Epigraph

If two groups of the believers fight, you [believers] should try to reconcile them; if one of them is [clearly] oppressing the other, fight the oppressors until they submit to God’s command, then make a just and even-handed reconciliation between the two of them: God loves those who are even-handed. The believers are brothers, so make peace between your two brothers and be mindful of God, so that you may be given mercy. (Al Quran 49:9-10)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio teaser:

Abstract

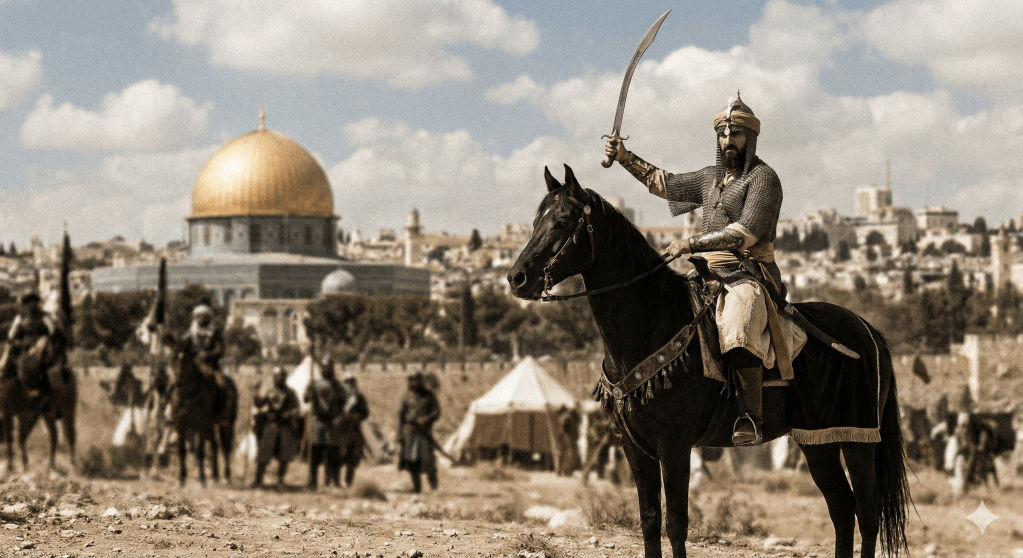

This comprehensive research report investigates the cyclical phenomenon of political fragmentation and theological paralysis within the Islamic world, utilizing the catastrophic failure to repel the First Crusade (1096–1099) as a primary historical case study. The analysis posits that the 11th-century geopolitical inertia was not merely a military failing but a structural defect caused by the deep sectarian schism between the Sunni Seljuk Empire and the Shia Fatimid Caliphate. This division, which rendered the Dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) incapable of a coordinated defense, was only rectified through the grand strategy of Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (Saladin), who operationalized the Quranic injunctions of Surah Al-Hujurat (49:9–10) to dismantle the Fatimid state and forcibly unify the Levant.

The report subsequently bridges this medieval history with the contemporary crisis facing the Muslim Ummah: the resurgence of violent sectarianism and the consequent rise of atheism and metaphysical naturalism among Muslim youth. Drawing on sociological data from the Arab Barometer and the theological corpus of Dr. Zia H. Shah, we argue that modern sectarian dogmatism acts as a repulsive force, driving the younger generation toward secular humanism. The report concludes that a scientific and philosophical presentation of Quranic Monotheism (Tawhid)—one that harmonizes revelation with modern cosmology, biology, and consciousness studies—offers the only viable “intellectual Saladin” for the 21st century. This approach transcends sectarian bickering by anchoring the faith in the universal, observable truths of the natural world, thereby neutralizing the existential doubts of the modern age.

Part I: The Anatomy of Paralysis — The First Crusade (1096–1099)

1.1 The Geopolitical Mosaic of the 11th Century

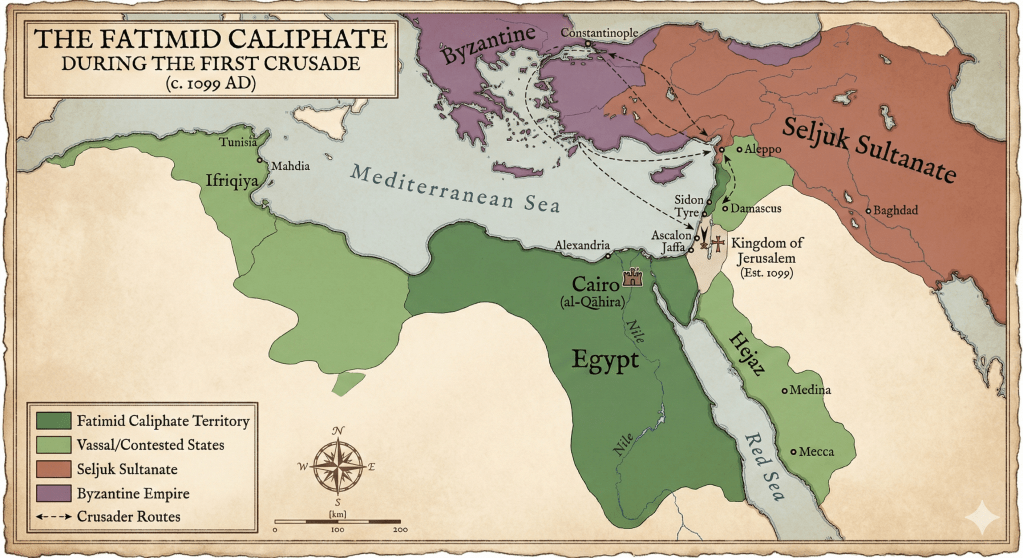

On the eve of the First Crusade, the Near East was a region characterized by profound political entropy. The monolithic power of the early Abbasid Caliphate had long since evaporated, leaving behind a fragmented landscape of warring principalities, each prioritizing local hegemony over collective security.1 While the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad retained symbolic spiritual authority as the Commander of the Faithful (Amir al-Mu’minin), executive power had been usurped by the Seljuk Turks, a martial dynasty from the steppes that had revitalized Sunni Islam in the 11th century but had subsequently fallen victim to its own dynastic infighting.2

The death of the powerful Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I in 1092, followed shortly by his formidable vizier Nizam al-Mulk, triggered a vacuum of authority that plunged the Sunni world into a chaotic succession crisis. By 1096, the Great Seljuk Empire had fractured into rival sultanates in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia (the Sultanate of Rum), ruled by brothers and nephews who viewed one another with greater suspicion than they did any external threat.2 This internal Sunni fragmentation, however, was merely one dimension of the catastrophe.

1.1.1 The Sunni-Shia Fault Line: The Cold War of the Middle Ages

The most significant debilitation of the Muslim world was the ideological and geopolitical chasm separating the Sunni Seljuks from the Ismaili Shia Fatimid Caliphate based in Cairo. This was not a mere political rivalry; it was a theological “Cold War” where each side regarded the other as an existential heresy.3 The Fatimids, claiming descent from the Prophet’s daughter Fatima, rejected the legitimacy of the Abbasid Caliphs and the Seljuk Sultans, actively sponsoring missionary (da’wa) activities to undermine Sunni rule in Syria and Iraq.

This schism created a bipolar world where the concept of a unified “Muslim response” was structurally impossible. When reports reached the Levant of armed Frankish hosts moving through Byzantium, the initial reaction among Muslim rulers was not one of pan-Islamic solidarity, but of calculated indifference or opportunistic maneuvering.3

1.2 The Failure of Response: A Tragedy of Strategic Myopia

The success of the First Crusade was a function of Muslim disunity rather than Frankish military superiority. The Crusader march through Anatolia and into the Levant exploited the fractures of the Islamic polity with surgical precision.

1.2.1 The Miscalculation at Antioch and the Fatimid Betrayal

The depth of the Muslim paralysis is best illustrated by the events surrounding the Siege of Antioch (1097–1098). As the Crusaders laid siege to this critical Seljuk stronghold, the Fatimid Vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah in Cairo saw an opportunity not to defend Islam, but to cripple his Sunni rivals. Mistaking the Crusaders for Byzantine mercenaries whose ambitions were limited to Northern Syria (territory held by the Seljuks), the Fatimids engaged in diplomatic overtures with the Franks.1

Historical chronicles record that Fatimid envoys met with the Crusaders to propose a partition of the region: the Franks could take Syria (thereby weakening the Seljuks) if they left Palestine and Jerusalem to Fatimid control. This strategic myopia was so profound that Egyptian envoys reportedly participated in a joint celebration with the Crusaders after a battle against a Turkish relief force, oblivious to the fact that the Franks intended to conquer Jerusalem itself.3 This betrayal allowed the Crusaders to grind down the isolated Seljuk garrisons in Antioch while the Fatimids seized Jerusalem from the Turks in 1098, only to face the Crusader onslaught alone a year later.4

1.2.2 The Fall of Jerusalem (1099) and the Silence of Baghdad

When the Crusader army finally marched on Jerusalem in 1099, the city was defended by a Fatimid garrison that had only recently wrestled control from the Seljuks. There was no coordinated relief force. The Sunni princes of Damascus and Aleppo, paralyzed by their own rivalries and fear of Fatimid expansion, remained in their citadels. The Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Al-Mustazhir, though petitioned by refugees carrying the hair of women shorn in grief, was powerless to mobilize the feuding Seljuk princes.5

The result was the massacre of Jerusalem’s population—Muslims and Jews alike—and the establishment of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The city’s fall was a direct consequence of the violation of the Quranic imperative of brotherhood. The Muslims of the Levant had prioritized sectarian Realpolitik over the “Command of Allah,” resulting in the loss of their third holiest site.4

1.3 The Theological Void: A Crisis of Priorities

The political fragmentation was mirrored by an intellectual stagnation. While the 11th century was a period of rich intellectual output—this was the era of Al-Ghazali—the political theology of the time had not yet formulated a coherent response to the Crusader threat. The concept of Jihad had largely fallen into abeyance as a state obligation, often relegated to the frontiers or interpreted solely as a spiritual struggle by Sufi orders withdrawing from the corruption of public life.7

The Ulama (scholars) were deeply entrenched in sectarian polemics, debating the nuances of jurisprudence (Fiqh) or refuting the esoteric claims of the Batiniyya (Ismailis), rather than addressing the existential threat from the West. It would take nearly a century for the Muslim world to reconstruct the intellectual and political infrastructure necessary to reverse the losses of 1099. This reconstruction required a leader who understood that military victory against the Franks was impossible without first curing the “Fitna” (civil strife) of the Muslim body politic.

Part II: The Quranic Imperative — Analysis of Surah Al-Hujurat 49:9-10

To understand the legal and theological basis for the subsequent unification under Saladin, one must examine the Quranic verses that govern internal conflict. Surah Al-Hujurat (49:9–10) provides the constitutional framework for conflict resolution and the use of force within the community of believers.

2.1 The Verse of Reconciliation and Rebellion

“And if two factions among the believers should fight, then make settlement between the two. But if one of them oppresses the other, then fight against the one that oppresses until it returns to the command of Allah. And if it returns, then make settlement between them in justice and act justly. Indeed, Allah loves those who act justly. The believers are but one brotherhood, so make peace between your brothers and fear Allah that you may receive mercy.” (Quran 49:9–10) 8

This verse establishes a three-stage protocol for handling internal dissent:

- Mediation (Islah): The primary obligation is to broker peace between warring factions.

- Combating Transgression (Baghi): If one party rejects mediation or aggresses against the other, they are designated as the “transgressing party” (Fi’ah al-Baghiya). The community is then commanded to fight this group—not to destroy them, but to compel their return to the “Command of Allah” (Amr Allah).

- Restoration of Justice (Adl): Once the rebellious group submits, they are to be reintegrated into the community with justice, ensuring no lingering grievances fuel future conflict.10

2.2 Classical Exegesis and Political Application

Classical commentators provided the jurisprudential nuance that allowed leaders like Saladin to apply this verse to political rivals.

- The Definition of “Command of Allah”: Exegetes like Al-Tabari and later Ibn Kathir explained that the “Command of Allah” refers to the Sharia and the consensus of the community. A group that breaks the unity of the Muslims during a time of existential threat is viewed as having abandoned the “Command,” thereby justifying the use of force against them until order is restored.10

- The Legitimacy of War Against Muslims: This verse was critical in distinguishing between legitimate Jihad (against external aggressors) and the necessary police action against internal rebels (Bughat). It provided the theological cover for a Sunni Sultan to wage war against other Muslim princes—Sunni or Shia—who refused to join the collective defense. The goal of such a war was not conquest but Ta’lif (harmonization) and Tawhid (unification).13

2.3 The Brotherhood Clause

Verse 49:10 reinforces the metaphysical reality of the Ummah: “The believers are but one brotherhood.” This ontological status supersedes tribal, ethnic, or political affiliations. The failure of the Muslims in 1099 was fundamentally a failure to uphold this ontological truth. By allowing the Franks to slaughter the inhabitants of Jerusalem while they bickered over territory, the Muslim princes had severed the bonds of brotherhood, incurring the divine disfavor implied in the verse.15

Part III: Saladin’s Grand Strategy — Unification as a Prerequisite for Liberation

3.1 The Rise of Saladin and the End of the Fatimids

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (Saladin) emerged from the retinue of Nur ad-Din Zengi, a ruler who had begun the process of Sunni revivalism in Syria. However, Saladin’s strategic vision transcended that of his master. He recognized that the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem was sustained by the division between the rich Nile Valley (Egypt) and the manpower of Syria. As long as Egypt was ruled by the Fatimids, who were hostile to the Sunni Zengids, the Crusaders could play one side against the other.17

3.1.1 The Abolition of the Caliphate (1171)

In a move of profound historical consequence, Saladin, acting as Vizier in Egypt, abolished the Fatimid Caliphate in 1171. He ordered the Friday sermon (Khutbah) to be read in the name of the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, thereby ending two centuries of Ismaili rule in Egypt.17 This was not merely a change of government; it was the healing of the great schism. By bringing Egypt back into the Sunni fold, Saladin united the economic resources of the Nile with the military traditions of the Turks and Kurds.

3.2 Operationalizing Quran 49:9: The War of Unification

Following the death of Nur ad-Din in 1174, Saladin spent the next decade fighting not the Crusaders, but other Muslims. The Zengid princes of Aleppo and Mosul, jealous of his power and fearful of his ambition, refused to recognize his leadership. They even sought alliances with the Crusaders to check Saladin’s expansion—a repetition of the errors of 1099.4

Saladin and his scholarly advisors, including the chronicler Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani and the jurist Ibn Qudama, framed these campaigns through the lens of Quran 49:9. The Zengid princes were cast as the Fi’ah al-Baghiya—the transgressing faction that prioritized dynastic ego over the defense of Islam. Saladin argued in his letters to the Caliph in Baghdad that he was fighting these princes only to bring them back to the “Command of Allah,” which in this context meant a unified front against the infidel invader.19

This justification was crucial. It allowed Saladin to maintain the moral high ground. He did not sack the Muslim cities he conquered; he integrated their garrisons into his army and often reappointed the defeated princes as his vassals, fulfilling the Quranic command to “make settlement between them in justice” once they submitted.22

3.3 The Propaganda of Jihad and the “Merits of Jerusalem”

To cement this unity, Saladin waged a war of ideas. He revitalized the genre of Fada’il Bayt al-Maqdis (The Merits of Jerusalem), commissioning books and sermons that extolled the sanctity of Jerusalem. These works were read in the marketplaces and mosques of Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo, creating a shared spiritual longing that transcended regional loyalties.20

Scholars like Al-Ghazali (in his political theory regarding the necessity of a strong Sultanate) and later Ibn Taymiyyah (reflecting on this era) supported the idea that the unity of the community was a supreme religious value. The Sultan, acting as the sword of the Caliph, was authorized to suppress dissent to protect the Dar al-Islam.7

3.4 The Fruit of Unity: The Battle of Hattin (1187)

The culmination of this strategic unification was the Battle of Hattin in July 1187. For the first time in nearly a century, the armies of Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia marched under a single command. The unity of command allowed Saladin to execute a complex tactical encirclement, trapping the Crusader army in a waterless plain and decimating them.23

Following the victory at Hattin, Jerusalem surrendered to Saladin in October 1187. The liberation of the city was not a miracle; it was the logical result of the political and theological unification of the Muslim world. Saladin had proven that the “Command of Allah” (unity) was the prerequisite for victory.4

Part IV: The Modern Recurrence — Sectarianism in the 21st Century

4.1 The Return of the 11th Century

In the 21st century, the Muslim world bears a haunting resemblance to the fractured landscape of the pre-Saladin era. The geopolitical rivalry between major regional powers—often framed as a binary conflict between a Sunni bloc and a Shia bloc—mirrors the Seljuk-Fatimid divide of the 1090s. Proxy wars in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq have devastated the region, turning the heartlands of Islamic civilization into battlegrounds where Muslim factions slaughter one another with weapons supplied by external powers.25

4.1.1 The Sectarian Virus and the “Baghi” of Today

The violence witnessed in recent decades—mosque bombings, ethnic cleansing, and the institutionalized Takfir (excommunication) of rival sects—has created a profound crisis of legitimacy. In the medieval context, the Baghi (transgressor) was a rebel prince; today, the transgressor is often the sectarian militia or the state actor that weaponizes religious identity for political survival. The “Command of Allah” to make peace (49:9) is routinely ignored in favor of zero-sum conflicts that weaken the entire Ummah and invite foreign intervention, much as the Fatimids invited the Crusaders.27

4.2 The Sociological Cost: Alienation of the Masses

Just as the 11th-century chaos alienated the masses from their rulers, modern sectarian violence has alienated the youth from the faith itself. When “Islam” is presented primarily as a banner for militia violence, corrupt governance, or intolerant dogmatism, the religion ceases to be a source of spiritual solace and becomes a source of cognitive dissonance. The sight of Muslims killing Muslims while shouting “Allahu Akbar” creates a theological crisis that traditional clerics—often viewed as complicit in the sectarian narrative—are unable to resolve.29

The following table illustrates the parallel dynamics between the 11th and 21st centuries:

| Historical Dynamic (11th Century) | Modern Parallel (21st Century) | Consequence |

| Seljuk-Fatimid Rivalry | Saudi-Iran / Sunni-Shia Geopolitics | Paralysis of collective action; reliance on external powers. |

| Fatimid-Crusader “Alliance” | Proxy Alliances with Global Powers | Loss of sovereignty; destruction of local infrastructure. |

| Sectarian Takfir | ISIS / Militia Sectarianism | Delegitimization of moral authority; internal bloodshed. |

| Retreat to Sufism/Apathy | Rise of Atheism / “Ex-Muslims” | The youth abandon the public square or the faith entirely. |

Part V: The Crisis of Faith — The Rise of Atheism Among Muslim Youth

5.1 Quantifying the Shift: The Arab Barometer Data

Unlike the medieval period, where disillusionment might lead to heterodoxy or withdrawal, the modern reaction to religious chaos is increasingly a rejection of the metaphysical itself. Data from the Arab Barometer, a rigorous quantitative research network, indicates a significant and unprecedented shift in religious identification among Arab youth.

- The Rise of the “Nones”: The 2019 survey wave found that the percentage of Arabs identifying as “not religious” rose from 8% in 2013 to 13% in 2019. This trend is most pronounced among the youth (under 30), where the figure reached 18% across the region.31

- The Tunisian Anomaly: In Tunisia, a country with a strong secular heritage but also a history of Islamist political activism, nearly half of the youth (46%) described themselves as “not religious” in 2019. This statistic rivals the rates of secularization seen in the United States and Western Europe.32

- Trust in Religious Leaders: The credibility of the religious establishment has collapsed. In 2013, approximately 51% of respondents in the region expressed “great” or “medium” trust in religious leaders. By 2018, this number had fallen to 40%. Trust in Islamist political parties dropped even more precipitously, falling by over a third.32

5.2 The Mechanisms of Disbelief

The rise of the “Ex-Muslim” identity is not merely a result of Western cultural influence; it is a direct byproduct of the internal dysfunction of the Muslim world.

5.2.1 The Moral Argument Against Religion

Young Muslims, exposed to the brutal realities of sectarian conflict (e.g., the atrocities of ISIS, the starvation in Yemen), are asking a fundamental moral question: If this violence is the result of religion, is religion inherently evil? The inability of traditional theology to convincingly disown sectarian violence leads many to conclude that the problem lies in the text itself, rather than its interpretation.26

5.2.2 The Intellectual Deficit

Furthermore, the traditional curriculum of the Madrasa, focused on medieval jurisprudence and polemics, often fails to address the existential questions posed by modern science. When a young student asks about evolution, the Big Bang, or the nature of consciousness, they are often met with dogmatic rejection or silence. This intellectual gap drives them toward the coherent, albeit materialist, narratives offered by secular science and “New Atheism”.30

The crisis, therefore, is twofold: a moral rejection of sectarianism and an intellectual rejection of perceived anti-scientific dogma. To reverse this, a new “Saladin” is needed—not a military general, but an intellectual paradigm shift that reunifies the Muslim mind by reconciling the moral and the scientific.

Part VI: The Scientific and Philosophical Remedy — The Work of Dr. Zia H. Shah

The solution to the twin crises of sectarian fragmentation and rising atheism lies in a return to the core of the Quran: strict Monotheism (Tawhid), articulated through the universal language of science. This approach, championed by Dr. Zia H. Shah and the The Quran and Science project, posits that scientific inquiry is the most potent form of Tafsir (commentary) for the modern age.

Just as Saladin united the Muslims under the banner of the Abbasid Caliphate (a symbol of orthodox unity), the modern Ummah must be united under the banner of Scientific Monotheism. Gravity, genetics, and cosmology do not have sects. A Sunni and a Shia are equally subject to the laws of physics. By shifting the focus from divisive jurisprudential history to the undeniable truths of God’s Creation, we can forge a new common ground that is empirically robust and spiritually satisfying.30

6.1 The Philosophical Incoherence of Atheism

To reclaim the youth, Islamic theology must go on the offensive, utilizing superior philosophical arguments to dismantle the certainty of materialist atheism. Dr. Zia H. Shah’s work highlights the “Philosophical and Scientific Incoherence of Atheism,” arguing that naturalism fails to explain the most fundamental aspects of reality.34

6.1.1 The Hard Problem of Consciousness: The “Prior Mind”

The most significant Achilles’ heel of the atheistic worldview is the “Hard Problem of Consciousness.” Materialism asserts that matter, time, and physical laws are sufficient to explain the universe. However, there is no mechanism in physics by which inert atoms (carbon, hydrogen) can give rise to the subjective experience (Qualia) of love, pain, or the color red.

- The Failure of Materialism: Dr. Shah argues that describing the brain’s electrochemical activity does not explain why that activity feels like something. The “Explanatory Gap” remains unbridged by neuroscience.37

- The Critique of Panpsychism: Some atheists, realizing this gap, turn to panpsychism (the idea that all matter has proto-consciousness). Dr. Shah dismisses this as a “metaphysical Hail Mary” that suffers from the “Combination Problem” (how do a billion micro-conscious atoms combine to form one unified “I”?).37

- The Theistic Solution: The only coherent explanation is that consciousness is fundamental, not emergent. It is a reflection of a “Prior Mind”—the Divine Consciousness. This aligns with Quran 17:85: “They ask you concerning the soul (Run). Say: The soul is of the command of my Lord…”.38

By centering the debate on consciousness, Muslims can argue that God is not a “Sky Fairy” but the Necessary Reality that grounds our own existence.

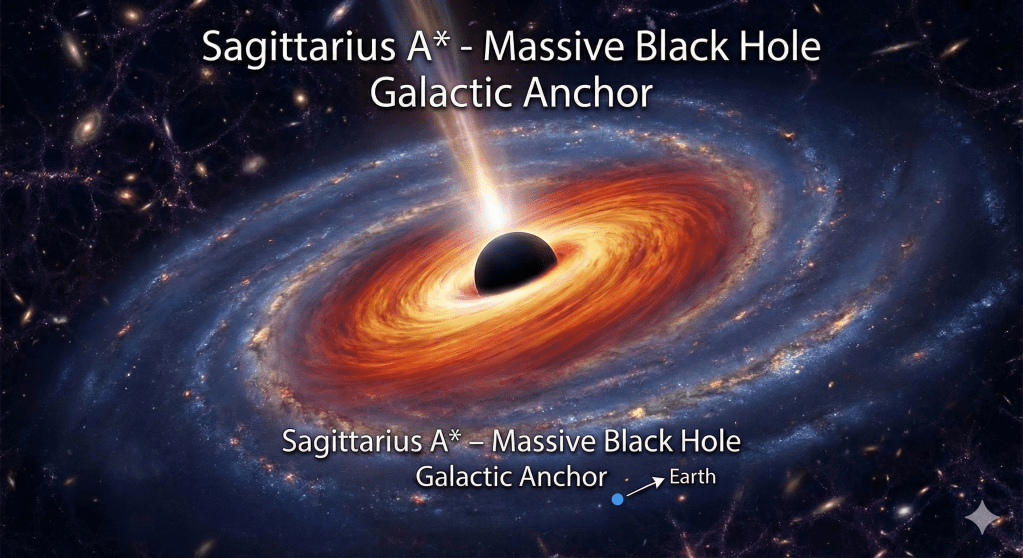

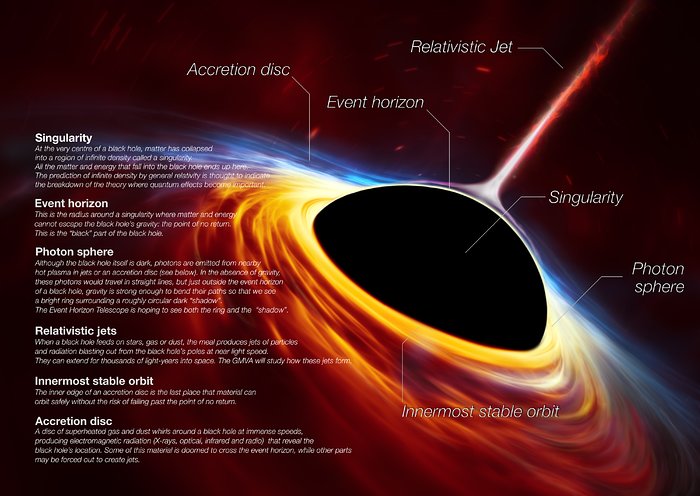

6.2 The Cosmological Argument: One God, One Universe

The “One God, One Universe” argument posits that the exquisite order and “Fine-Tuning” of the cosmos point to a single, unified Creator. This is the scientific application of Tawhid.

- Unity of Law: The universe operates under the same physical laws from the atom to the galaxy. The electromagnetic force constant (approx. 1/137) is fine-tuned to a degree where even a microscopic deviation would render stars, chemistry, and life impossible. This “Unity of Law” reflects the “Unity of the Lawgiver”.40

- Quran 21:22: “If there had been in the heavens or earth any gods but Him, both heavens and earth would be in ruins.” This verse is validated by modern physics; a universe governed by competing physical laws (polytheism) would be chaotic and uninhabitable.

- Refuting the Multiverse: Dr. Shah critiques the atheistic appeal to a “Multiverse” as a desperate attempt to explain fine-tuning without God. Since other universes are unobservable, the Multiverse is a “God of the Gaps” for atheists—a belief based on faith, not evidence.40

6.3 Scientific Exegesis: Validating the Quran for the Modern Mind

A key component of this remedy is Scientific Tafsir: interpreting Quranic verses through the lens of established science to demonstrate their divine origin. This bypasses sectarian disputes, as the scientific facts are neutral and universal.

6.3.1 The Big Bang and Quran 21:30

“Do not the disbelievers see that the heavens and the earth were a closed-up mass (Ratqan), then We opened them out (Fataqnahuma)? And We made from water every living thing…” (Quran 21:30)

- Traditional View: Early commentators interpreted “Ratqan” as the sky holding back rain.

- Modern Scientific View: Dr. Shah and other modern scholars identify “Ratqan” (a fused mass) with the Cosmological Singularity and “Fataqnahuma” (splitting/opening) with the Big Bang/Inflation. This interpretation aligns the Quranic narrative with the standard model of cosmology, offering a powerful intellectual validation for the modern believer.41

6.3.2 Guided Evolution

To address the conflict between biology and faith, Dr. Shah advocates for a “Theistic Evolutionary” model.

- Quran 71:14: “While He has created you in stages?”

- Quran 29:20: “Travel through the earth and observe how He began creation.”

- Synthesis: Evolution is the mechanism of creation; God is the Agent. By accepting evolution as “Guided,” Muslims can reconcile their faith with modern biology, removing a major stumbling block for the youth. This position moves the debate from “Creation vs. Evolution” to “Blind Evolution vs. Guided Evolution”.44

6.4 The “Unity of Truth” as the Antidote to Sectarianism

The ultimate strength of this approach is its potential to unify. The sectarian debates that fueled the disaster of 1099 and the proxy wars of today are based on historical grievances and jurisprudential minutiae. In contrast, the “Book of Nature” is shared by all.

- Neutral Ground: When a Sunni and a Shia study the fine-tuning of the universe or the complexity of DNA, they stand on common ground. The awe inspired by the scientific study of creation fosters a “Cosmic Spirituality” that transcends sectarian labels.30

- Democratizing Authority: This approach empowers the Ulul Albab (People of Understanding)—scientists, doctors, and educated laypeople—to engage with the Quran. It breaks the monopoly of the traditional clergy who have often been the custodians of sectarianism.46

Epilogue: The Eternal Mandate

The history of the First Crusade stands as a stark warning across the centuries: division is the precursor to destruction. The Muslims of the 11th century paid for their disunity with the blood of Jerusalem. It was only when Saladin wove the disparate threads of the Ummah back into a single tapestry—using the legal and spiritual imperative of Quran 49:9–10—that victory became possible.

Today, the “Crusade” facing the Muslim world is not a military invasion, but an ideological crisis. The “Frankish knights” are the arguments of aggressive atheism and the nihilism of secular materialism. The “Fatimid betrayal” is the internal rot of sectarian violence that delegitimizes the faith in the eyes of its own children.

The solution remains the same: Unity. However, the mechanism of unity has evolved. We cannot unify solely behind a Sultan with a sword; the age of empires is over. We must unify behind an Idea—the undeniable, scientifically validated Truth of Quranic Monotheism.

By presenting Islam not as a sect of history but as the rational soul of the universe—supported by the testimony of the stars, the cell, and the human consciousness—we can bring the youth “back to the command of Allah.” This “Intellectual Saladin” will not conquer territory, but it will conquer hearts and minds, defeating the specter of atheism and reclaiming the intellectual Jerusalem of our age.

“Indeed, this Ummah of yours is one Ummah, and I am your Lord, so worship Me.” (Quran 21:92)

Analysis of Key Historical Dynamics

To fully grasp the depth of the 11th-century betrayal and the subsequent recovery, it is necessary to scrutinize the specific mechanisms of the Fatimid-Crusader interaction and Saladin’s counter-strategy.

The Mechanism of Fatimid-Crusader Collaboration

The diplomatic exchanges between the Fatimids and the Crusaders reveal the extent to which sectarianism blinded Muslim leadership to reality. The Fatimids, Ismaili Shias, viewed the Sunni Seljuks as usurpers of the Caliphate and the primary threat to their existence. This theological delegitimization allowed the Fatimid Vizier, Al-Afdal Shahanshah, to view the Crusaders (Franks) as merely another mercenary force—a tool to be used against the Turks, much like the Byzantines had been used in the past.3

Table 1: Strategic Divergence in 1098

| Faction | Capital | Sect | Strategic Goal (1096-1099) | Relationship to Crusade |

| Seljuks | Isfahan/Baghdad | Sunni | Maintain fragmentation; local survival; defeat Fatimids. | Victims (Defeated at Nicaea, Dorylaeum, Antioch). |

| Fatimids | Cairo | Ismaili Shia | Retake Jerusalem from Seljuks; secure Egypt from Turkish invasion. | Tacit Allies (Initially viewed Franks as anti-Seljuk partners; proposed partition of Levant). |

| Abbasids | Baghdad | Sunni | Survival of the Caliphal institution; managing Seljuk princes. | Impotent Observers (Unable to project military force). |

Insight: The Fatimids re-conquered Jerusalem from the Seljuk Turks in August 1098 while the Crusaders were besieging the Seljuks in Antioch. They exploited the Crusader pressure on the Turks to seize Palestine. When the Crusaders turned south in 1099, the Fatimids were shocked—they had assumed the Franks would be satisfied with Northern Syria. This miscalculation—thinking religious enemies were preferable to sectarian rivals—is the classic error of disunity that Saladin later sought to correct.

Saladin’s Application of Quran 49:9

Saladin’s genius lay in his ability to frame his war against other Muslims as a “War for Peace” (pacification). Using the Baghi (rebellion) clause of 49:9, he created a legal framework for unification:

- Mediation (Islah): Saladin initially sought alliances with the Zengids of Aleppo and Mosul after Nur ad-Din’s death, proposing a confederation against the Franks.

- Transgression (Baghi): When the Zengid princes refused and allied with the Franks to check Saladin’s power (e.g., Aleppo calling on Crusaders for help in 1175), they became “Transgressors” in the eyes of the law.

- Correction (Qital): Saladin fought them not to destroy them, but to force them into the unified front. Once they submitted (“returned to the command”), he often restored them to their governorships as vassals, rather than executing them. This ensured their resources remained available for the Jihad.17

- Justice (Adl): He cemented these alliances through marriage (e.g., marrying Nur ad-Din’s widow) and by respecting the local autonomy of the submitted princes, provided they supplied troops for the war against Jerusalem.

Sociological Data: The Modern “Fitna”

The following table synthesizes data regarding the correlation between sectarian violence and the rise of non-religiosity, drawing from the Arab Barometer and qualitative studies on the “Ex-Muslim” phenomenon.

Table 2: The Sectarian Driver of Atheism

| Factor | Mechanism of Disillusionment | Statistical Trend (Arab Barometer 2013-2019) |

| Sectarian Violence | Witnessing atrocities committed in the name of God (ISIS, militias) creates cognitive dissonance. | Trust in Islamist parties dropped by ~33% region-wide.32 |

| Clerical Hypocrisy | Perception of religious leaders as political pawns fueling division rather than spirituality. | Trust in religious leaders fell from 51% to 40%.32 |

| Youth Bulge | Young people (under 30) feel disconnected from archaic sectarian grievances. | % of “Not Religious” youth (under 30) rose to 18% region-wide.31 |

| Digital Access | Exposure to “New Atheist” arguments and scientific critiques of religion online. | High correlation with internet penetration in Tunisia/Egypt (46% non-religious youth in Tunisia).32 |

Insight: The rise of atheism is not merely an intellectual shift but an emotional rejection of the chaos associated with religious identity. The “Ex-Muslim” is often a refugee from the “War of the Sects.” The only way to win them back is to present a version of Islam that is cleansed of sectarian toxicity and aligned with the objective truths of science.

Leave a comment