Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio summary:

Abstract

The evolution of religious and ethical thought has consistently grappled with the tension between ritual formalism and substantive righteousness. This report presents an exhaustive research analysis of Quran 2:177, universally known in the Islamic exegetical tradition as Ayat al-Birr (The Verse of Righteousness). By synthesizing classical tafsir (exegesis), contemporary theological commentary, and comparative historical analysis, this document establishes that Verse 177 serves not merely as a legal injunction but as the “Architecture of Righteousness”—a comprehensive “constitution of the Muslim soul” that integrates metaphysical belief, economic sacrifice, ritual adherence, and psychological resilience into a unified phenomenology of the “Truthful” (Al-Sadiqun).1

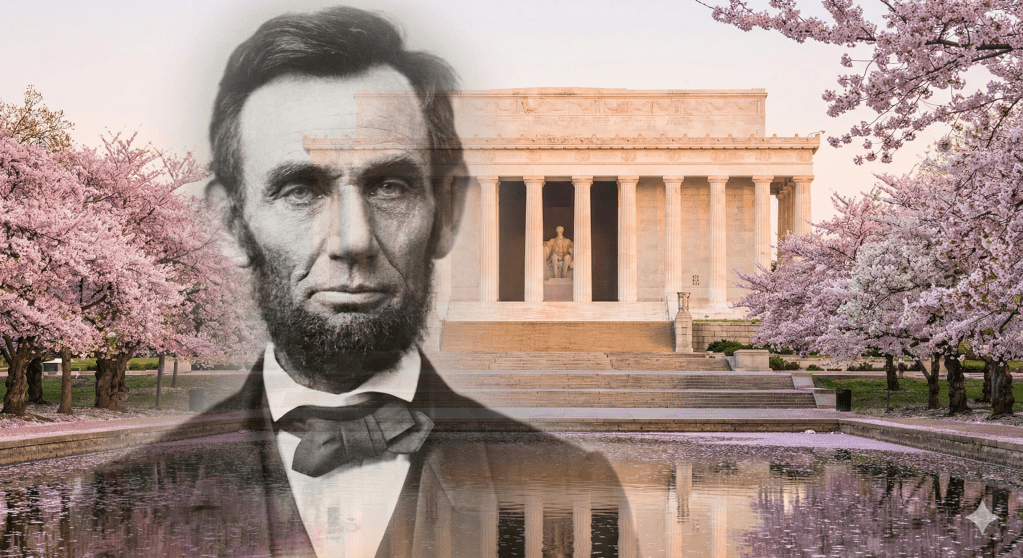

Furthermore, this report extends the theological framework of Ayat al-Birr into a comparative historical study, identifying profound resonances between the Prophetic paradigm of Muhammad (peace be upon him) and the moral leadership of President Abraham Lincoln. Utilizing the “thematic intertextuality” of the Quran—specifically connections to Surah Al-Balad, Al-Ma’un, and Al-Fajr—and the historical records of the American Civil War, the analysis demonstrates a shared “Theology of Liberation.” Both figures are identified as liberators of slaves who championed the “sovereignty of conscience” over external dogma.2 This document argues that the “Steep Path” (Al-Aqabah) of the Quran and the Lincolnian struggle for the Union represent parallel manifestations of the same universal ethical imperative: the alignment of the human will with a Divine or moral absolute that demands the dismantling of oppression and the purification of the self.

Chapter 1: The Historical Crisis and the Divine Corrective

1.1 The Geopolitical and Theological Rupture

To fully comprehend the magnitude of Ayat al-Birr, one must first reconstruct the precise historical and psychological moment of its revelation. The verse was revealed in Medina, likely during the second year of the Hijrah (migration), a period characterized by a seismic shift in the identity of the nascent Muslim community.4 This era marked the transition from the persecuted, loose coalition of believers in Mecca to a distinct socio-political entity in Medina. Central to this transition was the Tahwil al-Qiblah—the divine command to shift the direction of prayer from Jerusalem (Bayt al-Maqdis) to the Kaaba in Mecca.

This shift precipitated a “geopolitical and theological rupture” that threatened to fracture the community.1 For centuries, Jerusalem had stood as the undisputed axis of monotheistic worship. The Jewish tribes of Medina viewed the Muslims’ initial orientation toward Jerusalem as a validation of their own primacy. Conversely, the Arab polytheists viewed the Kaaba as their ancestral heritage. When the Quran commanded the shift to Mecca, it unleashed a crisis of formalism. The Jews criticized the Muslims for abandoning the “direction of the Prophets,” while the Hypocrites (Munafiqun) seized upon the confusion to sow doubt about the Prophet’s consistency.

In this heated environment, religious identity became aggressively tribal and directional. The Jewish communities oriented themselves West (from Babylon/Medina toward Jerusalem), while Christian communities oriented themselves East.4 Religion was rapidly devolving into a dispute over compass bearings—a “physics of prayer” rather than a “metaphysics of piety”.1 It is against this backdrop of sectarian bickering and ritual obsessiveness that Ayat al-Birr descended as a “Divine Corrective,” shattering the developing orthodoxy of form over substance.1

1.2 The Deconstruction of Ritualism

The verse opens with a negation so sweeping that it remains unique in religious scripture: “It is not righteousness that you turn your faces toward the East or the West”.4 With this single declarative sentence, the Quran invalidates the primary source of religious contention in Medina. It does not dismiss the validity of the Qiblah (which it upholds elsewhere), but it dismisses the sufficiency of it. The verse asserts that “external motions mean little in isolation – what counts is the orientation of one’s heart and actions toward God’s guidance”.4

This opening serves as a “thunderclap against formalism”.1 It addresses the universal human tendency to reduce sanctity to mechanics. Classical scholars, including Al-Tabari, note that the verse was a direct response to those who believed that the mechanical performance of a rite constituted the totality of sanctity. By negating the “turning of faces” as the definition of Birr, the Quran challenges a superficial view of religion centered on ritual direction.4 It forces the believer to look away from the geographical horizon and inward toward the spiritual horizon. As one contemporary scholar notes, the verse shifts the focus from “mere ritual formalism to a holistic blend of sound faith, ethical commitment, social responsibility, and personal virtue”.4

1.3 Etymological Depth: Birr vs. Bahr

The Quranic choice of the term Birr to define this new holistic piety is linguistically profound. The root b-r-r implies “vastness, expanse, and stability.” It shares a lexical lineage with the word for land or earth (Barr), which stands in opposition to the sea (Bahr).1 The sea is fluid, volatile, changing, and uncertain; the land is firm, expansive, and reliable.

Therefore, to possess Birr is to possess “moral stability” and “firm ground.” Etymologically, righteousness in the Quran is not a fleeting emotional state or a sporadic act of kindness (which might be fluid like the sea); it is a stable, immovable state of character. Exegetes like Abul A’la Maududi describe Birr as an “umbrella word” for absolute good, representing the integration of a sincere heart, responsible action, and unwavering character.1 This linguistic nuance suggests that the “Architecture of Righteousness” is intended to be a fortress—a stable construction that protects the soul from the volatility of changing social norms or political pressures.

1.4 The Structural Integrity of the Verse

The analysis of Ayat al-Birr reveals that it is not a random list of virtues but a carefully engineered system. The commentary defines it as a “panoramic definition of true piety” that acts as a “measuring stick” for the essence of religion.4 The verse integrates four core dimensions into a unified phenomenology:

- Metaphysical Belief (Iman): The internal engine or “software” of the righteous personality.

- Economic Redistribution (Infaq): The external proof of faith through the sacrifice of cherished wealth.

- Ritual and Contractual Pillars (Ibadah and Wafa): The structural integrity of the community through prayer, Zakah, and the honoring of covenants.

- Moral Psychology and Resilience (Akhlaq and Sabr): The character traits required to sustain righteousness under pressure.1

This structure implies a necessary sequence. One cannot have sustainable charity (Infaq) without the motivation of faith (Iman). One cannot maintain the discipline of worship (Ibadah) without the psychological steel of patience (Sabr). The verse thus refuses to “compartmentalize the human experience,” asserting that there is no “religious life” separate from “social life”.1

Chapter 2: The Metaphysical Foundation (Iman)

2.1 The Internal Software of Righteousness

The “Architecture of Righteousness” begins deeply within the human psyche. The verse states: “But [true] righteousness is [in] one who believes in Allah, the Last Day, the angels, the Book, and the prophets…”.1 By placing creed before deed, the Quran establishes that “correct creed is the first pillar of righteousness”.4 Faith is the “internal software” that drives the hardware of the body; without it, ethical behavior may be socially beneficial but lacks the transcendent purpose required for durability.1

2.2 The Five Articles of Faith

The verse enumerates five specific articles of faith, each serving a distinct psychological and ethical function in the architecture of the self.

2.2.1 Belief in Allah: The Devaluation of Materialism

Belief in Allah is the recognition of a singular, absolute reality that devalues all other attachments. In the context of Ayat al-Birr, this belief is the antidote to the “love of wealth” mentioned later. If one believes that Allah is the sole possessor of value and the ultimate provider, the accumulation of material goods loses its existential urgency. This theological centering is the “wellspring of one’s horizontal conduct with fellow beings”.4

2.2.2 The Last Day: The Psychology of Accountability

The mention of the “Last Day” is pivotal for the ethical system of Islam. It acts as the “psychological driver of accountability”.1 In a secular ethical framework, the motivation for goodness may be social cohesion or personal satisfaction. However, these motivations can falter when the cost of virtue is high and the chance of detection is low. Belief in the Last Day transforms moral choices from short-term transactions into “long-term investments.” It instills a “moral responsibility through the realization of judgment”.4 The righteous person acts justly not because the law is watching, but because they believe the “Day of Accounting” is inevitable.

2.2.3 The Angels: The Unseen Administration

Belief in the angels connects the believer to the Ghayb (Unseen). It reinforces the idea that the universe is not a closed material system but a morally active cosmos. Angels are the recording scribes and the messengers of the Divine will; believing in them serves as a constant reminder of the unseen witnesses to human conduct.

2.2.4 The Book and The Prophets: Trans-historical Universalism

The verse uses generic and plural terms: “The Book” (Al-Kitab) and “The Prophets” (Al-Nabiyyin). This syntax is deliberate. It implies a belief in the “totality of revelation” and a “trans-historical community of truth”.1 By commanding belief in all prophets and all books, the Quran negates the sectarian selectivity that plagued the Jews and Christians of Medina. It fosters a “cosmopolitan theology” that recognizes the continuity of divine guidance. To be righteous, one cannot be a partisan sectarian; one must accept the universal fraternity of the prophets.

2.3 The Integration of Rights: God and Slave

A profound insight from contemporary scholarship on this verse is how it “seamlessly combines the rights of Allah and the rights of His slaves”.4 In many religious traditions, a dichotomy exists between the contemplative life (rights of God) and the active life (rights of humanity). Ayat al-Birr obliterates this duality.

The verse asserts that “devotion is not complete if one neglects human welfare, and social activism is not sufficient if one neglects the soul’s duties to its Lord”.4 Al-Tabari reinforces this by stating that Birr is the integration of the heart’s obedience to Allah with the body’s service to His creation. The “Rights of Allah” (worship) provide the spiritual voltage, while the “Rights of His Slaves” (charity) provide the conduit for that energy.

| The Articles of Faith | Psychological Function in “Ayat al-Birr” |

| Allah | Devalues material wealth; Centers the “Qiblah” of the heart. |

| The Last Day | Creates absolute accountability; Transforms sacrifice into investment. |

| The Angels | Awareness of the Unseen witnesses; Validates the metaphysical order. |

| The Book | Connects the believer to the divine law and guidance. |

| The Prophets | Establishes a trans-historical community; Negates sectarianism. |

Chapter 3: The Economic Theology (Infaq) and the Steep Path

3.1 The Friction of Sacrifice: “Despite Love For It”

Having established the internal software of belief, the verse immediately demands external proof: “and gives wealth, in spite of love for it” (wa ata al-mala ala hubbihi).1 This phrase contains a profound psychological insight into the “friction of giving.” The Quran does not merely command charity; it qualifies it. It acknowledges the natural human attachment to property—the “love” of wealth—and defines righteousness as the overcoming of this attachment.

It is not Birr to give away surplus, the unwanted, or the trivial. True righteousness requires a “sacrificial economy” where one gives that which is cherished. This resonates with Quran 3:92: “By no means shall you attain birr (righteousness) unless you spend from that which you love”.4 The act of giving thus becomes a “spiritual exercise” to break the shackles of greed and materialism.4 It functions as a purification of the soul, detaching the believer from the material world to prepare them for the spiritual one.

3.2 The Categories of Recipients: A Social Welfare Manifesto

The verse outlines a specific hierarchy of recipients, creating a concentric circle of responsibility that radiates outward from the individual. This list is “profoundly social,” indicating that righteousness resides in how one treats the disadvantaged 4:

- Kin (Dhawi al-Qurba): The immediate family and relatives. Charity begins at home, strengthening the biological and social nucleus of society. A Hadith notes that giving to relatives counts as both charity and Silah (nurturing relations).4

- Orphans (Al-Yatama): The most vulnerable, defined as children who have lost their fathers. In a patriarchal society like 7th-century Arabia, the orphan was economically defenseless. The Quran elevates their care to a primary marker of faith.

- The Needy (Al-Masakin): Those struggling with poverty who may not have the means to ask.

- The Wayfarer (Ibn al-Sabil): The stranded traveler. This category highlights the transience of human stability; anyone can become a wayfarer.

- Those Who Ask (Al-Sa’ilin): Beggars. The verse protects the dignity of the request, mandating a response to the one who humbles themselves to ask.

- In the Freeing of Slaves (Fi al-Riqab): A systemic intervention in human liberty.

3.3 Fi al-Riqab: The Theology of Emancipation

Among the categories of charity, Fi al-Riqab—”in the freeing of necks” (slaves/bondage)—stands out as a radical intervention. In the 7th-century context, where slavery was an economic bedrock of global empires, the Quran elevated the manumission of slaves to a primary act of worship. It transformed human freedom from a “political concession into a theological imperative”.1

This connects thematically to Surah Al-Balad (90), which defines the “Steep Path” (Al-Aqabah)—the difficult ascent to virtue—explicitly as Fakku Raqabah (the freeing of a slave).1 The “Architecture of Righteousness” is thus inherently liberationist. It posits that one cannot be truly righteous while being complicit in the bondage of others. The inclusion of this category signals that Ayat al-Birr is not just about alleviating poverty (feeding the poor) but about dismantling systemic oppression (freeing the slave).

3.4 Zakah vs. Sadaqah: Overflowing the Legal Minimum

The verse mentions “giving wealth” (ata al-mala) separately from “establishing prayer and giving Zakah” later in the text. Exegetes like Al-Qurtubi explain that the earlier mention refers to voluntary charity (Sadaqah), while Zakah is the fixed obligatory tax. This implies that true righteousness requires generosity that “overflows the legal minimums”.1 A legalist might pay their 2.5% Zakah and consider their duty done. The “Truthful” (Al-Sadiqun), however, recognizes that the needs of society—and the “love of wealth” in their own heart—require a giving that transcends statutory obligation.

Chapter 4: The Comparative Leadership of Conscience – Muhammad and Lincoln

4.1 The Liberators: A Shared Legacy Across Millennia

The inclusion of Fi al-Riqab (freeing of slaves) in Ayat al-Birr provides a powerful bridge to comparative history. When we survey the landscape of human leadership regarding liberty, two figures emerge with striking commonality despite being separated by twelve centuries and vast cultural distances: The Holy Prophet Muhammad and President Abraham Lincoln.

Research indicates that one quality is “immediately obvious”: they were “both liberators of slaves”.2

- Muhammad’s Paradigm: Through verses like Ayat al-Birr and Surah Al-Balad, Muhammad institutionalized the freeing of slaves as a primary mechanism of expiation (kaffara) and piety. He did not merely preach abolition; he created a “market demand” for freedom. Muslims were commanded to free slaves to atone for broken oaths, accidental manslaughter, and fasting violations. The Prophet himself freed 63 slaves, and his closest companion Abu Bakr spent his fortune buying and freeing tortured slaves like Bilal ibn Rabah.

- Lincoln’s Paradigm: Through the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment, Lincoln utilized the political and military apparatus of the state to break the legal chains of chattel slavery. Like Muhammad, Lincoln faced a society where slavery was deeply entrenched in the economic order. His evolution from a pragmatic politician to the “Great Emancipator” mirrors the Quranic gradualism—moving from restriction to total abolition.

4.2 The Sovereignty of Conscience

Beyond their role as liberators, the deepest resonance between Muhammad and Lincoln lies in their reliance on “human conscience for noble and compassionate living”.3 Both figures challenged the rigid orthodoxies of their times—Muhammad challenging the idolatrous status quo of Mecca, Lincoln challenging the constitutional interpretations that protected slavery—by appealing to a higher, internal law.

4.2.1 Lincoln’s “Political Religion” of Conscience

Abraham Lincoln, often enigmatic in his theological affiliations, articulated a creed that mirrors the essence of Ayat al-Birr. He famously stated:

“When I do good, I feel good. When I do bad, I feel bad. That’s my religion.”.2

This statement is profound in its simplicity. It rejects complex dogma in favor of the fitrah (innate nature)—the internal moral compass that intuitively recognizes right from wrong. It suggests that righteousness is verified by the tranquility of the soul, not merely by the applause of the crowd or the letter of the law.

4.2.2 The Prophetic Standard: “Seek the Guidance of Thy Soul”

This Lincolnian sentiment is almost a verbatim echo of a famous Hadith of Prophet Muhammad. When asked about righteousness (Birr), the Prophet replied:

“Seek the guidance of thy soul! Seek the guidance of thy soul! Seek the guidance of thy soul! The virtuous deed is one whereby thy soul feels restful and thy heart contented, and sinful act is one which rankles in thy soul and which contracts thy heart even though the other people endorse it as lawful.”.2

Here, the Prophet empowers the individual conscience against the potential corruption of external religious authority. Just as Ayat al-Birr dismisses the “East and West” of external ritualism, this Hadith dismisses the external validation of “other people” (or corrupt legal scholars who might issue permissive fatwas). The ultimate arbiter of Birr is the internal state of peace. If an action “rankles in the soul,” it cannot be righteous, regardless of its legal veneer.

4.3 Pluralism and the “Race to Good”

The connection extends to their vision of a pluralistic humanity. The Quranic verse 2:148, “wherever you are, Allah will gather you all,” and the command to “race to do good” (fastabiqu al-khayrat), anticipates a pluralistic ethos where diversity is not a cause for conflict but a competition in benevolence.6

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, with its lack of malice and charity for all, reflects this same spirit. Both leaders understood that the ultimate judgment belongs to the Divine. The “unlikely connection” between these figures reinforces the universality of the “Architecture of Righteousness.” Whether articulated in 7th-century Arabic revelation or 19th-century American political rhetoric, the core principles remain constant: the liberation of the oppressed and the sovereignty of the moral conscience are the truest measures of piety.

| Comparative Trait | Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) | President Abraham Lincoln |

| Primary Achievement | Transformation of Arabia; Establishment of Monotheism. | Preservation of the Union; Abolition of Slavery. |

| Relationship to Slavery | Institutionalized manumission as worship (Fi al-Riqab). | Institutionalized emancipation as law (13th Amendment). |

| Definition of Religion | “The virtuous deed is one whereby thy soul feels restful.” | “When I do good, I feel good… That’s my religion.” |

| Approach to Ritual | Prioritized Birr (Righteousness) over Qiblah direction (2:177). | Prioritized Union and Liberty over strict Constitutional formalism. |

| Legacy | The “Seal of the Prophets”; A Mercy to the Worlds. | The “Great Emancipator”; Savior of the Republic. |

Chapter 5: The Structural Pillars: Ritual and Contract

5.1 The Place of Ritual in a Post-Formalist Verse

After establishing faith and charity, Ayat al-Birr returns to ritual: “and establishes prayer and gives zakah”.1 A superficial reading might ask: “Did the verse not just say facing East or West is not righteousness?”

The nuance lies in the distinction between ritual and ritualism. The verse dismisses ritualism (the obsession with the form as an end in itself) but reinstates ritual (prayer and Zakah) as the “structural integrity of the community”.1

- Prayer (Salah): It is the daily recalibration of the “internal Qibla.” It serves as the temporal framework that organizes the believer’s life around the Divine. It acts as the “load-bearing wall” of the spiritual house.

- Zakah: As discussed, while Infaq is the overflow of generosity, Zakah is the systematic, obligatory redistribution of wealth. It ensures the basic economic floor of society is maintained, preventing the gross accumulation of wealth that leads to social collapse.

The “Architecture” thus requires pillars. Faith (Iman) is the foundation; Charity (Infaq) is the open door; but Prayer and Zakah are the structural framework. Without them, the structure collapses into vague spirituality without discipline.

5.2 The Sanctity of the Contract: “When They Promise”

The verse proceeds to a critical dimension of social ethics: “[those who] fulfill their promise when they promise” (wal-mufuna bi-ahdihim idha ahadu).1

In the pre-Islamic Arab context, and indeed in modern commerce, the contract is often viewed through the lens of utility—honored when convenient, breached when profitable. Ayat al-Birr elevates the fulfillment of covenants to a divine commandment.

This clause “elevates commercial and political contracts” to the level of worship.1 It suggests that a “righteous” person who cheats in business or breaks a treaty is a contradiction in terms. This has profound implications for the stability of the Islamic state and civil society. Trust (Amanah) is the currency of social interaction; without it, the “horizontal” relationship between humans disintegrates. The Quranic linkage here is stark: one cannot claim to believe in the “Last Day” and yet break a promise in the “present day.” The integrity of the word is a reflection of the integrity of the faith.

Chapter 6: The Psychology of Resilience (Sabr)

6.1 The Grammar of Specification: Al-Ikhtisas

The final pillar of the Architecture of Righteousness is Sabr (Patience/Fortitude). Here, the Quran employs a subtle but powerful grammatical shift known as Iltifat (turning). The text switches from the nominative case to the accusative case for the word “The Patient” (Al-Sabirin). Grammarians like Nouman Ali Khan identify this as Al-Ikhtisas (Specification), effectively meaning: “And [I especially praise] the Patient”.1

This “Grammatical Highlighter” signals that patience is not just another virtue on the list; it is the “foundational quality required for all preceding acts”.1 It is the “glue that holds all other virtues together”.4 One cannot maintain faith during doubt, give wealth during scarcity, or fulfill covenants during temptation without the psychological steel of Sabr.

6.2 The Three Theaters of Patience

The verse specifies three distinct scenarios for patience, covering the spectrum of human suffering:

- Al-Ba’sa’ (Poverty/Hardship): Economic adversity. Patience here is dignity—the refusal to compromise ethics for survival. It is the patience of the poor who refuse to steal.

- Al-Darra’ (Illness/Injury): Physical and personal suffering. Patience here is acceptance of the Divine decree without despair. It is the patience of Job (Ayyub).

- Hina al-Ba’s (Times of Conflict/Panic): The “heat of battle” or societal crisis. Patience here is courage and steadfastness.1 It is the patience of the soldier standing their ground, or the leader maintaining calm in a crisis.

6.3 The Litmus Test of Truth

The verse concludes with a definitive verdict: “Those are the ones who have been true, and it is those who are the righteous” (Ula’ika alladhina sadaqu wa ula’ika hum al-muttaqun).

The use of Sadaqu (they have been truthful) is telling. It implies that without these qualities—specifically the resilience of Sabr—faith is merely a claim. The “Patient ones” are those who have “proved themselves true”.4 The Architecture of Righteousness is thus a mechanism of verification. It separates the “Hypocrites” (Munafiqun), who may pray outwardly but flee in crisis or hoard in greed, from the “Truthful” (Sadiqun), whose interior faith is ratified by their external sacrifice and resilience.

Chapter 7: Thematic Intertextuality and Synthesis

7.1 The Quranic Ecosystem of Righteousness

The insights of Ayat al-Birr do not exist in a vacuum. A “definitive exegetical analysis” reveals deep “Thematic Intertextuality” with other chapters, confirming that the Quranic message is a cohesive whole.1

7.1.1 Surah Al-Ma’un: The Hollow Prayer

Surah Al-Ma’un (107) serves as the shadow to Ayat al-Birr’s light. It asks: “Have you seen him who denies the Recompense?” It then identifies this denier not as an atheist, but as “he who repulses the orphan and encourages not the feeding of the poor.” It warns: “So woe to those who pray, [but] who are heedless of their prayer”.1

This reinforces 2:177’s central thesis: prayer without social ethics is hollow. The one who prays but ignores the orphan has “denied the faith” in spirit, even if they affirm it in word.

7.1.2 Surah Al-Balad: The Steep Path

Surah Al-Balad (90) provides the operational manual for the “Righteous.” It describes the human condition as Kabad (struggle) and asks: “And what will explain to you what the Steep Path (Al-Aqabah) is?” The answer mirrors 2:177 perfectly: “It is the freeing of a slave (Fakku Raqabah), or feeding on a day of severe hunger”.1

Surah Al-Balad teaches that righteousness is an uphill climb against the lower self (nafs). It confirms that the “freeing of necks” (Riqab) is the summit of this climb.

7.1.3 Surah Al-Lail and Al-Fajr: The Economic Trajectory

Surah Al-Lail (92) contrasts the one who gives (A’ta) and fears God with the miser, showing that our economic choices dictate our spiritual trajectory. Surah Al-Fajr (89) diagnoses our “inherent greed” (loving wealth with immense love) as the root of social decay, which only the “radical charity” of 2:177 can cure.1

7.2 Conclusion: The Architecture of the Core

In the final analysis, Ayat al-Birr stands as the “Architecture of the Core” for the Muslim personality. It dismantles the superficial scaffolding of ritualism—facing East or West as an end in itself—and replaces it with a robust structure built on the bedrock of monotheistic conviction (Iman), sustained by the circulation of wealth (Infaq), framed by the discipline of worship (Ibadah), and fortified by the steel of character (Sabr).

The comparative analysis with Abraham Lincoln amplifies the verse’s universal resonance. It demonstrates that the principles of Ayat al-Birr—liberation of the enslaved, the primacy of conscience, and the integrity of the soul—are the shared heritage of the “Truthful” across history. Whether in the deserts of 7th-century Arabia or the war-torn landscape of 19th-century America, the definition of righteousness remains constant.

As the verse asserts, those who embody this architecture are “the ones who are true.” They have moved beyond the geography of the “East and West” to inhabit the “firm ground” of Birr, establishing a legacy that—like the actions of Muhammad and Lincoln—transcends time and orientation to touch the eternal.

Leave a comment