Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

Over the centuries, Islamic legal understanding has evolved in how it interprets the Quranic requirement of four witnesses for proving sexual misconduct, especially as science and forensic methods have advanced. Classical scholars viewed the “four-witness” rule in the 7th-century context as a nearly insurmountable evidentiary standard to protect individuals from slander and false accusations of adultery. In an era without forensic science, this high bar effectively deterred malicious claims and invasions of privacy, upholding personal honor. In modern times, however, scholars recognize that the same underlying principle of requiring clear proof can be met through forensic evidence – DNA, medical reports, CCTV, etc. – which can serve as “silent witnesses” with even greater certainty. This essay explores how the interpretation of the four-witness requirement has transitioned from a literal insistence on eyewitnesses to an emphasis on proof beyond reasonable doubt, integrating scientific evidence in line with Quranic intent. Furthermore, it discusses how similar context-driven principles should inform the application of Quranic hudud punishments – such as flogging for adultery or slander and amputation for theft – ensuring that the spirit of justice and mercy in Islamic law is upheld over a rigid literalism. By examining classical jurisprudence and contemporary perspectives, we find that fidelity to the spirit of the law sometimes necessitates adapting its letter. In doing so, the core objectives of the Sharia (justice, protection of society, and compassion) remain paramount, illustrating that evolving context can coexist with the eternal values of divine law.

Introduction

The Quran introduced legal mandates in the 7th century to cultivate a morally upright and just community. Surah An-Nur (Quran 24) famously lays out stringent conditions and penalties related to sexual ethics and personal honor. For example, it prescribes 100 lashes for proven adultery (zina) and 80 lashes for false accusations of unchastity (qadhf, slander) when the accuser cannot produce four witnesses. It even establishes a procedure (liʿān) for cases where a husband suspects his wife of adultery but lacks evidence, allowing each to swear oaths and invoke God’s curse if lying. At first glance, these punishments and evidentiary rules appear inflexible and harsh. However, both classical and modern Islamic scholars emphasize that such Quranic injunctions cannot be understood in isolation from their context and purpose. Surah An-Nur was revealed after the notorious incident of slander (al-Ifk) against ʿAisha, the Prophet’s wife, where false rumors of adultery spread in the community. In response, the Quran set an exacting standard of proof – four eyewitnesses – for sexual accusations, precisely to prevent baseless defamation from ruining innocent lives. Thus, the letter of the law (demanding four witnesses or else punishing the accuser) was aimed at upholding a higher spirit: protecting personal honor, promoting privacy, and deterring reckless allegations.

Crucially, the Quran’s punishments were paired with procedural safeguards that made their actual implementation exceedingly rare, reflecting a balance between moral strictness and mercy. Early Muslim jurists understood that the severity of a hudud penalty (like flogging or amputation) was counterbalanced by the stringency of evidence required to impose it. In other words, Islam set a lofty moral standard and a daunting evidentiary bar to match – ensuring that while serious crimes were formally condemned, in practice only the truly guilty (proven with certainty) would face such severe punishments. This interplay of high ideals and compassionate restraint is a key theme that has guided the interpretation and application of Islamic law through the ages.

As society has developed new tools of determining truth and alternative ways to maintain social order, Muslim thinkers have continually re-examined these Quranic laws. The advent of forensic science, modern state judicial systems, and evolving norms of justice raise the question: Should the Quran’s legal directives be applied exactly as in the 7th century, or should their application evolve with changing context? This essay delves into that question, focusing first on the “four witnesses” rule and then on the Quran’s prescribed punishments. By surveying classical exegesis and contemporary perspectives, we will see that Islamic jurisprudence has a rich tradition of adapting to serve justice – a tradition that today calls for aligning the letter of Quranic law with its ethical objectives in light of contemporary knowledge and circumstances.

The Four-Witness Rule: Classical Wisdom Behind a Strict Standard

In classical Islamic jurisprudence, the requirement of four eyewitnesses to prove adultery was never seen as a simple legal technicality – it was understood as a deliberate mechanism to uphold justice and social decorum. In the 7th-century Arabian context, forensic evidence did not exist and a person’s word or testimony was the primary means to establish facts. By insisting on not one or two, but four adult eyewitnesses to the act of illicit intercourse, the Quran effectively made it “nearly impossible” to legally prosecute someone for adultery in normal circumstances. Classical scholars recognized that this stringent requirement served multiple wise purposes:

- Protecting Honor and Privacy: The rule was revealed in the context of slander – specifically to halt the kind of false accusations that had targeted ʿAisha. As author Kaya Gravitter explains, the four-witness standard made accusations of adultery “nearly impossible without overwhelming proof, thereby shielding women’s honor from rumor, gossip, and sexual weaponization.” In a society where a woman’s reputation could be easily destroyed by a single accusation, this high bar was a merciful shield. It discouraged people from prying into others’ private lives and from turning personal grudges into public scandals.

- Deterring False Accusers: The flip side of requiring four witnesses was the Quran’s stern penalty for anyone who accused someone of sexual misconduct without meeting this criterion: such an accuser would themselves receive 80 lashes for slander (qadhf) and have their future testimony deemed untrustworthy. This rule virtually nullified “he-said, she-said” accusations. No matter how suspicious one might be, publicly accusing someone of adultery without hard proof would backfire on the accuser. Classical jurists saw in this a powerful deterrent against frivolous or malicious allegations. It protected the social fabric from descending into a culture of mistrust and public shaming.

- Emphasizing Moral Seriousness without Vigilantism: By setting an almost unreachable evidentiary standard, the Quran signaled that while adultery is a grave sin, prosecuting it was not encouraged except in undeniable cases. This prevented zealous individuals from turning into morality police. As the commentary on these verses notes, “Islam neither trivializes sexual sin nor permits witch-hunts under the guise of piety.” The community was taught to uphold chastity as an ideal, yet not to snoop or spy on others – a principle known in Islamic ethics as avoiding tajassus (intrusive surveillance). The law thus maintained public decency without fueling vigilantism, striking a balance between moral discipline and personal privacy.

It is important to clarify that the classical ulema (scholars) understood the four-witness rule to apply only to consensual zina (adultery/fornication) and not to rape. Rape (Arabic: ightiṣāb) was treated as a separate crime entirely, often falling under the category of violent aggression (hirabah, “banditry”) rather than zina. A woman alleging rape was not required to produce witnesses to avoid punishment – such a requirement would be absurd and cruel, effectively punishing the victim. In fact, classical jurists across all major schools exempted coerced women from any hudud punishment, recognizing them as victims. They debated what evidence sufficed to prove coercion: for instance, Maliki jurists were very forward-thinking, classifying rape as hirabah (a crime of violence against society) punishable even by death or crucifixion, and they accepted circumstantial evidence like a prompt pregnancy or distress calls as proof of rape. The Hanafi jurists were somewhat stricter, historically looking for signs of struggle or immediate outcry as evidence of non-consent. But importantly, no reputable classical authority ever said a rape victim must present four witnesses to avoid being charged with adultery – that conflation was a tragic misapplication by later literalist courts, not the intent of the Sharia. In summary, the classical Islamic legal system built a dual-layered approach: for the hadd (fixed Quranic) punishment of zina, the four-witness rule was absolute; but in the absence of such proof, judges could still impose tazir (discretionary punishments) based on lesser evidence to deal with wrongdoing without invoking the hadd. This meant a rapist or an adulterer might face a jail term, flogging, or other penalties on the basis of strong but less-than-four-witness evidence, ensuring that criminals did not walk free even when the strict hadd standard couldn’t be met. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and his successors also showed flexibility – for example, the second Caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab famously suspended the hand-cutting punishment for theft during a famine, understanding that context (widespread hunger) must temper enforcement of the law. All these classical precedents highlight that the letter of the law was never meant to override its spirit of justice and mercy.

Evolving the Standard of Evidence: From Eyewitnesses to Forensic “Witnesses”

As time progressed and human knowledge expanded, especially in the realms of science and technology, Islamic legal thought faced new questions: Can modern forensic evidence substitute for physical eyewitnesses? Does insisting on exactly “four male eyewitnesses” in all circumstances serve justice in the 21st century, or could it sometimes undermine it? Contemporary scholars, building on the intents discerned by classical jurists, have largely concluded that the principle behind the Quran’s evidentiary rules must be preserved, even if the means change. The essence of the four-witness requirement was to ensure certainty of guilt (hence preventing punishment of the innocent) and to protect the vulnerable from false charges. Today, we possess new “tools of truth” that can often meet or exceed the certainty provided by human witnesses. It would be contrary to the Quran’s own objectives to ignore these tools.

Forensic science has provided what one scholar calls “the silent witness of truth”. For example, DNA evidence can identify perpetrators of sexual crimes or establish paternity with a reliability impossible in the past. A single drop of blood, a strand of hair, or other genetic material left at a crime scene can now speak with near-certain accuracy, pointing to one individual out of millions. As the commentary notes, “Where 7th-century Arabia had no concept of forensic proof, 21st-century technology can often provide near-certain proof of sexual crimes or paternity. DNA evidence is one such game-changing tool. If, for example, DNA from a rape kit matches the accused, this can be more conclusive than multiple eyewitnesses.”. Likewise, video surveillance (CCTV) can capture acts in progress, and medical examinations can corroborate sexual assault. These forms of evidence were unimaginable to the early Muslim community, but their spirit – the Quran’s call for clear proof – arguably encompasses any reliable proof of the truth. Indeed, the Arabic term bayyina in Islamic law refers to clear evidence, and classical jurist Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya argued that “bayyina” in the Quran encompasses anything that elucidates the truth, not just oral testimony. In that sense, a DNA match or a fingerprint is a “witness” – one that does not forget, lie, or succumb to pressure.

This evolution in understanding is reflected in modern Islamic legal opinions and reforms. Many contemporary jurists affirm that rapists can be convicted on the basis of strong forensic or circumstantial evidence even without any eyewitnesses, since the four-witness rule “applies only to the hadd punishment in case of adultery.”. As one fatwa (religious verdict) by Sheikh Faraz Rabbani (echoing renowned jurist Mufti Taqi Usmani) clarifies, Islam does not demand an impossible burden of proof from a rape victim – rather, “the spirit of the law is to require proof beyond reasonable doubt, not necessarily four human eyewitnesses.” If DNA tests, medical reports, or other evidence yield that certainty, they fulfill the Quranic criterion of proof. This view is not a modern novelty but a continuation of the Sharia’s inner logic: even centuries ago, scholars implicitly acknowledged non-witness evidence in some cases. For instance, classical courts treated pregnancy in an unmarried woman with no husband as prima facie evidence of zina – unless she claimed rape or coercion, which would then be investigated separately. They also accepted physical signs of struggle or a victim’s cries for help (known as istighatha) as supporting evidence that could exonerate a woman who claimed rape and help implicate the assailant. In essence, the aim was always to get at the truth of the matter and uphold justice, using the best evidence available.

In the modern period, this flexibility has only grown. Consider the realm of paternity testing: classical Islamic law had an institution called qiyāfa (physiognomy), where experts would attempt to determine lineage by physical resemblance – a very inexact science by today’s standards. Now, with genetic testing, we can determine parentage with near-100% accuracy. Recognizing this, a 2002 ruling by the Muslim World League’s Fiqh Council acknowledged that DNA testing is “an effective scientific method, yielding near-certain results” for verifying lineage and can be used to support or even override weaker traditional proofs in paternity disputes. In other words, a scientific breakthrough is being treated as a modern equivalent of evidence, integrated into Sharia procedures. Similarly, courts in many Muslim-majority countries today admit DNA evidence in rape cases and other crimes. After painful experiences under rigid laws, countries like Pakistan undertook legal reforms: Pakistan’s notorious Hudood Ordinance (1979) had initially misclassified rape under zina, requiring four witnesses – but in 2006, the law was changed to treat rape as a distinct crime provable by forensic and circumstantial evidence, moving it out of the zina framework. This reform was essentially a return to classical distinctions and an embrace of modern proof: it acknowledged that applying the letter of Quran 24:4 to rape cases was a mistake that led to injustice, and that justice demanded using “any proof that establishes guilt with certainty”. Today, there is broad consensus among Islamic scholars that the hadd of zina does not apply to rape victims at all, and rapists should be punished by whatever evidence convinces the court of their guilt. Even bodies that were initially cautious, such as Pakistan’s Council of Islamic Ideology, have conceded that DNA can serve as supporting evidence (they once hesitated to accept it as sole proof, citing concerns of lab errors, but they do allow it alongside other proofs). Meanwhile, in practice, many rapists are convicted under taʿzir (discretionary punishment) when the strict hudud standard isn’t met, ensuring they are penalized rather than going free on a technicality.

The trajectory is clear: Islamic law is not static; its core values of justice and protection can be upheld through new means. Scholars like the late Fazlur Rahman have articulated a guiding method for such adaptation, known as the “Double Movement” theory. This approach involves first going back to the time of revelation to discern the general principle or intent behind a specific ruling, and then returning to the present to apply that principle in the contemporary context. In the case of Quran 24’s four-witness rule, Movement 1 shows the principle was “protect the vulnerable (like chaste women) from slander, ensure a high bar for intrusion into private lives, and guarantee certainty before punishment.” Movement 2 then asks how to achieve that same principle today. The answer has been that to protect the vulnerable today (e.g. rape victims from injustice), we must treat reliable forensic proof as the new gold standard of evidence. In Rahman’s words, “to maintain the means when it defeats the end is to worship the procedure rather than the Lawgiver.” Insisting on exactly four eyewitnesses in an age of DNA and video, especially in situations the Quran’s law was never meant to address (like rape), would actually invert the purpose – it would shield perpetrators and harm victims, thus “defeating the end (justice) for the sake of the means.” As one writer put it bluntly, “To demand four eyewitnesses to a rape is to misunderstand the Quran’s intent, ignore Islamic legal tradition, and weaponize scripture against the violated. That inversion is injustice (ẓulm).” The Quran came to eradicate ẓulm, not to create it. Therefore, nearly all scholars agree that clinging to a literalist enforcement of the four-witness rule in the face of clear scientific evidence is a distortion of Islamic law, not a defense of it. The Maqāṣid al-Sharīʿa (objectives of Islamic law) framework supports this stance, prioritizing the preservation of life, honor, lineage, intellect, and property over any rigid proceduralism. If DNA and other proofs better serve those God-given aims in our era, then they are not just permissible – they are mandated by fidelity to the Sharia’s spirit. Indeed, “if DNA provides justice, it is the Law of Allah,” to paraphrase Ibn Qayyim.

In sum, the understanding of what constitutes valid evidence in Islamic law has expanded with scientific progress, much as it has in secular legal systems. The four-witness rule remains in the Quran as a warning against careless accusations and a protection of private honor, but its implementation today is mediated by context and by reason (ijtihad). The result is that the essence of the Quranic law – certainty of truth, protection of the innocent, punishment of the guilty – is preserved even as the form of evidence shifts from the spoken word to the “silent testimony” of genetics and technology. This adaptive continuity is not a break from tradition; rather, it is in line with how the best of Islamic jurisprudence has always operated. As one modern commentary beautifully summarized: “The seventh-century requirement of four eyewitnesses achieved the Quran’s aim of practically nullifying false charges; the twenty-first-century incorporation of forensic evidence aims to achieve that same aim – certainty in establishing guilt and innocence – through the best God-given tools we have. Far from being a departure, this is a fulfillment of the Quran’s ethos in a new context.” To put it simply, the light of truth that Surah An-Nur seeks remains the same, even if the lanterns we use to shine that light have advanced with time.

Contextualizing Quranic Punishments: Adultery, Slander, and Theft

Just as the evidentiary rules of the Quran must be understood in context, so too must its prescribed punishments (hudud) be applied with an eye on their purpose and the welfare of society. The Quran outlined a few specific penalties for certain grave offenses: notably, 100 lashes for adultery (zina) as stated in Surah An-Nur 24:2, 80 lashes for unfounded accusations of adultery (slander, or qadhf) in 24:4, and amputation of the hand for theft in Surah Al-Ma’idah 5:38. These punishments have often been a focal point of debate, especially in modern times – sometimes condemned as cruel by outsiders, and at other times championed as divine mandates by revivalists. A close look at Islamic tradition, however, reveals a nuanced reality: these punishments were meant to uphold certain fundamental values, and their enforcement was deliberately hedged with conditions to prevent injustice. The spirit of the law was always more than blind retribution; it aimed at deterrence, moral seriousness, and social welfare – and it often incorporated mercy by making the penalties hard to implement in doubtful cases. Understanding this helps us see why applying the same principles in today’s context might mean using different methods to achieve the Quran’s aims.

Let us consider each of these punishments in turn:

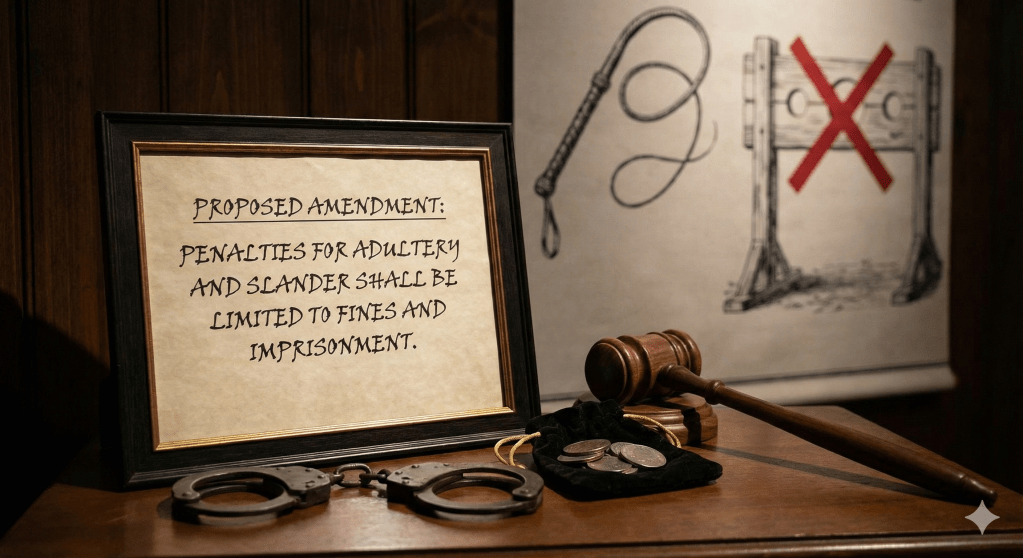

- Adultery (Zina) – 100 Lashes: The Quran’s stance on extra-marital sex is uncompromising in moral terms – it unequivocally forbids zina and regards it as a serious offense against family integrity and social morality. The hadd punishment of public flogging (100 lashes) for unmarried offenders was meant to serve as a strong deterrent in a small, close-knit community where such behavior threatened the nascent social order. Classical scholars like Al-Qurtubi noted that the Quran’s injunction “let not compassion for them keep you from carrying out Allah’s law” (24:2) reminded judges not to be swayed by the offender’s status or emotional appeals in cases of proven guilt. Yet, in practice, implementing this punishment was exceedingly rare – and that was by design. The evidentiary bar for zina was, as we saw, set so high (four witnesses to the act) that convictions were almost nonexistent unless the offenders shamelessly committed adultery in public or confessed voluntarily. In fact, Islamic law encouraged personal repentance and discouraged exposing sins; many reports indicate that if a person came to the Prophet confessing zina, he would initially turn away or try to avoid implementing the punishment, giving the person a chance to retract their confession. This demonstrates that the true goal was moral reform and deterring open immorality, rather than inflicting the physical punishment per se. Moreover, the Prophet’s saying “avoid hudud punishments in cases of doubt” became a legal maxim – meaning if there was any ambiguity in evidence, the fixed penalty would be waived. In classical times, if zina was not provable by the strict criteria, a judge could impose a lesser disciplinary penalty (like a discretionary lashing or reprimand) or simply advise repentance, thereby upholding the value of chastity without unjustly penalizing someone. Modern implications: The principle here is that society must strongly discourage sexual exploitation and protect the sanctity of the family, but also emphasize personal repentance and privacy. In a contemporary context, many Muslim jurists argue that if the social circumstances are such that public floggings would do more harm than good (e.g. undermine the objectives of justice or cause sensationalism without truly preventing sin), authorities can employ alternative penalties or measures that achieve deterrence. For instance, a legal system might treat adultery as a serious offense (where it’s also a violation of marital contracts), punishable by prison or fines rather than lashes, on the reasoning that the form of punishment can change as long as the weight of disapproval remains. The example of some countries today is telling: even those that formally have hudud laws often find ways not to apply the maximum punishment. One study of Saudi Arabia in the early 1980s found that out of 659 confirmed cases of fornication or adultery, not a single person was stoned to death (the classical hadd for a married adulterer) – instead, nearly all received lesser sentences because ambiguities or lack of absolute proof prevented the hadd. This aligns with a historical pattern: during five centuries of Ottoman rule, records show only one instance of a rajm (stoning) execution in Istanbul, whereas in contrast, early modern Europe and America saw dozens of executions for sexual crimes. Thus, the Muslim world traditionally treated hudud for zina as real but rarely actionable – a lofty standard that hovers more as a warning than a routine punishment. The changing context today – where moral lapses are private matters and the state’s role in policing them is viewed differently – suggests that emphasizing the spirit (condemn the wrongdoing, encourage repentance, protect society from public indecency) might not require literal flogging. What remains non-negotiable is that false accusations of such conduct are utterly intolerable, as the Quran’s pairing of verse 24:2 with 24:4 indicates; modern defamation and “revenge porn” laws, for instance, carry forward that ethos of protecting individual honor, albeit through different legal instruments.

- False Accusation (Qadhf) – 80 Lashes: The punishment of 80 lashes for unproven accusations of adultery underscores how seriously Islam takes an individual’s reputation and dignity. In many ways, this is the mirror image of the zina law – it is a hudud penalty aimed at slanderers. The intent, both classical and contemporary scholars agree, is to strongly discourage character assassination and guard the integrity of the community’s moral climate. In the Prophet’s society, where honor was paramount and communal ties strong, a false allegation could be ruinous or even lead to tribal conflict. Thus the Quran came down very hard on the slanderers of ʿAisha, and by extension set this law for all Muslims: anyone who accuses a chaste woman or man of adultery without four witnesses is to be publicly flogged and marked as untrustworthy. This provided a kind of social vindication for the innocent, turning the tables against those who would spread rumors. Over time, Muslim jurists again ensured that this punishment was only applied when clearly deserved – if, for example, a person tangentially made a remark that could be construed as accusation but wasn’t explicit, or if there was any uncertainty in what was said, the hadd would be averted by interpreting it as something lesser. The Prophet and companions were very cautious in this regard, preferring that a potential slanderer retract or be pardoned if possible, rather than immediately inflict 80 lashes, unless the case was egregious. In the modern world, while we may not see public floggings for slander, the principle survives in laws against libel, defamation, and the malicious spreading of unverified allegations – areas where Islamic ethics would encourage even stricter moral responsibility given the viral nature of rumors on social media. Today a person’s “honor” can be destroyed globally with a few clicks, which makes the Quran’s warning “and do not accept their testimony ever again” (24:4) sound prescient: someone proven to deliberately malign others’ honor should lose credibility in society. Thus, the core principle is as relevant as ever. A Muslim-majority legal system informed by Quranic values might impose hefty fines, social service, or imprisonment for proven slander or revenge pornography, etc., instead of lashes – a change in form, not in spirit, aligning with contemporary legal practice yet rooted in the Quran’s severe view of slander.

- Theft (Sariqa) – Amputation of Hand: Perhaps the most debated hudud punishment in modern discourse is the amputation of the thief’s hand as per Quran 5:38 (“As for the thief, male or female, cut off their hands as a recompense for what they have earned – a deterrent from Allah”). In its original context, this punishment delivered a clear message about protecting private property rights in a society where theft could easily undermine social stability (there were no banks or insurance; a theft could mean life or death for one’s family). It was also a visibly shaming penalty – marking the criminal and preventing easy recidivism (a handless thief could not stealthily steal again), which served as a public deterrent. Yet, Islamic law has never been as cut-and-dry on this matter as outsiders might think. The jurists defined such a narrow set of conditions for a theft to merit amputation that it effectively applied only to a gross, unmitigated act of theft by a competent thief under no duress. For example, property of a certain minimum value had to be stolen (hadith specifies over a quarter dinar or three dirhams; roughly equivalent to something of significant worth); it had to be stolen secretly from a secure location (snatching in public or during a violent robbery was categorized differently, often more severely, whereas stealing from an open/unsecured place didn’t meet the bar); the thief had to be sane, adult, not starving or in desperate need, not stealing as an act of warfare or rebellion, and not stealing something trivial or ambiguous in ownership. The list of exceptions is extensive – classical jurist Imam al-Subki listed dozens of items and scenarios that would not trigger the hadd: stealing any food item, fruits, public property, items of extremely low value, certain animals, etc., or theft during famine conditions, or from a close relative, and so on, would all be exempt. Additionally, two reliable witnesses to the theft were required (or a voluntary confession), similar to other hudud, and any procedural doubt could invalidate the punishment. The second Caliph Umar famously suspended hand amputation in a year of famine so that thieves driven by hunger would not be punished. And as one medieval jurist quipped, “it is not permissible to carry out hudud without the probability of some benefit” – meaning if a particular execution of the law would serve no positive purpose (for example, chopping the hand of a starving person likely to turn them into a lifelong beggar), it should be halted. Historical records suggest that actual amputations were exceedingly rare. Observers traveling in the Muslim world centuries ago noted that they hardly ever encountered the penalty being applied; one 19th-century account from Egypt remarked that the hadd for theft had not been carried out in living memory. More recent analyses confirm this rarity: in Saudi Arabia, for instance, between 1980–1983 only 2 out of 4,925 convicted theft cases resulted in hand amputation – the rest received lesser sentences at the judge’s discretion. This means over 99.9% of thieves were dealt with by taʿzir penalties (fines, imprisonment, flogging, etc.) rather than the maximal hudud. Similarly, in that period, out of 659 proven cases of zināʾ, none ended in stoning. These figures illustrate a consistent pattern: the hudud punishments were designed as a potent deterrent and a legal upper bound, but the system actively worked to avoid reaching that upper bound unless absolutely necessary (i.e., in the clearest, most shocking cases). The wisdom behind this is often elucidated by scholars: “stringent laws which God’s mercy has made almost impossible to apply exist primarily to remind people of the enormity of the sins”. In other words, the law serves an educative and moral function far more than a frequently operational one. Modern implications: The underlying values in the case of theft are security of property, justice for victims, and deterrence of criminality. A modern Islamic legal framework could argue that these aims might be better served through modern penal practices (incarceration, rehabilitation programs, restitution to victims) especially in complex societies where socio-economic factors play into crime. Some contemporary Muslim thinkers interpret “cut off their hands” metaphorically as cutting off the means or opportunity to steal – for instance, through imprisonment that physically restrains the thief, or through social welfare that removes the desperation that leads to theft. While mainstream scholarship still acknowledges the verse’s literal historical application, there is an understanding that public interest (maslaha) and the objectives of justice can warrant a moratorium or alternative sentencing in present circumstances. The fact that the second Caliph and many after him suspended hudud in various situations is often cited as precedence for modern governments to, for example, halt amputations until society fulfills certain conditions (e.g., eliminating extreme poverty and ensuring everyone’s basic needs – a condition some classical scholars argue is necessary before the theft punishment can be fairly enforced). Thus, applying “similar principles of changing context” here means asking what outcome the Quranic punishment was meant to achieve and whether that outcome is achievable (or better achievable) by different means today. If the spectacle of hand amputation in a modern context would generate horror, backlash, or even sympathy for the criminal – thereby undermining its deterrent effect and perhaps hardening the criminal further – one could argue it fails the benefit test that Al-Kasani mentioned. For example, many Muslim-majority countries for decades have handled theft primarily through prison terms and fines, reserving the amputation technically on the books but virtually never using it. This doesn’t mean denying the scripture, but rather emulating the Prophet’s and Sahaba’s demonstrated practice of being extremely cautious and selective in applying hudud. Any modern Islamic legal reform would likely continue to keep such punishments in extreme reserve, focusing instead on addressing the root causes of theft and ensuring that punishments, when needed, rehabilitate rather than solely retribute.

In all these cases – adultery, slander, and theft – we see a common thread: the Quranic law was as much about upholding certain moral and social norms as it was about punishing crime. The changing context from a small 7th-century community to today’s globalized, institutionalized societies means that the forms of preserving those norms can evolve. Justice, in the Islamic conception, isn’t served by simply replicating historical punishments in a vacuum; it is served by fulfilling the objectives those punishments embodied. And Islamic jurisprudence has long provided the tools (through ijtihad, maslahah (public interest), maqasid, etc.) to adjust the applications while staying true to divine intent. As evidence of this continuity: throughout Islamic history, judges frequently opted for alternative punishments (taʿzir) and employed legal stratagems to avoid imposing hudud whenever circumstances were not ideal. This was not viewed as neglecting God’s law, but rather as honoring its overarching intent – the Prophet’s famous instruction to “ward off hudud by ambiguities” was treated itself as part of God’s law. Modern Islamic legal thinkers therefore argue that we should not approach the Quran’s penal laws with a surface literalism that ignores context. Just as we have incorporated forensic science to meet the evidentiary spirit of the law, we can also incorporate modern penal philosophies (like rehabilitation and restorative justice) to meet the corrective and deterrent spirit of the law. The goal remains what it always was: protect society’s core values (faith, life, intellect, lineage, property) and do so with justice and compassion. Sometimes that may mean being firm – as the Quran was firm in principle – and other times being forgiving – as the Quran was keen to forgive those who repent (Quran 5:39 follows the theft verse by extolling repentance and God’s mercy). A contextual application does not negate the texts; it illuminates them in our lived reality, keeping their Nur (light) shining in guidance rather than treating them as harsh relics.

Thematic Epilogue: Balancing Text and Intent in the Pursuit of Justice

The journey of the four-witness rule from Medina’s dusty streets to the DNA laboratories of today is emblematic of a broader truth in Islamic law: God’s guidance is timeless in principles, yet dynamic in application. The opening verses of Surah An-Nur weave together themes of moral discipline, justice, and social well-being that resonate across ages. They declared inviolable principles – the sanctity of marriage, the gravity of adultery, the protection of individual honor, the necessity of truth in court – but they also embedded a flexibility by coupling every stern rule with a compassionate hedge (severe punishment but requiring stringent proof; allowing the accused an out through oaths; etc.). This duality was not accidental; it was divine wisdom manifest even then, teaching us that law must be imbued with ethics and mercy to truly be just.

Over centuries, as Muslims encountered new situations, they did not always get it right – there were periods of over-literalism and rigidity that caused suffering, just as there were, conversely, instances of undue laxity. But the enduring trend, among those deeply learned, was a return to the Prophet’s own practice: uphold the spirit even at the expense of the literal form when the two seem to conflict. “Fundamentalists who freeze the law in literal amber,” one commentator writes, “miss that the Quran came as ‘light upon light’ – it provided light (guidance) for a specific situation, but also the light of reasoning to apply its morals afresh in each age.” If we treat the Quran’s legal verses as a map, we must remember what the terrain is that they cover – human welfare, justice, godliness. When the terrain changes (new technologies, new social structures), the map must be read with understanding, not tossed aside nor clung to mindlessly. To prefer the map over the terrain is to lose one’s way.

The evolution of the concept of “witnessing” – from four righteous men standing at the scene of a crime, to the genetic code testifying in a lab – beautifully illustrates that the form can change while the essence remains. In the Prophet’s Medina, the community’s honor “hung on the fragile thread of human speech”, so four witnesses were like fortresses of truth against the gale of gossip. Today, truth has more tools at its disposal; God’s name Al-Ḥaqq (The Truth) is reflected in the new signs He has unfolded in creation – the microscopic evidence that was always there, awaiting human discovery. Embracing these signs is not a departure from faith; it is an act of faith, an appreciation that God does not bind justice to the limitations of one era. In Islam’s holistic vision, Justice (`adl) is indeed a supreme value – the Quran tells us that all Messengers and scriptures were sent “so that people might uphold justice” (57:25). Thus, any interpretation of scripture that leads to clear injustice is ipso facto suspect. This is why scholars stress that if a literal reading of a Quranic rule yields cruelty or inequity in a new context, we must have misread something. The fault is in our understanding, not in the revelation, which came to promote welfare. Time and again, Islamic history showed sages choosing to err on the side of mercy, to delay or forego a hadd if there was any uncertainty – and uncertainty only increased in new circumstances, which rightly led to caution or reinterpretation.

In applying Quranic punishments today, the changing context argument does not imply a free-for-all to erase divine law; rather, it calls for earnest, scholarly engagement to achieve the same objectives the Quranic law intended, using the most effective and just means available. Cutting off a hand in a tribal setting where that person’s clan would still support them might have been a strong deterrent; in a modern urban setting, the same act could create a destitute, embittered individual – so perhaps long-term imprisonment (which was not a viable or common option in seventh-century Arabia) now better secures both society and the offender’s chance to reform. Public flogging of adulterers might have shamed them into repentance and scared others away from sin in a culture deeply averse to such behavior; in a hypersexualized global culture, that public shaming might either not carry the same moral weight or might violate contemporary notions of human rights, potentially bringing Islam into disrepute without significantly curbing the sin – thus other measures to strengthen family values and punish egregious cases (like legal consequences for adultery in divorce or custody proceedings) could be more beneficial. These are debates ongoing in Muslim scholarship, but the key is that Muslims must not lose sight of the higher goals (maqasid) behind the laws: protecting faith, life, intellect, lineage, and property, and above all establishing justice.

When we realize that, we see the hudud not as isolated harsh edicts, but as part of a moral-spiritual tapestry aiming for human betterment. And we see the role of human understanding and context in applying them rightly. The great jurist Ibn al-Qayyim stated, “Wherever the signs of justice appear, there lies the Sharia of Allah.” Justice is the end, legal rulings are the means. The Quran’s first audience needed one set of means; subsequent ages might need others. By remaining true to the Quran’s spirit, we ensure that its light (nur) continues to shine guidance rather than cast shadows of rigidity.

In conclusion, the evolution in understanding the four-witness rule and the discussion on Quranic punishments teach a timeless lesson: law in Islam is not a petrified code; it is a living guidance meant to secure goodness (ma’ruf) and prevent harm (munkar) in society. The four witnesses of the 7th century were a means to a just end; the “silent witness” of forensic science in the 21st century is a means to the same end. The form changes, but justice endures. Likewise, the punishments prescribed in the Quran set a moral vision – of honoring marriage, truthfulness, property rights, and social responsibility – but the way we give effect to that vision can adapt so long as we do not compromise those values. Clarity, as the Quran promised its verses would provide, “is not only in the letter but in grasping the purpose.” By embracing both the letter and the spirit – by punishing only the truly guilty, by fiercely guarding the innocent from false blame, by promoting repentance and reform, and by never mistaking cruelty for piety – Muslims ensure that the radiance of God’s law illuminates hearts and societies in every age. In that enlightenment, we find the true message of the Quran: justice tempered with mercy, law enriched by compassion, and humanity dignified under God’s guidance.

The past and present thus converse in the realm of Islamic law. Our predecessors gave us noble principles and cautionary tales; our task is to carry that trust forward. As we navigate new challenges, we stand on the shoulders of giants – and under the shade of divine revelation – striving always to let ethical intent triumph over mechanical form. This is how a medieval rule about witnesses can transform into a modern rule about DNA, and how an ancient punishment can be rethought through modern lenses – not as a rebellion against God, but as a renewed commitment to serve His overarching Will: a just and moral order on Earth.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment