Presented by Zia H Shah MD

Abstract

This article offers a comprehensive commentary on Qur’an 39:27–29 through psychological, philosophical, and theological lenses, highlighting its deep connection with Qur’an 4:82. These Quranic verses collectively emphasize the unity and consistency of divine truth, using the parable of a slave with multiple masters versus one with a single master to illustrate how contradictory authorities breed incoherence, whereas devotion to the One God yields inner peace and logical consistency. We expound how the “multiple partners” in 39:29 symbolize conflicting ideas that result in cognitive dissonance and turmoil, in contrast to the harmonious clarity that comes from serving a single, unifying Truth. Drawing parallels to Qur’an 4:82 (“If it were from other than Allah, you would have found much contradiction”), we explore the unity of knowledge across all domains – science, philosophy, and theology – as a hallmark of the Quran’s divine origin and a blueprint for human understandingthequran.lovethequran.love. Insights from classical Islamic scholarship and modern thought (including analyses of double-bind psychology, the law of non-contradiction, and the coherence of monotheism) are interwoven throughout. In essence, the Quran’s insistence that truth cannot contradict truth becomes a guiding principle: it invites believers and skeptics alike to reflect deeply, resolve apparent contradictions, and align their worldview under a single, contradiction-free paradigm. The commentary also discusses how living by these verses can bridge the divide between atheists and theists and foster interfaith dialogue, since a commitment to consistency and reason in matters of faith builds common ground. An epilogue ties together the themes, suggesting that acting on the Quran’s call to unity – of God, self, and knowledge – leads to personal tranquility and a more coherent understanding of reality, wherein faith and reason reinforce each other in the pursuit of truth.

Introduction

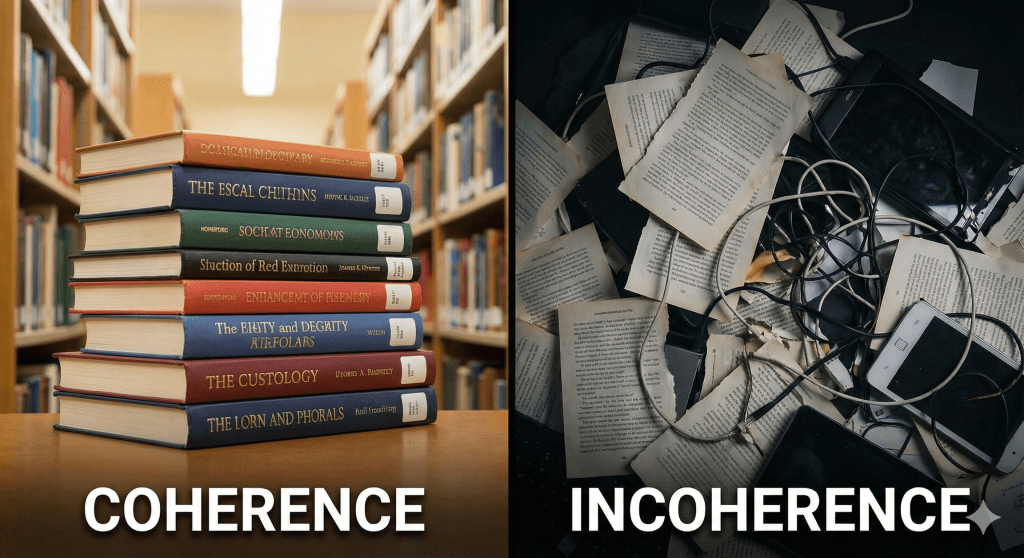

In the Quran, reflection and reason are paramount. Surah Al-Zumar (39:27–29) encapsulates this by presenting both a declaration and a parable that together champion the clarity, consistency, and unity of the divine message. First, the Quran asserts that it has “put forth for humanity every kind of parable” so that people may reflect, and that it is “a Quran in Arabic, without any crookedness, so that they may be mindful of God” (39:27–28)thequran.lovethequran.love. In other words, the scripture provides abundant examples and teachings, all delivered in a clear language and form with no deviation or inconsistency in themthequran.love. Immediately following this, verse 39:29 offers a striking parable about a slave who serves many quarrelsome masters versus a slave devoted to one master, then pointedly asks: “Are the two equal in comparison?”thequran.love. Through this simple but powerful image, the Quran invites us to ponder the difference between disunity and unity – whether in worship, belief, or sources of guidance – and to recognize the superior ease and coherence that comes with singularity.

The theme emerging from these verses is one of divine consistency. The Quran portrays itself as straight and self-consistent, free of the contradictions that one would expect if it were a patchwork of multiple sources or authors. Indeed, it elsewhere challenges skeptics in the same spirit: “Will they not then reflect on the Quran? If it had been from anyone other than Allah, they would surely have found in it much contradiction.” (Qur’an 4:82)thequran.lovethequran.love. The resonance between 39:29’s parable and 4:82’s statement is profound – both convey that truth, when from the One Almighty, is inherently one and without discrepancy, whereas multiplicity of unchecked sources leads to discordance. As one modern scholar observes, “the verse [4:82] in effect teaches a rational criterion for truth in scripture – non-contradiction”thequran.love. In the pages that follow, we will explore how Qur’an 39:27–29, illuminated by Qur’an 4:82, provides insight into three dimensions of human understanding:

- Psychologically, it addresses the conflict and cognitive dissonance that arise from holding or obeying contradictory directives, illustrating how a consistent divine guidance alleviates inner turmoilthequran.lovethequran.love.

- Philosophically, it invokes the principle of non-contradiction as a test of truth, implying that a universe governed by one Logos (Divine Reason) will be coherent – a concept that extends to the unity of scientific and spiritual truthsthequran.lovethequran.love.

- Theologically, it underscores tawḥīd (the oneness of God) as the foundation for a coherent belief system, and it invites a critical evaluation of doctrines or interpretations – across all religions – that lead to logical paradoxes or inconsistenciesthequran.lovethequran.love.

By examining each of these facets, we shall see that the Quran’s vision of one truth is not only a theological doctrine but a holistic approach that heals psychological strife, satisfies the philosophical demand for coherence, and solidifies the credibility of revelation. In doing so, we will also discuss how applying these Quranic principles can build bridges between faith and reason, between theists and atheists, and among various religious traditions. The journey begins with the Quran’s own parable of clarity and consistency in 39:27–29.

Qur’an 39:27–29 – Clarity, Consistency, and the Parable of One Master

“We have certainly presented to humanity every kind of parable in this Quran, so that they may take heed – a Quran in Arabic, without any crookedness therein, in order that they may be conscious of God. Allah sets forth the parable of a slave owned by several quarrelsome masters, and a slave owned by only one master. Are they equal in condition? Praise be to Allah! But most of them do not know.” (Qur’an 39:27–29)thequran.lovethequran.love

These verses open by emphasizing the universality and completeness of the Quran’s guidance: it contains examples and lessons of every kind, crafted in a clear and straightforward manner. The phrase “without any crookedness” (Arabic: ghayra dhī ‘iwajin) in 39:28 is especially notable. Classical commentators interpret “no crookedness” to mean the Quran has no deviation, distortion, or inconsistency in its teachingsthequran.lovethequran.love. In other words, it is a straight path of truth, unmarred by the errors or contradictions that typically plague human discourse. As one scholar notes, “God’s word contains no distortions or errors; it is a ‘straight path’ guiding to truth.”thequran.love By stressing its own lack of ‘iwaj (crookedness), the Quran assures the reader that its content is wholly reliable and internally harmonious – a point reinforced in the very structure of its arguments. Immediately, the text links this perfection of form with its purpose: “so that they may be conscious of God.” Clear and consistent guidance is thus tied to spiritual benefit; the Quran’s coherence is a means to lead people to a coherent relationship with the Divine.

To cement this message, verse 39:29 presents a vivid parable. Imagine, it says, two individuals: one is a slave trying to serve many masters who are quarreling with one another, and the other is a slave devoted to only one master. “Are those two equal in comparison?” the verse pointedly asksthequran.love. The implied answer is an emphatic no. Anyone can intuit that a servant with multiple bosses barking different orders will live in confusion and stress, while a servant answering to a single, wise master will live in focused peace. The Quran concludes the parable with “Al-ḥamdu lillāh” (Praise be to God) and a lament that most people do not understand this obvious truth.

The meaning of this parable operates on multiple levels:

- Theological (Literal) Level: Early Islamic authorities, including the Prophet’s cousin Ibn ‘Abbās, understood this as an analogy for polytheism versus monotheismthequran.love. The mushrik (idolater or polytheist) who tries to please many imaginary gods is like the slave with many masters – pulled apart by disparate and often capricious demands. By contrast, the sincere muwahhid (monotheist) devoted to the One true God is like the slave with one master – focused, directed, and at peace. “This ayah is the parable of the idolator and the sincere believer,” explains one classical commentary, “the former is beset by internal conflict, and the latter by contrast enjoys inner consistency and tranquility.”thequran.love The various false gods of polytheism (or errant beliefs) do not have a unified will, resulting in contradictory expectations on the devotee. But the One God of Islamic monotheism is Al-Ḥaqq (The Truth) – utterly consistent and just – so serving Him alone brings a coherent purpose to life. The Quran elsewhere makes a similar rational argument: “Had there been in the heavens or earth any gods besides Allah, both would surely have fallen into chaos…” (21:22)thequran.love. Multiple deities with independent powers would clash and ruin the order of the cosmos, a notion mirrored by the strife of the “quarrelsome masters” in this parable. Thus, unity (of God) is directly linked to harmony (in creation and guidance), whereas multiplicity of gods logically yields disorderthequran.love.

- Psychological (Metaphorical) Level: Beyond formal theology, the parable speaks to the human psyche. The slave with many masters can symbolize a person torn between conflicting priorities or beliefs – for example, someone trying to satisfy contradictory societal expectations, or a person internally divided by various passions and doubts. Such a person experiences what modern psychology calls inner conflict or even cognitive dissonance – the mental distress of entertaining inconsistent beliefs or goalsthequran.lovethequran.love. By contrast, the slave with one master represents a person who has attained unity of purpose – their heart, mind, and will are devoted to a singular guiding principle (in the Quran’s intent, devotion to God). This individual achieves a psychological wholeness that the conflicted person lacks. As the verse implies, a soul unified in loyalty to the Truth has a tranquility that a divided soul can never attainthequran.love. In simple terms, “worshiping one God leads to a coherent life, whereas serving many masters – whether literal gods or figurative obsessions – leads to chaos within.”thequran.love The mention of the masters being “quarrelsome” (literally, disputing with each other) is key – it indicates that the demands placed on the slave are not just numerous but fundamentally at odds with each other. This is akin to a child raised by double-binding parents who give contradictory messages; the child becomes anxious and confused because they cannot satisfy one instruction without violating anotherthequran.lovethequran.love. Modern psychology recognizes this as a form of emotional trauma – Gregory Bateson famously linked such double-bind situations to anxiety and dysfunction, noting that a person caught in them “receives two or more conflicting commands… such that any response they make is ‘wrong,’” leaving them in no-win scenariosthequran.love. The Quran’s parable anticipated this insight: a human mind pulled by incoherent commands (many masters) is essentially trapped in a no-win situation, whereas a mind devoted to a coherent command (one master) is liberated to find clear direction.

- Logical/Philosophical Level: The scenario also exemplifies a logical principle: a system with multiple independent arbitrators tends to inconsistency, while a system with a single defining source can enforce consistency. In philosophical terms, it hints at the law of non-contradiction – something cannot be true and false in the same respect at the same time. If you have numerous “truth-givers” (masters) issuing edicts, their edicts might contradict, violating the unity of truth and thus creating falsehood in at least some of those edicts. But a single source of truth, especially if conceived as an omniscient God, would not contradict Himselfthequran.love. The one master ensures a single coherent logos or logic governing the slave’s life. This can be extrapolated to the view that objective truth is singular; apparent plural “truths” that conflict cannot all be valid. As the Quran says elsewhere, “Allah has sent down the best discourse, a Book [with parts] resembling each other, consistent (mutashābihān)…” (39:23) – its verses reaffirm and resemble one another, never nullifying each otherthequran.love. In sum, Qur’an 39:27–29 uses practical imagery to convey an abstract but crucial point: truth, to be truth, must be one and self-consistent. Diversity of expression (parables of many kinds) does not imply diversity of truth – the Quran’s diverse teachings still spring from a single, unwavering source, just as a dozen rays of light can originate from one sun.

By ending the parable with “Praise be to Allah! But most of them do not know,” the Quran underscores gratitude for the guidance of unity, and sorrow that many people fail to appreciate this guidance. Historically, this could allude to those who persisted in polytheism or hypocrisy in the Prophet’s time, not realizing the blessing of the clear, unifying message being revealed. But it also speaks to all of us: humans often chase multiple ambitions, ideologies, or loyalties, thinking we can reconcile them, only to end up in spiritual and moral confusion. The Quran offers a gentle admonition that the way out of this confusion is to consciously embrace the One — one God, one ultimate truth. This does not mean life’s questions immediately become easy, but it means we acknowledge a single ultimate authority against which truth is measured, rather than being torn between competing versions of truth.

Finally, it is worth noting that the passage (39:27–29) begins with an invitation to reflection (“take heed”) and implicitly ends with the same – those who “do not know” are those who have not reflected enough on this parable. This bracketing with reflection connects directly to Qur’an 4:82, which also begins, “Will they not then reflect (yatadabbarūn) on the Quran?” The Quran is self-described as a book that demands our contemplation so that its coherence becomes manifestthequran.lovethequran.love. As we turn next to Qur’an 4:82 and the unity of knowledge, remember this image of the two slaves – it will serve as a touchstone for understanding why the Quran insists so strongly on its freedom from contradictions and why that matters for every sphere of human thought.

Qur’an 4:82 and the Unity of Truth in Revelation

“Then do they not reflect upon the Qur’an? If it had been from any other than Allah, they would have found within it much contradiction.” (Qur’an 4:82)thequran.love

Where Qur’an 39:29 uses metaphor, Qur’an 4:82 states the principle explicitly as a challenge and a proof. It invites doubters to scrutinize the Quran for inconsistencies, confidently asserting that any text not truly from the One God would inevitably reveal disparities and errors. This verse establishes internal consistency as a hallmark of divine revelation. As Allāmah Tabātabā’ī (a 20th-century exegete) noted, the Quran is here providing a falsification test for itself – essentially saying, “find a contradiction if you can,” on the premise that none will be foundthequran.lovethequran.love. The logic behind this is profound: truth is unified, so a scripture claiming to be “the Truth from the Lord of the worlds” must not fall prey to self-contradiction, nor contradict the reality that the same Lord createdthequran.love. If it did, it would undermine its claim to truth. As one commentary succinctly puts it, “truth from an All-Knowing source will not contradict itself, whereas a false or human-made scripture would inevitably contain discrepancies”thequran.love. In philosophical parlance, the Quran is appealing to the coherence theory of truth alongside the correspondence theory – it should cohere with itself and correspond with the real world, because God is the author of both the scripture and the cosmosthequran.love.

This criterion directly parallels the message of 39:29. The parable taught that multiple imperfect sources (gods or masters or ideas) lead to contradictions and strife. Verse 4:82 teaches that if the Quran had multiple authors or a non-divine source, it too would exhibit “much contradiction” – in its doctrines, its laws, its view of history or sciencethequran.lovethequran.love. The underlying assumption is that a merely human work, especially one revealed over 23 years on various topics, could not possibly maintain perfect consistency. Humans are forgetful, biased, and limited in knowledge; multiple human contributors would make this even more prone to discrepancy. By contrast, a revelation from a single, omniscient deity would, by its very nature, be consistent and self-affirming. One master, one message – many masters, jumbled messages.

Classical Islamic scholars gleefully expounded on this verse as evidence of the Quran’s miraculous nature. For instance, Imam al-Ṭabarī (d. 923) explains that skeptics plotting against the Prophet were challenged by 4:82 to examine the Book of Allah and realize “that what you (O Muhammad) have brought them is from their Lord” because of “the coherence of its meanings and the harmony of its rulings,” with each part of the Qur’an confirming the truth of other partsthequran.love. He goes on to say that if it were man-made, “its rulings would have differed and its meanings contradicted, and some of it would point out the corruption of other parts,” but “no such disharmony exists”, hence it must be entirely from Allahthequran.lovethequran.love. Al-Ṭabarī supports this by citing early authorities: Qatādah (d. 736) remarked, “Allah’s speech does not contradict itself; it is truth in which there is no falsehood. But people’s speech does contradict itself.”thequran.love. Another early commentator, Ibn Zayd, noted that the Qur’an “does not negate some parts with others, nor cancel out itself,” asserting that any perceived contradiction is due to “the deficiency of people’s understanding”, not a flaw in the textthequran.love. These insights encapsulate the classical view: God’s word is absolutely self-consistent, whereas anything tainted with human authorship will show seams and fissures.

To drive home the point, Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373) in his tafsīr writes: “Allah states that there are no inconsistencies, contradictions, conflicting statements or discrepancies in the Qur’an, because it is a revelation from the Most-Wise, Worthy of all praise. Had it been fraudulent and made up… they would surely have found therein contradictions in abundance. The fact that the Qur’an contains no such conflict is positive proof that ‘the Qur’an is the truth coming from the Truth – Allah.’”thequran.lovethequran.love. In other words, the Quran’s flawless internal harmony is “positive proof” of its divine origin for anyone who ponders it. Even orientalists who have scrutinized the Quran’s text are often struck by its consistency. The absence of contradictions holds despite the Qur’an addressing a wide array of topics (theology, law, ethics, history, cosmology) and doing so piecemeal over two decades. It is, as one modern researcher put it, “remarkably consistent in worldview and a cohesive moral and theological system, despite being revealed in response to varied circumstances”thequran.lovethequran.love.

The Quran doesn’t demand blind acceptance of this claim; it implores readers to “reflect (tafakkur) and contemplate (tadabbur)” on its verses to see the coherence for themselvesthequran.lovethequran.love. The verse 4:82 opens with “afalā yatadabbarūn al-Qur’ān” – will they not then deeply ponder the Qur’an? The use of tadabbur (deep reflection) rather than just “read” or “listen” is significantthequran.love. It suggests that any perceived contradictions usually come from a shallow reading or misunderstanding. Indeed, the Quran acknowledges that some of its verses are clear and fundamental and others are ambiguous or allegorical, as highlighted in Qur’an 3:7thequran.love. Those with perversity in their hearts might fixate on the ambiguous parts to create discord, but the faithful and knowledgeable say, “We believe in it; the whole (of it) is from our Lord.”thequran.love. This attitude mirrors the lesson of 4:82 – to approach the text seeking harmony, trusting that “the whole is from our Lord” and thus cannot conflict in reality. It also resonates with the Prophet’s teaching (as recorded by Ibn Kathīr) that “the Qur’an was not revealed to belie itself, but rather to confirm itself. So whatever you understand of it, act upon it, and whatever is unclear to you, refer it to those who have knowledge.”thequran.lovethequran.love. In essence, believers are instructed to interpret obscure verses in light of clear ones, never setting scripture against itself. Acting on Qur’an 4:82, therefore, involves both intellectual humility and rigor: humility in admitting that if something seems off, the flaw might be in our understanding, and rigor in working to resolve the difficulty through knowledge, context, and consultation, rather than declaring the text at fault.

Unity of Knowledge in All Spheres: Revelation and Reason in Harmony

The implications of Qur’an 4:82 extend well beyond scriptural study – they touch on the unity of all truth, whether revealed or discovered. The Quranic worldview does not separate “religious truth” from “scientific truth” or “historical truth” as fundamentally different species. Since Allah is One and the Source of all reality, any truth, in any sphere, ultimately comes from Him. Thus, genuine scientific findings, sound philosophical reasoning, and authentic theological principles cannot be in conflict in the long runthequran.lovethequran.love. This idea was famously captured by Pope John Paul II in 1996 when he affirmed, “Truth cannot contradict Truth,” referring to the harmony that must exist between the Word of God and the work of Godthequran.lovethequran.love. The Quran had voiced a similar principle ages earlier: it repeatedly calls us to observe nature, history, and our inner selves as “signs” (āyāt) of God, alongside the revealed āyāt of the Quranthequran.lovethequran.love. “We shall show them Our signs in the horizons and within themselves until it becomes clear to them that this [revelation] is the Truth,” Allah says in 41:53, indicating that the external world (horizons) and internal human experience both testify to the same Truth as the revelationthequran.love. In Qur’an 3:190–191, people of understanding are those who reflect on the creation of heavens and earth and conclude, “Our Lord, You have not created all this in vain!”thequran.love. The Quran pointedly asks, “Do they not look at the camels, how they were created… and at the sky, how it is raised?” (88:17–18) and then chides, “Will you not then reason (ta‘qilūn)?”thequran.love. The message is clear: empirical observation and rational analysis are meant to complement theological reflection, not oppose it. Both the Book of Nature and the Book of Scripture speak in unison if read correctlythequran.lovethequran.love.

How does this tie back to Qur’an 4:82 and 39:29? These verses establish a mindset that welcomes truth from any direction and seeks to integrate it. If the Quran is truly from God, it will not only be internally consistent but also externally consistent with realitythequran.love. Muslims historically took this as a cue to explore science and philosophy with confidence that doing so would strengthen their understanding of the Quran, not weaken itthequran.lovethequran.love. In medieval Islamic civilization, this gave rise to a culture of inquiry: mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and more flourished, driven by the idea (among others) that studying God’s creation was a form of worship and would vindicate the truth of the Quran. For example, when the Quran hinted at natural phenomena – such as the heavens and earth once being a joined entity before being split (Big Bang-like in 21:30) or the expansion of the universe (51:47) – later generations of Muslims saw in these verses a remarkable alignment with scientific discoveriesthequran.lovethequran.love. They argued that such congruence was possible only because the Author of the Quran and the Author of nature are one and the same, and “since both originate from the One Truth (Al-Ḥaqq), they must align.”thequran.love. If a conflict seems to appear, it is either due to a misunderstanding of scripture or a mistaken scientific theorythequran.love.

This integrative approach is essentially an extension of the one-master principle. Just as a believer should not follow two masters in the spiritual realm, we should not compartmentalize truth into watertight silos that contradict each other (for instance, accepting scientific evidence in daily life but rejecting it in religious matters, or vice versa)thequran.lovethequran.love. A holistic seeker of truth strives for coherence across disciplines – their theology does not negate empirical facts, their science does not dismiss profound spiritual realities. The unity of knowledge is a logical consequence of belief in the unity of God: all roads of genuine inquiry lead to the same summit. As the Quran puts it, “Allah’s signs in the heavens and earth, and in the soul, all point to the truth”, so any contradiction is a sign that we’ve misread one of the books. Indeed, Dr. Zia H. Shah proposes that the “Laws of Nature” can serve as a litmus test for certain interpretations of scripture – if a traditional understanding of a verse clashes with firmly established scientific truth, that understanding may need revision, “for ‘Truth cannot contradict Truth’.”thequran.love. This methodology, grounded in Qur’an 4:82, allows the Quranic understanding to evolve and ‘embellish’ over time as human knowledge increasesthequran.love, without ever abandoning the core belief that the Quran itself, rightly understood, is free of error.

An illustrative example is the scriptural mention of Prophet Noah’s long lifespan. The Bible outright asserts a 950-year lifespan for Noah, and a cursory reading of the Quran (29:14) says “he lived among his people a thousand years save fifty”. A literal interpretation here confronts biological reality – no human can live that long with our telomere limits. Rather than dismiss science or the verse, modern Muslim scholars use the non-contradiction principle to dig deeper. They propose that the Quranic phrasing likely refers to the era or influence of Noah’s mission (a figurative usage), not his biological agethequran.lovethequran.love. By doing so, they preserve the credibility of scripture and respect scientific truth, demonstrating that a coherent reconciliation is possible when one assumes at the outset that God’s word and God’s world do not conflict. This approach echoes the parable’s message on a broader scale: trying to serve “two masters” – one of blind literalism and one of empirical evidence – leads to a conflict, but serving the one Master of Truth leads to a resolution where scripture is understood in a way that accords with observed reality.

In philosophy, the Quran’s stand in 4:82 has been seen as an endorsement of basic rationality in faith. It essentially says logical consistency is a test of truth. The Quran even provides rational arguments within itself, as noted earlier with 21:22 (the argument for one God from the order in the universe)thequran.love. Muslim philosophers like Ibn Rushd (Averroes) and theologians like Imam al-Ghazālī, though often in different camps, both operated under the civilizational assumption that reason and revelation cannot truly contradict – if they seem to, you’ve misused reason or misunderstood revelation. This is why scholars like Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 1210) hailed 4:82 as “providing a logical proof of the Qur’an’s divine origin”, noting that no human, let alone an unlettered prophet, could author a text of such scope without tripping into contradictions over 23 yearsthequran.lovethequran.love. And if one believes that firmly, then one will also hold that no true scientific discovery will ever disprove a verse of the Quran, nor will any valid philosophical principle upend a Quranic teaching – rather, our understanding of the verse might need refinement or the scientific theory might change, but ultimately all knowledge should converge since it describes one reality governed by one Creator.

Thus, Qur’an 4:82 and 39:27–29 together advocate for a unified epistemology. On one hand, they reassure believers that their holy book will not mislead them with falsehoods or self-contradictions; on the other, they challenge believers to embrace all truth, from whatever the source, with the confidence that it can be integrated into their faith. Acting on these verses means cultivating a mindset that refuses to live a “bifurcated” life – accepting the laws of physics in the laboratory but suspending them in the house of worship, or using one standard of truth in religion and another in daily lifethequran.love. Such compartmentalization is, in a sense, serving multiple masters – it breeds an unspoken cognitive dissonance that can corrode one’s faith or intellect (or both). Many thoughtful individuals, when faced with a choice between religion and science presented as conflicting masters, have tragically felt forced to abandon one or the other. The Quran’s answer is: you need not abandon either, for there is only one Master of all knowledge. Truth is unitary. Find that unity, and you will find peace.

Psychological Dimension: Inner Conflict and Divine Consistency

The Quran’s emphasis on consistency is not an abstract doctrinal point alone; it touches on a deep psychological reality: human beings crave internal harmony and suffer when torn by contradictions. We have already seen how the parable of the masters (39:29) depicts the psychological turmoil of a person with divided loyalties or clashing directives. Modern psychology gives us language to further analyze this condition – notably the concept of cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance, first coined by Leon Festinger, refers to the mental discomfort experienced when one holds conflicting beliefs, values, or attitudes simultaneouslythequran.love. People in such a state feel pressure to resolve the inconsistency because it’s inherently uncomfortable to live with discord in the mind. They might change one of the beliefs, seek new information, or reinterpret the facts to restore a sense of consonancethequran.lovethequran.love. For example, if a person believes “honesty is the best policy” but routinely lies at work, this mismatch will likely bother them unless they justify or change one of those factors.

Now consider the scenario of faith: a person might believe in a religious doctrine but also observe things in the world that seem to contradict it. If they are taught they must simply accept the doctrine without question, they experience dissonance – their reason and their faith clash. If their religion provides no avenue to reconcile these, the person either suppresses their questioning (leading to an uneasy faith) or loses faith in the doctrine (sometimes leading to loss of belief altogether). Qur’an 4:82 is directly addressing this human psychological need by opening the door for questioning and resolution. It’s as if the Quran says: “Yes, scrutinize me. You will find I stand up to the test.” This encourages the believer to face apparent contradictions head-on, rather than live in denial or doubt. By promising that discrepancies are only apparent and urging reflection to solve them, the Quran alleviates the gnawing worry a reflective believer might have about their scripture’s integritythequran.lovethequran.love. In doing so, it prevents cognitive dissonance from taking root in the faithful’s heart – because the faithful is not asked to hold two incoherent ideas (e.g., that a perfect God revealed an imperfect book, or that religion demands rejecting evident truths of creation). Everything the believer is asked to accept is ultimately coherent and reasonable, even if understanding it fully requires effort. This Quranic approach stands in contrast to certain dogmatic approaches in history where questioning was discouraged, which often led to a build-up of suppressed doubts and eventual spiritual crises.

The double bind theory discussed earlier provides another angle. A person in a double bind (like a child with contradictory parents, or even a congregant hearing a sermon that conflicts with their lived reality) is put in a psychologically impossible positionthequran.lovethequran.love. Bateson’s research even linked chronic double-bind exposure to psychological disturbances like anxiety, depression, and in extreme cases hypothesized links to schizophreniathequran.love. Whether or not that extreme is true, it is intuitive that constant contradictions can “fracture one’s mental well-being.”thequran.love The Quran’s self-description as “without crookedness” and its exhortation to avoid contradictions can be seen as a Divine mercy to shield humanity from this fracturing. By giving consistent guidance, the Quran acts as a kind of cognitive anchor. A believer who genuinely follows the Quranic paradigm will strive to align their beliefs and actions in a consistent manner, reducing inner conflicts. When challenging situations arise (moral dilemmas, new information, etc.), the Quran encourages them to return to reflection and knowledge to resolve the issue, rather than live with a painful split in their mind or heartthequran.lovethequran.love.

On a communal level, a contradiction-free scripture fosters psychological safety among its community. If the community firmly believes “this book has no errors or conflicts,” then differences in understanding can be debated with the shared assumption that truth is somewhere in the reconciliation, not that one verse might invalidate another. This reduces the kind of factionalism that arises when people take irreconcilable positions. It’s noteworthy that Ibn Kathīr mentions a hadith where the Prophet Muhammad rebukes companions who were arguing loudly over an interpretation: “The nations before you were destroyed by their disagreements… The Qur’an was not revealed to contradict itself… So whatever you understand of it, act upon it, and whatever is unclear, refer to those who know.”thequran.lovethequran.love. This is psychological wisdom: it nips in the bud the ego-driven quarrels that can come from religious debate, by re-centering everyone on the notion that the Qur’an is self-confirming, not self-cancelling. The companions’ raising of voices might indicate anger or anxiety – precisely the emotions that flare when people fear that if their interpretation is wrong, the whole truth might collapse. The Prophetic counsel eased their anxiety: the Quran isn’t pitting verses against each other, nor should you. This creates a more stable, calm approach to learning and discussing the religion.

For individuals, acting on verses 39:29 and 4:82 means actively seeking a unified self. It means not living a double life where religious persona and everyday persona are at odds, nor clinging to beliefs that one secretly feels are illogical or untrue. The Quran invites you to ask, ponder, resolve. The end result is a person whose beliefs, reasoning, and emotions can align – the head and the heart at peace. Psychologically, this is akin to achieving what Carl Rogers called congruence, where a person’s self-image and experience line up, or what Abraham Maslow hinted at in self-actualization, where one is deeply truthful with oneself and reality. A believer convinced of the unity of truth will avoid self-deception. If a scientific fact challenges their current understanding of scripture, instead of living in denial (which causes subconscious stress), they will either adjust their understanding of scripture (if possible within legitimate interpretation) or wait patiently for more clarity, trusting that there is an answer even if they don’t see it yetthequran.lovethequran.love. This trust is not blind faith; it’s faith in the principle that reality is coherent – a principle that even many non-religious thinkers uphold in their own fields (science assumes nature is coherent and not ultimately paradoxical). In a believer’s life, this translates to an inner tranquillity. There is a beautiful term in the Quran and Hadith: sakīnah, a peace or calm that “descends upon the hearts” of believers. One aspect of sakīnah is surely this peace of consistency – the restfulness of not being pulled apart inside.

In contrast, consider those who either don’t reflect or who serve “many masters” in life. They might constantly feel unease – perhaps without even identifying it – because different commitments tug at them in different directions. A modern example: someone might feel torn between materialist values (e.g. “success is making the most money”) and spiritual values (“success is being righteous”), between individualist impulses (“I should do what’s best for me”) and collective ones (“I should sacrifice for family and community”). While life will always have some competing values to balance, a worldview that provides a hierarchy and harmony of values spares a person intense confusion. The Quran’s monotheism and consistency give exactly that: by recognizing one ultimate Master, all other concerns can be ordered beneath that Master’s guidance. The money, the family, the self – all have rights and roles defined in a non-contradictory way by God’s unified law, so one need not sell one’s soul to satisfy one aspect of life at the cost of another. The psychological benefit is immense: it “liberates us from contradictory impulses and ideas, guiding us toward coherent living.”thequran.love.

In summary, the psychological commentary on these verses reveals that faith is not supposed to be a source of cognitive dissonance or mental strife. If it is, something is wrong – either one’s understanding of the faith or the faith being followed. The Quran boldly claims that its path will relieve the thinking person’s inner conflicts, not exacerbate them. “Will they not then ponder?” is both a challenge and an assurance – ponder, and you will see the pieces fit; neglect reflection, and you might wrongly imagine contradictions that disturb youthequran.lovethequran.love. And as 39:29 teaches by analogy, unifying one’s devotion leads to “inner consistency and tranquility,” whereas fragmentation leads to “chaos within.”thequran.love Psychologically, then, the Quran positions itself as a cure for the anxieties of a divided mind. Little wonder that many who experience a crisis of meaning or identity find solace in rediscovering their faith not as a set of disjointed rules, but as a coherent narrative and purpose that ties together the loose strands of life.

Philosophical Dimension: Rational Coherence and the Principle of Non-Contradiction

Philosophy, at its core, prizes logical consistency. One of the oldest and most inviolable laws of classical logic is the Law of Non-Contradiction: A proposition and its negation cannot both be true at the same time and in the same sense. In other words, truth cannot undermine itself. Remarkably, Qur’an 4:82 can be seen as an application of this logical axiom to the realm of religious epistemology: if a scripture were both claiming to be from God and yet contained assertions that clash with one another (or with reality), it would violate the law of non-contradiction and thus prove itself falsethequran.love. By contrast, a scripture that is entirely self-consistent upholds this law, and if one also finds it consistent with external truths, it gains credence as true. The Quran is effectively saying: we invite you to test us with the principle of non-contradiction. It’s a philosophically robust criterion – much more concrete than a subjective spiritual experience or an authoritarian demand for belief. It shifts the debate into rational terms all humans can engage with. As one modern writer noted, Qur’an 4:82 “resonates with the classical logical axiom that truth cannot be self-contradictory.”thequran.love.

The parable in 39:29 also has a philosophical implication: it suggests a unity behind the multiplicity. The scenario of many masters versus one master can be extrapolated to the metaphysical idea that behind the multiplicity of phenomena in the universe, there is a single unifying agency or principle (One God), which is why the universe operates coherently. Conversely, if the universe had no single unifying principle (many unrelated masters/gods or blind forces at odds), we would expect incoherence and chaos. Philosophically, this touches on arguments in the vein of the cosmological argument and teleological argument for God’s existence – the cosmos exhibits order and unity, which implies a singular creative will or lawgiver, as opposed to competing wills. The Quran’s argument in 21:22 (no multiple gods, or creation would collapse) is a brief statement of the argument from design consistencythequran.love. The parable in 39:29 brings that lofty concept to the personal level: your life, your moral universe, also needs a single organizing truth. A life philosophy that tries to treat disparate, contradictory goals as all “true” will lead to failure of the system of thought, just as a worldview that accepts contradictory premises will collapse logically. In modern terms, the Quran here advocates for a coherentist epistemology within a monotheistic framework: all truths must cohere with each other, and they do so under the umbrella of the Ultimate Truth (Allah).

Critically, Qur’an 4:82 not only aligns with the law of non-contradiction but also introduces what philosophers of science call a falsifiability test. The verse essentially says: if you find a single significant contradiction in the Quran, you can disprove its divine claim. This is akin to saying a single black swan can disprove the theory that “all swans are white.” By putting its credibility on the line, the Quran establishes a kind of contract with the rational reader: it doesn’t fear examination. This is philosophically intriguing because it moves the basis of belief from pure subjective faith to an objective criterion. It implies that faith in the Quran can be, in part, evidence-based – evidenced by the Quran’s enduring consistency despite every opportunity for inconsistency to creep in (lengthy revelation period, varied content, etc.). The philosopher of science Karl Popper argued that a hallmark of a scientific theory is that it should state what would count as a falsification, even if that falsification never occurs. The Quran did something analogous: “find a contradiction” is the falsification condition. As of 1400+ years later, Muslims maintain that no one has proven any real contradiction in the text (apparent contradictions having scholarly resolutions). This claim forms part of what Muslims call the I‘jāz (inimitability or miraculous nature) of the Quran – usually discussed in terms of linguistic excellence, but also including its consistency and accurate knowledge. In an academic sense, whether one accepts the Quran’s divinity or not, one must reckon with the reality that it is extraordinarily self-consistent for a text of its length and historical context. This invites a philosophical question: how did that consistency arise? The Quran’s own answer is that it could only be because it is from an All-Knowing, Single Source rather than piecemeal human sourcesthequran.lovethequran.love.

Another philosophical dimension here is the interplay of reason and revelation. By validating non-contradiction, the Quran is endorsing human reason (ʿaql) as a means to engage with revelation. It is telling the reader that their rational faculties are not only useful but necessary in appreciating the Quran’s truth. One must reflect, contemplate, think – these are rational activitiesthequran.lovethequran.love. Thus, the Quran positions itself not as an anti-rational mystic text, but as a reasonable revelation that welcomes critical thought. Historically, this gave confidence to Muslim philosophers and scientists that their use of reason was not an affront to God but a way to understand God’s work. The only proviso was that reason itself must operate within its proper bounds and methods – but that’s true of any field. The very idea of Islamic theology (ʿilm al-kalām) and jurisprudence (fiqh) using systematic logic and Greek-influenced reasoning owes much to this Quranic encouragement to critically examine and reconcile. The Mutazilites (a rationalist Islamic school) famously held up non-contradiction as almost a theological principle, arguing that God’s justice means He would not deceive us with contradictions. Even the more scripturally conservative scholars, while wary of unfettered speculative reasoning, still assumed the Quran to be fully coherent and used reason to interpret it (e.g., principles of abrogation or context to resolve apparent tensions).

Now, looking at unity of knowledge philosophically: The Quran fosters a kind of monism of truth. In philosophy of science today, there is debate about whether we live in a ultimately coherent universe or a “multiverse” of disconnected truths. The Quran comes down firmly on the side that all truths are part of Truth, and thus there is an underlying unity. This has significant implications. For one, it means that the search for knowledge is a sacred task – every truth discovered is a fragment of the divine tapestry. For another, it implies that contradictions between established truths are illusory or temporary. This underlies the Islamic Golden Age attitude where scholars like Ibn Sina could be at once physicians, philosophers, and theologians – they didn’t compartmentalize knowledge, because they believed in its unity. Contrast this with a post-modern relativistic view that each narrative has its own truth and they can all contradict each other without issue. The Quranic stance is more akin to the classical philosophical notion that truth is objective and one, even if perspectives differ.

Finally, consider the ethical philosophical dimension: Consistency is not just an epistemic value, but an ethical one. Integrity, for example, is often defined as consistency between one’s principles and actions. Hypocrisy is the opposite – a form of contradiction between what one professes and what one does. Interestingly, the Quran frequently condemns hypocrisy (nifāq) in harsh terms, and one could say hypocrisy is living a lie, a contradiction. A hypocrite is essentially a person with two “masters” – the master of public image piety and the master of private desire – and those conflict. The Quran says the hypocrite is in a state of disequilibrium, “wavering between (believers and disbelievers), belonging neither to these nor those” (4:143). This is a moral psychological contradiction. True faith, by contrast, should harmonize inner and outer, belief and practice. Thus, the Quran’s emphasis on a contradiction-free scripture is mirrored in its desire for the believers to be contradiction-free in character. Theologically, that means aligning one’s will with God’s will (Islam’s very meaning: submission to the One). Philosophically, it means living according to a coherent value system. Serving one Master (God) philosophically translates to having a singular moral telos (end goal) that orders all lesser goals, rather than being a value pluralist in the sense of clashing ultimate ends.

In summary, from a philosophical angle Qur’an 39:27–29 and 4:82 affirm that reality has an underlying logical unity bestowed by the One, and that our beliefs should mirror that unity. They assert that faith and reason are allies in discovering truth, since any authentic conflict between them would indicate a flaw in one side or the other, not a flaw in truth itselfthequran.lovethequran.love. The call to reflection is a call to do philosophy – to question, to analyze, to synthesize. The assurance of no contradiction is an assurance that this endeavor won’t ultimately be in vain; there is a consistent answer to be found. And monotheism is presented as the key to metaphysical coherence, solving what one might call the “problem of the one and the many” by asserting that the One underlies the many. It’s a comprehensive approach that integrates logic with spirituality – something arguably unique among religious scriptures to state so explicitly. Little wonder the Quran has been termed a “Manifesto of Reason” by some scholars of religion. It is inviting the philosopher (in the broad sense of any lover of wisdom) to engage with it deeply, promising that the deeper one goes, the more the apparent jigsaw of life’s questions will start to form a clear picture – a picture of truth that is consistent within and without.

Theological Dimension: Divine Consistency, Monotheism, and Interfaith Implications

Theologically, the verses in question reinforce core Islamic doctrines while also offering a basis for dialogue with other faiths. The primary theological takeaway is the confirmation of tawḥīd (absolute monotheism) not just as a numerical statement (that there is only one God), but as a qualitative statement: God’s oneness ensures the coherence of His message. In Islam, God is not only One in being, but also consistent in will and word. The Quran contrasts this with other theological systems by implication. For example, the doctrine of the Trinity in Christianity posits one God in three persons – a mystery that some argue leads to paradoxes (how can 3 = 1?). The article “Truth Cannot Contradict Truth” notes that when the Pope applied rational scrutiny to faith, if done fully “it acts as a universal solvent, dissolving those doctrines that cannot withstand the scrutiny of reason and evidence… when applied to the Trinity… these doctrines dissolve, leaving behind the pure, insoluble gold of Monotheism.”thequran.love. This reflects an Islamic perspective: any theological concept of God that violates basic logical unity is seen as a human-added contradiction. The Quran (4:171) addresses Christians: “do not say ‘Three’ – intahu (stop it), it is better for you; God is only one God.” The parabolic way of saying that is 39:29’s image – multiple masters versus one. The masters “disputing with one another” could be likened, polemically, to the wrangling of differing theologies; whereas one Master suggests the elegant simplicity of pure monotheism.

Islamic theology asserts that God’s nature and God’s messages are perfectly self-consistent. Unlike in some mythologies or even Biblical narratives where God “regrets” or changes His mind or issues covenants that later get superseded in unpredictable ways, the Quran insists God’s plan is coherent (even if revealed gradually) and His attributes do not conflict. God is Most Merciful and Most Just simultaneously, and Islamic theology has long wrestled with balancing those without contradiction (e.g., through the concept of a designated Day of Judgment where justice is fulfilled, reconciling mercy and justice across time). The idea of divine consistency also provides comfort: believers trust that God won’t “trick” or confuse them. He won’t send prophets with clashing messages or change the requirements of salvation arbitrarily. This is one reason Muslims believe Muhammad ﷺ came not to start a new religion but to confirm and clarify the perennial truth sent to prior prophets (Qur’an 3:3-4) – because truth is one, previous revelations in their original form were aligned with the Quran, and only distortions caused perceived differences. When 4:82 says “if it was from other than Allah, you’d find much contradiction,” it hints not only at internal textual consistency but at consistency with previous revelation. God’s authorship guarantees a fundamental unity among all true revelations. It’s human interpolations that cause contradictions between scriptures, from the Islamic viewpoint.

This leads to an inclusive theological outlook: the Quran invites People of the Book (Jews and Christians) to a common word: to worship none but God (Qur’an 3:64). Implicit is the appeal to drop elements not consonant with pure monotheism (like attributing divinity to Jesus or other beings), because those are seen as contradictions that crept in. The logic is much like 4:82 – if doctrines conflict with the core message of God’s oneness or with clear reason, they likely stem from “other than Allah” (i.e., human hands) and should be discardedthequran.love. This principle of eliminating theological contradictions has been a driving force in Islamic reform movements and also in its interface with other faiths. For example, when engaging with Christianity, Muslim scholars often highlight the incoherence of certain tenets (like the Incarnation or Original Sin in light of evolution) to argue that those cannot be true since truth is coherentthequran.lovethequran.love. They then present Islam’s view as one that retains both spiritual depth and rational clarity – in line with the Quran’s ethos of divine consistency. This isn’t done merely to win arguments, but to uphold the idea that God’s message is universal and free of internal dispute, so any serious seeker of God should gravitate toward the belief system with the fewest internal and external contradictions. Indeed, the Quran uses a term millah Ibrāhīm ḥanīfā – the pure monotheistic creed of Abraham – implying that at its root, true religion has always been one and the same, free from the crookedness of polytheism or man-made dogmas.

Another theological aspect is the Quran’s guidance on handling apparent contradictions or ambiguities in scripture. The Islamic scholarly tradition developed tools like tafsīr (exegesis), uṣūl al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence), and sciences like nasikh wa mansukh (abrogation theory) to reconcile verses. This was driven by the conviction that there must be a reconciliation. As referenced above, scholars explained, for instance, that abrogation (naskh) is not a real contradiction but a shift in legislation for a different time – the Quran addresses it within itself (Qur’an 2:106) and it fits the idea of a planned progression rather than an accidental inconsistencythequran.lovethequran.love. By systematically studying context (asbāb al-nuzūl), language, and juristic hierarchy of verses, they maintained a cohesive understanding. This contrasts with, say, certain Biblical interpretations where contradictions are sometimes just acknowledged and left (or attributed to different human sources like “the Yahwist source vs Priestly source” etc., which from an Islamic view is precisely evidence of multiple human hands). The Muslim approach rooted in 4:82 has generally been: if two passages seem to conflict, dig deeper – perhaps one is general and one is specific, or one came later to refine the other, or we have mistranslated something. There is always a resolution because God wouldn’t give conflicting commands with no clarification (that would be like the double-binding parent, which we know is not how God operates). This has kept Islamic theology and law in a constant process of refinement to ensure coherence. While detractors might see some of this as “harmonizing at all costs,” for believers it is a necessary and virtuous intellectual labor mandated by the Quran itselfthequran.lovethequran.love.

One might ask, does the Quran contain any sort of contradiction or tension? Believers say no, but skeptics have posed challenges (on issues like inheritance laws in different verses, or the timing of creation in days, etc.). Without diving into each, it’s noteworthy that Muslims have answers to these, often involving nuanced readings of the Arabic or context. This in itself shows the theological stance: there are answers; we just have to find them. It’s a sharp contrast to a relativistic acceptance of “well, different parts say different things, so what?” The Quranic stance is never to say “just accept the contradiction as mystery” – it says if you think it’s a contradiction, you haven’t thought enough or sought enough knowledge. This fosters a theology that is quite dynamic and engaging. It propelled great minds like Imam al-Ghazālī to rigorously examine theology and philosophy to resolve perceived conflicts (his famous work Tahāfut al-Falāsifah was about resolving what he saw as philosophers’ contradictions to revelation). It also influenced the likes of Shah Waliullah in the 18th century to reconcile Sufi metaphysics with Shariah, and more recently modernists to reconcile Islam with modern science – all under the umbrella that since truth is one, these endeavors should succeed to the extent both sides are truly understood.

From an interfaith perspective, verses 39:29 and 4:82 offer a potential common ground as well as a gentle challenge. The common ground: all Abrahamic faiths (and even many non-Abrahamic) agree that God is truthful and not the author of confusion. A devout Jew or Christian would agree in principle that God’s word shouldn’t contain real contradictions (they might dispute the application, but not the principle). So when Muslims highlight this verse, it often piques interest: “Our scripture openly invites this test of consistency – does yours?” It can lead to constructive comparison. For instance, biblical inerrantists claim the Bible has no real contradictions; Muslims then discuss examples where that might not hold (like differing genealogies or historical accounts), not merely to score points but to suggest: perhaps those issues indicate where the Bible was altered by humans, whereas the Quran was preserved from such tampering, fulfilling 4:82’s claimthequran.lovethequran.love. Meanwhile, those of other faiths might appreciate the Muslim commitment to rational integrity in scripture, even if they interpret their own texts differently. The bridge-building happens when all agree that God’s truth is consistent – from there, they can jointly explore which theology upholds that best. It’s notable that some modern Christian theologians, grappling with science, have echoed Quranic-like reasoning. The Pope’s quote we mentioned, “If a contradiction appears to exist, it is a result of human error — either a misinterpretation of scripture or of scientific data,”thequran.love could almost have been taken from a Muslim scholar’s pen (indeed, many Muslim writers eagerly cite it). This shows that the principle is transcendent: a thoughtful Christian or Jew or Hindu would also try to resolve contradictions in their understanding of God’s message and the world.

One practical section requested was how acting on these verses builds a bridge between atheism and theism, and among different religions. Let’s address that explicitly here, as it sits at the intersection of theology and outreach:

- Atheism and Theism: One of atheism’s strongest critiques of religion is that religions are internally inconsistent or contradict established facts – for example, claiming miracles that violate natural laws, or holding doctrines that seem logically impossible. By stressing that Islam’s scripture is free of contradiction and aligning faith with reason, Muslims can appeal to atheists on a common ground of rationality. Many former atheists who became theists (and specifically Muslims) often cite that Islam’s concept of God and scripture “made sense” logically, whereas they couldn’t reconcile faith with reason in other contexts. Acting on 4:82 means Muslims should always be willing to discuss evidence and logic with atheists, rather than retreating to “just have faith.” This can earn the respect of atheists. In fact, the Quran often addresses doubters with reasoned arguments (e.g. the creation of life, the fine-tuning of the universe, the purposefulness in nature), suggesting that it expects skeptics to be won over not by force or blind preaching, but by evidence of consistency and truth. An atheist might start from “there is no God” because they see contradictions in religious narratives; a Muslim can respond by demonstrating a lack of contradiction in the Quranic narrative, or by showing how Islam tackles contradictions that atheists also dislike (for instance, the conflict between science and a literalist reading of Genesis – Islam avoids that by offering interpretations of creation that accommodate scientific findings)thequran.lovethequran.love. Moreover, the very idea that a holy book would invite falsification is intriguing to a scientific mind – it’s something to test. Many a skeptic has taken that challenge (to find errors in the Quran) and along the way become impressed by the scripture’s depth and consistency, sometimes leading to conversion. In that sense, 4:82 is a bridge because it encourages a method of engagement (scrutinizing the text) that both the skeptic and believer can agree on as fair. There’s no appeal to “shut your mind and just believe”; it’s quite the oppositethequran.lovethequran.love. This shared rational ground can transform adversarial debate into a cooperative search for truth.

- Among Religions: Acting on these verses within Islam fosters a humility and openness in interfaith dialogue. If a Muslim believes truth is one and cannot contradict, they will also believe that any true elements in other religions must ultimately be compatible with Islam’s truth, and any contradictions are either misunderstandings or accretions. This leads to a kind of inclusivism: Islam is seen not as a totally new truth but as the pure form of the one truth that has been partially present elsewhere. A Muslim can thus appreciate, for example, the monotheistic core of Judaism or the ethical teachings of Christianity or the spiritual insights of other traditions, saying these align with Islam (the one master’s voice echoing) and use the contradictions (perhaps polytheism in folk Hinduism, or Trinitarian complexity in Christianity, etc.) as points to gently invite others to reconsider those aspects in favor of a simpler unity. It’s noteworthy that the verse 39:29 doesn’t vilify the slave with many masters; it pities him for the confusion. Likewise, Muslims acting on these teachings shouldn’t scorn others for having contradictory beliefs, but empathize that it’s a difficult position, and then offer the ease of unity. The Quran says, “Allah intends for you ease, and does not intend for you hardship” (2:185) – in context about legal rules, but broadly true of faith. The ease of a coherent faith is a gift Muslims can share. For example, when engaging with Christians, rather than only pointing out biblical inconsistencies, a Muslim can also highlight that Islam believes in Jesus and Moses but within a consistent theology that avoids the puzzles of incarnation or atonement theories. This potentially appeals to Christians’ own desire for clarity. In dialogues with Hindus or Buddhists, one can find common values and then show how Islam keeps those values without internal conflicts (like strong family ethics without the contradictions of caste, or a reverence for the transcendent without falling into idol worship).

By building bridges on consistency, we also build mutual respect. A Muslim firm in these verses will respect that a true contradiction is a deal-breaker, so they will not ask someone of another faith to accept something that violates their reason. Instead, they’ll articulate Islam in a way that meets the rational and spiritual needs of the other. This approach can transform inter-religious engagement from trying to win a debate to inviting to shared principles. For instance, Pope John Paul II’s maxim “truth cannot contradict truth”thequran.love is a Catholic expression that Muslims wholeheartedly agree with. A Muslim can use that as a starting point: “Your Pope said this, and we agree; let’s examine various doctrines under that light.” This is a respectful way to dialogue, using the others’ esteem for reason and their own sources. In the cited article inviting Catholics, Dr. Zia Shah writes that Islam offers the “Rational Sanctuary” the modern believer seeks – “a faith where the ‘Book of Nature’ and the ‘Book of Scripture’ speak the same language.”thequran.love Such language is inviting, not confrontational, and it addresses a common concern (the rift between science and religion). It builds a bridge by saying: we both value rational integrity, so let’s explore Islam which claims to fulfill that.

In sum, the theological dimension of these verses reinforces Islam’s identity as a religion of pure monotheism and truth and provides a platform for reaching out to others. It asserts that any deviation from singular divine truth – be it polytheism, unwarranted dogma, or philosophical error – will produce conflicts that trouble the heart and mind. The cure is to come back to oneness: one God, one truth, one humanity under God. The Quran famously says in 2:256 “let there be no compulsion in religion; truth stands out clear from error.” The idea of truth’s clarity links to the idea of consistency: error often reveals itself by inconsistency. Therefore, Muslims trust that by patiently clarifying and comparing, the truth of Islam will shine without coercion. It’s an inherently dialogical theology – it assumes a shared rational ground with the other, and thus encourages bridge-building through clarity.

We have thus seen how these Quranic verses weave together a tapestry where psychology, philosophy, and theology all point to a single insight: embracing the One Truth of God yields coherence and peace, whereas following many unfounded ideas yields contradiction and strife in both mind and society. Now, let us conclude with a thematic epilogue that reflects on how living in accordance with this insight can lead humanity toward a more harmonious understanding of existence.

Epilogue: Toward a Coherent Understanding of Reality

The Quranic vision articulated in 39:27–29 and 4:82 is ultimately a call to wholeness – a wholeness of faith, reason, self, and society under the guidance of the One. It teaches that consistency is the fingerprint of truth, and thus invites us to seek consistency in our scriptures, in our worldview, and in our very souls. The imagery of a person trying to serve many quarrelling masters versus one benevolent master is not just a theological parable; it is a mirror held up to our lives. In that mirror we may see our own fragmented pursuits and contradictions – and we are gently urged to reconcile them by latching onto the singular rope of divine truth that the Quran provides. As one commentary eloquently summarized, “God’s Word is presented as a perfectly coherent guidance for humanity.”thequran.lovethequran.love In practice, this means the more we align with that guidance, the more integrated and less conflicted our lives become.

The journey to coherence begins with reflection (tadabbur). The Quran repeatedly asks, “Will you not then ponder?” – suggesting that sincere contemplation is the key to unlocking its consistencythequran.lovethequran.love. If something perplexes us, we do not abandon either the Book or our God-given intellect, but use one to illuminate the other. This is how “locks upon the hearts” are removed (as 47:24 hints)thequran.lovethequran.love. An image comes to mind from our sources: a solitary figure standing under a starry sky, deep in thought. Such an individual symbolizes the melding of wonder and reason, gazing at the vast, orderly cosmos while recalling the Quran’s verses, until the realization dawns that it is all one reality. There is no forked truth – every genuine insight from nature, every correct use of logic, every authentic spiritual experience converges. In the words of the Quran, “Allah has sent down the best statement: a consistent Book wherein is reiteration” – its messages echo through nature, history, and the chambers of the heartthequran.love. When we attune ourselves to that consistency, we begin to see pattern instead of puzzle, design instead of disorder. The world itself starts to feel like a scripture – ayāt (signs) everywhere – and the scripture begins to live in the world.

Acting on the guidance of these verses also means striving for integrity in the moral realm. Just as the Quran does not contradict itself, a true believer should not live in contradiction with themselves. The Quranic ideal is a person “unified through one Master,” whose actions faithfully reflect their beliefs and whose private life mirrors their public claimsthequran.lovethequran.love. This integrity builds trust and understanding across communities. Imagine a world where adherents of every religion were committed to eliminating contradictions in their own texts and traditions – it would force all to purge interpolations, rethink irrational dogmas, and abandon extremist misinterpretations. The result would be convergence: perhaps different paths finding common ground in the one mountaintop of truth. In this sense, verses like 4:82 are not just about the Quran, but about a principle that can heal religious divides: No true revelation will negate another; all true revelations, like rays of one sun, will point consistently to the One Light. If contradictions seem to occur, let collective reflection and humility resolve them – for “people’s words are what differ; God’s word is truth, not to be doubted”thequran.lovethequran.love.

Ultimately, the Quran sets forth a challenge soaked in hope: find a flaw if you can, and if you cannot, then come join this chorus of truth. It doesn’t fear the seekers of truth – it embraces them, assuring that any who come with open minds will find “no crookedness” thereinthequran.lovethequran.love. This is a remarkable stance that turns every honest questioner into a potential ally. A famous saying attributed to ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib encapsulates a related wisdom: “The Quran is like a rope which the more you pull, the more it extends – it never disappoints those who explore its depths.” In the same way, the deeper one inquires into science, philosophy, or any branch of knowledge, the more the unity of Allah’s creation reveals itself, never disappointing the one who believed that faith and reason would meet. Indeed, “truth cannot contradict truth” – when lived fully, this becomes not just a theological maxim but a lived reality of serenity. The believer then walks through life with an enlightened mind and an undivided heart, experiencing what the Quran calls sakīnah (tranquility). It is the tranquility of knowing that one’s worldview has “no doubt” and “no contradiction”thequran.lovethequran.love, a coherent, “homogeneous and integrated” understanding of the Qur’an and by extension the worldthequran.love.

In closing, the commentary on Qur’an 39:27–29 and related verses affirms that the Glorious Quran offers a path “beyond doubt and without contradiction.” It challenges us to overcome our inner conflicts and societal schisms by embracing divine consistencythequran.lovethequran.love. Acting on this means continuously bridging gaps – between our desires and our duties, our knowledge and our faith, our community and others. It means building bridges of dialogue between religions on the premise that we are all searching for the coherent truth of one Almighty. And for the individual, it means building a bridge between the mind and the heart – so that what we hold true in concept translates into what we feel and do, without friction. When a person, a community, or a civilization reaches this state, they exemplify what the Quran envisioned: a harmonious whole, reflecting the harmony of God’s singular truth. This is not a utopian dream but a promise – a promise that when we align with the One, we become one (in ourselves and with each other). Thus, the path of “unity through one Master” is the path toward a healed psyche, a rational religion, and a peaceful worldthequran.love. In a fragmented age, this Quranic wisdom beckons like a light at the end of a tunnel, assuring us that all the diverse threads of human inquiry and experience can indeed weave into a seamless tapestry of meaning – if we are willing to follow the thread of Consistency that originates from the Divine.

Praise be to Allah, the One, for He has sent down a guidance with no crookedness – a guidance that unites what was scattered and clarifies what was confused.

وَالْحَمْدُ لِلّٰهِ رَبِّ الْعَالَمِينَ – “Praise belongs to God, Lord of all the worlds.”thequran.love

If you would rather read in Microsoft Word file:

Leave a comment