Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

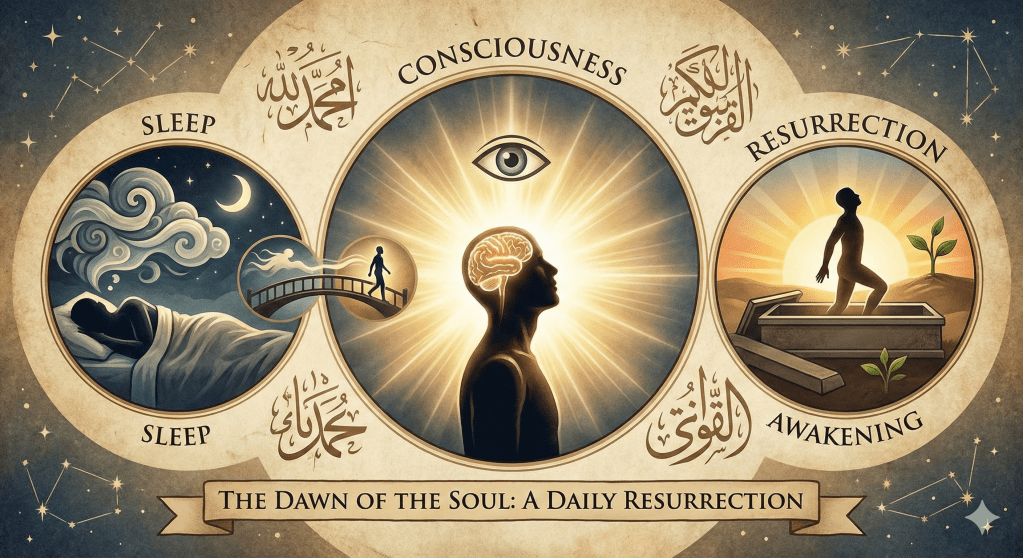

Sleep, in the Islamic scripture, is far more than a biological necessity – it is presented as a divine sign and a daily reminder of death and resurrection. Qur’an 39:42 and 25:47 explicitly draw an analogy between sleeping and dying on the one hand, and awakening and resurrection on the other. Every night, God “takes your souls” during sleep as if in a minor death, and each morning “the day [is made] a resurrection” (Qur’an 25:47) – framing each new dawn as a kind of rebirth. This commentary explores these verses through theological, scientific, and philosophical lenses. Classical Islamic scholars viewed sleep as al-mawt as-sughra (the “minor death”), emphasizing God’s power to restore life daily as a sign of the ultimate Resurrection. Modern neuroscience, while describing sleep in terms of brain activity and consciousness, intriguingly affirms that human consciousness can switch “off” and “on” again, hinting at the plausibility of revival by a higher power. Philosophers ancient and modern have long asked: where does the self go during sleep? By examining Qur’anic exegesis, sleep science, and reflections on the soul, we find a rich harmony: the daily cycle of sleep and awakening emerges as both a practical mercy and a profound metaphor for life, death, and beyond. In conclusion, cultivating a morning meditation on these truths can inspire greater God-consciousness, moral accountability, and hope in the promised Resurrection.

Quranic Insights: Sleep as “Minor Death” and Awakening as Resurrection

Qur’an 39:42 provides a cornerstone for understanding the sleep-death analogy. It proclaims: “Allah takes the souls at the time of their death, and those that do not die [He takes] during their sleep. Then He keeps those for which He has decreed death and releases the others for an appointed term. Indeed in that are signs for people who reflect.”. In this verse, the same term tawaffā (“to take in full”) is used for both taking a soul at death and taking it during sleep, suggesting that sleep is a partial withdrawal of the soul while death is a complete one. Each night, God “calls back” our souls; if our lifespan (ajal) is not yet complete, He mercifully releases the soul back to awaken us for another day. If one’s appointed end has come, the soul is kept and does not return – the sleeper dies in his sleep. As the verse emphasizes, “in that are signs for those who reflect”, meaning that anyone pondering this daily phenomenon can intuit God’s power over life and death.

Classical Islamic scholars have commented extensively on this verse. The early exegete Ibn ʿAbbās reportedly explained that during sleep “their souls are taken… such that the souls of the living meet the souls of those who have passed away”, conversing until the living are returned to their bodies upon waking. Whether understood literally or metaphorically, this idea illustrates that the soul has a life beyond the body’s consciousness. Many scholars described sleep as “al-mawt as-sughra” (minor death) and death as a longer sleep; in both cases the body lies inert, “devoid of consciousness – partially and temporarily in [sleep], completely and permanently in [death]”. No soul returns from death until the Resurrection, but souls do return from sleep by God’s command every morning, underscoring His ongoing agency in our lives. The Qur’an itself makes this parallel explicit in another verse: “He is the One who takes your souls by night…and He raises you up again [each day] until an appointed term is fulfilled” (Qur’an 6:60) – just as an alarm clock can wake a sleeper but cannot wake a corpse.

Qur’an 25:47 highlights the flip side of the analogy by focusing on awakening. It says: “And it is He who has made the night a covering for you, and sleep a means for rest, and has made the day a resurrection (nushūr).”. Here nushūr literally means “raising to life” or “spreading forth”, implying that each awakening is akin to being raised from the dead. After the lifeless stillness of sleep, the burst of energy and activity each morning is like a mini-revival. Classical commentators note that this verse “subtly teaches the reality of the Resurrection through the daily experience of rising from sleep”. Just as God restores our consciousness after a night’s slumber, He will just as assuredly restore life to the dead on the Last Day. The verse begins by describing night as a covering or garment – a time when worldly activity is folded away – and sleep as repose for the body and mind. Then by calling the day a “resurrection,” the Qur’an invites us to see every single day as a sign of the coming Day when all lives will be renewed. It is an invitation to reflect (tafakkur) on the cycle of life built into our very routine: “Surely there are signs in this for people who reflect.”.

Both verses (39:42 and 25:47) convey a clear theological message: our daily sleep-wake cycle is a deliberate sign from God, meant to remind us of His power to give life, cause death, and resurrect. The Qur’an pairs sleep and wakefulness as one of the āyāt (signs) of divine wisdom: “And of His signs is your sleep by night and day and your seeking of His bounty [by day]…” (30:23). We spend roughly one-third of our lives in the powerless state of sleep, and this rhythm is not accidental but compassionate – a built-in rest for our bodies and a daily pause for our souls. As scholar Abu Ala Maududi observes, even the strongest human is forced to surrender to sleep, and “no matter how powerful a person may be, he has no guarantee that he will certainly get up alive in the morning”. Each night’s vulnerability and each morning’s return to life are thus humbling signs of our dependence on God. The Qur’an’s message is that these signs should not be lost on us: our creator and sustainer who designed this cycle can just as easily gather our souls at death and revive us in a new life. Or as one Muslim scholar succinctly put it: “Sleep is a minor death and death a major sleep, all under God’s control.”

Scientific Perspectives: Consciousness “On Pause” – Parallels in Sleep and Death

Modern science approaches sleep as a physiological phenomenon, but its findings unwittingly echo the Qur’anic metaphors. Neuroscience shows that during deep sleep, our conscious awareness is largely “switched off,” and yet, in most cases, it switches on again with awakening. In fact, the daily cycle of consciousness ceasing and reemerging can be seen as a natural prototype of losing and regaining life. As one research-oriented commentary notes, the very fact that our bodies and minds can “power down” for hours and then reboot intact is a “gentle intimation that the One who designed our bodies to ‘switch off’ and ‘on’ can surely raise the dead.”. From a scientific standpoint, sleep involves extremely complex brain regulation. The brain’s reticular activating system keeps us awake, while sleep-promoting centers in the hypothalamus shut down our awareness at the appropriate time. Brain waves in deep sleep (slow-wave sleep) show greatly reduced and synchronized cortical activity, resembling a state of diminished consciousness. Yet this state remains reversible – after some hours, brain activity ramps up again (during REM sleep and then full wakefulness) and consciousness returns.

Fascinatingly, advances in medicine have created states analogous to sleep where consciousness is suspended. General anesthesia, for example, can induce a coma-like oblivion from which a patient may awake hours or even days later with no memory – essentially a controlled “death-like” state. Patients “die” to consciousness under anesthesia and are then revived by withdrawing the anesthetic, paralleling the Quranic idea of God sending the soul back until its appointed time. Even more striking, doctors have developed techniques of inducing hypothermic suspended animation, drastically slowing metabolism to near standstill in emergency trauma care, then rewarming the body to “reanimate” the patient. Nature too provides analogies: certain animals hibernate, entering a prolonged sleep where heartbeat and breathing almost stop, yet they awaken months later. These examples show that the boundary between life and lifelessness is more porous than we might assume. As Zia H. Shah observes, scientific explorations of sleep and its cousins (anesthesia, hibernation, coma) reveal phenomena that “make the age-old scriptural metaphors look less like mere metaphor and more like actual facets of reality waiting to be understood.”. In other words, while science does not pronounce on the supernatural, its discoveries about consciousness and the brain reinforce – rather than undermine – the plausibility of resurrection, by showing that life can be suspended and restarted in unexpected ways.

Neuroscience also highlights how protected our sleep is. Unlike death, sleep is kept within safe biological limits by multiple regulatory mechanisms. The brain’s chemistry ensures we do not slip irreversibly into a coma each night. Neurotransmitters like norepinephrine, serotonin, and orexin act as safeguards, preventing the brain from descending into dangerously deep unconsciousness except when intended. This scientific insight resonates with the Quranic notion that sleep and waking are actively managed by God. It is as if Providence installed fail-safes so that each night’s “little death” reliably returns to life by morning. Our very physiology, then, is a testament to the intentional design behind the sleep-wake cycle, aligning with the Qur’an’s portrayal of God’s mercy in giving us sleep for rest, and His power in bringing us back to life each day.

Moreover, research into near-death experiences (NDEs) has provided intriguing data about consciousness at the edge of death. People revived from clinical death (their heart stopped, brain activity flatlined) sometimes report lucid experiences—suggesting that consciousness might continue or resume even when the body is essentially dead. Often, survivors describe the moment of resuscitation as feeling like “waking up” from a far-away place. Such reports uncannily mirror the Quranic description of God taking souls and then returning them for an appointed term. While not definitive proof of an afterlife, these phenomena hint that the “off switch” of death may not be permanent and that human selfhood might transcend the body’s shutdown. In sum, modern science, from chronobiology to critical care medicine, reveals patterns of reversible unconsciousness and revival that beautifully parallel the Quranic metaphor of sleep and awakening as signs of death and resurrection. The more we learn about life’s resilience, the more credible the promise “He will give them life after death” becomes – at least to those who, as the Qur’an says, are willing to reflect.

Philosophical Reflections: Mind, Soul, and the Continuity of Consciousness

Sleep has long fascinated philosophers and theologians because it raises fundamental questions about consciousness and identity. In the materialist view, consciousness is tied to brain activity – and in deep sleep, that activity fades. Yet from the first-person perspective, one perceives going to sleep as an almost immediate “jump” to waking hours later, with time unaccounted for. As one scholar muses, sleep presents the ‘Hard Problem of Consciousness’ in its most acute daily form: Where does the “Self” go when the body lies inert?. The Islamic conception answers that the rūḥ or nafs (soul-self) is entrusted to God during sleep, even as the body lives on in a vegetative state. This view, shared by many religious and dualist philosophers, posits that our identity is not erased in sleep; rather, the soul remains intact and resumes full connection with the body upon waking. The mind-body dualism implicit here has been explored by thinkers like Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) and al-Ghazālī. Avicenna, for instance, argued for the soul’s independent existence through his famous “floating man” thought experiment, suggesting that even without sensory input (as in sleep or sensory deprivation) the self is aware of its own existence. Al-Ghazālī, on the other hand, used the analogy of dreams to explain prophecy and the afterlife – noting that in dreams one experiences realities that feel true, hinting that life itself may be a longer dream from which we will eventually awaken in the Hereafter.

The Qur’anic sleep/death analogy gave philosophers a rich metaphor for the human condition. Our life in this world, by comparison to the afterlife, is like a sleep compared to wakefulness. Abu Ḥamid al-Ghazālī beautifully stated that “this world is to the next as sleep is to wakefulness” – what we perceive now is fleeting and dreamlike, and only after we die do we truly awaken to an enduring reality. Mawlānā Rumi, inspired by such Quranic and philosophical insights, likewise taught: “This world is like sleep – our deeds are like dreams. But when we die, that is when we truly wake up.”. Such reflections encourage a view that our everyday consciousness is limited and veiled, much like a dream state, whereas the soul’s full reality will manifest after physical death. The temporary suspension of consciousness in sleep thereby becomes a window into metaphysics: it suggests that our essence can exist without active brain awareness (as it does each night), supporting the idea that the soul can survive the body’s total shutdown at death. Indeed, the continuity of personal identity despite nightly episodes of oblivion hints, as Shah observes, at “an enduring substratum, call it soul or continuity of consciousness, that persists” beyond the body.

From a moral-philosophical angle, recognizing each new day as a “minor resurrection” carries an implicit call to ethical living. If every morning is a miniature Judgment Day, as some sages have said, then one should awaken with gratitude and resolve – grateful for life returned, and resolved to use this renewed chance wisely. The person who awakens from sleep has, in essence, received life back as a gift; this invites reflection on whether we are living in accordance with our higher purpose. Philosophers of ethics in the Islamic tradition (and beyond) have drawn on this idea to advocate muhāsabah, regular self-accounting. For example, ʿUmar bin al-Khaṭṭāb is famously quoted as saying, “Take account of yourselves before you are taken to account [on Judgment Day].” The quiet time of early morning, right after the “resurrection” from sleep, is seen as an ideal moment for such introspection. It is a time when human heedlessness (ghaflah) is at its lowest – one has just been reminded of one’s mortality in the form of sleep. Thus, philosophical and spiritual traditions converge on the notion that mindful awareness of the sleep-death analogy can profoundly shape one’s consciousness, promoting an awakened life of purpose rather than a heedless life of denial.

Spiritual Implications: A Daily Wake-Up Call for Accountability and Faith

Contemplating Qur’an 39:42 and 25:47 every morning can transform a routine act – waking up – into a moment of spiritual awakening. These verses invite believers to see God’s hand in their very rise from bed each day. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ taught a short prayer to say upon waking: “Praise be to God who gave us life after He caused us to die, and unto Him is the resurrection.” This supplication, mirroring Qur’an 25:47’s message, encapsulates the mindset of a believer who views sleep as a form of death and the new day as a return to life by God’s grace. By starting the day with such a remembrance, one reinforces the belief that “unto Him is the Resurrection” – that ultimately we will return to God for final judgment. It is a potent cure for the modern malaise of materialism and denial of the Hereafter. Instead of shrugging off sleep as just a biological reset, a faithful person is reminded at dawn of the true Reset to come: al-Qiyāmah, the Day of Resurrection.

This daily meditation on resurrection nurtures God-consciousness (taqwā). One who reflects “I have been returned to life for a purpose” will be less likely to squander the gift of time. Each morning becomes an exercise in gratitude and responsibility. Gratitude, because you recognize life as a gift renewed – not an automatic right – and responsibility, because you recall that one day the morning will come when your soul is not returned, and you will face the consequences of your deeds. In the Qur’an’s words, “Each new dawn’s awakening is a quiet resurrection, a daily mercy that reflects the ultimate Resurrection to come.” Realizing this, a believer is moved to live righteously in the “day” of this life before the unending “Day” of eternity arrives. As the Qur’an often says, “Verily in this are signs for those who reflect.” Such reflection turns belief in the Resurrection from an abstract doctrine into a living, personal experience every single day.

Furthermore, seeing sleep and waking in this spiritual light combats the attitude of heedlessness (ghaflah) that the Qur’an warns against. Those who deny spiritual realities often do so because life lulls them into a sense of permanence; they “sleepwalk” through life, forgetting their divine origin and destiny. The Quranic metaphor shocks us out of this slumber. It tells us that every sleeper will one day not awake – meaning our life’s appointed term will end – and just as surely, God can resurrect all the sleepers from their graves as easily as He wakes us from bed. Pondering this, one cannot help but become more vigilant about one’s actions and choices. It engenders a healthy sense of accountability: just as we feel accountable for how we use each day after waking, knowing it is granted by God, we feel accountable for our entire lifespan, knowing a Day of Reckoning follows our death. In this way, daily wakefulness becomes a rehearsal for the Resurrection and the judgment to follow.

Crucially, the sleep-resurrection analogy also provides hope and consolation. Each new morning reminds us that God’s mercy hasn’t forsaken us. If you failed or sinned yesterday, today is a new chance – almost a new life in miniature – to repent and improve. This is why some spiritual teachers speak of “the ethic of wakefulness”: living each day as if it were a new life granted to prepare for the next. It’s notable that all Abrahamic faiths find hope in this metaphor. The Bible refers to death as “sleep” and describes the righteous dead as merely sleeping until God awakens them (e.g. John 11:11, 1 Thessalonians 4:14). Early Christians even called their graveyards “cemeteries,” literally meaning “sleeping places,” in firm hope of the coming resurrection. In Jewish thought, the Talmud states that “sleep is one-sixtieth of death,” and the morning prayer (Modeh Ani) thanks God for mercifully restoring one’s soul each day. All these traditions echo the Quran’s insight that daily rising is a signpost to the Resurrection. Thus, when a Muslim repeats each morning “Al-ḥamdu lillāh allathee aḥyānā ba‘da mā amātanā” (“Praise be to God who gave us life after having given us death”), they join a chorus of believers through time who found spiritual renewal in the dawn. Mindfully embracing this practice makes one’s faith in the Resurrection an ever-present reality, guiding one’s actions away from denial and toward remembrance.

Epilogue: Daily Awakening as a Sign of the Ultimate Resurrection

Every night, as we surrender to sleep, we enact a profound lesson. We relinquish our consciousness, trusting that it will be given back the next day – a trust we often take for granted, yet as the Qur’an reminds us, it is Allah who “returns” our souls in the morning. In the quiet vulnerability of sleep, kings and commoners alike lie helpless, kept alive only by the heartbeat and breath that God sustains. Then, each new dawn’s awakening is a quiet resurrection, a daily mercy that prefigures the ultimate Resurrection to come. As the 12th-century sage al-Ghazālī noted, “this world is to the next as sleep is to wakefulness” – what we experience now is fleeting and dreamlike, and only in the life hereafter will we awaken to true reality. Rumi, in poetic accord, said: “This world is like sleep – our deeds are like dreams. But when we die, that is when we truly wake up.”. Indeed, our nightly journey into oblivion and our reviving each morn are like a daily dress rehearsal for resurrection: “each day’s rising”, as one writer puts it, “is an opportunity to echo the ancient prayers: ‘Praise be to God who gave us life after death (sleep), and unto Him is the Resurrection.’”.

The convergence of these spiritual insights with modern knowledge inspires awe and hope. Our bodies’ cycles and nature’s seasons are woven with patterns of renewal: the seed that “dies” in the ground and sprouts anew, the trees that appear dead in winter and bloom in spring, the sleeper who vanishes into unconsciousness and reappears with the sunrise. The Qur’an draws attention to all of these as signs (āyāt). “He brings the dead earth to life – similarly you will be brought forth,” it says, linking natural revival to human resurrection. Just as rain revives the parched earth, the Trumpet of the Day of Judgment will revive souls from the dust. The daily rebirth of life each morning is a merciful sign that God does not leave us in eternal night. He is, as the Qur’an assures, “more anxious than you are” that we attain His forgiveness and grace. Recognizing this, we should not “sleepwalk” through our spiritual duties. Each day granted is a chance to seek our Creator’s pleasure and prepare for the Grand Morning when all sleepers finally awaken.

In the end, the Quranic metaphor of sleep and wakefulness teaches a unified lesson: the One who ordained our rest will surely ordain our resurrection. Our nightly oblivion and daily revival are not just mundane routines; they are profound parables about death and the Hereafter. For those with insight, every dawn whispers the promise that “He who never sleeps” is watching over creation and will one day call us forth to account. Let us then live with hearts awake. Each morning, as we open our eyes, we remember that one day we will open them to the Eternal Day – and thus we strive to live righteously in the time given. Praise be to God who gives us life after our little deaths, and to Him is the final Resurrection.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment