Epigraph

فَلَمْ تَقْتُلُوهُمْ وَلَٰكِنَّ اللَّهَ قَتَلَهُمْ ۚ وَمَا رَمَيْتَ إِذْ رَمَيْتَ وَلَٰكِنَّ اللَّهَ رَمَىٰ ۚ وَلِيُبْلِيَ الْمُؤْمِنِينَ مِنْهُ بَلَاءً حَسَنًا ۚ إِنَّ اللَّهَ سَمِيعٌ عَلِيمٌ

Al Quran 8:17

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

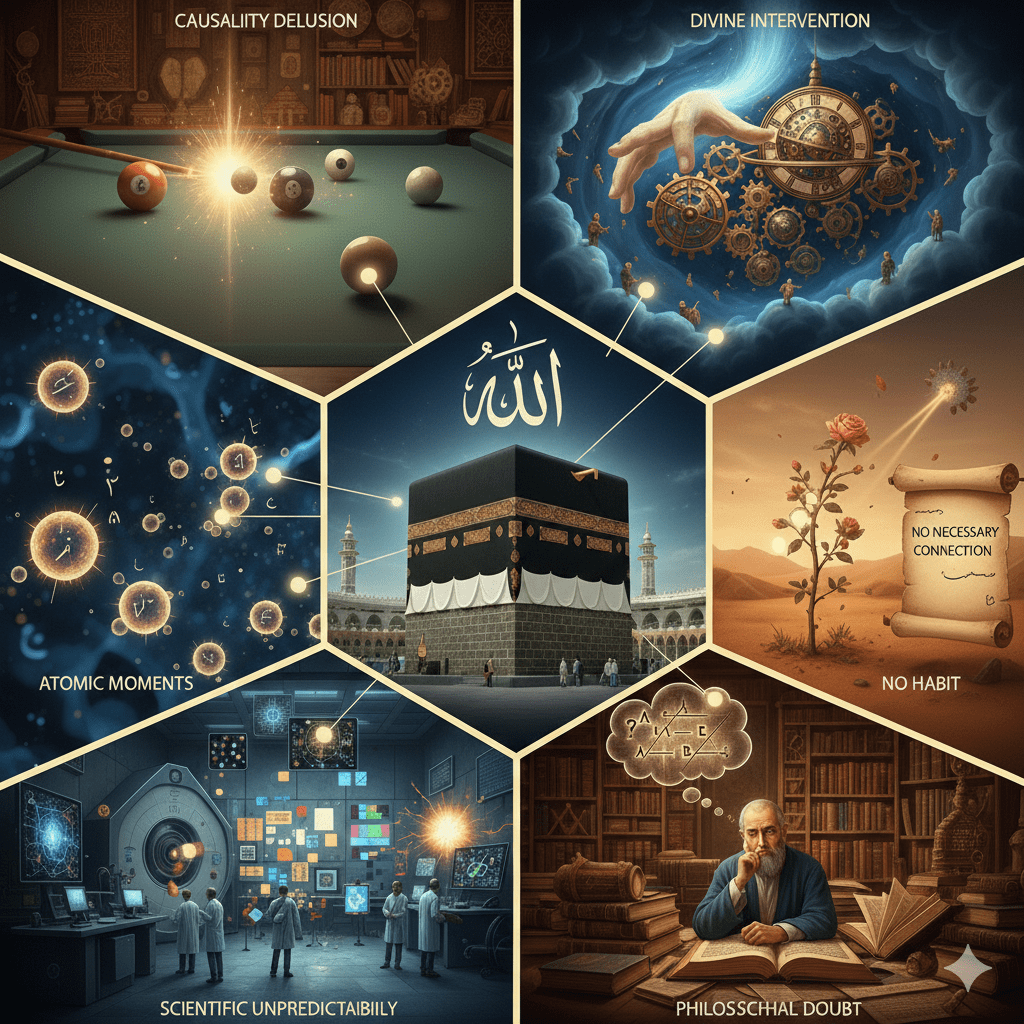

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism—understood as the claim that God alone is the true efficient cause, while “causes” in nature are regular sequences God freely maintains—is not a rejection of order, but a re-location of order: from intrinsic powers in created things to the immediate and continuous agency of God. This vision draws strength from the Quran’s repeated attribution of both outward events (rain, life and death, victory and defeat) and inward events (fear, resolve, intention) to divine action, while simultaneously affirming a reliable “way” (sunnah) by which God ordinarily governs the world.

Once read through this monotheistic lens, much of what modern agnostics and atheists present as evidence for determinism—lawlike regularity, the closure of physical description, the predictability (in principle) of events—can be reinterpreted as evidence of a single, comprehensive governance: an ordered cosmos whose regularities are best understood as divine constancy, not metaphysical necessity resident in matter. Even contemporary debates about consciousness and physicalism can be enlisted in this defense: where strict physicalism strains to explain subjectivity, occasionalism treats consciousness (and its linkage to bodily action) as squarely within God’s direct creative act.

Quranic foundations for denying creaturely causal power

Occasionalism does not begin as a technical metaphysics; it begins, in the Quran, as a theology of agency. The Quran repeatedly speaks in a way that pulls causal credit away from creatures—even when creatures are visibly involved—and assigns it to God as the decisive actor. The classic proof-text is 8:17, which explicitly negates independent creaturely efficacy in a context where human action is unmistakable: “It was not you… but it was Allah”—including the Prophet’s own act of throwing.

This verse is not merely devotional; it is metaphysical in implication. In the Ma‘arif al-Qur’an commentary preserved on Quran.com, the thrust is pedagogical but causally radical: believers are warned not to become intoxicated with “means,” because the outcome is not produced by human power alone but by divine enabling and determination—an instruction that “disengaged their minds from means and tied it up with the master-provider of all means.”

The same grammar of divine agency extends beyond human action to events commonly labeled “natural.” The Quran speaks of God sending rain and casting tranquility or drowsiness as reassurance (8:11), deliberately collapsing the modern distinction between “psychological state” and “meteorological process” into a single register of divine doing. It speaks of birds in flight and declares that “None holds them up except the Most Compassionate” (67:19), which—read occasionalistically—means that even what aerodynamics can describe remains, at the level of true agency, an act of moment-to-moment sustaining.

Likewise, the water we drink is framed not as an automatic product of impersonal cycles, but as a provision God can alter at will: humans do not “bring it down,” and God can make it undrinkably saline (56:69–70). The point is not to deny observable regularities (clouds precede rain; rivers follow storms), but to deny that such regularities are self-explanatory powers in the world.

The Quran also supplies occasionalism with a metaphysics of continuous governance. In 6:59, the Quran’s portrayal of divine knowledge is not distant but granular: a leaf does not fall without God’s knowing; nothing “moist or dry” escapes the encompassing record—language that naturalizes the idea of creation as continuously “kept in being,” not merely launched at the beginning of time. Complementing this is the famous “Be!” formula: when God wills a thing, “Be! And it is!” (36:82), which presents divine willing as sufficient without intermediary necessity. And 55:29 adds a rhythm of ceaseless divine activity: the world is not a wound-up clock but a reality in which “day in and day out” God is bringing about affairs.

Finally, occasionalism is strengthened by verses that locate divine agency inside the human subject. 8:24 declares that God “stands between” a person and their heart, a striking claim that intentions, resolutions, and inner turns are not sealed off from divine action but are themselves within God’s immediate governance. If inner life is included, occasionalism’s scope becomes total: not only fire and cotton, but also fear and courage, hesitation and resolve, are “occasions” for divine creative acts.

Al-Ghazali’s philosophical articulation and the logic of miracles

Al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is often associated with his critique of necessary causation in , where the paradigmatic example is fire and burning: we observe conjunction (fire-contact followed by burning) but do not grasp an intrinsic necessity that forces the effect to occur. In the framing offered by the , his central move is to deny that creaturely causes necessitate their effects in a way that would constrain divine omnipotence; any necessity robust enough to resist divine intervention is theologically unacceptable.

The deeper philosophical structure is twofold. First, the critique is modal: if two events are conceptually distinct, then (on al-Ghazali’s strategy) there is no logical contradiction in separating them; if there is no contradiction, then the alleged “necessity” of their connection is not demonstrable by reason alone. Second, the critique is epistemic: observation yields regularity, but observation alone does not identify who (or what) is the agent of the change. The account of Arabic-Islamic debates emphasizes this point: repeated observation shows that burning occurs at the juncture of contact, but does not establish that the fire is the true agent; that evidential situation is consistent with God being the active cause.

This is where occasionalism becomes a rational defense of miracles rather than a rejection of nature. If burning is not metaphysically locked to fire-contact, then miracles are not “logical violations,” but instances in which God produces a different sequence than the one humans habitually expect. The Quran itself gives a canonical exemplar: God commands the fire to be “cool and safe” for Abraham (21:69), making vivid the idea that fire’s burning is not an inviolable autonomous power. In other words, the miracle is not that God “breaks logic,” but that God is not bound by creaturely necessities that would make miracles impossible in principle.

A historically important nuance, however, is that modern scholarship disputes how “global” al-Ghazali’s occasionalism is—whether he is fully committed to denying all creaturely causation or leaves conceptual space for some secondary causality compatible with divine governance. The explicitly notes this interpretive divide, contrasting readings that treat him as a committed occasionalist with readings that see him as primarily defending the possibility of miracles while remaining open to some creaturely causation in a weaker sense. An overview likewise situates al-Ghazali’s “no necessary connection” move in the broader history of occasionalism, including later medieval and early modern developments.

Historically, this philosophical project is inseparable from al-Ghazali’s formation within Ash‘arite kalam and his encounter with philosophical necessitarianism associated with . The Ash‘arite concern is not to deny intelligibility but to protect a maximal doctrine of divine omnipotence and freedom against any metaphysical necessity in creatures. Even the biographical arc—his prominence as a teacher in at the and his later spiritual-intellectual crisis—highlights that al-Ghazali’s philosophical theology is never purely speculative but aimed at reorienting knowledge, agency, and certainty toward God.

God’s habit and why occasionalism can affirm scientific order

A frequent misunderstanding is that occasionalism implies chaos: if causes have no intrinsic power, why should the world be stable enough for science? The Quran itself supplies the answer by pairing divine omnipotence with a declared constancy in God’s “way” (sunnah): “you will find no change in Allah’s way” (33:62), and similarly, no diversion of it (35:43). The occasionalist interpretation is that the regularities we rely on are not metaphysical necessities of matter, but voluntary regularities of divine governance—stable because God is faithful, not because creation is self-sufficient.

This is where occasionalism can be presented as a metaphysics that underwrites scientific practice rather than negates it. In the philosophy of science, one influential way to regard “laws of nature” is as compact descriptions that systematize the patterns of the world, rather than as entities that themselves push events around. The best-known Humean strategy, associated with , treats laws as the axioms of the best balance of simplicity and strength among true descriptions. Occasionalism can gladly accept the descriptive success of laws—indeed, it expects such success if God acts with consistent wisdom—while denying that the “law” is an efficient cause.

The philosophical irony is that occasionalism converges in one respect with the empiricist critique of necessary connection strongly associated with : what we actually see are sequences and associations, not metaphysical glue. But occasionalism parts company with Hume at the decisive point: it does not stop at regularity; it identifies God as the true causal power behind the regularity. In this sense, occasionalism is neither a mere “regularity theory” nor a retreat into skepticism; it is a theological completion of an empiricist insight: observation alone reaches concomitance, while revelation and theology identify the ultimate agent.

This also clarifies why occasionalism can treat “natural causes” as real at the level of explanation without being real at the level of agency. Fire is a reliable sign; medicine is a reliable means; but neither is sovereign. The Quran.com tafsir on 8:17 captures the spiritual-epistemic payoff: it “ties” the mind to the giver of means, resisting the human tendency to absolutize instruments into ultimate causes.

Determinism becomes evidence for occasionalism under monotheism

The most provocative apologetic claim in your prompt can be made precise: the same empirical data that motivates causal determinism can be reinterpreted as support for occasionalism once monotheism is admitted as a live explanatory hypothesis.

“Causal determinism,” as defined in analytic philosophy, is roughly the thesis that every event is necessitated by antecedent conditions together with the laws of nature. When agnostics or atheists argue for determinism, they often appeal to the success of physics, the apparent closure of explanation under laws, and the ubiquity of regularity. But occasionalism replies: those phenomena—regularity, comprehensiveness, systematic order—are exactly what a world governed by one sovereign will should look like, especially if God’s “way” does not change.

On this view, determinism’s rhetoric of all-encompassing governance becomes almost Quranic in tone—except that it replaces “God conducts every affair” (10:31) with “laws conduct every affair.” The Quran challenges that substitution directly by insisting that governance (tadbīr) belongs to God and that humans, when honestly pressed, implicitly recognize this. Occasionalism thus proposes a reinterpretation: what the determinist calls lawlike necessity is, ontologically, divine decree habitually executed.

This interpretive shift also reframes a deep philosophical puzzle in determinism: what makes laws lawlike? Contemporary metaphysics of laws is divided between views that treat laws as descriptive regularities and views that treat laws as relations with some sort of necessity or governing force. Occasionalism offers a theistic answer: lawlikeness is grounded in the reliability of divine willing—God’s constancy, not matter’s metaphysical governance. The “necessity” involved is not a brute metaphysical feature of the universe; it is a stability of divine action (sunnah).

Modern physics adds an important further point: even if determinism is attractive in some frameworks, physics does not deliver a single settled metaphysical conclusion. Quantum theory has mainstream interpretations commonly associated with indeterminism (often grouped under “Copenhagen”), while also allowing deterministic reconstructions such as Bohmian mechanics. Chaos theory adds another nuance: systems can be deterministic and yet practically unpredictable due to sensitive dependence on initial conditions. Occasionalism is not threatened by these options, because it does not hinge on whether nature is deterministic or probabilistic; it hinges on the thesis that whatever occurs—deterministically or probabilistically—occurs by God’s direct enactment and sustaining.

In this light, the determinist’s insistence that events do not “pop into being uncaused” becomes, under monotheism, an argument against creaturely self-sufficiency rather than against divine agency: nothing in creation is self-originating; everything is contingent; God alone is the sufficient ground of the sequence. This is precisely the intuition al-Ghazali presses when he denies that observation establishes the inanimate as an “agent” and insists that God enacts the change.

Consciousness, physicalism, and the appeal of divine agency

A second axis of “evidence” often deployed by atheistic determinists is the philosophy of mind: if mental life is wholly physical, and the physical is law-governed, then free agency is illusion and God is explanatorily unnecessary. Yet much contemporary philosophy of mind argues that consciousness is precisely where strict physicalism faces its most severe explanatory strain. The describes consciousness as central and deeply puzzling, with no agreed-upon theory that cleanly places it within nature. The “hard problem” tradition highlights the gap between functional/structural explanation and subjective experience—why there is “something it is like” to be a subject.

It is in this register that Zia H Shah’s 2025 essay is intended to destabilize metaphysical naturalism: he argues that physicalism is not merely contested but incomplete in the face of consciousness. In his own words, he claims that the physicalist paradigm “is incomplete as an account of reality,” especially because it struggles to accommodate the richness of conscious life. Whatever one finally concludes about that debate, the strategic upshot for occasionalism is clear: if physicalism is not forced upon us, then the atheistic determinist inference (“determinism ⇒ no God”) is weakened at its root.

Occasionalism then offers a distinctive advantage: it supplies a unified account of both physical regularities and mental life without requiring that mind be reduced to matter or that matter possess intrinsic necessitating powers. In classical Ash‘arite framing, God creates acts while humans “acquire” them (kasb), preserving moral responsibility without making the creature an independent creator. A concise statement of this doctrine is captured in ’s definition: actions are originated by God and “acquired” by humans. The Arabic-Islamic causation entry in the similarly notes kasb as an Ash‘arite tool for affirming a created power that is real in the subject yet remains under divine control.

Notably, this doctrine aligns naturally with the Quranic interiorization of divine agency: God stands “between a person and their heart” (8:24), meaning that the very space in which intentions arise is not metaphysically sealed off from God. Under occasionalism, the bridge between intention and bodily motion is not an inexplicable “mental causation” puzzle inside a closed physical system; it is a locus of divine enactment in which the human will is morally relevant but not metaphysically sovereign.

Epilogue: the Quranic call from causality to worship

The thematic culmination of this defense is not an abstract metaphysics but a Quranic reorientation of the mind. The Quran’s argument in 10:31–36 is almost a liturgy of occasionalism: it presses the listener to admit that provision, perception, life and death, and the governance of “every affair” belong to God. Once that admission is made, the Quran draws the existential consequence: if God is the True Lord, “what is beyond the truth except falsehood?” (10:32). And it criticizes the epistemic posture of those who cling to inherited assumptions and conjecture: “assumptions can in no way replace the truth” (10:36).

Zia H Shah’s commentary published on February 7, 2026 frames these verses as a discourse that “intertwines theology, philosophy, and even insights that resonate with science,” and he explicitly presents a multi-lens reading (theological, scientific, philosophical) meant to show how Quranic reasoning dismantles idolatry by leading opponents to answer their own questions. Read occasionalistically, this is not merely an anti-idol polemic against ancient statues; it is also a polemic against the modern idol of self-subsisting causality—against treating “nature” as an autonomous rival to the divine.

The ethical payoff is not passivity. The Quranic logic of 8:17 does not deny that humans act; it denies that humans are ultimate agents. The Ma‘arif al-Qur’an tafsir makes this explicit by describing how the verse frees believers from pride and reattaches their sense of efficacy to God without negating struggle or responsibility. In the same spirit, occasionalism invites a disciplined causal humility: study the patterns of the world as God’s stable “way” (33:62; 35:43), use means as God’s ordinary instruments, but never absolutize the instruments into rivals of the One who, at every instant, says “Be!” and it is.

For references go to Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment