Epigraph:

الَّذِي خَلَقَ سَبْعَ سَمَاوَاتٍ طِبَاقًا ۖ مَّا تَرَىٰ فِي خَلْقِ الرَّحْمَٰنِ مِن تَفَاوُتٍ ۖ فَارْجِعِ الْبَصَرَ هَلْ تَرَىٰ مِن فُطُورٍ

ثُمَّ ارْجِعِ الْبَصَرَ كَرَّتَيْنِ يَنقَلِبْ إِلَيْكَ الْبَصَرُ خَاسِئًا وَهُوَ حَسِيرٌ

He is the Mighty, the Forgiving; Who created the seven heavens, one above the other. You will not see any flaw in what the Lord of Mercy creates. Look again! Can you see any flaws? Look again! And again! Your sight will turn back to you, weak and defeated. (Al Quran 67:3-4)

Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Part I: The Bristol Crucible – The Genesis of Solitude

1.1 The Architecture of Silence

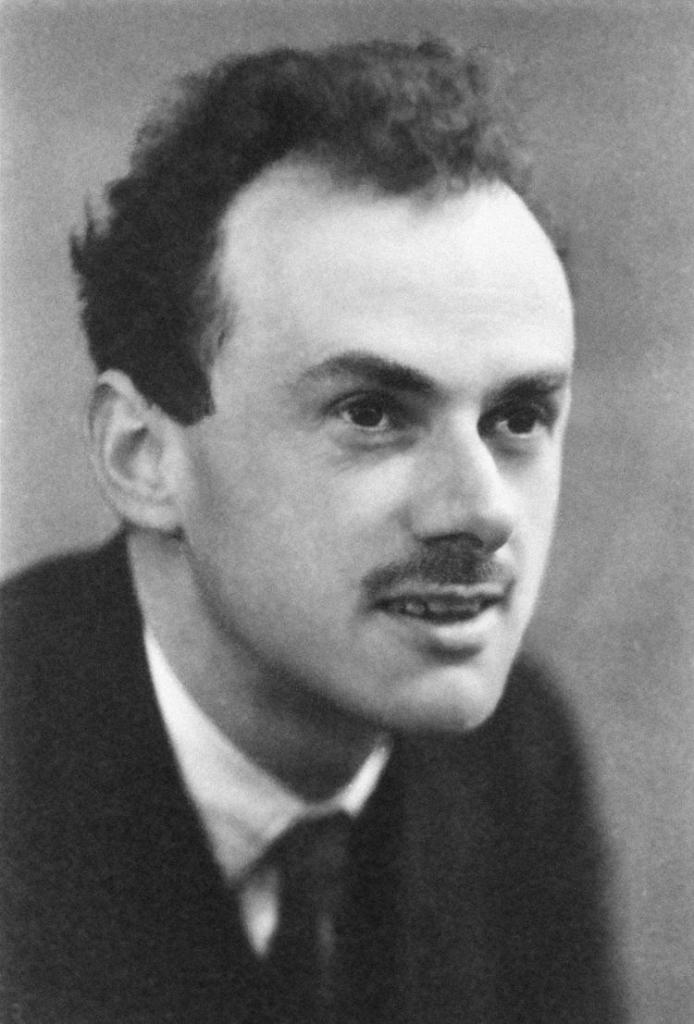

To understand the mind of Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac, one must first inhabit the silence that forged him. Born on August 8, 1902, in the industrial port city of Bristol, England, Dirac entered a world that was strictly partitioned—not by physical walls, but by the invisible, impenetrable barriers of language and paternal authority. His father, Charles Dirac, was a Swiss immigrant from the Valais canton, a man of rigid discipline and authoritarian temperament who taught French at the Merchant Venturers’ Technical College. His mother, Florence Holten, was a librarian’s daughter from Cornwall, described as submissive and overshadowed by her husband’s domineering presence.1

The Dirac household at 6 Monk Road was defined by a peculiar linguistic regime imposed by Charles. In a bid to ensure his children learned his native tongue, Charles decreed that Paul, his middle child, must speak to him only in French. This was not merely an educational strategy; it was a test of compliance and a mechanism of control. Paul, possessing a mind that craved precision and finding his command of French insufficient to express the complex, crystalline thoughts already forming in his intellect, chose the path of least resistance: total silence. He later reflected on this formative trauma with characteristic detachment, noting, “I found I couldn’t express myself in French, so I remained silent”.2

This enforced mutism transformed the dining table—traditionally the locus of familial bonding—into a site of psychological siege. While his mother and siblings (his older brother Felix and younger sister Beatrice) often ate in the kitchen to avoid Charles’s scrutiny, Paul was required to dine with his father. These meals passed in a heavy, suffocating quiet, broken only by the necessary monosyllables of the French language. This suppression of speech had a profound neurological and psychological effect on the young Dirac. Deprived of the chaotic, corrective feedback of social chatter, his mind turned inward. He began to view the world not as a narrative constructed of words, but as a structure built of logical relations. He learned to trust the internal consistency of his own thoughts over the messy, ambiguous data of human interaction.3

The tragedy of the Dirac household was not limited to silence. Paul’s relationship with his older brother, Felix, was marked by a shared suffering that yielded divergent outcomes. Felix, described as “placid” and a “dreamer” who struggled with the rigid expectations of their father, eventually took his own life—a catastrophic event that Paul would later recount to his wife with a terrifying lack of visible emotion, seemingly having processed the grief entirely through the logic of inevitability.4 The shadow of his father was so long that, upon Charles’s death years later, Paul wrote to his wife, “I feel much freer now, and I am my own man,” a sentence that carries the weight of decades of repressed autonomy.2

1.2 The Engineering of a Mind

It is a common misconception to categorize Dirac purely as a mathematician or a theoretical physicist. His intellectual pedigree was, in fact, rooted in the pragmatic soil of engineering. In 1918, at the age of 16, he enrolled at the University of Bristol to study electrical engineering.1 This decision, driven by his father’s practicality, would prove to be the single most important factor in distinguishing Dirac’s physics from the abstract formalism of his continental peers like Heisenberg and Pauli.

The engineering curriculum of the early 20th century was not a study of abstract fields; it was a tactile engagement with the limits of materials and the utility of approximation. Dirac learned to view equations not as sacred texts that must be perfectly solved, but as tools to describe physical systems. He absorbed the engineer’s creed: a solution that works is a good solution, even if the mathematics is “illegal” by the standards of pure analysis. This mindset is evident in his later development of the “delta function”—a mathematical monstrosity that is zero everywhere except at the origin, where it is infinite, yet integrates to one. Mathematicians were horrified; engineers, who used “impulses” daily, understood it intuitively. Dirac had the courage to use the delta function because his engineering training taught him that the robustness of the result justified the method.5

Furthermore, his training involved a rigorous course in projective geometry—a branch of mathematics that deals with the properties of geometric figures that remain invariant under projection (like a shadow cast on a wall). This visual, geometric training allowed Dirac to “see” the structure of the quantum world in a way that others could not. While Heisenberg was lost in matrices and Schrödinger was thinking in waves, Dirac was visualizing vectors in infinite-dimensional spaces, rotating and projecting them with the intuitive ease of a draftsman.8

The following table contrasts the educational backgrounds of the quantum founders, highlighting Dirac’s unique position:

| Physicist | Primary Training | Intellectual Style | Approach to Math |

| Paul Dirac | Electrical Engineering | Structural / Geometrical | Pragmatic: “It works, so it is true.” |

| Werner Heisenberg | Theoretical Physics | Algebraic / Abstract | Formalistic: “The observables define the theory.” |

| Erwin Schrödinger | Mathematical Physics | Wave Mechanics / Classical | Conservative: “Must match classical intuition.” |

| Wolfgang Pauli | Theoretical Physics | Critical / Logical | Rigorous: “God does not sin against math.” |

1.3 The Transition to Cambridge

In 1921, Dirac graduated with a first-class honors degree in electrical engineering. However, the post-war economic slump meant that jobs were scarce. Unable to find employment as an engineer, and failing to win a scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge, due to the inadequacy of the offered funds, he accepted a free place to study mathematics at Bristol for two years. It was here that he first encountered the theory of relativity, a subject that captivated his imagination and prepared him for his eventual move to Cambridge in 1923.1

Arriving at Cambridge as a research student under Ralph Fowler, Dirac was a complete unknown—a quiet, socially awkward young man with a provincial accent and a strange background in engineering. Yet, he possessed a weapon that the polished graduates of Eton and Harrow lacked: a mind completely unencumbered by the philosophical baggage of the past. He did not care about the “meaning” of physics in the philosophical sense; he cared about the structure. This clarity of vision would soon allow him to see through the fog of the “Old Quantum Theory,” a patchwork of classical mechanics and ad-hoc quantum rules that was slowly collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions.9

Part II: The Architect of the Quantum Cathedral

2.1 The Sunday Walk and the Commutator

The breakthrough that launched Dirac into the pantheon of physics occurred on a Sunday in September 1925. He had received proofs of a paper by Werner Heisenberg, which introduced a strange new way of calculating atomic transitions using arrays of numbers (matrices). Heisenberg was apologetic about the fact that his math was non-commutative—that is, $A \times B$ did not equal $B \times A$. To most physicists, this was a bizarre nuisance.

To Dirac, it was a revelation. During a solitary walk in the Cambridge countryside, he mulled over the structure of this non-commutativity. His mind, trained in the dynamics of classical mechanics, drifted to the “Poisson brackets”—operations used in classical Hamiltonian mechanics to describe the evolution of a system. In a flash of insight, he realized that the difference between $A \times B$ and $B \times A$ in quantum mechanics was perfectly analogous to the Poisson bracket in classical mechanics, multiplied by a factor of Planck’s constant and the imaginary unit ($i\hbar$).

This was the “Rosetta Stone” of quantum mechanics. It meant that the strange new quantum laws were not arbitrary; they were a generalization of classical laws. Dirac had found the structural link between the world of the everyday and the world of the atom. He rushed back to his room, but it was late, and he was unable to verify the formula until the libraries opened the next morning. The “Fundamental Equation of Quantum Mechanics” was born from this silence and solitude.10

2.2 The Equation of Destiny (1928)

If 1925 was the spark, 1928 was the fire. The physics community was divided. Schrödinger had a wave equation that was easy to visualize but failed at high speeds (relativity). Heisenberg had matrix mechanics that worked but was abstract and ugly. The goal was to unify quantum mechanics with Einstein’s special relativity.

Dirac approached this problem with the aesthetic criteria of a pure mathematician. He sought an equation that was “linear” in space and time—simple, symmetric, and elegant. He played with 4×4 matrices (now known as Dirac matrices or Gamma matrices), manipulating them until they fit the relativistic requirement $E^2 = p^2c^2 + m^2c^4$.

The result was the Dirac Equation:

$$(i\gamma^\mu\partial_\mu – m)\psi = 0$$

This equation is widely considered the most beautiful in the history of physics. It achieved what should have been impossible:

- It was fully consistent with Special Relativity.

- It automatically explained “spin”—a property of the electron that others had to add by hand.

- It explained the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum with unprecedented accuracy.

However, the equation came with a terrifying price. It predicted four solutions. Two corresponded to the electron with positive energy (spin up and spin down). The other two corresponded to an electron with negative energy. In classical physics, negative energy is meaningless—it implies a particle that gains speed when you try to stop it.

Most physicists, including Heisenberg and Pauli, dismissed these “negative energy solutions” as a mathematical artifact, a glitch to be ignored. Dirac, however, was incapable of ignoring the mathematics. He believed that if the equation was beautiful, it must be true. This led to the “Hole Theory.” He imagined that the vacuum of space was not empty but filled with an infinite sea of negative-energy electrons (the “Dirac Sea”). A “hole” in this sea would appear as a particle with positive energy and positive charge.

In 1931, driven by the inexorable logic of his own equation, Dirac published a paper predicting the existence of a new particle: the “anti-electron.” He wrote, “We should not expect to find any of these [holes] in nature… but if they exist, they would be a new kind of particle, unknown to experimental physics, having the same mass and opposite charge to an electron”.11

Two years later, Carl Anderson detected this particle in cosmic rays and named it the positron. Dirac had discovered Antimatter—half of the potential reality of the universe—using nothing but a pencil and a faith in the architecture of mathematics. This moment cemented his status as the “Theorist’s Theorist.” He had proven that mathematics was not just a description of reality, but a probe that could reach further than any telescope.10

Part III: The Theology of the Atheist – A Critical Commentary

3.1 The “Militant Atheist” of 1927

To fully appreciate Dirac’s later statements about God, one must confront the ferocity of his early atheism. The young Dirac, liberated from his father’s house and empowered by the clarity of science, viewed religion with undisguised contempt.

The definitive anecdote comes from the 1927 Solvay Conference. In the lounge of the Hotel Metropole, a group of young physicists including Heisenberg, Pauli, and Dirac were discussing Einstein and Planck’s views on religion. Dirac, usually silent, erupted into a monologue. He argued:

“I cannot understand why we idle discussing religion. If we are honest—and scientists must be—we must admit that religion is a jumble of false assertions, with no basis in reality. The very idea of God is a product of the human imagination… I can’t see any sign of a God who concerns himself with our daily actions.” 14

He went further, analyzing religion as a socio-political tool used by the ruling class to subdue the proletariat—a view likely influenced by the Marxist currents popular among intellectuals of the era. He concluded that “religion is a kind of opium for the people” (paraphrasing Marx).13

The intensity of this outburst shocked his colleagues. Wolfgang Pauli, a man of deep psychological insight, waited for Dirac to finish and then delivered the famous witticism:

“Well, our friend Dirac has a religion, and the basic postulate of this religion is: ‘There is no God, and Dirac is His prophet.’” 15

This remark was profound. It identified that Dirac’s atheism was not a passive lack of belief, but a positive dogma. He believed in the non-existence of God with the same fervor that a fundamentalist believes in scripture. His “God” was Logic, and any deviation from it—such as the messy contradictions of religious history—was heresy.

3.2 The Evolution: “God is a Mathematician” (1963)

Thirty-six years later, in May 1963, Dirac wrote an article for Scientific American titled “The Evolution of the Physicist’s Picture of Nature.” The tone is radically different. The militant fire is replaced by a contemplative reverence for the mystery of existence. It is here that he delivers the quote that has puzzled biographers and theologians alike:

“One could perhaps describe the situation by saying that God is a mathematician of a very high order, and He used very advanced mathematics in constructing the universe.” 17

He continues:

“Our feeble attempts at mathematics enable us to understand a bit of the universe, and as we proceed to develop higher and higher mathematics we can hope to understand the universe better.” 18

Commentary and Analysis:

Is this a conversion? Absolutely not. There is no evidence Dirac ever accepted the tenets of any organized religion or believed in a personal deity who hears prayers. So what does this statement mean?

- Metaphor for Structural Realism: Dirac is using “God” as a metaphor for the Fundamental Order. In the 1920s, he destroyed the “Religious God” (the anthropomorphic father-figure). In the 1960s, he erected the “Mathematical God” (the source of cosmic symmetry). This is a shift from criticizing the sociologist’s religion to affirming the physicist’s metaphysics.

- The Argument from Design (Revisited): The classical Argument from Design says, “The eye is complex, so there must be a Watchmaker.” Dirac’s argument is, “The math is beautiful, so there must be a Geometer.” He was struck by the fact that the universe didn’t just follow “rules”; it followed the most elegant rules possible.

- The Schrödinger Parable: In the same article, Dirac recounts how Schrödinger found his equation. Schrödinger first found a relativistic equation (Klein-Gordon) but abandoned it because it didn’t fit the data (due to spin). He settled for a “uglier” non-relativistic equation that fit the data. Dirac argues this was a mistake. Schrödinger should have had more faith in the beauty of the math than the accuracy of the data. This anecdote serves as the exegesis for the “God is a Mathematician” quote: The “God” Dirac refers to is the principle that Beauty is Truth.18

3.3 The “Religion of Science” and Mathematical Platonism

Dirac’s worldview aligns with Mathematical Platonism—the belief that mathematical objects (numbers, vectors, groups) exist independently of the human mind.

- Constructivism says: We invent math to describe the world. (Math is a map).

- Platonism says: Math exists in a separate realm; the world is a shadow of it. (Math is the territory).

Dirac was an arch-Platonist. He felt he did not “invent” the Dirac equation; he “discovered” it. It was already there, waiting in the limestone of reality, and he merely brushed away the dirt.

This leads to the “Religion of Science”.20 For Dirac, doing physics was a sacramental act. It was a form of communion with the “Mathematical God.” The rigorous application of logic was a form of prayer; the discovery of a new law was a revelation.

His friend and colleague, Eugene Wigner, famously wrote about “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”.22 Dirac’s quote is the direct answer to Wigner. The effectiveness is not unreasonable if the substrate of the universe is mathematics. If God is a mathematician, then the fact that math works is a tautology.

3.4 Insights from Research: The Autistic Connection to the Divine

Modern retrospective analysis suggests Dirac was neurodivergent, likely on the autism spectrum.1 This provides a critical lens for understanding his theology.

- Social Blindness: Dirac couldn’t “read” people. He found human behavior baffling, irrational, and noisy.

- Mathematical Clarity: He found math perfectly readable. It was consistent, honest, and noise-free.

- The Psychological Transfer: It is plausible that Dirac projected his need for order onto the cosmos. A “Personal God” (who has emotions, anger, jealousy) would be just as baffling to Dirac as a human father. A “Mathematical God” (who is pure consistency) was a deity he could love and understand.

- Insight: Dirac’s “God” is the ultimate safe space for the autistic mind—a being of pure structure, devoid of ambiguity.

Part IV: The Engineer of the Infinite – Later Years and Legacy

4.1 The War and the Isotopes

While Dirac is celebrated for his abstract theory, his engineering background resurfaced during World War II. He was involved in the theoretical work for isotope separation, crucial for the Manhattan Project. Specifically, he worked on the statistical methods for separating Uranium-235 using gas centrifuges. This work, often overshadowed by Oppenheimer and Fermi, demonstrates the “Engineer Dirac”—the man who could descend from the nth dimension to optimize the separation of heavy metals.8

4.2 The Critique of QED: “It is Ugly”

In his later years (post-1950s), Dirac became a critic of the very field he helped create: Quantum Electrodynamics (QED). The theory, developed by Feynman, Schwinger, and Tomonaga, was incredibly successful at predicting experimental results (like the magnetic moment of the electron). However, the equations were plagued by infinities. To get the right answer, physicists had to use a technique called “renormalization”—essentially subtracting one infinity from another to get a finite number.

Dirac hated this. He called it “brushing infinity under the rug.” He reverted to his fundamental creed: Mathematical Beauty.

- “I must say that I am very dissatisfied with the situation,” he said, “because this so-called ‘good theory’ involves neglecting infinities which appear in its equations, neglecting them in an arbitrary way. This is just not sensible mathematics. Sensible mathematics involves neglecting a quantity when it is small – not neglecting it just because it is infinitely great and you do not want it!”.10

He spent his final decades in a lonely pursuit of a “clean” QED, becoming increasingly isolated from the mainstream physics community which had accepted renormalization as a necessary tool. This period illustrates the rigidity of his “religion.” Just as he rejected the Christian God for lack of evidence, he rejected the QED “God” for lack of elegance, even though QED worked perfectly in the lab.

4.3 The Twilight in Florida

In 1971, Dirac retired from Cambridge and moved to Florida State University in Tallahassee, drawn by the warmer climate and a position offered by his former student. There, in the humid quiet of the American South, the “Silent Man” softened. He was known to take long walks, occasionally speaking with students, though his brevity remained legendary.

He died on October 20, 1984. His grave in Tallahassee simply reads:

$$i\gamma^\mu\partial_\mu\psi – m\psi = 0$$

Even in death, he chose to be represented not by a scripture, but by the equation that was his prayer to the universe.3

Part V: Conclusion – The Prophet of Symmetry

Paul Dirac remains the strangest figure in the history of science. He was a man who spoke little, but whose silence spoke volumes. He was an engineer who built bridges to the invisible; an atheist who found God in the calculus; a revolutionary who ended his life as a conservative critic of his own revolution.

His legacy is not just the equation that bears his name, or the prediction of antimatter. It is a methodological legacy. He taught physics that Symmetry is a guide to truth. This belief drives the search for String Theory and Grand Unified Theories today. Every time a physicist argues that a theory is “too beautiful to be wrong,” they are echoing the prophet of Bristol.

The “God” that Dirac spoke of—the Mathematician of a very high order—is still the God that modern physics worships. It is a God of Invariance, a God of Gauge Symmetry, a God who does not play dice, but who plays a game of such complex geometry that we are only just beginning to learn the rules. In the end, Pauli was right: Dirac was a prophet. He was the prophet of the hidden geometry of the world, and his scripture was written in the ink of algebra, indelible and eternal.

Appendix: Comparative Analysis of Religious and Scientific Views

The following table synthesizes the complex relationship between the “Founding Fathers” of Quantum Mechanics, their religious backgrounds, and their scientific philosophies. This comparison highlights Dirac’s unique position as a “Structuralist Atheist.”

| Feature | Paul Dirac | Werner Heisenberg | Wolfgang Pauli | Erwin Schrödinger |

| Religious Background | Secular/Protestant (Nominal) | Lutheran | Catholic / Jewish | Catholic (Cultural) |

| Adult View | Atheist / Structural Platonist | Christian Mystic / Platonist | Jungian Mystic / “The Shadow” | Vedantic Hindu (Monist) |

| God Concept | “The Great Mathematician” | ” The Central Order” | “The Spirit of Matter” | “Atman = Brahman” (Self is God) |

| View of Math | Ontological (Math is reality) | Epistemological (Math describes knowledge) | Symbolical (Math is an archetype) | Representational (Math models waves) |

| Key Quote | “God is a mathematician of a very high order.” | “The first gulp turns you atheist; the bottom waits God.” | “There is no God and Dirac is his prophet.” | “I am God.” (Deus Factus Sum) |

| Attitude to Miracle | Rejects Miracles, accepts “Spooky” math | Accepts mystery | Fascinated by synchronicity | Denies dualism entirely |

Data Cluster Analysis: The “Unreasonable Effectiveness”

Based on 22 and 23, we can map the different explanations for why math works, placing Dirac firmly in the “Mathematical Universe” camp (similar to Max Tegmark’s later views).

- The Puzzle: Why does the equation for a spinning top also describe a subatomic particle?

- Wigner’s View: It is a “miracle” and a “gift” we do not understand.

- Einstein’s View: It is a result of the human mind seeking order (Constructivism).

- Dirac’s View: The universe is made of math. We are uncovering the “bones” of reality.

The “French Table” Impact Analysis

Based on 1, the following causal chain can be inferred regarding Dirac’s psychology:

- Input: Paternal authority demands communication in a non-native language (French).

- Constraint: Young Paul lacks vocabulary/fluency + fears error/punishment.

- Reaction: Strategic withdrawal into silence (Minimax strategy: Minimize speech to minimize error).

- Adaptation: Internalization of thought. Development of visual/symbolic processing to replace verbal processing.

- Outcome: A mind that views words as imprecise/dangerous and symbols/equations as safe/precise.

- Scientific Result: The “Dirac Style” of physics—extreme brevity, removal of all superfluous words, reliance on pure mathematical structure.

This analysis suggests that the “French Rule” was the accidental crucible that forged the specific cognitive tools necessary for Quantum Mechanics. Without that trauma, Dirac might have been a loquacious engineer, and the positron might have remained unknown for decades.

Leave a comment