Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Audio summary:

Abstract

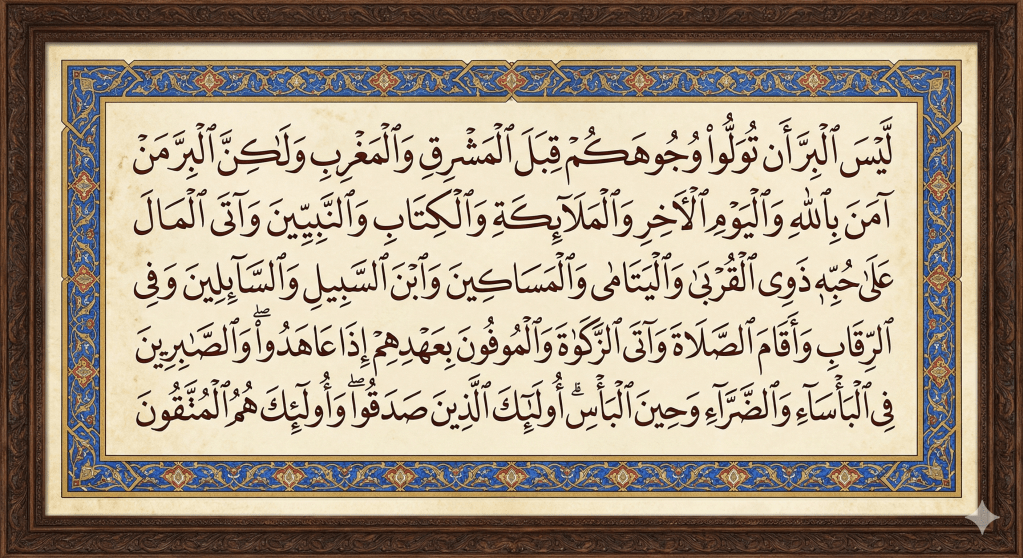

This extensive research report presents a comprehensive exegetical analysis of Surah Al-Baqarah, Verse 177 (Ayat al-Birr), positing it as the central dogmatic and ethical manifesto of the Quranic discourse. While often categorized merely as a transitionary verse following the change of the Qiblah (direction of prayer), this report argues that Verse 177 serves as the foundational “constitution of the Muslim soul,” integrating metaphysical belief (Iman), economic redistribution (Infaq), ritual adherence (Ibadah), and moral psychology (Akhlaq) into a unified phenomenology of “The Truthful” (Al-Sadiqun). The analysis synthesizes classical exegesis—primarily drawing from Ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Ibn Kathir, and Al-Qurtubi—with the socio-political and spiritual insights of contemporary commentators such as Sayyid Qutb, Abul A’la Maududi, and the editors of The Study Quran (Seyyed Hossein Nasr et al.).

Critically, this report establishes a rigorous intertextual dialogue between Verse 2:177 and four other pivotal Quranic chapters: Surah Al-Ma’un (107), Surah Al-Balad (90), Surah Al-Lail (92), and Surah Al-Fajr (89). By treating these chapters as expanded commentaries on the specific clauses of 2:177, the report illuminates the operational mechanisms of righteousness—defining it not as static ritualism but as the “Steep Path” (Al-Aqabah) of liberating human consciousness from the gravity of greed (Hubban Jamma) and social apathy. The study concludes that 2:177 is the theological antidote to the social pathologies diagnosed in the Meccan surahs, offering a timeless framework for the “Integrated Self” that harmonizes the vertical relationship with the Divine and the horizontal relationship with humanity.

Chapter 1: The Historical and Theological Crucible

1.1 The Context of Revelation: The Crisis of Orientation

To understand the magnitude of Verse 2:177, one must first reconstruct the volatile socio-religious atmosphere of Medina in the second year of the Hijrah (migration). The nascent Muslim community was undergoing a profound transition from a persecuted minority in Mecca to a sovereign socio-political entity in Medina. Central to this transition was the establishment of a distinct religious identity, symbolized most potently by the Qiblah—the direction of ritual prayer.

For approximately sixteen to seventeen months after arriving in Medina, the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and his followers prayed facing Jerusalem (Bayt al-Maqdis). This orientation served multiple divine purposes: it signaled the continuity of the Islamic message with the Abrahamic lineage of Isaac and Jacob, and it acted as a conciliatory bridge towards the Jewish tribes of Medina (Banu Qaynuqa, Banu Nadir, and Banu Qurayzah). However, this period was also a test of the believers’ resilience and obedience.

The command to shift the Qiblah from Jerusalem to the Kaaba in Mecca (Quran 2:144) precipitated a crisis. This was not merely a change of cardinal direction; it was a geopolitical and theological rupture.

- The Jewish Tribes questioned the validity of a Prophet who would alter the time-honored orientation of the Patriarchs, asking, “What has turned them away from the Qiblah they used to face?” (2:142).

- The Hypocrites (Munafiqun) seized upon this as evidence of Muhammad’s inconsistency or political opportunism.

- The Believers faced a crisis of formalism: If the direction can change, what is the permanent reality of faith?

It is into this chaotic discourse that Verse 177 descends as a “Divine Corrective.” As Ibn Kathir elucidates, the verse was revealed to dismantle the obsession with the “forms” of religion. He notes that the change of Qiblah was a trial to distinguish those who followed the Messenger from those who turned on their heels. Verse 177 elevates the discussion from the physics of prayer to the metaphysics of piety, declaring that the direction itself is not the objective; obedience to the Commander is the objective.

1.2 Linguistic Deconstruction: The Meaning of Al-Birr

The verse opens with a powerful negation: “Righteousness is not that you turn your faces toward the east or the west” (Laysa al-birra an tuwallu wujuhakum…). To appreciate the weight of this statement, we must analyze the term Al-Birr.

Etymology and Semantics:

- Root: The Arabic root b-r-r conveys meanings of vastness, expanse, and stability. It is shared with the word Barr (land/earth) as opposed to Bahr (sea). This implies that Birr is a firm ground upon which one stands, a comprehensive landscape of goodness that is not fluid or unstable.

- Classical Usage: In pre-Islamic poetry and usage, Birr referred to the extensive fulfillment of rights and ample kindness. It is often paired with Taqwa (God-consciousness) but is distinct; if Taqwa is the internal defensive mechanism against sin, Birr is the external offensive mechanism of doing good.

- The Umbrella Concept: Abul A’la Maududi describes Birr as an “umbrella word” used for what is good in the absolute sense. It combines acts of righteousness, obedience, and moral rectitude into a single term. It is the comprehensive attribute of the perfect believer.

Al-Tabari reinforces this holistic definition, arguing that Birr is not a single act but the integration of a sincere heart, responsible action, and unwavering character. By negating the turning of faces East or West as the definition of Birr, the Quran is not dismissing ritual (as it later commands prayer in the same verse), but it is dismissing ritualism—the belief that the mechanical performance of a rite constitutes the totality of sanctity.

1.3 The Polemic Against Formalism

Sayyid Qutb, in his seminal commentary In the Shade of the Quran, views this opening negation as a decisive break from the “ossification” of religion. He argues that human nature has a persistent tendency to cling to symbols and forms because they are tangible and easy to perform. It is easier to face East or West than it is to give away cherished wealth or endure torture with patience.

- The Jewish Context: The Jews faced West (towards the Holy of Holies).

- The Christian Context: The Christians faced East (towards the rising sun/Second Coming). By mentioning both “East and West,” the Quran addresses both major religious communities of the time, as well as the Muslims who had faced both directions. Nouman Ali Khan adds that this negation serves to humble the believer; it reminds them that the Kaaba is just stone and mortar, and Jerusalem is just a location; their sanctity is derived solely from Allah’s command. To worship the direction is idolatry; to worship the Commander is Birr.

Table 1.1: The Dichotomy of Directions vs. Essence

| Dimension | “Turning Faces” (Formalism) | Al-Birr (Essence) |

| Focus | External Orientation (East/West) | Internal Orientation (Iman/Taqwa) |

| Nature | Mechanical, Ritualistic | Transformative, Ethical |

| Stability | Subject to Abrogation (Change of Qiblah) | Immutable (Universal Values) |

| Human Cost | Low (Physical movement) | High (Sacrifice of wealth/self) |

| Goal | Identity/Tribalism | Submission/Truthfulness |

Chapter 2: The Metaphysics of Truth (Iman)

Following the negation of mere formalism, the verse establishes the foundational “software” of the righteous personality: the Creed (Aqidah). “But [true] righteousness is [in] one who believes in Allah, the Last Day, the angels, the Book, and the prophets…” (2:177).

2.1 The Architectonics of Belief

The listing of these five articles of faith is not arbitrary. It represents a coherent theological worldview that serves as the engine for the ethical actions that follow.

1. Belief in Allah (Allah): The primary axiom. As The Study Quran (Seyyed Hossein Nasr) notes, this is not merely an intellectual assent to a “Creator” (which even the pagan Meccans held) but a comprehensive Tawhid (Oneness) that necessitates absolute submission. It is the recognition of God as the sole possessor of value, which subsequently devalues material wealth (addressed in the next clause).

2. The Last Day (Al-Yawm Al-Akhir): Placed immediately after belief in Allah, the Last Day introduces the concept of Ultimate Accountability. This is the psychological driver of Birr.

- Connection to Surah Al-Ma’un (107): As we shall explore in the intertextual analysis, the denial of the “Recompense” (Al-Din) is the root cause of social apathy. The one who does not believe in a future reckoning has no rational incentive to sacrifice present pleasure (wealth) for the sake of others. Belief in the Last Day is the “long-term investment” strategy of the Righteous.

3. The Angels (Al-Mala’ikah): Why are angels mentioned here? Al-Tabari suggests this emphasizes belief in the unseen mechanism of revelation and record-keeping. Angels are the conduits of the Divine Command (Amr) and the constant witnesses over human action. Belief in them creates a sense of constant surveillance and companionship with the celestial realm, elevating the believer’s conduct even in private.

4. The Book (Al-Kitab): The use of the singular/generic Al-Kitab (The Book) rather than “The Quran” is significant. It implies a belief in the phenomenon of Revelation itself—accepting the Torah, the Gospel, the Psalms, and the Quran as part of a single, continuous divine curriculum. This negates the sectarianism of the Jews and Christians who rejected each other’s scriptures. The Righteous person accepts the totality of God’s speech.

5. The Prophets (Al-Nabiyyin): Similarly, the plural “Prophets” necessitates a universal acceptance of all divine messengers. This creates a “trans-historical” community of truth. Ibn Kathir points out that this specific formulation was a rebuttal to the People of the Book, who were selective in their belief (e.g., Jews rejecting Jesus and Muhammad; Christians rejecting Muhammad). Birr requires an unprejudiced acceptance of the truth, regardless of the messenger.

2.2 The Mystical Dimension: The “Inner Qibla”

While classical exegetes focus on the dogmatic aspects, the Sufi commentaries offer an esoteric perspective on this section. Tafsir Al-Kashani (attributed to Ibn Arabi or Abd al-Razzaq al-Kashani) interprets the “East and West” as symbols of the spiritual and physical worlds.

- East: The world of Spirits (Alam al-Arwah)—the place of rising light.

- West: The world of Bodies (Alam al-Ajsam)—the place of setting/darkness. Kashani argues that true Birr is not turning solely to the world of spirits (asceticism) nor solely to the world of bodies (materialism), but establishing a “Unitary Vision” that sees God (Allah) in all things. The “Inner Qibla” is the heart’s orientation towards the Divine Essence, independent of spatial direction.

Chapter 3: The Economics of Piety (Infaq) – Part 1: The Psychology of Giving

Immediately following the internal reality of faith, the verse pivots to its external proof: the giving of wealth. This sequencing is deliberate—faith (Iman) that does not manifest in expenditure (Infaq) is, according to the Quranic logic, nonexistent.

3.1 The Meaning of Ala Hubbihi: The Friction of Sacrifice

The phrase wa ata al-mala ala hubbihi (“and gives wealth, in spite of love for it”) contains a profound psychological insight. The pronoun hu (it/him) in hubbihi presents a famous interpretive duality:

- Love for Allah (The Object of Worship): This interpretation, favored by some early exegetes, suggests the motivation is “for the love of God.” While theologically true, linguistic evidence suggests this is secondary in this specific context.

- Love for Wealth (The Object of Desire): This is the preferred interpretation of Ibn Kathir, Al-Tabari, and Maududi. The grammar links the pronoun back to the nearest noun (Al-Mal).

- Implication: This interpretation introduces the concept of friction. It is not “Birr” to give away what is surplus, unwanted, or easy to part with. True Righteousness is found in the struggle against one’s own attachment. It implies giving the “good stuff”—the wealth one desires, the assets one cherishes.

Nouman Ali Khan elaborates that this clause attacks the core of human insecurity. We love wealth because it represents security and power. Giving it away “despite love” means voluntarily dismantling one’s own false sense of security, trusting instead in the security of the “Last Day” mentioned in the previous breath.

3.2 Intertextual Analysis: The Diagnosis of Greed in Surah Al-Fajr (89)

To fully understand the necessity of the phrase Ala Hubbihi, we must examine Surah Al-Fajr (89:17-22), which serves as a diagnostic report on the human condition regarding wealth.

The Diagnosis (Surah Al-Fajr):

- “And you devour inheritance with devouring greed (aklan lamman).” (89:19)

- “And you love wealth with abounding/immense love (hubban jamma).” (89:20)

The Cure (Surah Al-Baqarah 2:177):

- Verse 2:177 acknowledges the diagnosis: Humans have Hubban Jamma (immense love) for wealth.

- The prescription is Ata al-mala ala hubbihi. The “Righteous” are not those who lack the instinctual love for wealth (which is natural), but those who override that instinct through the power of Iman.

Synthesis: The intertextuality reveals that Birr is a victory over biology. The natural biological drive is to hoard (Hubban Jamma); the spiritual imperative is to distribute (Infaq). The tension between Hubban Jamma (89:20) and Ala Hubbihi (2:177) is the battlefield where righteousness is forged.

3.3 The Mechanism of Giving: Surah Al-Lail (92)

Surah Al-Lail provides the operational mechanism for this transaction. It categorizes humanity into two archetypes based on this very struggle.

Table 3.1: The Archetypes of Giving in Surah Al-Lail vs. 2:177

| Archetype | Surah Al-Lail Description (92:5-11) | Correlation to 2:177 | Consequence |

| The Giver | “He who gives (A’ta) and fears (Ittaqa) and believes in the Best (Saddaqa bi-Husna).” | Matches: Ata al-mal (Gives), Muttaqun (Righteous), Amana (Believes). | Facilitated towards Ease (Yusra). |

| The Miser | “He who withholds (Bakhila) and considers himself self-sufficient (Istaghna) and denies the Best.” | The antithesis of 2:177. Denies the “Last Day.” | Facilitated towards Difficulty (Usra). |

Insight: Surah Al-Lail clarifies that the ability to “give despite love” (2:177) is contingent on “believing in the Best” (92:6)—i.e., the compensation of the Afterlife. The miser withholds because he “denies the Best” (92:9). Thus, the economic behavior is merely a symptom of the theological state.

Chapter 4: The Economics of Piety (Infaq) – Part 2: The Recipients

After establishing the psychology of giving, Verse 177 delineates a precise social hierarchy of recipients. This list is not random; it moves from the immediate circle of responsibility to the systemic liberation of the oppressed.

4.1 The Circle of Kinship (Dhawi al-Qurba)

- Definition: Relatives and extended family.

- Commentary: Al-Qurtubi emphasizes that charity to non-relatives while one’s own family starves is spiritually deficient. This prioritizes the stabilization of the family unit, the basic atom of society. If every family took care of its own vulnerable members, the state’s welfare burden would be drastically reduced.

4.2 The Vulnerable: Orphans and The Needy

- Orphans (Al-Yatama): Those who have lost their fathers (economic protectors) before puberty.

- The Needy (Al-Masakin): The root s-k-n implies stillness. These are people whose poverty has immobilized them; they cannot move to find work or are humbled by their lack.

Intertextual Embellishment: Surah Al-Ma’un (107) Surah Al-Ma’un provides a terrifying counter-narrative to 2:177. It defines the Mukadhdhib (Denier of Faith) not by their theology, but by their sociology:

- “That is the one who repulses the orphan (Yadu’u al-yatim).” (107:2)

- “And does not urge the feeding of the poor (Miskin).” (107:3) While 2:177 commands giving to the orphan, 107 condemns repulsing them. While 2:177 commands feeding the Miskin, 107 condemns failing to even encourage others to feed them. This implies that Birr is an active engagement with the vulnerable; anything less is a slide towards disbelief.

4.3 The Transient and The Voiceless

- The Wayfarer (Ibn al-Sabil): Literally “Son of the Road.” This refers to travelers cut off from their resources. Sayyid Qutb notes this establishes a universal brotherhood—a Muslim is at home anywhere in the Muslim lands, supported by the community. It breaks down tribal xenophobia.

- Those Who Ask (Al-Sa’ilin): Beggars. While Islam discourages begging, it obligates the community to respond to the beggar with dignity, acknowledging their right to asking when in dire need.

4.4 Systemic Liberation: Fi Al-Riqab (In the Necks)

- Definition: Slaves, captives, and those in bondage.

- The Steep Path of Surah Al-Balad (90): This category connects directly to Surah Al-Balad, which frames life as a struggle to climb a “Steep Path” (Al-Aqabah).

- The Question: “And what can make you know what is the Steep Path?” (90:12).

- The Answer: “It is the freeing of a slave (Fakku Raqabah).” (90:13). The Quran identifies the liberation of human beings as the summit of spiritual exertion. The term Fi al-Riqab (“In the necks”) in 2:177 implies that the charity is placed in the cause of their freedom—i.e., purchasing their manumission.

Sayyid Qutb’s Social Justice Theory: Qutb argues that this verse is evidence of Islam’s “Organic Method” of abolition. Rather than a sudden decree that might have led to social chaos or economic collapse (and subsequent re-enslavement), Islam integrated emancipation into the very definition of piety. By making the freeing of slaves a prerequisite for Righteousness (and a usage of Zakah funds), Islam turned the economic loss of manumission into a spiritual gain, ensuring a committed, pious drive towards a slave-free society. This transforms human freedom from a political concession into a theological imperative.

Chapter 5: The Ritual and The Contractual

Having established the internal belief and the external expenditure, the verse now addresses the ritual and legal pillars of the community.

5.1 The Pillars: Prayer and Zakah

“…and establishes prayer and gives zakah…”

The Distinction of Zakah: A critical legal question arises: Why is Zakah mentioned here if “giving wealth” was already detailed in the previous section?

- Al-Jassas and Al-Qurtubi explain that the earlier “giving” refers to Sadaqah (voluntary charity) or Haqq al-Mal (rights in wealth beyond Zakah, such as emergency aid). Zakah, conversely, is the fixed, obligatory state tax.

- Insight: This implies that Birr is not satisfied merely by paying one’s taxes (Zakah). True Righteousness requires a generosity that overflows the legal minimums. One cannot watch a neighbor starve and say, “I have paid my Zakah, I am absolved.” The duty of “giving wealth despite love” remains active alongside Zakah.

Establishment of Prayer (Iqamat as-Salah): The verse uses the term “Establish” (Aqama), implying structural integrity and constancy.

- Contrast with Surah Al-Ma’un: Surah 107 condemns those who are “heedless of their prayer” (Sahun)—those who pray to be seen (Yura’un). 2:177 defines the Sadiqun (Truthful) as those who establish prayer with sincerity, distinguishing them from the hypocrites of Al-Ma’un.

5.2 The Social Contract: Fulfilling Covenants

“…and those who fulfill their promise when they promise…”

Al-Tabari links this clause to the definition of a hypocrite (Munafiq), who “breaks promises when he makes them.” In the Medinan context, this had profound political implications.

- Treaties: It referred to the treaties with the Jewish tribes and the pagan Arab tribes.

- Allegiance: It referred to the Bay’ah given to the Prophet.

- Business: It referred to commercial contracts. Maududi notes that a society where contracts are not honored is a society in chaos. Birr requires that a Muslim’s word be immutable. This elevates the “promise” to a divine commandment, essential for the stability of the nascent Islamic state.

Chapter 6: The Psychology of Resilience (Sabr)

The verse concludes its list of attributes with a focus on the psychological state required to sustain all the above virtues.

6.1 The Grammatical Shift (Al-Ikhtisas)

Nouman Ali Khan and classical grammarians note a stunning shift in syntax here. The previous attributes were in the nominative case (Al-Mufuna – Those who fulfill). However, “The Patient” is in the accusative case (Al-Sabirin), even though it is part of the same list.

- Function: This is a rhetorical device known as Al-Qat’ (The Cut) or Al-Ikhtisas (Specification). It implies an unstated verb: “[And I especially praise] the Patient.”

- Significance: This grammatical highlighter signals that Sabr (patience/perseverance) is the foundational quality required for all the preceding acts. You cannot give wealth without patience against greed. You cannot pray without patience against laziness. You cannot keep promises without patience against expediency.

6.2 The Three Theaters of Patience

The verse specifies three contexts for patience, covering the totality of human suffering:

- In Poverty (Al-Ba’sa’): Economic hardship. Patience here is dignity—not begging, not stealing, not losing faith despite destitution.

- In Hardship/Illness (Al-Darra’): Physical suffering and personal tragedy. Patience here is accepting the Divine Decree without complaint.

- In the Heat of Battle (Heen al-Ba’s): Military conflict. Patience here is courage—standing firm when the enemy advances.

Al-Qurtubi notes that Al-Ba’sa (poverty) is mentioned to link back to the charity section—even when poor, the righteous maintain their integrity. Heen al-Ba’s (Battle) prepares the community for the inevitable defense of Medina (Badr, Uhud).

Chapter 7: Esoteric and Contemporary Perspectives

7.1 The Sufi Perspective: The Inner Qibla

Beyond the legal and social interpretations, Sufi commentators like Ibn Ajiba and Al-Qushayri (referenced in the Lata’if al-Isharat) view Verse 177 as a map of the spiritual journey.

- The Negation: Turning away from the “East” of the ego and the “West” of the material world.

- The Belief: The station of Ma’rifa (Gnosis)—witnessing the Divine in all levels of existence (Angels/Books).

- Giving Wealth: The station of Zuhd (Asceticism)—detachment from the world.

- Patience: The station of Rida (Contentment) with God’s decree. For the mystic, Birr is the annihilation of the self in the will of the Beloved.

7.2 The Modernist/Reformist Perspective

Sayyid Qutb and Maududi utilize this verse to argue for Islam as a complete civilization. They reject the secularization of religion that reduces Islam to “mosque attendance.”

- Maududi argues that 2:177 defines the “Party of God” (Hizbullah). It is a manifesto for the leaders of the Islamic movement. Only those who embody these traits are fit to lead the Ummah.

- The Study Quran highlights the universalist potential of the verse. By deemphasizing “East and West,” the verse opens a door for interfaith dialogue based on shared ethical values (charity, truthfulness, belief in God), suggesting that Birr is a perennial wisdom accessible to the sincere seekers of all traditions, provided they align with the Truth.

Thematic Epilogue: The Integrated Self

The analysis of Ayat al-Birr, illuminated by the diverse voices of the tradition and the supporting Quranic chapters, reveals a singular truth: The Quran refuses to compartmentalize the human experience.

There is no “religious life” separate from “social life.” There is no “ritual” separate from “ethics.”

- Surah Al-Ma’un warns us that prayer without social ethics is hollow.

- Surah Al-Balad teaches us that righteousness is an uphill climb against the self.

- Surah Al-Lail shows us that our economic choices dictate our spiritual trajectory.

- Surah Al-Fajr diagnoses our inherent greed, which only the radical charity of 2:177 can cure.

Verse 2:177 concludes with the ultimate title: “Those are the ones who have been True (Sadaqu), and it is those who are the Righteous (Al-Muttaqun).” Sidq (Truthfulness) is the alignment of the internal and the external. The Sadiq is not a hypocrite who prays but cheats; nor a secularist who gives charity but denies the Divine. The Sadiq is the Integrated Self—one who faces the Qiblah with their body, faces the Creator with their soul, and embraces humanity with their wealth and mercy. This is the definition of Birr.

Data Appendix: Comparative Analysis of Recipient Categories

| Recipient Category (2:177) | Societal Role/Vulnerability | Corresponding Systemic Solution | Intertextual Reference |

| Kin (Dhawi al-Qurba) | Family stabilization; preventing atomization. | Inheritance Laws (Mirth); Silat ar-Rahim. | Al-Fajr 89:19 (Critique of devouring inheritance). |

| Orphans (Al-Yatama) | Most vulnerable; lack of economic guardian. | Guardianship (Kafala); Preservation of orphan wealth. | Al-Ma’un 107:2 (Condemnation of repulsing the orphan). |

| The Needy (Al-Masakin) | The “stuck” poor; hidden poverty. | Social Welfare; Zakah. | Al-Balad 90:14-16 (Feeding on a day of hunger). |

| Wayfarer (Ibn al-Sabil) | The transient stranger; disconnected from tribe. | Hospitality rights; universal brotherhood. | – |

| Beggars (Al-Sa’ilin) | Those in desperate, visible need. | Redistribution; prohibition of rebuking beggars. | Al-Duha 93:10 (“And as for the petitioner, do not repel him”). |

| Slaves (Fi al-Riqab) | The unfree; absolute disenfranchisement. | Abolition; Zakah for manumission. | Al-Balad 90:13 (The Steep Path is freeing a slave). |

Leave a comment