Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

This report presents an exhaustive exegetical and jurisprudential analysis of the 60th chapter of the Quran, Surah Al-Mumtahanah (“She That is to be Examined”). Revealed in Medina during the critical interim between the Treaty of Hudaibiyah (6 AH) and the Conquest of Mecca (8 AH), this chapter serves as the primary constitutional text defining the sociopolitical and theological boundaries of the nascent Muslim community (Ummah). The report provides the complete English translation by M.A.S. Abdel Haleem, segmented into four thematic sections: verses 1-6, 7-9, 10-11, and 12-13.

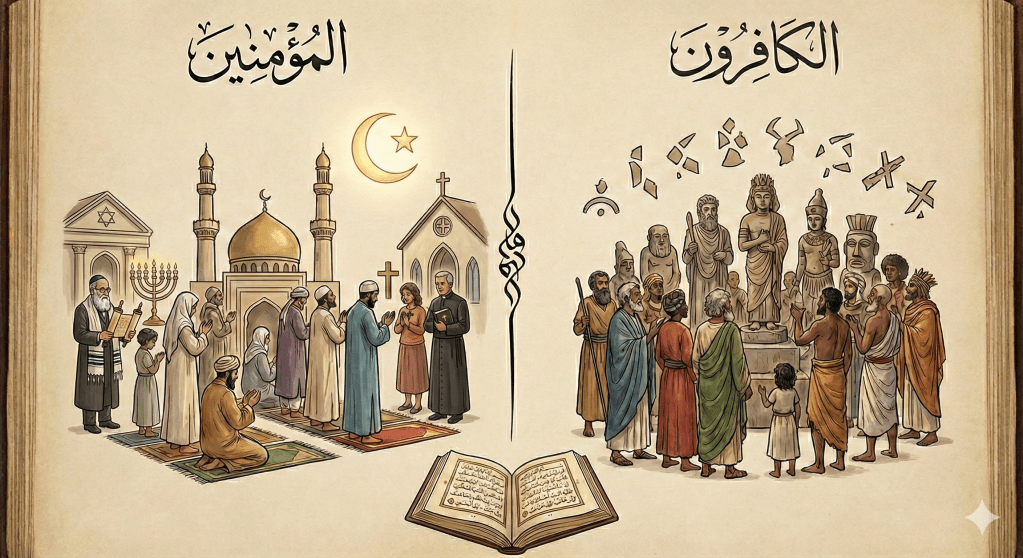

The core of this analysis interrogates the Quranic “separation of communities” established through marriage prohibitions. By synthesizing insights from Surah Al-Baqarah (2:221) and Surah Al-Mumtahanah (60:10), the report argues that the prohibition of intermarriage is a mechanism specifically designed to demarcate the monotheistic community from hostile polytheism (Shirk), rather than a blanket ban on all exogamy. This distinction is pivotal for understanding intra-Muslim sectarian relations; the report posits that the logic of separation cannot validly prohibit marriage between Muslim sects (e.g., Sunni and Shia) or, by extension of Surah Al-Ma’idah (5:5), interactions with the People of the Book. Furthermore, this study advances a rigorous, text-critical argument challenging the classical consensus on gender-based marriage restrictions. It suggests that the permission granted to Muslim men in Quran 5:5 to marry monotheists from the People of the Book logically extends to Muslim women, based on the Quranic rationale of “goodness” (tayyibat) and the absence of explicit gendered prohibition in that specific verse. The study concludes with a thematic epilogue synthesizing the Surah’s enduring framework for identity, loyalty, and gender agency.

I. Introduction: The Historical and Theological Context of Al-Mumtahanah

Surah Al-Mumtahanah occupies a unique space in the Quranic revelation, serving as both a spiritual guide and a document of international law. Its title, “She That is to be Examined” (Al-Mumtahanah), is derived from the instruction in verse 10 to test the faith of women emigrating from Mecca to Medina.1 This instruction was not merely procedural but represented a radical shift in the geopolitical norms of 7th-century Arabia, granting independent political asylum to women based on conscience rather than tribal affiliation.

The Surah was revealed against a backdrop of intense sociopolitical complexity. Following the Treaty of Hudaibiyah, the Muslim community in Medina had entered a tenuous truce with the Quraish of Mecca. This period was characterized by “mixed” families—believers in Medina with spouses, parents, and children still in Mecca—creating a crisis of loyalty. The revelation addresses the conflict between natural human affection (mawaddah) for kin and the supreme loyalty owed to the Divine (walayah), establishing the doctrine of al-wala’ wal-bara’ (loyalty and disavowal) while simultaneously tempering it with ethical nuances regarding non-hostile non-believers.

The Surah opens with a high-stakes incident of espionage involving a companion of the Prophet, Hatib ibn Abi Balta’ah, setting the stage for a discourse on the limits of diplomatic and personal intimacy with existential enemies. It then pivots to the treatment of refugees, the dissolution of marriages across religious lines, and the formal integration of women into the body politic through a specific pledge of allegiance. Throughout, the text balances the necessity of security with the imperatives of justice (qist) and benevolence (birr).

II. Section 1: Loyalty, Disavowal, and the Example of Abraham (Verses 1-6)

This opening section establishes the primary theme of the Surah: the prohibition of taking the active, hostile enemies of God as intimate allies. It addresses the internal psychological conflict faced by believers who had left relatives behind in enemy territory and sought to maintain diplomatic backchannels to protect them.

Translation (M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

60:1 You who believe, do not take My enemies and yours as your allies, showing them friendship when they have rejected the truth you have received, and have driven you and the Messenger out simply because you believe in God, your Lord—not if you truly emigrated in order to strive for My cause and seek My good pleasure. You secretly show them friendship—I know all you conceal and all you reveal—but any of you who do this are straying from the right path. 2

60:2 If they gain the upper hand over you, they will revert to being your enemies and stretch out their hands and tongues to harm you; it is their dearest wish that you may renounce your faith. 3

60:3 Neither your kinsfolk nor your children will be any use to you on the Day of Resurrection: He will separate you out. God sees everything you do. 4

60:4 You have a good example in Abraham and his companions, when they said to their people, ‘We disown you and what you worship besides God! We renounce you! Until you believe in God alone, the enmity and hatred that has arisen between us will endure!’—except when Abraham said to his father, ‘I will pray for forgiveness for you though I cannot protect you from God’—[they prayed]: ‘Lord, we have put our trust in You; we turn to You; You are our final destination. 5

60:5 Lord, do not expose us to mistreatment [at the hands of] the disbelievers. Forgive us, Lord, for You are the Almighty, the All Wise.’ 6

60:6 Truly, they are a good example for you [believers] to follow, a good example for those who fear God and the Last Day. If anyone turns away, [remember] God is self-sufficing and worthy of all praise. 7

Commentary

The Occasion of Revelation: The Case of Hatib ibn Abi Balta’ah

The exegetical tradition is unanimous that these verses were revealed concerning Hatib ibn Abi Balta’ah, a Companion who had migrated to Medina but remained vulnerable because he lacked tribal protection (jiwar) in Mecca, unlike the Quraishi emigrants.8 When the Prophet Muhammad secretly mobilized the army for the Conquest of Mecca (following the Quraish’s violation of the Treaty of Hudaibiyah), Hatib sent a secret letter to the Meccan leadership, warning them of the impending march. His motivation was not apostasy but a desperate attempt to curry favor with the Quraish to ensure the safety of his children and property left behind.9

Divine revelation informed the Prophet of this breach. He dispatched Ali ibn Abi Talib and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam to intercept the courier—a woman traveling to Mecca—at Rawdat Khakh. After initially denying she had the letter, she produced it from her hair braids under threat of search.9 When confronted, Hatib pleaded, “I did not do this out of disbelief… but I wanted to have a hand with the Quraish so they would protect my family.” While Omar ibn al-Khattab demanded his execution for treason, the Prophet accepted his excuse, citing his status as a veteran of Badr.9

Verse 1 serves as a divine critique of this incident. It reframes the political act of espionage as a theological error. The verse highlights the contradiction in Hatib’s logic: offering “friendship” (mawaddah) to those who “have rejected the truth… and driven you out.” It underscores that political allegiance cannot be severed from spiritual identity. The phrase “I know all you conceal and all you reveal” acts as a panopticon of divine surveillance, reminding the believer that secret diplomatic channels are fully transparent to God.2

The Anatomy of Enmity (Verse 2)

Verse 2 provides the sociological rationale for the prohibition of alliance. It argues that the enmity of the Meccan polytheists is structural, not merely situational. “If they gain the upper hand… they will stretch out their hands and tongues to harm you.” This vivid imagery describes total warfare: physical violence (“hands”) and propaganda/psychological warfare (“tongues”).3

Crucially, the verse identifies the ultimate goal of this enmity: “it is their dearest wish that you may renounce your faith” (waddū law takfurūn). This establishes that the conflict is not over resources or territory, but over the very soul of the community. This distinction is vital for jurisprudence; the “enemy” defined here is not the non-Muslim per se, but the belligerent force that actively seeks the annihilation of the Islamic faith. This justifies the “separation” of the communities—a theme that will recur in the marriage prohibitions.

The Deconstruction of Lineage (Verse 3)

In pre-Islamic Arabia, nasab (lineage) was the primary axis of social organization and survival. Verse 3 dismantles this idolization of kinship. “Neither your kinsfolk nor your children will be any use to you…” This is a radical reorientation of value. Hatib’s betrayal was motivated by love for his children, a natural instinct. The Quran acknowledges this instinct but subordinates it to the higher moral order of the Hereafter. The phrase “He will separate you out” (yafsilu baynakum) on the Day of Judgment implies that biological ties will be severed if they are not bonded by shared faith.4

The Paradigm of Abraham (Verses 4-6)

To replace the tribal model of loyalty, the Quran introduces the “Millat Ibrahim” (Creed of Abraham). Verses 4-6 present Abraham as the Uswa Hasana (Excellent Example) of total disavowal (Bara’).

The declaration in Verse 4 is the manifesto of religious separation: “We disown you and what you worship besides God! We renounce you!” This separation is comprehensive, rejecting both the people (for their hostility) and their theology (idolatry). The verse establishes that “enmity and hatred” will endure “until you believe in God alone.”

However, the text includes a profound nuance: “except when Abraham said to his father, ‘I will pray for forgiveness for you…’” This exception highlights the tension between public disavowal and private hope. Abraham disassociated from his community’s actions but retained a desire for his father’s salvation until it became clear he was a definitive enemy of God.10 This signals to the companions of Muhammad that while they must politically disengage from the Meccans, they may still harbor hope for their guidance—a hope that Verse 7 explicitly validates.

The prayer in Verse 5, “do not expose us to mistreatment” (literally: “do not make us a fitna [trial] for those who disbelieve”), is a strategic supplication. If the believers were to be defeated or crushed by the polytheists, it would serve as a “trial” for the disbelievers, confirming them in their arrogance that their idolatry was superior to monotheism. Thus, the political success of the community is tied to the theological validation of their message.6

III. Section 2: The Nuance of Benevolence and Justice (Verses 7-9)

Having established the severity of disavowal from hostile forces, the Surah immediately pivots to qualify the nature of relationships with non-believers, preventing the community from descending into indiscriminate xenophobia or perpetual war. This section is the cornerstone of Islamic international relations and inter-community ethics.

Translation (M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

60:7 ˹In time,˺ Allah may bring about goodwill between you and those of them you ˹now˺ hold as enemies. For Allah is Most Capable. And Allah is All-Forgiving, Most Merciful. 11

60:8 Allah does not forbid you from dealing kindly and fairly with those who have neither fought nor driven you out of your homes. Surely Allah loves those who are fair. 11

60:9 Allah only forbids you from befriending those who have fought you for ˹your˺ faith, driven you out of your homes, or supported ˹others˺ in doing so. And whoever takes them as friends, then it is they who are the ˹true˺ wrongdoers. 11

Commentary

The Prophecy of Reconciliation (Verse 7)

Verse 7 acts as a psychological intervention. The intense commands of disavowal in the previous section could easily harden the hearts of the believers into permanent hatred. God intervenes with a promise: “Allah may bring about goodwill (mawaddah) between you and those of them you now hold as enemies.”

This prophecy was fulfilled dramatically with the Conquest of Mecca. The very leaders of the Quraish who had persecuted the Muslims—such as Abu Sufyan and Safwan ibn Umayyah—eventually embraced Islam, transforming from “enemies” into “brothers” within a span of years. This verse teaches that enmity in Islam is transient and conditional; it is not an immutable state. The believer must always leave the door open for transformation, as God is “Most Capable” (Qadir) to turn hearts.12

The Constitutional Distinction (Verses 8-9)

Verses 8 and 9 provide the legal framework for relations with non-Muslims, creating a binary classification based on conduct rather than belief.

1. The Peaceful Non-Combatants (Verse 8):

For those who “neither fought nor driven you out,” the Quran prescribes two specific ethical duties:

- Tabarruhum (Benevolence/Kindness): Derived from Birr, the same root used for Birr al-Walidayn (piety toward parents). This denotes a high degree of warmth, generosity, and active care, not merely “tolerance” or “non-aggression”.13

- Tuqsitū (Justice/Fairness): Derived from Qist, meaning equity. This requires Muslims to uphold the rights of non-Muslims scrupulously in all dealings.

This verse was revealed, according to some traditions, regarding Qutaylah bint Abd al-Uzza, a polytheist woman who visited her Muslim daughter, Asma bint Abi Bakr, in Medina bearing gifts. Asma, unsure if she could interact with her polytheist mother, refused her entry until she consulted the Prophet. The Prophet confirmed, based on this verse, that she must honor her mother and accept her gifts, despite the difference in faith.14 This establishes that family ties and social courtesy transcend religious boundaries when no hostility exists.

2. The Hostile Belligerents (Verse 9):

The prohibition of Tawalli (alliance/protection/intimacy) is restricted exclusively to those who:

- Fought against the Muslims for their faith.

- Expelled them from their homes.

- Aided others in this expulsion (e.g., allies of the Quraish).

This precise demarcation refutes extremist interpretations that posit a state of perpetual warfare against all Kuffar (disbelievers). The text explicitly states “Allah does not forbid you” regarding the peaceful, validating the permissibility of social integration, economic trade, and neighborly relations with non-hostile non-Muslim communities.15

| Category of Non-Believer | Defining Action | Quranic Command | Legal Status |

| Al-Musalim (Peaceful) | Did not fight; did not expel. | Birr (Kindness) & Qist (Justice) | Permissible ally/friend. |

| Al-Muharib (Belligerent) | Fought; expelled; aided expulsion. | Nahy (Prohibition of Alliance) | Enemy; Wala is forbidden. |

IV. Section 3: The Examination of Women and the Boundaries of Marriage (Verses 10-11)

This section contains the legal crux of the Surah and the focal point of our analysis regarding inter-community boundaries. It modifies the Treaty of Hudaibiyah and establishes the regulations for dissolving marriages between communities at war.

Translation (M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

60:10 O believers! When the believing women come to you as emigrants, test their intentions—their faith is best known to Allah—and if you find them to be believers, then do not send them back to the disbelievers. These ˹women˺ are not lawful ˹wives˺ for the disbelievers, nor are the disbelievers lawful ˹husbands˺ for them. ˹But˺ repay the disbelievers whatever ˹dowries˺ they had paid. And there is no blame on you if you marry these ˹women˺ as long as you pay them their dowries. And do not hold on to marriage with polytheistic women. ˹But˺ demand ˹repayment of˺ whatever ˹dowries˺ you had paid, and let the disbelievers do the same. That is the judgment of Allah—He judges between you. And Allah is All-Knowing, All-Wise. 16

60:11 If any of you have wives who leave you for the disbelievers, and if your community subsequently acquires [gains] from them, then pay those whose wives have deserted them the equivalent of whatever bride-gift they paid. Be mindful of God, in whom you believe. 17

Commentary and Extended Analysis: The Demarcation of Communities through Marriage

The “Test” and the Treaty Exception

The Treaty of Hudaibiyah included a clause stating that any male Quraishi who fled to Medina without his guardian’s permission must be returned to Mecca. However, the treaty used the term Rajul (man), leaving the status of women ambiguous. When women like Umm Kulthum bint Uqbah (daughter of a prominent Meccan leader) fled to Medina, her brothers arrived to demand her return under the treaty. In response, Verse 10 was revealed, prohibiting the return of believing women to the Kuffar.18

The “Test” (Famtahinūhunna) was mandated to verify that their migration was motivated by Iman (faith) and love for God, rather than worldly motives such as fleeing a bad marriage or seeking a new husband. Once their sincerity was established, they were granted political asylum and their marital bonds to unbelievers were dissolved.8

The Separation of Communities via Marriage Prohibition

The verse issues a definitive legal ruling: “These women are not lawful for the disbelievers, nor are the disbelievers lawful for them.” Simultaneously, it commands Muslim men: “And do not hold on to marriage with polytheistic women” (lā tumsikū bi-ʿiṣam al-kawāfir).

This establishes the Quranic mechanism of community separation through marriage. In the tribal structure of Arabia, marriage was a treaty of alliance. Allowing a Muslim woman to remain married to a hostile polytheist (who actively fought Islam) was tantamount to handing over a citizen of the Muslim state to the enemy. Similarly, a Muslim man keeping a polytheist wife in Mecca would have divided loyalties. The prohibition was a necessary measure to consolidate the Ummah as a distinct political and spiritual entity, separated from the Mushrikīn (polytheists) who threatened its existence.

Embellishment: Insights from Quran 2:221

To understand the theological depth of this prohibition, one must look to Quran 2:221, which provides the foundational rationale:

“Do not marry polytheistic women until they believe; for a believing slave-woman is better than a free polytheist, even though she may look pleasant to you. And do not marry your women to polytheistic men until they believe, for a believing slave-man is better than a free polytheist, even though he may look pleasant to you. They invite ˹you˺ to the Fire while Allah invites ˹you˺ to Paradise…” (Quran 2:221, Abdel Haleem Translation).19

The rationale provided is stark: “They invite to the Fire.” This “invitation” is not merely metaphysical; in the context of the revelation, the polytheists were actively coercing believers to renounce monotheism (as noted in 60:2). The prohibition creates a firewall against this spiritual danger.

Crucial Distinction: The Case of “People of the Book” and Muslim Sects

It is paramount to emphasize that the “separation” logic of 2:221 and 60:10 applies specifically to Polytheists (Mushrikīn). This logic cannot be legally or theologically applied to prohibit marriage between Muslim sects or, arguably, with the People of the Book, because the Quran explicitly distinguishes these groups.

1. The Validity of Intra-Muslim Marriages (Sects):

The Quranic prohibition is predicated on Shirk (associating partners with God) and Kufr (rejection of Truth). Divergences between Muslim sects—such as Sunni, Shia, or Ibadhi—do not constitute the Shirk described in 2:221. All these groups adhere to the fundamental Shahada (Testimony of Faith). Therefore, the “separation of communities” argument cannot be weaponized to invalidate marriages between Sunnis and Shias. Both are part of the single Ummah of “Believers” (Mu’minūn). Any attempt to apply 2:221 to Muslim sects is a misapplication of the text, equating fellow monotheists with the idolaters of Mecca.20

2. The Exemption of the People of the Book (Quran 5:5):

The Quran explicitly removes Jews and Christians from the blanket prohibition of 2:221. This is codified in Quran 5:5:

“Today all good things have been made lawful for you. The food of the People of the Book is lawful for you as your food is lawful for them. So are chaste, believing, women as well as chaste women of the people who were given the Scripture before you, as long as you have given them their bride-gifts and married them, not taking them as lovers or secret mistresses…” (Quran 5:5, Abdel Haleem Translation).22

This verse, revealed towards the end of the Prophet’s life (in Surah Al-Ma’idah), clarifies that the People of the Book are not the “Polytheists” referred to in 2:221. The permission to marry them signals that despite theological differences, they share a monotheistic foundation that does not inherently “invite to the Fire” in the same existential way as paganism. The Quran allows for social integration (food and marriage) with them, distinguishing them from the hostile “Other” of 60:10.23

Theological Argument: Does the Permission Apply to Muslim Women?

Traditional Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh) has universally interpreted 5:5 as an asymmetric permission: Muslim men may marry women of the Book, but Muslim women may not marry men of the Book. However, a text-critical reading, supported by some modern scholars, suggests a different possibility when the verses are viewed in totality.

The Argument for Symmetry:

- The Criterion of “Goodness” (Tayyibat): Quran 5:5 begins with the declaration: “Today all good things (Al-Tayyibat) have been made lawful for you.” It then lists chaste women of the Book as one of these “good things.” If a marriage to a monotheist is considered “good” and “lawful” for a man, the Quranic principle of spiritual equality suggests it possesses the same “goodness” for a woman, unless explicitly restricted.

- Absence of Explicit Prohibition: There is no verse in the Quran that explicitly says, “Muslim women cannot marry People of the Book.” The prohibition in 2:221 is against Mushrikīn (polytheists). Since 5:5 essentially removes the People of the Book from the category of prohibited Mushrikīn for men, the silence regarding women is significant.

- Contextualizing 60:10: The prohibition in 60:10 (“They are not lawful for them”) was revealed regarding the Kuffar of Mecca—hostile polytheists at war with Islam. Applying this verse to forbid a Muslim woman from marrying a peaceful Christian or Jew in a modern context conflates two distinct theological categories: the hostile Mushrik and the scriptural Kitabi.25

- Sociological vs. Theological Barriers: Reformist scholars like Khaled Abou El Fadl and Asma Lamrabet argue that the traditional restriction was based on the sociological reality of 7th-century patriarchy, where a woman entered the tribe and religion of her husband. In such a context, a Muslim woman marrying a non-Muslim would be lost to the community (violating the separation logic). However, in modern legal systems where women retain their independent legal and religious identity, the “existential threat” to her faith is removed. Therefore, if the Illah (legal cause) of the prohibition was the loss of faith/identity, and that cause is absent, the ruling may be re-evaluated.27

Conclusion on Marriage: The Quran separates the Muslim community from Polytheists to preserve its spiritual core. It connects the Muslim community to People of the Book (via 5:5) to acknowledge shared Abrahamic roots. The suggestion that this connection could validly extend to Muslim women—provided their faith is secure—is a plausible extension of the Quran’s logic of “goodness” and the specific removal of the “Fire” warning associated with polytheists.

V. Section 4: The Covenant of Women (Verses 12-13)

The final section details the formal integration of women into the political and spiritual community through a specific pledge (Bai’ah). This section is revolutionary in its recognition of women as independent legal agents capable of contracting a covenant with the Prophet directly.

Translation (M.A.S. Abdel Haleem)

60:12 O Prophet, when the believing women come to you pledging to you that they will not associate anything with Allah, nor will they steal, nor will they commit unlawful sexual intercourse, nor will they kill their children, nor will they bring forth a slander they have invented between their arms and legs, nor will they disobey you in what is right—then accept their pledge and ask forgiveness for them of Allah. Indeed, Allah is Forgiving and Merciful. 29

60:13 You who believe, do not take as allies those with whom God is angry: they despair of the life to come as the disbelievers despair of those buried in their graves. 30

Commentary

The Women’s Pledge (Bai’ah al-Nisa’)

Verse 12 outlines the terms of the oath administered to women converts. This was not merely a spiritual ritual but a political act of allegiance to the new order. The conditions listed—avoiding shirk, theft, adultery, infanticide, and slander—target the specific social ills prevalent in pre-Islamic Arabia.

The mention of infanticide (“kill their children”) directly addresses the pre-Islamic practice of burying infant daughters alive, marking Islam’s intervention in defense of the rights of the girl-child. The phrase “slander they have invented between their arms and legs” is interpreted by exegetes to refer to attributing an illegitimate child to a husband, a critical protection of lineage.31

The Condition of Ma’ruf (Righteousness)

A profound constitutional principle is embedded in the phrase: “nor will they disobey you in what is right (ma’ruf).” Even obedience to the Prophet—the divinely appointed leader—is textually qualified by the condition that the command must be ma’ruf (good/recognized as right). This implies that in Islam, there is no absolute, blind obedience to any human being if they command what is contrary to God’s law. This clause establishes the supremacy of principle over person, even regarding the Messenger himself in his administrative capacity.31

The Agency of Hind bint Utbah

The historical application of this verse is best illustrated by Hind bint Utbah, the wife of Abu Sufyan. Once the arch-enemy of Islam who mutilated the body of Hamza (the Prophet’s uncle), she came to take this pledge after the Conquest of Mecca. When the Prophet recited the condition “nor will they steal,” Hind famously interrupted, asking, “O Messenger of Allah, Abu Sufyan is a stingy man. Is there any sin on me if I take from his wealth to feed our children?” The Prophet replied, “Take what is sufficient for you and your children with kindness.”

This interaction highlights two key insights:

- Interactive Agency: The pledge was a dialogue, not a silent submission. Hind felt empowered to negotiate the terms based on her domestic reality.

- Reconciliation: The fact that Hind—a woman with “blood on her hands”—was accepted into the covenant underscores the Surah’s theme of forgiveness. Her past enmity was erased by her present pledge, fulfilling the prophecy of Verse 7.8

Final Warning (Verse 13)

The Surah closes by circling back to the theme of Wala’. It warns against allying with “those with whom God is angry.” While some exegetes link this to specific Jewish tribes in Medina who violated treaties, the description fits any group that actively opposes the Divine truth with hostility. The description of their despair “as the disbelievers despair of those buried in their graves” paints a picture of a worldview trapped in materialism, devoid of hope in the Hereafter. This contrasts the believer, whose alliances are dictated by eternal hope, with the disbeliever, whose alliances are driven by temporary, worldly fears.30

VI. Thematic Epilogue: The Examined Life and the Boundaries of Community

Surah Al-Mumtahanah serves as a divine constitution for a community in transition. It navigates the delicate balance between ideological purity and social pragmatism, erecting walls to protect the community from existential threats while simultaneously building bridges of mercy.

The “Examination” (Mumtahanah) is not merely a historical vetting of female refugees; it is a metaphor for the perpetual testing of the believer’s loyalties. The Surah acknowledges the complexity of human emotion—the love for family, the pull of ancestry, the fear of loss—but subordinates these to the supreme value of Tawhid (Monotheism).

Crucially, the juxtaposition of the prohibitions in 2:221/60:10 and the permissions in 5:5 reveals a Quranic intent to separate the Muslim community specifically from Idolatry (Shirk), not from the broader monotheistic family. By framing marriage prohibitions through the lens of spiritual safety (“They invite to the Fire”) rather than tribal exclusion, the Quran opens pathways for coexistence with the People of the Book. The reformist insight—that the “lawful” nature of People of the Book in 5:5 could theoretically encompass both genders—challenges rigid patriarchal readings. It suggests that the ultimate criterion for a valid union is a shared foundation in God-consciousness and chastity, rather than a mere identity label.

In an era of global sectarianism, the Surah’s implicit validation of all believers—regardless of sect—as a single brotherhood, and its nuanced approach to interfaith relations, offers a timeless framework. It defines identity not by who we hate, but by the principles we uphold, warning us that while we must disavow hostility, we must never disavow justice. The “examined woman” of the 7th century thus prefigures the “examined conscience” of the modern believer, constantly weighing the demands of faith against the complexities of a pluralistic world.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment