Abstract:

In 1759, a remarkable incident in Sweden challenged the Enlightenment’s strict reliance on reason over mysticism. Emanuel Swedenborg, a distinguished scientist-turned-mystic, allegedly perceived a distant fire in Stockholm while attending a dinner 400 kilometers away in Gothenburg. This case – bolstered by multiple eyewitness testimonies and later investigated by philosopher Immanuel Kant – is often cited as a classic example of crisis telepathy or clairvoyance. This analysis recounts the incident with evidence from contemporary accounts and Kant’s own correspondence, then examines critical perspectives. The evidence, including Kant’s confirmation of details from official reports, suggests Swedenborg’s report uncannily matched reality. Yet, skeptics question the story’s verifiability and caution against drawing broad conclusions from a single anecdote. In an age championing rationality, the Swedenborg incident remains an intriguing anomaly – a clash between empirical reason and the mysterious capabilities of the human mind. The epilogue reflects on how this event straddles the Enlightenment’s Age of Reason and enduring questions about human consciousness.

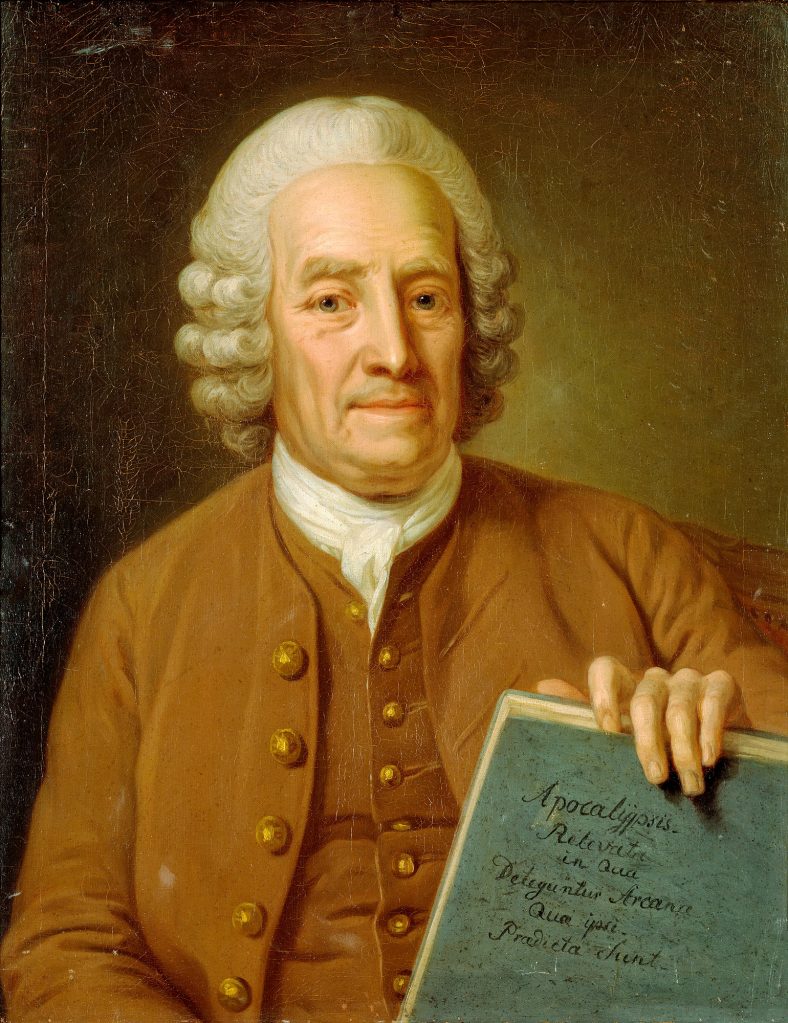

Enlightenment Context and Swedenborg’s Reputation

The mid-18th century was the Age of Enlightenment, a period that prized reason, science, and skepticism over superstition. It was therefore especially striking that one of the era’s most credible reports of clairvoyance came from Sweden, a center of learning. The protagonist, Emanuel Swedenborg, was no obscure occultist; he was a renowned intellectual and polymath. Swedenborg had served as an assessor on the Swedish Board of Mines (Bergskollegium) and earned esteem as an engineer, metallurgist, anatomist, astronomer, and theologian. One contemporary source notes that he was “a man of the world, a scientist and highly respected authority on metallurgy, a lecturer on economics, and an occasional lobbyist for political causes”, which meant “his psychic phenomena gained more credibility than they would for someone less reputable.” In other words, Swedenborg’s solid scientific reputation inclined his educated peers to take his paranormal claims seriously. Even the critical philosopher Immanuel Kant initially showed interest in Swedenborg’s stories; Kant ordered copies of Swedenborg’s hefty theological works and in correspondence described him as “reasonable, agreeable, remarkable and sincere”, a learned and “miraculous” gifted man. Thus, the stage was set for a dramatic incident that would test the boundaries between Enlightenment rationalism and unexplained phenomena.

The 1759 Stockholm Fire: Swedenborg’s Vision at a Distance

On Saturday, July 19, 1759, Swedenborg was attending an evening soiree at the Gothenburg home of William Castel, a prominent merchant. The gathering was cordial, with about fifteen guests dining together. Swedenborg had just returned from a trip to England earlier that day. Around 6:00 P.M., as dinner progressed, Swedenborg suddenly grew agitated. Without warning, he excused himself from the table and rushed outside. Moments later he returned ashen-faced and alarmed, startling the company with an urgent announcement: Stockholm was on fire.

Gothenburg and Stockholm are about 400 km (~250 miles) apart – a journey of several days by 18th-century standards – so the guests were baffled by how Swedenborg could possibly know of a fire in the distant capital. But Swedenborg was adamant. He gave specific details: a “dangerous fire had just broken out in Stockholm, at the Södermalm” (the southern district of the city) and was spreading rapidly. He was especially distressed because Södermalm was the neighborhood of his own residence. Sweating and pacing, Swedenborg reported that the house of one of his friends was already in ashes, consumed by the flames, and that his own house was in grave danger. His obvious distress and the precision of his descriptions stunned the dinner guests. One account notes, “He was restless and went out often”, as if periodically checking on the fire’s progress via an inner vision. The party host and other witnesses could only listen in anxious disbelief.

For the next two hours, Swedenborg periodically interrupted the uneasy gathering with updates on the conflagration. Sometime after 8:00 P.M., he left the house again for a few minutes. When Swedenborg returned this time, his mood had dramatically shifted – he appeared relieved and overjoyed. With a prayer of thanks, he proclaimed: “Thank God! The fire is extinguished – the third door from my house.” In other words, the fire had stopped just three buildings away from his own property on Stockholm’s Hornsgatan street. Having delivered this climax to his strange vigil, Swedenborg could finally calm himself.

The guests in Gothenburg were astonished, as word of Swedenborg’s pronouncements spread quickly through the city. Many feared it might be true and grew concerned for friends or family in Stockholm. The idea that a raging fire in the capital could be psychically “seen” from hundreds of miles away seemed incredible, yet Swedenborg’s emotion and specificity were hard to dismiss. That same Saturday evening, Governor Carl Höpken (the provincial governor of Gothenburg) learned of Swedenborg’s disturbing claims. Sensing the anxiety it was causing, the Governor took the report seriously enough to consider an official inquiry.

Verification: Messages from Stockholm and Kant’s Inquiry

By Sunday morning (July 20), news of Swedenborg’s vision had so permeated Gothenburg that Governor Höpken summoned Swedenborg for questioning. The Governor asked Swedenborg to recount what he “saw” in detail. Swedenborg precisely described the fire’s timeline and location, including “how it had begun, in what manner it had ceased, and how long it had continued.” He even identified the street (Södermalm) and how far the flames had reached (to the third door from his own house). These specifics were noted by the Governor, albeit with some skepticism. No conventional news could have arrived from Stockholm so quickly – at least not until official couriers completed the arduous overland journey.

Over the next two days, confirmation of Swedenborg’s remote vision arrived via normal channels, dramatically vindicating his account. On Monday evening, July 21, a messenger from Stockholm finally reached Gothenburg, bearing letters and dispatches. This rider had been “despatched by the Board of Trade during the time of the fire”. The letters he carried described the Stockholm blaze in “precisely the manner stated by Swedenborg.” The correspondence confirmed that a fire had indeed broken out in Stockholm on July 19, devastating a section of Södermalm. Even more astonishing, the reports matched Swedenborg’s story down to fine details – including the location where the fire was halted. On Tuesday morning (July 22), a royal courier arrived at Governor Höpken’s residence with the official government report of the disaster. This formal report itemized the damage: roughly “20 blocks with about 300 houses” were reduced to ashes and some 2,000 people left homeless, though casualties were minimal. Crucially, it also confirmed the fire’s timing and its geographical limit. The flames had started around 6:00 P.M. on July 19 and were contained by 8:00 P.M. the same night – exactly when Swedenborg announced their cessation – and indeed the conflagration was stopped just a few doors away from Swedenborg’s own house on Hornsgatan. As one summary puts it, “the fire was extinguished at eight o’clock… not in the least differing from that which Swedenborg had given at the very time when it happened”. In other words, every particular Swedenborg had declared in Gothenburg was verified by the official news from Stockholm.

Evidence from Kant’s Letter: The most famous verification of this incident comes from Immanuel Kant, who was intensely curious about Swedenborg’s psychic claims. In 1763, Kant wrote a detailed letter to a noblewoman, Charlotte von Knobloch, describing the Swedenborg fire story after investigating it. Kant had arranged for his trusted English friend Joseph Green (often spelled “Green” or “Greene”) to interview eyewitnesses in both Stockholm and Gothenburg. Green was uniquely qualified as an investigator – Kant considered him a model of clear-headed, unbiased judgment. According to Kant, Mr. Green spoke with “the most respectable” citizens in Gothenburg, and because “only a very short time has elapsed since 1759, most of the inhabitants are still alive who were eyewitnesses of the occurrence.” The results of Green’s inquiry were unequivocal: all sources concurred that Swedenborg had described the Stockholm fire in real-time, exactly as later confirmed.

Kant recounts the episode as follows (in a passage often quoted as the definitive account of the incident):

- “[In] 1759, towards the end of July, on Saturday at four o’clock p.m., Swedenborg arrived at Gothenburg from England, when Mr. William Castel invited him to his house together with a party of fifteen persons. About six o’clock, Swedenborg went out, and returned to the company quite pale and alarmed. He said that a dangerous fire had just broken out in Stockholm, on Södermalm (where his house was), and that it was spreading very fast. … He said that the house of one of his friends, whom he named, was already in ashes, and that his own was in danger. At eight o’clock, after he had been out again, he joyfully exclaimed, ‘Thank God! the fire is extinguished, the third door from my house.‘ This news occasioned great commotion throughout the whole city, but particularly amongst the company in which he was. It was announced to the Governor the same evening.”

- “On Sunday morning, Swedenborg was summoned to the Governor, who questioned him concerning the disaster. Swedenborg described the fire precisely – how it had begun, in what manner it had ceased, and how long it had continued. … On Monday evening a messenger arrived at Gothenburg, who was despatched by the Board of Trade during the time of the fire. In the letters brought by him, the fire was described precisely in the manner stated by Swedenborg. On Tuesday morning the royal courier arrived at the Governor’s, with the melancholy intelligence of the fire, of the loss which it had occasioned, and of the houses it had damaged and ruined, not in the least differing from that which Swedenborg had given at the very time when it happened, for the fire was extinguished at eight o’clock.”

Kant, a man known for his critical rigor, found the testimony of Swedenborg’s startling vision difficult to refute. In his letter, after relaying the story, Kant pointedly asks: “What can be brought forward against the authenticity of this occurrence (the conflagration in Stockholm)?”. He emphasizes that his informant (Green) “has examined all, not only in Stockholm, but also, about two months ago, in Gothenburg, where he… obtained the most authentic and complete information”, with numerous living witnesses confirming the event. Kant then concludes that “The following occurrence appears to me to have the greatest weight of proof, and to place the assertion respecting Swedenborg’s extraordinary gift beyond all possibility of doubt.” Such strong words from a famously skeptical philosopher lend substantial credence to the Swedenborg incident. Indeed, Kant openly states that the evidence “places the assertion [of Swedenborg’s clairvoyance] beyond all possibility of doubt” – a remarkable admission.

It bears noting that outside Sweden, this Great Stockholm Fire of 1759 is largely remembered because of Swedenborg’s reported vision. Modern historical accounts routinely mention the anecdote. For instance, a detailed history of Stockholm’s fires observes: “Outside Sweden, this fire is most famous due to an occult anecdote that claims… Emanuel Swedenborg, through a sort of clairvoyance, ‘saw’ the fire from Gothenburg.”. In Swedenborg’s own biographical lore, it remains one of the *“three chief stories on which his reputation for clairvoyance rests,” alongside a reputed message from a dead ambassador about a lost receipt, and a secret told to Queen Louisa Ulrika. That Swedenborg’s fire vision is “well-documented” and occurred in front of many reputable witnesses has led it to be characterized as “one of the best authenticated instances of telepathy in history.” Contemporary writers stressed that Swedenborg’s standing as a serious scholar made the case all the more compelling. Immanuel Kant himself – while deeply critical of metaphysical mysticism – conceded that the “memorable occurrence” of the Stockholm fire vision had “the greatest part of the inhabitants [of Gothenburg], who are still alive, [as] witnesses to the memorable occurrence.”. In short, evidence from multiple sources – private letters, official reports, and numerous eyewitnesses – converged to affirm that Swedenborg somehow accurately perceived a distant crisis in real time.

Interpretation: Crisis Telepathy or Coincidence?

This extraordinary case has invited many interpretations over the past two centuries. Parapsychologists view the Swedenborg incident as a classic example of spontaneous telepathy or clairvoyance under crisis conditions – sometimes termed “crisis telepathy.” In the late 19th century, researchers Edmund Gurney and Frederic W. H. Myers of the Society for Psychical Research studied hundreds of instances of apparent telepathic impressions coinciding with distant emergencies. They found that often a person experiences a vivid vision or sense of a loved one’s distress at the very moment of that loved one’s death or crisis – far beyond the reach of normal communication. The Swedenborg fire neatly fits this pattern of a high-emotion event triggering a veridical psychic experience. Here, the “sender” (if one speculates telepathically) could be the collective terror of Stockholm’s inhabitants or Swedenborg’s own intense emotional investment (his home and writings were threatened), broadcasting a sort of psychic SOS. The notion is that extreme emotional or life-threatening events create a kind of “signal flare” that certain sensitive individuals pick up, even at great distances. As one review of psychic phenomena notes, “there are, in credible reports, many cases where a person has a ‘vision’ of a distant disaster or death later confirmed to be true, with no normal way to know it – far beyond chance coincidence.” Early psychical researchers dubbed these “veridical hallucinations”, meaning the percipient’s vision, though appearing like a hallucination, corresponds to real external events. Notably, an extensive “Census of Hallucinations” published in 1894 (analyzing 17,000 persons) found that such crisis visions occurred far more frequently than chance would allow, particularly involving death or danger to someone emotionally close to the percipient.

Given Swedenborg’s report involved a major catastrophe and personal stakes, later writers speculated that his case illustrates this “crisis telepathy” mechanism. Psychical researcher Frank Podmore suggested Swedenborg’s anguish for his city and home might have attuned him to the disaster psychically, a hypothesis consistent with other cases of “collective unconscious alarm.” In Phantasms of the Living (1886), Gurney analyzed Swedenborg’s fire vision alongside similar phenomena and noted it “carries us beyond the limits of our assured knowledge,” yet he saw it as part of a continuum of documented telepathic cases. In modern terms, one might say Swedenborg experienced a form of remote viewing induced by acute emotional resonance with events in Stockholm.

It is important to emphasize that Swedenborg himself attributed his knowledge to spiritual means, not any form of guessing or inference. By the late 1750s, Swedenborg believed he had direct access to information from the spiritual world. He claimed that in states of prayer or vision he conversed with spirits and even angels, who could reveal things beyond the reach of the physical senses. According to Kant’s letter, Swedenborg “told [Kant’s friend] without reserve that God had accorded him this remarkable gift of communicating with departed souls at his pleasure”, and that he intended to publish an explanation of these abilities. While the Stockholm fire example did not involve conversing with the dead, Swedenborg might have viewed it as a demonstration of his God-given “inner sight.” In his theological writings, Swedenborg suggested that the soul can sometimes perceive distant events when in an exalted state, freed from the limits of space and time – essentially describing clairvoyance as a spiritual phenomenon.

Contemporaries had various opinions. Some devout admirers saw the incident as proof of Swedenborg’s divine inspiration, a sign that he truly was in touch with higher planes of knowledge. They pointed out that such feats were consistent with biblical examples of prophets perceiving distant or future events. Others, more secular, considered telepathy a natural (if rare) faculty – perhaps an undiscovered mental ability that a genius like Swedenborg inadvertently tapped. Indeed, Kant himself, despite his official skepticism, mused in private whether “there might be some unknown faculty in the human mind to receive information through other than the known senses,” given the strength of cases like Swedenborg’s. This speculation would later feed into serious research on telepathy and clairvoyance in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Critical Perspectives and Skepticism

Despite the impressive testimonies, not everyone has been convinced that Swedenborg’s Gothenburg vision was truly paranormal. Skeptics have raised several objections and alternative viewpoints over the years:

- Anecdotal Nature & Lack of Contemporary Documentation: Critics note that the story rests on eyewitness accounts and second-hand reports, rather than any direct documentation from 1759. We have Kant’s letter (written in 1763) detailing what he learned from witnesses, but no newspaper articles or official records from 1759 mention Swedenborg’s feat at the time (understandably, since such an occurrence would have been difficult to officially report). Thus, the evidence, while strong as oral history, is still hearsay to some degree. The principal witnesses in Gothenburg did not, as far as is known, write their own accounts – their testimony comes via Kant’s investigator Green. A modern skeptic might question whether memories could have been mistaken or exaggerated in the retelling. Could the Gothenburg guests have misremembered the exact phrasing or timing of Swedenborg’s remarks after being influenced by subsequent news? The International Skeptics Forum, for instance, has members arguing that “we only know this happened because Swedenborg (and his followers) said it did… Just because no one at the time said otherwise doesn’t make it true.”. This stance highlights that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence – and some feel the evidence here, while intriguing, doesn’t meet the scientific standard of documentation or replicability.

- Coincidence or Prior Knowledge: The probability of randomly guessing a major fire with such accuracy is infinitesimal – which is why most skeptics don’t assert it was mere luck. However, a few have wondered if some information could have reached Gothenburg by normal means slightly before the official couriers. For example, could a fast ship or a rider from halfway (if the fire had started earlier than reported) have arrived and privately informed Swedenborg? This seems highly implausible given the timeline (two hours is far too short for any 18th-century messenger over that distance), and no evidence of such a message exists. The official records confirm that organized communication left Stockholm during the fire (via the Board of Trade courier) and took two days to reach Gothenburg. Thus, normal channels were far too slow to account for Swedenborg’s knowledge. A related idea is that Swedenborg might have heard about previous fires or was making a educated “premonition” based on conditions (Stockholm was under a drought and had a history of fires). But even if he had general worries, it does not explain the precise details he gave (friend’s house, exact timing of extinguishing). The coincidence theory strains under the specificity of the case.

- Psychological Factors: Some skeptics propose that Swedenborg could have experienced a hallucination or vivid dream-like vision born of anxiety. If, for instance, he had been preoccupied with fear for Stockholm (his entire library and work were at home), it’s conceivable he might have hallucinated a scenario of fire. By sheer chance, parts of that hallucination may have aligned with reality. While not impossible, this stretches credibility – essentially requiring one to believe in an astounding coincidence that his “fantasy” matched real events to the minute. Nonetheless, psychologists caution that human perception and memory are fallible. Swedenborg’s prior intensive mystical practices and self-induced trances (he regularly engaged in spiritual exercises and dream journaling) could have primed him for visions. A biographer comments that even if “overwhelming testimony to Swedenborg’s truthfulness” exists, “even the most truthful can be self-deceived.” In other words, Swedenborg might sincerely have believed he saw the fire psychically, but a hardened skeptic might label it “a self-fulfilling fantasy later corroborated by happenstance.” This, however, does not account for how the “fantasy” anticipated reality so well.

- Immanuel Kant’s Public Reversal: A striking element in the aftermath is that Immanuel Kant, despite privately verifying Swedenborg’s powers, later became an open skeptic of Swedenborg’s claims. In 1766, Kant anonymously published Träume eines Geistersehers (Dreams of a Spirit-Seer)_, a sarcastic critique of Swedenborgian mysticism. In this treatise, Kant systematically ridiculed Swedenborg’s reports of conversing with spirits, calling him a “visionary” engaging in fantasy. Kant even referred to Swedenborg as “an arch-spook hunter” with no proof for his ghostly commerce. He portrayed Swedenborg’s spiritual experiences as illusory and unworthy of philosophical credence. This public dismissal has fueled skeptics: if even Kant ultimately disavowed Swedenborg, perhaps the 1759 incident did not seem so ironclad to him after all. However, it is well-documented that Kant’s criticism in Dreams of a Spirit-Seer was motivated partly by self-preservation – he was wary of being associated with supernatural ideas and attracting ridicule in academic circles. In private letters, Kant hinted that his published skepticism was “clothed in irony” and that he still found Swedenborg’s accounts noteworthy. Nonetheless, the fact remains that no leading Enlightenment scholar publicly championed the Swedenborg case as proof of psychic phenomena. Kant’s ambivalent stance often serves as a caution: a rigorous thinker can find an anecdote convincing on a personal level, yet still refrain from accepting it as scientific evidence.

- No Wider Scientific Impact: From a scientific perspective, the Swedenborg incident did not lead to any testable theory or repeatable demonstration. It stands isolated – spectacular but singular. The Enlightenment demand for reproducibility could not be met; Swedenborg’s gift (if real) was not something that could be summoned at will in controlled conditions. As a result, mainstream science largely ignored or quietly marveled at the story without integrating it into any empirical framework. To skeptics, this suggests that the event, while intriguing, holds little value in proving anything about nature. It could forever remain an anecdote, one of those peculiar historical footnotes rather than a foundation for science. Indeed, the incident often ends up in collections of “unexplained events” rather than physics textbooks.

In summary, critical analysis of the Swedenborg fire incident acknowledges the honesty and consistency of the witnesses, but cautions that extraordinary claims need more than uncorroborated testimony. As one skeptic quipped regarding Swedenborg, “Did any of this ever actually happen?” – highlighting the ultimate impossibility of verification beyond the word of those present. While no normal explanation fits the facts as reported, the lack of a normal explanation does not automatically confirm a paranormal one. Thus, the Swedenborg incident remains a kind of Rorschach test: believers in the paranormal see it as compelling evidence of clairvoyance, whereas disbelievers see it as an intriguing story that falls short of proof.

Epilogue: Clairvoyance in the Age of Reason

The Swedenborg Incident occupies a fascinating place in intellectual history, sitting at the crossroads of Enlightenment rationality and the enduring allure of the mysterious. It occurred at a time when educated society was determined to banish superstition and embrace scientific explanation, yet here was a case that reason alone could not readily explain. The very credibility of the witnesses and the precision of the fulfilled details forced even skeptics like Kant to grapple with the limits of what was deemed possible. In an age “enlightened” by Voltaire, Hume, and Diderot, the story of a respected scientist accurately “seeing” a distant disaster challenged the tidy separation between natural law and spiritual phenomena.

For Swedenborg himself, the incident only reinforced his dual identity as scientist and seer – a man equally at home discussing mining engineering and conversing with angels. He became, in a sense, a symbol of the Enlightenment’s forgotten possibilities: that there might be “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy,” to quote Shakespeare. His fire vision suggests that human consciousness may have latent capacities not fully understood, a notion both exhilarating and unsettling to the Enlightenment mind. Little wonder that later Romantics and occultists revered Swedenborg; William Blake, for instance, was profoundly influenced by Swedenborg’s mingling of reason and vision.

In the broader sweep of history, the Swedenborg incident has been a touchstone for debate about the paranormal. It has been cited in countless books on psychic phenomena as a prime historical case of telepathy or clairvoyance, yet it also appears in skeptical critiques as an example of the anecdotal nature of such claims. To this day, it invites us to ask: Can an instance of apparent clairvoyance be accepted as real if it cannot be scientifically reproduced? The Enlightenment would answer no, favoring skepticism until proof is overwhelming. But the human psyche, even in that “Age of Reason,” was captivated by the possibility that Swedenborg’s mind transcended physical barriers in a moment of crisis.

Thus, the legacy of the Swedenborg incident is two-fold. On one hand, it stands as a well-attested mystery that continues to intrigue open-minded scholars and parapsychologists – a reminder that our understanding of consciousness is incomplete. On the other hand, it serves as a cautionary tale in the annals of reason: even the brightest figures (like Kant) can be tempted by tales of the extraordinary, and even the most extraordinary tales remain inconclusive without broader evidence. The Age of Reason did not wholly banish wonder; instead, stories like Swedenborg’s fire vision show how wonder persisted, clandestinely, in drawing rooms and learned correspondence.

In the end, The Swedenborg Incident invites each generation to balance healthy skepticism with an openness to the unexplained. It asks whether phenomena on the fringes of understanding should be dismissed outright, or examined as potential clues to capacities of the mind. Clairvoyance in the Age of Reason was an anomaly, but also a beacon for those who believed that science had not yet charted all the realms of human experience. The story survives, much like the smoldering embers of that July 1759 fire, as a glowing reminder that even in an era of light, shadows of mystery lingered – challenging the thinkers of then and now to enlarge the circle of human knowledge to accommodate the seemingly impossible.

Sources:

- Immanuel Kant (translated by Emanuel F. Goerwitz), Dreams of a Spirit-Seer – Appendix, Letter of Kant to Charlotte von Knobloch (August 1763). Wikisource. (Kant’s first-hand summary of Swedenborg’s 1759 fire vision and its confirmation.)

- Inge Jonsson, Emanuel Swedenborg, Scientist and Mystic (Chapter 15). Wikisource. (Detailed account of the incident as investigated by Kant’s friend; includes direct quotes from Kant’s report.)

- “Fire Alarm.” Futility Closet (Jan 6, 2011). (Brief retelling of the Swedenborg fire anecdote with Kant’s famous quote on the authenticity of the occurrence.)

- “Great Stockholm Fire of 1759.” Wikipedia. (Historical context of the fire; notes Swedenborg’s involvement and that the fire indeed stopped three houses from his home.)

- “Historical Fires of Stockholm.” Wikipedia. (Confirms the extent of the 1759 Mariabranden fire and the anecdote’s fame outside Sweden; clarifies date issues.)

- Encyclopedic Article: “Psychical Research.” Theosophy World. (Highlights Swedenborg’s case as well-authenticated and emphasizes his credibility as a scientist which gave the clairvoyance report weight.)

- Emanuel Swedenborg – Biography. Wikipedia. (Describes Kant’s interactions with Swedenborg – initial admiration and later publication of Dreams of a Spirit-Seer criticizing him.)

- Forum discussion on Swedenborg’s fire vision. International Skeptics Forum. (Illustrates modern skeptical viewpoints questioning the proof and noting Kant’s public conclusion that Swedenborg’s visions were illusory.)

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment