Harvard Postdoctoral Fellowship

In 1990, Yaghi accepted a National Science Foundation (NSF) postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard University, working under the guidance of Richard H. Holm. If Klemperer had instilled in him the value of doubt, Holm provided the essential counterbalance: “Science is an exercise in optimism”.

At Harvard, Yaghi was exposed to a different chemical philosophy. While his graduate training had focused on a “bottom-up” approach—assembling clusters from molecular precursors—Holm’s group often employed a “top-down” strategy, synthesizing extended solids and then breaking them down to excise specific clusters that were otherwise unattainable. The tension between these two perspectives was intellectually formative for Yaghi. He realized that the future of materials chemistry lay in the ability to design extended structures with the same level of precision that organic chemists applied to discrete molecules.

During his time at Harvard, Yaghi grappled with the decision to pursue a career in industry or academia. Given his family’s refugee status and the financial pressures of supporting his parents back in Jordan, a lucrative industrial position was a practical necessity. However, his drive for scientific exploration and the desire to mentor others ultimately outweighed financial considerations. He chose academia, securing an assistant professor position at Arizona State University in 1992.

The Reticular Revolution: Arizona State University (1992–1998)

Yaghi’s independent career began in Tempe, Arizona, where he faced significant skepticism from the established scientific community. At the time, the synthesis of extended porous materials was dominated by zeolites and porous carbons, which were typically made using high-temperature, trial-and-error methods. Many senior chemists believed it was impossible to link molecular building blocks with strong bonds to form stable, crystalline, and highly porous 3D structures at mild temperatures.

Undeterred, Yaghi and his graduate students at the Goldwater Center at Arizona State embarked on a quest to upend these limitations. He began collaborating with Michael O’Keeffe, a professor whose expertise in crystallography and topology complemented Yaghi’s synthetic ingenuity. Together, they began to formalize the rules of what Yaghi would later term “reticular chemistry”—the art of stitching molecular building blocks into extended structures using strong chemical bonds.

The Invention of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

The initial efforts focused on hybridizing inorganic metal ions with organic linkers. Previous attempts at creating such hybrids—often called coordination polymers—had resulted in frail, disordered, or non-porous materials that collapsed upon the removal of the solvent. Yaghi’s breakthrough came from the introduction of “Secondary Building Units” (SBUs): rigid metal-carboxylate clusters that served as stable structural nodes.

In 1995, Yaghi’s team successfully synthesized and crystallized a metal-organic structure where metal ions were joined by charged carboxylate linkers via strong bonds. In a landmark article in Nature, he coined the term “Metal-Organic Framework” (MOF). This work demonstrated that MOFs could maintain their structure even when empty, providing a platform for “permanent porosity” that far exceeded that of existing zeolites.

The Era of Permanent Porosity: University of Michigan (1999–2006)

In 1999, Yaghi moved to the University of Michigan as the Robert W. Parry Professor of Chemistry. It was in Ann Arbor that reticular chemistry achieved its first truly global sensation: the discovery of MOF-5.

MOF-5 was composed of zinc oxide clusters linked by terephthalate organic molecules. When Yaghi published the results in 1999, the material displayed a surface area of nearly 3,000 m2/g, a figure that was three times higher than the most porous carbon and six times higher than the most porous zeolite known at the time. The internal surface area of just a few grams of MOF-5 was equivalent to the area of a football field.

Industrial Validation and the BASF Partnership

The sheer magnitude of MOF-5’s porosity led to disbelief among established researchers. Ulrich Mueller, a scientist at the German chemical company BASF, initially suspected that the published surface area was a misprint. However, upon reproducing the work, BASF confirmed the results and even achieved slightly higher surface areas. This led to a productive, long-term collaboration between Yaghi and BASF, which demonstrated that MOFs could be scaled from milligrams in the lab to multi-ton production for industrial use in gas storage and separation.

Comparison of Porous Material Surface Areas (circa 2000)

| Material Type | Representative Example | Surface Area (m2/g) | Discovery Source |

| Zeolite | Zeolite Y | ≈600–900 | Traditional |

| Porous Carbon | Activated Carbon | ≈1,000 | Traditional |

| Early MOF | MOF-2 | ≈250 | Yaghi (1995) |

| Record-Breaker | MOF-5 | ≈2,900–3,300 | Yaghi (1999) |

Organic Expansion: UCLA and the Invention of COFs

Yaghi’s tenure at UCLA (2007–2012), where he served as the Christopher S. Foote Professor of Chemistry, saw a further diversification of the reticular chemistry portfolio. While MOFs combined metal nodes with organic linkers, Yaghi sought to create purely organic crystalline frameworks.

In 2005, he achieved the first synthesis of Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs). Unlike MOFs, COFs are held together by strong covalent bonds between light elements such as boron, carbon, and oxygen. This resulted in highly stable, low-density materials with extremely high thermal stability and the added ability to store charged ions, making them ideal for supercapacitors and batteries.

He also developed Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs), which expanded the capabilities of zeolite catalysts in industry by incorporating the chemical versatility of organic linkers with the robust topology of traditional zeolites. During his time at UCLA, his team continued to break records, producing MOF-200 in 2010, which set a new high-water mark for surface area and gas storage capacity.

The Berkeley Vision: Global Science and Sustainability

In 2012, Yaghi moved to the University of California, Berkeley, as the James and Neeltje Tretter Professor of Chemistry. At Berkeley, Yaghi’s work took on a more explicitly humanitarian and global focus, bridging the gap between basic chemical research and pressing environmental challenges.

Atmospheric Water Harvesting (AWH)

Drawing directly from his childhood experiences of water scarcity in Amman, Yaghi pioneered the use of MOFs for atmospheric water harvesting. He realized that certain MOFs, such as MOF-303, could be engineered to “seek and trap” water molecules from the air even at low humidity levels (below 20%) typical of desert environments.

In 2018 and 2019, Yaghi’s team conducted field tests in Tempe, Arizona, and the Mojave Desert, demonstrating that a kilogram-scale MOF device could extract a liter of pure drinking water per day using only ambient sunlight as an energy source. This technology offered a pathway to “water independence,” allowing communities in arid regions to generate their own water supply without relying on centralized, often inaccessible infrastructure.

The Berkeley Global Science Institute (BGSI)

Recognizing that talent is distributed globally but opportunity is not, Yaghi founded the Berkeley Global Science Institute (BGSI) in 2014. The mission of the BGSI is to build research centers in developing countries—including Vietnam, Malaysia, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico—to provide local scholars with the mentorship and resources to solve regional problems using reticular chemistry. Through this “global science” model, Yaghi has mentored hundreds of researchers, empowering them to contribute to the global scientific community while addressing local needs in energy and environment.

Digital Materials and AI Integration

In 2022, Yaghi became the scientific director of the Bakar Institute of Digital Materials for the Planet (BIDMaP) at UC Berkeley. This institute focuses on using Artificial Intelligence and machine learning to accelerate the discovery of new MOFs and COFs. By integrating AI, Yaghi’s group can screen thousands of potential material candidates in a fraction of the time required for traditional synthesis, targeting specific properties for carbon capture and clean energy.

Technical Applications of Reticular Frameworks

| Application | Material Class | Mechanism | Environmental Impact |

| Water Harvesting | MOF-303, MOF-300 | Adsorption of H2O from low humidity | Decentralized water for arid regions |

| Carbon Capture | COF-999, MOF-177 | Selective binding of CO2 from flue gas/air | Mitigation of industrial emissions |

| Hydrogen Storage | MOF-5, MOF-200 | Compact physisorption of H2 gas | Enabling zero-emission fuel tank technology |

| Catalysis | ZIFs, MTV-MOFs | Enzymatic-like reactions in pores | Efficient chemical processing; energy conversion |

The Zenith of Recognition: The 2025 Nobel Prize

The multi-decade development of reticular chemistry reached its historical peak on October 8, 2025, when the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Omar M. Yaghi. He shared the honor with Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson “for the development of metal-organic frameworks”.

The citation acknowledged their independent work in creating a “new form of molecular architecture”. While Robson had proposed the theoretical framework in 1989 and Kitagawa had explored gas uptake in flexible frameworks, Yaghi was credited with making MOFs architecturally robust and permanently porous, thereby transforming the field from a theoretical curiosity into a practical solution for global sustainability.

Yaghi received the news during a stopover in Brussels. Surrounded by busy travelers, he spent an hour on the phone with the Nobel Committee, reflecting on the “astonishment” of the moment. The win was celebrated across multiple nations: in the United States, as a testament to the “American dream”; in Jordan, as the first Jordanian-born laureate; and in Saudi Arabia, where he had been granted citizenship in 2021, as the first Saudi national to win a scientific Nobel.

Major Awards and Honors Timeline

- 2007: Newcomb Cleveland Prize (AAAS)

- 2015: King Faisal International Prize & Mustafa Prize

- 2017: Albert Einstein World Award of Science

- 2018: Wolf Prize in Chemistry (with Fujita Makoto)

- 2019: Gregori Aminoff Prize (Royal Swedish Academy)

- 2021: VinFuture Prize (Vietnam)

- 2024: Tang Prize in Sustainable Development

- 2024: Great Arab Minds Award in Natural Sciences

- 2025: Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Thematic Epilogue: The Resilience of the Designed Mind

The biography of Omar Yaghi is more than a chronicle of academic appointments and chemical syntheses; it is a narrative of resilience, precision, and the philosophical transformation of scarcity into abundance. Yaghi’s early life was defined by the profound absence of material stability—a one-room home, a lack of running water, and the status of a refugee. Yet, it was this very environment of lack that catalyzed his pursuit of “beautiful things” and the rational design of matter.

Thematically, Yaghi’s work embodies the bridge between the “hidden world” of molecules and the tangible realities of human survival. By creating materials with the highest surface areas known to date, he has effectively “unrolled” the football fields of the molecular world to capture the gases and vapors that dictate our planet’s climate and health. His invention of reticular chemistry reflects a shift in the human relationship with matter—from passive users of natural resources to active architects of the atomic realm, capable of “stitching” together a sustainable future with the precision of a master weaver.

Perhaps his most enduring legacy lies in his commitment to the “global science” model. Having experienced firsthand the power of science as an “equalizing force,” Yaghi has spent his career ensuring that the tools of reticular chemistry are placed in the hands of those who need them most. From the desert air of Arizona to the research centers of Vietnam and Jordan, he has demonstrated that scientific innovation is not the exclusive domain of the privileged but the rightful inheritance of any mind possessed of curiosity and persistence. As he stood in a busy airport to receive the call from Stockholm, the journey from the refugee camp in Amman was complete, yet for the architect of porosity, the exploration of the “new rooms for chemistry” has only just begun.

Leave a comment