Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

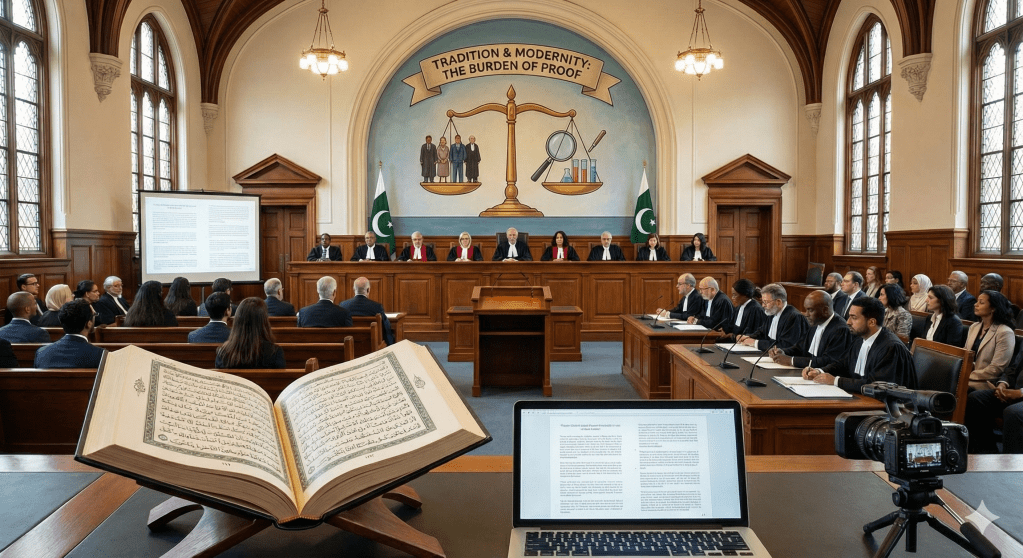

Case No. 9 is a groundbreaking Pakistani Urdu drama that not only delivers a gripping courtroom story but also challenges long-held societal and legal notions about rape and justice. This comprehensive review outlines the drama’s plot and themes – from its portrayal of a rape survivor’s fight for justice to its fearless critique of victim-blaming culture – and connects them with a re-examination of Islamic legal principles. In particular, the drama’s story underscores why the Quran’s 7th-century requirement of four eyewitnesses for adultery cases was a context-specific safeguard against false accusations, and how in the 21st century, advances in forensic science and modern judiciary practices fulfill the essence of that rule without literal adherence to it. We argue that what was once an absolute eyewitness requirement in an age with no forensic tools is today met by clear and convincing evidence – DNA, medical reports, digital recordings – which act as “silent witnesses.” The drama’s narrative, combined with Quranic context, illustrates that the true Quranic intent was to ensure justice and protect the innocent, a goal that remains paramount even as the methods of proof have evolved. In essence, the four-witness standard lives on as the principle of requiring strong evidence – not necessarily four pairs of eyes – to establish guilt in cases of adultery, rape, or other serious allegations.

Case No. 9: Plot Overview and Key Themes

Harrowing Crime and the Quest for Justice: Case No. 9 follows the harrowing journey of Sehar Moazzam (played by Saba Qamar), a confident professional whose life is upended by a brutal crime. Her boss, Kamran (Faysal Quraishi), deceitfully lures her to his home under false pretenses and then rapes her. A colleague, Rohit (Junaid Khan), sensing something amiss, arrives to help – but by the time he reaches Kamran’s house, the unthinkable has already happened. Rohit rescues a traumatized Sehar and rushes her to safety. This incident sets in motion a gripping courtroom drama that shines a light on the many obstacles a rape survivor faces in seeking justice.

Systemic Obstacles and Societal Stigma: In the immediate aftermath, Sehar’s struggle is not just with her assailant but with the very system that should protect her. Under family pressure and fearing “honor” issues, she is initially prevented from undergoing a timely medico-legal examination – a decision that speaks volumes about how victims are often silenced by stigma. It takes a full week for Sehar to summon the courage (and overcome familial opposition) to file an FIR (First Information Report) with the police. By then, crucial physical evidence has likely deteriorated, illustrating how societal taboos can actively undermine justice. To make matters worse, the officer in charge, Inspector Shafeeq (Mirza Gohar Rasheed), turns out to be corrupt and is bribed by Kamran to sabotage the case. Instead of aiding the victim, the law enforcement aligns with the perpetrator – a grim reminder of the real-world power dynamics that often protect the influential.

Allies and Adversaries in Court: Despite these setbacks, Sehar finds steadfast allies. Her friend’s wife, Manisha (Naveen Waqar), is a passionate lawyer who steps up to represent her. Manisha becomes Sehar’s rock and legal counsel, determined to fight the case in court. To bolster the prosecution, another attorney, Beenish Ali (Aamina Sheikh), joins as a special prosecutor who will stop at nothing to see justice served. On the opposing side stands Kamran’s defense team, including a shrewd lawyer named Bukhari (Noor-ul-Hasan), who employs every trick to discredit Sehar. What begins as a personal tragedy for Sehar soon unfolds in the courtroom as a scathing commentary on societal hypocrisy, where a victim’s character and past are dissected far more than the crime itself. The stage is set for a battle not just between a victim and her rapist, but between truth and prejudice.

Strong Women Shattering Stereotypes: One of the most refreshing aspects of Case No. 9 is its portrayal of women. Nearly all the female characters in the play are women of substance – strong, principled, and unafraid to stand up for what is right. Sehar herself embodies quiet resilience and courage, refusing to be shamed into silence. Her mother (played by Hina Khawaja Bayat) supports her unconditionally, defying the typical trope of elders prioritizing “family honor” over justice. Manisha, the lawyer, is fierce and intelligent, using her legal acumen to dismantle false narratives about rape. Even Kiran (Rushna Khan) – who is Kamran’s own wife – emerges as a formidable character; when evidence of her husband’s monstrosity becomes undeniable, Kiran makes the bold decision to leave him, despite the personal cost of ending her marriage. This is a significant departure from the submissive, “stand-by-your-man” archetype traditionally expected of South Asian wives. Together, these women in Case No. 9 redefine the archetype of the Pakistani drama heroine, showing strength with empathy, and loyalty only to truth and justice.

Villainy, Manipulation, and Moral Complexity: In contrast, many of the male characters are portrayed with unflinching honesty as deeply flawed or morally weak. Kamran, the rapist, is a powerful businessman whose ego cannot tolerate a woman’s refusal. Winning the case becomes an obsession for him – not just to escape punishment, but to “make an example” of Sehar and any woman who dares say “no” to a man like him. He is so consumed by pride and malice that even after Kiran leaves him and his reputation is in tatters, he doubles down on his cruelty. The drama makes a poignant observation: no matter what happens in court, Kamran has already lost. If he wins the case through lies or technicalities, his social reputation is ruined; if he loses, his career and freedom are gone. Other men in the story face their own demons: Rohit (the colleague who saved Sehar) is revealed to be constrained by a dark secret from his past – a “blasphemy” accusation incident – which Kamran uses to blackmail him into not testifying in court about what he witnessed. This subplot is especially bold, hinting at Pakistan’s controversial blasphemy laws and how they can be misused to trap people. The inclusion of this angle adds layers of moral complexity: even decent individuals like Rohit can be rendered helpless in the face of draconian laws and manipulative power plays. In Case No. 9, there are no easy choices for anyone – every character, whether virtuous or villainous, is fighting some inner battle or caught in a web of consequences. This nuanced characterization keeps the drama realistic and emotionally charged.

A Courtroom Drama with a Social Message: As the trial unfolds, Case No. 9 transcends mere entertainment and becomes a powerful public service message about rape and justice. The courtroom scenes are electrifying and unprecedented in Pakistani television for their frankness. In one standout episode (Episode 17, which many viewers hailed as historic), prosecutor Beenish Ali (Aamina Sheikh) delivers a tour-de-force courtroom argument that systematically debunks the misogynistic myths surrounding rape. She cites hard facts and statistics about sexual violence in Pakistan – noting, for instance, that eight children are sexually abused in the country every day and that women from all walks of life face harassment daily. With surgical precision, Beenish contrasts truth vs. stereotypes and facts vs. false cultural narratives, leaving even the crafty defense lawyer Bukhari unable to counter her data-driven arguments. The drama doesn’t shy away from taboo topics: it directly addresses marital rape, asserting that “no means no” even within marriage – a bold stance in a society where many orthodox voices have long denied the very concept of marital rape. It also tackles the “character assassination” often aimed at women who come forward: Beenish references a landmark legal verdict establishing that a woman’s past or sexual history cannot be used against her in a rape trial. It doesn’t matter if the woman is a virgin, divorced, or married – what matters is whether she was raped or not. This pivotal moment in the drama educates the audience that under Pakistani law today, a survivor’s character is not on trial, only the actions of the accused are.. In another example of life influencing art, the show celebrates the recent real-world legal progress: it lauds Justice Ayesha Malik – a real-life judge of Pakistan’s Supreme Court – for her role in outlawing the degrading “virginity tests” that used to be inflicted on rape survivors. (In 2021, Justice Malik and the Lahore High Court declared the so-called “two-finger virginity test” unconstitutional and without medical basis, a fact directly woven into the drama’s dialogue to highlight how far the law has come in protecting victims’ dignity.)

Impact and Reception: The unflinching honesty of Case No. 9 has made it a national talking point. Viewers and critics have praised it for “saying things with such clarity and force that have never been said [on Pakistani TV] before”. Episode 17, in particular, is hailed as a game-changer that “made women feel empowered by law” – a depiction of a rape trial where the law, at least in the voice of Prosecutor Beenish, is squarely on the side of the victim and not the perpetrator. This is a dramatic shift in a media landscape where, not too many years ago, rape victims on screen were often shown as helpless, silenced, or even blamed. By contrast, Sehar’s story in Case No. 9 offers a ray of hope: it shows that if women band together, use the legal tools at their disposal, and refuse to bow to intimidation, justice can be pursued even against powerful men. The drama is careful not to paint an overly rosy picture – the conviction rate for rape remains dismally low, and the road to justice is fraught with hurdles – yet it dares to inspire. It sends a clear message that rape is a heinous crime, and survivors have every right to seek justice without shame. The show’s popularity (evidenced by high ratings and fervent social media discussions) is encouraging creators to venture into such “hitherto uncharted territory”, proving that audiences are ready for content that is both socially relevant and deeply engaging. Case No. 9 has truly “redefined the landscape of Pakistani dramas by shattering a number of stereotypes,” as one reviewer aptly noted. From strong female leads to calling out patriarchal customs, it has set a new benchmark that future dramas will likely be measured against.

Hope and Solidarity: As the series heads toward its climax, it emphasizes that the fight is larger than one woman’s case. In a poignant subplot, another woman who had been one of Kamran’s silent victims in the past reaches out to Sehar – she found the courage to come forward after seeing Sehar take a stand. This domino effect, where one voice emboldens another, is exactly what Pakistan’s #MeToo movement and activists have been striving for. The drama thus not only narrates a story but becomes part of a broader cultural conversation about women’s rights and solidarity. The depiction of Sehar embracing the term “rape survivor” (rather than “victim”) is deliberate and empowering. She refuses to see herself as defeated or tainted by the assault; instead, her survival and pursuit of justice become a badge of honor. In one cathartic dream sequence, Sehar even imagines herself standing up in the courtroom to directly confront Kamran – shedding the decorum and fear that have restrained her – and in that imagined moment she reclaims her power from him. It’s a brief fantasy, but it symbolizes her psychological journey from trauma towards healing. By the end, Case No. 9 assures viewers that hope is here to stay – hope for Sehar’s personal quest, and hope that a new era is dawning in which Pakistani women, armed with truth and the law, can stand up to those who wrong them.

The Four-Witness Rule in 7th-Century Islam: Context and Purpose

The drama’s narrative naturally leads to a discussion about evidence and justice – and this is where we connect to a famous Quranic injunction: the requirement of four eyewitnesses to prove sexual misconduct (particularly adultery or fornication). To modern ears, this rule sounds exceedingly strict – and it is. In fact, that was exactly the point. To understand why such a rule exists, we must travel back to 7th-century Arabia and examine the context in which these verses were revealed.

In an era with no forensic science, no surveillance cameras, and no modern investigative tools, a person’s word or eyewitness testimony was often the only type of evidence available. The Quran’s insistence on not one, not two, but four adult Muslim eyewitnesses for an adultery allegation was an almost insurmountable standard – a “nearly impossible” threshold except in the most extraordinary circumstances. This was deliberate. The Quran (Surah An-Nur, Chapter 24) introduced this rule after a notorious incident known as the Incident of al-Ifk (Slander), in which a false rumor of adultery was spread about Aisha, the Prophet Muhammad’s wife. Innocent of the accusation, Aisha suffered great distress until the Quran declared her innocence and, crucially, set stringent conditions for any future accusations of such nature. The revelation mandated that anyone accusing a chaste woman (or man) of adultery must produce four eyewitnesses to the act, otherwise the accuser themselves would face a punishment for slander (80 lashes). In essence, the Quran raised the bar of proof so high that it effectively shut the door on he-said/she-said slander.

Wise Purposes of a Strict Standard: Classical Islamic scholars never saw the four-witness rule as a mere “technicality” – they recognized it as a mechanism brimming with wisdom and higher intent. The harsh letter of the law was instituted for very compassionate reasons. Among the key purposes were:

- Protecting Honor and Privacy: By making it nearly impossible to publicly accuse someone of adultery without overwhelming proof, the Quran was shielding personal honor and the sanctity of the private sphere. In a society where a person’s (especially a woman’s) reputation could be destroyed by one malicious rumor, this high evidentiary bar acted as a merciful barrier. It discouraged prying into people’s private lives and spreading gossip. No one could lightly drag someone’s intimate affairs into the public eye; doing so without solid proof meant severe consequences for the accuser. In effect, the Quran said: better to let a possibly guilty person go unexposed than to destroy the life of an innocent through false accusations. This principle preserved social harmony and personal dignity, teaching the community that snooping and moral policing were not acceptable. (The Quran explicitly warns against tajassus, or intrusive spying on others’ private matters, in another verse – Quran 49:12 – further underscoring privacy as a value.)

- Deterring False Accusers: Hand-in-hand with protecting the innocent was the goal of deterring the mischief-makers. The Quran’s stipulated punishment for anyone who accuses someone of adultery without four witnesses – 80 lashes and permanent disqualification of their testimony – is extremely severe. This wasn’t meant to punish truthful victims; rather, it was targeting those who weaponize accusations to hurt others. The context of the rule’s revelation (defending Aisha against slander) makes it clear that its primary target is the false accuser. Classical jurists noted that this essentially nullified casual accusations. Unless a person was absolutely certain and had three other credible eyewitnesses, they would dare not level such a claim publicly, lest they themselves be branded a liar by law. In practice, this virtually eliminated the “court of public opinion” in cases of alleged sexual misconduct – you couldn’t publicly level such charges at all without incontrovertible proof. The result was a society where, ideally, people minded their own business regarding others’ private sins, and the threshold for ruining someone’s honor was appropriately sky-high.

- Upholding Moral Seriousness without Vigilantism: The four-witness rule strikes a balance between acknowledging adultery as a grave sin and preventing witch-hunts in the name of enforcing morality. Islam considers adultery a serious immorality, but by design, the Quranic legal system did not encourage people to go out seeking sinners to punish. In fact, by requiring four witnesses who saw the act in flagrante, it essentially implies that only blatantly public acts of adultery (practically an exhibitionist scenario) would meet the criteria. Anything done in private – even if morally wrong – was left to God’s judgment unless proven otherwise in an extremely transparent way. This teaches an important ethical lesson: do not spy on or pry into the private failings of others. The Prophet Muhammad reinforced this by advising people to cover up others’ faults rather than expose them. Thus, the law firmly reminded the community that maintaining public decency is important, but not at the cost of compassion and personal privacy. The high evidentiary bar curbed any zealots who might be tempted to turn into self-appointed morality police. By making legal prosecution so difficult, the Quran in effect said “yes, adultery is sinful, but that doesn’t mean you should go snooping around or hurling accusations; leave people’s hidden sins to God unless you have clear proof.” This was a check against vigilante justice and societal hysteria over sexual matters.

In summary, the spirit of the four-witness rule was to protect the innocent, deter the malicious, and promote a morally conscious but non-invasive society. It made sure that while adultery was formally condemned, prosecutions were exceedingly rare – thus upholding the ideal without creating a brutal inquisition. Notably, early Muslim authorities practiced what later scholars coined as “doubt canon” (shubha): they took every opportunity to avoid imposing the Quran’s harshest hudud punishments if there was any uncertainty. And given the evidentiary standards, there was almost always uncertainty. The law was severe on paper but merciful in practice – a duality that has been a hallmark of Islamic legal tradition.

Rape versus Adultery – A Critical Distinction: It is vital to highlight something that Case No. 9 implicitly screams through its storyline: rape is not the same as adultery. This might seem obvious, but in legal terms this distinction was blurred in some historical (and unfortunately some modern) applications of Islamic law. Classical Islamic jurisprudence, however, was clear on this point. The requirement of four witnesses was meant for consensual zina (adultery or fornication), not for rape (forced sexual assault). Rape, termed ightiṣāb in Arabic, was generally treated by classical scholars as a form of violent crime – akin to highway robbery or terrorism (ḥirābah) – because it is a forcible violation of an innocent person, involving coercion and violence. Thus, the mentality of jurists was entirely different when addressing rape: the victim of rape was not to be punished; rather, the rapist was seen as a threat to public safety, and the crime carried heavy penalties (even capital punishment in some cases) just like other violent crimes. For example, many jurists (notably in the Maliki school) held that a woman alleging rape is not required to produce four witnesses – expecting such evidence for a covert violent crime is both “absurd and cruel,” as one scholar put it. Instead, jurists historically accepted circumstantial evidence for rape: if a woman was found wounded or screaming for help (istighātha) at the time of the incident, or if she became pregnant and immediately claimed it was by rape, these were taken as supporting proofs of her claim. Importantly, no reputable classical Islamic authority ever stated that a rape victim must bring four witnesses to avoid punishment for adultery – that terrible notion was a result of later misunderstandings and misapplications by literalist courts, not the intent of the Sharia. Classical judges aimed to exonerate a credible rape victim, not punish her; if a woman cried rape, the default was to treat her as a victim unless evidence proved otherwise. They even ruled that pregnancy alone should not be taken as proof of consensual zina if the woman claims it was due to rape or coercion. All this underscores that the four-witness rule was never meant to apply to rape cases in the first place – its purpose was to govern allegations of consensual misconduct, whereas rape was categorized separately as a violent, prosecutable offense on par with brigandage.

From Four Eyewitnesses to Forensic Evidence: Adapting Justice in the 21st Century

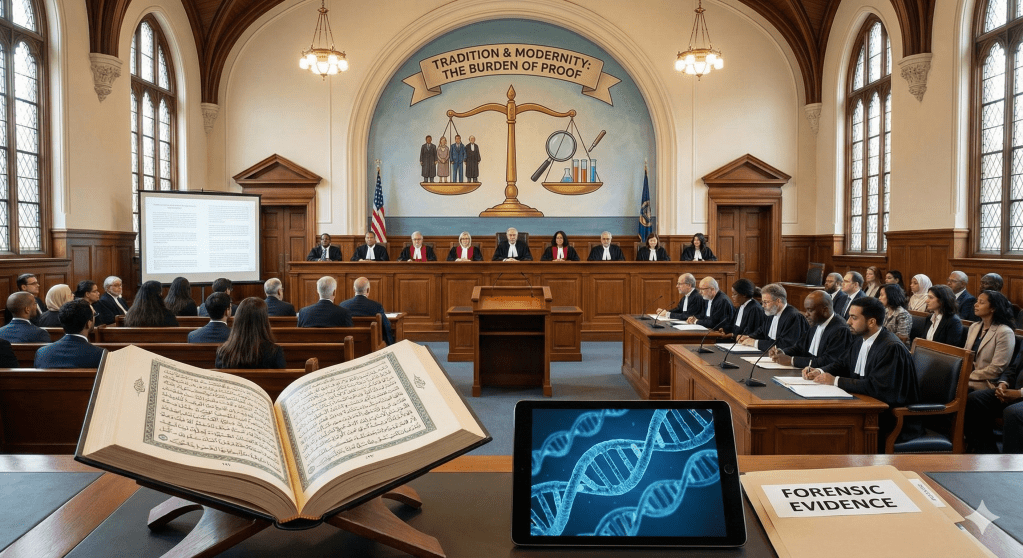

If the essence of the Quranic evidentiary principle is to establish truth and protect the innocent, then it stands to reason that as technology and science advance, the means of establishing truth can expand beyond human eyewitnesses. In Prophet Muhammad’s time, catching adulterers in the act with four witnesses was the only conceivable “proof beyond doubt.” Today, we have tools that the early Muslims could not even imagine, but which can, in many cases, provide evidence even more conclusive than eyewitness testimony.

Think of DNA fingerprinting: if a rape kit yields DNA that matches the accused with astronomical certainty, that is as good as – if not better than – seeing the act with one’s own eyes. Unlike human witnesses, DNA doesn’t lie, hold grudges, or forget details. Similarly, video surveillance cameras (CCTV), if available, can capture crimes in progress with an unblinking gaze. Digital records, such as phone location data or messages, can establish contacts and timelines that corroborate a victim’s story. Medical examinations can document injuries consistent with assault, and forensic psychologists can assess trauma. These are our era’s “silent witnesses.” They fulfill the same role that the four eyewitnesses were meant to fulfill in the 7th century – providing clear, convincing proof – but they do so with the sophistication of modern science.

Islamic thought has not been oblivious to these developments. Contemporary scholars and jurists have increasingly affirmed that the principle of the four-witness rule is proof beyond reasonable doubt, not a literal insistence on a particular quantity or type of evidence. If DNA, camera footage, or other forensic evidence yields certainty about a crime, then it effectively “fulfills the Quranic criterion of proof,” as modern Islamic legal analyses have noted. This isn’t a trivial modernization; it’s rooted in classical jurisprudence’s own flexibility. Historically, Muslim judges were guided by the Prophet’s saying “Avoid legal punishments (hudud) in cases of doubt”. In line with that, they were very cautious with evidence – but they also understood that any evidence that achieves certainty (or near-certainty) can be valid. For example, while the Quran requires witnesses for zina, if the accused voluntarily confessed clearly and repeatedly, that was taken as proof too. In our context, a DNA match or a video could be seen analogously as a kind of incontrovertible proof. It might not be eyeballs on the scene, but it’s evidence that can convince any reasonable person.

Crucially, this modern understanding prevents a distortion of justice. Insisting on exactly “four male eyewitnesses” in today’s world for crimes like rape would actually undermine justice rather than serve it. A renowned scholar famously warned against “worshipping the means at the expense of the ends,” saying that to rigidly maintain a procedure when it defeats the purpose of the law is to miss the point entirely. Nowhere is this more true than in rape cases. To demand four eyewitnesses for a rape is to misunderstand the Quran’s intent and to ignore the very values of justice and compassion that Islam came to uphold. The Quran’s intent was never to create an impossible hurdle for victims of violence – it was to protect the innocent (in that context, protect individuals, especially women, from false accusations of promiscuity). Applying the rule where it doesn’t belong (as in rape) “would shield perpetrators and harm victims, thus defeating the very aim of the law”, as one analysis put it bluntly. We saw this happen tragically in recent history: for a few decades, Pakistan (under a strict ordinance in 1979) misclassified rape under the same category as consensual zina, effectively requiring either four witnesses or a confession to prove it. The result? Countless rape victims were unable to get justice; some were even jailed as “adulteresses” because they couldn’t prove rape under that draconian standard. This legal regime was a gross distortion of Islamic teachings – one that thankfully was reformed in 2006 by Pakistan’s legislature, which moved rape back to the criminal penal code (distinct from zina) and allowed conviction on the basis of forensic and circumstantial evidence. Scholars near-unanimously supported this change, noting that Quran 24:4 was never meant for rape cases, and that justice demanded using any reliable proof to establish guilt. In other words, the Muslim consensus today (as it always was classically) is that a rapist can be punished as long as there is credible evidence – be it DNA, witnesses, medical reports, or a combination thereof – and that a victim’s inability to produce multiple eyewitnesses has no bearing on her honesty or entitlement to justice.

This evolution is in line with a broader principle: Islam’s laws are not arbitrary edicts frozen in time; they are tools to achieve justice, public welfare (maslaha), and moral order. When circumstances change and new tools emerge, Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) has mechanisms – like ijtihad (independent reasoning) and maqasid al-sharia (objectives of law) – to respond appropriately. The story portrayed in Case No. 9 illustrates this beautifully without even explicitly spelling it out. In the drama, we see that ultimately the case does not hinge on having four eyewitnesses (there were none, aside from the victim herself). Instead, progress comes from other forms of evidence and support: the testimonies of those who can corroborate parts of Sehar’s story, the inconsistencies in the defendant’s story, the moral force of expert witnesses or statistics that contextualize rape, and eventually additional victims coming forward to testify against the same man. While the show is fiction, these aspects mirror real-life trials in the modern world, where a combination of evidence – perhaps a medical report showing signs of assault, a torn piece of clothing, messages implying threats, and another victim’s testimony of a similar experience – together build a compelling case. This is the 21st-century equivalent of meeting the Quran’s evidentiary standard: not necessarily four ocular witnesses to the act, but a preponderance of clear evidence that leaves little room for doubt. The outcome is that the guilty can be punished with a clean conscience, and the innocent are protected from wrongful punishment.

It’s worth noting, too, that applying the essence of the four-witness rule today means not just using new types of evidence to prove guilt, but also maintaining the Quranic spirit of mercy wherever doubt exists. Just as classical jurists would rather drop a case than risk punishing an innocent person, modern law (at its best) follows the standard of “innocent until proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt.” That is essentially a secular phrasing of the Islamic principle that hudud punishments should be averted by even a shred of doubt. Therefore, upholding the four-witness rule in essence today means we insist on high standards of proof and due process. We reject whimsical allegations and trial by media or rumor – just as the Quranic verses aimed to quash gossip and unverified claims. In spirit, we are being very Quranic when we demand solid evidence like forensic proof, corroborating witnesses, credible testimony, and logical consistency in any case of adultery, rape, or serious moral crimes. We are carrying forward the intent of protecting individuals from false charges and ensuring that only the truly guilty are held accountable.

Epilogue: Bridging the 7th Century and the 21st – Justice with Compassion

In the final analysis, Case No. 9 is more than just a TV drama – it is a reflection of a society in transition, grappling with the collision of old norms and new values. Its resonance with audiences indicates a collective readiness to confront uncomfortable truths and to reform what must be reformed. The show’s courageous exploration of themes like rape, marital consent, and women’s autonomy is, in its own way, part of the ijtihad (intellectual striving) of our times – questioning harmful traditions and reaffirming moral truths. It reminds us that Islam’s core values of justice, mercy, and human dignity are not relics of the past, but living principles that demand fresh expression in every age.

Likewise, the Quran, when read with understanding, is not at odds with modern concepts of justice – on the contrary, it anticipated them in a profound way. The requirement of four witnesses was essentially a beacon of due process ahead of its time, a guarantee that people’s lives and honor would not be ruined by flimsy accusations. Today, we uphold that same beacon when we say no one should be convicted without solid evidence. The form has changed – forensic labs have replaced eyewitnesses in many scenarios – but the light is the same. Our challenge, as believers in the 21st century, is to ensure that the light of justice is not extinguished by a rigid clinging to the form that carried it in the 7th century. If the form (literal four witnesses) no longer serves the purpose (establishing truth and deterring falsehood), we are not betraying scripture by adapting; we are in fact being true to its deepest intent.

In the epilogue of Case No. 9, we imagine Sehar standing tall – whether the court verdict favored her or not – because she has reclaimed her voice and dignity. In a broader sense, this is the vision for all of us: to stand on the shoulders of our spiritual and legal tradition, not beneath its feet. The Quran did not come to oppress or silence the vulnerable; it came as a mercy to uplift them. Sometimes, mercy lies in strictness (as in the strictness of requiring four witnesses to prevent abuse of the law), and sometimes mercy lies in flexibility (as in adapting evidentiary requirements to new knowledge). Justice in Islam has always been a dance between letter and spirit, where the letter guards the principles and the spirit guides the application.

As we move forward, dramas like Case No. 9 and the real-world reforms it echoes (from banning degrading tests to acknowledging forensic proof) are all signs of a society rediscovering the true spirit of its faith and humanity. The 7th century needed four eyewitnesses to declare the truth; the 21st century can let DNA and digital data speak when humans fall silent. In both cases, the goal is that truth prevails and innocents are safeguarded. A line has often been repeated in Islamic legal maxim: “Let the hudud (punishments) fall by doubts” – meaning, if you have any doubt, do not punish. Today, we can also say: “Let new forms of knowledge dispel doubt” – meaning, use all available truthful evidence to clarify what really happened, so the guilty cannot hide behind lack of eyewitnesses or the veil of secrecy.

In conclusion, the Quranic teaching of four witnesses was a product of divine wisdom for its time – a necessity to uphold justice in a world without forensic science. Our task now is not to discard that wisdom, but to translate it. The translation for today is this: in any allegation of adultery, rape, or sexual wrongdoing, we require compelling proof – the kind of proof that convinces an impartial mind of the truth. Whether that proof comes from four righteous companions who saw it with their eyes, or from a meticulously collected set of DNA markers on a microscope slide, or from the testimony of a survivor corroborated by credible supporting evidence, the essence remains the same. We will neither punish the innocent nor let the guilty go free if it’s within our means to establish the truth.

The Quran, often misrepresented as rigid, actually embeds a timeless principle of justice that can flex with time: “And when you judge between people, judge with justice” (Quran 4:58). Justice is the eternal value; four witnesses were one historic vehicle to get there. Now we have new vehicles. As Sehar’s fictional trial and countless real ones show, our journey toward justice continues – ever guided by the light of fairness that God’s guidance lit for us, and ever adapting our tools to keep that light shining bright.

In the story of Case No. 9, and in the reality of our legal evolution, we see a beautiful convergence: the courage to speak the truth, the knowledge to prove the truth, and the faith to uphold the truth. This convergence is what will ensure that the Quran’s values remain alive in the hearts and laws of people well into the 21st century and beyond. Just as Sehar’s stand inspires others to hope, understanding the real ethos behind Quranic laws can inspire us to create a more just society – one that honors both the letter and spirit of God’s guidance in our modern context. That is the ultimate epilogue: a community that learns from its past to improve its future, where divine principles and human progress walk hand in hand toward a horizon of greater justice and compassion.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment