Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

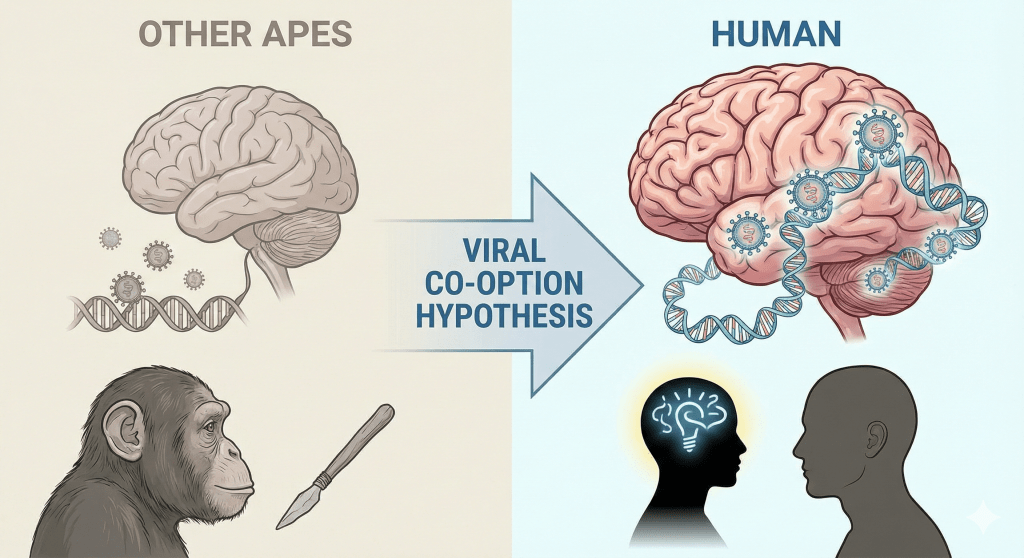

Viruses, particularly ancient retroviruses, have paradoxically shaped the very features that make us human. In recent decades, scientists have discovered that remnants of retroviral DNA within our genome have been “domesticated” by our cells to perform critical functions. Approximately 8% of the human genome is composed of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) – genetic traces of old viral infectionsnature.com. Far from being inert “junk” DNA, these viral legacies have been co-opted as regulators of gene expression and even as active proteins essential for development. In the brain, finely tuned activity of HERVs and other mobile elements (like LINE-1 transposons) is now recognized as a key factor differentiating human neural development and cognitionscientificarchives.com. One astonishing example is Arc, a gene crucial for memory and learning, which turns out to be a repurposed retroviral element that behaves like a virus within our neuronsbigthink.combigthink.com. Such findings shed light on the biological underpinnings of our capacity for complex thought and language, suggesting that viral “invasions” were not mere accidents but instrumental in crafting the neural architecture for speech. This article explores how ancient viral sequences contributed to the emergence of the human brain’s unparalleled complexity and our unique gift of language. In doing so, it frames these scientific insights in the context of guided (theistic) evolution, proposing that the remarkable repurposing of viral genetics hints at a purposeful design woven into the evolutionary process.

Introduction

Evolution is often portrayed as a blind, undirected process driven solely by random mutations and natural selection. Yet, recent discoveries in genomics and neuroscience are prompting a re-examination of that view. The human genome is not a pristine blueprint, but rather a mosaic built from myriad pieces – including the genetic footprints of viruses. Instead of evolving in isolation, our ancestors’ genomes incorporated DNA from viral infections, some of which became permanent fixtures passed down through generations. Surprisingly, these once-invasive sequences have been retooled by our cells over millennia to serve vital roles in our biologyreasons.orgpdb101.rcsb.org. This realization “is changing how we view the evolutionary process” by showing that organisms sometimes borrow genetic material from viruses, not just rely on random point mutationsbigthink.com.

Nowhere is this viral contribution more profound than in the brain. The human brain’s leap in complexity – enabling abstract thought, self-awareness, and language – may owe debts to these genetic gifts from viruses. Modern research reveals that retroviral elements helped drive the expansion and wiring of the brain, providing regulatory switches for genes and even novel proteins that enhance neural communicationscientificarchives.combigthink.com. Such intricately coordinated changes hint at an underlying direction to evolution. For a faith-based perspective, this invites reflection: could the integration of viral code into our genome be part of a divinely guided creative plan? Rather than viewing evolution and faith as opposing explanations, we find in the story of endogenous retroviruses a harmonious narrative – one in which God’s providence works through what science sees as chance, turning viral “intruders” into indispensable contributors to human development. In the sections that follow, we delve into the science of how retroviruses influenced the human brain and language, and discuss why these insights inspire an image of guided evolution over blind happenstance.

Viral DNA in Our Genome: Junk or Genius?

Early geneticists were startled to find that large portions of our DNA do not code for proteins and appear to come from strange origins. In fact, roughly 45–50% of the human genome is composed of transposable elements and other repetitive sequences, much of it stemming from ancient viral insertionsscientificarchives.com. Of particular interest are the human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), fragments of retrovirus genomes that integrated into the DNA of our germline (sperm or egg cells) long ago. These fragments – about 8% of our genome – are essentially molecular “fossils” of past infectionsnature.com. For decades, HERVs were dismissed as useless junk DNA, genomic flotsam that evolution carried along. This assumption was partly because HERVs sit in an “unfamiliar and unexpected context” (inside our chromosomes rather than inside virus particles)reasons.org. However, as biologists have probed these elements more deeply, a paradigm shift occurred. Many HERV sequences have been found to serve important functions, leading researchers to realize that “sometimes things that appear to be junk are there for a reason”reasons.org.

One dramatic example of viral DNA repurposed for our benefit is Syncytin, a protein crucial for placenta formation. Syncytin is encoded by an env gene derived from an endogenous retrovirus in the human genomenature.com. During mammalian evolution, a retrovirus infected an ancestor and left behind a gene that, eons later, became essential for pregnancy. Syncytin is expressed in the placenta where it causes cell fusion, helping form the layer that connects mother and fetusnature.com. In other words, without an ancient virus’s DNA donation, human childbirth as we know it might not be possible. This is a striking case of an initially parasitic sequence becoming a life-giving element – what was “meant for harm” transformed into good. Beyond the placenta, scientists have identified numerous instances where endogenous retroviral genes or their regulatory sequences are active contributors to normal physiologypdb101.rcsb.org. These include roles in immune modulation, cellular fusion, and developmental processesscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. Such findings erode the notion of HERVs as mere genomic clutter and instead highlight them as a wellspring of evolutionary innovation – raw material that natural selection (or, one might say, the Creator working through natural processes) could shape into new functions.

From a theistic evolution standpoint, the discovery of function in “junk” DNA carries profound meaning. It suggests that the Master Designer embedded resilience and adaptability into creation at a genetic level. What appeared to be wasted sequence was, in fact, a reservoir of potential, foreseen by God’s providence to be unmasked at the right times. As one observer from a design perspective noted, the emerging evidence of HERV function “justifies our position” that genomes reflect intentional planning, not random accidentreasons.org. Indeed, the repurposing of viral genes for critical uses – like nourishing a developing baby via the placenta – has been cited as an instance where a creative hand is discernible in evolution’s historypdb101.rcsb.org. Rather than disproving evolution, these viral contributions enrich it, painting a picture of a process that is fundamentally creative and purpose-driven.

Endogenous Retroviruses as Brain Architects

If viral genes can shape something as foundational as reproduction, could they also have molded the most distinctive human organ – the brain? Research in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo) says yes. The development of the human nervous system is an intricate symphony of gene regulation, cell migration, and synaptic formation. Scientists have found that ancient retroviral elements are active conductors in this symphony, especially during early embryonic stages and in neural progenitor cellsscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. HERV sequences often come with long terminal repeats (LTRs) that can act as gene promoters or enhancers. During brain development, some of these viral-derived promoters turn on or modulate the expression of nearby human genes, effectively integrating into our regulatory networksscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com.

A particularly intriguing discovery is the role of a recently integrated viral family, HERV-K (HML-2), in human neural development. HERV-K is the newest addition to our genome among HERVs (some insertions occurred after the human-chimpanzee split) and retains relatively intact genesscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. In pluripotent stem cells and early embryos, HERV-K sequences are transiently expressed, but they normally get silenced as cells differentiate into neuronsscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. Experiments show that if HERV-K expression is artificially kept high, it can stall the process of neurons maturingscientificarchives.com. Conversely, blocking HERV-K expression permits neural differentiation to proceed more readilyscientificarchives.com. This implies that the timely silencing of certain HERV elements is part of the program to drive stem cells toward becoming neurons. In essence, the human genome choreographs a delicate dance with these viral remnants – allowing them to be active during a narrow window to influence developmental pathways, then hushes them when their job is done.

What might these viral genes be doing in that window? One clue comes from HERV-K’s interaction with a key growth pathway. Research indicates that HERV-K activation is a key event that triggers the mTOR pathway in developing brain cells, and intriguingly, this activation pattern distinguishes humans from other primatesscientificarchives.com. The mTOR signaling pathway is known to regulate cell growth and synaptic protein synthesis, which are crucial for brain size and connectivity. The finding that HERV-K activity influences mTOR suggests that an ancient virus may have helped ramp up neural growth in our lineagescientificarchives.com. In a very real sense, a retroviral insertion may have flipped a genetic switch that contributed to a larger or more complex human brain. From a blind evolution perspective, one might marvel at the luck of such an insertion conferring a benefit. From a guided evolution perspective, one can imagine a Providential hand “allowing” this viral tweak to enable the blossoming of human cognitive capacity.

Another way that viral elements add to brain complexity is by generating neuronal diversity. Humans have a remarkable variety of neuron subtypes and subtle differences between individual brain cells (even within the same person). Part of this diversity comes from the activity of LINE-1 retrotransposons – another kind of “jumping gene” that comprises ~20% of our genomescientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. LINE-1 elements are not from retroviruses per se, but they behave similarly by copying themselves into new genomic locations. Studies show that during the formation of neurons (neurogenesis), LINE-1 elements can jump in certain neural progenitor cells, creating new insertions in the DNA of those cellsscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. As a result, each neuron may have a slightly different genome, a phenomenon called somatic mosaicism. This is especially pronounced in the hippocampus, a brain region where new neurons are born throughout life; an estimated 13.7 new LINE-1 insertions per neuron can occur in the adult human hippocampusscientificarchives.com. Why would this matter for cognition? The subtle genomic differences may lead to differences in how each neuron functions or connects, increasing the computational richness of neural circuits. It’s as if the brain seeds itself with micro-variations to explore many possible synaptic configurations, which could enhance learning capacity or resilience. This LINE-1 activity is much lower in rodents, suggesting it ramped up during primate evolution and most of all in humansscientificarchives.com. Again, a seemingly “random” process – transposons hopping in DNA – is harnessed in a precise developmental context to produce a beneficial outcome (neural diversity). It is tempting, from a faith viewpoint, to see intent in this inventiveness: evolution employing transposons to sprinkle variety into the very fabric of our brains, like an artist adding texture to a canvas.

The involvement of HERVs doesn’t end at development; there are hints it continues into the realm of higher cognitive function. One primate-specific retroviral family called MER41 has left DNA sequences (LTRs) near a number of genes tied to brain function and even to intellectual disability (ID) conditions. Remarkably, these MER41 sequences are binding sites for immune-related transcription factors (like STAT1) that also play roles in brain cellsresearchgate.net. A 2019 analysis proposed that the species-specific “domestication” of MER41 LTRs in the promoters of cognition-related genes could underlie some cognitive differences between humans and chimpanzeesresearchgate.net. In other words, certain gene networks in the human brain might be uniquely regulated by viral-derived switches, giving us neurological capabilities that apes lack. The notion that an ancient virus might have helped wire our brains for advanced cognition is astonishing – a far cry from the old assumption that viruses only inflict damage.

Of course, proper brain development requires that these volatile elements (HERVs, LINE-1, etc.) be tightly controlled. Our cells enforce strict epigenetic silencing (DNA methylation and histone modifications) on most retroelements to prevent harmful insertions or inappropriate activationscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. Yet, the control is not absolute; a slight loosening of these controls in the embryo and in certain brain regions is normal and seemingly purposefulscientificarchives.comscientificarchives.com. It’s a fine line: too little regulation and you risk genomic chaos, too much and you lose evolutionary flexibility. That fine-tuning itself speaks of balance and intentionality in biological design. Abnormal HERV expression has indeed been linked to disorders – for example, studies find elevated HERV-W env expression in schizophrenia patients’ brains and bloodpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, as well as enhanced HERV-K and HERV-H activity in autism spectrum disordermdpi.com. In these cases, genes that should have remained silent or regulated might be interfering with neural signaling or immune responses in the brain, contributing to developmental problems. The flip side of this coin is that under normal circumstances, the precise orchestration of “when and where” to keep retroviral genes quiet or let them speak is part of how a healthy human brain is built. It’s as if our neurodevelopmental program includes instructions for both using and restraining our viral inheritance. For those who see God’s hand in creation, this dual role of viruses – potential troublemakers on one hand, crucial tools on the other – resonates with a theological theme: things intended for evil being turned to good (an echo of Joseph’s words in Genesis 50:20). The very elements that could wreak havoc if unchecked are instead domesticated to add to the beauty and complexity of the human mind.

A Viral Gene that Enabled Memory: Arc

Among all the viral gifts in our genome, Arc stands out as a star player in the story of human cognition. The Arc protein (short for Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) is essential for long-term memory formation and synaptic plasticity – processes underlying learning in the brainbigthink.combigthink.com. Without Arc, animals struggle to form lasting memories of experiences; experiments in mice have shown that deleting the Arc gene leads to deficits in remembering things even a day laterbigthink.com. For years, neuroscientists knew Arc was important but were mystified by how it worked. Then came a breakthrough around 2018: Arc’s molecular structure and behavior revealed that it acts uncannily like a virus. Jason Shepherd and colleagues discovered that Arc contains domains similar to retroviral Gag proteins and that Arc self-assembles into virus-like capsids which can encapsulate RNAbigthink.combigthink.com. In fact, under an electron microscope Arc proteins form hollow shells that resemble the capsid of HIV or other retrovirusesbigthink.combigthink.com!

Why would a neuronal protein form something akin to a viral particle? It turns out this is by design (so to speak): Arc’s capsids package Arc mRNA inside and are released from neurons in extracellular vesicles, allowing the mRNA to be transported to neighboring neuronsbigthink.com. This is a novel form of intercellular communication in the nervous system – one neuron can send Arc’s genetic instructions to another, potentially to prime that neighboring cell to build certain synaptic proteins. Essentially, Arc behaves as a messenger, much like a virus spreads its genes between cells, but here it’s for the purpose of strengthening synaptic connections (the basis of learning). Shepherd’s team even demonstrated this by placing Arc capsids from one set of cells into a dish of mouse neurons and observing the transfer of RNA into those neuronsbigthink.com. They were, in their own words, “floored” by this findingbigthink.com. Arc is the first known case of a non-viral protein acting in this virus-like mannerbigthink.com. It was a vivid example of nature “borrowing” an invention from viruses and repurposing it for normal brain function.

Genetic analysis traced Arc’s origin and found that it descended from a retrotransposon in ancient ancestors of tetrapods (four-limbed animals) about 350–400 million years agobigthink.com. In other words, sometime before the split of mammals, birds, reptiles, etc., a jumping gene similar to those in retroviruses infiltrated the genome and eventually evolved into the Arc gene as we have it today. Intriguingly, a similar but independent event happened later in evolution in flies: fruit flies have their own version of Arc that also came from a retrotransposon insertion, but this occurred ~150 million years ago and is unrelated to the vertebrate Arcbigthink.com. That two separate lineages converged on recruiting a viral element for synaptic plasticity speaks to how powerful this strategy is. It’s as if evolution discovered a winning design and used it twice in different contexts. In mammals, Arc became integral to complex brain functions. We humans, with our extraordinary learning abilities, are deeply reliant on Arc: whenever our neurons strengthen a connection as we practice a skill or recall a fact, Arc is busily shuttling messages to make that change permanent.

From a guided evolution perspective, the Arc story is like a modern parable. An event that on the surface might be seen as random (a virus-like gene insertion) actually unlocked a capability that would be essential for the emergence of human intelligence. Memory and learning are foundational for language – consider that infants must remember sounds and words, and adults must accumulate vocabulary and grammar rules over years. Without robust long-term memory, true language proficiency (or culture, or technology) cannot develop. By providing a mechanism for neurons to remodel themselves and preserve those changes, Arc paved the way for creatures that could learn by experience and communicate that knowledge. It’s humbling to realize that we partly owe our ability to speak and think to an ancient “viral encounter.” One science writer put it metaphorically: our memory might exist because of a “chance encounter occurring hundreds of millions of years ago” when a retroviral ancestor inserted into our DNAbigthink.com. But was it purely chance? To people of faith, Arc can be seen as a tool placed in the evolutionary toolkit – a prepared breakthrough that would, in the fullness of time, allow minds capable of understanding divine truths and engaging in relationship with God. In Scripture, it’s said that “all things work together for good” (Romans 8:28); in Arc, we see a literal biological instance of a potentially destructive element (virus) working together for the good of creation, equipping life with memory and learning, and ultimately enabling human language, through which we can praise, question, and commune with our Creator.

Genetic Clues to the Evolution of Language

Human language is often described as a singular trait – a qualitative leap from the communication systems of other animals. While many species communicate, none have the open-ended, symbolic language that humans do, with grammar and virtually infinite expressivity. How did our brains acquire this capacity? The answer is complex and involves anatomical changes (like vocal tract modifications) as well as neurological and genetic changes. Among the genetic factors, a few key genes have been identified as critical for speech and language. The most famous is FOXP2, sometimes dubbed “the language gene.” FOXP2 was discovered two decades ago when a mutation in this gene was found to cause severe speech deficits in a British familynature.com. FOXP2 encodes a transcription factor (a protein that regulates other genes) and is expressed in several brain regions involved in coordinating speech and language processingnature.comacademic.oup.com. Humans have a unique version of FOXP2: our protein differs by two amino acids from that of chimpanzees, and these changes appeared after our lineage split from other apesacademic.oup.com. Initial studies suggested FOXP2 was under positive selection in humans, though later research refined that view; nevertheless, when the human-specific changes are introduced into mice, it subtly alters their neuron functioning and vocalizationsacademic.oup.comacademic.oup.com. FOXP2 is thus thought to be one piece of the language puzzle – helping to tune neural circuits for the fast sequence processing required in speech.

What does FOXP2 have to do with viruses? On the surface, nothing – FOXP2 is not of viral origin. However, the network of genes FOXP2 regulates, and the DNA elements that regulate FOXP2 itself, show fingerprints of transposons. Our genome’s regulatory landscape has been repeatedly rewritten by the insertions of transposable elements (including HERVs). Some of these insertions have become enhancers or silencers that shape when and where certain genes (possibly including those for neural development) are expressedscientificarchives.comresearchgate.net. Emerging research indicates that FOXP2’s function in human neurons may intersect with such elements. For instance, one study found that FOXP2 in human neuronal cells can differentially regulate a set of genes compared to chimpanzee FOXP2, and intriguingly, some of these human-specific targets are associated with MER41 retroviral LTRs in their promotersresearchgate.netresearchgate.net. In simpler terms, there are genes important for cognition that are influenced by FOXP2 and also happen to have viral DNA sequences controlling them – sequences that came from ancient infections. Furthermore, FOXP2 itself has multiple long noncoding RNAs and enhancers around it that originated from transposable elements. It’s plausible that the evolution of human speech involved not just mutations in coding genes like FOXP2, but also the exaptation of viral elements to tweak gene expression in the developing brain. As research in 2025 highlighted, the story of language evolution is tied to changes in gene regulation as much as gene sequencenature.comacademic.oup.com. The rapid wiring of neural connections for babbling infants or the finely timed motor sequences for adult speech might be aided by regulatory motifs (some of viral origin) that are unique to the human genome.

Another recent genetic discovery underscores how a single genetic change can alter vocal communication. In 2025, scientists focused on a gene called NOVA1, which is an RNA-binding protein active in the brain. They identified one particular amino acid substitution in NOVA1 that is present in modern humans but absent in Neanderthals and Denisovans (our archaic human cousins)nature.com. To test its effect, researchers used CRISPR to “humanize” mice – replacing the mouse Nova1 gene with the human version carrying this specific changenature.comrockefeller.edu. The result was striking: mice with the human-like NOVA1 exhibited different vocalization patterns compared to normal mice. Baby “humanized” mice produced more complex and varied ultrasonic calls to their mothersrockefeller.edu. Adult mice also showed altered vocal communication. This experiment suggests that the NOVA1 change could have been part of what gave modern humans a communicative edge – perhaps subtly enhancing vocal learning or the range of sounds. The authors even speculated that this single mutation might have been part of an “ancient evolutionary selective sweep… contributing to the development of spoken language” in our speciesnature.com. If we consider that Neanderthals, who lacked this NOVA1 variant, might have had different speech or cognitive traits, it’s fascinating to ponder why we got this change. Was it a lucky random mutation that spread because it improved communication? Or was it one of those “nudges” in evolution’s course that a theist might view as guided? Notably, NOVA1 is a master regulator of alternative splicing, meaning it affects how other gene transcripts are pieced together in neuronsnature.com. Changing NOVA1 could therefore rewire a whole network of gene expression. And indeed, the study found NOVA1 with the human substitution bound RNA in ways that impacted many neural genes, including those involved in vocalizationnature.com. It is a powerful example of how a minute molecular difference can cascade into a significant functional difference – in this case, possibly the difference between a fully modern language-capable brain and a nearly-modern one.

FOXP2, NOVA1, and others (like **GLUT1, a glucose transporter, or CNTNAP2, a neuron adhesion molecule) form a growing list of genes where humans show unique variants potentially tied to language or brain function. Some of these changes are point mutations; others are insertions or deletions often traceable to transposons. The interplay between these genes and viral elements underscores that the evolution of language was likely a multi-layered process. There were the structural changes (e.g., a voice box capable of nuanced sounds), the neurological changes (a bigger brain, more interconnected cortical areas), and the genetic changes (new gene variants and regulatory sequences). The viral contribution permeates the latter two: retrotransposons contributed to brain size and connectivity, and they provided regulatory diversity that could enable fine-tuned control of gene networks like those involving FOXP2. In a sense, viruses set the stage by building a more complex brain architecture, and then specific genetic tweaks (some even facilitated by viral insertions) fine-tuned that architecture for language. To believers, this layered preparation resonates with the idea of a guided process – a tapestry woven with foresight. Each virus that entered the germline, though it might have been happenstance in a microbiological sense, could be seen as a thread in God’s handiwork, one that would later reveal its purpose when human language blossomed.

Modern Viruses and the Developing Brain

Thus far we have focused on ancient viruses entrenched in our DNA. But what about viruses in the here-and-now? If past viral invasions helped mold our brains, current viral infections can still influence brain development – though usually in detrimental ways. Understanding these effects further illuminates how delicately balanced our neural development is, and by contrast, how well-integrated those ancient viral contributions must be when properly regulated.

One example that recently came to light is the effect of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) on infants. RSV is a common virus that causes cold-like symptoms and can lead to bronchitis or pneumonia, particularly in babies. A study published in 2020 revealed a concerning link between severe RSV infection in early infancy and language learning delaysnature.comnature.com. Researchers followed infants who had been hospitalized with severe RSV before 6 months of age and tested their language-related cognitive development. By 6 months old – when babies normally start tuning their brains to the sounds of their native language – those who’d had RSV showed poor distinction between native and nonnative speech sounds, compared to healthy infantsnature.com. Typically, by that age, infants become less sensitive to foreign language sounds (a sign they’re focusing on their mother tongue), but the RSV group remained indiscriminately sensitive, suggesting their phonetic learning was stuntednature.com. By 12 months old, these infants still lagged: they continued to respond equally to nonnative sounds and showed weaker communication skills, like responding to their name or babbling frequencynature.com. In effect, a single serious infection had caused “long-term language learning difficulties” during a critical window of brain developmentnature.com. The authors speculated that inflammation or the virus’s impact on the brain (RSV can occasionally enter the central nervous system) might have disrupted how memories and patterns were being etched in those crucial first monthsnature.comnature.com. This finding underscores how fragile and finely timed the process of language acquisition is – if an illness interferes, the opportunity to wire certain circuits can be missed or delayed.

Other viruses show similar patterns of developmental impact. For instance, the Zika virus epidemic of 2015–2016 tragically demonstrated that a virus can wreak havoc on brain development in the womb, causing microcephaly (an underdeveloped brain) in newborns. While Zika’s effects are more severe and structural, in terms of language the children affected often face intellectual and communicative impairments as they grow. Likewise, viruses like cytomegalovirus (CMV), when passed from mother to fetus, can lead to hearing loss and neurological damage that later impede speech. Even viruses that don’t directly infect the brain can cause intense immune reactions or high fevers that temporarily derail developmental programs.

These modern examples serve as a contrast to the ancient viral integrations we celebrate above. In our current fallen world, a viral infection in a baby can be a cause of suffering and setback, highlighting the reality of disease. Yet, intriguingly, it is the tamed viruses within us (the HERVs and others) that often respond to such assaults. There is evidence that HERV-W is abnormally activated in some neurological diseases – for example, in multiple sclerosis and possibly in autism spectrum disorder, as part of the immune-inflammatory responsemdpi.com. We might consider: in a perfectly guided evolutionary path, viruses were co-opted for good; in our day-to-day reality, viruses remain a threat when not under the genome’s control. Theologically minded readers might see this as a reflection of the broader human condition: designed for good, yet vulnerable in a fallen environment. The balance between viruses as friends or foes continues, and it challenges scientists to find ways to bolster the beneficial interactions while mitigating the harmful ones. Encouragingly, the more we learn about endogenous retroviruses, the more potential we see for medical innovation – for instance, using knowledge of viral elements to design gene therapies or to understand brain disorders at a genetic levelscientificarchives.comnature.com.

In sum, modern viruses remind us that while ancient viral integrations were crucial stepping stones in our development, only careful regulation keeps them working in harmony with our biology. When that harmony is disturbed (by external viruses or internal misregulation), development can be impaired. This dual aspect again points to a creative wisdom: the same class of entities (viruses) can be agents of creation or destruction. The difference lies in context and control. It’s a sobering and awe-inspiring thought that God’s evolutionary design had to incorporate such volatile elements – harnessing their power for creativity while containing their potential for harm. The successful integration of retroviral elements into our lineage, culminating in something as sublime as human language, speaks to an overarching guidance that is able to “write straight with crooked lines,” to borrow a phrase. Even the smallest of viruses can thus be part of a much grander story.

Epilogue: The Fingerprints of Providence

Contemplating the journey from viral infection to human intellect evokes a sense of wonder. What are the odds that random retroviral insertions would land in just the right spots to boost brain size, wire new circuits, or create a protein that carries neuronal messages? The science we’ve discussed paints a picture of evolution that is not a simple linear ascent, but a tapestry woven with unexpected threads – viruses being among the most unexpected of all. To a secular scientist, these findings might simply illustrate nature’s fecund inventiveness: life makes do with what it encounters, even turning viruses into tools. To people of faith, however, there is a familiar voice echoing through this narrative: a voice that says, “Behold, I make all things new.” The concept of theistic evolution holds that God created living beings through evolutionary processes – purpose and chance mingled in a way ultimately orchestrated by divine wisdom. In the repurposing of retroviruses, we see a tangible instance of this principle. What once caused disease in our distant ancestors became, by the time humanity arrived, an integral part of what makes us alive and conscious. Such redemption of chaos into order is, for believers, the signature of the Creator.

Consider again the Arc protein. If one were to look at a primitive amniote 350 million years ago that first gained this strange gene, one might think it a fluke. Fast-forward to the present, and that “fluke” has given rise to memories, songs, stories – the very fabric of human culture – by enabling brains to store information long-term. Arc is like a keystone laid in deep time, without which the arch of human cognition might collapse. Or think of the moment an ancient primate’s genome was invaded by HERV-K. Perhaps it caused a few harmful mutations at first. But eventually, through God’s providence (working through natural selection), that very sequence became a switch to activate growth in the developing human cortexscientificarchives.com. Such trajectories speak to an end-directedness in evolution, what Christian thinkers might call teleology. The end (telos) in this case was the emergence of a being capable of language, reason, and love – Homo sapiens – and one of the means was the humble virus.

For the faith-based community, stories like these can bridge the perceived gap between science and faith. They show that accepting evolution does not require excluding God’s guidance; on the contrary, the depth of complexity and ingenuity in evolutionary history can inspire even greater reverence for the Creator. If evolution were purely blind, it is hard to fathom it stumbling upon such elegant solutions as Arc or syncytin. The fact that evolution “chose” viruses as instruments to further life’s progress hints at a higher choosing. It calls to mind the biblical motif that “the stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone” (Psalm 118:22). Viruses, essentially rejected scraps of genetic material, ended up cornerstone contributions to critical structures – the placenta that nourishes us, the neurons that remember, the networks that enable speech. This inversion – the lowly being lifted to the lofty purpose – is deeply resonant with a theistic worldview.

None of this is to deny the reality of random mutations, natural selection, or the genuine contingency in evolutionary history. Theistic evolution doesn’t claim that God micromanaged every mutation, but rather that no mutation lies outside of God’s sustaining will. In other words, randomness in nature does not equate to purposelessness in an ultimate sense. The retroviruses did what retroviruses do – insert DNA randomly. But the outcomes were folded into the story of life’s development in such a way that today we can see meaning in them. As a tapestry viewed from the back looks like a mess of threads, but from the front reveals a pattern, so too evolution’s weave of viral DNAs looks “messy” until we perceive the emergent image – the image of rational, communicative beings made in God’s likeness.

As we marvel at this convergence of virology, neuroscience, and theology, we also stand humbled. Our capacity for language – to speak to one another, to speak to God in prayer – is built upon molecular events written into our very DNA by ancient viral encounters. It’s a reminder that we are fearfully and wonderfully made, but also that we carry in our biological story the record of struggle and suffering (for what is a virus but a reminder of plague and death?). Guided evolution is not a simplistic, idyllic process; it is dramatic, at times perilous, but under a divine Shepherd it arrives at green pastures. In our genome, we bear the scars of past infections yet also the seal of creative redemption of those scars. The next time you recall a cherished memory or say “I love you” to someone, consider that an ancient virus is partly to thank for that miraculous ability – and perhaps, in that realization, hear the whisper of a Designer who foresaw how even a virus could serve love’s purpose.

In conclusion, the role of retroviruses in human brain development and language is a testament to life’s remarkable capacity to bring forth good from unlikely sourcesbigthink.compdb101.rcsb.org. It underscores an evolutionary narrative that is entirely consistent with a Creator who imbues creation with freedom and potential, yet guides it toward fulfillment. The evidence does not point to a brutish, directionless process, but to a tapestry of intelligent agency working through natural mechanisms. For believers seeking harmony between faith and science, what better example than the virus – once seen only as enemy, now recognized as a hidden ally – to illustrate that evolution is neither godless nor purposeless? Instead, it can be viewed as God’s ingenious method of creation, in which every creature, even the tiniest virus, has a role to play. In the grand story of life, viruses helped script the prologue to our humanity; and in that, we might discern not only the blind forces of nature, but the writing of the Logos, the Divine Word through whom all things were made.

Sources:

bigthink.combigthink.com; scientificarchives.com; nature.com; nature.com; nature.comnature.com; researchgate.net; pdb101.rcsb.org; pdb101.rcsb.org.

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment