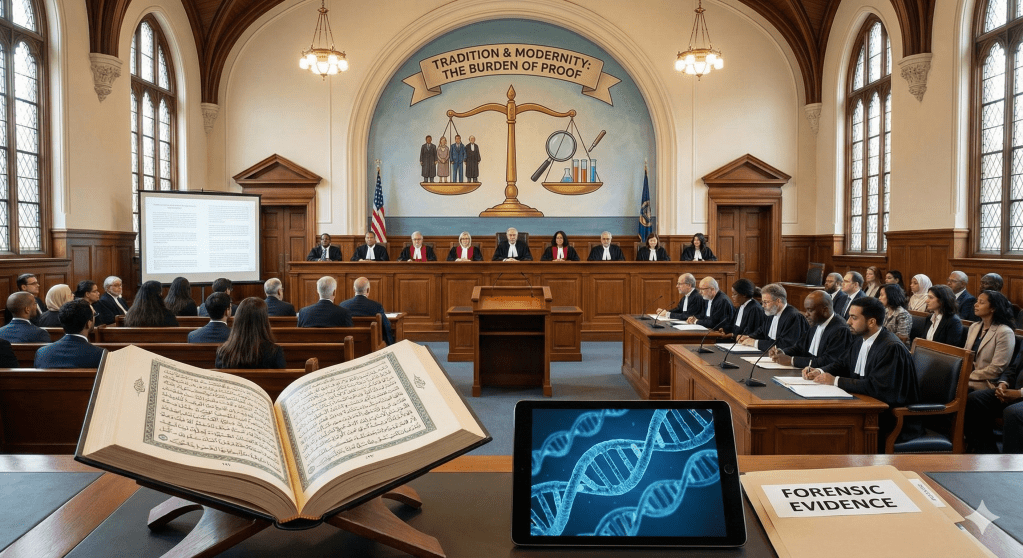

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

This report provides an exhaustive legal, historical, and sociological commentary on Surah An-Nur (24:1-6), focusing on the profound tension between classical evidentiary requirements—specifically the four-witness rule (shahada)—and the imperatives of modern justice. Historically, the revelation of these verses served a radical protective function in 7th-century Medina, specifically designed to shield women from slander (qadhf) during the “Incident of the Ifk.” However, the contemporary transposition of these theological safeguards into statutory rape laws in various Muslim-majority jurisdictions has frequently resulted in a miscarriage of justice, where the burden of proof originally intended to protect the accused is weaponized against victims of sexual violence. This analysis argues that the “four-witness” requirement was a context-dependent mechanism for public decency and honor, not an immutable barrier to prosecuting violent crime. By utilizing the Maqasid al-Shari’ah (Objectives of Islamic Law) and methodologies such as Fazlur Rahman’s “Double Movement,” this report contends that scientific truths offered by DNA profiling and forensic biology constitute a “silent witness” that fulfills the Quranic demand for certainty (yaqin). The report advocates for the elevation of circumstantial evidence (qarinah) to the status of decisive proof in cases of rape and paternity, arguing that fundamentalist literalism in this domain constitutes a betrayal of the Quran’s ultimate objective: the establishment of justice. The report concludes that maintaining 7th-century procedural limitations in the face of 21st-century forensic capability is not an act of piety, but a facilitation of impunity.

1. Introduction: The Text, The Law, and The Crisis of Interpretation

The opening passage of Surah An-Nur (The Light) stands as one of the most legislatively dense and socially significant portions of the Quranic corpus. These verses, 24:1-6, do not merely offer moral exhortations; they establish a rigorous penal code concerning zina (illicit sexual intercourse), the severe consequences for qadhf (unsubstantiated accusation or slander), and the procedural remedy for spousal accusation known as li’an.

“This is a Surah which We have sent down and made obligatory… The woman and the man guilty of illegal sexual intercourse, flog each of them with a hundred stripes… And those who accuse chaste women, and produce not four witnesses, flog them with eighty stripes, and reject their testimony forever… And for those who accuse their wives, but have no witnesses except themselves, let the testimony of one of them be four testimonies (swearing) by Allah that he is of those who speak the truth…” (Quran 24:1-6).1

In the contemporary era, these verses have become the epicenter of a fierce, often polarizing, legal and ethical debate within the Muslim world and among scholars of Islamic law. On one side of this divide stands a literalist jurisprudence, often codified in modern state statutes, that insists on the procedural ritualism of four male eyewitnesses to establish sexual crimes, regardless of the physical reality or the nature of the offense (consensual vs. coercive). This approach, rooted in a static reading of Fiqh texts, argues that the divine law is immutable in its form, and therefore, the procedural requirements laid down in Medina must be replicated exactly in modern courtrooms.3

On the other side stands a reformist, Maqasid-oriented approach which argues that sticking to the 7th-century procedural mechanism (eyewitnesses) while ignoring 21st-century evidentiary certainty (DNA/forensics) defeats the very purpose of the law.5 This perspective suggests that the four-witness rule was a protective shield for the vulnerable, which has paradoxically been transformed into a sword used against victims of sexual violence.

1.1 The Semantic Field: Zina, Qadhf, and the Absence of Ightisab

It is critical to establish a foundational linguistic reality: the Quran in 24:2 uses the term Zina, which classically implies a reciprocal, consensual act of illicit intercourse between two parties. The text in these specific verses does not address Ightisab (rape) or Zina bil-Jabr (forced zina). Classical Islamic law distinguishes rape as a crime of violence, often categorizing it under Hirabah (banditry/warfare against society) or applying the law of Ikrah (coercion), which removes the culpability of the victim entirely.3

However, the modern conflation of these distinct categories—treating rape as merely a subset of adultery requiring the same evidentiary standard—has led to catastrophic legal outcomes. This is most visibly seen in the application of the Hudood Ordinances in Pakistan (1979) and similar statutes in Northern Nigeria, where a failure to provide four witnesses for a rape accusation could be inverted into a confession of zina by the victim, as she has admitted to the sexual act without proving the coercion to the satisfaction of the literalist court.8

This report posits that such interpretations are a gross deviation from the Quranic intent. The requirement for four witnesses was established to make proving consensual adultery nearly impossible, thereby protecting privacy and reputation. Applying this “impossible standard” to rape, a crime that demands prosecution and public safety, turns the divine wisdom on its head.3

1.2 The Crisis of Epistemology

The debate is fundamentally epistemological: What constitutes “proof” (bayyinah) in Islam? Classical jurisprudence relied heavily on Shahada (oral testimony) because, in a pre-scientific age, the character of the witness was the closest proxy to truth available. Today, forensic science offers Yaqin (certainty) that transcends the fallibility of human memory or honesty. The tension lies in whether the Shari’ah honors the form of the proof (four men speaking) or the substance of the proof (certainty of the event).11

2. The Socio-Historical Matrix: The Incident of Ifk and the Rationale of Protection

To understand the severity of the four-witness requirement, one cannot view the text in a vacuum. One must examine the Sabab al-Nuzul (Occasion of Revelation). The verses of Surah An-Nur did not descend merely as abstract law; they were a divine intervention during a moment of profound communal trauma known as the “Incident of the Ifk” (The Great Slander).13 This context is not incidental; it is the key to decoding the “Illah” (legal rationale) of the witness requirement.

2.1 The Incident of the Ifk: A Community in Crisis

The incident occurred following the expedition of Banu al-Mustaliq in the 6th year of Hijrah. Aisha bint Abu Bakr (RA), the beloved wife of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), was accidentally left behind at a campsite. She was eventually found and escorted back to Medina by a companion named Safwan ibn al-Mu’attal, who led her camel while walking on foot.14

Upon their arrival in Medina, the optics of the Prophet’s wife returning alone with a man were seized upon by the “Hypocrites” (Munafiqun), a political faction within Medina led by Abdullah ibn Ubayy. They sought to destabilize the Muslim community by attacking the honor of the Prophet’s household. Rumors spread like wildfire, accusing Aisha of infidelity.15

The consequences were devastating. The community was fractured between those who defended Aisha and those who indulged in the gossip. The Prophet himself was plunged into weeks of personal anguish, suspended between his trust in his wife and the rampant social pressure. He consulted his companions, finding no clear evidence. Aisha fell gravely ill, unaware of the rumors until her recovery, at which point she was devastated.13

2.2 The Delay of Revelation and the Divine Reprimand

For nearly a month, the heavens were silent. This delay served a pedagogical purpose: it exposed the fragility of human reputation and the destructive power of the tongue. When the verses (24:11-20) finally arrived, they did not merely exonerate Aisha; they reprimanded the community for entertaining the slander without proof.

“Why then, did not the believers, men and women, when you heard it (the slander) think good of their own people and say: ‘This is an obvious lie’?” (Quran 24:12).13

The revelation established that the default state of a believer is innocence and honor (Hurmah). To violate that honor requires an overwhelming burden of proof.

2.3 The Four-Witness Rule as a Shield, Not a Sword

It is in this context that the requirement for four witnesses (Quran 24:4) must be understood. It was not introduced to facilitate sexual impunity or to make it hard to punish criminals. Rather, it was introduced to weaponize the burden of proof against the slanderer.

In the context of 7th-century Arabia:

- Privacy (Satr): Houses were simple; privacy was fragile. The law sought to prevent neighbors from spying or malicious actors from destroying reputations based on suspicion.

- The Standard of Certainty: To produce four eyewitnesses who saw the act of penetration “like a kohl stick in a kohl container” (a classical metaphor) required the act to be so flagrant and public that it was no longer a private sin but a public rebellion against decency.

- Punishment for Slander: The verses decreed that if an accuser brought three witnesses, but failed to find a fourth, all three would be flogged with 80 lashes for Qadhf and their testimony rejected forever.2

This high bar was a protectionist logic. It was designed to shield women from being blackmailed, defamed by rejected suitors, or targeted by political enemies like Abdullah ibn Ubayy.

The Modern Distortion:

The tragedy of modern literalism is the inversion of this logic. Today, when this high bar—meant to shield women from slander—is applied to rape victims seeking justice, the shield is transformed into a sword against the victim. A woman who cries “rape” is not a slanderer spreading gossip; she is a victim seeking redress. Yet, by applying the Qadhf logic to her cry for help, literalist courts have historically punished her for failing to meet a standard designed for a completely different sociomoral context.3

3. The Jurisprudential Divide: Zina, Rape, and the Evolution of Evidence

The application of Surah An-Nur has evolved through centuries of Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). A critical fracture exists between the nuanced approaches of classical jurists and the rigid statutory literalism seen in some modern post-colonial states.

3.1 Classical Fiqh: The Distinction between Hadd and Tazir

Classical jurists (of the Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali schools) generally operated with a dual-layered legal system regarding evidence.

- The Hadd Layer: For the maximum, fixed punishment (Hadd) of lashing or stoning to be applied, the Quranic requirement of four male witnesses was absolute. This was a theological boundary set by God. If the witnesses were not present, the Hadd could not be executed.

- The Tazir Layer: However, this did not mean the accused went free. Judges (Qadis) possessed broad discretion to apply Tazir (discretionary punishment) based on lesser evidence, such as circumstantial proof (Qarinah), fewer witnesses, or the judge’s own knowledge. A rapist could be imprisoned, flogged, or exiled based on strong circumstantial evidence, even if four witnesses were lacking.8

3.2 Rape as Hirabah (Banditry) vs. Zina

A vital distinction often missed by modern fundamentalists is the categorization of rape.

- The Maliki View: The Maliki school, in particular, was robust in distinguishing rape (Ghasb) from Zina. They viewed forced sexual assault as a form of Hirabah (warfare against society/banditry). Under Hirabah, the evidentiary standards are different; the focus is on the violence and the threat to public safety. The punishment could be death, crucifixion (public display), or exile, derived from Surah Al-Ma’idah (5:33), not Surah An-Nur.

- Coercion (Ikrah): All schools agree that a woman who is coerced is innocent of Zina. The debate historically centered on how she proves coercion. The Hanafis were stricter, requiring signs of struggle or screaming, while Malikis were more accepting of circumstantial evidence like pregnancy in a woman known for chastity.7

3.3 The Procedure of Li’an (Spousal Accusation)

Verses 6-9 of Surah An-Nur address the specific dilemma of a husband who suspects his wife of adultery but lacks the impossible four witnesses. He cannot simply accuse her (or he would be lashed for Qadhf), nor can he remain silent and raise an illegitimate child.

- The Solution: He swears an oath four times (Li’an) invoking God’s curse upon himself if he lies. The wife can avert the punishment of adultery by swearing a counter-oath four times, invoking God’s wrath upon herself if he is telling the truth.1

- The Effect: This procedure results in the immediate dissolution of the marriage and the denial of paternity (Nafi al-Nasab). In the 7th century, this was the only way to resolve the epistemological deadlock of “he-said, she-said” regarding paternity.

- Contemporary Relevance: The persistence of Li’an as the sole method of paternity denial in some jurisdictions, even when DNA evidence proves the husband is not the father, represents a clash between procedural ritual and biological truth.21

3.4 Table 1: Divergence in Legal Categorization of Sexual Acts

| Legal Concept | Classical Hanafi Position | Classical Maliki Position | Modern “Islamized” Statutory Law (e.g., 1979 Pakistan) | Reformist / Maqasid Approach |

| Definition of Rape | Coercive Zina (Zina bil-Jabr). | Often treated as Hirabah (Violence/Banditry) or Usurpation (Ghasb). | Conflated with Zina; rape defined as “Zina against will.” | Violent crime distinct from Zina; distinct evidential rules apply. |

| Evidentiary Standard | 4 Witnesses for Hadd; Tazir possible with less. | 4 Witnesses for Hadd; Pregnancy can be proof of rape if woman claims coercion immediately. | 4 Witnesses required for maximum punishment. | DNA and forensic evidence accepted as primary proof (Qarinah Qat’iyyah). |

| Status of Victim | Not punishable if coercion proved. | Not punishable; presumed innocent if she calls for help. | If rape not proved, victim’s admission of sex could be used to prosecute her for Zina. | Victim is protected; burden of proof is on state/accuser; DNA corroborates coercion. |

| Role of Pregnancy | Not proof of Zina (possibility of coercion/doubt). | Proof of Zina in unmarried women unless she claims rape/coercion prior. | Often treated as confession of Zina if rape not proven (prior to 2006 reforms). | Proof of contact; DNA links to perpetrator. |

4. The Crisis of Modern Codification: The Statutory Failure

In the late 20th century, various post-colonial Muslim-majority states embarked on “Islamization” drives, attempting to codify Shari’ah into modern statutory law. This process often involved stripping the nuance from classical Fiqh and cementing literal interpretations into state penal codes.

4.1 The Hudood Ordinances (Pakistan, 1979)

The most prominent example is the Zina Ordinance introduced by General Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan. This law conflated Zina (consensual sex) and Zina-bil-Jabr (rape) into a single legal framework governed by the evidentiary standards of Surah An-Nur.8

- The Trap: To prove the maximum offense of rape, a woman was required to produce four pious male eyewitnesses to the act of penetration. This is practically impossible.

- The Backfire: If a woman reported a rape but failed to produce four witnesses, the court could effectively acquit the rapist. However, by reporting the rape, the woman had medically or verbally admitted to engaging in sexual intercourse. Since she failed to prove “coercion” (due to lack of witnesses), the court could then charge her with consensual Zina based on her own confession.9

- Case Studies: Cases like that of Safia Bibi (a blind girl raped by her employer and his son, subsequently sentenced to lashes for Zina while the rapists were acquitted for lack of evidence) and Jehan Mina shocked the global conscience. These cases demonstrated how the “protectionist” verses of the Quran were inverted to persecute the very demographic they were revealed to protect.10

4.2 The Nigerian Experience

Similarly, following the expansion of Shari’ah penal codes in Northern Nigeria (starting with Zamfara in 1999), the distinction between pregnancy as evidence of Zina versus evidence of rape became a flashpoint.

- Amina Lawal Case: Amina Lawal was sentenced to stoning for Zina after becoming pregnant post-divorce. The defense successfully used the “sleeping fetus” doctrine (a classical Maliki concept) to cast doubt (Shubuhat) and avert the punishment. While this saved her life, it relied on a biological impossibility (a fetus sleeping for years) rather than confronting the procedural injustice of the evidentiary system.23

4.3 The Failure of Literalism

These statutory frameworks represent a failure of Ijtihad (legal reasoning). They adopt the “form” of the Quranic text (four witnesses) while violating its “substance” (justice). By removing the judge’s discretion to use Tazir effectively and by rejecting modern circumstantial evidence, these laws created a sanctuary for predators. They illustrate the danger of “codifying” fluid juristic concepts into rigid state machinery without the safety valves of classical wisdom.8

5. The Silent Witness: DNA and Circumstantial Evidence in the 21st Century

The central thesis of this report is that modern forensic science fulfills the Quranic requirement for Bayyinah (clear proof) and Yaqin (certainty) far more effectively than human testimony, which is prone to error, forgetfulness, and corruption.

5.1 From Shahada (Testimony) to Qarinah (Circumstantial Evidence)

In classical Usul al-Fiqh, Qarinah refers to circumstantial evidence. While the majority of classical scholars were hesitant to rely solely on Qarinah for Hadd punishments (to avoid errors in capital cases), they accepted it for Tazir.

- The Evolution of Certainty: Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, a revered Hanbali jurist, argued that Bayyinah in the Quran encompasses anything that elucidates the truth, not just oral testimony. He stated that if “signs” (Amarat) provide certainty, they should be accepted.24

- Scientific Certainty: Unlike the ambiguous circumstantial evidence of the past (e.g., a vomiting woman implying pregnancy, which could be illness), DNA profiling offers a statistical probability bordering on absolute certainty (99.99%). This moves Qarinah from the realm of Zann (speculation) to Qat’ (definitive proof).

- Re-evaluating the Standard: Modern scholars argue that the “four-witness” rule was a means to an end (certainty). If a higher degree of certainty can be achieved through DNA, CCTV, or forensic biology (semen analysis), sticking to the lower standard of oral testimony is irrational.11 The “Silent Witness” of DNA does not lie, does not forget, and cannot be bribed.

5.2 Re-evaluating Paternity and the “Bed” Rule

The Prophetic maxim “The child belongs to the bed” (al-walad li-l-firash) was a rule of social stability, ensuring that children born in wedlock were legitimate unless proven otherwise.

- The Conflict: Traditionalists argue that even if DNA proves a husband is not the father, the “Bed” rule prevails to protect the child’s legitimacy.21 This leads to the absurdity of attributing a child to a man who biologically could not have fathered them.

- The Reformist View: This interpretation ignores the biological reality that Nasab (lineage) is genetic. Forcing a man to raise a child proven not to be his, or denying a child their true biological father, violates the Quranic command in Surah Al-Ahzab (33:5): “Call them by [the names of] their fathers; it is more just in the sight of Allah.”

- Rape and Paternity: In cases of rape resulting in pregnancy, DNA is the only mechanism to identify the perpetrator and exonerate the victim from accusations of Zina. Denying the admissibility of DNA in these cases amounts to suppressing the truth.11

5.3 Case Study: The “Physiognomy” Precedent

A compelling argument for DNA admissibility is the precedent of Qiyafah (physiognomy). In the time of the Prophet, experts (Qa’if) traced lineage by looking at physical similarities (feet, faces). The Prophet (PBUH) expressed joy when a Qa’if confirmed the lineage of Usama bin Zayd, whose dark skin differed from his father’s, based on the shape of their feet.21

- The Insight: If the Prophet accepted the primitive “genetic analysis” of observing physical traits, a fortiori (with greater reason), Islamic law should accept the definitive genetic analysis of DNA, which is essentially Qiyafah at a molecular level.

6. The Tragedy of Literalism: Fundamentalism vs. The Message

The fundamentalist approach to Quran 24:1-6 represents a “betrayal of the message” by adhering to the text’s surface while destroying its moral core. This literalism creates what scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl calls “ugliness”—a jurisprudence that produces results offensive to the conscience of the believer and the objective of the Shari’ah.27

6.1 The Methodological Error: Atomism

Fundamentalist interpretations often suffer from atomism—taking verses in isolation without regard for the holistic Quranic ethos or the historical context.

- Ignoring the “Illah” (Legal Ratio): The legal reason for the 4-witness rule was Satr (privacy) and Dara’ al-Hudud (averting punishment through doubt). When literalists use this rule to prevent the conviction of a rapist despite DNA evidence, they are using a rule meant to save life to effectively destroy it.12

- Spiritual Corruption: By prioritizing procedural correctness over substantive justice, literalist systems risk “spiritual corruption.” They create a society where truth is suppressed by law. As noted in the snippets, ignoring the reality of forensic truth is tantamount to injustice, which the Shari’ah abhors.5

6.2 Fazlur Rahman’s “Double Movement”

To resolve this, the methodology of modernist scholar Fazlur Rahman (d. 1988) is essential. The “Double Movement” theory posits a way to bridge the 7th and 21st centuries:

- Movement 1: Go back to the time of revelation (7th Century) to understand the principle behind the specific ruling.

- Specific Ruling: 4 witnesses required for sexual accusations.

- Principle: Protect the vulnerable (Aisha/women) from slander; establish a high bar for state intrusion into private lives; ensure certainty before punishment.

- Movement 2: Return to the present and apply that principle to the modern context.

- Modern Context: We have DNA and forensic science. Rape is under-reported and weaponized. Privacy is invaded by digital means.

- Application: To protect the vulnerable (rape victims) today, we must accept DNA as the highest form of “witnessing,” as it offers the protection and truth the original verse sought to establish. Adhering to the 4-witness rule in rape cases today actually violates the principle of protecting the vulnerable.6

6.3 The Tariq Ramadan Case: A Modern Paradox

The recent case of Tariq Ramadan, a prominent Islamic scholar convicted of rape in a Swiss appellate court, highlights this tension. While Ramadan maintained his innocence and the defense relied on the “he-said, she-said” ambiguity (reminiscent of the classical deadlock), the court relied on “testimonies, certificates, medical notes, and opinions of private experts” to overturn a previous acquittal.33

For a Muslim audience, this case underscores that religious status or procedural defenses cannot hide the reality of sexual violence. A Maqasid-based approach would argue that if the forensic and psychological evidence (modern Qarinah) points to guilt, the “Muslim” defense of requiring four eyewitnesses is invalid and morally bankrupt. Justice must be blind to status and served by truth, however that truth is arrived at.35

7. Maqasid al-Shari’ah: Preserving the “Five Essentials”

The ultimate refutation of the literalist position lies in the Maqasid al-Shari’ah (Objectives of Islamic Law). The Shari’ah aims to preserve five essentials: Faith (Din), Life (Nafs), Intellect (Aql), Lineage (Nasl), and Wealth (Mal). A ruling that violates these essentials cannot be Islamic law.

7.1 Hifz al-Nasl (Preservation of Lineage) vs. Hifz al-Ard (Honor)

- Rape: Failing to prosecute rape because of the witness requirement violates Hifz al-Nafs (Life) and Hifz al-Ard (Honor) of the victim. It prioritizes the “Honor” of the perpetrator (by shielding him via procedural technicalities) over the physical and spiritual safety of the victim.36

- Paternity: Denying DNA evidence violates Hifz al-Nasl. Lineage is a biological fact essential for identity, inheritance, and mahram relationships. Ignoring biology for the sake of a procedural oath (Li’an) undermines the very lineage the law seeks to protect. If a child is falsely attributed to a father, the laws of inheritance and marriage are corrupted.38

7.2 Justice (Adl) as the Supreme Maqasid

Scholars like Jasser Auda and Yusuf al-Qaradawi argue that Justice is the overarching objective of the Quran.

- “Indeed, We sent Our messengers with clear proofs… that the people may maintain [their affairs] in justice.” (Quran 57:25).

- Any interpretation of 24:4 that leads to manifest injustice (e.g., punishing a rape victim) is, by definition, un-Islamic. The four-witness rule was a means to justice in the 7th century. To maintain the means when it defeats the end is to worship the procedure rather than the Lawgiver.5

- The jurist Ibn Qayyim stated: “Where there are signs of justice and the face of justice appears, that is the Law of Allah and His Face.” Therefore, if DNA provides justice, it is the Law of Allah.

8. Conclusion: The Essence Must Prevail

The commentary on Quran 24:1-6 leads to an inescapable conclusion: the “four-witness” requirement is a specific, context-bound evidentiary standard designed to protect privacy and prevent slander in the case of consensual sexual conduct. It was never intended, nor should it ever be used, to grant immunity to violent predators.

The fundamentalist adherence to 7th-century forensic limitations in the face of 21st-century scientific certainty is not “faithfulness” to the Quran; it is an abandonment of its spirit.

- Rape is not Zina: It is a crime of violence (Hirabah) and must be prosecuted using all available forensic, medical, and circumstantial evidence. The witness requirement does not apply.

- DNA is a Witness: In the eyes of the Shari’ah, Bayyinah (proof) is whatever elucidates the truth. DNA evidence is a “witness” that does not lie, forget, or conspire. It supersedes oral testimony in matters of paternity and sexual contact.

- The Message of An-Nur: The “Light” of Surah An-Nur is the light of truth and transparency. To allow literalism to obscure the truth of a rape victim’s suffering or a child’s lineage is to plunge the society back into the darkness (Zulumat) of the pre-Islamic Jahiliyyah.

Thematic Epilogue

The Evolution of Witnessing

In the desert heat of Medina, the honor of a woman—and the stability of a community—hung on the fragile thread of human speech. The four witnesses were the sentinels of that era, a high wall built to keep the chaos of rumor at bay. It was a mercy, a divine barrier against the “eating of flesh” that is gossip. It was the only technology of truth available to a people whose lives were open to the sky.

But God is Al-Haqq (The Truth). He does not bind Justice to the limitations of the human eye forever. As humanity was granted the knowledge to read the code of life itself—the helix of DNA, the biology of the cell—the “witness” evolved. The sentinels are no longer just men standing in a room; they are the very cells of the body, testifying with a certainty that no tongue can twist.

To reject this new witnessing in the name of the old is to reject the unfolding signs (Ayat) of God in the universe. It is to prefer the map over the terrain. The essence of the Quranic command remains unchanged: protect the innocent, punish the guilty, and uphold the truth even if it be against yourselves. The four witnesses of the 7th century were a necessity of their time; the “Silent Witness” of science is the necessity of ours. The form changes; the Justice endures.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment